Photo by Getty Images/Getty Images

Jefferson Airplane at Woodstock 1969

news

Why Can't Anyone Get Woodstock Right? 15 Of The Original Fest's Performers Weigh In

The Recording Academy spoke with 15 performers from Woodstock '69 about how they plan to ring in the 50th this weekend (or not), and why no one has successfully recreated the original experience

John Sebastian was onstage at the Woodstock Festival when a stage runner came bearing rough news: the fence had come down. Despite a meager $6 per day admission, demand had vastly exceeded supply, and throngs of concertgoers had decided to break in by force. For its 24-year-old promoter, Michael Lang, this should have been a recipe for disaster. But he did what he does best, for better or worse—he thought on his feet.

"I saw Michael look into the middle distance for a minute and then say, 'I think we have ourselves a free festival,'" Sebastian tells the Recording Academy. "I said to myself, 'This guy is a genius.' And sometimes being a genius isn't making money. It’s realizing your situation and treating it for what it is." He breaks into a wry laugh. "In that case, a dangerous situation!"

50 years after Woodstock, time hasn't been kind to Lang’s seat-of-his-pants business style. Woodstock '94 was plagued with rain and became a gigantic mud slick. Woodstock '99 deteriorated into an alcohol-fueled nightmare, along with reports of arson, looting and allegations of sexual assault. And last month, an ill-prepared Woodstock 50 went into a legal and financial tailspin and was finally killed at the eleventh hour, after months of bluster from Lang that the show would go on.

Some surviving Woodstock acts, like Santana, Canned Heat, and Country Joe McDonald, were set to reappear at Woodstock 50; others declined the offer or weren’t asked. Now that the festival is dust, a few original Woodstock cats, like Ten Years After, Melanie and Canned Heat, plan to spend August 16–18, 2019, at small-town gatherings like WE 2019. Others are plugging away on tour that weekend. Quite a few have no plans to celebrate at all.

With Woodstock 50 a bust, the Recording Academy spoke with 15 of the original festival's performers about how they plan to ring in the 50th this weekend (or not), and why no one has successfully recreated the 1969 experience.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/AqZceAQSJvc" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>What was the original Woodstock like through your eyes?

John Sebastian: I had a pretty great catbird seat to the Woodstock festival. By that, I mean that I could go backstage at any time I wanted. I had access to a tent that was mainly for acoustic instruments, but [giggles] which at night I could use.

Nancy Nevins (Sweetwater): I felt stressed out, as much as any 19-year-old can feel that way. Woodstock was a mess in every way as far as being a performer there goes.

Doug Clifford (Creedence Clearwater Revival): It was a logistical nightmare from where we were. We were exhausted from a red-eye flight, doing television all the day before.

Stu Cook (Creedence Clearwater Revival): It was the summer of festivals. There were a lot of big festivals. Bigger than Woodstock, actually, in terms of attendance.

Fred Herrera (Sweetwater): We had been playing numerous outdoor festivals at the time, each one larger than the last. Leading up to this one, it seemed like just another. When we arrived, we realized the magnitude of the event, but I figured the next one could be larger.

Nevins: Plus, Sweetwater had a serious mission to accomplish beyond Woodstock, which is why we played first. We had to get [keyboardist] Alex [Del Zoppo] back to Riverside, California by 6 a.m. on Saturday… or else. He was in the Air Force Reserve. Their annual two-week training camp started in Riverside the next [morning]. This was non-negotiable. I was preoccupied with that need, which made everything else, like the crappy sound and general stage conditions, enormously burdensome.

Clifford: We went in on a two-man helicopter with three people. I was half in and half out of the helicopter. I had my right foot on the skid, hanging out the door, which was open, of course. I was holding the seatbelt of the seat next to me to stabilize myself.

Gregg Rolie (Santana): [The view] really impressed me. Like ants on a hill. Past 10,000 people, it's just hair and teeth. It's just brown. It didn't register.

Roger North (Quill): Having studied structural engineering in college, I remember being very concerned that the overhead lights and rigging were in danger of being toppled onto the stage by the wind of the oncoming rainstorm.

Miller Anderson (Keef Hartley Band): Our manager refused to let us be filmed without a contract. That was a big mistake for our band.

Jorma Kaukonen (Jefferson Airplane): By the time that it came for us to go on, it became apparent that they were running really behind schedule. As everybody knows, we waited around all night and didn’t go on until Sunday morning.

Sebastian: I was standing on the stage when the runner came from the back porch of the festival, saying "The fence has gone down." I saw Michael look into the middle distance for a minute and then say, "I think we have ourselves a free festival." I said to myself, "This guy is a genius." And sometimes being a genius isn't making money. It’s realizing your situation and treating it for what it is. In that case, a dangerous situation!

David Clayton-Thomas (Blood, Sweat & Tears): We were basically only there for a couple of hours. We did our encore, got a tremendous reception and immediately after the show, back on the helicopter and gone.

Billy Cox (Jimi Hendrix/Gypsy Sun & Rainbows): Jimi looked out from behind the curtain at the crowd and said: "That crowd out there will be sending us a lot of energy up onstage, so let’s take that energy, utilize it and send it right back to them." Mitch had a bottle of Blue Nun wine with him. As if we were making a toast, Jimi, Mitch and I each took a large swig from it, smiled at each other, and went out and played for almost two hours.

Robin Williamson (The Incredible String Band): I’d rather not keep getting dragged back into the '60s. I’d like to be one of the first people over the mountain.

David Crosby (Crosby, Stills & Nash): What happened was that half a million people treated each other decently. I don’t think there's ever been a gathering of half a million people anywhere where there were no rapes, no robberies, no murders. None. People behaved differently with each other. It was so stunning for those of us that were there that we can’t get it out of our heads. There was a moment where everything worked the way we dreamed it could.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/MwIymq0iTsw" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

What do you think about the troubles Woodstock has faced over the years? Why has it been so difficult to maintain the brand over time?

Anderson: Woodstock was very disorganized. It was nobody's fault. The organizers did not expect so many people and it just got out of hand.

Crosby: Since then, it’s been people trying to use that word, "Woodstock," as a way to make a ton of money. That's the truth of all of the rest of it that’s gone on since then.

Cook: There's a lot of people involved in that pie. If you recall, the first one was almost a disaster as well. The main problem is that the people behind the festival are not concert promoters. They have another agenda.

Skip Taylor (producer/manager of Canned Heat): Unfortunately, Michael Lang has gotten a lot of credit, but he hasn’t gotten a lot of criticism, and I’m one to give it.

Herrera: I would surmise that the original had a great deal of luck associated with its outcome, busted finances aside. Maybe the promoters of the current and subsequent ones took for granted more than they should have.

Cook: The first one happened miraculously. That was a cosmic, universe-exploding experience that could never be duplicated. The brand has suffered because it’s impossible to top itself. It can’t even match itself. Everything comes up short.

Clifford: It’s not something you can manufacture or recreate. It was real. It was the spirit of mankind, the way it was supposed to be in the first place.

Crosby: The people who did it were in it to make a ton of money. They did not care about the audience’s experience at all. They didn’t know what that experience is. They don’t really understand what magic music can [create]. If you get the right kinds of music next to each other in the right place with the right people, you can get magic. They thought you could simply buy it by the pound. You can’t.

"The first [Woodstock] happened miraculously. That was a cosmic, universe-exploding experience that could never be duplicated. The brand has suffered because it’s impossible to top itself. It can’t even match itself. Everything comes up short."

Nevins: The "bliss" that is Woodstock can't be duplicated because it's not for sale. Such acceptance, love, and good-naturedness can't be re-packaged. Try marketing authenticity and unity. It can't happen. By their nature, true spirituality and acceptance can't be marketed.

Crosby: They made a terrible mistake and all of these gigs have been failures, in my eyes anyway. Woodstock ‘94 made money, but it was a horrible, horrible experience for everybody who was there.

Sebastian: Also, the intoxicants were different in 1969. Pot being the major recreational drug, and then you compare that to Woodstock ‘99, where the problem was alcohol.

Rolie: Society changes. The social structure back then was one thing, and now, there’s a lot of angry people out there, obviously. They may have disagreed strongly [back then], but there wasn’t such violence as what you see now. Now, they try to repeat it and they charge $30 for a bottle of water!

Kaukonen: Whatever magic was in the air that gave whatever you want to call it, the counterculture, a sense of visible and concrete identity in the world at that time, that’s not going to happen today, because... that’s not going to happen. It’s not that time anymore! You just can’t expect things to magically happen anymore.

Nevins: That is why the 50th anniversary concert failed. It was designed around maximizing profit and ego strokes.

Crosby: They’re very, very greedy people doing really dumb stuff. I think that’s probably what went wrong this time.

Taylor: I blame [Lang] singlehandedly for ruining this celebration of the 50th anniversary of Woodstock, which was and still is the greatest festival that ever happened in the world.

Cox: You know, it would have been interesting had a call been made for as many of the gatherers and performers at Woodstock to convene on the 50th anniversary and help tilt the scales and maybe fate would have been pleased. We’ll never know.

Williamson: I don’t really know anything about what’s going on with Woodstock 50. I haven't been following that at all. I’ve been trying to do things in the present time and look toward the future, really.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/OxO5LKUaodk" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

What do you plan to do to celebrate Woodstock’s 50th anniversary, if anything?

Crosby: Nothing.

Clifford: Probably take my grandkids out to dinner.

Jocko Marcellino (Sha Na Na): Cruising the North Sea on vacation.

Cook: Scuba diving in Roatán.

Rolie: I’ll be there on August 16th with Ringo [Starr & His All-Starr Band] at Bethel Woods [Center for the Arts]. We’re going to be doing the Santana stuff. That’s what I play with Ringo.

Kaukonen: Let’s see. I’m going to be on the road. If I was home, I’d probably take my wife and daughter out to dinner.

Williamson: In the U.K., there’s not much to celebrate here. I wasn’t planning on doing anything about it here.

North: I will be thinking about the festival, but I have plans to maybe spend some time in the woods that weekend.

Kaukonen: You know what, honestly? I’ll probably write something on my blog about it, just from a memory point of view. I don’t see how you can celebrate something in a concrete way that was that ephemeral.

Anderson: I have my own band, the Miller Anderson Band. We are playing festivals celebrating 50 years of Woodstock all over Europe.

Nevins: I'm celebrating the 50th with gratitude. For living through those years, for knowing most people have goodness in them, and knowing that our current states of material ignorance are not the Alpha and Omega of humankind. There is a better us and the artists will bring it out first. The entrepreneurs and business addicts never will.

Clayton-Thomas: They’re not "celebrating" [with these 50th anniversary shows]. It’s just a bunch of promoters trying to cash in on the name again. People aren’t buying it. People understand that it was a unique moment in history and it will never happen again.

Herrera: Sweetwater has already been performing at a number of Woodstock-themed events, including outdoor and indoor concerts, TV shows, radio, blogs and Q&A appearances, all associated with the 50-year anniversary.

Sebastian: I’m playing all around that date like crazy, and I would have played the date if [Michael Lang] hadn’t moved to Maryland, because I already had a gig in Maryland, and they’ve got those kinda rules where if I’m gonna hire you to play my gig, you can’t play somewhere [nearby] next week. I was right there with him up until when I couldn’t be with him.

Taylor: There are other things happening around the country other than just the one Woodstock 50. Fortunately, we’re partaking in a lot of them.

Clayton-Thomas: I don’t. I’ve turned down half a dozen offers to play these reunions. It’s mostly cover bands, other bands or a band that was at Woodstock’s bus driver who now has a band… you know? It’s gone. It’s history. It’s over.

Crosby: What I told you definitely happened. That was the significance of it. If you give a sh*t about what I’m telling you, pay attention to that. That’s where the real value was. And that’s what’s absent here.

David Crosby On 'Remember My Name': "It's An Opportunity To Tell The Truth"

Photo: Dave Hogan/Getty Images

list

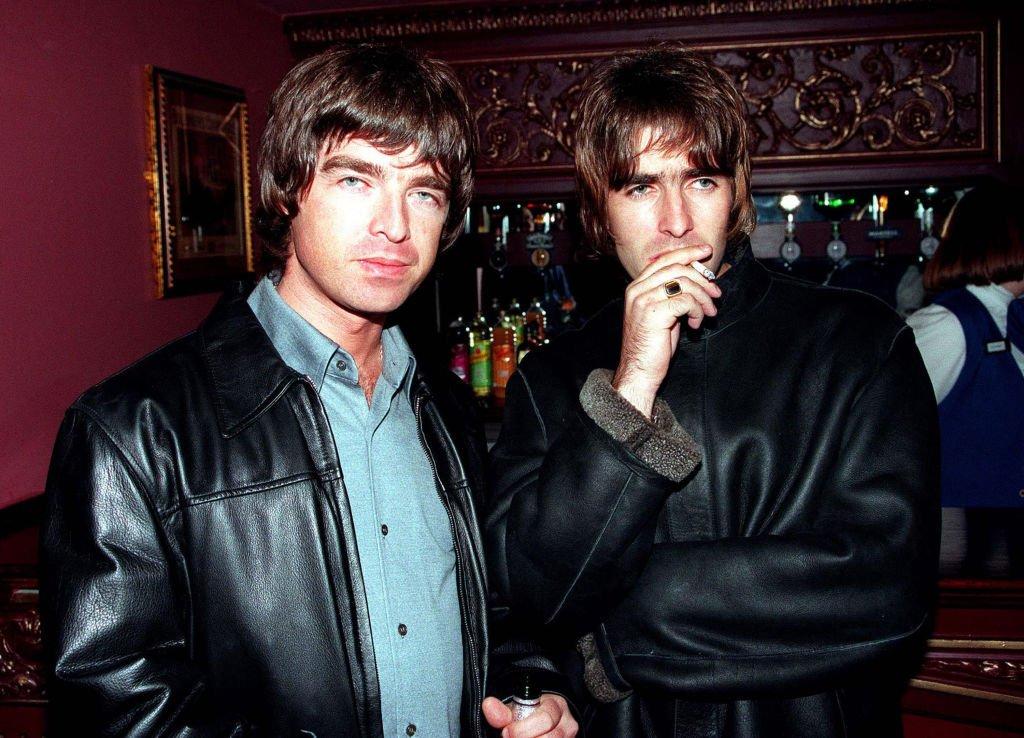

7 Musical Sibling Rivalries: CCR, Oasis, The Kinks & More

Sometimes arguments between siblings are brief and forgiving. Other times, the damage is irreparable. Read on for seven historic sibling rivalries, break-ups and reunions in rock and pop history.

It stands to reason that, in music, the family that plays together stays together, although that’s not always the case.

For every Kings of Leon, Haim, Jonas Brothers, Jackson 5, Osmonds, Isley Brothers, Bee Gees or Hanson that stand the test of time, there are other family-based groups where the grueling and interdependent nature of rock stardom has led to dissension in the ranks.

Sometimes those arguments between siblings are brief and forgiving. On other occasions, wedges are forged and sides are taken, resulting in either a permanent breakup of an act; a launch into new creative horizons; or hopefully a reconciliation.

Here are seven well-known acts whose internal bickering between has led to either unexpected ends or surprising detours

The Everly Brothers: Don & Phil Everly

The Everlys' close-knit country pop and rock 'n' roll harmonies — which netted immortal chart-toppers "Bye Bye Love," "Wake Up, Little Susie" and "All I Have To Do Is Dream" — inspired everyone from the Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel to Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris. As such, it's difficult to fathom that the Don and Phil Everly were so at odds for the better part of a decade that they'd spend entire evenings together on stage without exchanging a word.

A 2014 Los Angeles Times article reported that "vastly different views on politics and life," drove a wedge between Don and Phil. The brothers broke up at least twice; their first estrangement followed a 1973 show at the California theme park Knott's Berry Farm, when Phil smashed his guitar and walked offstage.

That split resulted in separate careers up until a 1983 reunion at London's Royal Albert Hall and the recording of several albums, including EB'84 with producer Dave Edmunds.

Phil Everly died of pneumonia in 2014 at the age of 74, while Don succumbed to undisclosed causes at the age of 84 in 2021.

It is unknown if the GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award recipients ever reconciled.

The Louvin Brothers: Ira & Charlie Louvin

Grand Ole Opry legends and brothers Charlie and Ira Louvin are known for such songs as "I Don't Believe You've Met My Baby" and "Hope That You're Hoping."

Born in Henagar, Alabama, the Louvin's country, bluegrass and gospel sound developed from their strict Baptist upbringing. Yet the brothers preached one philosophy in song, Ira, who complemented Charlie's guitar on mandolin, lived another: His inability to resist vices — drinking and womanizing — prompted Charlie to go solo in 1963.

Ira continued to lead a colorful life: his third wife shot him four times in the chest and twice in the hand after he allegedly tried to kill her with a telephone cord- but Louvin survived.

However, it was a 1965 car crash that eventually claimed Ira and his fourth wife, Anne: they were killed by a drunk driver.

The tragedy cut short any chance of a duo reunion, although Charlie enjoyed several Top 40 country hits through 1971.

The Louvin Brothers were enshrined in the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001.

The Kinks: Ray & Dave Davies

English rock rebels the Kinks have sold more than 50 million albums since forming in the '60s, although most of their hits — "Lola," " You Really Got Me," "Apeman," "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" and "Come Dancing" among others — stemmed from the pen of Ray Davies.

Contrary to popular belief, brother Dave says he is good with that equation — but admits that the relationship between them is naturally tumultuous.

Dave Davies explained the dynamics of his relationship with Ray to The Daily Mail in 2017, describing it as "a married couple who have just reached the end of the road."

"You know when one partner gives and gives and the other takes, and finally you realise (sic) you can’t do it any more?’

"You can’t divorce your brother, though. ‘No, you can’t. So we are stuck with each other, but I think I’ve accepted that this is just the way our relationship is.

In a separate interview with The Daily Express in 2011, Ray agreed. "When we were together it was aggressive, violent, powerful but we triggered off each other."

Still, the dust-ups between them were legendary, leading to a two-decade rift.

As recently as 2018, there's been talk that Ray and Dave Davies had buried the hatchet and were intent on reuniting the Kinks... but here we are in 2023 and that possibility seems no closer to reality.

Creedence Clearwater Revival: John & Tom Fogerty

After American rockers Creedence Clearwater Revival (CCR) formed in El Cerrito, California in 1959 (they began as the Blue Velvets and rechristened themselves several times before settling on CCR in 1968), it was clear that lead singer, guitarist and songwriter John Fogerty was calling the shots — including acting as the band's manager.

CCR included Fogerty's brother Tom, who played rhythm guitar; bass player Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford. Following a particularly lucrative period between 1969 and 1970, John decided that Tom would no longer sing lead on or co-write any song while he was in the band, despite previously handling lead vocals and collaborating on some pre-CCR material.

"He cut Tom Fogerty out from singing," Clifford told AZ Central in 2015. 'Without Tom...there wouldn't have been a Creedence Clearwater Revival. When Tom graciously gave up the vocals to his younger brother, he had no idea that he would never be singing another song again. So Stu and I and Tom were always at odds with John about that."

Tom Fogerty left after 1970's Pendulum, and apart from a 1980 reunion during his wedding reception, CCR never performed again. He died in 1990 after contracting AIDS from HIV-infected blood during a transfusion during back surgery, and was posthumously inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

Heart: Ann & Nancy Wilson

One of the top female-led rock bands in modern music history thanks to hits like "Magic Man" and "What About Love," Heart has been the role model for thousands of musicians.

But the first public signs of friction between sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson occurred in August 2016, when Ann's husband Dean Wetter was arrested for assaulting Nancy's 16-year-old twin sons after he boys reportedly left open the door to his RV.

Rolling Stone reported that the siblings hadn't spoken to each other since the 2016 tour ended, but relations have eventually warmed up. The sisters reunited for Heart's 53-date Love Alive tour in 2019 - and more recently, Nancy joined Ann Wilson and her band Tripsitter on stage October 10 in Santa Rosa California to perform "Barracuda." They received the Recording Academy's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2023.

Ann Wilson has continued to release solo albums and front her band Tripsitter, while guitarist Nancy has formed Nancy Wilson's Heart.

In a 2022 Guitar World interview, Ann said she and Nancy are "okay," but have different ideas for the future of Heart. "We haven't figured out a compromise yet," she admitted.

The Black Crowes: Chris & Rich Robinson

Sometimes, money and control carry more weight than people insinuate.

Guitarist Rich Robinson left the Black Crowes in January 2015 due to an alleged ownership agreement with brother and vocalist Chris. Both men divided and conquered with solo careers but remained largely incommunicado for almost five years.

But in an interview with the San Diego Union-Tribune, both Rich and Chris credited their children with healing the rift between them.

"My daughter, Cheyenne (now 11), was like: ‘What’s the deal with you and Uncle Rich, and why don’t I know my cousins?’"Chris told the paper. "Those are the kind of questions that will make you think and reflect."

"Definitely. Kids are honest and curious, and they don’t have issues like Chris and I did," Rich said in a joint interview with his brother. "So, as Chris said, that opened a door (to reconciliation)."

Together again since 2021, the Black Crowes will be shaking their moneymakers opening the final Aerosmith tour, once Steven Tyler's larynx heals.

Oasis: Liam & Noel Gallagher

While backstage in 2009 in Paris, the tumultuous in-fighting between Oasis' Liam and Noel Gallagher reached new heights; a violent fistfight that drove a nail into the coffin of the band.

Noel's statement: "It's with some sadness and great relief to tell you that I quit Oasis tonight. 'People will write and say what they like, but I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer."

This was the last in a number of physical altercations that had taken place over the years during tours. Since the split, Noel has been recording and touring with his band the High Flying Birds while Liam first took to the road and studio with Beady Eye, which split in 2014; he's now performing solo.

However, Liam has reportedly expressed interest in reuniting with Noel and strike up Oasis, though whether there have been any private conversations towards this end remains to be seen.

11 Iconic Concert Films To Watch After 'Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour'

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

list

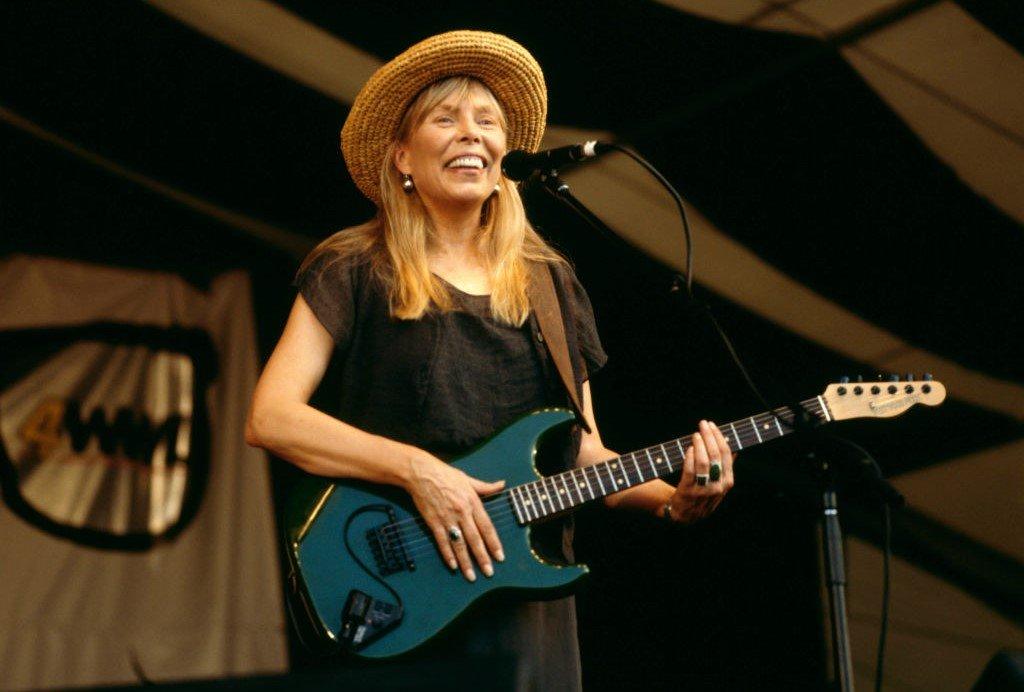

10 Lesser-Known Joni Mitchell Songs You Need To Hear

In celebration of Joni Mitchell's 80th birthday, here are 10 essential deep cuts from the nine-time GRAMMY winner and MusiCares Person Of The Year.

Having rebounded from a 2015 aneurysm, the nine-time GRAMMY winner and 17-time nominee has made a thrilling and inspiring return to the stage. Many of us have seen the images of Mitchell, enthroned in a mockup of her living room, exuding a regal air, clutching a wolf’s-head cane.

Again, this adulation is apt. But adulation can have a flattening effect, especially for those new to this colossal artist. At the MusiCares Person Of The Year event honoring Mitchell ahead of the 2022 GRAMMYs, concert curators Jon Batiste — and Mitchell ambassador Brandi Carlile — illustrated the breadth of her Miles Davis-esque trajectory, of innovation after innovation.

At the three-hour, star-studded bash, the audience got "The Circle Game" and "Big Yellow Taxi" and the other crowd pleasers. But there were also cuts from Hejira and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Night Ride Home, and other dark horses. There were selections that even eluded this Mitchell fan’s knowledge, like "Urge for Going." Batiste and Carlile did their homework.

But what of the general listening public — do they grasp Mitchell’s multitudes like they might her male peers, like Bob Dylan? Is her album-by-album evolution to be poured over with care and nuance, or is she Blue to you?

Of course, everyone’s entitled to commune with the greats at their own pace. However, if you’re out to plumb Mitchell’s depths beyond a superficial level, her 80th birthday — which falls on Nov. 8 — is the perfect time to get to know this still-underrated singer/songwriter legend better. Here are 10 deeper Mitchell cuts to start that journey, into this woman of heart and mind.

"The Gallery" (Clouds, 1969)

Mitchell blew everyone’s minds when David Crosby discovered her in a small club in South Florida. Her 1968 debut, Song to a Seagull, contains key songs from that initial flashpoint, like "Michael from Mountains" and "The Dawntreader."

Mitchell’s artistic vision truly coalesced on her second album, Clouds. Although the production is a little wan and bare-boned, Clouds contains a handful of all-time classics, including "Chelsea Morning," "The Fiddle and the Drum" and the epochal "Both Sides, Now."

That said, "The Gallery," which kicks off side two, belongs at the top of the heap. There remain rumblings that it’s about Leonard Cohen. But whatever the case, Mitchell’s excoriating burst of a pretentious cad’s bubble ("And now you're flying back this way/ Like some lost homing pigeon/ They've monitored your brain, you say/ And changed you with religion") remains incisive, with a gorgeous melody to boot.

(And, it must be said: "That Song About the Midway," also found on Clouds, is a kiss-off to Croz, whom she enjoyed a fleeting fling with and a must-hear.)

"Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire" (For the Roses, 1972)

If you think you’ve got a grasp of Mitchell’s early talents, a new archival release proves they were more prodigious than you could imagine.

Joni Mitchell Archives, Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975) kicks off with a solo version of "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire." And as great as the studio version is, from 1972’s For the Roses, this version, from a session with Crosby and Graham Nash, arguably eats its lunch.

While Neil Young’s "The Needle and the Damage Done" has proved to be the epochal junkie-warning song of the 1970s, Mitchell’s song about the same subject easily goes toe to toe with it.

Images like "Pawn shops crisscrossed and padlocked/ Corridors spit on prayers and pleas" and "Red water in the bathroom sink/ Fever and the scum brown bowl" are quietly harrowing. Via Mitchell’s acoustic guitar, they’re underpinned by downcast, harmonically teeming blues.

"Sweet Bird" (The Hissing of Summer Lawns, 1975)

The Hissing of Summer Lawns is an unquestionable masterstroke of Mitchell’s fusion era.

Highlights are genuinely everywhere within Lawns — from the swinging and swaying "In France They Kiss on Main Street," to the Dr. Dre-predicting "The Jungle Line," to the title track, a hallucinatory lament for a trophy wife.

But amid these manifold high points, don’t miss "Sweet Bird," the penultimate track on The Hissing of Summer Lawns, tucked between "Harry’s House/Centerpiece" and "Shadows and Light."

"Give me some time/ I feel like I'm losing mine/ Out here on this horizon line," Mitchell sings through her dusky soprano, as the ECM-like atmosphere seems to whirl heavenward. "With the earth spinning/ And the sky forever rushing/ No one knows/ They can never get that close/ Guesses at most."

"A Strange Boy" (Hejira, 1976)

Much like The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira — retroactively, and rightly, canonized as one of Mitchell’s very best albums — is nearly flawless from front to back.

The highs are so high — "Amelia," "Hejira," "Refuge of the Roads" — that almost-as-good tracks might slip through the cracks. "A Strange Boy," about an airline steward with Peter Pan syndrome she briefly linked with.

"He was psychologically astute and severely adolescent at the same time," Mitchell said later. "There was something seductive and charming about his childlike qualities, but I never harbored any illusions about him being my man. He was just a big kid in the end."

As "A Strange Boil" smolders and begins to catch flame, Mitchell delivers the clincher line: "I gave him clothes and jewelry/ I gave him my warm body/ I gave him power over me."

"Otis and Marlena" (Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, 1977)

One of Mitchell’s most challenging and thorny albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is one of Mitchell’s least accessible offerings from her most expressionist era. (Mitchell in blackface on the cover, as a character named Art Nouveau, doesn’t exactly grease the wheels — to put it mildly.)

But across the sprawling and head-scratching tracklisting — which includes a seven-minute percussion interlude, in "The Tenth World" — are certain tunes that belong in the Mitchell time capsule.

One is "Otis and Marlena," one of the funniest and most evocative moments on an album full of strange wonders. Mitchell paints a picture of a cheap vacation scene, rife with "rented girls" and "the grand parades of cellulite" against a "neon-mercury vapor-stained Miami sky."

And the kicker of a chorus juxtaposes this dowdy Floridan outing with the realities up north, e.g. the 1977 Hanafi Siege: "They’ve come for fun and sun," MItchell sings, "while Muslims stick up Washington."

"A Chair in the Sky" (Mingus, 1979)

While Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is rather glowering and unwelcoming, Mingus is a cracked, cubist realm that’s fully inhabitable.

Initially conceived as a collaboration between Mitchell and four-time GRAMMY nominee Charles Mingus, it ended up being a eulogy: Mingus died before the album could be completed.

Despite its lopsided nature — it contains five spoken-word "raps," as well as a true oddity in the eerie, braying "The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" — Mingus remains rewarding almost 45 years later. And the Mingus-composed "A Chair in the Sky," with lyrics by Mitchell, is arguably its apogee.

Like the rest of Hejira, "A Chair in the Sky" features Jaco Pastorius and Wayne Shorter from Weather Report, as well as the one and only Herbie Hancock; this ethereal, ascendant track demonstrates the magic of when this phenomenal ensemble truly gels.

"Moon at the Window" (Wild Things Run Fast, 1982)

In Mitchell’s trajectory, Wild Things Run Fast represents the conclusion of her fusion phase, in favor of a more rock-driven sound — and, with it, the sunset of her second epoch.

Following Wild Things Run Fast would be 1985’s critically panned Dog Eat Dog and 1988’s even more assailed Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm. But for every arguable misstep, like the guitar-squealing "You Dream Flat Tires," there’s a baby that shouldn’t be thrown out with the bathwater.

One is "Chinese Cafe/Unchained Melody," another is "Ladies’ Man," and perhaps best of all is the luminous "Moon at the Window," where bassist/husband Larry Klein and Shorter wrap Mitchell’s sumptuous lyric, and melody, in spun gold.

"Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" (Night Ride Home, 1991)

At the dawn of the grunge era, Mitchell found her way back to her atmospheric best, with the gorgeously written, performed and produced Night Ride Home.

While its follow-up, Turbulent Indigo, won the GRAMMY for Best Pop Album (and is certainly worth savoring), Night Ride Home might have more to offer those who were enraptured by the majestic Hejira, and thirsted for a continuation of its aural universe.

The equally excellent "Come in From the Cold" is the one that has ended up on Mitchell setlists in the 2020s, but "Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" is even more transportive.

Despite the early 1900s sonics, "Passion Play" feels ageless and eternal, tapped into some Jungian collective unconscious as a wizened Mitchell posits, "Who’re you going to get to do your dirty work/ When all the slaves are free?"

"No Apologies" (Taming the Tiger, 1998)

If Night Ride Home sounds less played than conjured Taming the Tiger is like the steam that twists and disperses from its broiling, potent stew.

As much ambience pervaded Night Ride Home, Hejira and the like, Taming the Tiger is the only album in Mitchell’s estimable catalog to feel ambient.

Much of this is owed to Mitchell’s employment of the Roland VG-8 virtual guitar system, which allowed her to change her byzantine guitar tunings at the push of a button; the ensuing sound is a suggestion of a guitar, which enhances Taming the Tiger’s diaphanous and ephemeral feel.

"No Apologies" is something of a centerpiece, where Mitchell sings of war and a dilapidated homeland, sailing forth on a cloud of Greg Liestz’s sonorous lap steel.

"Bad Dreams" (Shine, 2007)

Mitchell has always cast a jaundiced eye at the music industry machine, so it’s no wonder she hasn’t released a new album in 16 years. (Although, as she revealed to Rolling Stone, she’s eyeing a small-ensemble album of standards with her old mates in the jazz scene.)

But if Shine ends up being her swan song, it’d be a fine farewell. "Bad Dreams" — written around a quote from Mitchell’s 3-year-old grandson: "Bad dreams are good / In the great plan" — is impossibly moving.

Therein, Mitchell considers an Edenic tableau as opposed to our modern world, where "these lesions once were lakes." Movingly, the song’s final lines accept reality for what it is ("Who will come to save the day? / Mighty Mouse? Superman?") rather than what she wishes it could be.

With that, Mitchell’s studio discography — as we know it today — reaches its conclusion. But although the artist is only fully getting her flowers today, we’ve only scratched the surface of the gifts she’s bestowed upon us.

Living Legends: Judy Collins On Cats, Joni Mitchell & Spellbound, Her First Album Of All-Original Material

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Jacob Shije

interview

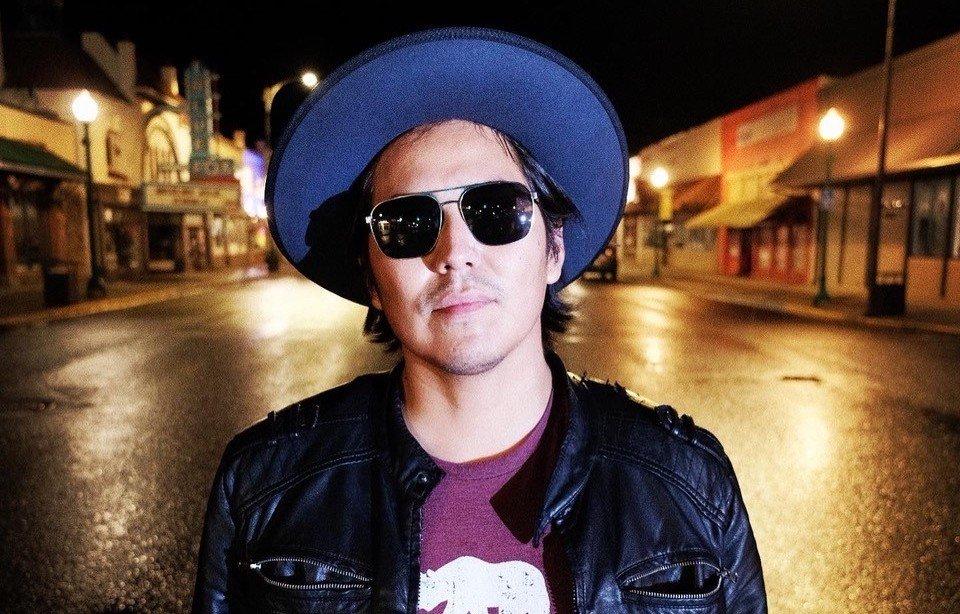

Meet Levi Platero, A Formidable Guitarist Bringing Blues-Rock To The Navajo Nation

"I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar," the guitar scorcher tells GRAMMY.com. But limelight or not, Levi Platero's illuminating a path forward for blues-rock in Indigenous communities.

Back in 2022, Levi Platero spoke to GRAMMY.com about his then-new album, Dying Breed. Two days later, a city bus slammed into his touring van.

The Arizonan blues-rock guitarist, who hails from the Eastern Agency of the Navajo Nation, was on a West Coast tour. After lunch in downtown Portland, kaboom: their van was totaled. When hearing about this close call, something poignant Platero had said came to mind.

"I just want to be able to keep going, man. Especially with blues music, you can kind of play forever," he expressed near the end of the interview. "Not to put down any other musical genres, but I can't see myself being a rap artist at, like, 60 or 70 years old. I can see myself being a blues-rock guy until the day I die."

Looking decades into the future, it's hard not to imagine Platero and his music being buoyed by the community he helped create.

An absolute burner on his instrument — behold Dying Breed highlights like "Fire Water Whiskey" and "Red Wild Woman" as examples — he stands with few others as a blues-rock great in the Navajo Nation. Or just one, in his estimation: Mato Nanji of the band Indigenous, who he affectionately calls "Big Brother."

Perhaps Platero — who's eyeing a new van, and getting ready to head back into the studio in late spring — will also inspire others in his wake. And the more he sings and plays, the more likely that outcome seems — that his "dying breed" will flourish forever.

Read on for an in-depth interview with Platero about his latest album, how Indigenousness inspires his artistry, and why he "doesn't want to be a superstar — I just love to play."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about your background, and the musical community that brought you up.

I grew up in church. My dad was an evangelist. He went out, did things for the church and that kind of community. I would sometimes tag along, but I was getting involved with some of the worship leading and stuff like that. But my dad would write his own tunes, and he would make his own music later on. And I would go out and help him just play drums. I was just in the background area.

Later on, I started playing guitar, and listening to a lot of old gospel tunes and gospel hymns. That's where I got introduced to the blues. And after I learned about the blues, from then on, that's all I ever really listened to.

Now, a lot of things have changed. I'm out in the world doing my own thing and writing my own music about some things that I feel — not necessarily anything that has to do with the church community. But, that's where I got started.

What's your conception of the blues? To me, it's kind of like the word punk. It can be a certain way of playing power chords, or an entire state of being — an opposition to the status quo. Likewise, the blues can mean 12 bars, or the totality of human angst.

I think it's probably the rawest form of musical emotion that I can feel — that I've ever really felt for myself. But that's only my own opinion. That's my perception of it. I always hear a lot of people say that it's a little redundant, and it's kind of boring and whatnot. But for me, it's something that's just really raw, emotional, really straightforward.

And as far as the lifestyle, I mean, I would have to say that being a part of a blues community, I'm really [grounded among] people who are really respectful.

And the people who are respected the most are the people who generally [may] not have the most talent, but collectively, they're a great person — they have a great personality. They really enjoy one another's music, and they're really involved in the blues community where they help each other out, or they get each other's gigs, they sit in.

It's just this really friendly dynamic in that area. Rather enjoyable. I love it.

Living or dead, whether you know them or not, who are the guitarists that formed you?

I have to say my biggest influence was Mato Nanji from Indigenous. They were a Native American blues-rock group back in the day, probably in the early 2000s. They made a really good name for themselves in the blues circuit, and I [had] the opportunity to actually travel and open up for him and also join his band.

I really learned a lot from kind of hanging out with him and just being a part of his group. He's one of my biggest guitar influences and as a person — as a role model.

Otherwise — people who I have not met — I have to say, of course, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan. David Gilmour was a good influence. Doyle Bramhall II — little Doyle, big Doyle.

And then as far as in my community, back in Albuquerque, Darin Goldston — he plays for the Memphis P-Tails. He hosts the blues jam every Wednesday night. Whoever is upcoming and just wants to play some blues, they come out and jam. It's pretty awesome.

And, of course, Ryan McGarvey. If you don't know who that is, he's in the blues-rock circuit. He's a great guy — a pretty influential person.

With all those inspirations on the table, how did you start to develop your own voice on the guitar?

Just being well-seasoned, I guess. Just constantly playing over time. For some people, it doesn't happen right away, to find their own sound. With other people, they have to go through seasons and learn new things, until one day, they really become identifiable just by the first couple of notes they play.

I don't think it was a hard thing for me. I was just playing until it started becoming identifiable to some people's ears.

I'm sure specifically Indigenous influences must make it into your sound in some way.

Yeah, of course. I mean, those drum patterns, those drum beats — they're really similar to all that chain gang stuff they used to do back in the day. Those call-and-repeats and stuff like that.

Sometimes I try to incorporate that into some of the music I have. Indigenous influences are there, as far as jewelry and hats. Even as far as a little bit of graphic design. That stuff definitely makes its way into the fashion part, and the promotion.

Tell me what you were trying to artistically impart with Dying Breed.

I just wanted to put out an album, because I need to. I love writing my own music, and of course, the ultimate goal is to make music that inspires and reaches people — and also inspires Indigenous artists and people at reservations to go after whatever they want to go after.

Because it's like: yeah, there's education on the rez, but as far as outlets — fashion, music, art, film — some of those things don't make it as far as the reservation.

So, just being an Indigenous artist in itself — to be able to write and put out music like that, for others to hear — I guess that's kind of the ultimate accomplishment in what I'm trying to do. Just to keep inspiring people — inspiring my own people, natives all across the U.S.

**Can you talk about your collaborators on Dying Breed?**

That's actually kind of funny, because I'm doing most of the work on the album.

I did all the guitars. I did all the bass guitars. I did the lead vocals. My cousin [Royce Platero] did the drums. I only had my rhythm player [Jacob Shije] play on, like, two tracks, and he was only doing small-fill guitars and that's it. I had a good friend of mine named Tony Orant come in and play keys on two of the songs as well.

As far as all the songs go, I wrote all of them. I composed everything. I came up with the arrangements and the core progressions. I mean, it's all mine.

One of my favorite people and producers right now, a sound engineer who helped me with the album: his name is Ken Riley and he's based out of Albuquerque. He has a really beautiful and awesome old adobe recording studio, right by the Rio Grande. It's called Rio Grande Studios. He's kind of a legend. He's worked with so many artists and still works with big-name, major artists.

I think he recently just worked on Micki Free's album. He worked on a couple of songs with Santana and Gary Clark Jr. Christone ["Kingfish"] Ingram. He works with some heavy hitters, and I approached him. I was introduced to him by a friend of mine named Felix Peralta. He told me to meet this guy and said, "You need to do your next record here."

So, we finally got to meet, me and Ken, and it just kind of went from there and everything came out really good. I really enjoy this record. It's probably my favorite one that I've done so far.

*Levi Platero. Photo: Jacob Shije*

Are there any other Indigenous musicians in the blues and/or Americana world that you want to shout out in this interview?

Foremost, as far as blues guitarists: I have to give a shout-out to my — I call him Big Brother. Mato Nanji, and that means "standing bear." He's a big role model, and probably the only other Indigenous blues-rock guitarist out there besides me who is trying to do it.

Anything else you want to mention before we get out of here?

No, I just want to keep playing. I just want to keep doing this — meet more people, keep expanding. I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar. I just love to play. I just want people to enjoy my music and come vibe at the shows. That's it.