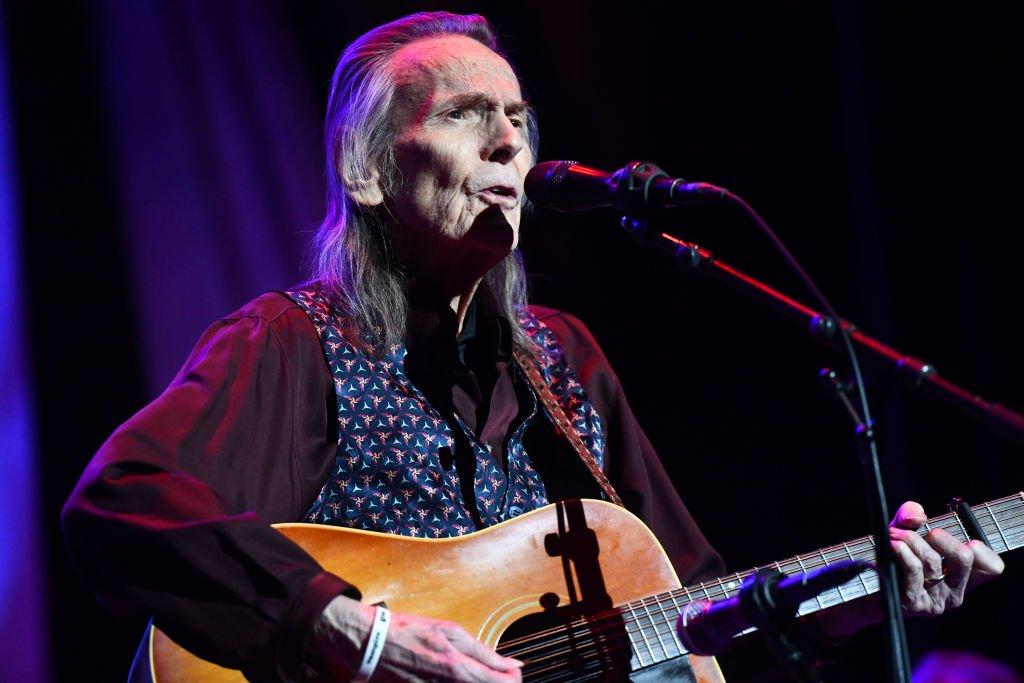

Photo: Scott Dudelson/Getty Images

list

Remembering Gordon Lightfoot: 5 Essential Songs From The Prolific Canadian Songwriter

Gordon Lightfoot passed away on May 1 at age 84; his influence and impact have been felt worldwide.The four-time GRAMMY nominee wrote over 500 songs, here are five of his most enduring.

Bob Dylan, not one to give compliments lightly, was one of Gordon Lightfoot’s biggest fans.

"I can’t think of any Gordon Lightfoot song I don’t like," he once said. "Every time I hear a song of his, it’s like I wish it would last forever."

Canadian songwriter Gordon Lightfoot possessed a rare talent to craft the right turn of phrase and pen timeless songs. In a career spanning more than six decades, Lightfoot wrote lingering melodies with carefully chosen words that spoke to generation after generation. He could capture the zeitgeist just as easily as he could write a lasting love song or universal story. He loved to paint pictures of his native land in his compositions.

On Monday, the legendary songwriter passed away at 84 years old. He leaves behind a catalog of more than 500 songs and 20 studio albums.

"Gordon Lightfoot captured our country’s spirit in his music — and in doing so, he helped shape Canada’s soundscape. May his music continue to inspire future generations, and may his legacy live on forever," Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted.

Lightfoot's fans include fellow prolific songwriter Neil Young, who called him "a Canadian legend." On his website, Young described Lightfoot as "a songwriter without parallel" whose "melodies and words were an inspiration to all writers who listened to his music, as they will continue to be through the ages. There is a unique and wonderful feeling to Gordon's music."

Susan Stewart, Managing Director of the Recording Academy's Songwriters & Composers Wing, described the four-time GRAMMY nominee as "one of the best songwriters in the world.

"I once had the pleasure of producing a show where he performed. If at first he came off as a bit shy, he emerged as extremely kind and intentional. He told us that he thought of himself as an entertainer, but after being in Nashville, he was proud to be reminded that he was a songwriter," she says. "Gordon’s songs were so vulnerable and honest, and he could weave stories in his lyrics that fired the imagination. Truly one of a kind."

Born in 1938 in Orillia, Ontario (birthplace of the Mariposa Folk Festival) Lightfoot’s career began in the 1960s coffeehouse folk club circuit. As singer/songwriter, Lightfoot first honed his sound and workshopped his songs in Toronto’s Yorkville neighborhood, later working in New York City’s Greenwich Village. His debut album, Lightfoot!, arrived in 1966.

The following list easily could be five times as long, but here are five essential Gordon Lightfoot songs that showcase his gifts.

"Early Morning Rain" (1966)

Written in 1964, but not released until 1966 on the album of the same name, "Early Morning Rain" is one of Lightfoot’s most poetic and poignant songs. With lines like "this old airport’s got me down/ it’s no earthly good to me/ And I’m stuck here on the ground as cold and drunk as I can be," the song evokes a feeling of loneliness and homesickness.

It is one songwriters continually return to as a masterclass in what makes a great song. Judy Collins, Ian & Sylvia and Peter, Paul & Mary all covered this classic. Bob Dylan took his turn at this song in 1970; Lightfoot admitted this was a huge boost to his career as it validated him to a whole new audience that looked to Dylan as the bar when it came to songwriters.

"Canadian Railroad Trilogy" (1967)

Canada’s national public broadcaster (The CBC) originally commissioned Lightfoot to write this song to mark the country’s centennial celebrations in 1967. It appeared on The Way I Feel, Lightfoot's second studio album.

Written in just three days, the composition tells the story of the laborers who built Canada’s national railroad, which connected the country from coast to coast. The tempo mimics a train rolling down the tracks. John Mellencamp and George Hamilton IV, among many others, have covered this storied song.

"If You Could Read My Mind" (1969)

Recorded in Los Angeles for the album Sit Down Young Stranger — his first record for Warner’s Reprise label — this ballad earned the Canadian folk singer his second GRAMMY nomination.

The wistful song was the artist’s first No.1 hit in the U.S., helped him achieve his first gold record, and was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003.

A rumination on his divorce, "If You Could Read My Mind" describes feelings that resonate with anyone who has ever experienced heartache with a pensive melody to match. One of Lightfoot’s most covered songs — Glen Campbell and Olivia Newton-John have offered versions, in addition to unique takes from jazzman Herb Albert and Stars on 54, who turned the track into a disco and pop hit in the late '90s.

"Sundown" (1974)

Released in 1974 as a single from the album of the same name, "Sundown" is another of Lightfoot’s songs about a complicated relationship. With its dark lyrics and brooding and bluesy melody, this hit chronicles his tumultuous affair with Cathy Smith, who later was charged in the accidental death of actor John Belushi.

The song reached No. 1 on both the Canadian and U.S. Billboard Hot 100. In 2023, Depeche Mode performed a unique cover of this timeless classic with the BBC Concert orchestra.

"The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" (1976)

Released in June 1976 on Summertime Dream, the song peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard charts. It was nominated for a pair of GRAMMY Awards — Song Of The Year and Best Pop Vocal Performance.

"The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" showcases the artist’s ability to share a moment in history in song. It’s no wonder it is one of Lightfoot’s most beloved and enduring songs. The song tells the mariner’s tale of the Great Lakes iron ore freighter (the S.S. Edmound Fitzgerald) that mysteriously sank in November 1975. All 29 of the crew perished in the lake called "Gitche Gumee." Verse by verse, strum by strum, Lightfoot takes the listener on this journey in song to share this tragic moment.

Remembering Harry Belafonte’s Monumental Legacy: A Life In Music, A Passion For Activism

Photo: Danny Clinch

interview

On 'Weathervanes,' Jason Isbell Accepts His Internal Pressures And Fears

With a revealing HBO documentary in the rearview and his first major acting role onscreen in the fall, Jason Isbell is coming to terms with having a public face. His new album with the 400 Unit, 'Weathervanes,' is the product of that self-realization.

At this stage, a Jason Isbell album isn't just an album; it's a juncture in his ongoing press narrative, another breadcrumb trail as per his personal life.

His first three after he left Drive-By Truckers represent the man in the wilderness; 2013's Southeastern and 2015's Something More Than Free were reflective of his newfound sobriety and marriage to musician Amanda Shires.

The birth of his daughter figured heavily in 2017's GRAMMY-winning The Nashville Sound; that album's "If We Were Vampires," a duet with Shires, stands as Isbell's monument to mortality and won a GRAMMY.

With 2020's Reunions came a splashy New York Times feature about Isbell and Shires' marital struggles, with a lede about a brush with a relapse — suddenly, his ascendance seemed freighted, complicated.

All this begs the question: is having his private life codified and illuminated with each record ever irksome, or frustrating, for Isbell?

"Honestly, I think I appreciate that. I think that serves the ultimate purpose of making art — to document your life, because it is really a way of holding on to these things," he tells GRAMMY.com. "If you leave those things behind, they'll sneak up on you, and then you'll find yourself in a bad place, and you won't know why."

Isbell's new album, Weathervanes, is out June 9; it's his sixth with long-running backing band the 400 Unit. At its essence is a psychologically splintered cast of characters, found on highlights like "Death Wish," "King of Oklahoma" and "This Ain't It."

"They're fallible and they're human. And I think they're all trying to do their best in one way or another," Isbell says of the ties that bind them. "There's a lot of me that's in each of them — some moreso than others."

Rather than commenting on his marriage or sobriety, Weathervanes is the product of his changed relationship with pressure, and being in the public eye. The album arrives in the wake of Running With Our Eyes Closed, a raw-nerved HBO documentary about Isbell. He just acted in his first major film, in Martin Scorcese's Killers of the Flower Moon, headed to theaters in October.

"It's OK to say, 'This is a scary thing to do. I'm afraid that people aren't going to connect with it in the same way, and my work is not going to have the same impact on folks that it's had in the past,'" Isbell says. "And once I learned how to admit that to myself and the people that I care about, things got a lot easier."

Read on for an in-depth interview with Isbell about the road to Weathervanes, how being directed by Scorcese informed his process in the studio and surviving his hard-partying, hard-touring Drive-By Truckers days.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Can you draw a thread between where you were at during the Reunions period, and where you're at during the Weathervanes era? The HBO documentary certainly captured the former.

Yeah, yeah. And then, in the middle, we had the lockdown and all that kind of stuff.

For me, the pandemic era — although it's not finished yet, but what we call that pandemic era, that year or two where we were all stuck in the house — was ultimately a good time for me to revisit some psychological, emotional questions that I had for myself, and I sorted a lot of that stuff.

When the bulk of the documentary was made, I was having a hard time dealing with the pressures of my work, and the pressures of family. And the main reason why I was dealing with that was because I just wasn't recognizing it for what it was, and I wasn't aware of the effect that those things were having on me.

Getting stuck in the house with my family and myself for that long, I think, really helped me; it forced me to confront that stuff and admit what it really was that was causing me difficulties. And once I got through that, things opened up and got a lot easier for me.

I had a really, really good time making Weathervanes. I don't know if I had a good time writing it, because I don't know if that's ever exactly fun. It's fun when you finish a song; it feels like you just left the gym.

But when you're sitting down in front of the blank page, it feels like you're walking into the gym, and you might have just gotten four hours of sleep the night before.

What were you dealing with internally? Just childhood stuff, stuff bugging you from the past?

There was some of that. It was also just relationship difficulties; they were just constant.

Amanda and I have been married for 10 years, and it's the kind of thing where you get in this rhythm of life where you go through the same sort of rituals every day, and you ask the same questions and you get the same answers, and it's easy to get into that monotony and not really reach and look for ways to grow.

I think before the pandemic happened, I'd gotten to a point where I was in this rhythm: go out and play shows, make records, come home, spend time with the family. I was sort of ignoring the pressure of all that, and especially in the work.

I've been very fortunate with my last few albums that they were well-received and things have gone really well. And when I go into the studio to make a record… it was hard for me to admit to myself that that caused me anxiety and a lot of stress, because I didn't like how it made me look. I wanted to look tough and look like I had everything under control.

And after making Reunions, I realized that that's not necessarily the case. And once I learned how to admit that to myself and the people that I care about, things got a lot easier.

What psychological or spiritual wells were you drawing from for these songs?

I try to make these characters, and then I follow them around. And I don't know exactly what they're going to do next. I think that's the only way to keep it really natural.

There's a lot of me that's in each of them — some moreso than others. Some of the songs I write, I am writing about me.

But one of the things that I like about songwriting is that you don't really categorize music in that way. You categorize movies and books in that way; there's fiction and nonfiction, there's documentaries and other movies. But for songs, it's all of the above.

So, a lot of this is me, and a lot of it is synthesized characters that have characteristics of multiple people that I know. Then, I just let them act naturally and follow them around, and the themes find there way in there.

I don't have to insert the themes, because there's enough in my unconscious mind that the songs will wind up dealing with real things — as long as I'm honest with everybody.

There's a wide variety of perspectives and experiences in these songs. What do the Weathervanes characters have in common?

I think when it's done right, they have the same things in common that the listeners have. They're fallible and they're human. And I think they're all trying to do their best in one way or another.

That's maybe what I'm exploring more than anything else — not as a mission statement, but a connector, in hindsight, is this idea that people have different circumstances, influences and pressures exerted on them. But what does it mean to try to keep hope, and survive, and do your best in all these different stations of life?

I'm a Randy Newman fanatic; he can dispense a novel's worth of detail in just a few lines, by implying so much negative space. I've noticed you've written in character from the beginning, like him.

When I met Randy at Newport [Folk Festival], I told him the thing about how much I loved his work and everything, and he leaned in really close where nobody could hear and whispered in my ear, "I like your songs, too." That was a huge, huge moment for me. I said, "Well, you don't strike me as much of a bulls—er, so I'm going to take that."

**One of your guiding lights for Reunions' sound was the '80s rock you enjoyed as a kid. What was the aural aesthetic for Weathervanes? And can you talk about the learning curve of self-production?**

I started thinking, OK, here's how these records by Dire Straits and the Police sounded, and this is why they sounded that way, and this is what worked about that, and what translates to now and what doesn't, and what can be replicated and what can't.

So, I brought some of that with me into the Weathervanes recording. Most obviously, on a song like "Save the World," there was an intention I had before I went in the studio. This happens to me a lot. I'll get a big idea, and I'll think, Oh, this is great. We can do the whole record this way.

And by the time I'm in the studio, I'll think, OK, maybe we just use this as a tool. We don't do the entire record like this. Because then, that would take over the concept and distract from everything else.

At first, I wanted to make a dry record. I was listening to [1978's] Outlandos [d'Amour], the Police record, and there's hardly any room or reverb or anything. "Roxanne" — all those songs are right in your ear. And that's a flex, because to do that, you have to be able to sing and play with great tuning and great timing.

And the Police — first of all, there's just three of them, so it's easier to do than it is with five or six people. But they also were master musicians, and you have to be really on point to make a dry record like that, or it's going to be a mess when you go to sing the harmony.

That was something that I wound up using as a tool. I think a lot of this record has less reverb and less room on it than you would expect. I think it was done in a way where you don't necessarily notice it off the bat.

Also, watching the Get Back documentary, I thought, Man, these guys didn't have tuners. They just tuned it by ear for the whole record.

I didn't want to torture my guitar techs, so I wasn't going to make a whole record without any tuners. But there are some moments on this record where we tuned by ear rather than tuning to a machine, so it would sound more human. Really, a lot of my production style — if there is such a thing — is how do we get a little dose of humanity of something that is sort of slick and polished.

I interviewed [Drive-By Truckers co-leader] Patterson [Hood] on Zoom last year, and I was struck at how sweet and energetic he was. How did you guys walk away from those hard-touring years alive and intact?

We don't know the answer to that. We got very lucky. Also, we were white and we were male, and I think that plays a lot pinto it. I think if we had not been white, some cop would've shot us all a long time ago.

I don't know if there was some kind of divine intervention in some of those situations, but I still look back on it and think, I don't know how we survived all that. I really don't.

Were there any near-death experiences?

Oh, there were so many. We saw huge, disastrous accidents happen right in front of us. There were times when we'd be on snowy mountain passes and lose control of the van for 20 seconds, and then finally it would snap back into place. I don't know how it happened.

On a different note, you touched on gun violence in "Save the World." I was struck by how un-preachy it was. I felt like I was in your head, or privy to a family meeting.

That's the trick, you know? You have to be really personal with it, I think.

If you're writing a song about a big, heavy topic like that, don't try to ascend somebody else's perspective. Love, romance, breakups, heartbreak, death; we all have experiences with those things.

So, if that's what you're writing about, you're free to take other perspectives other than your own, because we all have that commonality. We know what those things feel like, or what the fear of those things feels like.

But when you're writing about something like school shootings: I have not been involved in one of those. I've not seen one of those go down firsthand. I've been close a couple of times, but it's not something that I could write from the perspective of somebody who was actually in the building.

So to be honest with the work, what I have to do is think: How does this affect me? How do I feel about this? And then write from that perspective. I don't think anybody's ever noticed this, but the songs where I'm tackling the biggest, most complicated issues are the ones where I'm writing from the most personal point.

**Give me your personal MVP moments from the members of the 400 Unit on Weathervanes.**

[Guitarist] Sadler [Vaden] has this old Vox guitar that has built-in fuzz effects, and he played on that on "Miles," the last song on the album, and really added something special to that.

It's a vintage guitar, but not a highly collectible, very expensive guitar. It's got this weird kind of freak-out fuzz tone that is included in the instrument, and he used that on that song to great success.

Jimbo [Hart]'s bass on "Middle of the Morning" is just a beautiful groove. It's a simple part, but the timing of it it is just exactly right. He's just right in the pocket.

Chad [Gamble], on the outro to Miles, where there's multiple drum kits happening — I think he handled that beautifully, and built up to that big cymbal crash at the end.

We wanted a gong, but Blackbird [Studio in Nashville] didn't have a gong. They had this crash cymbal that was 72 inches or something; it was huge. It took up the whole reverb chamber. When Chad made the big crash at the end, we were all jumping up and screaming in the control room when it happened because it was so f—ing hilarious.

Derry [deBorja] — I feel like his synthesizer part on "Save the World" was a big moment for him. He spent a lot of time on that. We tried to send the clock from the Pro Tools session to the analog synthesizer and get it to line up.

It proved to be a very complicated exercise, because we were trying to marry new technology and old technology, but he found a way to make it work.

Let's end this with a lightning round. I polled my Facebook friends on what they'd want to ask you; it's a mix of New York music industry people and hometown friends from California.

This one's from Ryan Walsh, who leads a rock band called Hallelujah the Hills. He asks if when "white nationalist monsters" figure out your politics and tell you on Twitter they won't listen to you again, "do they really abandon ship, or is even that promise nothing but some sad barkin'?"

I don't think most of those were ever fans to begin with. I refuse to believe that those people have been actually listening to my songs all along. I think they see something that somebody's retweeted, and then they Google me and they see that I'm a musician, and they say, "I was your fan until just now." I think it's all just a b—shit tactic.

The jazz-adjacent singer/songwriter Dara Tucker says, "I'd like to hear his thoughts on Gordon Lightfoot."

Oh, Gordon was amazing. I played a song that I wrote, "Live Oak," last week, after Gordon's passing. I mentioned from the stage that I don't think I could have written that song without Gordon's work. The way he dealt with place, and the way he made folk music very specific to his own life.

I think "Carefree Highway" was the first song where I had that kind of lightbulb moment, where I thought, Oh, he's feeling really bad about something. This is not a celebration. This is not hippy-dippy s—. This is somebody saying, "I'm sorry." And that was a big moment for me.

Journalist Tom Courtenay asks, "Does he think Nashville/radio's gatekeeping is fixable, or does it only make sense for anyone remotely subversive to work outside of it at this point?"

I think what, if anything, will fix it, is when this particular brand of straight white male country music is no longer as popular as it is.

I don't think that's a good thing. I would love to see it fixed from the inside. But the way I picture the state of popular country music right now is they're staring at a machine with a whole bunch of buttons, and there's one button that they know will spit out money when they hit it, so they just keep hitting it.

They won't take their hand off of it long enough to try any of the other buttons, even though some of the other buttons might spit out more money.

Singer/songwriter Ephraim Sommers asks, "What is his greatest difficulty, obstacle or weakness as a songwriter, and how has he worked to overcome it?"

Humor is hard. It's hard because I laugh a lot in my everyday life, and it's hard to find a way to work humor into a song. The way that I work to overcome it is just by trying to notice different situational details that would create a funny image in a song.

It's something I'm not very good at. John Prine was great at it; Todd Snider's great at it. But to be funny without being bitter in the kind of songs that i write is a real challenge.

I don't want it to be funny in a self-referential way. I would like for it to be funny no matter who was saying it or writing it. That's a tough one for me, but I just keep trying over and over and over, until finally the joke is present enough for somebody to get it.

I'll close with my own question: What's grist for the mill creatively for you right now? What are you listening to, reading or watching?

Jennifer Egan, The Candy House; I'm reading that right now. Last night, we watched Guy Ritchie's The Covenant, the war movie. That was good. Of course, I like "Succession."

Right now, I'm just super excited about the Scorcese movie that I was in. I heard rumors that the trailer's coming out tomorrow.

Tell me about that.

That process of working on that movie really found its way into the studio when I went back to record — just the way Scorcese was able to hear other people's opinions and collaborate while still keeping his vision.

Actors are people — they're not instruments — so you can't completely manipulate them, no matter how good you are at directing. So, it's not like the director is the guitar player and the actor is the guitar. There are a bunch of real humans in the room, so they're all going to have opinions and ways of delivering things.

To see him navigate that and hear everything — and still make the movie that he saw in his mind — was a pretty incredible thing for me.

Drive-By Truckers' Patterson Hood On Subconscious Writing, Weathering Rough Seasons & Their New Album Welcome 2 Club XIII

news

Gordon Lightfoot Visits The GRAMMY Museum

GRAMMY-nominated folk/rock legend performs and discusses his 1976 hit "The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald"

GRAMMY-nominated folk/rock legend Gordon Lightfoot recently participated in an installment of the GRAMMY Museum's An Evening With series. Before an intimate audience at the Museum's Clive Davis Theater, Lightfoot discussed his early music education and his 1976 hit "The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald," among other topics. Lightfoot also performed a brief set, including "The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald" and his 1974 hit "Sundown."

"['The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald'] — it's a whole story unto itself, from start to finish, and it still goes on [to] this day," said Lightfoot.

Regarded as one of Canada's leading singer/songwriters, Lightfoot first gained acclaim in the 1960s penning hits for artists such as Peter, Paul And Mary and Marty Robbins. After signing with United Artists Records in 1966, Lightfoot released his debut album, Lightfoot! He followed with two classic albums, 1967's The Way I Feel and 1968's Did She Mention My Name? — the latter earned him his first career GRAMMY nomination for Best Folk Performance. He scored his first platinum and lone No. 1 album to date with 1974's Sundown, which featured the chart-topping title track and Top 10 hit "Carefree Highway." Cold On The Shoulder was released in 1975 and reached No. 10, followed by the platinum-selling Summertime Dream (1976, No. 12). Considered one of Lightfoot's finest albums, Summertime Dream featured "The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald," a ballad about the final hours of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in Lake Superior in 1975. The song garnered Lightfoot two GRAMMY nominations, including Song Of The Year, at the 19th Annual GRAMMY Awards.

In 1986 Lightfoot was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. That same year he released East Of Midnight, followed by Waiting For You (1993), A Painter Passing Through (1998) and Harmony (2004). Lightfoot's most recent album, 2012's All Live, features a collection of his greatest hits performed at Toronto's famed Massey Hall. Also in 2012, Lightfoot was inducted into the Songwriters Hall Of Fame.

Lightfoot is currently in the midst of a U.S. tour, with dates scheduled through November.

Upcoming GRAMMY Museum events include Reel To Reel: Greenwich Village: Music That Defined A Generation (June 24).

news

Songwriters Hall Inducts 2012 Class, Polaris Prize Nominees Announced

Songwriters Hall Inducts 2012 Class, Polaris Prize Nominees Announced

GRAMMY nominee Gordon Lightfoot, GRAMMY-nominated songwriting duo Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt, and GRAMMY winners Don Schlitz, Bob Seger and Jim Steinman were inducted into the 2012 Songwriters Hall of Fame at the 43rd Annual Induction and Awards Dinner on June 14 in New York. GRAMMY winners Bette Midler and Ne-Yo were honored with the Sammy Cahn Lifetime Achievement Award and Hal David Starlight Award, respectively. In other awards news, nominees for the 2012 Polaris Music Prize were announced with GRAMMY winner Leonard Cohen and GRAMMY nominees Drake and Feist making the list of 40 nominees for Old Ideas, Take Care and Metals, respectively, among others. The honor recognizes the best Canadian album of the past year across all genres and includes a cash award of $30,000. The winner will be revealed on Sept. 24 in Toronto. (6/15)

Beach Boys Break Billboard 200 Record

The Beach Boys' That's Why God Made The Radio debuted at No. 3 on the Billboard 200, marking the second-longest span between Top 10 albums: 49 years and one week. The tally surpasses the Beatles, whose stretch of Top 10 albums covers 47 years, seven months and three weeks, according to Billboard.biz. The Beach Boys first appeared in the Top 10 in 1963 with Surfin' U.S.A. GRAMMY winner Frank Sinatra leads with the longest Top 10 albums span on the Billboard 200 at 52 years, two months and one week. (6/15)

news

"GRAMMY Effect" Drives Album Sales

"GRAMMY Effect" Drives Album Sales

Following earlier reports, the 54th Annual GRAMMY Awards helped drive album sales this week for several GRAMMY performers, including Adele, who's GRAMMY-winning Album Of The Year 21 holds the No. 1 spot on the Billboard 200 for the 21st consecutive week with sales of 730,000 units, up 207 percent, according to a Billboard report. The 2012 GRAMMY Nominees album jumped to No. 5 with 85,000 units sold, a 66 percent increase. Other GRAMMY performers and winners experiencing sales increases include the Civil Wars (up 178 percent), Foo Fighters (up 134 percent), Bruno Mars (up 133 percent), Bon Iver (up 61 percent), Taylor Swift (up 60 percent), Lady Antebellum (up 47 percent), Coldplay (up 26 percent), Skrillex (up 23 percent), and the Band Perry (up 22 percent). Overall album sales this week totaled 7.7 million units, up 13 percent from last week, and up 7 percent compared to the same point in 2011. (2/22)

Adele Among Brit Awards 2012 Winners

GRAMMY winner Adele was among the top winners at the Brit Awards 2012 on Feb. 21 in London, taking home awards for British Female Solo Artist and British Album of the Year for 21. Other artists garnering awards were Coldplay, Lana Del Rey, Foo Fighters, Bruno Mars, Rihanna, and British singer/songwriter Ed Sheeran, and GRAMMY-nominated alternative rock band Blur were honored with the Outstanding Contribution to Music award. In related news, GRAMMY nominees Gordon Lightfoot and musical-writing duo Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt; and GRAMMY winners Jim Steinman, Bob Seger and Don Schlitz will be inducted into the 2012 Songwriters Hall of Fame at the 43rd Annual Induction and Awards Dinner on June 14 in New York. (2/22)