Photo: /AFP via Getty Images

list

From 'Shaft' To 'Waiting To Exhale': 5 Essential Black Film Soundtracks & Their Impact

Black film soundtracks have introduced countless bops and future household names into the mainstream. These soundtracks not only elevate narratives, but reinforce the emotional impact of movies that center the Black experience.

Black filmmakers have long understood the power of infusing music into their narratives. Whether it’s the tapping of the hi-hat at the beginning of "Theme From Shaft" or the warbly opening synth before Prince’s spoken-word intro on "Let’s Go Crazy," these signature sounds evoke a cinematic image that deepens the sonic and visual elements of a film.

As with most great innovations, the concept of working with a composer to create original sounds for film emerged from desperation. Trailblazing Black film auteur Melvin Van Peebles was eager to attract a larger audience for his 1971 Blaxploitation crime drama, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, and hired Earth Wind & Fire to score his X-rated opus about a Black hustler on the run from the law.

But instead of developing a string of new tracks reminiscent of their past work, the label-defying band created new sounds that served the narrative of Sweet Sweetback. Understanding that visibility is paramount for cinema, Van Peebles chose to release the soundtrack before the film to get people excited about the material — and his plan worked.

The film's success — with Black and non-Black audiences — led to a revolutionary shift in the relationship between music and cinema. Other productions adopted the tactic, including the 1972 crime drama Super Fly, and promotional soundtracks eventually became the status quo in Hollywood.

Prominent Black filmmakers continued the legacy of using music to drive and promote their narratives. In the '70s, some filmmakers gave the reins to a single artist, like Curtis Mayfield’s Super Fly and Stevie Wonder’s Jungle Fever. The late '80s and early '90s saw increasing popularity of compilations featuring notable and emerging acts, such as School Daze, Soul Food and Poetic Justice.

The mid-to-late '90s saw a rise of musicians-turned-actors like Will Smith and Whitney Houston, who received dual billing in movies and soundtracks such as Men in Black, Wild, Wild West, The Bodyguard, Waiting to Exhale and The Preacher’s Wife. (However, blurring the lines between music and acting was nothing new for Smith; the "Fresh Prince of Bel-Air" theme song has stamped a place in television history.)

And the tradition has continued into the new millennium. With its roster of G-Unit artists, 50 Cent's Get Rich or Die Tryin soundtrack is an East Coast descendant of 1994's Above the Rim, which features a lineup from the West Coast's Death Row Records. On the music-actor hybrid front, Beyoncé has carved out a lane similar to Whitney Houston, doing double duty for Austin Powers in Goldmember, The Fighting Temptations, Cadillac Records, Dreamgirls and 2019's The Lion King.

Compilations remain prevalent and popular. The 2015 sports drama Creed is supercharged by hip-hop and R&B tracks from Meek Mill, Jhené Aiko, Donald Glover, Future and Vince Staples, while neo-soul grooves from Lucky Daye, H.E.R. and Robert Glasper reinforce the story of Black love on The Photograph's soundtrack. The soundtrack for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever spans genres, with songs by E-40, Burna Boy, and Rihanna that showcase the vast world of Wakanda.

Scores of memorable Black film soundtracks have been released since Van Peebles inextricably linked film and soundtrack in the early ‘70s. The following selections are just a sample of the essential titles that have left an indelible mark on both Black music and cinema:

Shaft

"My only responsibility was to make sure [director Gordon Parks] didn’t hand me my head on a platter," Isaac Hayes once said about this iconic 1971 theme song. "It was my first movie gig and I wanted to make sure I did it right."

And the Oscar and GRAMMY Award-winning singer did just that. From the energetic clinking of the hi-hats to the exquisitely slow, nearly three-minute build toward the sound of Hayes’ silky-smooth baritone, the theme to Shaft delivers on all levels — both as a theme for the hippest, no-nonsense private detective in the game, as well as a stand-alone jam that went hard as hell at the disco.

The Shaft soundtrack — a double album by Hayes recorded specifically for the film — also features a mix of orchestrated instrumental tracks that have inspired generations of Black artists. The award-winning composition has been sampled hundreds of times since its release; Erykah Badu ("Bag Lady"), Dr. Dre ("Xxplosive") and Adina Howard ("If We Make Love Tonight") have all put their spin on "Bumpy’s Lament."

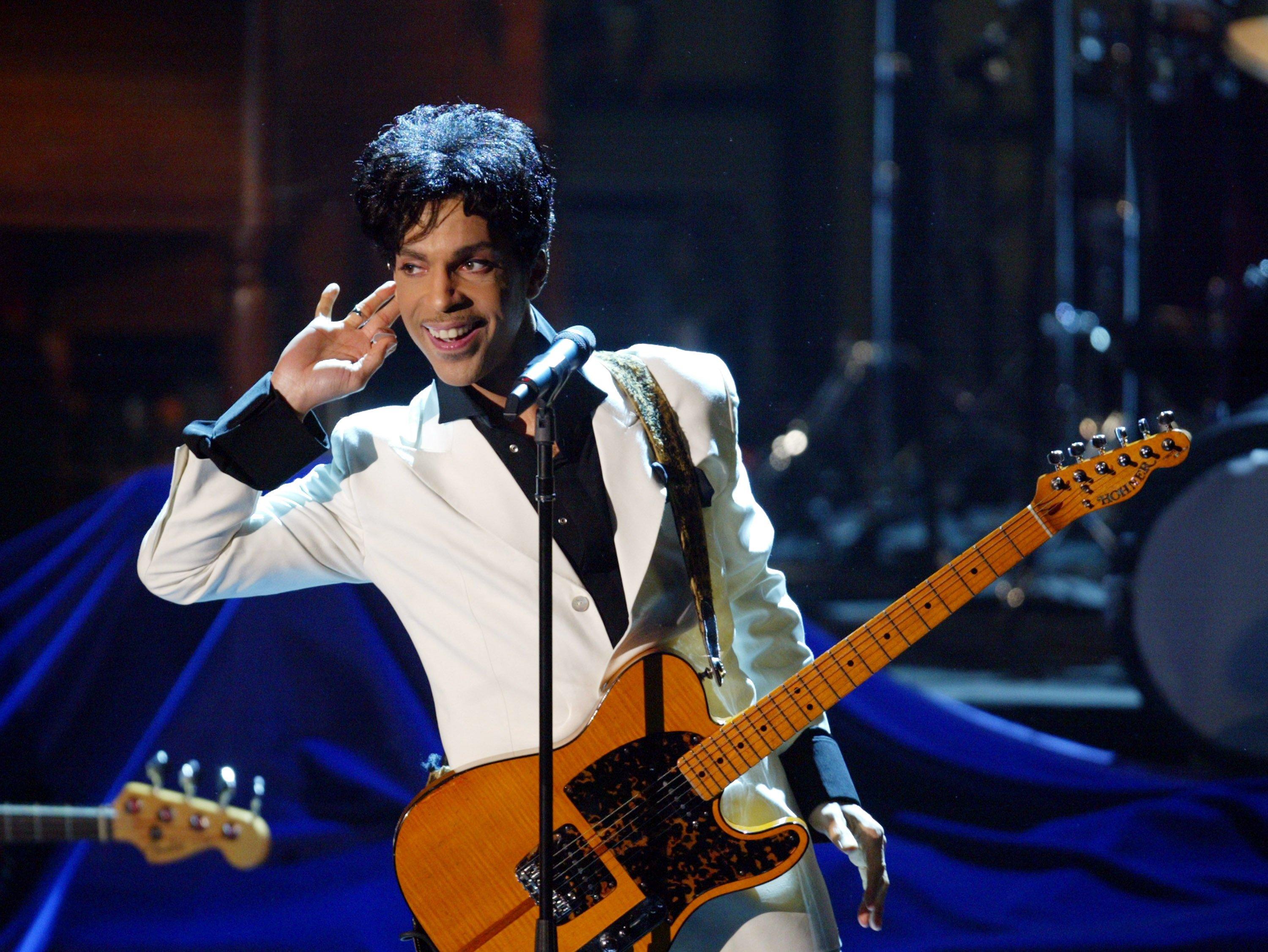

Music From the Motion Picture Purple Rain

Nearly 40 years after its release, the 1984 film that launched Prince into mega-stardom continues to attract new audiences — thanks in great part to its transcendent soundtrack. Created in collaboration with his backing band the Revolution, Prince’s game-changing studio album spent 24 weeks at the top of the Billboard charts. It birthed a string of Top 10 hits, including "Let’s Go Crazy," "I Would Die 4 U," "When Doves Cry," and the title track, "Purple Rain."

Blending elements of funk, rock, synth pop, and R&B, the iconic album attracted a wide cross-section of fans and has become a hallmark of ‘80s music. And none of it would be possible without Prince’s desire to break from convention — he wanted the world’s attention. So he went to work forming a backing band of young musicians from different identities who could help him capture the rock 'n’ roll energy of ‘80s mainstream acts like Bob Seger. After carefully developing stage personas, rehearsing nonstop, and cultivating the right sound, Prince compiled their tracks — alongside a few songs from Apollonia 6 and the Time — and the rest is history.

The high-energy, genre-blending album was met with acclaim and earned the singer three GRAMMYs and an Academy Award for Best Original Score Song. But perhaps most importantly, Prince’s willingness to experiment gave the green light to a host of artists from different genres who followed in his path, including Beck, Janet Jackson, Beyoncé, U2, Cyndi Lauper, Dave Grohl and more.

Music From Do the Right Thing

Throughout his successful decades-long career, renowned film director Spike Lee has seamlessly weaved music into his narratives to elevate and highlight emotional themes. Whether he’s deploying a rare acapella recording of Marvin Gaye’s "What’s Going On?" during a pivotal scene in Da 5 Bloods or using Sam Cooke’s 1963 song "A Change is Coming" in a montage before the civil rights leader’s assassination in Malcolm X, Lee understands the emotional power of music and how to leverage it in his work.

And while it’s difficult to pick a true stand-out in a filmography bursting with memorable musical moments, the soundtrack for Lee's 1989 masterpiece Do the Right Thing is arguably among the most noteworthy because of Public Enemy’s "Fight the Power" — a head-bopping call to action that introduced the group into the mainstream.

Back in the late ‘80s, when Lee was searching for an anthem for his upcoming indie film about racial tensions in a Brooklyn neighborhood, he reached out to Public Enemy to ask them to do a hip-hop-infused spin on the Black National Anthem, "Lift Every Voice and Sing." But they were not interested.

"I opened the window and asked him to stick [his] head outside. ‘Man, what sounds do you hear? You’re not going to hear ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ in every car that drives by,’" Public Enemy co-founder Hank Shocklee told Rolling Stone. "We needed to make something that’s going to resonate on the street level. After going back and forth, he said, ‘All right, I’ll let you guys go in there and see what you guys come back with.’"

So the influential hip-hop group hit the studio, first nailing down the name of the record — inspired by the Isley Brothers’ song of the same name — then working on the instrumentation and lyrics. After sending Lee a rough version of the track, he suggested that they add saxophone and jazz great Branford Marsalis was brought in. Public Enemy added three of his sax solos to the song, and Lee was so taken with the track that he used it in the movie 20 separate times.

While the soundtrack also features high-energy party songs from ‘90s R&B staples like Guy and Teddy Riley, the Experience Underground (best known for "Da Butt") and a soul-searching ballad from Al Jarreau, Public Enemy’s groundbreaking protest track remains the perfect embodiment of the movie’s central message and energy. "Fight the Power" fused two traditional Black music forms, jazz and hip-hop, to create an empowering, thought-provoking song that highlights the socio-political issues that the Black community continues to face nearly 40 years later.

Above the Rim (The Soundtrack)

Basketball and hip-hop go together like ice cream and cake. And this soundtrack for the 1994 sports drama about a New York high schooler caught between two worlds showcases the power of this perfect pairing. Off the strength and long-lasting impact of Warren G and Nate Dogg’s "Regulate" alone, this all-star compilation executive produced by Dr. Dre and Suge Knight has become a foundational Black movie soundtrack.

And while the tale of Warren and Nate’s incredibly tense night out may be the album’s most successful track, it’s part of an elite roster of ‘90s hip-hop and R&B acts, including SWV, The Lady of Rage, Al B. Sure, Tha Dogg Pound (featuring rising star Snoop Dogg), H-Town and the film’s star Tupac Shakur.

Released by Death Row Records and Interscope, the star-packed compilation hinted at the emerging rivalry between East and West Coast rappers. Yet audiences from both coasts fell in love with the record, which sold more than two million copies and ascended to the top of the Billboard R&B charts. The soundtrack’s success helped cement Death Row — and the gangsta rap genre — as a force to be reckoned with in the mainstream.

Waiting to Exhale: Original Soundtrack Album

Based on the best-selling Terry McMillan novel of the same name, Waiting to Exhale is a romantic drama that follows a close-knit group of Black women as they navigate challenging relationships, careers and family issues. Starring Whitney Houston, Loretta Divine, Angela Bassett and Lela Rochon, the film is among the most revered in the Black movie canon due to its authentic portrayals of Black sisterhood, relatable relationship issues and empowering themes. So when it was time to develop the film’s sound, it was important that the music uplift the story — but it did so much more than that thanks to the golden ears of Houston and GRAMMY-winning songwriter and producer Babyface.

In a recent appearance on the "The Kelly Clarkson Show," Babyface revealed that Waiting to Exhale director Forest Whitaker had originally asked Quincy Jones to write and produce the soundtrack. However, Jones declined and told the actor-turned-director to reach out to Babyface, who he thought was a better fit for the project.

In collaboration with Whitaker, Babyface and Clive Davis, Houston — who had final approval on the roster of featured artists — helped select an inspired mix of emerging stars, established acts and legendary songstresses: SWV, CeCe Winans, Toni Braxton, Faith Evans, For Real, Sonja Marie, Brandy, Shanna, Chanté Moore, Aretha Franklin, Chaka Khan, Patti LaBelle, Mary J. Blige, and of course, Houston, who was featured on three tracks: "Exhale (Shoop Shoop)" "Count on Me" and "Why Does It Hurt So Bad?"

Much like the film, the timeless compilation — which topped the charts and scored multiple top-10 hits along with a GRAMMY and an American Music Award — is a highly celebrated work of art created by Black women that continues to resonate with music fans everywhere.

Photo: Ross Marino/Getty Images

list

7 Reasons Why Prince's 'Purple Rain' Is One Of Music’s Most Influential Albums

In honor of the 40th anniversary of 'Purple Rain,' dig into the ways Prince's magnum opus didn't just solidify him as an icon — it changed the music industry and culture at large.

"I strive for originality in my music," Prince declared in a 1985 interview with MTV. "That was, and will always be the case."

It was this determination to do things his own inimitable way that birthed the decade's most audacious superstar project: Purple Rain.

Prior to the album's June 25, 1984 release, Prince had scored some mainstream hits — including "1999" and "Little Red Corvette" — but hadn't fully blossomed into the prolific, world-conquering musical hero he's now immortalized as. Nor did he have acting experience. Yet, Prince somehow managed to convince his management and label into financing a big-screen hybrid of romance, drama and musical accompanied by an equally ambitious pop soundtrack.

It was an inherently risky career strategy that could have derailed the Purple One's remarkable rise to greatness in one fell swoop. Instead, Purple Rain enjoyed blockbuster success at both the box office and on the charts, with the film grossing more than $68 million worldwide and the album topping the Billboard 200 for a remarkable 24 weeks.

Initially conceived as a double album featuring protege girl group Apollonia 6 and funk rock associates the Time, the Purple Rain OST worked as an entirely separate entity, too. In fact, it had already sold 2.5 million copies in the States before the movie hit theaters, largely thanks to the immediacy of lead single "When Doves Cry," Prince's first ever Billboard Hot 100 No. 1.

And a full 40 years on from its release, Purple Rain's diverse range of power ballads, hard rockers and party anthems still possess the power to stun, whether the phrase "You have to purify yourself in the waters of Lake Minnetonka" is familiar or not. Here's a look at why the GRAMMY-winning record — and 2010 GRAMMY Hall of Fame inductee — is regarded as such a trailblazer.

It Hopped Genres Like No Album Before

While the streaming age has encouraged artists and listeners to embrace multiple genres, back in the 1980s, "stay in your lane" was the common mindset. Of course, a musician as versatile and innovative as Prince was never going to adhere to such a restriction.

The Purple One had already melded pop, soul, R&B, and dance to perfection on predecessor 1999. But on his magnum opus, the star took his sonic adventurism even further, flirting with neo-psychedelia, heavy metal and gospel on nine tracks which completely eschewed any form of predictability. Even its most mainstream number refused to play by the rules: despite its inherent funkiness, "When Doves Cry" is a rare chart-topper without any bass!

As you'd expect from such a virtuoso, Prince mastered every musical diversion taken. And the album's 25 million sales worldwide proved that audiences were more than happy to go along for the ride.

It Championed Female Talent On And Behind The Stage

Although the likes of Jill Jones, Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman had contributed to previous Prince albums, Purple Rain was the first time the Purple One pushed his female musical proteges to the forefront. On "Take Me With U," he shares lead vocals with one of his most famous, Apollonia. On its accompanying tour, he invited Sheila E. to be his opening act. And in something of a rarity even still today, two of the soundtrack's engineers, Susan Rogers and Peggy McCreary, were women.

Melvoin and Coleman would go on to become artists in their own right as Wendy and Lisa, of course. And Prince would also help to radically transform Sheena Easton from a demure balladeer into a pop vixen; compose hits by the Bangles ("Manic Monday"), Martika ("Love Thy Will Be Done"), and Sinead O'Connor ("Nothing Compares 2 U"); and provide career launchpads for Bria Valente and 3RDEYEGIRL.

It Broke Numerous Records

As well as pushing all kinds of boundaries, Purple Rain also broke all kinds of records, including one at the music industry's most prestigious night of the year. At the 1985 GRAMMY Awards, Prince became the first Black artist ever to win Best Rock Performance By A Duo Or Group With Vocal, beating the likes of the Cars, Genesis, Van Halen, and Yes in the process. Purple Rain also picked up Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media at the same ceremony, and was nominated in the night's most coveted Category, Album Of The Year.

Another impressive feat was the one that had only previously been achieved by the Beatles and Elvis Presley. With the same-named movie also hitting the top of the box office chart, Prince became only the third artist in history to score a No. 1 album, film and song in the same calendar year.

It Changed How Albums Were Sold

Although it seems positively chaste compared to the likes of "WAP," "Anaconda," and "My Neck, My Back (Lick It)," Purple Rain's tale of a "sex fiend" who enjoys pleasuring herself in hotel lobbies was deemed so provocative at the time of release that it inadvertently instigated a political taskforce.

Appalled by the sexual lyrical content of "Darling Nikki," a track she caught her 11-year-old daughter Karenna listening to, future Second Lady Tipper Gore decided to set up the Parents Music Resource Centre with three other "Washington Wives." The organization subsequently persuaded the record industry and retailers to issue any album containing child-unfriendly material with Parental Advisory stickers. (Another Prince-penned hit, Sheena Easton's "Sugar Walls," was also included alongside "Darling Nikki" in the "Filthy 15" list of songs the PMRC deemed to be the most offensive examples.)

It Paved The Way For The Pop Star Film

Prince was the first pop superstar from the 1980s holy trinity to bridge the gap between Hollywood and MTV, with Purple Rain arriving eight months before Madonna's star turn in Desperately Seeking Susan and four years before Michael Jackson's fantastical anthology Moonwalker. And it spawned a whole host of similar vanity projects, too.

You can trace the roots of everything from Mariah Carey's Glitter to Eminem's 8 Mile back to the tale of a troubled musical prodigy — nicknamed The Kid — who finds solace from his abusive home life at Minneapolis' hottest night spot. And while the acting and screenplay were never going to trouble the Academy Awards (as lead actress Apollonia predicted, however, it did pick up Best Score), Purple Rain's spellbinding onstage performances captures the euphoria of live music better than any other concert film, fictional or real.

It Helped Redefine Masculinity in Pop

"I'm not a woman, I'm not a man/ I am something that you'll never understand," Prince sings on Purple Rain's biggest dance floor number "I Would Die 4 U" — one of many occasions in both the album and film that challenged notions of masculinity, gender and sexuality even stronger than the Purple One had before.

Indeed, although the early '80s was unarguably a boom period for white British pop stars outside the heteronormative norm, it was rarer to find artists of color so willing to embrace such fluidity. Prince, however, had no problem — whether sporting his now-iconic dandy-ish, ruffled white shirt and flamboyant purple jacket combo, or unleashing his impressive array of diva-like shrieks and screams on "Computer Blue" and "The Beautiful Ones." André 3000, Lil Nas X and Frank Ocean are just a few of the contemporary names who have since felt comfortable enough to express themselves in similarly transgressive fashion.

It Added To The Great American Songbook

From the apocalyptic rockabilly of "Let's Go Crazy" ("We're all excited/ But we don't know why/ Maybe it's 'cause/ We're all gonna die") and messianic new wave of "I Would Die 4 U," to the experimental rock of "Computer Blue" and self-fulfilling prophecy of "Baby, I'm A Star," Purple Rain delights at every musical turn. But it's the title track that continues to resonate the most.

Following Prince's untimely death in 2016, it was "Purple Rain" — not "1999," not "Kiss," not "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" — that many fans gravitated toward first. Initially conceived as a country duet with Stevie Nicks, the epic power ballad was described by Prince as pertaining "to the end of the world and being with the one you love and letting your faith/ God guide you through the purple rain."

The superstar acts every inch the preacher on the emotional tour-de-force. And as the final song that Prince ever performed live — on the Atlanta leg of his Piano & A Microphone tour, a week before his untimely passing — closed the curtains on a truly revolutionary career.

Photo: Kevin Kane/WireImage via Getty Images

list

7 Legendary Prince Performances You Can Watch Online In Honor Of 'Purple Rain'

Fans of the Purple One, unite: it's time to celebrate 40 years of 'Purple Rain.' Crank up these classic Prince performances in tribute to that epochal album, and beyond.

Have we really been living in a Princeless world for eight years? It doesn't feel like it. With every passing year, Planet Earth feels more of the magnitude of the Purple One's unbelievable accomplishments. Which includes the sheer body of work he left behind: his rumored mountain of unreleased material aside, have you heard all 39 of the albums he did release?

Yes, Prince Rogers Nelson was an impressive triple threat, and we'll likely never see his like again. In pop and rock history, some were wizards in the studio, but lacked charisma onstage, or vice versa: Prince was equally as mindblowing in both frameworks.

His iconic, GRAMMY Hall of Fame-inducted 1984 album Purple Rain — a soundtrack to the equally classic film — turns 40 on June 25. Of course, crank up that album's highlights — like "Let's Go Crazy," "When Doves Cry," and the immortal title track — and spin out from there to his other classics, like Dirty Mind, 1999, and Sign o' the Times.

To get a full dose of Prince, though, you've got to raid YouTube for performance footage of the seven-time GRAMMY winner through the years. Here are seven clips you've got to see.

Capital Centre, Landover, Maryland (1984)

Feast your eyes on Prince, the year Purple Rain came out. With guitarist Wendy Melvoin, keyboardist Dr. Fink, drummer Bobby Z., flanking him, even suboptimal YouTube resolution can't smother the magic and beauty. Check out this killing performance of Purple Rain's "I Would Die 4 U," where Prince's moves burn up the stage, with Sheila E. as much a percussion juggernaut as ever.

Read More: Living Legends: Sheila E. On Prince, Playing Salsa And Marching To The Beat Of Her Own Drum

Carrier Dome, Syracuse, New York (1985)

"Little Red Corvette," from 1982's 1999, has always been one of Prince's most magical pop songs — maybe the most magical? This performance in central New York state borders on definitive; bathed in violet and maroon, caped and cutting a rug, a 26-year-old Prince comes across as a force of divine talent.

Paisley Park, Minnesota (1999)

"I always laugh when people say he is doing a cover of this song… It's his song!" goes one YouTube commenter. That's absolutely right. Although "Nothing Compares 2 U" become an iconic hit through Sinead O'Connor's lens, it's bracing to hear the song's author nail its emotional thrust — as far fewer people have heard the original studio recording, on 1985's The Family — the sole album by the Prince-conceived and -led band of the same name.

Watch: Black Sounds Beautiful: Five Years After His Death, Prince’s Genius Remains Uncontainable

The Aladdin, Las Vegas (2002)

Let it be known that while Prince could shred with the best of them, he could equally hold down the pocket. This Vegas performance of "1+1+1=3," from 2001's The Rainbow Children, is a supremely funky workout — which also shows Prince's command as a bandleader, on top of the seeming dozens of other major musical roles he'd mastered by then.

Read More: Bobby Z. On Prince And The Revolution: Live & Why The Purple One Was Deeply Human

Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Induction (2004)

Words can't describe Prince's universe-destroying solo over the Beatles' "While My Guitar Gently Weeps," in front of an all-star band of classic rockers including Jeff Lynne, Tom Petty, and George Harrison's son, Dhani. At song's end, Prince's guitar wails for a few more rounds, he tosses his Telecaster into the pit, and he struts offstage. We'll never see his like again.

Super Bowl Halftime Show (2007)

If you're the type of Super Bowl devotee who skips the Halftime Show, please — make time for Prince. When he digs into the trusty "Let's Go Crazy," it's hard not to follow suit. With fireworks blazing, and the Love Symbol brightly illumined, Prince arguably outshined the football game — as he tumbled through inspired cover after cover, by CCR, Dylan, and more. Naturally, he crescendoed with "Purple Rain," augmented by the drummers of the Marching 100.

Read More: Behind Diamonds and Pearls Super Deluxe Edition: A Fresh Look At Prince & The New Power Generation’s Creative Process

Coachella (2008)

At Coachella 2008, Prince offered a bounty of karaoke-style yet intriguing covers — of the B-52's ("Rock Lobster"), Sarah McLachlan ("Angel"), Santana ("Batuka"), and more. Chief among them was his eight-minute take on Radiohead's (in)famous first hit, "Creep," with a few quixotic twists, including flipping the personal pronoun I to a very Prince-like U.

"U wish U were special, / So do I," he yelps in the pre-chorus. Oh, Prince: to quote the radio-edited, de-vulgarized chorus of "Creep," you were so very special.

8 Ways Musicology Returned Prince To His Glory Days

Photo: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Baby Keem Celebrate "Family Ties" During Best Rap Performance Win In 2022

Revisit the moment budding rapper Baby Keem won his first-ever gramophone for Best Rap Performance at the 2022 GRAMMY Awards for his Kendrick Lamar collab "Family Ties."

For Baby Keem and Kendrick Lamar, The Melodic Blue was a family affair. The two cousins collaborated on three tracks from Keem's 2021 debut LP, "Range Brothers," "Vent," and "Family Ties." And in 2022, the latter helped the pair celebrate a GRAMMY victory.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, turn the clock back to the night Baby Keem accepted Best Rap Performance for "Family Ties," marking the first GRAMMY win of his career.

"Wow, nothing could prepare me for this moment," Baby Keem said at the start of his speech.

He began listing praise for his "supporting system," including his family and "the women that raised me and shaped me to become the man I am."

Before heading off the stage, he acknowledged his team, who "helped shape everything we have going on behind the scenes," including Lamar. "Thank you everybody. This is a dream."

Baby Keem received four nominations in total at the 2022 GRAMMYs. He was also up for Best New Artist, Best Rap Song, and Album Of The Year as a featured artist on Kanye West's Donda.

Press play on the video above to watch Baby Keem's complete acceptance speech for Best Rap Performance at the 2022 GRAMMYs, and check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind.

How The 2024 GRAMMYs Saw The Return Of Music Heroes & Birthed New Icons

news

The GRAMMY Museum Celebrates Black History Month 2024 With A Series Of Special Programs And Events

Throughout February, the GRAMMY Museum will celebrate the profound legacy and impact of Black music with workshops, screenings, and intimate conversations.

The celebration isn't over after the 2024 GRAMMYs. In recognition of Black History Month, the GRAMMY Museum proudly honors the indelible impact of Black music on America and the fabric of global pop culture.

This programming is a testament to the rich heritage and profound influence of Black artists, whose creativity and resilience have shaped the foundation of American music. Through a series of thoughtfully curated events — including educational workshops, family programs, special screenings, and intimate conversations — the Museum aims to illuminate the vibrant legacy and ongoing evolution of Black music.

From a workshop on the rhythmic storytelling of hip-hop following its 50th anniversary and the soulful echoes of Bill Withers' classics, to the groundbreaking contributions of James Brown and the visionary reimagination of "The Wiz," these GRAMMY Museum programs encapsulate the enduring legacy and dynamic future of Black music.

The GRAMMY Museum invites audiences to delve into the stories, sounds, and souls that have woven Black music into the tapestry of our shared human experience. Through this journey, the Museum and the Recording Academy honor the artists, visionaries, and pioneers whose talents have forever altered the landscape of music and culture.

Read on for additional information on the GRAMMY Museum's month-long tribute that explores, appreciates and celebrates the invaluable contributions of Black music to our world.

Thurs., Feb. 8

History of Hip-Hop Education Workshop

WHAT: In celebration of the 50 years of hip-hop, this workshop examines the unique evolution of Hip Hop from its origin to where the genre is today. Highlighting the golden age of Hip Hop, this lesson will provide students with a greater understanding of the struggles and triumphs of the genre.

WHEN: 11 a.m. – 12:00 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Sat., Feb. 10

Family Time: Grandma’s Hands

WHAT: Join us for a very special family program celebrating the recently released children’s book Grandma’s Hands based on one of Bill Withers’ most beloved songs. Bill’s wife, Marcia, and daughter, Kori, will participate in a book reading, conversation, audience Q&A, and performance, followed by a book signing. The program is free (4 tickets per household.)

WHEN: 11 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Mon., Feb. 12

Celebrating James Brown: Say It Loud

WHAT: The GRAMMY Museum hosts a special evening on the life and music of the late "Godfather of Soul" James Brown. The program features exclusive clips from A&E's forthcoming documentary James Brown: Say It Loud, produced in association with Polygram Entertainment, Mick Jagger’s Jagged Films and Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s Two One Five Entertainment, followed by a conversation with Director Deborah Riley Draper, superstar Producer Jimmy Jam, and some surprises.

WHEN: 7:30 p.m. – 9:00 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Sat., Feb. 17

Backstage Pass: "The Wiz"

WHAT: Presented in partnership with the African American Film Critics Association, join us for an afternoon spotlighting the famed Broadway Musical, "The Wiz," with the producers and creative team responsible for the Broadway bound reboot. The program will feature a lively conversation, followed by an audience Q&A in the Museum’s Clive Davis Theater, and will be hosted by AAFCA President, Gil Robertson, and GRAMMY Museum Education & Community Engagement Manager, Schyler O’Neal. The program is free (four tickets per household).

WHEN: 1 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Thurs., Feb. 22

History of Hip-Hop Education Workshop

WHAT: In celebration of the 50 years of hip-hop, this workshop examines the unique evolution of Hip Hop from its origin to where the genre is today. Highlighting the golden age of Hip Hop, this lesson will provide students with a greater understanding of the struggles and triumphs of the genre.

WHEN: 11 a.m. – 12:00 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Reel To Reel: A Hip Hop Story

WHAT: In conjunction with the GRAMMY Museum's exhibit, Hip-Hop America: The Mixtape Exhibit, the GRAMMY Museum is thrilled to host a special screening of A Hip Hop Story with a post-screening conversation featuring Affion Crockett to follow.

WHEN: 7:00 p.m. – 9:00 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Sun., Feb. 25

Lunar New Year Celebration

WHAT: Join us for a special program celebrating Lunar New Year as we usher in the Year of the Dragon with a performance by the South Coast Chinese Orchestra. The orchestra is from Orange County and uses both traditional Chinese instruments and western string instruments. It is led by Music Director, Jiangli Yu, Conductor, Bin He, and Executive Director, Yulan Chung. The program will take place in the Clive Davis Theater. This program is made possible by the generous support of Preferred Bank. The program is free (four tickets per household).

WHEN: 1:30 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.

Tues., Feb. 27

A Conversation With Nicole Avant

WHAT: The GRAMMY Museum is thrilled to welcome best-selling author, award-winning film producer, entrepreneur and philanthropist, Ambassador Nicole Avant to the museum’s intimate 200-seat Clive Davis Theater for a conversation moderated by Jimmy Jam about her new memoir Think You’ll Be Happy – Moving Through Grief with Grit, Grace and Gratitude. All ticket buyers will receive a signed copy of the book.

WHEN: 7:30 p.m. – 9:00 p.m.

REGISTER: Click here.