Photo: Miikka Skaffari/FilmMagic/Getty Images

Karnig Manoukian of Charming Liars

news

Charming Liars Drop Must-Hear Cover Of Post Malone's "Circles" To Benefit Disaster Relief In Lebanon

With co-signs from the likes of Elton John and System Of A Down's Serj Tankian, the single is raising money for disaster relief efforts following the Aug. 4 explosion in Beirut

Los Angeles alternative outfit Charming Liars have released a brand new benefit single. The song: a soaring cover of one of their favorite Post Malone songs, "Cirlcles." The cause: to raise funds for disaster relief efforts following the devastating Aug. 4 explosion in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. Have a listen:

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//o4tVfKjcW-o' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Charming Liar's version of the Posty hit has received support on social media from the likes of Elton John and Serj Tankian of System Of A Down.

Originally formed in London's West End by guitarist/producer Karnig Manoukian and bassist Mike Kruger, Charming Liars relocated to Los Angeles in 2013 where they linked up with vocalist Kiliyan Maguire. The band explained the affect of the disaster in a heartfelt post accompanying the new single:

“On August 4th, the third-largest explosion in our world history occurred in Beirut, Lebanon resulting in a devastating amount of destruction, damage, and death to the country and people of Lebanon. Karnig, who is Lebanese Armenian, and all of us Charming Liars, want to do our part to help rebuild and restore the beautiful city of Beirut as well as provide aid to the estimated 300,000 Lebanese who have been left homeless as a result of this tragic event.”

Proceeds from the single will go several organizatons to aid their disaster relief efforts, including the Lebanese Red Cross, Impact Lebanon, Saint George Hospital Beirut, and others.

"Please download, stream, and share it on all music platforms to help us raise funds for an incredible cause," the band added. "Thank you for your continuous support and see you soon!”

Beatport Announces 'Together For Beirut' Reconnect Livestream

Photo: Matt Winkelmeyer

list

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Ice Spice, Ariana Grande, Post Malone, Coldplay & More

As we slip into summer, get the season started by listening to these new songs, albums and collaborations from Gracie Abrams, Kygo, The Joy and more that dropped on June 21.

The first New Music Friday of the summer delivers us fresh jams packed with exciting collaborations and debuts.

This week features releases from big name, genre-crossing collaborations, including Ariana Grande's remix of "the boy is mine" with Brandy and Monica, and Post Malone teaming up with Blake Shelton on their new track "Pour Me a Drink." As you build your new summer playlist, make sure you don't miss out on these ten must-hear tunes.

Ice Spice — "Phat Butt"

After a massive year with the release of her EP Like..? and four nominations at the 2024 GRAMMYs, Ice Spice is ready to level up once again with her newest single, "Phat Butt." With self-assured lyricism on top of a classic drill beat that is true to her sound, the track serves as the second single to be released from her debut album, Y2K!. "Phat Butt" comes as both a message to those who lacked belief in Ice Spice’s music career, but also as a quintessential summer anthem.

In the self-directed music video, the rapper is shown performing in front of a wall of graffiti with grainy video filters, emphasizing the Y2K feel. Ice Spice is set to take on her Y2K World Tour next month and it's no doubt that this "Phat Butt" will be a highlight on her setlist.

Explore More: The Rise Of Ice Spice: How The "Barbie World" Rapper Turned Viral Moments Into A Full-On Franchise

Ariana Grande, Brandy, & Monica — "the boy is mine (remix)"

When asking different groups who sings the song "the boy is mine," you're likely to get two answers. Some will say pop star Ariana Grande, while others will think of the original 1998 R&B hit by Brandy and Monica, which won the GRAMMY for Best R&B Performance By A Duo Or Group With Vocal in 1999. Doubling down on the shared name of the track and bridging the generational gap among music lovers, Grande, Brandy, and Monica have come together for a fresh remix of "the boy is mine," and the internet couldn't be more ecstatic.

"My deepest and sincerest thank you to Brandy and Monica, not only for joining me for this moment, but for your generosity, your kindness, and for the countless ways in which you have inspired me," said Grande in an Instagram post announcing the collaboration. "This is in celebration of you both and the impact that you have had on every vocalist, vocal producer, musician, artist that is creating today."

Read More: 5 Takeaways From Ariana Grande's New Album Eternal Sunshine

Post Malone & Blake Shelton — "Pour Me a Drink"

Post Malone has been dipping his toes into the country genre for some time now and fans have been anxiously awaiting his promised western era post Cowboy Carter.

Malone and Shelton first ignited excitement with a sneak peek of their song, "Pour Me a Drink" at the CMA Fest earlier this month. Since Posty announced the official release on Instagram, fans have eagerly awaited its arrival on streaming services. The track serves as a tantalizing preview of Post Malone's upcoming country album, F-1 Trillion, coming August 16.

Read More: Post Malone's Country Roots: 8 Key Moments In Covers and Collaborations

Coldplay — "feelslikeimfallinginlove"

Coldplay has been generating excitement as they embark on their next chapter, with the release of their latest single, "feelslikeimfallinginlove." Over the past few weeks, they've been feeding fans with sneak peeks on social media and performing the song live on their world tour.

The track sets the stage for the release of Coldplay's highly anticipated tenth studio album, Moon Music, set to land in early October. True to their brand, this song is geared to uplift your spirits, making it the perfect anthem for carefree summer car rides with the windows down.

Read More: How Coldplay's Parachutes Ushered In A New Wave Of Mild-Mannered Guitar Bands

Kygo — 'Kygo'

Ten years into his career, Norwegian DJ Kygo is dropping his self-titled album, Kygo, which he teased last week with the single "Me Before You" featuring Plested. The song, backed by a thumping mid-tempo instrumental, vividly narrates the transformative experience of being deeply influenced by someone in a relationship and not wanting to return to who you were before. The 18-track project features diverse and vibrant collaborations with unexpected guests like the Jonas Brothers and Ava Max.

Maren Morris & Julia Michaels — "cut!"

Maren Morris and Julia Michaels, GRAMMY-winners both independently renowned for their iconic music collaborations, are now joining forces to release their electrifying new track, "cut!" The duo has been working together for a few years, with Michaels' co-writing Morris' "Circles Around Town," which received a nomination for Best Country Song at the 2023 GRAMMYs. So, while this collaboration might not come as a surprise, it is still certainly a welcomed one.

After a two-year hiatus from releasing music, pop enthusiasts have been eagerly anticipating Morris' return to the spotlight. "Can't wait to cathartically scream f*ck at the top of our lungs together," Morris said in an Instagram post announcing the track.

Learn More: Behind Julia Michaels' Hits: From Working With Britney & Bieber To Writing For Wish

Gracie Abrams — 'The Secret of Us'

Building on the success of her debut album, Good Riddance, and the skyrocketing momentum of her career after opening The Eras Tour, California-native Gracie Abrams has unveiled her much-anticipated sophomore album, The Secret of Us.

The album includes the track, "Close to You," which was released ahead of the album drop as the full realization of a 20-second snippet that Abrams posted on Instagram back in 2018. After sitting on the track for six years and relentless pleas from fans, the pop artist finally delivered the full song — a mesmerizing blend of Abrams’ vocal prowess and heartfelt lyricism.

Learn More: How Making Good Riddance Helped Gracie Abrams Surrender To Change And Lean Into The Present

6LACK — "F**k The Rap Game"

6LACK is rebranding himself and making sure everyone knows. The release of his newest track, "F**k The Rap Game" addresses the phenomenon of getting caught up in the glitz and glamor of the entertainment business, tying in the importance of staying true to one's roots. The Atlanta-raised artist is currently on tour with rapper Russ, with whom he recently released the single "Workin On Me,” another nod to 6LACK's ongoing mission of self-reflection and deep introspection.

“A better me equals a better you equals a better us. That’s been the formula of my life. I can’t thrive unless I’m around people who are constantly trying to better themselves as individuals,” 6LACK said in an interview with GRAMMY.com last year. “It took a second of me really looking at myself in the mirror, being honest and saying: I am not doing as much work on myself as I claim to be doing and want to be doing on myself.”

Read More: 6lack On His Comeback Album SIHAL: "I’m Playing A Different Game"

The Joy — 'The Joy'

Months after their buzzworthy performance with Doja Cat at Coachella, South African quintet The Joy has released their self-titled album through Transgressive Records. The album was recorded live, in real time, at Church Studios in London and features no instruments or overdubs — just pure, raw vocals that capture the group's authentic sound.

The Joy came together through a serendipitous twist of fate. Years back, five boys arrived early to their school choir practice and decided to have an impromptu jam session. Realizing their undeniable musical chemistry, The Joy was born, quickly garnering global acclaim. "They are, like, my favorite group," Jennifer Hudson exclaimed on her talk show.

Surfaces — 'good morning'

Known for their feel-good tunes that took over TikTok in 2019, Surfaces presents their sixth album, Good Morning. In tracks like, “Real Estate,” the band chronicles the idea of exploring one’s mind and thoughts, above all other features, backed by a tropical lo-fi instrumental, as well as a steady thump of a bass, and trilling trumpets.

“’Real Estate’ is about the infatuation with that place in someone’s mind that you can’t get enough of,” Surfaces explained in a press statement. “It’s a familiar place to call home that feels safe and deserves all the love in the world. We wanted to capture the bliss of finding that space and reveling in it.”

Lauren Watkins — 'The Heartbroken Record'

Lauren Watkins has a packed summer schedule, which includes opening for country artist Morgan Wallen and releasing her second studio album, The Heartbroken Record. This project draws inspiration from music industry veterans like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, while also infusing influences from contemporary artists like Kacey Musgraves and Miranda Lambert. Each track from the album underscores stories of love and loss, woven together by the overarching theme of heartbreak.

"I didn't want to just put an album out — I wanted it to be purposeful," Watkins said in a press statement. "It's the past several years of my life, and that was just so much heartbreak and dramatic girl-feelings, but I think in a really deep and relatable way… and it just needs to get off my chest."

Why 2024 Is The Year Women In Country Music Will Finally Have Their Moment

Photos: Dave Benett/Getty Images for Depop; Matthew James-Wilson; Claryn Chong; Burak Cingi/Redferns; Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Boston Calling; Tim Mosenfelder/WireImage; Courtesy Interscope Records

news

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 2024 Pride Month Playlist Of Rising LGBTQIA+ Artists

From Laura Les and Nxdia to Alice Longyu Gao and Bambi Thug, a new class of LGBTQIA+ artists is commanding you to live out loud.

LGBTQ+ artists have long shaped the music industry and culture at large, offering audiences a glimpse into their unique lives, shared experiences and so much more.

Queer artists are foundational to American music; Released in 1935, Lucille Bogan’s “B.D. Woman’s Blues” was one of the first lesbian blues songs — and wouldn’t be the last. Fellow blues singers Gladys Bently, Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith also sang about same-sex love (thinly veiled or otherwise). On opposite ends of the 1970s musical spectrum, disco (itself a queer artform) and punk musicians explored gender identity in song and performance — defying conventional gender norms at the time. Gender fluidity became part of the culture during the '80s, with genre-bending artists such as David Bowie and Boy George leading the charge.

In the decades since, a spectrum of LGBTQIA+ artists is opening up — and creating work about — their sexual and gender identities. Queer artists are also being recognized for their contributions to global culture. In 1999, six-time GRAMMY winner Elton John became the first gay man to receive the GRAMMY Legend Award.

Read more: The Evolution Of The Queer Anthem: From Judy Garland To Lady Gaga & Lil Nas X

The GRAMMY Awards have become more inclusive of the queer community. In 2012, the Music's Biggest Night became the first major awards show to remove gendered categories. In 2014, Queen Latifah officiated a mass wedding of straight and gay couples during Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ “Same Love” performance, which included gay icon Madonna performing her “Open Your Heart.” In 2022, Brazilian singer/songwriter Liniker became the first trans artist to win a Latin GRAMMY. Just three months later, Sam Smith and Kim Petras became the first nonbinary and trans artists, respectively, to win a GRAMMY Award for Best Pop Duo/Group Performances for their collaboration, “Unholy.” The 2024 GRAMMYs marked a record high for queer women winning major awards: Miley Cyrus, Billie Eilish, Victoria Monét, and boygenuis all took home golden gramophones in the Big Six Categories.

As queer artists continue to command attention across genres and get their flowers on the global stage, a new class of LGBTQIA+ artists is emerging into the scene. These artists are both following in the steps of established acts by sharing their experiences through their music, and creating work that is unique to their lives and time.

In celebration of Pride Month 2024, GRAMMY.com has put together a playlist of rising artists across the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, whose sound commands you to live out loud.

PRIDE & Black Music Month: Celebrating LGBTQIA+ & Black Voices

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 2024 Pride Month Playlist Of Rising LGBTQIA+ Artists

9 New Pride Anthems For 2024: Sabrina Carpenter's "Espresso," Chappell Roan's "Casual" & More

What's The Future For Black Artists In Country Music? Breland, Reyna Roberts & More Sound Off

Why Beyoncé Is One Of The Most Influential Women In Music History | Run The World

9 Ways To Support Black Musicians & Creators Year-Round

How Beyoncé Is Honoring Black Music History With 'Cowboy Carter,' "Texas Hold Em," 'Renaissance' & More

The Evolution Of The Queer Anthem: From Judy Garland To Lady Gaga & Lil Nas X

15 LGBTQIA+ Artists Performing At 2024 Summer Festivals

50 Artists Who Changed Rap: Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Nicki Minaj, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem & More

Fight The Power: 11 Powerful Protest Songs Advocating For Racial Justice

How Rihanna Uses Her Superstardom To Champion Diversity | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Beyoncé Has Empowered The Black Community Across Her Music And Art | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Women Essential To Rap: Cardi B, Lil' Kim, MC Lyte, Sylvia Robinson & Tierra Whack

Celebrate 40 Years Of Def Jam With 15 Albums That Show Its Influence & Legacy

Watch Frank Ocean Win Best Urban Contemporary Album At The 2013 GRAMMYs | GRAMMY Rewind

A Brief History Of Black Country Music: 11 Important Tracks From DeFord Bailey, Kane Brown & More

10 Women In African Hip-Hop You Should Know: SGaWD, Nadai Nakai, Sho Madjozi & More

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

The Rise Of The Queer Pop Star In The 2010s

How Sam Smith's 'In The Lonely Hour' Became An LGBTQIA+ Trailblazer

How Queer Country Artists Are Creating Space For Inclusive Stories In The Genre

How Jay-Z Became The Blueprint For Hip-Hop Success | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Kendrick Lamar Became A Rap Icon | Black Sounds Beautiful

Dyana Williams On Why Black Music Month Is Not Just A Celebration, But A Call For Respect

6 LGBTQIA+ Latinx Artists You Need To Know: María Becerra, Blue Rojo & More

7 LGBTQ+ Connections In The Beatles' Story

Breaking Down Normani's Journey To 'Dopamine': How Her Debut Album Showcases Resilience & Star Power

10 Alté Artists To Know: Odunsi (The Engine), TeeZee, Lady Donli & More

Celebrating Black Fashion At The GRAMMYs Throughout The Decades | Black Music Month

FLETCHER Is "F—ing Unhinged" & Proud Of It On 'In Search Of The Antidote'

For Laura Jane Grace, Record Cycles Can Be A 'Hole In My Head' — And She's OK With That

15 Essential Afrorock Songs: From The Funkees To Mdou Moctar

50 Years In, "The Wiz" Remains An Inspiration: How A New Recording Repaves The Yellow Brick Road

Why Macklemore & Ryan Lewis' "Same Love" Was One Of The 2010s' Most Important LGBTQ+ Anthems — And How It's Still Impactful 10 Years On

Songbook: The Complete Guide To The Albums, Visuals & Performances That Made Beyoncé A Cultural Force

Why Cardi B Is A Beacon Of Black Excellence | Black Sounds Beautiful

Queer Christian Artists Keep The Faith: How LGBTQ+ Musicians Are Redefining Praise Music

9 Revolutionary Rap Albums To Know: From Kendrick Lamar, Black Star, EarthGang & More

9 "RuPaul's Drag Race" Queens With Musical Second Acts: From Shea Couleé To Trixie Mattel & Willam

5 Black Artists Rewriting Country Music: Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, Jimmie Allen, Brittney Spencer & Willie Jones

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

How Whitney Houston’s Groundbreaking Legacy Has Endured | Black Sounds Beautiful

LGBTQIA+-Owned Venues To Support Now

Celebrate The Genius Of Prince | Black Sounds Beautiful

Explore The Colorful, Inclusive World Of Sylvester's 'Step II' | For The Record

Black-Owned Music Venues To Support Now

5 Artists Fighting For Social Justice Today: Megan Thee Stallion, Noname, H.E.R., Jay-Z & Alicia Keys

Artists Who Define Afrofuturism In Music: Sun Ra, Flying Lotus, Janelle Monae, Shabaka Hutchings & More

5 Trans & Nonbinary Artists Reshaping Electronic Music: RUI HO, Kìzis, Octo Octa, Tygapaw & Ariel Zetina

From 'Shaft' To 'Waiting To Exhale': 5 Essential Black Film Soundtracks & Their Impact

5 Emerging Artists Pushing Electronic Music Forward: Moore Kismet, TSHA, Doechii & Others

5 Artists Essential to Contemporary Soca: Machel Montano, Patrice Roberts, Voice, Skinny Fabulous, Kes The Band

How Quincy Jones' Record-Setting, Multi-Faceted Career Shaped Black Music On A Global Scale | Black Sounds Beautiful

5 Black Composers Who Transformed Classical Music

Brooke Eden On Advancing LGBTQ+ Visibility In Country Music & Why She's "Got No Choice" But To Be Herself

Let Me Play The Answers: 8 Jazz Artists Honoring Black Geniuses

Women And Gender-Expansive Jazz Musicians Face Constant Indignities. This Mentorship Organization Is Tackling The Problem From All Angles.

Histories: From The Yard To The GRAMMYs, How HBCUs Have Impacted Music

How HBCU Marching Band Aristocrat Of Bands Made History At The 2023 GRAMMYs

Photo: Dave Benett/Getty Images

list

9 Reasons Why 'The Lion King' Is The Defining Disney Soundtrack

Thirty years after 'The Lion King: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack' was released, revisit all the ways it became Disney's ultimate musical moment, from multiple GRAMMYs to a Broadway smash.

Following the untimely death of their regular composer Howard Ashman, who, alongside Alan Menken, had written the soundtracks for The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin, Walt Disney Feature Animation were forced to look elsewhere for 1994's The Lion King. As their first film ever based on an original story, and their first to consist entirely of animal characters, the Mouse House was already taking something of a gamble. And they further refused to play it safe by appointing a pop star with no prior experience of the Hollywood machine.

Luckily, the leftfield choice of British national treasure Elton John (then without his Sir title), proved to be a masterstroke. Alongside Tim Rice, the lyricist best-known for his musical theater work with Andrew Lloyd Webber, the Rocket Man delivered five instant classics. Not only did the likes of "Can You Feel The Love Tonight," "I Just Can't Wait To Be King," and "Circle of Life" perfectly help push forward the narrative, but they also helped push the film to awards glory at the Oscars and GRAMMYs, a colossal box office figure of nearly one billion dollars, and permanent residency in the pop culture landscape.

Of course, John and Rice can't take all the credit for Lion King's roaring success. Acclaimed composer Hans Zimmer also came on board to give an orchestral touch to the Shakespeare-inspired tale of an heir apparent, who after escaping his wicked uncle's clutches, returns years later to reclaim his rightful position. And professional singers Carmen Twillie, Sally Dworsky, and Kristle Edwards joined household names such as Nathan Lane, Whoopi Goldberg, and Rowan Atkinson in the recording booth, further driving the massive impact of the movie and its music.

Thirty years after it first enamored the Blockbuster generation, we take a look at how The Lion King still sits at the top of the Disney soundtrack throne.

It's Still The Biggest Selling Disney Soundtrack

Forget The Jungle Book, Beauty and the Beast, or the more recent musical phenomenon that is Frozen. When it comes to pure sales, the runaway Disney soundtrack leader is The Lion King. The Rice/John/Zimmer collaboration shifted nearly five million copies domestically in 1994 alone. And its impressive worldwide total is now triple that amount.

It's a figure that also places The Lion King in the top 10 best-selling soundtracks of all time. Indeed, it's Disney's only representative in the list, which includes Prince's Purple Rain, James Horner's Titanic, and Bee Gees' Saturday Night Fever, as well as the "I Will Always Love You"-featuring The Bodyguard at No. 1. (It still has a way to go to beat John's commercial peak, though. Goodbye Yellow Brick Road has reportedly sold an astonishing 20 million since its release in 1973.)

It Made GRAMMY History

It wasn't just at the box office where Disney firmly established its second golden age. Before the release of 1989's The Little Mermaid, the Mouse House hadn't attracted GRAMMYs attention once. By the turn of the century, however, they'd racked up a remarkable 30 nominations and 17 wins — and The Lion King played a major part in this awards dominance.

In fact, it made history by becoming the first Disney winner of both Best Male Pop Vocal Performance ("Can You Feel the Love Tonight") and Best Musical Album For Children, while "Circle of Life" picked up Best Instrumental Arrangement With Accompanying Vocals, too. The Lion King also followed in the footsteps of The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin by picking up the Academy Awards for both Best Original Song and Best Original Score.

It Started A Trend Of Pop Artist Composers

While Celine Dion, Peabo Bryson and Regina Belle had all previously lent their vocals to Disney's second golden age, The Lion King was the studio's first soundtrack to give a pop star composing duties. Alongside Tim Rice, the celebrated lyricist who'd worked on Aladdin, Elton John wrote all five of the album's vocal numbers. And it was a setup that appeared to give several of his peers ideas.

Randy Newman had already picked up Academy Award nods for his composing talents on 1981's Ragtime. But it wasn't until 1995's Toy Story that the singer/songwriter began the fruitful Disney animation partnership that would also take in the Monsters Inc. and Cars franchises. In 1999, Phil Collins co-wrote and performed the entirety of Tarzan's pop soundtrack. And four years later, Carly Simon decided to get in on the Mouse House action by pulling double duty on seven songs for Piglet's Big Movie.

It Introduced Hans Zimmer To Animation

The Prince of Egypt, The Road to El Dorado, Madagascar, and The Simpsons Movie are just a few of the hit animations to have benefitted from Hans Zimmer's Midas touch. But it wasn't until 12 years into his career that the German composer proved that his talents could be used just as effectively in the world of animation as live-action. And The Lion King was the catalyst.

Zimmer provided four instrumental pieces for the Disney phenomenon including "This Land," "To Die For," and "King of Pride Rock," also bagging two GRAMMYS, an Oscar and a Golden Globe for his efforts. And as he told Classic FM while promoting his work on the 2019 remake, he has a certain family member to thank. "My daughter was 6 years old. I'd never been able to take her to any premieres, and Dad likes to show off."

It Spawned Several Crossover Hits

Although Beauty and the Beast and Aladdin had both spawned big Hot 100 hits (the chart-topping "Beauty and the Beast" and Dion and Bryson's "A Whole New World," respectively), The Lion King was the first Disney soundtrack to produce two. "Can You Feel The Love Tonight" reached No. 4 in the U.S. (and No.1 in Canada and France), while "Circle of Life" peaked at No. 18. Even "Hakuna Matata" saw some Billboard action, gracing both the Hot Adult Contemporary Tracks and Bubbling Under charts.

You're unlikely to ever see Elton John performing the latter – four of the film's cast members including Nathan Lane provided the vocals. But the two official singles have remained staples of both his live shows and countless compilations ever since. And they've crossed over to the Spotify age, too, with "Circle of Life" racking up103 million streams and "Can You Feel The Love Tonight" a whopping 322 million.

It Birthed Broadway's Biggest Hit

Hitting the New Amsterdam Theatre in October 1997, The Lion King wasn't the first Disney animation to get a Broadway stage adaptation (Beauty and the Beast had opened at the Palace Theatre three years earlier) — but it remains the biggest. In fact, thanks to a run of 8,500 shows, its $1 billion-plus gross is now the highest in the theater district's history.

The Lion King has also made it around the world, picking up numerous Tony and Olivier Awards along the way. And as you'd expect, the film soundtrack's pop numbers have been just as pivotal to the theater production's success as its immersive set design, powerhouse performances, and jaw-dropping puppetry.

Those lucky enough to see the spectacle before 2010 would also have enjoyed something of a lost classic. Sung by Mufasa's hornbill advisor Zazu, the John/Rice-penned "The Morning Report" was omitted from the 1994 film but enjoyed a 13-year run in the stage show's opening act.

It Covers A Vast Range of Styles

"The plan was that we wouldn't write the usual Broadway-style Disney score," John later wrote in his 2019 memoir, Me, about his and Rice's approach to the film. "But try and come up with pop songs that kids would like."

Indeed, while the partnership of Menken and Ashman grounded their Disney sing-alongs in the worlds of musical theater and Tin Pan Alley, the new dream team were determined to venture outside the Mouse House's comfort zone.

The Lion King OST boasts everything from carefree novelty sing-alongs ("Hakuna Matata") and emotive showstoppers ("Can You Feel The Love Tonight") to campy villain songs ("Be Prepared") and rumba rockabilly ("I Just Can't Wait To Be King"). And then there's Zimmer's instrumental pieces that typically begin with cinematic strings before building up to a Zulu choir crescendo, immediately transporting listeners to the vast landscape of Pride Rock.

It Kickstarted Elton John's Second Career

"I sat there with a line of lyrics that began, 'When I was a young warthog,'" John told Time magazine in 1995 about the inception of The Lion King soundtrack, "and I thought, 'Has it come to this?'"

The pop legend needn't have worried. The song in question, "Hakuna Matata," might not have been his most lyrically sophisticated. But the comic interlude proved that John could put an infectious melody to literally any subject. And alongside his four other contributions, it gave him the impetus to further explore the world of musical theater.

The Brit subsequently reunited with Rice for 2000's Aida, a pop-oriented adaptation of Giuseppi Verdi's same-named opera which earned a GRAMMY for Best Musical Show Album in 2001. And then in 2005, John struck Broadway gold once again with the multiple Tony Award-winning screen-to-stage transfer of ballet drama Billy Elliot. That same year, he also teamed up with regular collaboratorBernie Taupin on the score for Lestat, a musical version of Anne Rice's The Vampire Chronicles.

It Formed Part Of The 2019 Remake

Proof of just how well The Lion King soundtrack has endured came in 2019 when Jon Favreau's live-action remake borrowed all five of its vocal numbers. The performers were different, of course — see the likes of John Oliver on "I Just Can't Wait To Be King," Beyoncé and Donald Glover on "Can You Feel The Love Tonight," and Seth Rogen and Billy Eichner on "Hakuna Matata." But while Zimmer's reimaginings gave them an additional African flavor, the songs didn't stray too far from the source material.

But even with a starrier cast and a bunch of new compositions and covers, the new Lion King OST failed to strike the same chord with the cinemagoing public, selling just a fraction of its predecessor. Even Beyoncé's flagship single "Spirit" failed to peak any higher than No. 98 on the Hot 100. Sometimes, the originals truly are the best.

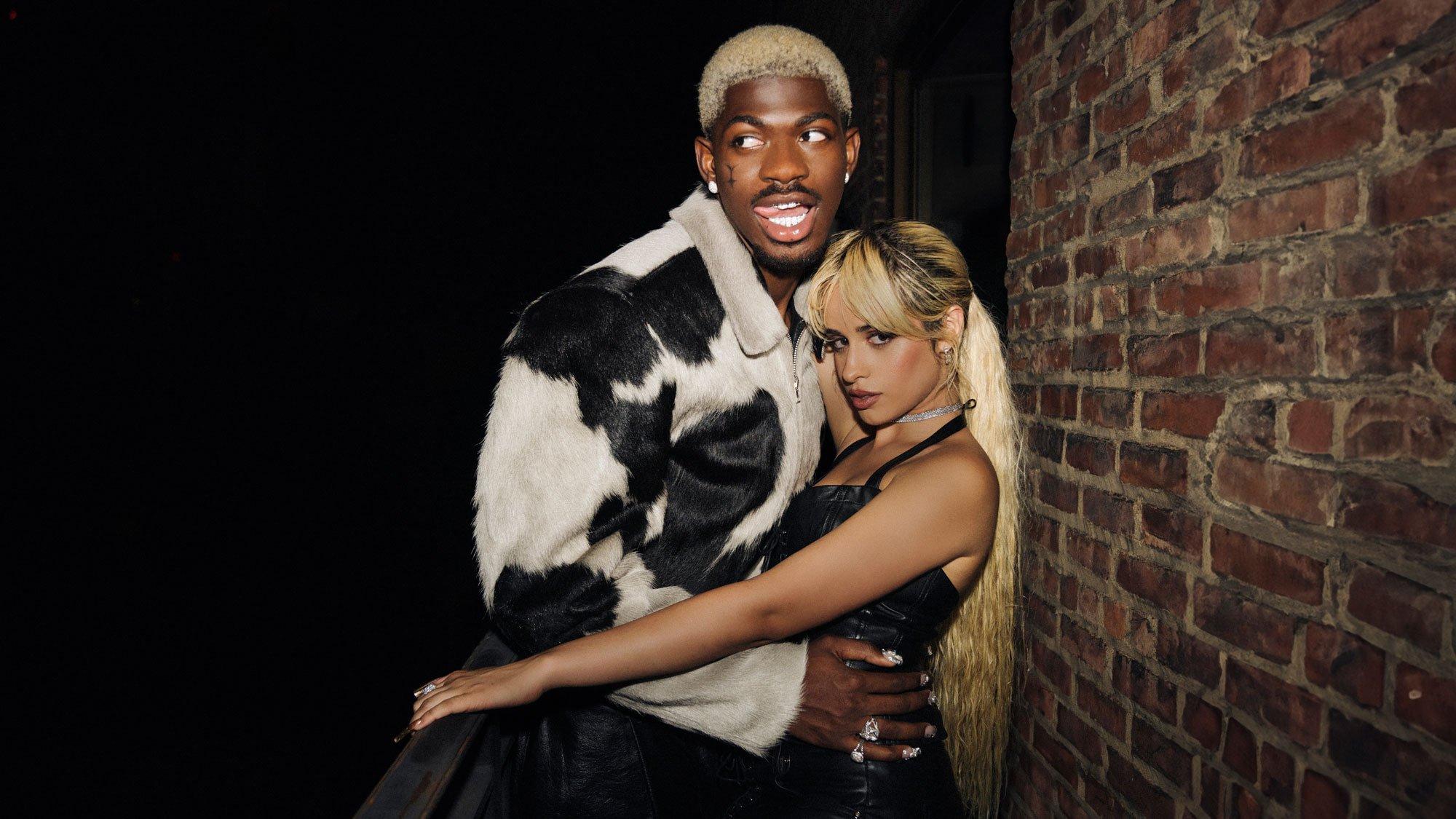

Photo: Courtesy Camila Cabello & Lil Nas X

list

New Music Friday: Listen to Songs From Megan Thee Stallion, Camila Cabello & Lil Nas X, BTS' RM & More

May 10 is quite the stacked day of new music across all genres — from Post Malone & Morgan Wallen's country collab, to Stray Kids' team-up with Charlie Puth, to The Chainsmokers and Kings of Leon. Check out some fresh releases to enjoy this weekend here.

As the summer quickly approaches, artists from every genre continue to unveil new music for warmer weather. Friday May 10 is particularly packed with anticipated and surprise releases from both emerging talents and established names.

The new albums alone prove just that: pop songsmith Alec Benjamin's 12 Notes, folk-rock band Judah & the Lion's The Process, regional Mexican stars Grupo Frontera's Jugando a Que No Pasa Nada, and GRAMMY-winning R&B singer Andra Day's Cassandra, to name a few.

Meanwhile, a big, cool glass of major rap releases is here to help wash down the piping hot Kendrick and Drake beef served up over the last week. Full album releases debuted from Gunna, Chief Keef, and Ghostface Killah — the latter featuring guest spots from Nas, Kanye West, Raekwon, Method Man and more. Hottie Megan Thee Stallion's powerful new single, "BOA", sets the stage for her Hot Girl Summer tour which officially starts on May 14. New songs from Ice Spice, Kodak Black, NLE Choppa, Coi Leray, G-Eazy, Yung Gravy, Ski Mask the Slump God set the playlist for a weekend full of slappers.

There's tons of collaborations, too, including the much-teased pairing of Post Malone and Morgan Wallen with "I Had Some Help," a track that showcases Malone's furtherance into country in a catchy, reflective anthem. But country music lovers also have more to enjoy this weekend: Orville Peck's duets project, Stampede Vol.1, features the likes of Willie Nelson and Elton John," while Scotty McCreery's Rise & Fall and Avery Anna's single "Blonde" fill the fuel tank for a rodeo-ready summer.

BTS's RM delivers another solo track "Come Back to Me" and Stray Kids dropped a new collaboration with Charlie Puth, coming fresh off the K-pop group's appearance at the Met Gala earlier this week. And the electronic and rock scenes are not left behind, with A.G. Cook exploring a new twist on Britpop and Sebastian Bach's release of Child Within The Man.

Dive into today's releases from Megan Thee Stallion, The Chainsmokers, RM, Stray Kids with Charlie Puth, Camila Cabello with Lil Nas X, Post Malone and Morgan Wallen below.

Megan Thee Stallion, "BOA"

Megan Thee Stallion's new single "BOA" continues to play up the themes of empowerment and self-realization that define her current musical phase and comes just days ahead of her Hot Girl Summer Tour starting on May 14. The song's cover art features Megan with a striking snake, a recurring symbol of rebirth that has been significant in her recent work, appearing in tracks like the Billboard Hot 100 hit "Hiss" and the 2023 song "Cobra."

"BOA" is a continuation of Megan's snake-themed narrative, but serves as a saccharine homage to her favorite late-'90s and early 2000s anime and video game classics. The music video features references to Scott Pilgrim, One Piece, Dance Dance Revolution, and iconic 3D fighting games like Mortal Kombat, complete with visuals and Gantz-inspired outfits.

Speaking to Women's Health about her upcoming summer album, Megan discussed the personal growth and renewal she has experienced, inspiring this new era of music. "I was inspired to create this album about rebirth because I feel I am becoming a new person physically and mentally," she shared.

Camila Cabello & Lil Nas X, "HE KNOWS"

Camila Cabello teams up with Lil Nas X for the tantalizing new song "He Knows," delivering a radio-friendly track that's as catchy as it is lustful. The new music mirrors the infectious energy of their recent appearance at FKA Twigs' Met Gala afterparty, where they both were seen dancing the night away behind the DJ booth.

"He Knows" serves as a precursor to Cabello's highly anticipated fourth solo album, C,XOXO, — set to drop on June 28 — and teases a glimpse of Cabello's evolving artistic direction. The single follows on the heels of her recent hit "I LUV IT" featuring Playboi Carti, part of the reimagining of her sound and artistic brand.

RM, "Come Back To Me"

BTS member RM has released a new single, "Come Back To Me," accompanied by a music video. The relaxed track gives fans a taste of his upcoming second solo album, Right Place, Wrong Person, set to release on May 24.

In the song, RM explores themes of right and wrong, capturing the complex emotions of wanting to explore new avenues while wishing to stay comfortable in the present. "Come Back To Me" features contributions from OHHYUK of the South Korean band HYUKOH, and Kuo of the Taiwanese band Sunset Rollercoaster. Additional credits include JNKYRD and San Yawn from Balming Tiger. RM first performed "Come Back To Me" during a surprise appearance at BTS bandmate Suga's concert in Seoul last summer, noting it as a favorite from his forthcoming album.

The music video for "Come Back To Me" was written, directed, and produced by Lee Sung Jin, known for his work on the Netflix show "Beef." The video features actress Kim Minha from the Apple TV+ series "Pachinko" and faces themes of identity and self-reflection, showing RM confronting different versions of himself. Its cast includes notable Korean and American actors such as Joseph Lee, Lee Sukhyeong, and Kim A Hyun.

Post Malone & Morgan Wallen, "I Had Some Help"

Post Malone and Morgan Wallen blend their distinct musical styles in the much-anticipated release of their collaborative single "I Had Some Help." Merging Malone's versatile pop sensibilities while leaning into his country roots with Wallen's, well, help, the duet is a unique crossover that has had fans clamoring to hear more since the two first teased the song earlier this year.

Finally premiering during Wallen's headlining performance at Stagecoach Festival on April 28, the uptempo song explores themes of mutual support and shared experiences, encapsulated by the lyric, "It ain't like I can make this kind of mess all by myself."

The collaboration has sparked significant buzz and showcases the duo's chemistry and shared knack for storytelling. This single highlights their individual talents as well as their ability to bridge genre divides, already promising to be a hit on the charts and a favorite among fans.

The Chainsmokers, No Hard Feelings

Maestros of mainstream emotion, The Chainsmokers continue to master the art of turning personal reflections into global anthems with their latest EP, No Hard Feelings. The six-song project see Alex Pall and Drew Taggart exploring the emotional highs and lows of modern relationships, weaving their signature dance beats with pop sensibilities as they have since 2015's "Roses."

The duo's latest release serves as a soundtrack to both sun-kissed days and introspective nights. The collection includes the single "Friday," a collaboration with Haitian-American singer Fridayy, described by the duo as a direct descendant of "Roses." Other tracks, such as "Addicted," also underscore the Chainsmokers' knack for capturing the zeitgeist of contemporary love and loss.

Kings of Leon, Can We Please Have Fun

Kings of Leon return with their signature blend of rock and introspection on their ninth studio album, Can We Please Have Fun. The LP finds the band infusing their established sound with fresh, unbridled energy, reminiscent of their early days yet matured by years of experience. The album features standout tracks like "Mustang" and "Nothing To Do," which mix playful lyrics with serious musical chops, showcasing Kings of Leon's unique ability to combine rock's raw power with catchy, thoughtful songwriting.

The band is set to bring Can We Please Have Fun to life on their 2024 world tour, starting in Leeds, United Kingdom on June 20 and wrapping in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on Oct. 5. Fans can expect a high-energy series of performances that blend new tracks with beloved classics, all delivered with the Kings of Leon's legendary fervor.

Stray Kids & Charlie Puth, "Lose My Breath"

Stray Kids have teamed up with Charlie Puth for their latest release, "Lose My Breath," a track that blends K-pop dynamism with Western pop flair, written by Stray Kids' own producer team 3racha (Bang Chan, Changbin, and Han) along with Puth. The TK song details a whirlwind of emotions, describing symptoms of breathlessness and heart-palpitating moments encapsulated in the lyrics: "I lose my breath when you're walking in/ 'Cause when our eyes lock, it's like my heart stops."

"Lose My Breath" is described as a "warm-up" for Stray Kids' forthcoming album, set for release this summer. The track further highlights the global appeal of Stray Kids ahead of their highly anticipated headlining set at Lollapalooza in August. It also continues Puth's engagement with K-pop, following his previous work with other K-pop acts including his collab with BTS' Jungkook, "Left and Right," and "Like That," a song he co-wrote for K-pop girl group BABYMONSTER.

15 Must-Hear Albums In May 2024: Dua Lipa, Billie Eilish, Sia, Zayn & More