On Aug. 14, 1969, hundreds of thousands of people took over the small town of Bethel, N.Y. to hear the sounds and inspirational words from their favorite artists, including Jimi Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead. Longtime music journalist, then an 18-year-old music fan, Mike Greenblatt was there.

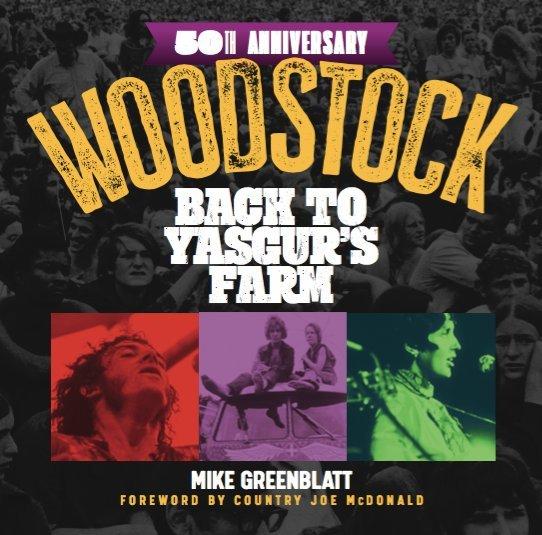

In his brand-new book, Woodstock 50th Anniversary: Back to Yasgur's Farm, out in honor of the fest's 50th anniversary, Greenblatt features his own firsthand account, as well as a collection of submitted stories from both artists and attendees to recreate the experience that transpired a half-century ago—one that original promoter Michael Lang hasn't been able to truly replicate since.

We caught up with Greenblatt over the phone to learn more about what it was really like to be at Woodstock, how we can apply the fest's activist mindset today, which acts blew him away and more.

Photo: Warner Bros/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

How was it for you to revisit Woodstock 50 years later?

I got a lump in my throat a little bit after I revisited that time of me being 18 and being at that particular festival, especially when I started talking to the artists. I did 32 interviews and I read nine books, because a lot of the artists are dead but they have books. And some of the artists would not talk to me. For instance, the guys in Credence Clearwater Revival didn't have very nice things to say about John Fogerty, who refused the band's participation in the movie and the soundtrack. And when I went to go call John Fogerty's people, they said, "He's not talking about that anymore, read his book." So I did.

But it was really a trip back to a much more innocent time and a time that I cherish.

I mean, it was a turning point in your life as a young man, but then also for this country and for so many of the artists that performed. So it's a lot of things coming together.

No doubt about it. It was a turning point for me because it was where I first embarked on the concept of music as salvation. In other words, as long as the music was playing, I was okay. No matter what was going on around me. And we were pretty damn uncomfortable on Sunday. If Thursday, Friday and Saturday were idyllic, Sunday was a disaster. A monsoon whipped through us and all my stuff was back at the car. Tents, clothing, food, pot and water, and we didn't even know where the car was. There was no getting back to the car and we were in T-shirts and shorts and were drenched.

After the rain, it got really cold, even though it was August. Plus, the LSD that I took on Sunday started coming on right when my friend Neil said, "I'm gonna go find a phone booth and call our moms to tell them we're right." Woodstock would have been a lot easier with cell phones and bottled water, let me tell you. He had left and I was alone now and the music stopped. They said, "We're gonna stop the music. There's a storm coming through. Hold on to each other, we'll be right back." So I'm alone, there's no music and it wasn't fun anymore. I started panicking and getting paranoid. And then they made an announcement from the stage, which is in the [1970 Woodstock] movie. They said, "Don't take the brown acid." And I said, "Oh no. I just took it."

"But [Woodstock] was like a cosmic accident."

I would love to hear, in a nutshell, what was it really like to be an attendee, to be part of Woodstock?

I loved Thursday, Friday and Saturday. Saturday night was folk night and there was a light drizzle. People were very friendly and shared their food, water, wine and pot. It was really nice and there was a sense of "we're all in it together," that the long-hair sitting next to you on the grass on the ground was your brother. You knew he was against the war in Vietnam. And you knew he was for civil rights and women's liberation.

And, when Arlo Guthrie held up the newspaper on stage and says that famous line, "The New York State freeway is closed, man," we knew that the whole world was watching. There was a palpable sense of we better not screw it up because we were the peace and love generation. So we couldn't have any problems at this big festival or else it would all go up in flames. And we didn't, that's the whole point about Woodstock. 500,000 people pressed together, wet and cold, hungry and thirsty with not enough food, water and bathrooms and no police. There was no security and there was not one reported instance of violence. How could that be? It's almost impossible to contemplate.

How did the conversations go with the surviving artists whom you interviewed for the book? Does that collective cultural moment still feel like a connective point for you and others who were there?

There is a generational situation going on between the Baby Boomers that we were special, that we were the generation, the dividing point. The artists' backstage revelations were fascinating, and the hard times that they had getting in and out of the festival and the equipment problems that they had. But I think that the interviews that I did with the people that actually ran the show were profoundly revelatory. I did not know, for instance, that governor Rockefeller wanted to send in the National Guard to disperse everybody at the butt of a gun, like Nixon tried to do at Kent State just months later.

Could you imagine? At Woodstock? I mean, the possibility of a disaster was always right there on the surface. But we did it. John Morris is a hero in my eyes. He ran the Fillmore for Bill Graham. Graham lent out his entire staff to Michael Lang for the Woodstock festival because no one had ever heard of Lang and the artists didn't want to commit. Graham vouched for him and the artists rolling in one after another.

But it was like a cosmic accident. Because there wasn't enough facilities. No one, in a million years, expected the people to keep pouring in from all sides and never stop coming. That 500,000 figure is the estimate, of course; there are those who think it was more like 800,000. And professor Chris Langhart from NYU, who is, again, one of the heroes of this festival, says that there's police aerial photos of the area that would almost prove that it was more like 800,000. He said to me, "You going to do a book about Woodstock? You want to get it newsworthy? Call the state police, get them to unleash those records." Well, I tried and it's impossible.

Photo: John Dominis/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Image

The police didn't go into the festival at all, right? It's surprising they decided to stand back.

They let the kids do their thing. The police kept saying how unbelievably well-behaved we were. Max Yasgur, the farmer who let us groove on his property, had to go to bat for us with the townspeople. He's another hero out of this thing. Because we were kicked out of Wallkill and the people that put this thing together, maybe a crew of about 125 people who built the stage and the water system and everything else, they had only 18 days to do the whole thing. And it rained like 15 of those days. It's still the record in Sullivan County, N.Y. for the most amount of rain in a three-week period.

Do you think a Woodstock festival, a.k.a. "three days of peace and music," could authentically be recreated in this day and age?

No. They tried in '94 and '99 and there were arsons, rapes, burglaries and violence. It can't be replicated. It was a one-of-a-kind event, it had never happened before where so many people got together with no violence. It certainly hasn't happened since and I don't think it could ever happen [again] because of human nature. I mean, it was the second-biggest city in New York for those four days. People were born, people died, one guy got run over by a tractor while sleeping in his sleeping bag, one guy had a burst appendix and someone else O.D.ed. That's it, three deaths and a couple of babies were born.

"They tried in '94 and '99 and there were arsons, rapes, burglaries and violence. It can't be replicated. It was a one of a kind event, it had never happened before where so many people got together with no violence."

It's crazy, like you said, to wrap your head around.

Well, we knew it at the time and we were in it. It was like everything that we had read about, heard about on the radio, watched on TV and the bands that we tried to see at [Madison Square] Garden and at clubs in New York. We would get so excited to see one band we loved. This was all our bands at the same place, at the same time. And watching this taboo of humanity, especially after the rains came on Sunday, where people that I would be scared to meet on a dark corner in Newark, N.J., where I was raised, were making fires and feeding people and handing out blankets, and the townspeople showed up in flatbed trucks handing out bread. To be in it and look at it and be heavily tripping at the time just made it phantasmagoric, surrealistic.

I knew it was so special, but I could only just stand there and look at it. I wasn't one of the people that would take charge in helping other people, I admit. I stood there and I looked all around me, fascinated.

How did being an attendee at Woodstock affect your path in life? I know you ended up going into music writing. How do you see that now, looking back?

My mother cried and cried when I came home, she had seen the news. I end the book with her tears as a metaphor for the older generation trying to understand us. But I think that was the moment I realized that's what I wanted to do. I wanted to listen to more music and tell people about it. The fastest way to do that was to go to shows and write about it, and that's all I've ever done, listen to music and tell people about it, be it as a journalist, an editor or a publicist. Ever since Woodstock, that was my mission in life. And it persists to this day.

Woodstock feels like a great early example of how gathering a large group people around music can really make waves in society. What are your beliefs or your thoughts on the power of music to create change?

Music is spiritual. People to listen to music and get from it what they will, but it's all about that connection between the human and the sounds. And there's something about lyrics and chords, melodies and harmonies and instrumentation, that when put together in the proper way, have a profoundly—it's religious to me. I consider myself agnostic, but music is my religion and my church. When I go to a show and the show is absolutely perfect, I'm in church, man.

I can relate to that. And for religious ceremonies, music is the part that moves people.

At the very beginning of time, all music was religious music.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/AqZceAQSJvc" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

What do you think performing Woodstock meant to each of these artists?

There's 32 different answers to that question, 32 different artists. Quill, for instance, was supposed to be the band that broke big after Woodstock. To me, they sounded like a bunch of guys banging on pots. Santana that became superstars after. The Santana album wasn't even out yet, nobody knew who they were.

Santana came out, people were enjoying themselves on a sunny day at the time, and their performance was so incendiary and so righteous, fusing unbelievably great hard rock with salsa music, no one had ever heard anything like that. They practically invented world beat music right on that very stage. And Michael Shreve's drum solo during "Soul Sacrifice" that day [pauses]—he was barely 20. It galvanized the entire Woodstock nation and they became superstars.

Now, that's just 1 of 32. And for my favorite, there's a few. There were bands that carried me away; The Band, for instance. Back then, we thought a band was great by how close to the record they sounded. The Band sounded exactly like their records, the vocals, the harmonies. And they kept switching instruments. They all played every instrument, Switching after every song, I have never seen that. So they stand out.

Sly and the Family Stone also stand out. Because it was so late, I was falling asleep and their set was so rabble-rousing. We were up on our feet and chanting, "Higher, higher!" during the song "I Want To Take You Higher." Sly Stone was at the top of his game and the band was unbelievable. And Mountain—Leslie West's lead guitar—was the loudest band I ever heard in my life. They practically invented heavy metal at Woodstock. There's so many others I can think of.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Blz_sef-jj4" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

I think that's part of what's interesting with "hard questions" like this, of how we summarize these major things. And to see, 50 years later, what still stands in the front of your mind.

One thing that stands in front of my mind was Friday night, the very last performer was Joan Baez. She was very pregnant, and she came out and had a political agenda. Politics was a subtext of Woodstock, with Vietnam and Nixon. She sang "Joe Hill," the story of this union martyr who said, when they executed him for a murder he didn't commit, "Don't mourn, organize." That still sends chills through my rather leftwing, liberal body. Joan Baez was so affecting to us, when she sang "We Will Overcome." It wasn't corny back then, it was real. And she sang [the Byrds'] "Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man" with a friend that she brought out, and they referenced Ronald Reagan, who everybody already hated as the governor of California.

"Get behind the people that you like politically and go out and volunteer. Do something. Work with the homeless, work with the disenfranchised. And don't just complain about things, get involved. You can change the world."

Santana said in a recent interview about Woodstock, "The people wanted the same things we want today." That really stuck with me because it's true; women and people of color are still not treated equally and we're still fighting wars abroad. So, what message do you have for young people today who are unhappy with the current state of affairs? What are your takeaways from the Summer of '69 and how do you think they apply today?

Well, just like Joe Hill said, "Don't mourn, organize." All politics is local, it all starts on a local level. If you're outraged at what's going on today, get involved, go door to door, take names. It's what I did this past year, in 2018, for a local woman who had never run for anything. I mean, she lost, but she made a point. Get behind the people that you like politically and go out and volunteer. Do something. Work with the homeless, work with the disenfranchised. And don't just complain about things, get involved. You can change the world.

That was the whole thing about the '60s. We really thought we were going to change the world. Well, guess what? We didn't, but that feeling, it's a feeling of camaraderie with your fellow hippie back at the time. Find like-minded people and get together and organize and fight to change what's going on today. It's almost worse now than it was in '69. I hate to say that.

I think, like you said, everyone at Woodstock knew the world was looking and that it was important to show what peace and love really meant.

Exactly. We proved it at Woodstock.

It speaks to the power of people speaking up and using the platforms of music, of festivals, of peaceful organized groups to show that love is indeed stronger.

Well, I thought when I was 16, when The Beatles sang "All You Need Is Love," I actually believed that. Of course it was naïve, you need a hell of a lot more than love. But it's a good starting point.

What do you believe, in the couple of months and years following Woodstock, were the biggest after-effects? What happened when you all came home?

The iconic nature of the festival really didn't manifest itself until much later. The movie came out in 1970, which was a year later, and all of the sudden people started getting interested in Woodstock again. It was a wonderful movie, it revolutionized cinema with the split screen effects and so forth. It hadn't been done at that time. After the movie came out, there was a rush of Woodstock appreciation. But then, in the mid- to late-'70s, when punk rock took hold and rock stars became passé, Woodstock became almost trivialized. It almost wasn't appreciated for what it was. I don't know when the tide turned again, but now it is really looked upon as something special. There's the great Woodstock museum up at Bethel Woods, which is on the site of the actual festival, where I'll be for three days, starting August 15.

This is the last gasp of Woodstock, man. It's not going to have this much attention for the 51st, the 52nd; the 50th, this is it. This is our Woodstock swan song. But people should remember that for four days, the peace and love generation proved its point with no police and a half a million people in horrible conditions. No violence, that's the important thing.

I didn't know that before I read your book. I feel like it's not something that always gets highlighted about the event.

Well, there was a lot of things in the book that people are telling me that they read for the first time. I was edited a little bit, I was censored a little bit, probably rightfully so. That said, this is not a book for the whole family. The drugs were prevalent, sure, but my editor took out so many references and I said, "Why are you taking out drugs? This is sex, drugs and rock and roll." He goes, "Yeah, but on every page?" It was just a different time, be it sex, be it drugs.

There's a lot of written material about Woodstock out there. Why should people read your book?

Because I was there. I don't know how many books are coming out about Woodstock this summer, there's going to be a ton of them. But how many authors did the brown acid and can give you a firsthand [account]? I did, as I say, 32 interviews, read nine books, plus my own experiences. It's a tapestry, it's a mosaic of all those different perspectives.

Why Can't Anyone Get Woodstock Right? 15 Of The Original Fest's Performers Weigh In