Photos (L-R): Ricrdo Rubio/Europa Press via Getty Images, Martyn Goddard/Corbis, Pete Cronin/Redferns, Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Jethro Tull

feature

Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From 'This Was' To 'The Zealot Gene'

Despite being a staple of 1970s rock, Jethro Tull remain bizarrely underrated — they're one of the most cerebral, idiosyncratic and affecting bands of all time. With their comeback LP 'The Zealot Gene' on the way, here's a guide to their 22 albums.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond.

Ian Anderson recently released Silent Singing, a full compendium of his lyrics with his band, Jethro Tull, and from his solo career. He doesn't expect most people to seek it out, much less absorb it — and he's perfectly OK with that.

"They are perfectly entitled to — and perhaps best advised to — just listen to the music and sing along, or tap their foot and enjoy it on a relatively basic level," the bandleader tells GRAMMY.com of the book, which spans his life's work since 1968. "They're not all necessarily interested in what lies behind it."

In other words, Anderson's not here to lecture listeners about the wonders of cutting-edge technology, the corruption of organized religion, or the joys of animal life. He makes rock songs, not TED Talks.

But what if you do want to dig deeper than the top-line information about Tull? Anderson put out Silent Singing for the more invested portion of his fan base — those who know his art beyond the famous Anchorman scene.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//f7SGq7jMdSU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Flip to even the most obscure entry, like the one for "Wond'ring Again," a sequel to Aqualung's love song "Wond'ring Aloud," buried in the 1972 compilation Living in the Past, and the cerebral, furious and evocative lyrics might blow your hair back.

"The excrement bubbles / The century's slime decays," it goes. "Incestuous ancestry's charabanc ride / Spawning new millions, throws the world on its side." Unfurling its predecessor's purview until it encompasses everything, Anderson condemns an overpopulated, coarsening society plundering its only home. It’ll give you goosebumps if you're in the right mood. It's quintessential Tull.

Wielding a freight-train intellect, a bookworm's vocabulary, and underdiscussed melodic gifts (despite his limited vocal range), Anderson has penned a few dozen tunes that belong in the Tower of Song — from the white-knuckled "Locomotive Breath" to the enchanting "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All" to the exquisite "Moths." And the more you plumb beneath the surface — the riffs, the flute, the, er, codpiece — the more rewarded you'll be.

On Jan. 28, the English progressive rock titans are back with The Zealot Gene. It may be their first album in almost two decades, but their idiosyncratic vision remains undeterred. Drawn from Biblical accounts and morality lessons, songs like "Shoshana Sleeping," "The Betrayal of Joshua Kynde" and "In Brief Visitation" peer under the hood of the human condition like only Anderson can.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://open.spotify.com/embed/playlist/2dwK0Gx6D9s3YotJLMeBuC' width='100%' height='380' frameBorder='0' allowtransparency='true' allow='encrypted-media'></iframe></div>

Despite Tull's considerable creative powers — and being a staple of hard-rock radio — they remain bizarrely underrated. Like fellow '70s hitmakers Randy Newman and Steely Dan, the press has pigeonholed them with superficial characterizations. The mordant Newman is most famous for Toy Story, so he must be a cuddly, harmless artist; the black-humored Steely Dan jammed with jazz legends and projected laconic cool, so they must be a yuppie-friendly yacht-rock act.

As for the erudite Tull, perhaps their theatrical goofiness and "Dungeons & Dragons"-style album art backfired in that department. But they've always had bigger fish to fry than being cool. Leave your preconceptions at the door, maybe hop around on one foot a little, and you're in for musical treasures galore — from poetic outpourings to horny musings to sober inquiries into a higher power.

These days, Anderson is the only remaining original member of Jethro Tull. They've had numberless lineups across the decades, and longtime, fan-favorite guitarist Martin Barre left in 2011. But if the patina of The Zealot Gene is any indication, still more captivating work may lie ahead of Anderson and his cohorts — even with their best-known music a half-century behind them.

In the latest edition of Songbook, GRAMMY.com rings in the impending release of The Zealot Gene with a deep dive into every album from the band's still-underdiscussed discography — from their blues-rock beginnings to the folk trilogy to their work in the 21st century.

(Editor's note: This list focuses on the core Jethro Tull discography and excludes compilations and Anderson's solo albums.)

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images

Named after an 18th-century agriculturist, Jethro Tull began as a fairly typical blues/rock combo with one important distinction: the flute.

This Was (1968)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//6dPsGwnsdtk' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Jethro Tull's debut is less the vision of Anderson than of their original lead guitarist, Mick Abrahams, who appeared on a grand total of one record — this one.

A mostly straightforward blues/rock album, This Was features an instrument that immediately distinguished Tull from their peers. (Try and guess which one.)

This was intentional on Anderson's part. In a British rock scene with a preponderance of white-boy guitar shredders, Anderson demurred and took a different tack.

"I wasn't sure when Ian turned up with the flute," Tull's drummer at the time, Clive Bunker, said in their 2019 oral history The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I said, 'Look, Ian, it's a blues band, not a jazz band.'"

The eccentric Anderson stood out in other ways, too. "Ian was a good performer, but he was a strange man and I was confused," Abrahams recalled in the same book. "I remember seeing him shambling down the street wearing an old shabby overcoat, hair and beard all over the place, carrying a toilet bowl he'd pinched from the Savoy cinema."

As creative partners, the open-minded Anderson and blues-purist Abrahams weren't to be, but the one album they made together is a low-demand pleasure — and an enjoyable product of its time and place.

This especially goes for the rollin'-and-tumblin' "My Sunday Feeling," and "Dharma for One.” The latter features an invented "claghorn" — an amalgam of an ethnic bamboo flute, the mouthpiece of a saxophone and the bell of a child's trumpet.

The most well-known tune here is "A Song for Jeffrey," a harmonica-driven tribute to future Tull bassist Jeffey Hammond that doubles as a roast (before Hammond officially joined the band, he and Anderson were classmates). "Gonna lose my way tomorrow/ Gonna give away my car," Anderson sings. "Can't see, see, see where I'm going."

But Anderson had a pretty good idea of where he was headed — as foreshadowed by that rearview mirror of a title.

Stand Up (1969)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//MkF_dn3ni5g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

By 1969, Abrahams was out of the band. And in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, Anderson claims the pair were “never close,” noting his diametrically opposite nature: "I wasn't one of the lads. I didn't drink beer or smoke marijuana and hang out."

Barre soon replaced Abrahams; he would stay in the band for decades and perform on their most beloved works. And from the outset, he proved himself to be as eclectic and open-minded as Anderson needed him to be.

"Martin Barre wasn't a blues guitarist like Mick Abrahams," Anderson noted in the book. "I could see the possibilities."

With a simpatico co-pilot on board, Tull recorded their first truly excellent album — one that acts as a Rosetta Stone for their output throughout the following decades.

Barre's scorching lead parts on "A New Day Yesterday" foreshadow the mighty Aqualung, a jazzy rendition of Bach's "Bourée" displays their high-minded purview, and the international flavor of "Fat Man" gestures toward their '90s embrace of global sounds.

"It's progressive in that it reflects more eclectic influences, bringing things together and mixing and matching and being more creative," Anderson told Louder Sound in 2018. "For me, it's a very important album — a pivotal album."

Benefit (1970)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//9OZMgUu3B9s' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

An album borne of exhaustion with the touring lifestyle, Benefit introduced an anxiety and ache to Tull's sound — a vibe that would take flower on Aqualung. The songs also became slippier, more mysterious, more elliptical — partly thanks to a key influence in an English progressive folkie.

"Roy Harper, who I came to know quite well, wrote songs that were so personal and frighteningly intimate," Anderson noted in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I found it fascinating being drawn into this sexual intimacy, but having no idea who the other person in the song was."

This vibe made it into songs like "Alive and Well and Living In," which obscures its subject: "Nobody sees her here/ Her eyes are slowly closing," "If she should want some peace, she sits there without moving/ And puts a pillow over the phone."

Elsewhere, "Sossity: You're a Woman" is their first knockout acoustic ballad in a career full of them. (Honestly, if you only seek out Tull's quieter selections, you'll still find the essence of the band.)

But most telling of all is "For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me." The track was inspired by astronaut Collins, who remained in the command module of Apollo 11 as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked the lunar surface. (Advertently or not, that sums up the loneliness of touring life.)

Despite intriguing moments like these, Benefit mostly functions as the connective tissue between two eras of Tull and the ramp-up to a stone-cold classic.

Photo: Michael Putland via Getty Images

Jethro Tull's sound became increasingly dynamic and diverse, dealing in themes including organized religion. On successive releases, their ambition only grew more outsized.

Aqualung (1971)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//61PMgwdGOQg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

If you can believe it, Tull's signature song, “Aqualung,” contains no flute. But it contains more than most give it credit for — an ocean of pathos.

Atop Barre's six-note thunderclap of a riff, Anderson snarlingly describes the titular, itinerant character, who wanders the frigid streets in raggy threads, leering at neighborhood girls.

If that was all "Aqualung" was, though, it wouldn't be much — a sudden dynamic shift into a hushed, acoustic ballad goes for the heart. Instead of judging the pathetic vagabond, Anderson notes his loneliness, isolation and marginalization. Most touchingly, he addresses him as "my friend."

"[I was] not trying to imagine much about his life, but more in terms of our reaction to the homeless," Anderson told GRAMMY.com in 2021. "I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel — compassion, fear, embarrassment."

After that momentous introduction, Tull leads listeners through an astonishing song cycle about the rot of organized religion ("My God"), domestic tranquility ("Wond'ring Aloud") and the dangers of overpopulation ("Locomotive Breath").

"'Locomotive Breath' was incredibly difficult to do," Anderson recalled in the oral history. "You have to keep the lid on the thing, like a boiler building up pressure."

Aqualung crescendos with perhaps the most powerful song ever written about the difference between God and church: "Wind Up," where the Highest addresses Anderson directly. He's a personage with thoughts and feelings, He informs Anderson — not just on Sunday morning, but 365 days per year.

In the bridge of "Wind Up," Anderson's incredulity and rage say it all. While he says his spiritual beliefs haven't changed since 1971, his rejection of dogma only seems to stoke his fires as a seeker of truth.

Thick as a Brick (1972)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//9jNLYCudQW4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Is there any more tired rock-critic construction than the "concept album"? Back in 1972, Anderson didn't seem to think so.

"I figured … that I'd give people the mother of all concept albums," he said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, "by taking the mickey out of some of our peer group who were now doing concept albums that were overblown and silly." (Genesis and Yes, he was looking at you.)

Thus was the impetus for Thick as a Brick, which Tull originally released as one 43-minute song across two sides. After the umpteenth shifted meter and goofy breakdown, the gag wears somewhat thin across its runtime — even with lovely moments sprinkled throughout, like the "Poet and the Painter" section.

But its flaws takes nothing away from the album's sublime first movement, titled "Really Don't Mind” in a 2015 remix and remaster. Seemingly taking shots at intellectual elitism and a drain-circling culture, it’s one of the clearest available windows into Anderson's worldview.

"The sandcastle virtues are all swept away," he warns, "in the tidal destruction/ The moral melee." And if only for the radiant and pointed three minutes that open the record, Thick as a Brick belongs in any rock fan’s collection.

A Passion Play (1973)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//-z0MvdOdV3Y' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

By far, the most priceless take on A Passion Play comes from a Melody Maker clip about a Wembley concert, where Tull played this baffling, colossal suite front to back. Think Thick as a Brick but even more scattered, with Anderson skronking on the saxophone throughout.

"The lyrics or story of A Passion Play did not communicate one whit," journalist Chris Welch wrote, horrified, in a piece headlined "Crime of Passion." Even more dramatically, "After the show, I felt uncomfortable and filled with inner torment."

An ambitious program about an afterlife-dweller accompanied by a bonkers stage show upon its release, A Passion Play is a head-scratcher — and its creator admits it.

"I didn't practice enough, I wasn't trained, and it hurt my lip," Anderson admitted in the oral history of his questionable sax chops, calling A Passion Play "in the bottom third of Jethro Tull albums." (Elsewhere, he called it "the step-too-far album.")

Are there decent moments? Sure, like the relieving appearance of acoustic guitar in "The Silver Cord" and "Overseer Overture," and the percolating ending of "Memory Bank."

But at the end of the day, if you're looking for Extravagant Tull, there are more effective places to start.

War Child (1974)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//S5D9HZyYI6g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Written for a film that would never be made, War Child is a scaled-back, middle-of-the-road entry before five superb albums in a row. While Anderson himself called it "the last multiple outing of the dreaded saxophone" and "kind of OK," it offers three all-timers on Side 2.

First, cue up the gorgeous "Skating Away (On the Thin Ice of a New Day)," a xylophone-buoyed ode to the fragility of life. "Bungle in the Jungle" — which views citydwellers through a zoonotic lens — remains one of the band's biggest radio hits.

Another for your ongoing Acoustic Tull playlist is "Only Solitaire," which marries a gently winding melody with a lyrical purview that's acrid even for Anderson: "Brain-storming, habit-forming, battle-warning, weary winsome actor/ Spewing spineless, chilling lines."

Minstrel in the Gallery (1975)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KSqnqjLI5Dc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Finally: a worthy follow-up to Aqualung.

Recorded with a mobile studio in Monaco, Minstrel in a Gallery elegantly splits the difference between multifarious heavy rock (the title track) and string-swept balladry (almost everything else), with an unwavering eye for dynamics and atmosphere.

Its creator called it "an angrier record" and its sessions as "a little divisive"; Barre didn't see it that way. "Ian was at his writing peak on Minstrel," he said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I don't recall any friction at all. It's just that Ian took it very, very seriously."

Anderson's single-minded vision paid off in some of his loveliest songs to date. "Cold Wind to Valhalla" is a Norse daydream where "breakfast with the gods/ Night-angels serve with ice-bound majesty." "Baker St. Muse," for its part, is a gorgeous suite about quotidian London scenes.

But then, oh: the time-capsule track. "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All," a heartstopping acoustic serenade suggestive of packing and leaving, remains one of Anderson's grand slams and potentially the most bewitching tune in the Tull songbook.

A puzzle as much as a song, this darkly seductive masterwork is less listened to than communed with — preferably in solitude, deep into the night.

Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! (1976)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//wt4RA2hHoRA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Initially conceived as a stage musical, Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! follows a washed-up character who learns lessons about youth and rebirth and nostalgia… or something. But the real hero of this story is the mixing and mastering engineer Steven Wilson.

Here’s why Wilson, who has remixed and remastered many Tull albums by now, is a magical being. What everyone thought was a just-OK Tull album, he revealed to be nearly perfect. As it turns out, the original mix was just murky enough to dull the album’s impact.

In Wilson's hands, Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll isn't just saved; it's potentially the most accessible gateway to this band. Shone until they gleam, "Salamander," "Bad-Eyed and Loveless" and "Pied Piper" contain sneaky hooks that might burrow into your consciousness.

While the cornerstones of the album might be the triumphant title track and closer, "The Chequered Flag (Dead or Alive)," the finest of them all is a very deep cut: “From A Dead Beat to an Old Greaser.”

Climbing a stair-step melody with an exquisite string arrangement, this affecting hipster tableau name-drops Charlie Parker, Jack Kerouac and René Magritte as it builds to a lithe sax solo.

Photo: Stan Frgacic/Corbis via Getty Images

Using pastoral instrumentation as a canvas, Ian Anderson explored themes of agriculture, woodland mythology and the environment under siege.

Songs From the Wood (1977)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//_XM-u9jBsMs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Spurred by the book Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain and a relocation to the Buckinghamshire countryside, Songs From The Wood is a jolly, earthy affair preoccupied with the pre-Christian old gods and all things verdant and growing.

Still, a faint thread of anxiety runs throughout, as if Anderson is clinging to the old country as it fades.

"Does the green still run deep in your heart/ Or will these changing times, motorways, powerlines keep us apart?" Anderson asks of the titular, woodland character in "Jack-in-the-Green." (Think Radagast, the wizard of nature from Tolkien's works — but small enough to drink from an “empty acorn cup.”)

Songs from the Wood isn't perfect — Side 2’s seemingly endless, guitar-squealing “Pibroch (Cap in Hand)” is seemingly included here to run the clock. Still, the litany of folky gems throughout makes it a top-shelf Tull offering.

From the springy "Cup of Wonder" to the wintry delight "Ring Out, Solstice Bells" to the randy "Velvet Green," Songs from the Wood exudes giddy, punch-drunk joy at the gift of the green country.

Heavy Horses (1978)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//7Pq55hLi6VM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Sure, songs about broken guns and hunting clothes and making love in the woods are all well and good. But on Heavy Horses, Tull took the theme further by zeroing in on animals — several songs roughly correspond to a critter found in the English countryside.

It all kicks off with "...And The Mouse Police Never Sleeps," the most deliciously bloody toast to the housecat this side of T.S. Eliot. To wit: "Savage bed foot warmer/ Of purest feline ancestry… With claws that rake a furrow red/ License to mutilate." If that doesn't sum them up, what does?

Powered by the kinetic rhythm section of bassist John Glascock and drummer Barriemore Barlow, Heavy Horses only gains steam as it hits gem after gem. "Moths" is an oblique love story imbued with magical realism; the majestic, nine-minute title track laments the obsolescence of workhorses amid the encroaching industrial age.

The crown jewel, though, is "One Brown Mouse," a rapturous ode to the banalest of household pests with a dizzying, key-toggling bridge. Drop every one of your defenses, and the song a rush of unadulterated feeling; it will pry open your heart if you let it. Smile your little smile.

Stormwatch (1979)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//M1ivxxPISZc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

With country air behind Tull, something wicked this way came. Stormwatch flips the script on its (mostly) carefree predecessors, zeroing in on weather and the environment. Appropriately, the music sounds salty and eroded, like a schooner battered by a tempest.

After the opener "North Sea Oil” needles the petroleum business, the fraught vibe only unspools from there. In "Orion," Anderson addresses the titular constellation as it indifferently observes the world’s dramas; in "Something's On The Move," he tackles climate change decades before Greta Thunberg.

Sure, it’s all a touch dreary and monochromatic, but that’s part of its charm: Stormwatch is a rock-solid Tull album with a vividly rendered moral compass.

The power ballad "Home," with guitar-monies beamed overhead like the Aurora Borealis, stands out in particular. So does the weatherbeaten ballad "Dun Ringill" — which, with its disembodied, spectral whispers, sounds like a dispatch from Davy Jones' Locker.

Photo: Pete Cronin/Redferns

At the top of the 1980s, Tull sensed the winds of change and interwove synthesizers into their sound.

A (1980)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KLiNxL7RrcQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Is it jarring to see Jethro Tull playing synth-inflected music in jumpsuits? That’s fair: A was never meant to be a Tull album, but — hence the initial in the title — an Anderson solo album. hence the title. But thire record label, Chrysalis, didn't think it would sell under his name.

"Barrie, [keyboardist] John Evan and I all received the same, cheap carbon copy of a letter explaining that the record company had decided to release Ian's latest recordings as a Jethro Tull album," synthesist and arranger Dee Palmer said in the oral history. "Our services were no longer required."

This, along with other factors, led to upheaval within the camp and the departure of multiple members. Taken together, these factors make A an odd duck in the catalog, but listening today, it's by no means an embarrassment.

Thanks in no small part to its remaster — thanks again, Steven Wilson — songs like "Crossfire," "Fylingdale Flyer" and "Protect and Survive" show that Anderson's pop instincts remained undimmed, no matter the aesthetic or context.

Plus, it ends with two great, underdiscussed tunes — the giddy instrumental workout "The Pine Marten's Jig" and capacious closer "And Further On."

The Broadsword and the Beast (1982)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//yvHPaRGcv8g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

While synths occasionally trapped A in amber; they're woven in far more seamlessly on its follow-up. "We took the new technology and married it with folk-rock," Anderson explained in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, calling it "a good album and full of light and shade."

Indeed, The Broadsword and the Beast is a welcome return to form, with synth textures adding vividness and color to the songs. Despite tanking in America — probably due to the very non-single title track being the single — the record fits snugly with their '70s masterworks.

From the feisty "Beastie" to the irresistible "Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow," excellent tunes abound here. But the inarguable centerpiece is "Jack-A-Lynn": a downcast acoustic ballad studded by a melancholic synth motif and, eventually, detonating into stadium rock.

Under Wraps (1984)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//eo9fJO8JD5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Speaking of the 1980s, "I don't think Ian should have ever attempted to keep up with the modern trends," then-bassist Dave Pegg said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. ("But he wasn't alone — everybody else was doing it too,” he qualifies.)

This seems to sum up the problem with the leaden, electronics-heavy Under Wraps. While the majority of tracks, like "Lap of Luxury," "European Legacy" and "Saboteur," are probably best left uninvestigated, there's one decent tune here — and one gorgeous one — to add to circulation.

Respectively, those are "Paparazzi" — which actually does something angular and intriguing with the dated palette — and "Under Wraps #2," which strips down the instrumentation for a sweet, simmering love song with charming call-and-response verses.

Crest of a Knave (1987)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//LySTISqaH9o' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Crest of a Knave may be one of Tull’s most surprising and thrilling returns to form, but its reputation precedes it in a different way.

Sadly, it's forever tethered to the upset at the 1989 GRAMMY Awards, where it beat Metallica's …And Justice For All in the Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance category. (Afterward, Anderson took out a full-page Billboard ad, which simply read "The flute is a heavy, metal instrument.")

At this point, however, it's time to consider Crest of a Knave apart from this well-worn anecdote. Fact is, it may be Tull's final truly great album until The Zealot Gene more than 30 years later.

The album begins thrillingly with the vertiginous "Steel Monkey," where a knuckleheaded skyscraper worker tries to get fresh with a woman. The obviously sequenced synths and programmed drums don't stifle the tune one iota — true to the industrial theme, they make it pump and slam like hydraulics. As Anderson's character gloats about his high-flying lifestyle, a skyward key change puts you right there — 300 feet above the ground.

Elsewhere, "Farm on the Freeway" addresses infrastructure's threat to American farmers, and "She Said She Was a Dancer" sardonically casts Anderson as an out-of-his-depth Western rocker trying to pick up an Eastern European.

Despite its very 1987 production, Crest of a Knave is a triumph purely on its own terms.

Photo: Martyn Goddard/Corbis via Getty Images

While grunge reigned in the '90s, Tull returned to their heavy-blues roots and branched into global sounds.

Rock Island (1989)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//cKhw2H8jaic' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Like A Passion Play and Under Wraps before it, Rock Island could probably vanish from the catalog without altering the narrative. Which doesn't make it bad, exactly — save for the wince-worthy sexual innuendo of "Kissing Willie."

Anderson has publicly expressed fondness for at least three tunes. In the oral history, he praised "The Whaler's Dues," which he praised as "representing something that had happened historically but still had some relevance today"; and closer "Strange Avenues," which he called a "very spooky, moody piece of music."

In Silent Singing, he cited "Another Christmas Song" as "probably my long-term favorite, oozing nostalgia, reflection, and dislocated family relationships.”

But after you throw those tunes on your Tull playlist, seek out Rock Island's follow-up, Catfish Rising, for a far more engaging example of what the band could do at the close of the '80s.

Catfish Rising (1991)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//lj0IV9ZTVnU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

That's more like it: Catfish Rising was Tull's richest, loamiest album since Crest of a Knave.

A return to ballsy hard rock in the ballpark of Stand Up, Catfish remains strangely overlooked in the oeuvre. It's the moment they emerged from the miasma of the '80s, happily remembering what made them special in the first place.

This doesn't just mean 12-bar shuffling — although "Still Loving You Tonight" is a decent throwback in that regard — but outfitting that palette with acoustic instruments like mandolin and mandola, which has always been Tull’s specialty.

Despite not containing their deepest material, Tull listeners should know a few selections on Catfish Rising: "Sparrow on the Schoolyard Wall," "White Innocence" and "Gold Tipped Boots, Black Jacket and Tie," to name a few.

Even while miles away from the heights of Aqualung and Minstrel in the Gallery, returning to the blues’ gravitational center kept Tull healthy and robust into the '90s.

Roots to Branches (1995)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//VN8VJp8Gdn4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Could Tull have successfully drifted into the remainder of the '90s as a new-age band with a Middle Eastern tint, like latter-day Popol Vuh? Roots and Branches makes a compelling case for that direction.

For once, the songs are secondary to the feeling: Roots to Branches captures the specific moment where classic rockers made "exotic" works during the CD reign. With each synth sweep and reverberated sidestick, the humid-rainforest vibe deepens.

While the album contains more ambiance than anything, a few gems reveal themselves with time — such as the Arabic-influenced ode to jewelry, "Rare and Precious Chain" and the atmospheric, after-hours piano ballad, "Stuck in the August Rain."

Altogether, though, Roots to Branches is one for deep heads, not neophytes. (Unless "dreamily dated" is your jam — in that case, fire it up.)

J-Tull Dot Com (1999)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//gOqUvK9ZvSg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

From the title to the typography to the too-anatomically-correct album art of the Egyptian god Amun, J-Tull Dot Com can be a tough one to defend at first. But if you can get past the packaging, there's very little actually wrong with the album — well, other than "Hot Mango Flush."

The skulking "Hunt By Numbers" is another one of Anderson's (always welcome) songs about cats. Following that is the beguiling "Wicked Windows," which may be the only song ever written about eyeglasses — and despite the stilted drum production, it’s an imaginative beauty.

Named after the band's first registered website, "We did it in my studio and we rehearsed it and played it live in the same way as we did Thick as a Brick,” Anderson explained in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "J-Tull Dot Com had a high-tech title but was relatively low-tech music."

With that clarification in mind, feel free to find a used copy and party with Amun. Still, there are so many worthy alternatives — especially for first-time listeners.

The Jethro Tull Christmas Album (2003)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//GCkOKhCEQNw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

What would be Jethro Tull's final album for 18 years —Anderson released solo albums Homo Erraticus and Thick as a Brick 2 in the interim — wasn't really a collection of new material. Rather, it contains re-recordings of old songs and variations on Christmas classics, like "God Rest Ye Merry Gentleman."

If you're a committed fan who needs a little yuletide Tull, it'll do in a pinch. For everybody else, The Jethro Tull Christmas Album is mostly worth hearing for the lovely, updated versions of oldies "A Christmas Song" and "Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow."

Photo: Ricardo Rubio/Europa Press via Getty Images

After time off from the name and the departure of longstanding guitarist Martin Barre, Anderson and his latest cohorts have made a triumphant Tull album.

The Zealot Gene (2022)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://open.spotify.com/embed/track/1IhW1JjA4A8euFYXV2swU5?utm_source=generator' width='100%' height='380' frameBorder='0' allowfullscreen='' allow='autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; fullscreen; picture-in-picture'></iframe></div>

Even though Anderson's never stopped recording and touring, it's bracing to hear the first music under the Jethro Tull name in ages.

Questions abounded upon its announcement: would it be a bunt, like J-Tull Dot Com, or a grand slam, like Crest of a Knave? Would the absence of Martin Barre diminish the music?

Fortunately, this lineup, which includes longtime bassist David Goodier and keyboardist John O'Hara, is as valid and robust as any before it. And the album they made together, The Zealot Gene, hits all the marks that make the band stupendous and singular.

For starters, Anderson is as literate and layered a lyricist as he ever was. Still, he's never out to merely flaunt his vocabulary (despite employing verbiage like "sacrum," "perfidious" and "rostrom"). There's a refreshing, human element to the songs, which pull from accounts as old as time to explain how our species got in such a mess.

In "Mine is the Mountain," the wrath of the God of the Pentateuch radiates — you feel His judgment. True to its roots in the erotic Song of Solomon, "Shoshana Sleeping" has an anticipatory, heart-racing quality. And "In Brief Visitation" flips the account of Christ's death into a meditation on the concept of "fall guys."

Just as happily, The Zealot Gene isn't an aural monolith, but something of a tour through Tull's various styles over the years. The harmonica in "Jacob's Tales" recalls This Was; the synths in "Mrs. Tibbets" recall Crest of a Knave; the acoustic suite near the end recalls Minstrel in the Gallery.

Seemingly galvanized by the finished product, Anderson is already writing another Tull album: "On the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse," he recently told GRAMMY.com. "That's partly wishful thinking, partly me putting myself on the spot."

Even after half a century, the minstrel has reams left to sing — and say.

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

From left: David Corio/Redferns; Paul Natkin/Getty Images; Scott Gries/Getty Images; Richard E. Aaron/Redferns

feature

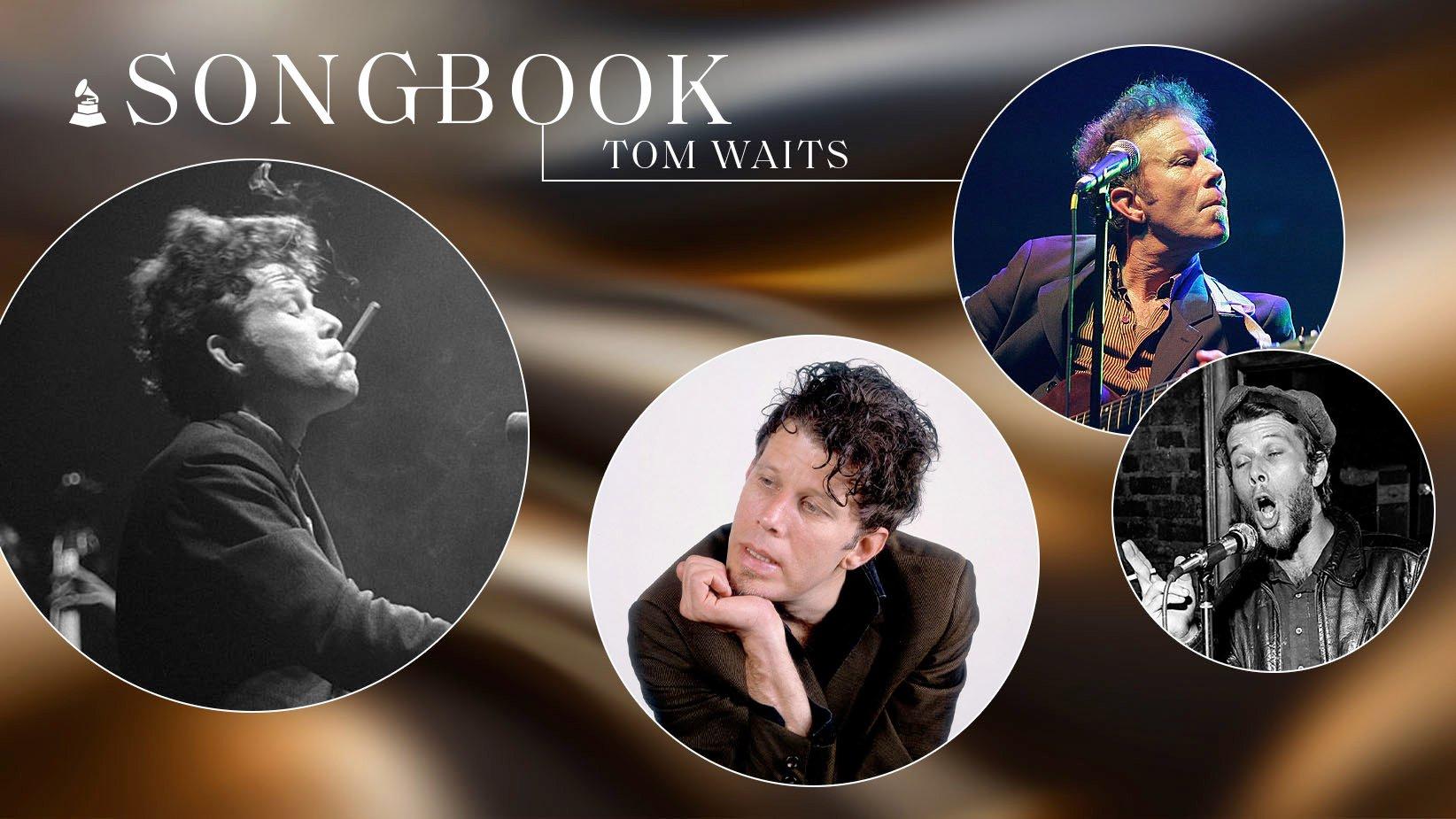

Songbook: A Comprehensive Guide To Tom Waits’ Evolution From L.A. Romantic To Subterranean Innovator

As Tom Waits’ series of Island Records releases from the ‘80s and ‘90s are being reissued, take an album-by-album trip through the legendary singer/songwriter’s significant body of work.

When Tom Waits warned on "Underground," the first song on his transformational 1983 album Swordfishtrombones, "there’s a rumblin’ groan down below," he very well could have been describing the artistic awakening that made him a legend.

Once an earnest yet good-humored singer/songwriter, Tom Waits is the rare artist in the past 50 years to successfully pull off something as radical as a complete artistic reinvention. A songwriter with a taste for the dark and grotesque as much as the theatrical, Waits has built up a catalog heavy on bizarre characters, morbid nursery rhymes, gruff junkyard blues and a uniquely unconventional take on rock music. And though it took some experimentation, trial and error and eventually getting married to arrive on the sound we hear today, he’s made a five-decade career of embracing sounds on the fringe and turning them into memorable melodies.

A Southern California native who got his start playing folk clubs in San Diego before relocating to Los Angeles in the 1970s, Tom Waits debuted as a relatively conventional singer/songwriter with a twinge of blues and jazz in his bones. And where his earliest records found him singing with more of a raspy croon, he adopted a vocal growl more spiritually akin to Louis Armstrong and Captain Beefheart.

Waits never quite fit in alongside peers such as Jackson Browne or James Taylor. His instincts often pushed himself somewhere a little dirtier and darker, favoring tales of vagabonds and outcasts told with an inebriated sentimentality and irreverent humor. Throughout his decades-long career, the two-time GRAMMY winner never let go of the emotional honesty in his songwriting.

Waits has joked that he makes two types of songs: grim reapers and grand weepers. The former became his staple sound in the 1980s after he married longtime creative partner Kathleen Brennan and began his decade-long tenure on Island Records, which still occasionally found him returning to the latter via less frequent but no less disarming ballads.

What once was a songbook reflective of the bars and familiar streets evolved into surreal dens of iniquity and theaters of the grotesque. Waits' knack for storytelling and character development only strengthened over the years, even as his songs took more oddball and ominous shape. Swordfishtrombones' "Sixteen Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six" follows a hunter following a crow into a Moby Dick-like epic; spoken word standout "What’s He Building In There?," from 1999’s Mule Variations, prompts the listener to ponder who’s really up to no good.

Though his record sales have been modest, Waits' songs have been covered by the likes of Rod Stewart and Eagles, and he’s collaborated with everyone from Bette Midler to Keith Richards. His songwriting and unique musical aesthetic have influenced records by Andrew Bird, Neko Case, Morphine and PJ Harvey.

As Waits’ acclaimed series of albums on Island Records from the ‘80s and ‘90s are being reissued in remastered form — some for the first time on vinyl in decades — GRAMMY.com revisits the legendary singer/songwriter’s significant body of work via each of his studio albums. Press play on the Spotify playlist below, or visit Apple Music, Pandora, and Amazon Music to enter Waits' sonic wonderland of '70s era ballads and his plethora of twisted narratives and experimental sounds.

The Barroom Balladeer

Though often treated to his own idiosyncratic filter, Waits’ early output in the ‘70s reflected the glamor and sleaze of his Los Angeles surroundings.

Closing Time (1973)

Making his debut at the height of the ‘70s singer/songwriter boom, Tom Waits revealed only slight glimpses of his myriad idiosyncrasies on 1973’s Closing Time. Heavily composed of ballads, the album’s sound is a result of a compromise between Waits’ own preference for more jazz-leaning material and producer Jerry Yester’s penchant for folk.

Despite, or perhaps because of, that creative tension, Closing Time has a unique character. A sense of wanderlust and escape within its 12 piano-based songs feels like a jazzier, West Coast counterpart to Bruce Springsteen. Waits imbues the call of the road with a sense of melancholy on gorgeous opener "Ol’ 55" and gives a hefty tug at the heartstrings on the aching "Martha." He kicks up the tempo on "Ice Cream Man." Closing Time is often at its best when it’s more quietly haunting, like on the bluesy "Virginia Avenue."

Though the album didn’t initially garner much critical or commercial attention, it’s since become regarded as one of the finest moments of Waits’ early recordings. It also quickly earned the respect and admiration of other artists, with various songs from Closing Time being covered by Bette Midler, Eagles and Tim Buckley.

The Heart of Saturday Night (1974)

After establishing himself with the romantic ballads of his debut album, Waits waded deeper into the waters of boho jazz and beat poetry in its follow-up, The Heart of Saturday Night.

Waits shares his perspective from the piano bench and the barstool, occasionally delving into a sing-speak delivery against upright bass and brushed-drum backing. Throughout, Waits serves up colorfully embellished imagery about nights on the town and getting soused on the moon. Though not as experimental or sophisticated as some of his later recordings, The Heart of Saturday Night nonetheless finds Waits in a more playful mood, more overtly showcasing his sense of humor and penchant for a particular kind of down-and-out protagonist. Fittingly, the album's title track was directly inspired by Jack Kerouac.

The Heart of Saturday Night is somewhat autobiographical in that it’s one of the few albums that repeatedly features references to his youth growing up in San Diego. Most famously on "San Diego Serenade," as well as in his narrative of driving through Oceanside in "Diamonds on My Windshield," and his name-drop of Napoleone’s Pizza House, the pizzeria in National City where he worked as a teenager, in "The Ghosts of Saturday Night."

Nighthawks at the Diner (1975)

As Tom Waits further established himself as a singer/songwriter more at home in the naugahyde and second-hand smoke of a seedy nightclub than a folk festival, he sought to replicate the atmosphere of a jazz club on his third album. It’s not a live album in a literal sense; Waits invited a small crowd into the Record Plant studio in Los Angeles on two nights in July of 1975, and though the venue is artifice, the crowd reactions are genuine.

More heavily rooted in jazz than Waits’ first two albums, Nighthawks at the Diner mostly follows a particular pattern: An "intro" track featuring some witty barfly banter, followed by an actual song. Introducing each song with a round of inebriated wordplay ("you’ve been standing on the corner of Fifth and Vermouth," "Well I order my veal cutlet, Christ, it just left the plate and walked down to the end of the counter…") is a bit of a gimmick, yet for all its loose, freewheeling feel, the album features some of his best early songs, including "Eggs and Sausage," "Warm Beer and Cold Women" and "Big Joe and Phantom 309."

Releasing a manufactured live album early on proved a canny gambit for Tom Waits and resulted in his highest charting album up to that date. And it’s easy to see why: Nighthawks showcased the raconteur persona that’d come to define much of Waits' work to come.

The Bluesy Bohemian

Embracing a grittier sound and a more character-driven approach to storytelling, Tom Waits entered a period of creative growth in the second half of the ‘70s that saw him balancing a darker tone with a wry sense of humor.

Small Change (1976)

On his second and third albums, a jazz influence and increasingly prominent humor saw Waits developing not just as a distinctive personality, but as a character. His raspy growl deepened onSmall Change, as Waits' barfly persona finds himself in increasingly seedier surroundings. This new area is best showcased through the amusingly unsexy striptease scat of "Pasties and a G-String" and the surreal and misty eyed "The Piano Has Been Drinking."

Small Change isn’t nearly as jokey as the previous year’s Nighthawks at the Diner, but Waits carries a persistent smirk as he rattles through a laundry list of hucksterish advertising slogans in the carnival-barker beat jazz of "Step Right Up": "It gets rid of unwanted facial hair, It gets rid of embarrassing age spots, It delivers the pizza." He even ramps up an element of danger in the noir poetry of "Small Change (Got Rained on With His Own .38)".

Still, the heartache and romance remains within the album’s best ballads, including the gorgeous opener "Tom Traubert’s Blues" and the imagined depiction of a lonely waitress in "Invitation to the Blues."

Foreign Affairs (1977)

Tom Waits’ fifth album Foreign Affairs unexpectedly became one of his most consequential releases.

A rare Waits album that opens with an instrumental ("Cinny’s Waltz"), Foreign Affairs finds him taking on more narrative driven songwriting, as in the lengthy noir tale of "Potter’s Field" and the nostalgic road-movie recollection of "Burma-Shave." It seems fitting that this is the moment where Hollywood began to crack a door open for Waits — these songs sound like they were made for the silver screen.

Indeed, album standout "I Never Talk to Strangers," a duet with Bette Midler, inspired Francis Ford Coppola’s 1981 film One From the Heart. Waits wrote and performed on its soundtrack, and would work with Coppola multiple times.

Blue Valentine (1978)

Parallels between Waits' music and his acting career crop up throughout , beginning with 1978’s Blue Valentine. Released the same year that he made his acting debut in Paradise Alley — cast as a piano player named Mumbles, an apt role to be sure — Blue Valentine opens with a big, cinematic number itself, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s "Somewhere," the famous ballad from West Side Story.

Blue Valentine also finds Waits in character development mode, increasingly populating his bluesy and bedraggled songs with widows and bounty hunters, night clerks and scarecrows wearing shades. It also features one of his most heartbreaking songs in "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis," in which Waits’ first-person epistle comes from the voice of the title character who reaches out to an old friend in a hopeful and warm update on the changes she’s made for the better. And then he seamlessly, devastatingly pulls out the rug from underneath it all, as only a fabulist like Tom Waits can.

Heartattack and Vine (1980)

The transition from one decade to the next couldn’t have been starker for Tom Waits as he entered the 1980s. His final album for Asylum Records seemed to signal a sea change, with its leadoff track steeped in scuzzy, distorted guitar and gruff blues-rock rather than piano balladry, jazz and beat poetry.

Heartattack and Vine is in large part more of a proper rock record than any of Waits’ earlier albums, as he lends his husky growl to gritty songs such as "Downtown" and "In Shades." Still, it’s the most tender moments that comprise some of Heartattack and Vine’s most enduring songs, such as "On the Nickel" and, in particular, "Jersey Girl," covered four years later by the Garden State’s own Bruce Springsteen.

The Avant-Garde Auteur

Tom Waits underwent a significant transformation in the 1980s, mostly leaving behind the smoky jazz-club ballads of the ‘70s in favor of a more avant garde take on rock music, rife with an arsenal of unconventional instruments.

Swordfishtrombones (1983)

The most dramatic shift in Tom Waits’ career came with the release of 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, his first release for Island Records and the first album of what came to be the sound most often associated with Waits. It’s rougher, rawer, more experimental and offbeat. A great deal of the credit goes to Waits’ wife, Kathleen Brennan, who introduced him to artists like Captain Beefheart and who became his creative partner, co-writing many of his best-known songs.

Waits trades the piano and strings of his earlier material for arrangements better fit for junkyard jam sessions and New Orleans funerals. Though he’s delivered a long list of releases that have since usurped such a title, Swordfishtrombones certainly sounded like his weirdest album at the time. Very little of it sounded like a conventional pop song;it’s interwoven with spoken-word pieces both hilarious and unnerving ("Frank’s Wild Years," "Trouble’s Braids"), instrumentals ("Dave the Butcher," "Rainbirds"), boneyard bashers ("Underground," "16 Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six") and even a few tender ballads ("Johnsburg, Illinois," "Town With No Cheer").

Though arguably far less commercial than anything he’d released prior, Swordfishtrombones still cracked the bottom half of the album charts. It also received the attention of critics, who praised Waits’ bold new direction and unconventional stylistic choices.

Rain Dogs (1985)

For much of the 1970s, Tom Waits took inspiration from the seamier side of Los Angeles, with occasional sentimental nods to his youth further south along Interstate 5 in San Diego. With 1985’s Rain Dogs, however, he relocated to New York City to capture an even grimier and grittier album inspired by its outcasts and outlaws.

Recorded in what was then a rough part of Manhattan in 1984, Rain Dogs continues the stylistic experimentation of Swordfishtrombones with an unusual array of instruments for a rock album, including marimba, trombone and accordion, the latter of which opens the title track in dramatic fashion with an incredible solo.

Rain Dogs also began Waits’ long collaborative relationship with Marc Ribot, whose guitar playing helps craft the album's signature sound. Through his Cuban jazz-inspired playing on "Jockey Full of Bourbon" and the scratchy and dissonant solo on "Clap Hands." Yet the album also finds him in the company of Keith Richards, whose licks appear on the album’s most famous song, "Downtown Train," which became a hit for Rod Stewart when he covered it in 1991.

Rain Dogs features Waits’ first co-writing credit from Brennan, brought dded gravitas to the aching ballad "Hang Down Your Head." It’s one of a few moments that cuts through the carnivalesque atmosphere of the album (see the demented nursery rhyme "Cemetery Polka," the crime-scene poetry of "9th and Hennepin" and the litany of misfortunes in "Gun Street Girl"). IRain Dogs is Tom Waits perfecting his approach, completing a stylistic transformation with one of his greatest batches of songs.

Frank’s Wild Years (1987)

One of the highlights of Waits’ 1983 album Swordfishtrombones was a humorous spoken-word jazz interlude wrapped up in a David Lynch nightmare, titled "Frank’s Wild Years," in which the titular Frank settles down into a suburban lifestyle, only to set his house on fire and drive off with the flames reflecting in his rearview mirror. Those 115 seconds or so were enough for Waits and Brennan to spin the idea out into a stage play, with this album serving as its soundtrack. (Its original cast at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre included Gary Sinise and Laurie Metcalf.)

Frank’s Wild Years likewise comprises songs performed in the play, though without the context of knowing its origins, it doesn’t so easily scan as a set of songs written for the stage. It continues the aesthetic vision that Waits pursued on his two previous Island Records albums, steeped in Weill-ian cabaret and mangled lounge-jazz renditions, like in the hammy Vegas version of "Straight to the Top." Waits continues to run wild stylistically, however, veering from junkyard blues-rock in opener "Hang On St. Christopher" to the tenderness of the lo-fi 78-style recording of closing ballad "Innocent When You Dream."

Fifteen years after its release, "Way Down in the Hole," was given a second life as the theme for the HBO drama "The Wire," each season featuring a different artist’s rendition of the song. Waits’ original scores the opening credits for season two.

Bone Machine (1992)

The title of Tom Waits’ tenth album fairly accurately sums up the sound of the record, which finds Waits incorporating heavier use of curious forms of percussion, many of them he played himself. Opening track "Earth Died Screaming" even resembles the sound of bones clanking against each other as Waits growls his way through an apocalyptic nightmare.

It’s fitting that Bone Machine coincided with Waits’ appearance as Renfield in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. A macabre sensibility and grotesque narratives permeate this record:Acts of violence become a form of entertainment in "In the Colosseum," and he retells an actual story of a grisly homicide in "Murder in the Red Barn." There’s levity too, like in the delusions of a fame-seeker in the rowdy "Goin’ Out West," which, along with half the songs on the album, was co-written by Brennan.

Eerie and macabre as Bone Machine is, it earned Waits his first GRAMMYAward, for Best Alternative Music Album in 1993. Likewise, the Ramones covered standout track "I Don’t Wanna Grow Up" three years later on their final album ¡Adios Amigos!; Waits repaid the favor in 2003 with a cover of the band’s "Return of Jackie and Judy."

The Storyteller’s Songbook

Deeper into the ‘90s and ‘00s, Waits became more active in writing music for the theatrical stage, albeit filtered through his own peculiar lens. He also closed out the ‘90s with his longest album, helping to usher in a late-career renaissance.

The Black Rider (1993)

The soundtrack to a theatrical production,The Black Rider closed Waits' tenure with Island Records with the soundtrack to a theatrical production. Though his music appeared in films by the likes of Jim Jarmusch and Francis Ford Coppola, and he entered the world of theater with Frank’s Wild Years, this was his released composed in collaboration with playwright Robert Wilson — they would work on three productions together — based on German folktale Der Freischütz. In fact, Waits affects his best German accent in the title track, in which he beckons, "Come on along with ze black rider, we’ll have a gay old time!"

Highlights "Flash Pan Hunter," "November" and "Just the Right Bullets" juxtapose distorted barks against ramshackle arrangements of plucked banjo, clarinet and singing saw. , The structure of the album — rife with interludes, instrumentals and reprises — sets it apart from any of his prior works, leaving room for the listener to fill in the visual blanks.

Mule Variations (1999)

The release of Mule Variations coincided with the launch of Anti- Records, an offshoot of L.A. punk label Epitaph that was more focused on legacy artists in a variety of genres. This also resulted in the unlikely instance of a song by Tom Waits appearing on one of Epitaph’s famed Punk-O-Rama compilations, which typically featured selections by the likes of skatepunk icons NOFX and Pennywise.

The longest studio album in Waits’ catalog, Mule Variations makes good on a six-year gap by being stacked with an eclectic selection of songs, most of them co-written with Brennan (who also co-produced the album). From the lo-fi beatbox bark that blows open the doors of leadoff track "Big In Japan," Waits essentially takes a tour through a disparate but cohesive set of songs that feels like a career summary, from tent-revival blues ("Eyeball Kid"), to devastating balladry ("Georgia Lee") and rapturous gospel ("Come On Up to the House").

A new generation of TikTok users received an introduction to this album via a meme featuring the album’s "What’s He Building In There?", an eerie spoken-word track from the perspective of a paranoid, busybody neighbor that became an unlikely viral sensation.

Blood Money & Alice (2002)

Another collaboration with playwright/director Robert Wilson, Blood Money and Alice were released on the same day in 2002. Co-written by Brennan, both are the soundtracks to two plays, the former based on an unfinished Georg Büchner play Woyzeck and the latter an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

Blood Money is darker and harsher in tone, kicking off with the satirically pessimistic "Misery is the River of the World," and featuring highlights such as the obituary mambo of "Everything Goes to Hell" and the charmingly tender "All the World Is Green."

Alice — whose songs had been circulated for years in bootlegs in rougher form — is more subdued and strange, its gorgeously lush and haunting opening ballad an opening into a head-spinning world of Lewis Carroll surrealism and disorientation. "Kommienezuspadt" soundtracks White Rabbit hijinks through German narration and Raymond Scott machinations, "We’re All Mad Here" lends a slightly darker shadow to an uneasy tea party, and "Poor Edward" diverts slightly from Carroll canon to visit the story of Edward Mordrake, a man born with a face on the back of his head.

The Catalog Continues…

Though Waits hasn’t been quite as prolific in the past two decades as he had been from the ‘70s through the late ‘90s, he continued to refine and evolve his strange and uncanny sound, while sharing a triple-album’s worth of rare material that offered a wide view of his evolution over the prior two decades.

Real Gone (2004)

Waits maintained his prolific streak with the lengthy Real Gone, which featured 16 songs and spans nearly 70 minutes — just a hair shorter than his longest, Mule Variations. It’s also the rare Tom Waits album to feature no piano or organ, its melodies primarily provided via noisier guitar from Harry Cody, Larry Taylor and longtime collaborator Marc Ribot, along with contributions from Primus bassist Les Claypool and Waits’ own son, Casey, who provides percussion and turntable scratches.

Real Gone is, at its wildest, the most abrasive record in Waits’ catalog, clanging and clapping and clattering through uproarious standouts such as the supernatural mambo of "Hoist That Rag," the CB-radio squawk of "Shake It" and creepy-crawly stomp "Don’t Go Into That Barn," one of his better scary stories to tell in the dark. He leaves a little room to ease back on dirges like the haunting "How’s It Gonna End" and the subtly gorgeous "Green Grass," but every corner of the album is populated by outsized characters and ominous visions that seem larger than ever.

Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers and Bastards (2006)

A career as long and fruitful as that of Tom Waits is bound to leave some material on the cutting room floor, the likes of which is compiled on the triple-disc set Orphans. Composed of non-album material that stretches all the way back to the 1980s, it’s divided into three distinctive themes: Brawlers, a disc of rowdier rock ‘n’ roll and blues material; Bawlers, a set of ballads; and Bastards, made up of what doesn’t fit into the other two categories — essentially Waits’ most fringe, peculiar music.

In drawing the focus toward each distinctive type of songs, Waits lets listeners experience more intensive, discrete aspects of his music. It’s the "Bastards," however, that tap into the extremes of Waits’ unique talents, comprising strange and macabre storytelling, unintelligible barks, even a wildly distinctive take on "Heigh Ho," from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Some of these songs had previously been released in some fashion — many of them appearing on movie soundtracks as well as collaborative efforts like Sparklehorse’s "Dog Door" — Orphans speaks to how productive he’s been over the past 40 years.

Bad As Me (2011)

Tom Waits’ final album (so far) hit shelves 12 years ago, the aftermath of which opened up his longest stretch without any new music since he began releasing records. Yet Bad As Me only offers the suggestion that Waits still has plenty of energy and inspiration left in the tank, as the album — released when he was 61 years old — comprises some of the hardest rocking material he’s ever committed to tape. It’s an album heavy on rowdy rock ‘n’ roll guitar, including that of Keith Richards, who had also previously lent his guitar playing to 1985’s Rain Dogs, as well as longtime collaborator Marc Ribot and Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo. Waits mostly adheres to concise, charged-up barnburners such as "Let’s Get Lost," "Chicago" and the more politically charged anti-war song "Hell Broke Luce." Though when Waits does ease off the throttle on songs like the eerie "Talking at the Same Time," the results are often spectacular.

If Tom Waits were to simply leave this as the end of his recorded legacy, it’d be a satisfying closing statement, though the closing ballad "New Year’s Eve" — ending on a brief round of "Auld Lang Syne" — would suggest new beginnings ahead of him. As it turns out, Bad As Me isn’t intended to be his last; earlier this year he confirmed that, for the first time in over a decade, he’s been working on writing new songs.

Songbook: A Guide To Wilco’s Discography, From Alt-Country To Boundary-Shattering Experiments

Photo: Assunta Opahle

feature

Ian Anderson Of Jethro Tull’s Themes & Inspirations, From 'RökFlöte' Backward

Jethro Tull's new album 'RökFlöte' is deeply influenced by old Norse paganism. And as per Ian Anderson's bank of lyrical concepts, it only scratches the surface.

Ian Anderson was finishing up an interview about the first Jethro Tull album in almost two decades, 2022’s The Zealot Gene, when he offered GRAMMY.com some tantalizing news: the next one would arrive sooner rather than later.

"At 9 o'clock on the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse," Anderson said two weeks before the end of 2021. "Should she decide to visit — hopefully, by 10 o'clock, I'll have the beginnings of some kind of flicker of an idea."

Where might Anderson, a voracious reader with a sweeping purview and a learned, gentlemanly air, go from there?

Fast forward to today, and we have the result: RökFlöte, which arrived April 21 and is based on "the characters and roles of some of the princip[al] gods of the old Norse paganism."

The GRAMMY-winning prog-rock heroes’ catalog has always been flecked with similar mythology, especially on 1977's fantastical, bucolic Songs From the Wood. But never had Anderson dedicated an entire album to this specific system of concepts.

RökFlöte’s opener, "Voluspo," is titled after the most famous poem in the Poetic Edda, which dates back centuries. Lead single "Ginnungagap" refers to the bottomless abyss that encompassed all things prior to the creation of the cosmos. "Ithavoll" is the meeting place of the gods.

This sheer depth of reference is not new for Anderson and company. A band less cited for their musical and philosophical depth than mined for cheap codpiece and Anchorman jokes, Jethro Tull contain multitudes just beneath the surface.

Take a stroll through the band's discography, and you'll find Anderson doesn't linger on one topic for long — and often addresses many concepts within the same album, or even song. Even Tull's most straightforward hits often contain richer meaning than what immediately meets the ear.

To celebrate the release of RökFlöte, here's a by-no-means-comprehensive breakdown of the poles Anderson and crew have tended to touch on throughout the band' almost 60-year career.

Love (With Some Caveats)

"I am a descriptive writer," Anderson wrote in the preface to his career-spanning compendium of lyrics, Silent Singing. "Not so often a storyteller, and almost never a heart-on-sleeve love-rat. Social documentary that you can hum along to."

True, this applies to the lion's share of his songs. But there are a couple of major exceptions — perhaps ones that prove the rule.

Take "Wond'ring Aloud," his gorgeous acoustic ballad on 1971's Aqualung that clocks in at less than two minutes. If there's any kind of social commentary or obscure meaning in "Wond'ring Aloud," it's difficult to tease out. Rather, the tune unfurls a quiet, domestic tableau of romantic bliss:

"Last night sipped the sunset/ My hand in her hair," he sings. "We are our own saviors as we start/ Both our hearts beating life into each other." The aroma of breakfast wafts through the kitchen; he considers their years ahead. Then, the unforgettable closing line: "And it's only the giving that makes you what you are."

Flash forward to "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All," another gobsmacking acoustic-with-strings centerpiece, from 1975's Minstrel in the Gallery.

Online chatter seems to suggest that the image of "one white duck on your wall" refers to a domestic split. Whatever the case, the darkly romantic song is suggestive of packing and leaving: "There's a haze on the skyline to wish me on my way/ There's a note on the telephone, some roses on a tray." From there, the song unfurls into a litany of images, commensurately puzzling and evocative — and full of arcane British-isms.

Like every other arena of life represented in Jethro Tull songs, romance comes with bottomless shades and nuances — and Anderson's seemingly attuned to the full spectrum.

Religion (As A Nonbeliever)

Jethro Tull classics that address faith, like Aqualung's "My God," "Hymn 43" and "Wind Up," excoriate religious corruption and dogma — to the degree that Anderson comes across as defensive of God.

"It's about turning God into a vehicle for personal power and the glitz and paraphernalia that sometimes surrounds religion," Anderson wrote of "My God" in 2019's oral history of the band, The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "It's actually quite pro-God in asking: 'People what have you done/ Locked him in his golden cage?'"

In "Wind Up," he rails: "I don't believe you/ You have the whole damn thing all wrong/ He's not the kind you have to wind up on Sundays." But it's crucial to stress that Anderson is decidedly not a man of faith.

Read More: Jethro Tull's Aqualung At 50: Ian Anderson On How Whimsy, Inquiry & Religious Skepticism Forged The Progressive Rock Classic

"I've learned to describe myself as somewhere between a pantheist and a deist," he wrote. "I'm not a Christian, but I like to do things for the church. I've always believed there are certain aspects of our society that, while anachronistic, are still worth preserving."

In an Olde English font in the Aqualung sleeve, Anderson printed a facsimile of Genesis 1:1: "In the beginning Man created God; and in the image of Man created He him."

Of the religious commentary scattered throughout Tull's discography, none seem to summarize Anderson's views like the above.

Nature (The Non-Human Kind)

Jethro Tull's so-called "folk trilogy" in the late 1970s — Songs From the Wood, Heavy Horses, and Stormwatch — address the natural world from three different angles.

Songs From the Wood is drenched in the atmosphere of the English countryside, where “fairytale creatures, ley lines, naughty equestriennes and the pre-Christian era old gods all came to call," Anderson writes in Silent Singing. The jangling "Jack-in-the-Green," about a raggy character somewhere between a hobbit and the wizard Radagast, is one irresistible highlight.

The majestic Heavy Horses is something of a song cycle about animal life. The serrating opener "...And the Mouse Police Never Sleeps" nails cats, with evocative lines including "Claws that rake a furrow red/ License to mutilate" and "Windy rooftop weathercock/ Warm-blooded night on a cold tile." From there: dogs, moths, weathervanes, the passing of equine generations.

While Stormwatch's compartmentalization as a "folk album" is somewhat suspect — only "Dun Ringill" really fits the mold — it's spiritually connected to Songs From the Wood and Heavy Horses on that conceptual front.

Anderson had addressed climate change before, as on "Skating Away on the Thin Ice of a New Day" on 1974's War Child. ("Predicated on the then-mistaken belief, in popular science circles, that we were headed toward another ice age," Anderson writes in Silent Singing.)

The gloomy Stormwatch takes that theme all the way home; the 1979 album draws its power from the weather and the ocean — as well as paranoia about humanity's bludgeoning impact on it.

As jabs at Exxon and their ilk go, "North Sea Oil" is up there with Neil Young's "Vampire Blues." The heavenward "Orion" is an awestruck gaze at the celestial panorama. And "Dun Ringill" warns "The weather's on the change/ Ice clouds invading and pressure forming."

Nature (The Human Kind)

Anderson may write his songs like a documentarian, but he’s arguably at his most powerful when writes from the human side of the equation.

Their barreling hit “Locomotive Breath,” from Aqualung, is about runaway population growth, through the lens of an “all-time loser” on a brakeless train, “headlong to his death.”

Thirteen tracks into Tull's 1972 odds-and-ends album Living in the Past is their deep cut to end all deep cuts: "Wond'ring Again." A sequel to "Wond'ring Aloud," it's about as angry and voluble as the band ever got.

"The excrement bubbles, this century's slime decays/ And the brainwashing government's lackeys would have us say/ It's under control and we'll soon be on our way/ To a grand year for babies and quiz panel games," goes just one of its dizzying lines.