Photo: Carl Schultz

ct.jpg)

interview

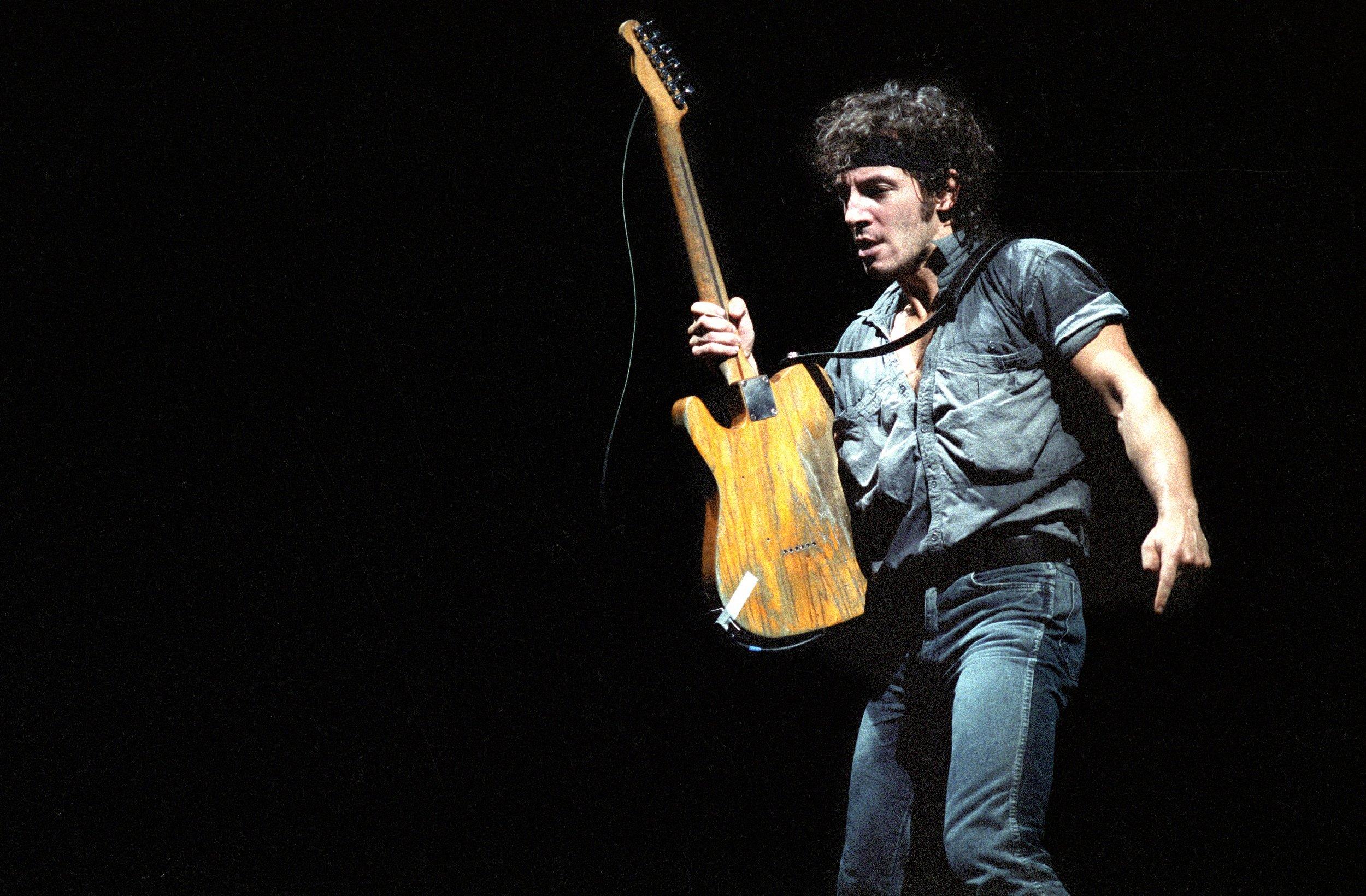

Living Legends: Nils Lofgren On His Guitar Philosophy, Staying Sober & Meshing With Iconoclasts Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music who are still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com sat down with Nils Lofgren, an inspired solo artist and key collaborator of Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Living Legends is an editorial series that honors icons in music and celebrates their inimitable legacies and ongoing impact on culture. In the third edition, GRAMMY.com caught up with Nils Lofgren, a revered solo artist and crucial accompanist to Neil Young in Crazy Horse and Bruce Springsteen in the E Street Band.

Neil Young and Crazy Horse may have been in rustic, cozy climes while recording their latest album, Barn, but departed friends were heavy on their minds. From decades-long manager Elliot Roberts to luminous vocalist Nicolette Larson and beloved pedal steel guitarist Ben Keith, Young's cosmology is populated with far too many lost colleagues. One of the cruelest losses was Danny Whitten, the Horse's brilliant first guitarist who succumbed to an overdose far too young.

Current guitarist Nils Lofgren is keenly aware he could have ended up like him.

"If you're struggling with issues like that, you only have three choices: You get cleaned up, you get locked up or you get covered up," the guitarist, accordionist and Horseman — who's played with Young for more than 50 years and been sober for almost 35 — tells GRAMMY.com. He cites fellow survivors Ringo Starr and Joe Walsh, who both wrested themselves from addiction, and remain healthy and creative in their 70s and 80s.

Of course, Lofgren is known for far more than cleaning up his act; he's one of the most evocative, graceful guitarists on the planet, and an inspired accompanist in the Horse and Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band. But as per his blunt axiom, living clean has allowed him to flourish as an artist and human being. He speaks with palpable gratitude and humility, both crucial weapons for breaking vicious cycles. And the best part is: he's got more music in him.

With Barn and a new solo, live album, Weathered, out in the world, GRAMMY.com presents an exclusive interview with the guitar extraordinaire about his past, present and future. (The conversation occurred before Lofgren removed his music from Spotify in lockstep with Young over COVID misinformation.)

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Barn film made the sessions seem like a marked difference from the experience of making Colorado. While that experience was a little more exotic — you were at a 9,000-foot elevation — recording in the barn seemed much more comfortable.

"Comfortable" is a good word. Gosh, we all go back well over half a century together — as friends and fellow bandmates and musicians.

Being in the middle of a pandemic and having everybody vaccinated and testing and safe, you knew you were in a safe environment. Which, in and of itself, was kind of an out-of-body experience at the height of COVID, when you were worried sick at home and spraying mail down. Of course, that was from pre-vaccination.

It was pretty extraordinary. The initial intent was just to see each other and be musicians for a week or so. Neil thought he might have four songs — maybe five — but he kept writing and had more material.

We were sitting around, telling stories and just being grateful to be with each other — to go play for hours at a time and work on new music. It was an extraordinary 12 or 13 days — whatever it was. My wife Amy always says if I'm going to miss my birthday at home, she couldn't find a finer place or circumstance.

You've seen Neil's career from the very beginning to the most recent part. What does it feel like to come back to Crazy Horse with 50 years of experience?

It's an extraordinary level of comfort, gratitude and familiarity. We call it the Gold Rush upright — the same piano I played when I was 18, when I played "Southern Man," "Only Love Can Break Your Heart" and "Don't Let It Bring You Down." To sing on that at 70 — 52 years later — and be with people you've been through so much with, in the studio and on the road, just hanging out, in endless rehearsals over the years [is remarkable].

I did the first Crazy Horse album while Danny was alive, with Billy [Talbot], Ralph [Molina] and Jack Nitzsche. That history just brings a beautiful comfort level. We had cameras rolling in a drafty old barn — Neil set it up like a nightclub, so there's a stage looking out. We never put on a set of headphones once. It's the first album I made in 53-odd years where I didn't put headphones on. I got a kick out of that.

It was a very comfortable, beautiful experience in the middle of a frightening pandemic. I thought Daryl [Hannah]captured it beautifully in the film. I'm really glad that's going to come out and be shown because it really does capture the comfort and familiarity, high up in the Rockies.

When you think back to the After the Gold Rush days, what comes to mind?

I met Neil when I was 17, at the Cellar Door. Shortly after I met him on Crazy Horse's first tour, I was out in California. I looked Neil up. True to his word, he took me under his wing. He introduced me to David Briggs, his producer. Long story short, after a lot of Hollywood misadventure, I moved in with David in Topanga Canyon. So, I saw a lot of Neil.

They were my big brother mentors at a very young age. They were very encouraging and very honest. I remember my band, Grin, became the house band at the Topanga Canyon Corral. Neil came down and jammed with us one night and we really hit it off and were playing great.

So, the next day, I was at his house with David Briggs. And we were feeling pretty good, you know? Neil and David were telling us how good the drummer was and how much Neil enjoyed playing with us. Being the hard-ass, show-biz, music-biz friends they were, they said, "The band's pretty good, but you need a better bass player."

I was crestfallen because we were a team — a family. But I was only 17, and I had Neil Young and David Briggs — who had moved me into his home with the plan of getting me a record deal and producing us — what are you going to say to that? "Oh, you guys don't know what you're talking about?" So, we got our bass player, Bob Gordon. Sadly, we lost Bob a number of years ago.

But it was just that kind of thing. There was comfort in their relentless honesty mixed with encouragement that I always felt working with Neil. We had many chapters — Tonight's the Night. In between that and After the Gold Rush, we did the Crazy Horse album. The Trans album and tour in the '80s. "MTV Unplugged" in the '90s. More recently, Colorado, and now the new album, Barn.

And how did you end up joining the E Street Band?

Through the years, I'd go see Bruce play a lot. And in '84, when Steve decided to go solo, to my great fortune, I had an audition — I look at it that way; Bruce wouldn't call it that. But we jammed for a couple of days, and it was just five weeks before opening night. So, it was kind of a hairy thing.

I remember I was 18, driving with David. We used to crank Creedence Clearwater driving through the hills of Topanga in a VW Bug. I remember saying, "David, it's so nice to not be a bandleader every day. There are a lot of nonmusical issues that go along with bandleading that disappear."

So, I was very young when I realized [the value of] taking a break from bandleading and just being in a great band. Neil and Bruce, they're really hands-off. They don't direct you very much. They like you to come up with ideas. They might add a suggestion here and there, but there's a lot of freedom that's very similar between the two. They don't mind rough edges and seat-of-your-pants. Neil's maybe taken that to an extreme more than anybody.

Especially on Tonight's the Night.

That one was an anti-production record. David Briggs and Warner just said, "Stay down in it. We don't want you doing the songs too well, but you're still going to be singing and playing. And when Neil gets the right vocal, you're done. No one's going to be allowed to change the notes."

It was a great, dark record. We kind of call it "the wake album," because all our heroes and friends were dying. It was a dark time, and I thought it was a very commiserative, healing project despite the darkness of it.

Bruce and Neil are highly iconoclastic, individualistic artists. What is it about your personality and musicianship that allows you to mesh so well with them?

This is also true with Ringo Starr, who I've been blessed to play with in his first two All-Starr Bands — I wouldn't be a musician if it weren't for the Beatles! I grew up playing classical accordion for 10 years. I'd probably be at a Holiday Inn Express lounge playing the quarter-box, doing hits of the day.

But thanks to the Beatles — and the Stones are amazing, but at the top of the list is the Beatles — I found a crazy, lifesaving love of music that sustained me and still does. I think music is the planet's sacred weapon, really. Billions of souls turn to it.

On the Born in the U.S.A. tour, we went to a birthday party late at night with Ringo, and I got to jam with him. Late at night, having drinks, he gave me his phone number, so I began calling him every few weeks and establishing a friendship. Five years later, he called me in L.A. and told me about his All-Starr Band, so he could get back out there and be a drummer and sing and play. Kind of a round-robin thing.

But back to your original question: there's something they have in common. They quickly pull you out of "Oh my lord, I'm playing with a Beatle," or "Geez, Neil Young — look at his body of work," or Bruce. They're such natural "band" musicians. They're down in it. They're in the music.

Again, because of the freedom that's given, it's positive pressure, like, "Hey, I don't know what we should play. Surprise me. Come up with something great." David Briggs used to say, "Just be great or be gone." Like, "We think you're great. Figure it out."

I love your touch with Crazy Horse — sometimes, it seems like you're barely touching the strings, offering a subtle power. What's your guitar philosophy?

I fingerpick a lot, and there's a gentleness you can get from your flesh. The thumb pick is like a bore — it's very thick, no give. There's a harshness to it. A flatpick has a gentler sound to it. So, I'll use my fingers to get the gentler sound. And with the thumb, you don't have to hit it too hard, and you get quite a percussive thing — which, of course, lends itself to some harmonic playing.

It depends on the song. If we're doing "Shut it Down," I'm starting to bang with the thumb pick, which is very percussive. Then, you turn around and have a beautiful song like "Green is Blue," which is one of the great climate-change songs ever written. Most of it, I barely touch the strings with the thumb pick. Most of it is played with my fingertips. Whatever the mood is.

What was it like to be around Danny? Neil's written very affectionately and effusively about him, sometimes calling him more talented than himself.

Danny was extraordinary. Neil's got such a great vibrato, but it was really Danny who sang with that shaky, kind of Bee Gees vibrato. You can hear it so well in "I Don't Want to Talk About It," from the first Crazy Horse record and in a lot of his singing in the early records with Neil. He was very powerful — kind of a surfer, California dude. A brilliant, soulful musician. Very game for anything.

Of course, Danny was getting better and more creative and getting ready to make the first Crazy Horse album. It was at that point I joined the band with Jack Nitzsche that [Danny] was getting more affected by alcohol and drugs. It was kind of sad to watch him in decline because he was this real musical hero — all of ours, including Neil's.

At one point, after we made the Crazy Horse record, Danny went back to Maryland. He and I were talking about joining my band Grin as another member. He lived with us for a while. I remember we were at Georgetown University, waiting to see Roy Buchanan. We left Danny; he didn't want to come into town. He was getting pretty sick back then.

We were in the audience waiting for Roy to come on, but the lights were still up. Someone comes to the mic and pages me. So, I go backstage, there was a landline. Our head of road crew, who was living in this funky place in the country in Urbana, Maryland, said, "Man, I'm so sorry. I lost Danny!" I'm like, "What do you mean, you lost Danny?" He was supposed to watch Danny.

Danny was roaming the Maryland countryside, looking for drugs. We were like, "Oh my god! If he walks up to the wrong home, someone's going to shoot him!" We rushed back out there, looked around and found him wandering around. It got to a point where I was like, "Danny, man… you're so ill. I don't think you can handle this schedule. We're on tour in clubs seven days a week. I'd love you to be in the band, but you've got to get well, man."

He understood and was bummed out, but it never happened. That was the great tragedy when we were making the album. Danny couldn't be bothered to tune his guitar. I tuned it for him. It was lucky that we got that great album done. Everybody, including Neil, wanted to give Danny a shot working on the Harvest record, but he just never did it.

He was, in the beginning, very confident. He challenged Neil on guitar. The interplay they created together — and Poncho [Sampedro] carried that on so great for 37 years. Neil and Danny wrote the book on that two-guitar grunge — and the pretty stuff, too. And then the voices together were just extraordinary.

At the end of the day, he just became a casualty of alcohol and drugs. It was a great loss to all of us.

I imagine people didn't understand mental health and addiction back then like we do now.

Back then, the rehabs were insane asylums. I will say that while we were making Barn — and same with Colorado — Danny, David Briggs, Ben Keith, Elliot Roberts — they were all fresh on our minds. Elliot was a sudden loss recently, which broke all our hearts — especially Neil's. Elliot was in the room when I met him when I was 17, all those years ago.

That's part of life, of course, but it was a rough hit for all of us, [being] in a band with such powerful figures. You never quite get over it.

Neil's cosmology is populated with these departed, incredibly consequential figures.

It's just kind of endless. But that's life. It's a rough part of life, and you never get too great at navigating it. But it does really help to have the other guys there.

Ringo and I talk about the first All-Starr Band in '89, which might have been the greatest cast of musical characters in history. There's only a few of us left: me, Joe Walsh, Jim Keltner and Ringo. Dr. John, Billy Preston, Clarence Clemons, Rick Danko, Levon Helm… talk about a band!

From the Tonight's the Night band — minus Ben Keith — four out of five of us are still standing. That's pretty good for a bunch of old guys.

Do you consider yourselves survivors? You mentioned Joe Walsh and Ringo — those guys could have gone the way of Danny, but didn't.

Ringo's been very open about his sobriety. On the tour in '89, I was just a year ahead of Ringo, cleaning up my act. I've been clean and sober for 34 years.

The message is: If you've got a problem with drugs or alcohol, there's help. There's a lot more now than there used to be, but you ain't gonna get it if you don't look for it. I'm really proud of people like Joe and Ringo, who got the help and they're out singing and playing.

You can talk it around, talk it to death — but at the end of the day, if you're struggling with issues like that, you only have three choices: You get cleaned up, you get locked up or you get covered up. That's it. Every day, you pick one.

Photo: Tim P. Whitby/Getty Images for Disney+

list

10 Facts About Jon Bon Jovi: A Friendship With Springsteen, Philanthropy, Football Fanaticism & More

Ahead of the band's new album 'Forever,' out June 7, and a new Hulu documentary, "Thank you, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story," read on for 10 facts about the GRAMMY-winning group and its MusiCares Person Of The Year frontman.

Bon Jovi have officially been in the cultural conversation for five decades — and it looks like we'll never say goodbye.

The band's self-titled debut album was unleashed upon the world in 1984, and lead single "Runaway" made some waves. Yet the New Jersey group didn't truly break through until their third album, the 12 million-selling Slippery When Wet. By the late 1980s, they were arguably the biggest rock band in the world, selling out massive shows in arenas and stadiums.

Since, Bon Jovi releases have consistently topped album charts (six of their studio albums hit No. 1). A big reason for their continued success is that, unlike a majority of their ‘80s peers, frontman Jon Bon Jovi made sure that they adapted to changing times while retaining the spirit of their music — from the anthemic stomp of 1986’s "Bad Medicine" to the Nashville crossover of 2005’s "Who Says You Can’t Go Home." It also doesn’t hurt that the 2024 MusiCares Person Of The Year has aged very gracefully; his winning smile and charismatic personality ever crush-worthy.

Their fifth decade rocking the planet has been marked by many other milestones: The release of a four-part Hulu documentary, "Thank you, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story"; Bon Jovi's 16th studio album Forever, and fan hopes for the return of original guitarist Richie Sambora who left unexpectedly in 2013. Despite all of these positive notes, there is an ominous cloud hanging over the group as their singer had to undergo vocal surgery following disappointing, consistently off-key performances on the group's 2022 U.S. tour. Even afterward, he remains unsure whether he’ll be able to tour again. But Bon Jovi remains popular and with Sambora expressing interest in a reunion, it's plausible that we could see them back on stage again somehow.

Jon Bon Jovi has also had quite a multifaceted career spun off of his success in music, as shown by the following collection of fascinating facts.

Jon Bon Jovi Sung With Bruce Springsteen When He Was 17

By the time he was in high school, Jon Bongiovi (his original, pre-fame last name) was already fronting his first serious group. The Atlantic City Expressway was a 10-piece with a horn section that performed well-known tunes from Jersey acts like Bruce Springsteen and Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes.

They regularly played The Fast Lane, and one night Bruce Springsteen was in the audience. To Bon Jovi’s surprise, The Boss jumped onstage to join them. The two later became good friends — during his MusiCares performance, Bon Jovi introduced Springsteen as "my mentor, my friend, my brother, my hero."

Jon Recorded Bon Jovi’s First Hit Before The Band Formed

Although "Runaway" was the debut single and lone Top 40 hit from Bon Jovi's first two albums, it was recorded as a professional demo back in 1982.

Bon Jovi got a gig as a gopher at Power Station, the famed studio co-owned by his second cousin Tony Bongiovi where artists like the Rolling Stones, Diana Ross, and David Bowie recorded. (He watched even watched Bowie and Freddie Mercury record the vocals for "Under Pressure.")

The future rockstar cut "Runaway" (which was co-written mainly by George Karak) and other demos with session musicians — his friend, guitarist Aldo Nova, Rick Springfield/John Waite guitarist Tim Pierce, Springsteen keyboardist Roy Bittan, bassist Hugh McDonald (a future Bon Jovi member), and Scandal drummer Frankie LaRocca. The song first appeared on a WAPP compilation under his name, but then it was placed on Bon Jovi’s debut album. When the video for "Runway" was created nearly two years later, members of Bon Jovi were miming to other people’s performances.

Although it is a classic, original guitarist Richie Sambora hates it and never wants to play it again.

He Eloped With His High School Sweetheart In April 1989

During the band’s world tour in support of New Jersey, Bon Jovi and Dorothea Hurley spontaneously eloped in a quickie wedding in Vegas. His bandmates and management were shocked to find this out; the latter probably feared that his ineligible bachelor status would harm their popularity with their ardent female fans. But it simply played more into his more wholesome image that differed from other hard rockers of the time.

In May 2024, Bon Jovi’s son Jake secretly married "Stranger Things" actor Millie Bobby Brown. It was like history repeating itself, except this time family was involved.

Listen: Revisit Jon Bon Jovi's Greatest Hits & Deep Cuts Ahead Of MusiCares' Person Of The Year 2024 Gala

The Bongiovi Family Is Part Of The Bon Jovi Family

Back in the ‘80s, parents often didn’t like their kids’ music. However, Bon Jovi’s parents completely supported his. Mother Carol Bongiovi often chaperoned his early days when he was an underaged kid playing local clubs and bars in New Jersey. Father Jon Sr. was the group’s hair stylist until their third album, Slippery When Wet. He created his son's signature mane.

Jon’s brother Matthew started as a production assistant in the band’s organization, then worked for their management before becoming his brother’s head of security and now his tour manager. His other brother Anthony became the director of a few Bon Jovi concert films and promo clips. He’s also directed concert films for Slayer and the Goo Goo Dolls.

Bon Jovi Is A Regular In Television & Film

After writing songs for the Golden Globe-winning "Young Guns II soundtrack (released as the solo album Blaze Of Glory) and getting a cameo in the Western’s opening, Bon Jovi was bitten by the acting bug. He studied with acclaimed acting coach Harold Guskin in the early ‘90s, then appeared as the romantic interest of Elizabeth Perkins in 1995's Moonlight and Valentino.

In other movies, Bon Jovi played a bartender who’s a recovering alcoholic (Little City), an ex-con turning over a new leaf (Row Your Boat), a failed father figure (Pay It Forward), a suburban dad and pot smoker (Homegrown), and a Navy Lieutenant in WWII (U-571). The band’s revival in 2000 slowed his acting aspirations, but he appeared for 10 episodes of "Ally McBeal," playing her love interest in 2002.

Elsewhere on the silver screen, the singer has also portrayed a vampire hunter (Vampiros: Los Muertos), a duplicitous professor (Cry Wolf), the owner of a women’s hockey team (Pucked), and a rock star willing to cancel a tour for the woman he loves (New Year’s Eve). He hasn’t acted since 2011, but who knows when he might make a guest appearance?

Jon Bon Jovi Once Co-Owned A Football Team

In 2004, Bon Jovi became one of the co-founders and co-majority owner of the Philadelphia Soul, which were part of the Arena Football League (AFL). (Sambora was a minority shareholder.) The team name emerged in a satirical scene from "It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia" during which Danny DeVito’s character tries to buy the team for a paltry sum and twice butchers the singer’s name.

Jon stuck with the team until 2009, a year after they won Arena Bowl XXII, defeating the San Jose SaberCats. He then set his eyes on a bigger prize, the Buffalo Bills, aligning himself with a group of Toronto investors in 2011. One of his biggest competitors? Donald Trump, who ran a smear campaign alleging that the famed singer would move the team to Toronto.

In the end, neither man purchased the team as they were outbid by Terry and Kim Pegula, who still own the Bills today.

Jon & Richie Sambora Wrote Songs For Other Artists

Having cranked out massive hits with songwriter Desmond Child, Bon Jovi and Sambora decided to write or co-write songs for and with other artists.

In 1987, they co-wrote and produced the Top 20 hit "We All Sleep Alone" with Child for Cher, and also co-wrote the Top 40 hit "Notorious" with members of Loverboy. In 1989, the duo paired up again Loverboy guitarist Paul Dean for his solo rocker "Under The Gun" and bequeathed the New Jersey outtake "Does Anybody Really Fall in Love Anymore?" (co-written with Child and Diane Warren) to Cher.

The Bon Jovi/Sambora song "Peace In Our Time" was recorded by Russian rockers Gorky Park. In 1990, Paul Young snagged the New Jersey leftover "Now and Forever," while the duo penned "If You Were in My Shoes" with Young, though neither song was released. In 2009, Bon Jovi and Sambora were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame for their contributions to music.

Jon Bon Jovi Once Ran His Own Record Label

For a brief time in 1991, he ran his own record label, Jambco, which was distributed through Bon Jovi’s label PolyGram Records. The only two artists he signed were Aldo Nova and Billy Falcon, a veteran singer/songwriter who became Bon Jovi's songwriting partner in the 2000s. Neither of their albums (Aldo Nova’s Blood On The Bricks and Billy Falcon’s Pretty Blue World) were big sellers, and the label folded quickly when they began losing money.

Still, the experience gave Bon Jovi the chance to learn about the music business. That experience helped after he fired original manager Doc McGhee in 1991 and took over his band’s managerial reins until 2015.

Bon Jovi's Vocal Issues Aren't New

Although Jon Bon Jovi's vocal problems have become a major issue recently, they stem back to the late 1980s. It's doubtful as to whether Jon had proper vocal training for a rock band at the start.

The group did 15-month tours to support both the Slippery When Wet and New Jersey albums. Near the end of the grueling Slippery tour, Bon Jovi was getting steroid injections because his voice was suffering.

While his voice held up into the 2000s, it has become apparent over the last decade that his singing is rougher than it used to be. As shown in the Hulu new documentary, the singer has been struggling to maintain his voice. It’s natural for older rock singers to lose some range — it’s been very rare to hear him sing any of the high notes in "Livin’ On A Prayer" over the last 20 years — but he admitshe is unsure whether he can ever tour again, even with recent surgery.

Bon Jovi Has Been A Philanthropist For Over Three Decades

Back in the 1980s, the upbeat Bon Jovi made it clear that they were not going to be a toned-down political band. But in the ‘90s, he and the band toned down their look, evolved their sound, and offered a more mature outlook on life.

Reflecting this evolved viewpoint, the band started an annual tradition of playing a December concert in New Jersey to raise money for various charitable causes; the concert series began in 1991 and continued with the band or Jon solo through at least 2015. The group have played various charitable concert events over the years including the Twin Towers Relief Benefit, Live 8 in Philadelphia, and The Concert For Sandy Relief.

By the late 2000s, Jon and Dorothea founded the JBJ Soul Kitchen to serve meals at lower costs to people who cannot afford them. COVID-19 related food shortages led the couple to found the JBJ Soul Kitchen Food Bank. Their JBJ Soul Foundation supports affordable housing and has rebuilt and refurbished homes through organizations like Project H.O.M.E., Habitat For Humanity, and Rebuilding Together.

While he may be a superstar, Jon Bon Jovi still believes in helping others. For his considerable efforts, he was honored as the 2024 MusiCares Person Of The Year during 2024 GRAMMY Week.

Photo: Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images

list

How Bruce Springsteen's 'Born In The U.S.A.' Changed Rock History — And The Boss' Own Trajectory

On the 40th anniversary of Bruce Springsteen's seminal album detailing working class life Reagan era America, reflect on the many ways 'Born In The U.S.A.' impacted pop and rock music.

Bruce Springsteen himself might not be particularly enthusiastic about his seventh studio effort, Born In The U.S.A. ("a group of songs about which I've always had some ambivalence"). But for the record buyers of 1984 – and indeed much of the decade thereafter – it was a towering achievement in combining classic and contemporary American rock.

Born In The U.S.A. was co-produced with Jon Landau, Chuck Plotkin, and E Street Band member Steven Van Zandt, and represented a complete divergence from his previous release, the acoustic affair Nebraska. Audiences didn't seem to mind the change in tone: The 12-track LP spent seven weeks atop the Billboard 200 and sold more than 17 million copies in America alone.

It also equaled the record set by Michael Jackson's Thriller by spawning seven consecutive U.S. Top 10 hits, including the oft-misunderstood title track, "I'm On Fire," and his highest-charting, "Dancing in the Dark." (The latter netted The Boss his first GRAMMY Award, for Best Rock Vocal Performance, Male.) Born's themes of working-class life in the Ronald Reagan era struck a chord with homegrown audiences, albeit occasionally for unintended reasons, and picked up a coveted Album Of The Year nod at the 1985 GRAMMYs.

But there's more to Born In The U.S.A.'s story than blockbuster sales and critical acclaim. It also changed the course of rock music in several ways, whether reigniting America's love of the genre, proving that synths and guitars could work together in perfect harmony, or simply popularizing a new way to hear it. Ahead of its 40th anniversary, here's a look at why the record fully deserves its status as an all-time great.

It Revolutionized The Sound Of Heartland Rock

Already hailed as a progenitor of the blue-collar, rootsy sound known as heartland rock, Springsteen once again proved to be something of a revolutionary when he added synths into the mix. Born In The U.S.A. continually puts pianist Roy Bittan's skills to great use — whether he's echoing the whistle that haunts the narrator of "Downbound Train," giving "I'm On Fire" its ethereal sheen, or imbuing "Dancing In The Dark" with a glowing warmth.

Born In The U.S.A. helped codify synths as a key component of the decade's rock sound. Within a few years, most of The Boss' peers had enjoyed synth-based success: Don Henley with Building the Perfect Beast, Tom Petty with Southern Accents, as well as Robbie Robertson's self-titled debut. Even The Boss' hero, Bob Dylan, went electric again on Empire Burlesque. And you can hear its modern-day influence in the likes of the Killers, Kurt Vile, and, most notably, proud Springsteen acolytes The War on Drugs.

It Bid Farewell To Rock's Most Iconic Backing Band

With their uncanny ability to capture and expand upon his musical vision, The E Street Band have been as integral to Springsteen's success as The Boss himself. The likes of bassist Garry Tallent, saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and drummer Max Weinberg were responsible for the Wall of Sound that enveloped 1975 breakthrough Born to Run, while 1980's The River was a concerted attempt to replicate their prowess on the stage in the studio.

But while they provided occasional backing on 1987 follow-up Tunnel of Love, Born In The U.S.A. was the last time Springsteen fully utilized their talents until 2002's return-to-form The Rising. It also proved to be a proper farewell to Van Zandt, who left the set-up halfway through recording to pursue a solo career. The constant whoops and cheers, however, suggests that all parties were determined to end things on a celebratory note.

It Turned Springsteen Into An MTV Icon

Springsteen had only previously released one music video, and he didn't even make an appearance, with 1982's "Atlantic City" consisting solely of austere images of the titular location. But keen to show off the muscular physique he'd developed during the following two years, The Boss made five videos for Born In The U.S.A., and bagged some impressive names to help him land that all-important MTV play.

Scarface director Brian De Palma helmed its most famous, the "Dancing in the Dark" promo in which Springsteen plucked a then-unknown Courteney Cox from the crowd. Indie favorite John Sayles pulled triple duty, directing the performance-based video for the title track and developing the narrative treatments for "I'm On Fire" (Springsteen plays car mechanic tempted by affair with married customer) and "Glory Days" (Springsteen bonds with son via baseball). Boasting footage from the Born In The U.S.A. tour, "My Hometown" rounded off the whole audio-visual campaign which was twice recognized at the VMAs.

It Kickstarted A CD Revolution

Although compact discs had been around for several years, Born In The U.S.A. was — fittingly, considering its title and blue collar themes — the first to be manufactured in America. Within just a few years, the homegrown CD market had skyrocketed from virtually zero to more than $930 million. And with at least 17 million copies sold domestically overall, it seems reasonable to suggest that Springsteen's seventh LP was responsible for a significant percentage.

No doubt that its iconic front cover — shot by celebrated photographer Annie Leibovitz — helped the album stand in record stores. Shot from behind with Springsteen clad in denim, posing in front of the Stars and Stripes, Born In The U.S.A. provided audiences with one of the decade's most recognizable images. Explaining the creative decision to ignore his Hollywood action hero looks, The Boss told Rolling Stone, "The picture of my ass looked better than the picture of my face."

It Spawned A Game-Changing Tour

If you need any proof of how stratospheric Born In The U.S.A. sent Springsteen's career, just look at its accompanying tour. With 156 dates across North America, Asia, Europe, and Australia, the tour raked in approximately $90 million. (It remained the decade's highest-grossing rock tour until Pink Floyd's A Momentary Lapse of Reason concluded four years later.)

Springsteen's success also appeared to convince David Bowie and Tina Turner that solo artists could handle a stadium crowd as well as any band.

The Born In The U.S.A. trek was monumental for several other reasons: it was the first to feature new E Street Band member Nils Lofgren and Springsteen's future wife Patti Scialfa. It established his long-running love affair with the now-demolished Giants Stadium, a New Jersey venue returned to 23 times. The tour formed more than half of Springsteen's Live: 1975-85 album that topped the Billboard 200 for four weeks in 1986. Until Garth Brooks' Double Live 12 years later, Live: 1975-85 the highest-selling live album ever.

It Celebrated Male Friendship

Springsteen has never been afraid to be vulnerable when it comes to an area most rock musicians seem afraid to address: the importance of male friendship. "Ghosts," for example, is a heartfelt dedication to all the bandmates he'd lost over the years, while "This Hard Land" is a tale of brotherhood inspired by his love of western maestro John Ford. But it was on Born In The U.S.A. where The Boss first showed that songs about entirely platonic love can be as emotively powerful as the more romantic side.

Indeed, the ambiguous gender on "Bobby Jean" has led many to believe the concert staple is a testament to his relationship with Van Zandt. And "No Surrender" appears to revel in the camaraderie they shared back in their younger days. Foo Fighters ("The Glass"), the Walkmen ("Heaven"), and Death Cab for Cutie ("Wheat Like Waves") have all since followed Springsteen's lead by opening up about their all-male bonds.

It Ushered In A Wave of Presidential Appropriation

It's not something that Springsteen will be shouting from the rooftops about. But Born In The U.S.A. — specifically its famously misunderstood title track — essentially ushered in the trend of presidential candidates co-opting chart hits regardless of the artist's political leanings. Indeed, long before the likes of George W. Bush vs. Sting, Sarah Palin vs. Gretchen Peters, and Donald Trump vs. Neil Young and John Fogerty (among many others), The Boss took umbrage with Ronald Reagan's plans to use "Born In The USA" for his 1984 reelection campaign.

Despite Springsteen's flat-out refusal, he was still celebrated by Reagan in a stump speech, declaring that America's future "rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire: New Jersey's own Bruce Springsteen." And both Pat Buchanan and Bob Dole, also seemingly mistaking its rally cry against the treatment of Vietnam War veterans for a patriotic anthem, cheekily used the track before its writer got wind and shut them down.

It Revived America's Love Of American Rock

While Eagles' Hotel California, Fleetwood Mac's Rumors, and Boston's self-titled debut had all racked up colossal sales in the '70s, Springsteen's commercial opus was the first guitar-oriented U.S. release to achieve similar numbers in the '80s. By the end of the decade, Guns N' Roses' Appetite for Destruction and Journey's Greatest Hits were also approaching the 20 million mark, while Bryan Adams' Reckless, Van Halen's 5150, and Bon Jovi's Slippery When Wet were just a few of the domestic rock efforts that immediately followed in its chart-topping footsteps.

And while the use of synths brought Springsteen's sound into the '80s, The Boss didn't forget about his earthier roots. Born In The U.S.A. is also steeped in the classic sounds of American rock, from the honky tonk leanings of "Darlington County" and rockabilly of "Workin' On The Highway" to the front porch folk of "My Hometown." Its lyrical content might not always have been patriotic, but its accompanying music was as American as apple pie.

Songbook: How Bruce Springsteen's Portraits Of America Became Sounds Of Hope During Confusing Times

Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images

list

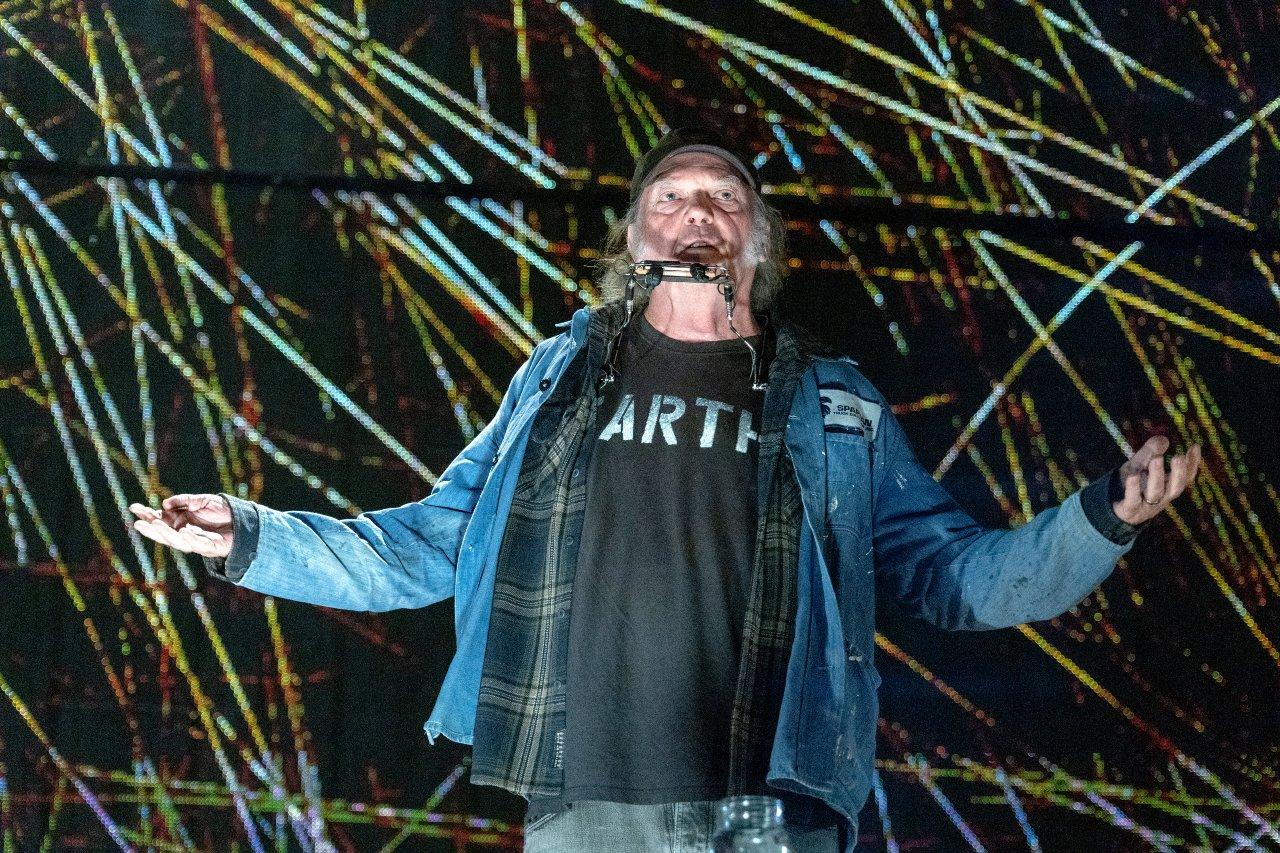

Inside Neil Young & Crazy Horse's 'F##IN' UP': Where All 9 Songs Came From

Two-time GRAMMY winner and 28-time nominee Neil Young is back with 'F##IN' UP,' another album of re-recorded oldies, this time with Crazy Horse. But if that sounds like old hat, this is Young — and the script is flipped yet again.

Neil Young has never stopped writing songs, but for almost a decade, he's been stringing together old songs like paper lanterns, and observing how their hues harmonize.

2016's Earth, where live performances of ecologically themed songs were interspersed with animal and nature sounds, was certainly one of his most bizarre. 2018's Paradox, a soundtrack to said experimental film with wife/collaborator Darryl Hannah, took a similarly off-kilter tack.

He's played it straight for others. Homegrown and Chrome Dreams were recorded in the ‘70s, then shelved, and stripped for parts. Both were finally released in their original forms over the past few years; while most of the songs were familiar, it was fascinating envisioning an alternate Neil timeline where they were properly released.

Last year's Before and After — likely recorded live on a recent West Coast solo tour — was less a collection of oldies than a spyglass into his consciousness: this is how Young thinks of these decades-old songs at 78.

Now, we have F##IN' UP, recorded at a secret show in Toronto with the current version of Crazy Horse. (That's decades-long auxiliary Horseman Nils Lofgren, or recent one Micah Nelson on second guitar, with bassist Billy Talbot and drummer Ralph Molina from the original lineup.)

Every song's been christened an informal new title, drawn from the lyrics; the effect is of turning over a mossy rock to reveal its smooth, untouched inverse.

It's named after a fan favorite from 1990's Ragged Glory; in fact, all of its songs stem from that back-to-the-garage reset album. Of course, that's how they relate; they're drawn from a single source. But Young being Young, it's not that simple: some of these nine songs have had a long, strange journey to F##IN' UP.

Before you see Neil and the Horse on tour across the U.S., here's the breakdown.

"City Life" ("Country Home")

The Horse bolts out of the gate with "Country Home," from Ragged Glory; in 2002's Shakey, Young biographer Jimmy McDonough characterized it as "a tribute to the [Broken Arrow] ranch that is surely one of Young's most euphoric songs."

As McDonough points out, it dates back to the '70s, around the Zuma period. With spring sprung, another go-round of this wooly, bucolic rocker feels right on time.

"Feels Like a Railroad (River Of Pride)" ("White Line")

Like "Country Home," "White Line" also dates back to the mid-'70s — but we've gotten to hear the original version, as released on 2020's (via-1974-and-'75) Homegrown.

The original was an aching acoustic duet with the Band's Robbie Robertson; when the Horse kicks it in the ass, it's just as powerful. (As for Homegrown, it was shelved in favor of the funereal classic Tonight's the Night.)

"Heart Of Steel" ("F##in' Up")

As with almost every Horse jam out there, the title track to F##IN' UP defies analysis. Think of a reverse car wash: the uglier and grungier the Horse renders this song, the more beautiful it is.

"Broken Circle" ("Over and Over")

Title-wise, it’s excusable if you mix this one up with "Round and Round," a round-robin deep cut from the first Neil and the Horse album, 1969's Everybody Knows This is Nowhere. Rather, this is yet another sturdy, loping rocker from Ragged Glory.

"Valley of Hearts" ("Love to Burn")

As McDonough points out in Shakey, "Love to Burn" has an acrid, accusatory edge that might slot it next to "Stupid Girl" in the pantheon of Neil's Mad At An Ex jams: "Where you takin' my kid / Why'd you ruin my life?"

But the chorus salves the burn: "You better take your chance on love / You got to let your guard down."

"She Moves Me" ("Farmer John")

The only non-Young original on F##IN' UP speaks to his lifelong inspiration from Black R&B music — a flavor OG guitarist Danny Whitten brought to the Horse, and has persisted in their sound decades after his tragic death.

Don "Sugarcane" Harris and Dewey Terry wrote "Farmer John" for their duo Don and Dewey; it dates back to Young's pre-Buffalo Springfield surf-band the Squires.

"Not much of a tune, but we made it happen," Bill Edmundson, who drummed with the band for a time, said in Shakey. "We kept that song goin' for 10 minutes. People just never wanted it to end." Sound familiar?

"Walkin' in My Place (Road of Tears)" ("Mansion on the Hill")

"Mansion on the Hill" was one of two singles from Ragged Glory; "Over and Over" was the other.

While it's mostly just another Ragged Glory rocker with tossed-off, goofy lyrics, Young clearly felt something potent stirring within its DNA; back in the early '90s, he stripped it down for acoustic guitar on the Harvest Moon tour.

"To Follow One's Own Dream" ("Days That Used To Be")

Briefly called "Letter to Bob," "Days That Used to Be" is Dylanesque in every way — from its circular, folkloric melody to its shimmering, multidimensional lyrics.

"But possessions and concession are not often what they seem/ They drag you down and load you down in disguise of security" could be yanked straight from Blonde on Blonde.

For more of Young's thoughts on Bob Dylan, consult "Twisted Road," from his 2012 masterpiece with the Horse, Psychedelic Pill. "Poetry rolling off his tongue/ Like Hank Williams chewing bubble gum," he sings, sounding like a still-awestruck fan rather than a peer.

"A Chance On Love" ("Love and Only Love")

Possibly the most resonant song on Ragged Glory — and, by extension, F##IN' UP — "Love and Only Love" is like the final boss of the album, where Young battles hate and division with Old Black as his battleaxe.

(Also see: Psychedelic Pill's "Walk Like a Giant," where Young violently squares up with the '60s dream.)

The 15-minute workout (which feels like Ramones brevity in Horse Time) It's a fitting end to F##IN' UP. There will be more Young soon. A lot more, his team promises. But although his output is a firehose, take it under advisement to savor every last drop.

Inside Neil Young's Before and After: Where All 13 Songs Came From

list

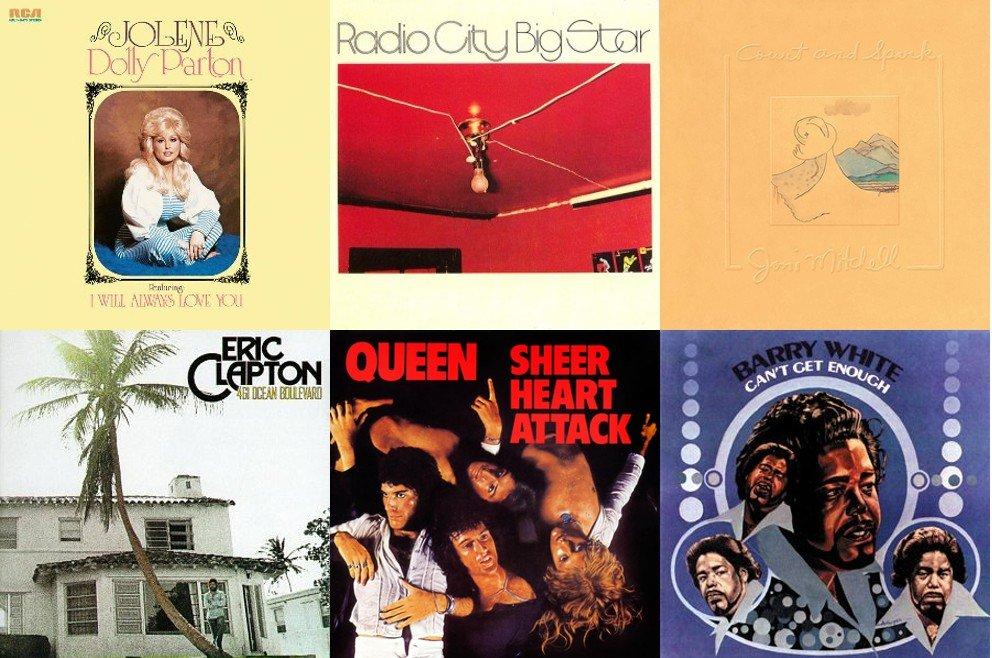

21 Albums Turning 50 In 2024: 'Diamond Dogs,' 'Jolene,' 'Natty Dread' & More

Dozens of albums were released in 1974 and, 50 years later, continue to stand the test of time. GRAMMY.com reflects on 21 records that demand another look and are guaranteed to hook first-time listeners.

Despite claims by surveyed CNN readers, 1974 was not a year marked by bad music. The Ramones played their first gig. ABBA won Eurovision with the earworm "Waterloo," which became an international hit and launched the Swedes to stardom. Those 365 days were marked by chart-topping debuts, British bangers and prog-rock dystopian masterpieces. Disenchantment, southern pride, pencil thin mustaches and tongue-in-cheek warnings to "not eat yellow snow" filled the soundwaves.

1974 was defined by uncertainty and chaos following a prolonged period of crisis. The ongoing OPEC oil embargo and the resulting energy shortage caused skyrocketing inflation, exacerbating the national turmoil that preceded President Nixon’s resignation following the Watergate scandal. Other major events also shaped the zeitgeist: Stephen King published his first novel, Carrie, Muhammad Ali and George Foreman slugged it out for the heavyweight title at "The Rumble in the Jungle," and People Magazine published its first issue.

Musicians reflected a general malaise. Themes of imprisonment, disillusionment and depression — delivered with sardonic wit and sarcasm — found their way on many of the records released that year. The mood reflects a few of the many reasons these artistic works still resonate.

From reggae to rock, cosmic country to folk fused with jazz, to the introduction of a new Afro-Trinidadian music style, take a trip back 18,262 days to recall 20 albums celebrating their 50th anniversaries in 2024.

Joni Mitchell - Court & Spark

Joni Mitchell’s Court & Spark is often hailed as the pinnacle of her artistic career and highlights the singer/songwriter’s growing interest in jazz, backed by a who’s who of West Coast session musicians including members of the Crusaders and L.A. Express.

As her most commercially successful record, the nine-time GRAMMY winner presents a mix of playful and somber songs. In an introspective tone, Mitchell searches for freedom from the shackles of big-city life and grapples with the complexities of love lost and found. The record went platinum — it hit No.1 on the Billboard charts in her native Canada and No. 2 in the U.S., received three GRAMMY nominations and featured a pair of hits: "Help Me" (her only career Top 10) and "Free Man in Paris," an autobiographical song about music mogul David Geffen.

Gordon Lightfoot - Sundown

In 2023 we lost legendary songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. He left behind a treasure trove of country-folk classics, several featured on his album Sundown. These songs resonated deeply with teenagers who came of age in the early to mid-1970s — many sang along in their bedrooms and learned to strum these storied songs on acoustic guitars.

Recorded in Toronto, at Eastern Sound Studios, the album includes the only No.1 Billboard topper of the singer/songwriter’s career. The title cut, "Sundown," speaks of "a hard-loving woman, got me feeling mean" and hit No. 1 on both the pop and the adult contemporary charts.

In Canada, the album hit No.1 on the RPM Top 100 in and stayed there for five consecutive weeks. A second single, "Carefree Highway," peaked at the tenth spot on the Billboard Hot 100, but hit No.1 on the Easy Listening charts.

Eric Clapton - 461 Ocean Boulevard

Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard sold more than two million copies worldwide. His second solo studio record followed a three-year absence while Clapton battled heroin addiction. The record’s title is the address where "Slowhand" stayed in the Sunshine State while recording this record at Miami’s Criteria Studios.

A mix of blues, funk and soulful rock, only two of the 10 songs were penned by the Englishman. Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s "I Shot the Sheriff," was a massive hit for the 17-time GRAMMY winner and the only No.1 of his career, eclipsing the Top 10 in nine countries. In 2003, the guitar virtuoso’s version of the reggae song was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

Lynyrd Skynyrd - Second Helping

No sophomore slump here. This "second helping" from these good ole boys is a serious serving of classic southern rock ‘n’ roll with cupfuls of soul. Following the commercial success of their debut the previous year, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s second studio album featured the band’s biggest hit: "Sweet Home Alabama."

The anthem is a celebration of Southern pride; it was written in response to two Neil Young songs ("Alabama" and "Southern Man") that critiqued the land below the Mason-Dixon line. The song was the band’s only Top 10, peaking at No. 8 on the Billboard Top 100. Recorded primarily at the Record Plant in Los Angeles, other songs worth a second listen here include: the swampy cover of J.J. Cale's "Call Me The Breeze," the boogie-woogie foot-stomper "Don’t Ask Me No Questions" and the country-rocker "The Ballad of Curtis Loew."

Bad Company - Bad Company

A little bit of blues, a token ballad, and plenty of hard-edged rock, Bad Company released a dazzling self-titled debut album. The English band formed from the crumbs left behind by a few other British groups: ex-Free band members including singer Paul Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke, former King Crimson member bassist Boz Burrel, and guitarist Mick Ralphs from Mott the Hoople.

Certified five-times platinum, Bad Company hit No.1 on the Billboard 200 and No. 3 in the UK, where it spent 25 weeks. Recorded at Ronnie Lane’s Mobile Studio, the album was the first record released on Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label. Five of the eight tracks were in regular FM rotation throughout 1974; "Bad Company," "Can’t Get Enough" and "Ready for Love" remain staples of classic rock radio a half century later.

Supertramp - Crime of the Century

"Dreamer, you know you are a dreamer …" sings Supertramp’s lead singer Roger Hodgson on the first single from their third studio album. The infectious B-side track "Bloody Well Right," became even more popular than fan favorite, "Dreamer."

The British rockers' dreams of stardom beyond England materialized with Crime of the Century. The album fused prog-rock with pop and hit all the right notes leading to the band’s breakthrough in several countries — a Top 5 spot in the U.S. and a No.1 spot in Canada where it stayed for more than two years and sold more than two million copies. A live version of "Dreamer," released six years later, was a Top 20 hit in the U.S.

Big Star - Radio City

As one of the year’s first releases, the reception for this sophomore effort from American band Big Star was praised by critics despite initial lukewarm sales (which were due largely to distribution problems). Today, the riveting record by these Memphis musicians is considered a touchstone of power pop; its melodic stylings influenced many indie rock bands in the 1980s and 1990s, including R.E.M. and the Replacements. One of Big Star’s biggest songs, "September Gurls," appears here and was later covered by The Bangles.

In a review, American rock critic Robert Christgau, called the record "brilliant and addictive." He wrote: "The harmonies sound like the lead sheets are upside down and backwards, the guitar solos sound like screwball readymade pastiches, and the lyrics sound like love is strange, though maybe that's just the context."

The Eagles - On the Border

The third studio record from California harmonizers, the Eagles, shows the band at a crossroads — evolving ever so slightly from acoustically-inclined country-folk to a more distinct rock ‘n’ roll sound. On the Border marks the studio debut for band member Don Felder. His contributions and influence are seen through his blistering guitar solos, especially in the chart-toppers "Already Gone" and "James Dean."

On the Border sold two million copies, driven by the chart topping ballad "Best of My Love" — the Eagles first No.1 hit song. The irony: the song was one of only two singles Glyn Johns produced at Olympic Studios in London. Searching for that harder-edged sound, the band hired Bill Szymczyk to produce the rest of the record at the Record Plant in L.A.

Jimmy Buffett - Livin’ and Dyin in ¾ Time & A1A

Back in 1974, 28-year-old Jimmy Buffett was just hitting his stride. Embracing the good life, Buffett released not just one, but two records that year. Don Grant produced both albums that were the final pair in what is dubbed Buffett’s "Key West phase" for the Florida island city where the artist hung his hat during these years.

The first album, Livin’ and Dyin’ in ¾ Time, was released in February and recorded at Woodland Sound Studio in Nashville, Tennessee. It featured the ballad "Come Monday," which hit No. 30 on the Hot 100 and "Pencil Thin Mustache," a concert staple and Parrothead favorite. A1A arrived in December and hit No. 25 on the Billboard 200 charts. The most beloved songs here are "A Pirate Looks at Forty" and "Trying to Reason with Hurricane Season."

Buffett embarked on a tour and landed some plume gigs, including opening slots for two other artists on this list: Frank Zappa and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Genesis - The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

Following a successful tour of Europe and North America for their 1973 album, Selling England by the Pound, Genesis booked a three-month stay at the historic Headley Grange in Hampshire, a former workhouse. In this bucolic setting, the band led by frontman Peter Gabriel, embarked on a spiritual journey of self discovery that evolved organically through improvisational jams and lyric-writing sessions.

This period culminated in a rock opera and English prog-rockers’s magnum opus, a double concept album that follows the surreal story of a Puerto Rican con man named Rael. Songs are rich with American imagery, purposely placed to appeal to this growing and influential fan base across the pond.

This album marked the final Genesis record with Gabriel at the helm. The divisiveness between the lyricist, Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks came to a head during tense recording sessions and led to Gabriel’s departure from the band to pursue a solo career, following a 102-date tour to promote the record. The album reached tenth spot on the UK album charts and hit 41 in the U.S.

David Bowie - Diamond Dogs

Is Ziggy Stardust truly gone? With David Bowie, the direction of his creative muse was always a mystery, as illustrated by his diverse musical legacy. What is clear is that Bowie’s biographers agree that this self-produced album is one of his finest works.

At the point of producing Diamond Dogs, the musical chameleon and art-rock outsider had disbanded the band Spiders from Mars and was at a crossroads. His plans for a musical based on the Ziggy character and TV adaptation of George Orwell’s "1984" both fell through. In a place of uncertainty and disenchantment, Bowie creates a new persona: Halloween Jack. The record is lyrically bleak and evokes hopelessness. It marks the final chapter in his glam-rock period — "Rebel Rebel" is the swaggering single that hints at the coming punk-rock movement.

Bob Marley - Natty Dread

Bob Marley’s album "Natty Dread," released first in Jamaica in October 1974 later globally in 1975, marked his first record without his Rastafari brethren in song Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer. It also introduced the back-up vocal stylings of the I Threes (Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths.)

The poet and the prophet Marley waxes on spiritual themes with songs like "So Jah Seh/Natty Dread'' and political commentary with tracks,"Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)" and "Rebel Music (3 O’clock Road Block)." The album also Includes one of the reggae legend’s best-loved songs, the ballad "No Woman No Cry," which paints a picture of "government yards in Trenchtown" where Marley’s feet are his "only carriage."

Queen - Sheer Heart Attack

The third studio album released by the British rockers, Queen, is a killer. The first single, "Killer Queen," reached No. 2 on the British charts — and was the band’s first U.S. charting single. The record also peaked at No.12 in the U.S. Billboard albums charts.

This record shows the four-time GRAMMY nominees evolving and shifting from progressive to glam rock. The album features one of the most legendary guitar solos and riffs in modern rock by Brian May on "Brighton Rock." Clocking in at three minutes, the noodling showcases the musician’s talent via his use of multi-tracking and delays to great effect.

Randy Newman - Good Old Boys

Most recognize seven-time GRAMMY winner Randy Newman for his work on Hollywood blockbuster scores. But, in the decade before composing and scoring movie soundtracks, the songwriter wrote and recorded several albums. Good Old Boys was Newman’s fourth studio effort and his first commercial breakthrough, peaking at No. 36 on the Billboard charts.

The concept record, rich in sarcasm and wit, requires a focused listen to grasp the nuances of Newman’s savvy political and social commentary. The album relies on a fictitious narrator, Johnny Cutler, to aid the songwriter in exploring themes like "Rednecks" and ingrained generational racism in the South. "Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man)" is as relevant today as when Newman penned it as a direct letter to Richard Nixon. Malcolm Gladwell described this record as "unsettling" and a "perplexing work of music."

Frank Zappa - Apostrophe

Rolling Stone once hailed Frank Zappa’s Apostrophe as "truly a mother of an album." The album cover itself, featuring Zappa’s portrait, seems to challenge listeners to delve into his eccentric musical universe. Apostrophe was the sixth solo album and the 19th record of the musician’s prolific career. The album showcases Zappa’s tight and talented band, his trademark absurdist humor and what Hunter S. Thompson described as "bad craziness."

Apostrophe was the biggest commercial success of Zappa’s career. The record peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard Top 200. The A-side leads off with a four-part suite of songs that begins with "Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow" and ends with "Father Oblivion," a tale of an Eskimo named Nanook. The track "Uncle Remus," tackles systemic racism in the U.S. with dripping irony. In less than three minutes, Zappa captures what many politicians can’t even begin to explain. Musically, Apostrophe is rich in riffs from the two-time GRAMMY winner that showcases his exceptional guitar skills in the title track that features nearly six minutes of noodling.

Gram Parsons - Grievous Angel

Grievous Angel can be summed up in one word: haunting. Recorded in 1973 during substance-fueled summer sessions in Hollywood, the album was released posthumously after Gram Parsons died of a drug overdose at 26. Grievous Angel featured only two new songs that Parsons’ penned hastily in the studio "In My Hour of Darkness" and "Return of the Grievous Angel."

This final work by the cosmic cowboy comprises nine songs that have since come to define Parson’s short-lived legacy to the Americana canon. The angelic voice of Emmylou Harris looms large — the 13-time GRAMMY winner sings harmony and backup vocals throughout. Other guests include: guitarists James Burton and Bernie Leadon, along with Linda Ronstadt’s vocals on "In My Hour of Darkness."

Neil Young - On The Beach

On the Beach, along with Tonight’s the Night (recorded in 1973, but not released until 1975) rank as Neil Young’s darkest records. Gone are the sunny sounds of Harvest, replaced with the singer/songwriter’s bleak and mellow meditations on being alone and alienated.

"Ambulance Blues" is the centerpiece. The nine-minute track takes listeners on a journey back to Young’s "old folkie days" when the "Riverboat was rockin’ in the rain '' referencing lament and pining for time and things lost. The heaviness and gloom are palpable throughout the album, with the beach serving as an extended metaphor for Young’s malaise.

Dolly Parton - Jolene

Imagine writing not just one, but two iconic classics in the same day. That’s exactly what Dolly Parton did with two tracks featured on this album. The first is the titular song, "Jolene," recorded at RCA Studio B in Nashville. The song has been covered by more than a dozen artists.

Released as the first single the previous fall, "Jolene," rocketed to No.1 on the U.S. country charts and garnered the 10-time GRAMMY winner her first Top 10 in the U.K. The song was nominated for a GRAMMY in 1975 and again in 1976 for Best Country Vocal Performance. However, it didn’t take home the golden gramophone until 2017, when a cover by the Pentatonix featuring Parton won a GRAMMY for Best Country Duo/Group Performance.

Also included on this album is "I Will Always Love You," a song that Whitney Houston famously covered in 1992 for the soundtrack of the romantic thriller, The Bodyguard, earning Parton significant royalties.

Barry White - Can’t Get Enough

The distinctive bass-baritone of two-time GRAMMY winner Barry White, is unmistakable. The singer/songwriter's sensual, deep vocal delivery is as loved today as it was then. On this record, White is backed by the 40-member strong Love Unlimited Orchestra, one of the best-selling artists of all-time.

White wrote "Can’t Get Enough of Your Love, Babe," about his wife during a sleepless night. This song is still played everywhere — from bedrooms to bar rooms, even 50 years on. In the U.S., the record hit the top of the R&B pop charts and No.1 on the Billboard 200. Although the album features only seven songs, two of them, including "You’re the First, the Last, My Everything" reached the top spot on the R&B charts.

Lord Shorty - Endless Vibrations

Lord Shorty, born Garfield Blackman, is considered the godfather and inventor of soca music. This Trindadian musician revolutionized his nation’s Calypso rhythms, creating a vibrant up-tempo style that became synonymous with their world-renowned Carnival.

Fusing Indian percussion instrumentation with well-established African calypso rhythms, Lord Shorty created what he originally dubbed "sokah," meaning, "calypso soul." The term soca, as it’s known today, emerged because of a journalist’s altered writing of the word, which stuck. The success of this crossover hit made waves across North America and made the island vibrations more accessible outside the island nation.

Artists Who Are Going On Tour In 2024: The Rolling Stones, Drake, Olivia Rodrigo & More