Studied observers know that hip-hop rarely goes along to get along, or consents to being made a cat's paw of. The genre is punker than punk. When Ronald Reagan's austerity government caused deep harm to Black communities, hip-hop spoke up, asserting its humanity with albums like It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back by Public Enemy and Pure Righteousness by Lakim Shabazz. And when subsequent presidents beefed up their strategies of surveillance and entrapment, hip-hop spoke up again; sometimes in song—who could forget Ice-T's disavowal of the security state on "Drama"?)—and sometimes in person. In fact, X Clan were among the demonstrators who in 1989 descended on hostile territory for a Day of Outrage.

But hip-hop responded differently to COVID-19, even when the pandemic snarled Black and brown people like nobody else. It's not like life continued as normal. How could it with so many rappers' livelihoods hanging perniciously in the balance? But many would argue the hip-hop community didn't push back all that forcefully on the bunglers of our national COVID-19 response. There were hand-washing PSAs aplenty, but very few howls of indignation.

Does this mean the flames of revolt have been extinguished? Absolutely not. Thirteen-time GRAMMY winner Kendrick Lamar—a familiar face at police reform rallies—shares his forebears' penchant for protest. So do Jay Electronica (a GRAMMY nominee), Isaiah Rashad, Noname, and others.

Below are nine hip-hop albums of "revolutionary" character. Some are faith-based; others advance a Black nationalist or Marxist perspective. But they all exude Black solidarity and revolutionary fervor.

Related: From Aretha Franklin To Public Enemy, Here's How Artists Have Amplified Social Justice Movements Through Music

Jungle Brothers, Straight Out The Jungle (1988)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/9UdIltEYziA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Where would hip-hop be without the Jungle Brothers? On Straight Out The Jungle, the Harlem trio sculpted verdant soundscapes that were at once naturalistic and futuristic. They improvised rhymes with effortless deft. They created out of whole cloth wonderfully lifelike characters. ("Jimbrowski" introduces us to Dreadlock Man, a lion-maned prophet of truth.) And they cleared a path for plucky, socially conscious overachievers from De La Soul to A Tribe Called Quest to Black Sheep.

Hip-hop was still very young in 1988, but already it was the target of a disinformation campaign. Rappers were said to be "small-minded," slothful, materialistic, basically pliant stooges for the sportswear industrial complex. Thank god for Straight Out The Jungle. Much like De La Soul's 3 Feet High and Rising, which came out the following spring, Jungle rebutted the most intransigent mistruths about hip-hop and Black youth culture more generally.

Poor Righteous Teachers, Holy Intellect (1990)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/gfMURCgM3GY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Miraculously, the Five Percenter community was big enough to accommodate Poor Righteous Teachers and Brand Nubian. Both were professorial, tough as leather and unyielding in their convictions; stenographers to no one except Allah. Both could be high-handed and self-regarding, yet they coexisted without incident.

Brand Nubian was a great group, but too homophobic to pass moral muster. To its credit, Holy Intellect doesn't wade nearly so deeply into hip-hop's confected gay panic. The album is about three things: Allah's grace, Allah's mercy and Allah's beneficence. This is weighty stuff, to be sure. Luckily, the music is effervescent, with turntable scratches, rolling triplets, harmonica flourishes, and Doors-style organs.

Divine Styler, Spiral Walls Containing Autumns of Light (1992)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/B179i79LtkA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Divine Styler had a minor hit with 1989's "Ain't Savin' Nothin'." At that point in his career, he bore the impression of a chin-stroking sonneteer making music for coffee shop revolutionaries. But Styler underwent a dramatic transformation, and he did it inside of three years; by '92, all that remained of his former self was the hushed spoken-word cadence.

Spiral Walls is gutsy and eclectic—very, very brazenly eclectic. The polarity between hip-hop and noise rock, or hip-hop and exotica, ceases to matter. These are all just ingredients in a bitchin' brew concocted by Styler, the gamest fusionist you'll ever meet.

We haven't even gotten to Styler's writing, which is breathy at times and garrulous in a way that only he could be. But no one can deny the extraordinary scope of his imagination. A devout Muslim, Styler, like so many Black men, was born anew in the image of Allah, who he credits for his creative, not just spiritual, awakening.

The Coup, Genocide & Juice (1994)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/EHWMRFWXsK8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The Bay Area might vote reliably blue, but there is no love lost between Boots Riley and America's oldest bourgeois party. Riley will probably never perform at an inauguration ball or headline a Democratic fundraiser. He's not a Democrat; he's an unreconstructed Marxist-Leninist-Trotskyist, and he's suspicious even of like-minded people with pretensions to the electoral office.

Genocide & Juice is refreshing, not least because it affords us a rare opportunity to hear about class exploitation from afflicted persons. Riley is a relatively anonymous gear in the capitalist machine, not a paid politico, well-coiffed pundit, or tenured academic. And on Genocide & Juice, he rails jocularly and impassionedly against the people: landlords, debt collectors, prosecutors, energy monopolists, CIA spies--who not only butter his congressperon's bread but make life hell for working Black folk.

Black Star, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star (1998)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/YqYeTjeRJ84' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Mos Def is a competent yodeler and raps in a twangy patois over island-inspired sampledelia. (Give him a crate full of dub or reggae 45s and presto—a great song is born.) Talib Kweli is no flyweight, either. His flow—sturdy as stucco and fearsomely articulate—is one reason Black Star's 1998 debut album, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star, has held up through the millennia. He also makes powerful cases against colonialism, consumerism, colorism, and every dastardly "ism" in between. Still, this album is remarkable for its unqualified positivity.

BUSDRIVER, Fear Of A Black Tangent (2005)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/Egi_pI81Ja8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Rich kids do the damnedest things. Given his penchant for undecodable jabberwocky, you might assume that BUSDRIVER was raised by wolves. But no: He's the son of a screenwriter, showrunner, and all-around straight arrow (Ralph Farquhar, whose credits include "Moesha"). Despite his fortuitous background, BUSDRIVER has always felt most at home in the wacky world of mass transit.

Fear Of A Black Tangent's production is slightly gauzy, but it doesn't matter because BUSDRIVER's protestations are so spot-on. He calls out the white establishment for its persnickety elitism and credential humping: "They want to hear good freestyling with the sarcasm of Woody Allen," BUSDRIVER raps on "Cool Buzz Band." BUSDRIVER is many critics' Platonic ideal of a rapper: smart, adenoidal, free-associative, self-lampooning. But he's tired of being fetishized as "one of the good ones," and he's tired of bohemian critics with denigrative attitudes about hip-hop. "I'm a post-rap wizkid," he says on the mocking "Sphinx's Coonery." "My speech is littered with double entendres and sharp sarcasm."

Kendrick Lamar, To Pimp A Butterfly (2015)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/iIsHg3BHpB0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Imagine if Adrian Nicole LeBlanc had followed up her groundbreaking book "Random Family" with a scrapbook of fortune-cookie-like benedictions, incantations and truisms. That's sort of what Kendrick Lamar did. His 2012 breakout, good kid, m.A.A.d. city, was like a Victorian novel, densely plotted and stuffed to the brim with interweaving characters.

To Pimp A Butterfly is different. The record mosies along at an unbothered pace, lapping up the borrowed wisdom of Lamar's elders. Typical of To Pimp A Butterfly is "Institutionalized," where Lamar's grandmother is quoted as telling her grandbabies, "Don't s*** change until you get up and wash your ass."

Loving TPAB, by far the most inward-looking and "experimental" of Lamar's four studio albums, is, to quote "U," complicated, at least for those who prefer K.Dot as the rough-and-ready, battle-rapping prole from times past. But even when he's singing—in a coiled, stricken, serpentine falsetto—Lamar has plenty to say about obstacles one faces when seeking self-love and self-cultivation in the Black underclass.

Read: Black Sounds Beautiful: How Kendrick Lamar Became A Rap Icon

Smino, blkswn (2017)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//S1J_lMSYigQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

If you find fault with Smino's unlofty personal commandment ("I know I'll be aight if I just make it through tonight," he raps on "Amphetamine"), it's because you live in a rose-scented never-never land. Smino does not. He's from North St. Louis, a poor, internally colonized lazaretto with one of the highest murder rates in the developed world. Ambition is a luxury Smino, a self-described "ashy lil' black boy," can ill afford; it's not a foundational human need.

Smino is flirtatious, even sex-mad, but he spends most of blkswn ducking and dodging oligarchs, not baby mamas. The corporate state has no use for "shiftless" Black youths like Smino—except, of course, in a 6-by-8-foot jail cell. The fidgety, cut-and-paste production is adventurous, and Smino is frantic in his febrile gaiety, but he hasn't gone daft. He's only too aware of what he's up against. "Life ain't even granted," he says on "Maraca". "Off the strength, I'm brown-skinned."

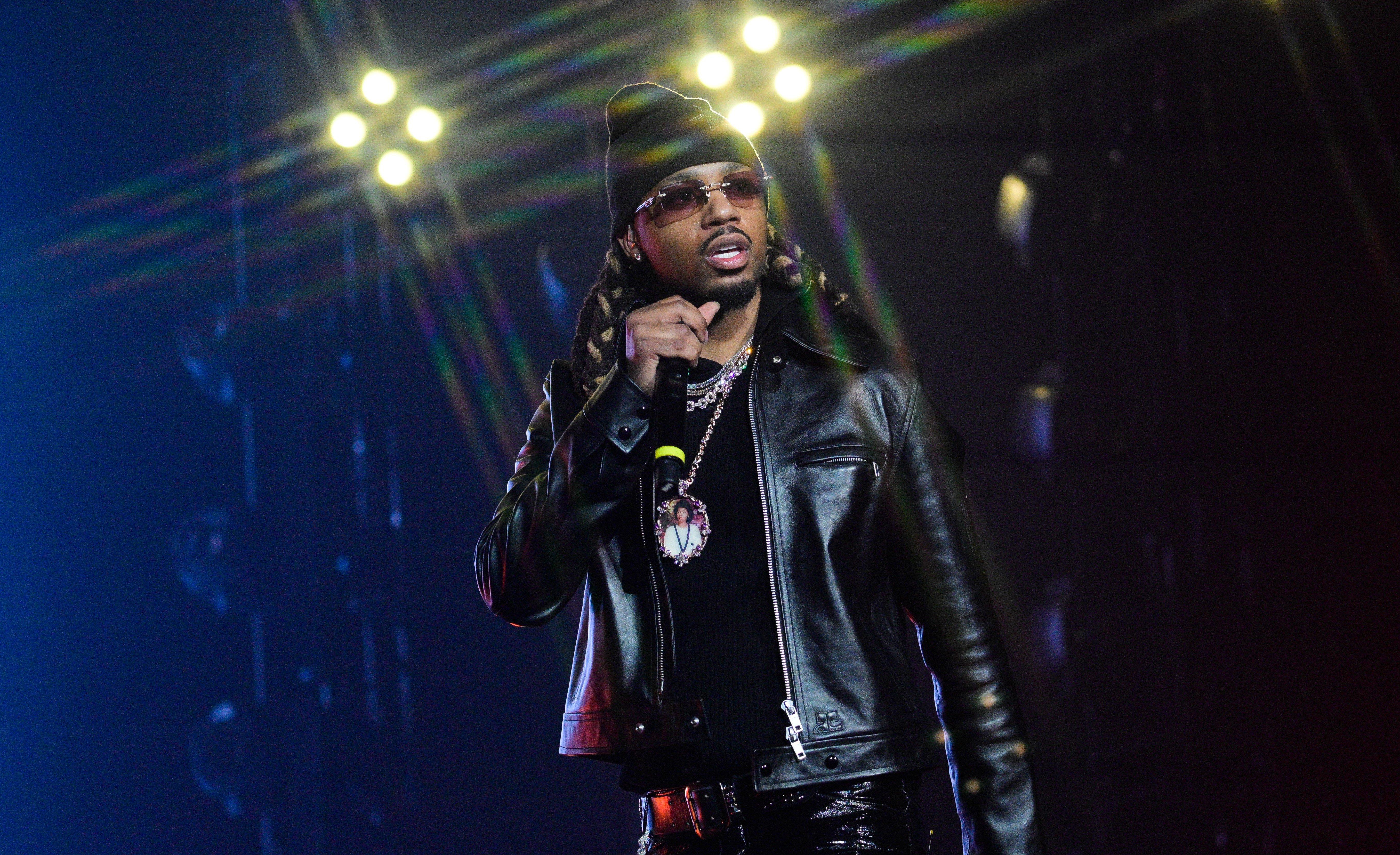

EarthGang, Mirrorland (2019)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/t5gh4uX-X40' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

EarthGang are an Atlanta duo with sherpa-like mountain endurance. The duo has been plugging along for nearly 15 years. In that time, many a nonbeliever has voiced displeasure with the duo's output, a spastic comingling of vaudeville, música latina and Southern trap; Twitter was not receptive when Julianna Godard likened EarthGang to a younger Outkast. For most of their career, though, EG were too marginal to generate significant hostility.

After years of thankless toil, EarthGang finally penetrated the mainstream with Mirrorland. Like Wakanda or Stankonia, Mirrorland is an egalitarian, vaguely transcendentalist, wholly self-ruling Black utopia. Based on communal ownership, Mirrorland nonetheless cherishes the sanctity of the individual. As Doctor Dut says on "Blue Moon," "We not each other's property."

Let Me Play The Answers: 8 Jazz Artists Honoring Black Geniuses