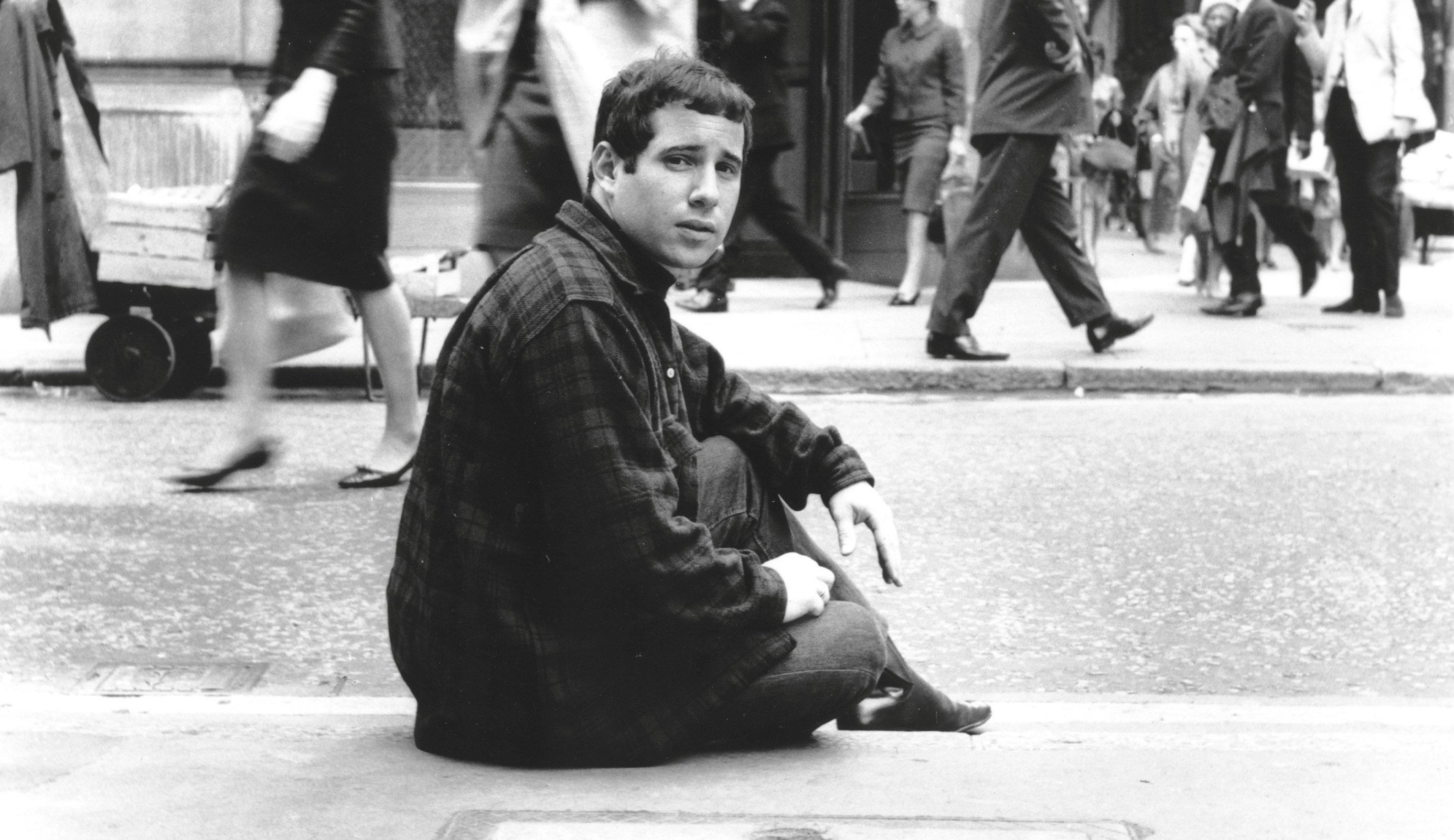

Photo: Chris Walter / Contributor

feature

Joni Mitchell's Performance At Newport Folk 2022 Was Monumental. But Let's Not Forget Paul Simon Singing "The Sound of Silence."

Joni Mitchell's weathered performance of her 1960s classic "Both Sides, Now" at the festival was a historic moment. But Paul Simon singing "The Sound of Silence" was just as major — and invites a fresh examination of his legacy.

Of all the surprise guests at Newport Folk 2022, Joni Mitchell got the most ink. And that's not only to be expected; it's richly deserved.

Here's a woman who started out by blowing Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's minds to smithereens, reinvented herself five or six times like Miles Davis, played some of the furthest-out guitar anybody ever heard and wrote a handful of songs that can be genuinely considered perfect. (Looking at you, "Both Sides Now" — and not just because CODA kicked the classic back into the mainstream.)

Plus, she won nine GRAMMYs and was nominated for 17 — and was MusiCares' Person Of The Year in 2022, received with a lavish gala and star-studded, pre-GRAMMYs tribute concert.

And after everything, that the childhood polio survivor pulled through a 2015 brain aneurysm, retaught herself to play guitar, and stood at Newport Folk 2022 singing a few of those perfect songs with her adoring collaborators is something like proof of the existence of miracles.

But while any discussion of the surprises at Newport will naturally begin with Mitchell, it's tended to obfuscate another transformative moment from the weekend: Paul Simon stepping out of semi-retirement to sing "Graceland," "American Tune" and "The Boxer" with an assortment of famous friends, among them Nathaniel Rateliff and the Night Sweats.

Simon's appearance went theoretically toe-to-toe in importance with Mitchell's — he ended his set with a spine-chilling, solo performance of "The Sound of Silence." Much like Mitchell's tune, he wrote it young — and it's developed majestic new dimensions across the decades.

Why might some receive Simon's appearance with less fanfare than Mitchell's — aside from her challenges and attendant time off? It's worth examining Simon's place in the contemporary music world — and his critical cachet within.

Despite winning 16 GRAMMYs, being nominated for 35, receiving a lavish GRAMMY Salute tribute concert in 2022and never making a bad album, a couple of narratives of questionable practices have followed him around — both of them regarding his 1986 masterpiece, Graceland.

Framing Simon Today

The first regarded his violation of the international boycott against South Africa regarding their vile apartheid policies — a picket line Simon crossed not because he sided with the oppressors, but because he believed nobody should stop him from collaborating with musicians he loved and respected.

"I knew I would be criticized if I went, even though I wasn't going to record for the government of Pretoria or to perform for segregated audiences," Simon told the New York Times in 1986. "I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired."

As Simon added, he consulted with Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte about it, due to their deep ties to the South African musical community; both men gave Simon their blessing. This didn't come close to extinguishing the firestorm, though; even Linda Ronstadt received blowback for merely appearing on it.

The second asterisk on his legacy comes from his supposed treatment of Los Lobos, from whom he's been said to have stolen the Graceland track "All Around the World or the Myth of Fingerprints." The veracity of this story mostly comes from Los Lobos member Steve Berlin's eyewitness account.

As Berlin alleged to Rock Cellar, during the sessions, "Rather than engage us, Paul would just stare at us like we were animals in a zoo or something." And when his ears pricked up at a composition Los Lobos were working on, Simon asked if he could build on it. Which meant the Chicano rockers were shocked at the ensuing record-sleeve credits: "Words and Music by Paul Simon."

"We're asking and asking, then finally six months later we hear from Paul and he says, 'Sue me. See what happens.'" Berlin continued. "That's a direct quote, so that gives you an indication of what kind of guy he is."

These kinds of stories don't follow around Mitchell, whose standing has only exploded in scale with no sign of letting up. This is not only for her incredible musical accomplishments, but also for giving a generation of confessional singer/songwriters — many of them women — a voice, mainly with her watershed album Blue.

But still, Simon is correctly viewed as an innovator, a wordsmith and a titan — part of which has been kicked up by the reaction to a provocative op-ed.

"Simon's Descendents"

In 2021, Simon was thrust back in the conversation thanks to a piece in NBC News THINK, framing Simon's decision to sell his catalog for $250 million as a futile attempt to be remembered centuries after his death.

"[Neil] Young and Joni Mitchell and Bruce Springsteen and, of course, Paul Simon — all giants in their day — will be no more than footnotes, at best, to Dylan and the Beatles," writer Jeff Slate declared. This prognostication inspired explosive debate; YouTube giant Rick Beato spent an entire episode skewering Slate, and John Mayer decidedly planted his flag on Simon's side.

"I'm one of Simon's descendents," the seven-time GRAMMY winner wrote on Instagram. "And for as long as I live I will make sure he's never forgotten."

And it was that same animating force that led Nathaniel Rateliff and the Night Sweats to throw an entire "American Tune Revue" at Newport Folk 2022, with everyone from Natalie Merchant to Lukas Nelson to the Silk Road Ensemble present to enshrine him in the Tower of Song.

So, that's more or less where Simon sits these days — which is to say nothing of the millions who continue to revere his songbook. But, back to "The Sound of Silence": Why did it matter when he wrote it, and why were rapt audience members reduced to tears when he sang the song at Newport?

A Vision Softly Creeping

Imagine a 21-year-old Simon, softly fingerpicking an acoustic guitar in the reverberating bathroom of his family's Queens home. He had a spectral melody in mind, but the words hadn't come yet.

But when John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November of 1963 — just over a month after Simon's 22nd birthday — a line came to his lips, staggering in its power and simplicity. "Hello, darkness, my old friend," he sings. "I've come to talk with you again."

Does the rest of the song live up to that monumental opener? That's up for debate, but the lines that spill forth still pack a poetic radiance, from Gospels-like blasts of light to scrawled prophecies in tenement halls. But it ultimately curls in on itself — silence, and the shadow, conquer all.

It was the electrified, Byrdsy arrangement of the song that landed Simon and Garfunkel a deal with Columbia Records, became a monster hit and ultimately laid the groundwork for Simon's entire legacy. But the stripped-down version on the Old Friends boxed set is the one to cherish, illuminating the pair's otherworldly harmonies and Simon's spooky, fingerpicked voicings.

When things grow unremittingly glum — which has never stopped happening since 1963 — "The Sound of Silence" still feels like a fitting companion. The tune's cinematic legacy alone is worthy of its own article, from driving home The Graduate's theme of ennui and disconnectedness to augmenting the despair of a rainy graveyard scene in Watchmen.

And back in the real world, Simon performed "The Sound of Silence" on Ground Zero on the 10th anniversary of 9/11 — an unspeakable slaughter that had transpired just a few subway stops away from his apartment.

A few years later, one of the most public and resonant 21st-century usages of "The Sound of Silence" came by way of Disturbed — if you think the nu-metallers aren't for you, you still need to behold this magisterial cover.

They performed it on Conan while singer David Draiman was literally down with the sickness; his vocal, in equal parts honeyed and thunderous, still spurred YouTube commenters to request it at their funeral. And in life, many commented, they sought solace in that performance when grief or pain or abandonment felt insurmountable.

Disturbed received the most tremendous honor possible: an approving email from Simon himself. "Really powerful performance on Conan the other day. First time I'd seen you do it live. Nice. Thanks," he wrote. "Mr. Simon, I am honored beyond words," Draiman responded. "We only hoped to pay homage and honor to the brilliance of one of the greatest songwriters of all time."

So that's why it was so moving to watch an 80-year-old Simon strip "The Sound of Silence" to its essence — murmuring the lyrics sans Garfunkel as thousands watched awestruck, while the sun set in pastel hues over the Atlantic Ocean. Because we've all had a long sit with Death for private communion.

But when it's tempting to abandon the light and go the other way, "The Sound of Silence" helps us refuse to give up hope. That's the ultimate power of a song, delivered by one of the greatest to ever pick up a guitar and a pen.

And much like Mitchell of his generation, we must all be grateful to be able to sit at Simon's feet, open our hearts and minds, and listen. And right then: the silence is shattered.

Béla Fleck Has Always Been Told He's The Best. But To Him, There Is No Best.

Photo: Ebru Yildiz

list

Who Is Rhiannon Giddens? 3 Things To Know About The Banjoist & Violist On Beyoncé’s "Texas Hold ‘Em"

Rhiannon Giddens has been esteemed in various folk circles for years — and her appearance on Beyoncé’s "TEXAS HOLD ‘EM" just broke her into the mainstream. Here are three things to know about the eclectic singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist.

After the club-storming Renaissance, its Act II begins with an unexpected sound: a burble of banjo, later joined by flowing viola. Welcome to "TEXAS HOLD ‘EM," one of two advance singles from Beyoncé’s forthcoming album, along with "16 CARRIAGES."

Beyoncé’s recently announced Act II promises to be an immersion into country music — which is both a fresh aesthetic and one deeply rooted to her Texan upbringing. The 32-time GRAMMY Winner has spoken about the "overlooked history of the American Black cowboy" and nodded to the culture with a Western getup at the 2024 GRAMMYs.

All of this is a completely natural fit for Rhiannon Giddens, who played said fiddle and viola on "TEXAS HOLD ‘EM."

"The beginning is a solo riff on my minstrel banjo — and my only hope is that it might lead a few more intrepid folks into the exciting history of the banjo," Giddens explained on Instagram. "I used to say many times as soon as Beyoncé puts the banjo on a track my job is done.

"Well, I didn’t expect the banjo to be mine," she continued. "And I know darn well my job isn’t done, but today is a pretty good day."

The "job" defines Giddens. Sure, she may be completely new to certain contingents of the Beyhive, but the two-time GRAMMY winner and 10-time nominee’s been on the scene for almost two decades.

Since making her mark with the Carolina Chocolate Drops in the mid-aughts, Giddens has forged a singular legacy. She’s not only a purveyor of traditional musics, but as an investigator of the racial and cultural cross-currents that forged our modern-day understanding — and misunderstanding — of Americana.

At the 2024 GRAMMYs, Giddons was nominated for two golden gramophones — for Best Americana Album (You’re the One) and Best American Roots Performance ("You Louisiana Man"). You’re the One was her first album of all-original material; in that regard, these noms show that a new, exciting chapter for Giddens is just beginning.

Here are five things to know about the artist who just played "TEXAS HOLD ‘EM" with Queen Bee.

Her Interrogation Of Black Music History Is Indispensable

Giddens has worked in a diverse array of fields, including opera, documentary, ballet, podcasting, and more. Her mission? To explore "difficult and unknown chapters of American history" through musical lenses, like the evolution of the banjo from Africa to Appalachia.

"In order to understand the history of the banjo, and the history of bluegrass music, we need to move beyond the narrative we've inherited," she’s stated. Elsewhere, she noted, "People seem ready for a more in-depth idea of folk music, culture and history.

Which extends beyond merely other people’s stories — but to her own.

…And It Led Directly To You’re The One

Speaking to GRAMMY.com about her GRAMMY-nominated first album of original material, Giddens was quick to note that "autobiography" doesn’t hit the mark.

"It doesn't express how I feel… they're still songs, and it's still a performance," Giddens said. "I'd say I'm drawing a little bit more from my experience, but I had to draw from my experience to write other people's stories.

"There's emotions that I feel that I then translate into these other stories," she added, "so I don't think this record is completely different from that."

She’s Made Killer Appearances With Paul Simon

Paul Simon’s ended his touring years, but he does make sporadic appearances, including at 2022’s "Homeward Bound: A GRAMMY Salute to the Songs of Paul Simon."

There, they performed a version of his epochal "American Tune," where he changed the words in nuanced ways as relates to the American origin story — and he enlisted Giddens to sing it with him.

"He didn't have to do nothing but sit back and collect his checks," Giddens told GRAMMY.com. "He made a statement with that song, and I don't want to take that away from him. I didn't change those words; he changed those words."

Where will Giddens go from her star turn with Bey? Wherever it might be, we’ll feel — and learn — something profound, one banjo strum at a time.

On You’re The One, Rhiannon Giddens’ Craft Finds A Natural Outgrowth: Songwriting

Photo: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

feature

How The 2024 GRAMMYs Saw The Return Of Music Heroes & Birthed New Icons

Between an emotional first-time performance from Joni Mitchell and a slew of major first-time winners like Karol G and Victoria Monét, the 2024 GRAMMYs were unforgettably special. Revisit all of the ways both legends and rising stars were honored.

After Dua Lipa kicked off the 2024 GRAMMYs with an awe-inspiring medley of her two new songs, country star Luke Combs followed with a performance that spawned one of the most memorable moments of the night — and one that exemplified the magic of the 66th GRAMMY Awards.

Combs was joined by Tracy Chapman, whose return to the stage marked her first public performance in 15 years. The two teamed up for her GRAMMY-winning hit "Fast Car," which earned another GRAMMY nomination this year thanks to Combs' true-to-form cover that was up for Best Country Solo Performance. The audience went wild upon seeing a resplendent, smiling Chapman strum her guitar, and it was evident that Combs felt the same excitement singing along beside her.

Chapman and Combs' duet was a powerful display of what the 2024 GRAMMYs offered: veteran musicians being honored and new stars being born.

Another celebrated musician who made a triumphant return was Joni Mitchell. Though the folk icon had won 10 GRAMMYs to date — including one for Best Folk Album at this year's Premiere Ceremony — she had never performed on the GRAMMYs stage until the 2024 GRAMMYs. Backed by a band that included Brandi Carlile, Allison Russell, Blake Mills, Jacob Collier, and other accomplished musicians, the 80-year-old singer/songwriter delivered a stirring (and tear-inducing) rendition of her classic song "Both Sides Now," singing from an ornate chair that added an element of regality.

Later in the show, Billy Joel, the legendary rock star who began his GRAMMY career in 1979 when "Just the Way You Are" won Record and Song Of The Year, used the evening to publicly debut his first single in 17 years, "Turn the Lights Back On." (He also closed out the show with his 1980 classic, "You May Be Right.") It was the latest event in Joel's long history at the show; past performances range from a 1994 rendition of "River of Dreams" to a 2022 duet of "New York State of Mind" with Tony Bennett. The crooner, who died in 2023, was featured in the telecast's In Memoriam section, where Stevie Wonder dueted with archival footage of Bennett. And Annie Lennox, currently in semi-retirement, paid tribute to Sinéad O'Connor, singing "Nothing Compares 2 You" and calling for peace.

Career-peak stars also furthered their own legends, none more so than Taylor Swift. The pop star made history at the 2024 GRAMMYs, claiming the record for most Album Of The Year wins by a single artist. The historic moment also marked another icon's return, as Celine Dion made an ovation-prompting surprise appearance to present the award. (Earlier in the night, Swift also won Best Pop Vocal Album for Midnights, announcing a new album in her acceptance speech. To date, Swift has 14 GRAMMYs and 52 nominations.)

24-time GRAMMY winner Jay-Z expanded his dominance by taking home the Dr. Dre Global Impact Award, which he accepted alongside daughter Blue Ivy. And just before Miley Cyrus took the stage to perform "Flowers," the smash single helped the pop star earn her first-ever GRAMMY, which also later nabbed Record Of The Year.

Alongside the longtime and current legends, brand-new talents emerged as well. Victoria Monét took home two GRAMMYs before triumphing in the Best New Artist category, delivering a tearful speech in which she looked back on 15 years working her way up through the industry. Last year's Best New Artist winner, Samara Joy, continued to show her promise in the jazz world, as she won Best Jazz Performance for "Tight"; she's now 3 for 3, after also taking home Best Jazz Vocal Album for Linger Awhile last year.

First-time nominee Tyla became a first-time winner — and surprised everyone, including herself — when the South African starlet won the first-ever Best African Music Performance GRAMMY for her hit "Water." boygenius, Karol G and Lainey Wilson were among the many other first-time GRAMMY winners that capped off major years with a golden gramophone (or three, in boygenius' case).

All throughout GRAMMY Week 2024, rising and emerging artists were even more of a theme in the lead-up to the show. GRAMMY House 2024 hosted performances from future stars, including Teezo Touchdown and Tiana Major9 at the Beats and Blooms Emerging Artist Showcase and Blaqbonez and Romy at the #GRAMMYsNextGen Party.

Gatherings such as A Celebration of Women in the Mix, Academy Proud: Celebrating LGBTQIA+ Voices, and the Growing Wild Independent Music Community Panel showcased traditionally marginalized voices and communities, while Halle Bailey delivered a GRAMMY U Masterclass for aspiring artists. And Clive Davis hosted his Pre-2024 GRAMMYs Gala, where stars new and old mingled ahead of the main event.

From established, veteran artists to aspiring up-and-comers, the 2024 GRAMMYs were a night of gold and glory that honored the breadth of talent and creativity throughout the music industry, perfectly exemplifying the Recording Academy's goal to "honor music's past while investing in its future." If this year's proceedings were any indication, the future of the music industry is bright indeed.

news

I Was A Trophy Holder At The 2024 GRAMMYs Premiere Ceremony

During the 66th GRAMMY Awards Premiere Ceremony, four GRAMMY U Representatives presented golden gramophones to Billie Eilish, boygenius, Tyla, and others. Read on to learn how GRAMMY U Reps were able to grace the stage on Music's Biggest Night.

From lighting technicians to audio engineers to writers, hundreds of people make the GRAMMYs possible. Whether these professionals are on stage or working behind the curtain, all of these vital roles help produce Music’s Biggest Night.

Another vital role on GRAMMY night is that of trophy holder, where one is tasked with bringing out the physical golden gramphones and winner envelopes to presenters. Trophy holders then usher the award recipient off the stage after their speech. Representatives from GRAMMY U’s Atlanta (Jasmine Gordon), Texas (Pierson Livingston), Pacific Northwest (Chloe Sarmiento), and Chicago (Rachel Owen) Chapters were selected to be trophy holders at the 2024 GRAMMYs Premiere Ceremony, and went behind the scenes.

The real preparation actually commences before the show lands on screens back home. Prior to GRAMMY Sunday, the four representatives visited the Peacock Theater to get the rundown on stage positions, proper handling of the GRAMMY Award, proper attire for the event, and various other subtle details that would normally go unnoticed.

On the day of the show, trophy holders arrived for their 10 a.m. call time, receiving a final rehearsal of the show with the backing music and stage lights. Post-rehearsal, they headed into hair and makeup for final touch-ups to become camera-ready. From then, focus shifts to getting into place and calming restless nerves before the show kicks off at noon.

"At first there were so many nerves taking over my body," said Jasmine Gordon, Atlanta Chapter Rep. "But, as soon as I walked on stage there was a rush of excitement and happiness that took over."

This year, following an opening performance from Pentatonix, Jordin Sparks, Larkin Poe, J. Ivy, and Sheila E., host Justin Tranter introduced the GRAMMY U Representatives as they lined up on the stage. From there, the show commenced and winners were announced.

Before trophy holders take the stage, the envelopes are meticulously triple-checked to make sure they are representing the right category and a GRAMMY is placed in their hands. The envelope is given to the presenter to announce the winner.

As the audience applauds and the winner makes their way to the stage from their seat, the presenter trades the envelope for the golden gramophone which they give to the winner. While the trophy holder typically stands in the shadows to the side of a presenter like Jimmy Jam or Natalia Lafourcade, they occupy a very important and visible place on the GRAMMY stage.

After an approximately 45-second acceptance speech, trophy holders escort the winner backstage for photos and media. The trophy holders rinsed and repeated that routine dozens of times,handing off golden gramophones and escorting artists such as Billie Eilish, boygenius, and Tyla.

Chicago GRAMMY U Rep Rachel Owen shared that one of her favorite moments included being on the side stage, standing right next to music icon Joni Mitchell when she won the GRAMMY for Best Folk Album.

"I’ll never ever forget the moment Joni Mitchell won for Best Folk Album. Everyone was cheering her on and she just got so happy, I feel so lucky to have witnessed that moment," Owen says. "I hadn’t realized before how close I would be to the winners; it was a great surprise."

Reflecting on the ceremony, the GRAMMY U Representatives shared how surreal the entire experience was for them and their professional development.

"Being right with artists as they win or right after they won was such a surreal experience," says Owen. "The overwhelming joy I got to witness from so many artists was contagious, I simply had an amazing time."

Photo by Johnny Nunez/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

news

9 Ways Women Dominated The 2024 GRAMMYs

From Taylor Swift and Tyla's historic wins, to Miley Cyrus' first GRAMMYs and Joni Mitchell's first performance, the 66th GRAMMY Awards put ladies first.

Women shined particularly bright at Music's Biggest Night this year. As Trevor Noah put it in his monologue: "There’s a band that has already won today called boygenius, it’s three women. That’s how good a year it is for women."

Beyond boygenius' first GRAMMY wins, the conversation about female artists' legacy at the 2024 GRAMMYs had been building since the nominations were announced, when it was revealed that seven of the eight nominees for Album Of The Year were women. The majority of the performers for the 66th GRAMMY Awards were also women, including the legendary Joni Mitchell, Billie Eilish, SZA, and Dua Lipa. And several female artists were on the precipice of making history (chief among them, Taylor Swift, who later became the first ever four-time winner of Album Of The Year.

The results of the ceremony were no less centered on the ladies. At the Premiere Ceremony, Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus won three of the six Rock Categories for their work as boygenius. Lainey Wilson nabbed Best Country Album, Joni Mitchell won Best Folk Album, and Victoria Monét won Best R&B Album and Best New Artist. Gaby Moreno, Karol G and Tyla nabbed trophies as well.

As the night went on, that tally continued. In fact, other than Producer Of The Year and Songwriter Of Year, a woman won every category in the General Field, including Billie Eilish's "What Was I Made For?" winning Song of the Year and Taylor Swift's Midnights pulling off the big fourth Album Of The Year win.

From every corner of the room, Music’s Biggest Night was filled with powerful women taking the spotlight. Here are eight moments where women ruled the 2024 GRAMMYs — with no sign of this reign ending.

Taylor Swift Hits Lucky Number 13 (And 14, Too)

While it’s true that Taylor Swift’s name has been at the center of what feels like 98 percent of music in the past year, and that continued at the 2024 GRAMMYs. Much speculation ahead of the 66th GRAMMY Awards came down to whether she would make history by winning her fourth Album Of The Year award.

Adding to the excitement, the iconic Celine Dion surprised the world and took the stage to announce the winner for the night’s final award, and it happened: "Taylor Swift."

Rather than bask in her own glory, Swift seemed shocked, fumbling to get a high-five and hug connected with close friend and uber-producer Jack Antonoff. And her acceptance speech made it clear that while she appreciated and was honored by the award, she wasn’t about to rest on any laurels, no matter how massive they may be.

"I would love to tell you that this is the best moment of my life, but I feel this happy when I finish a song, or when I crack the code to a bridge I love, or when I'm shot-listing a music video, or when I'm rehearsing with my dancers or my band, or getting ready to go to Tokyo to play a show," she said. "For me the award is the work. All I wanna do is keep being able to do this. I love it so much, it makes me so happy."

True to that word, the evening also featured Swift announcing a new album — after Midnights won Best Pop Vocal Album (her lucky number 13th GRAMMY) earlier in the night, Swift made the surprise announcement that she’d be releasing her 11th studio album, The Tortured Poets Department, on April 19.

There was something inspiring, too, about the way Swift got to the stage — practically yanking Lana Del Rey from her seat at the same table, demanding she join her onstage. "I think so many female artists would not be where they are and would not have the inspiration they have if it weren’t for the work that she’s done," Swift told the assembly. "She’s a legacy artist, a legend in her prime right now."

Always a booster of other women in the industry, of course she had to share the spotlight even with her history-making fourth Album Of The Year award in hand.

Tracy Chapman Returns To The GRAMMY Stage

Sure, it was Luke Combs nominated for Best Country Solo Performance, but he made it crystal clear that he was there because of Tracy Chapman.

"That was my favorite song before I even knew what a favorite song was," he said in a video package prior to his performance, evocatively describing trips in his dad’s pickup truck, Chapman’s self-titled debut on the cassette player. Combs loved the song so much, he explained, that he wanted to put a cover of it on his 2023 album, Gettin' Old.

He went on to laud its universal appeal, the way Chapman’s chorus gets full-throated sing-alongs no matter the listener’s background — a powerful message, considering that Combs’ recording winning the Country Music Awards' Song Of The Year award made Chapman the first Black woman to receive that honor. "To be associated with her in any way is super humbling for me," Combs said.

The show transitioned from that heartfelt praise directly to Chapman’s hand on her guitar neck, picking out that iconic acoustic riff. Thirty-five years after its initial release, there was Chapman again on the GRAMMYs stage, this time dueting with a country star clearly in awe of sharing her space, mouthing along with the lines he wasn’t singing. It was an unforgettable performance, astonishing in its ability to pull us all out of our bodies and into the spirit of music.

The Endless Allure Of SZA

"Nobody got more nominations this year than SZA," Trevor Noah announced during his opening monologue — and that was after the experimental R&B artist born Solana Rowe had already won two GRAMMYs at the Premiere Ceremony earlier in the evening.

SZA had many more special moments left in the night. She performed a section of the GRAMMY-nominated "Snooze" in a black trenchcoat and hat, and the blade-wielding rebuke triggered the transition to another smash hit from 2022’s SOS: "Kill Bill". The cinematic performance featured a squad of leather-clad woman assassins slicing and dicing a series of men in suits, as SZA effortlessly walked the stage to deliver the world’s sweetest anthem centered on homicide. (For the record, the sight of Phoebe Bridgers’ outright glee at the sight of a sword-wielding dancer standing on her table at the song’s outset has to go down as one of the night’s best moments.)

Later, she would take home the GRAMMY for Best R&B Song for "Snooze" — her tally of three awards tying for the second largest of any artist at the 66th GRAMMY Awards. SZA was handed the golden gramophone by Lizzo, the two women clearly sharing a special moment.

"Lizzo and I have been friends since 2013 when we were both on a tiny Red Bull tour, opening up in small rooms for like 100 people. And to be on the stage with her is so amazing, I’m so grateful," SZA said after sprinting onstage, having just changed out of her performance attire. The tearful, brief acceptance speech that followed showed the incredibly honest and passionate person — and performer — that she is.

Boygenius Win Their First GRAMMY Awards

For a trio of badasses like boygenius, one or two GRAMMYs just wouldn’t do. They needed an award apiece: Best Rock Performance, Best Alternative Music Album, and Best Rock Song (all handed to them by queer icon Rufus Wainwright, no less). Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus sprinted down the aisle in their matching white suits at the Premiere Ceremony, giddy, shocked, together.

Befitting the trio’s history — both together and separately — as brilliant writers and lyricists, each had their own memorable line.

"Music saved my life. Everyone can be in a band, this band is my family," Baker said, beaming after they won the Best Rock Performance award. "We were all delusional enough as kids to think that this might happen to us one day," Dacus said with a laugh. But just two days after the public announcement that the band was going on hiatus to focus on their own solo projects, it was this quick aside from Bridgers during their acceptance for Best Rock Song that brought the warmth: "I owe these boys everything. I love you guys so much."

Tyla Makes Africa Proud

Trevor Noah may have been the host, but he wasn't the only one bringing South African flavor to the 2024 GRAMMYs.

"What the heck!?" Tyla said earlier in the evening at the Premiere Ceremony, grinning as her Johannesburg accent dripping with gleeful shock. At just 22 years old and a month out from even releasing her debut studio album, the viral pop star was nominated in the stacked inaugural Category of Best African Music Performance, including Asake & Olamide, Burna Boy, Davido and Musa Keys, and Ayra Starr. But it was Tyla’s "Water" — an amapiano-driven pop instant classic — that took home the award.

The song had already made history, as the first South African single to reach the Billboard Hot 100 since jazz legend Hugh Masekela achieved that feat in 1968, not to mention that the song reaching number seven made Tyla the highest-charting African female solo musician in Billboard history.

"If you don’t know me, my name is Tyla, I’m from South Africa, and last year God decided to change my whole life," she said, the glow of the GRAMMY gold radiating on her face.

Annie Lennox Knows We Are Never Forgotten

The In Memoriam segment inevitably provides some of the most touching moments of any GRAMMY Awards. But every once in a while, a truly special performance will stand out amidst the heartache. Such was the case with Annie Lenox’s tear-stained performance of "Nothing Compares 2 U" from the late Sinéad O’Connor. The Eurythmics vocalist sat piano-side, a tear-like streak of glitter applied below her left eye, delivering the Irish legend’s best-loved song with every ounce of gravitas the moment demanded — and then some.

"Nothing compares/ Nothing compares to you," she sang with her eyes gazing skyward, before clenching them tight, her lips quivering. And as the song rounded to a finish, Lenox raised a fist, and spoke a simple, direct sentence that the outspoken activist O'Connor surely would have appreciated: "Artists for ceasefire, peace in the world."

Joni Mitchell Proves It's Never Too Late For Firsts

When word got out that Joni Mitchell would be making her first performance at the GRAMMYs, the global anticipation for the ceremony seemed to hit a boiling point. Since recovering from a brain aneurysm in 2015, Mitchell has been stepping into the spotlight more in recent years, but the thought of her onstage at the 66th GRAMMY Awards still felt miraculous.

But then there was Brandi Carlile, extolling Mitchell’s many virtues before introducing one of the greatest singer-songwriters of all time. "Joni just turned 80 my friends, but we all know she’s timeless," Carlile smiled, noting as well that "the matriarch of imagination" had already won a GRAMMY that same evening for Best Folk Album.

And then the lights came up on Joni, seated in a gold-framed armchair, clutching a cane with a silver cat’s head on its hilt, singing the first lines of the all-time classic "Both Sides Now." Backed by a band of GRAMMY-winning heroes in their own right (Carlile, along with SistaStrings, Blake Mills, Lucius, Allison Russell, and Jacob Collier), it seems impossible that any eye in the room could have remained dry, let alone focused anywhere except right on Mitchell, with her beating heart and sky-scraping lyricism. Even Carlile, seated at her left, couldn’t stop looking up from her guitar to smile in awe.

"Well something's lost, but something's gained/ In living every day," she sang with a soft hint of a smile, before the well of strings, clarinet, guitars, and piano brought the final chorus in.

Miley Finally Gets Her Flowers

With what appeared to be four outfit changes between the red carpet and the stage and a sky-high, Dolly Parton-inspired brown bouffant, pop superstar Miley Cyrus delivered her fair share of memorable moments throughout the evening. Cyrus arrived at the 66th GRAMMY Awards without any GRAMMYs to her name, despite two previous nominations, a slew of hit albums, and 11 Top 10 singles dating back 17 years — which made her two wins even more noteworthy.

The GRAMMY drought ended thanks to smash single “Flowers,"which won Best Pop Solo Performance and Record Of The Year, solidifying Cyrus’ place both in GRAMMY history and as one of the year’s most celebrated pop stars.

The former teen star took the stage at the 66th GRAMMY Awards as well, delivering “Flowers” to a star-studded — a daunting task for anyone, even a seasoned star. But it should have come as no surprise that Cyrus would be comfortable in that spotlight, as evidenced by her joking question for the entire room (and, it seemed, viewers at home, too): "Why are you acting like you don't know this song?"

Despite her glowing near-speechlessness at finally earning a GRAMMY, the comfortable quips didn’t stop there. "I don't think I forgot anyone, but I might've forgotten underwear... bye!" she exclaimed before zipping offstage with her brand new GRAMMY hardware.

Celine & Mariah: Presenters Make History, Too

Even when just presenting awards, powerful women were at the forefront at the 66th GRAMMY Awards. The evening’s first presenter was Mariah Carey, onstage just three days after receiving the Impact Award from the Recording Academy’s Black Music Collective. The five-time GRAMMY-winner received the honor for her art’s influence and her inspirational legacy of service — and considering the ovation in the room, that impact was felt by her peers as well as the fans watching along at home.

Carey was presenting for Best Pop Solo Performance, and used her inimitable falsetto to deliver the ecstatic announcement: "And yes, this year all five nominees are women!" The sight of Carey handing Miley Cyrus her first GRAMMY (in honor of disco-tinged bop "Flowers") was, as Miley aptly put it, "too iconic."

While that opening set the stage for women dominating the show, the other bookend to the evening’s awards proved perhaps even more tear-jerking. At the end of 2023, the update came that Celine Dion’s battle with the rare neurological disorder "stiff person syndrome" had left the legendary vocalist without full control of her muscles, sometimes causing trouble walking or even using her vocal cords. As such, the sight of her walking down the golden tunnel and up to the microphone to announce the nominees for Album Of The Year felt like a special honor in and of itself.

"When I say that I’m happy to be here, I really mean it from my heart," she said. "Those who have been blessed enough to be here at the GRAMMY Awards must never take for granted the tremendous love and joy that music brings to our lives and to people all around the world."

Dion offering those lines — that positivity and beauty in the face of unprecedented difficulty — before presenting the award that would make history for Taylor Swift felt so fitting, emblematic of the powerful women who made the evening what it was.

Check Out The Full Winners & Nominees List For The 2024 GRAMMYs