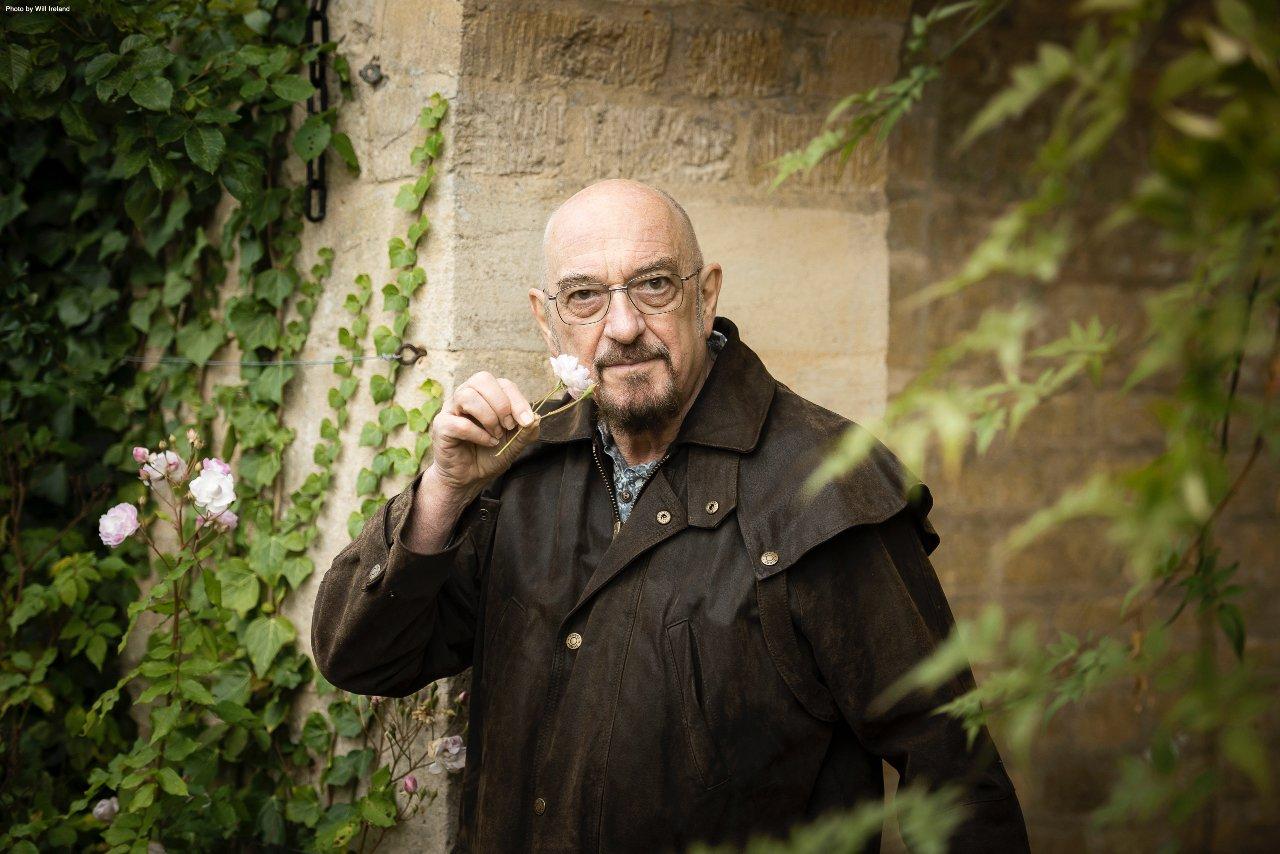

Photo: Will Ireland

interview

Ian Anderson On The Historical Threads Of Fanaticism, Playing Ageless Instruments & Jethro Tull's New Album 'The Zealot Gene'

Ian Anderson never stopped recording and touring, but 'The Zealot Gene' is the first album by his long-running band, Jethro Tull, in 18 years. Here, Anderson opens up about why it took so long — and why he plumbed humanity's capacity for militancy.

Jethro Tull has spent more than 50 years pigeonholed as the classic rock band with the flute — and largely undervalued for their wit, intelligence and heart. But that doesn't stop bandleader Ian Anderson from marveling at the very physicality of his instrument.

"Other than fine-tuning some of the mechanics and the intonation and scale of it, it's the instrument that is 175 years old now," Anderson tells GRAMMY.com, noting that Theobald Boehm perfected the Western concert flute a century before his birth. "I'm a fan of those 'forever' kind of aspects of music-making. They just go on and on and on."

This eternality doesn't just imbue Anderson's instruments of choice — he also plays the acoustic guitar, mandolin and Irish whistle — but informs what he writes and sings about. Sure, he's fascinated by modern technology — he named an album J-Tull Dot Com back in 1999, and any discussion with him is bound to be sprinkled with references to aircraft and artillery.

Read More: Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From This Was To The Zealot Gene

But these days, Anderson wants to know where our political discourse's wild-eyed fervor and immutable rhetoric flows from. And while nobody can pinpoint an ultimate origin for this psychological strain, the GRAMMY-winning progressive-rock giants' latest offering, The Zealot Gene — which arrives Jan. 28 — argues that it's millennia-old at this point. In fact, it's Biblical.

That's the name of the first Jethro Tull album in 18 years — despite several Anderson solo albums since then. (The last one was 2003's The Jethro Tull Christmas Album, partly an album of re-recordings.) Open up Anderson's 2021 lyrics compendium, Silent Singing, and you'll find scriptural citations for each song — "Mrs. Tibbets" comes from Genesis, "Shoshanna Sleeping" from the Song of Solomon, "The Betrayal of Joshua Kynde" from the Gospel of Matthew, and so forth.

Then, you'll notice the Andersonian dimensions of the lyrics — peppered with an English professor's vocabulary. And when you actually listen, you'll hear quintessential Tull — commensurately delicate and thunderous, with opportunities galore to hop on one leg a little.

Despite Anderson being the only remaining original member of the band — fan-favorite guitarist Martin Barre has been out for more than a decade — The Zealot Gene is a treasure box for Tull neophytes and diehards alike. Once an acoustic wafts in on side 2 — nodding toward those on classics like 1971's ***Aqualung ***— it's hard to hear it as anything but a return to form.

GRAMMY.com sat down with Anderson over Zoom to discuss the narrative power of Christianity, the contents of his bookshelf, and how a list of positive and negative words led him to crack open the Bible — and write the first Tull album in ages.

The last Jethro Tull album came out almost 20 years ago — obviously, you've recorded solo albums and toured all over the place since then. But why did you step away from the name for so long?

In 2011, I announced to the band that I was going to embark on a project unspecified for some point in the future. I told Martin Barre and Duane Perry, our drummer, that for the next period of time — whatever that turned out to be — I would be doing some other stuff.

I set out to do the Thick as a Brick 2 album, which is what it turned out to be once I started applying myself to a project, and since it didn't involve two members of the band who had been around for many members, I decided I should release it as a solo album rather than a Jethro Tull album.

And then, subsequently, in 2014, I released Homo Erraticus, which I also released as a solo album. Although, with hindsight, it probably would have been better to have said that was a Jethro Tull album because the guys on the album had been playing with me for many years at that point.

Later on still, when I started working on The Zealot Gene, I decided at that point that I would release it as a Jethro Tull album because the guys in the band had been playing with me as members of Jethro Tull for an average of 15 years.

It seemed like the decent thing to do — to release it as Jethro Tull so they could actually be on a Jethro Tull album, as opposed to just Jethro Tull live concert dates. So, it was written and conceived as a band album, and indeed, it started off to be just that in 2017, when we spent five days in rehearsal and four days recording to do the first seven tracks.

But because of the pressures of touring and other commitments, it didn't get finished. I think I finished four tracks in that year — that I completed vocals and flute and mixed and so on.

Then, it kept getting delayed and delayed because of the very short periods between tours, until the pandemic struck — at which point, I hoped we would get in the studio to finish it off and do the last five songs. But it was not to be, since we were in lockdown and it was unwise for us to be together in a room.

So, I ended up, at the beginning of [2021], deciding I really had to finish the album, and I would just finish the last five tracks at home. And the other guys, some of them sent in their contributions as audio files to be incorporated into the mix.

I presented it to the record company — finished, mixed and mastered — in June. Due to the delays of pressing vinyl, it was never going to be released in [that] calendar year. So, the 28th of January is the official release date due to the seven, eight months of delay and waiting to have the slot at the pressing plant to be able to manufacture.

I'm sure there are Tull fan groups grumbling about the lack of one member or another, but I think this lineup is as valid and powerful as any — especially given that some members have played with you for many years.

Well, the guitarist who is on almost all of The Zealot Gene is Florian Opahle, who left the band at the end of 2019 when he completed his recording studio near Munich, in Germany — a photographic studio to work with his wife, who's a professional photographer.

And so, he decided his touring days were over — although he did come back to do some shows in August and early September of this year, because Joe Parrish, his replacement, was not fully vaccinated at that point — a much younger guy.

So, Florian stepped in to do a few shows to help us out. It was great to have him back, but he is indeed the guitarist on The Zealot Gene — at least on seven of the tracks. Joe Parrish- James contributed a little bit of guitar on one of the remaining five tracks, just so his presence would be there on the album.

But yeah, the guys have been around for a long time. I mean, David Goodier started with me in 2004, John O'Hara in 2005. It goes back a long way working with these same members of the band. So, it's time for recognition that they are well and truly members of Jethro Tull.

After looking up all the scriptures cited in Silent Singing, I think the word "gene" says it all. You're drawing a thread from extremism in ancient history — like that account in Ezekiel of slaughtering the idolators — to what we're seeing today.

Well, it's a fanciful supposition that the human condition embraces something genetic that makes us want — as we say in English vernacular — to get our knickers in a twist.

What I'm really meaning by "zealot" is not a Biblical reference or a reference to Christian zealots, per se. I'm just talking about zealots as being fanatics — people who are fanatical about a certain topic. They could be fanatical about building model railways or attending football matches or following Formula One Grand Prix racing — or fanatical about Michelin-starred restaurants.

But, really, what I'm getting at is "fanatical" in the sense of being very firm and loudly of an opinion — which most people feel, increasingly these days, necessary to express. And freedom of speech, of course, is absolutely vital to us.

But when it starts to hurt other people — when it starts to be divisive socially in the way that populist politicians and national leaders use social media to create division in their society, to set people against each other in order to have a majority, they hope, that will allow them to maintain power — then it gets very ugly.

So, it would be easy to say that "The Zealot Gene," the title track, is modeled on Donald Trump, but that is too easy. It could be one of half a dozen people who immediately spring to mind, who are national leaders of a pretty aggressive and unpleasant sort, who epitomize that idea of being fanatical about their cause and clinging to power at all costs. That idea of fanaticism or powerful emotions runs through the album.

Indeed, it started out as a list of words. I decided I would write each song about a different kind of strong human emotion. And I made a list: some of the good stuff like companionship, loyalty, faithfulness, love — platonic love, brotherly love, spiritual love, erotic love — compassion. And then, I wrote down some bad words: things like "anger," "greed," "jealousy," "retribution."

And I looked at my list of words that I was going to, each one, pick as a subject for a song, and thought, "Oh, these are all words I recall from reading the Bible." So, I looked up all the Biblical references that readily came up in a search that would apply to those descriptions — those words.

I copied and pasted some of those verses from the Bible and put them on a file on my computer that I could use as a ready reference to draw a little comparison from. On really all but one song, I'm taking those ideas and trying to give them relevance to the world we live in today.

I think the only exception, really, is "Mine is the Mountain," which is really set in the Biblical, historical story of Moses going up the mountain to receive the tablets of stone to take down and satisfy his followers — that he was in possession of something powerful and strong that would allow him to maintain his authority and lead his followers to a promised land.

That's something I appreciate as a good narrative and gives Christianity its strength and power. It's a good story. Unlike other religions, it has a continuous narrative. It has a beginning, a fairly short middle and a very powerful ending. But the ending of it brings the promise of something more to come — i.e. series 3 on Netflix.

That's why Christianity has this enormous power as a religion worldwide. It's a narrative. It's a story. And we all love a good story — even if some of it is not entirely credible, historically speaking, or unprovable factually. But I'm a big supporter of Christianity; I just don't choose to call myself a Christian.

My favorite song on the album is "In Brief Visitation," which frames Christ as a "fall guy." It feels charged with love and wonder, but also biting humor — it's quintessential Tull in its outlook. What was going on with that song?

Well, yes, obviously, going back to my notes and the Biblical texts, we are talking about Jesus of Nazareth being, if you like, the "fall guy" for a cause. As a rather radical Jewish prophet as he was, in historical terms, almost certainly. But it's applicable to anybody who perhaps has a brief period of time to try to achieve something, but ends up suffering for the cause and being cast aside.

I think it has lots of applications in the modern world. Sometimes, bad things — because, right now, there is a trial concluding in America where a certain woman is likely to spend the rest of her life in prison if a jury finds that she should so do.

She could be referred to as a "fall guy" — carrying the can for a very dreadful person who is not allowed to face the music because he committed suicide. That's another kind of fall guy — someone who takes the rap because it's easier to pick on somebody who you can actually identify and punish.

That's a bad example in the sense of bad deeds, but there are probably other cases where people who probably do good things still end up being pilloried in some way because they're easy targets.

I think the important thing is, for me, as a writer, that I have a reason for writing something. I can bring it under an overall topic. It can sit under the umbrella of a concept, and the concept is quite simple: it's just to write a bunch of individual songs about extreme emotion.

But I like to tie it together, and that's the fact of using Biblical texts — not as an inspiration, but a little constant reminder of some examples that I can draw upon and flesh out in often contemporary terms.

I appreciate that you've never succumbed to any urge or pressure to streamline or dumb down your ideas for a wider audience. It seems like you've engendered an intelligent following for it.

I don't think it's so important that I do that to the majority of listeners. I think they are perfectly entitled to — and perhaps best advised to — just listen to the music and sing along or tap their foot and enjoy it on a relatively basic level. I don't expect people to go into the detail of what's there.

But I think for those who do want to go into what lies behind something…the general feeling was: yes, we should give the dedicated fans the detail, the information behind the album, how it came to be written, and even include the very first, rough demos that I made and sent out to the members of the band back in early March of 2017.

But I don't think that's necessarily important for the majority of people who will listen to the album — having hopefully paid for it, or downloaded it, or streamed it or whatever. They're not all necessarily interested in what lies behind it, and that's fine by me.

"Jacob's Tales" sounds like it could have been on This Was. "Mine is the Mountain" has a "My God" feeling. The synths throughout the album make me think of Crest of a Knave. Was it a conscious decision to touch on the sounds of Tull's various eras?

Hardly at all. They're just the instruments we play. Essentially, the instruments I play are the instruments I've been playing since I first began professionally.

I play the acoustic guitar; I use it for writing the majority of songs I've written over the years. And I play the flute — another acoustic instrument — and other acoustic instruments which occasionally appear on records. Mandolin, harmonica and the Irish whistle — these things appear on this album in small measure, but they're there.

So, I'm an analog, acoustic kind of guy as a performer. And when you look at the guitars that get played — our bass player plays a Fender Jazz Bass. It's from the 1960s. Our guitar player — well, Florian, on the album — he's playing a Gibson Les Paul, which is another vintage, late-'50s, early-'60s.

And John O'Hara plays the piano and Hammond organ, which, again, are instruments that are part of the history of pop and rock music as well as jazz. And, in the case of piano, of course, it forms a major part of classical music.

So, the instruments we use are fundamentally embedded in the world of contemporary and older forms of music — there's nothing particularly clever about that, technologically. I think where the technology comes in is into the actual recording process, where everything is digitally recorded, mixed and mastered. That's the bit where the technology is contemporary.

I like to embrace the traditions of music-making and incorporate those into modern technological ways of bringing it to the ears of the public. That's my approach to making music, really — it's a mixture of old and new.

And when I get on an aeroplane, very often, I'm sitting on a Boeing 737 — another product of the '60s, still flying today. [There are] several editions further on, but nonetheless, it still looks like the Boeing 737; it smells like the Boeing 737. You know, if you were to pick up the average handgun belonging to a policeman — assuming he would let you do it — you would see inside the magazine some 9mm Parabellum ammunition.

It's been around since the very beginning of the 20th century as the ammunition caliber that is probably, more than any other — in terms of sidearms — been the gold standard. If you can call it that, given that it is something primarily used for killing people. Except, if I have it in my hands, I'm just making holes in a paper target, so that's OK. However, a lot of things seem to go on forever. They seem relatively unchanged in many ways. I rather like that.

The flute I play is an instrument that was designed by Theobald Boehm exactly 100 years before I was born. And essentially, it's still the flute that you would buy if you were a student learning to play the flute, or you were a soloist in the world of classical music… I'm a fan of those "forever" kind of aspects of music-making. They just go on and on and on.

Obviously, we've all flirted with the analog synthesizers of the '70s and the more exotic sampling and sequencing keyboards of the '80s and the '90s. But they are there almost as a substitute for the real thing…for a classical grand piano, or a substitute for a church organ or Hammond organ. It's a matter of convenience, but essentially, not a busting amount has really changed.

So, we're still flying in a Boeing 737 most of the time, in musical terms.

You mentioned the Ghislaine Maxwell trial, and I remember you telling me you'd read George W. Bush's memoir. What else are you reading about these days?

Well, I read a mixture of Nordic noir crime thrillers — just for a bit of light entertainment — and then weightier books on subjects. Comparative religion, spirituality, things to do with fairly deep, philosophical thoughts.

Sometimes, they're more contemporary, but nonetheless, somewhat philosophical by contemporary popular writers who will go into topics of everything from ecology, to climate change, through to the societal changes happening these days and where we might be headed in the future.

Again, it's the contrast that appeals to me, I suppose. If I only read one kind of thing all the time, it would be a little dull.

It seems like you're always working on Tull-related books or putting out boxed sets for various anniversaries. How would you break down an average day in your life, from a professional standpoint?

I usually get up at six in the morning — sometimes a little earlier. I come down, do a couple of hours' work in the office. And then, I usually have my morning round of promo interviews to do, if I'm working with a new project, like the album — [which] is, for me, quite demanding from a promo point of view.

So, I've got a few hours of press and promo to do in the morning, as per the European side of things, and then I've got press and promo to do in North America and other territories on very different time zones. That happens in the afternoon. I'm probably at my office desk much of the day, but I'm not actually rehearsing, practicing and playing the flute.

I'm about to start a new project on Jan. 1 of [2022]. In a couple of weeks, I will begin the next album. The great thing is that I have no idea what it's going to be about.

At nine o'clock on the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse, who — should she decide to visit — hopefully, by 10 o'clock, I'll have the beginnings of some kind of flicker of an idea. And by lunchtime, I might have a few ideas. And over the period of the next three or four weeks, I might think I'd completed the first draft of something — musically and lyrically — for a new album.

That's partly wishful thinking, and partly putting myself on the spot. I like the idea of challenging myself to do what I say I'm going to do, and usually managing to do it, as I have done since 2011 with Thick as a Brick 2, the Homo Erraticus album, the String Quartets album, the Zealot Gene album. I've set out to do those things at a certain point, and I like to think I get results.

But sooner or later, I will meet the dreaded writer's block and probably burst into tears or have to be carried into my bed.

So there's nothing to reveal about the next album, because you haven't even opened your mind to the ether yet.

Well, no. I think the thing is that if I started dwelling on that now, I would start to have some ideas, and it's too early. I just want to wait for that magic moment to present itself.

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Assunta Opahle

feature

Ian Anderson Of Jethro Tull’s Themes & Inspirations, From 'RökFlöte' Backward

Jethro Tull's new album 'RökFlöte' is deeply influenced by old Norse paganism. And as per Ian Anderson's bank of lyrical concepts, it only scratches the surface.

Ian Anderson was finishing up an interview about the first Jethro Tull album in almost two decades, 2022’s The Zealot Gene, when he offered GRAMMY.com some tantalizing news: the next one would arrive sooner rather than later.

"At 9 o'clock on the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse," Anderson said two weeks before the end of 2021. "Should she decide to visit — hopefully, by 10 o'clock, I'll have the beginnings of some kind of flicker of an idea."

Where might Anderson, a voracious reader with a sweeping purview and a learned, gentlemanly air, go from there?

Fast forward to today, and we have the result: RökFlöte, which arrived April 21 and is based on "the characters and roles of some of the princip[al] gods of the old Norse paganism."

The GRAMMY-winning prog-rock heroes’ catalog has always been flecked with similar mythology, especially on 1977's fantastical, bucolic Songs From the Wood. But never had Anderson dedicated an entire album to this specific system of concepts.

RökFlöte’s opener, "Voluspo," is titled after the most famous poem in the Poetic Edda, which dates back centuries. Lead single "Ginnungagap" refers to the bottomless abyss that encompassed all things prior to the creation of the cosmos. "Ithavoll" is the meeting place of the gods.

This sheer depth of reference is not new for Anderson and company. A band less cited for their musical and philosophical depth than mined for cheap codpiece and Anchorman jokes, Jethro Tull contain multitudes just beneath the surface.

Take a stroll through the band's discography, and you'll find Anderson doesn't linger on one topic for long — and often addresses many concepts within the same album, or even song. Even Tull's most straightforward hits often contain richer meaning than what immediately meets the ear.

To celebrate the release of RökFlöte, here's a by-no-means-comprehensive breakdown of the poles Anderson and crew have tended to touch on throughout the band' almost 60-year career.

Love (With Some Caveats)

"I am a descriptive writer," Anderson wrote in the preface to his career-spanning compendium of lyrics, Silent Singing. "Not so often a storyteller, and almost never a heart-on-sleeve love-rat. Social documentary that you can hum along to."

True, this applies to the lion's share of his songs. But there are a couple of major exceptions — perhaps ones that prove the rule.

Take "Wond'ring Aloud," his gorgeous acoustic ballad on 1971's Aqualung that clocks in at less than two minutes. If there's any kind of social commentary or obscure meaning in "Wond'ring Aloud," it's difficult to tease out. Rather, the tune unfurls a quiet, domestic tableau of romantic bliss:

"Last night sipped the sunset/ My hand in her hair," he sings. "We are our own saviors as we start/ Both our hearts beating life into each other." The aroma of breakfast wafts through the kitchen; he considers their years ahead. Then, the unforgettable closing line: "And it's only the giving that makes you what you are."

Flash forward to "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All," another gobsmacking acoustic-with-strings centerpiece, from 1975's Minstrel in the Gallery.

Online chatter seems to suggest that the image of "one white duck on your wall" refers to a domestic split. Whatever the case, the darkly romantic song is suggestive of packing and leaving: "There's a haze on the skyline to wish me on my way/ There's a note on the telephone, some roses on a tray." From there, the song unfurls into a litany of images, commensurately puzzling and evocative — and full of arcane British-isms.

Like every other arena of life represented in Jethro Tull songs, romance comes with bottomless shades and nuances — and Anderson's seemingly attuned to the full spectrum.

Religion (As A Nonbeliever)

Jethro Tull classics that address faith, like Aqualung's "My God," "Hymn 43" and "Wind Up," excoriate religious corruption and dogma — to the degree that Anderson comes across as defensive of God.

"It's about turning God into a vehicle for personal power and the glitz and paraphernalia that sometimes surrounds religion," Anderson wrote of "My God" in 2019's oral history of the band, The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "It's actually quite pro-God in asking: 'People what have you done/ Locked him in his golden cage?'"

In "Wind Up," he rails: "I don't believe you/ You have the whole damn thing all wrong/ He's not the kind you have to wind up on Sundays." But it's crucial to stress that Anderson is decidedly not a man of faith.

Read More: Jethro Tull's Aqualung At 50: Ian Anderson On How Whimsy, Inquiry & Religious Skepticism Forged The Progressive Rock Classic

"I've learned to describe myself as somewhere between a pantheist and a deist," he wrote. "I'm not a Christian, but I like to do things for the church. I've always believed there are certain aspects of our society that, while anachronistic, are still worth preserving."

In an Olde English font in the Aqualung sleeve, Anderson printed a facsimile of Genesis 1:1: "In the beginning Man created God; and in the image of Man created He him."

Of the religious commentary scattered throughout Tull's discography, none seem to summarize Anderson's views like the above.

Nature (The Non-Human Kind)

Jethro Tull's so-called "folk trilogy" in the late 1970s — Songs From the Wood, Heavy Horses, and Stormwatch — address the natural world from three different angles.

Songs From the Wood is drenched in the atmosphere of the English countryside, where “fairytale creatures, ley lines, naughty equestriennes and the pre-Christian era old gods all came to call," Anderson writes in Silent Singing. The jangling "Jack-in-the-Green," about a raggy character somewhere between a hobbit and the wizard Radagast, is one irresistible highlight.

The majestic Heavy Horses is something of a song cycle about animal life. The serrating opener "...And the Mouse Police Never Sleeps" nails cats, with evocative lines including "Claws that rake a furrow red/ License to mutilate" and "Windy rooftop weathercock/ Warm-blooded night on a cold tile." From there: dogs, moths, weathervanes, the passing of equine generations.

While Stormwatch's compartmentalization as a "folk album" is somewhat suspect — only "Dun Ringill" really fits the mold — it's spiritually connected to Songs From the Wood and Heavy Horses on that conceptual front.

Anderson had addressed climate change before, as on "Skating Away on the Thin Ice of a New Day" on 1974's War Child. ("Predicated on the then-mistaken belief, in popular science circles, that we were headed toward another ice age," Anderson writes in Silent Singing.)

The gloomy Stormwatch takes that theme all the way home; the 1979 album draws its power from the weather and the ocean — as well as paranoia about humanity's bludgeoning impact on it.

As jabs at Exxon and their ilk go, "North Sea Oil" is up there with Neil Young's "Vampire Blues." The heavenward "Orion" is an awestruck gaze at the celestial panorama. And "Dun Ringill" warns "The weather's on the change/ Ice clouds invading and pressure forming."

Nature (The Human Kind)

Anderson may write his songs like a documentarian, but he’s arguably at his most powerful when writes from the human side of the equation.

Their barreling hit “Locomotive Breath,” from Aqualung, is about runaway population growth, through the lens of an “all-time loser” on a brakeless train, “headlong to his death.”

Thirteen tracks into Tull's 1972 odds-and-ends album Living in the Past is their deep cut to end all deep cuts: "Wond'ring Again." A sequel to "Wond'ring Aloud," it's about as angry and voluble as the band ever got.

"The excrement bubbles, this century's slime decays/ And the brainwashing government's lackeys would have us say/ It's under control and we'll soon be on our way/ To a grand year for babies and quiz panel games," goes just one of its dizzying lines.

But Anderson’s perspective isn’t always from a 50,000-foot view. In other tunes, he cuts to the chase regarding what makes humanity tick.

Read More: Ian Anderson On The Historical Threads Of Fanaticism, Playing Ageless Instruments & Jethro Tull's New Album The Zealot Gene

A goof on what Anderson perceived as bloated concept albums of the day, the narrative of 1972's one-song album Thick as a Brick flows in all directions. Yet the opening salvo, titled "Ready Don't Mind" on later editions, is especially incisive in its needling of small-minded biases.

"I may make you feel, but I can't make you think," Anderson declares amid the backdrop of "the sandcastle virtues… all swept away/In the tidal destruction, the moral melee."

On "Aqualung," Tull's classic portrait of a seedy, streetbound derelict, Anderson zooms in on how the straights perceive this loathsome character.

"[It's] more in terms of our reaction to the homeless," Anderson explained to GRAMMY.com in 2021. "I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel — compassion, fear, embarrassment. It's a very mixed and contradictory set of emotions."

Anderson’s reflections on human nature and the social order are not always that heavy; 1976's underrated Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! explores "the cyclical nature of fashion, music and youth culture" through the lens of a hapless, aging protagonist, trapped in the mire of his youthful interests.

The American rocker in "Said She Was a Dancer" from 1987's Crest of a Knave is similarly over-the-hill, as he flirts with a disinterested Muscovite. What a clash between "Eastern steel and Western gold": "You've seen me in your magazines, or maybe on state television," he complains. "I'm your Pepsi-Cola, but you won't take me out the can."

From here, you can open Silent Singing and head in any direction — horny Tull ("Kissing Willie," "Roll Yer Own"), tech-curious Tull ("Dot Com"), and even odes to household objects ("Wicked Windows," about eyeglasses.)

If you're already a Tull fan, chances are a dozen more examples of these umbrella concepts have already popped into your head. If you're a newbie, you've stumbled on one of the most eclectic, intelligent, criminally misunderstood rock bands of all time. Cheerio!

Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From This Was To The Zealot Gene

Photo: Rachel Kupfer

list

A Guide To Modern Funk For The Dance Floor: L'Imperatrice, Shiro Schwarz, Franc Moody, Say She She & Moniquea

James Brown changed the sound of popular music when he found the power of the one and unleashed the funk with "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." Today, funk lives on in many forms, including these exciting bands from across the world.

It's rare that a genre can be traced back to a single artist or group, but for funk, that was James Brown. The Godfather of Soul coined the phrase and style of playing known as "on the one," where the first downbeat is emphasized, instead of the typical second and fourth beats in pop, soul and other styles. As David Cheal eloquently explains, playing on the one "left space for phrases and riffs, often syncopated around the beat, creating an intricate, interlocking grid which could go on and on." You know a funky bassline when you hear it; its fat chords beg your body to get up and groove.

Brown's 1965 classic, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," became one of the first funk hits, and has been endlessly sampled and covered over the years, along with his other groovy tracks. Of course, many other funk acts followed in the '60s, and the genre thrived in the '70s and '80s as the disco craze came and went, and the originators of hip-hop and house music created new music from funk and disco's strong, flexible bones built for dancing.

Legendary funk bassist Bootsy Collins learned the power of the one from playing in Brown's band, and brought it to George Clinton, who created P-funk, an expansive, Afrofuturistic, psychedelic exploration of funk with his various bands and projects, including Parliament-Funkadelic. Both Collins and Clinton remain active and funkin', and have offered their timeless grooves to collabs with younger artists, including Kali Uchis, Silk Sonic, and Omar Apollo; and Kendrick Lamar, Flying Lotus, and Thundercat, respectively.

In the 1980s, electro-funk was born when artists like Afrika Bambaataa, Man Parrish, and Egyptian Lover began making futuristic beats with the Roland TR-808 drum machine — often with robotic vocals distorted through a talk box. A key distinguishing factor of electro-funk is a de-emphasis on vocals, with more phrases than choruses and verses. The sound influenced contemporaneous hip-hop, funk and electronica, along with acts around the globe, while current acts like Chromeo, DJ Stingray, and even Egyptian Lover himself keep electro-funk alive and well.

Today, funk lives in many places, with its heavy bass and syncopated grooves finding way into many nooks and crannies of music. There's nu-disco and boogie funk, nodding back to disco bands with soaring vocals and dance floor-designed instrumentation. G-funk continues to influence Los Angeles hip-hop, with innovative artists like Dam-Funk and Channel Tres bringing the funk and G-funk, into electro territory. Funk and disco-centered '70s revival is definitely having a moment, with acts like Ghost Funk Orchestra and Parcels, while its sparkly sprinklings can be heard in pop from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, and, in full "Soul Train" character, Silk Sonic. There are also acts making dreamy, atmospheric music with a solid dose of funk, such as Khruangbin’s global sonic collage.

There are many bands that play heavily with funk, creating lush grooves designed to get you moving. Read on for a taste of five current modern funk and nu-disco artists making band-led uptempo funk built for the dance floor. Be sure to press play on the Spotify playlist above, and check out GRAMMY.com's playlist on Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

Say She She

Aptly self-described as "discodelic soul," Brooklyn-based seven-piece Say She She make dreamy, operatic funk, led by singer-songwriters Nya Gazelle Brown, Piya Malik and Sabrina Mileo Cunningham. Their '70s girl group-inspired vocal harmonies echo, sooth and enchant as they cover poignant topics with feminist flair.

While they’ve been active in the New York scene for a few years, they’ve gained wider acclaim for the irresistible music they began releasing this year, including their debut album, Prism. Their 2022 debut single "Forget Me Not" is an ode to ground-breaking New York art collective Guerilla Girls, and "Norma" is their protest anthem in response to the news that Roe vs. Wade could be (and was) overturned. The band name is a nod to funk legend Nile Rodgers, from the "Le freak, c'est chi" exclamation in Chic's legendary tune "Le Freak."

Moniquea

Moniquea's unique voice oozes confidence, yet invites you in to dance with her to the super funky boogie rhythms. The Pasadena, California artist was raised on funk music; her mom was in a cover band that would play classics like Aretha Franklin’s "Get It Right" and Gladys Knight’s "Love Overboard." Moniquea released her first boogie funk track at 20 and, in 2011, met local producer XL Middelton — a bonafide purveyor of funk. She's been a star artist on his MoFunk Records ever since, and they've collabed on countless tracks, channeling West Coast energy with a heavy dose of G-funk, sunny lyrics and upbeat, roller disco-ready rhythms.

Her latest release is an upbeat nod to classic West Coast funk, produced by Middleton, and follows her February 2022 groovy, collab-filled album, On Repeat.

Shiro Schwarz

Shiro Schwarz is a Mexico City-based duo, consisting of Pammela Rojas and Rafael Marfil, who helped establish a modern funk scene in the richly creative Mexican metropolis. On "Electrify" — originally released in 2016 on Fat Beats Records and reissued in 2021 by MoFunk — Shiro Schwarz's vocals playfully contrast each other, floating over an insistent, upbeat bassline and an '80s throwback electro-funk rhythm with synth flourishes.

Their music manages to be both nostalgic and futuristic — and impossible to sit still to. 2021 single "Be Kind" is sweet, mellow and groovy, perfect chic lounge funk. Shiro Schwarz’s latest track, the joyfully nostalgic "Hey DJ," is a collab with funkstress Saucy Lady and U-Key.

L'Impératrice

L'Impératrice (the empress in French) are a six-piece Parisian group serving an infectiously joyful blend of French pop, nu-disco, funk and psychedelia. Flore Benguigui's vocals are light and dreamy, yet commanding of your attention, while lyrics have a feminist touch.

During their energetic live sets, L'Impératrice members Charles de Boisseguin and Hagni Gwon (keys), David Gaugué (bass), Achille Trocellier (guitar), and Tom Daveau (drums) deliver extended instrumental jam sessions to expand and connect their music. Gaugué emphasizes the thick funky bass, and Benguigui jumps around the stage while sounding like an angel. L’Impératrice’s latest album, 2021’s Tako Tsubo, is a sunny, playful French disco journey.

Franc Moody

Franc Moody's bio fittingly describes their music as "a soul funk and cosmic disco sound." The London outfit was birthed by friends Ned Franc and Jon Moody in the early 2010s, when they were living together and throwing parties in North London's warehouse scene. In 2017, the group grew to six members, including singer and multi-instrumentalist Amber-Simone.

Their music feels at home with other electro-pop bands like fellow Londoners Jungle and Aussie act Parcels. While much of it is upbeat and euphoric, Franc Moody also dips into the more chilled, dreamy realm, such as the vibey, sultry title track from their recently released Into the Ether.

Photo: Steven Sebring

interview

Living Legends: Billy Idol On Survival, Revival & Breaking Out Of The Cage

"One foot in the past and one foot into the future," Billy Idol says, describing his decade-spanning career in rock. "We’ve got the best of all possible worlds because that has been the modus operandi of Billy Idol."

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com spoke with Billy Idol about his latest EP, Cage, and continuing to rock through decades of changing tastes.

Billy Idol is a true rock 'n' roll survivor who has persevered through cultural shifts and personal struggles. While some may think of Idol solely for "Rebel Yell" and "White Wedding," the singer's musical influences span genres and many of his tunes are less turbo-charged than his '80s hits would belie.

Idol first made a splash in the latter half of the '70s with the British punk band Generation X. In the '80s, he went on to a solo career combining rock, pop, and punk into a distinct sound that transformed him and his musical partner, guitarist Steve Stevens, into icons. They have racked up multiple GRAMMY nominations, in addition to one gold, one double platinum, and four platinum albums thanks to hits like "Cradle Of Love," "Flesh For Fantasy," and "Eyes Without A Face."

But, unlike many legacy artists, Idol is anything but a relic. Billy continues to produce vital Idol music by collaborating with producers and songwriters — including Miley Cyrus — who share his forward-thinking vision. He will play a five-show Vegas residency in November, and filmmaker Jonas Akerlund is working on a documentary about Idol’s life.

His latest release is Cage, the second in a trilogy of annual four-song EPs. The title track is a classic Billy Idol banger expressing the desire to free himself from personal constraints and live a better life. Other tracks on Cage incorporate metallic riffing and funky R&B grooves.

Idol continues to reckon with his demons — they both grappled with addiction during the '80s — and the singer is open about those struggles on the record and the page. (Idol's 2014 memoir Dancing With Myself, details a 1990 motorcycle accident that nearly claimed a leg, and how becoming a father steered him to reject hard drugs. "Bitter Taste," from his last EP, The Roadside, reflects on surviving the accident.)

Although Idol and Stevens split in the late '80s — the skilled guitarist fronted Steve Stevens & The Atomic Playboys, and collaborated with Michael Jackson, Rick Ocasek, Vince Neil, and Harold Faltermeyer (on the GRAMMY-winning "Top Gun Anthem") — their common history and shared musical bond has been undeniable. The duo reunited in 2001 for an episode of "VH1 Storytellers" and have been back in the saddle for two decades. Their union remains one of the strongest collaborations in rock 'n roll history.

While there is recognizable personnel and a distinguishable sound throughout a lot of his work, Billy Idol has always pushed himself to try different things. Idol discusses his musical journey, his desire to constantly move forward, and the strong connection that he shares with Stevens.

Steve has said that you like to mix up a variety of styles, yet everyone assumes you're the "Rebel Yell"/"White Wedding" guy. But if they really listen to your catalog, it's vastly different.

Yeah, that's right. With someone like Steve Stevens, and then back in the day Keith Forsey producing... [Before that] Generation X actually did move around inside punk rock. We didn't stay doing just the Ramones two-minute music. We actually did a seven-minute song. [Laughs]. We did always mix things up.

Then when I got into my solo career, that was the fun of it. With someone like Steve, I knew what he could do. I could see whatever we needed to do, we could nail it. The world was my oyster musically.

"Cage" is a classic-sounding Billy Idol rocker, then "Running From The Ghost" is almost metal, like what the Devil's Playground album was like back in the mid-2000s. "Miss Nobody" comes out of nowhere with this pop/R&B flavor. What inspired that?

We really hadn't done anything like that since something like "Flesh For Fantasy" [which] had a bit of an R&B thing about it. Back in the early days of Billy Idol, "Hot In The City" and "Mony Mony" had girls [singing] on the backgrounds.

We always had a bit of R&B really, so it was actually fun to revisit that. We just hadn't done anything really quite like that for a long time. That was one of the reasons to work with someone like Sam Hollander [for the song "Rita Hayworth"] on The Roadside. We knew we could go [with him] into an R&B world, and he's a great songwriter and producer. That's the fun of music really, trying out these things and seeing if you can make them stick.

I listen to new music by veteran artists and debate that with some people. I'm sure you have those fans that want their nostalgia, and then there are some people who will embrace the newer stuff. Do you find it’s a challenge to reach people with new songs?

Obviously, what we're looking for is, how do we somehow have one foot in the past and one foot into the future? We’ve got the best of all possible worlds because that has been the modus operandi of Billy Idol.

You want to do things that are true to you, and you don't just want to try and do things that you're seeing there in the charts today. I think that we're achieving it with things like "Running From The Ghost" and "Cage" on this new EP. I think we’re managing to do both in a way.

**Obviously, "Running From The Ghost" is about addiction, all the stuff that you went through, and in "Cage" you’re talking about freeing yourself from a lot of personal shackles. Was there any one moment in your life that made you really thought I have to not let this weigh me down anymore?**

I mean, things like the motorcycle accident I had, that was a bit of a wake up call way back. It was 32 years ago. But there were things like that, years ago, that gradually made me think about what I was doing with my life. I didn't want to ruin it, really. I didn't want to throw it away, and it made [me] be less cavalier.

I had to say to myself, about the drugs and stuff, that I've been there and I've done it. There’s no point in carrying on doing it. You couldn't get any higher. You didn't want to throw your life away casually, and I was close to doing that. It took me a bit of time, but then gradually I was able to get control of myself to a certain extent [with] drugs and everything. And I think Steve's done the same thing. We're on a similar path really, which has been great because we're in the same boat in terms of lyrics and stuff.

So a lot of things like that were wake up calls. Even having grandchildren and just watching my daughter enlarging her family and everything; it just makes you really positive about things and want to show a positive side to how you're feeling, about where you're going. We've lived with the demons so long, we've found a way to live with them. We found a way to be at peace with our demons, in a way. Maybe not completely, but certainly to where we’re enjoying what we do and excited about it.

[When writing] "Running From The Ghost" it was easy to go, what was the ghost for us? At one point, we were very drug addicted in the '80s. And Steve in particular is super sober [now]. I mean, I still vape pot and stuff. I don’t know how he’s doing it, but it’s incredible. All I want to be able to do is have a couple of glasses of wine at a restaurant or something. I can do that now.

I think working with people that are super talented, you just feel confident. That is a big reason why you open up and express yourself more because you feel comfortable with what's around you.

Did you watch Danny Boyle's recent Sex Pistols mini-series?

I did, yes.

You had a couple of cameos; well, an actor who portrayed you did. How did you react to it? How accurate do you think it was in portraying that particular time period?

I love Jonesy’s book, I thought his book was incredible. It's probably one of the best bio books really. It was incredible and so open. I was looking forward to that a lot.

It was as if [the show] kind of stayed with Steve [Jones’ memoir] about halfway through, and then departed from it. [John] Lydon, for instance, was never someone I ever saw acting out; he's more like that today. I never saw him do something like jump up in the room and run around going crazy. The only time I saw him ever do that was when they signed the recording deal with Virgin in front of Buckingham Palace. Whereas Sid Vicious was always acting out; he was always doing something in a horrible way or shouting at someone. I don't remember John being like that. I remember him being much more introverted.

But then I watched interviews with some of the actors about coming to grips with the parts they were playing. And they were saying, we knew punk rock happened but just didn't know any of the details. So I thought well, there you go. If ["Pistol" is] informing a lot of people who wouldn't know anything about punk rock, maybe that's what's good about it.

Maybe down the road John Lydon will get the chance to do John's version of the Pistols story. Maybe someone will go a lot deeper into it and it won't be so surface. But maybe you needed this just to get people back in the flow.

We had punk and metal over here in the States, but it feels like England it was legitimately more dangerous. British society was much more rigid.

It never went [as] mega in America. It went big in England. It exploded when the Pistols did that interview with [TV host Bill] Grundy, that lorry truck driver put his boot through his own TV, and all the national papers had "the filth and the fury" [headlines].

We went from being unknown to being known overnight. We waited a year, Generation X. We even told them [record labels] no for nine months to a year. Every record company wanted their own punk rock group. So it went really mega in England, and it affected the whole country – the style, the fashions, everything. I mean, the Ramones were massive in England. Devo had a No. 1 song [in England] with "Satisfaction" in '77. Actually, Devo was as big as or bigger than the Pistols.

You were ahead of the pop-punk thing that happened in the late '90s, and a lot of it became tongue-in-cheek by then. It didn't have the same sense of rebelliousness as the original movement. It was more pop.

It had become a style. There was a famous book in England called Revolt Into Style — and that's what had happened, a revolt that turned into style which then they were able to duplicate in their own way. Even recently, Billie Joe [Armstrong] did his own version of "Gimme Some Truth," the Lennon song we covered way back in 1977.

When we initially were making [punk] music, it hadn't become accepted yet. It was still dangerous and turned into a style that people were used to. We were still breaking barriers.

You have a band called Generation Sex with Steve Jones and Paul Cook. I assume you all have an easier time playing Pistols and Gen X songs together now and not worrying about getting spit on like back in the '70s?

Yeah, definitely. When I got to America I told the group I was putting it together, "No one spits at the audience."

We had five years of being spat on [in the UK], and it was revolting. And they spat at you if they liked you. If they didn't like it they smashed your gear up. One night, I remember I saw blood on my T-shirt, and I think Joe Strummer got meningitis when spit went in his mouth.

You had to go through a lot to become successful, it wasn't like you just kind of got up there and did a couple of gigs. I don't think some young rock bands really get that today.

With punk going so mega in England, we definitely got a leg up. We still had a lot of work to get where we got to, and rightly so because you find out that you need to do that. A lot of groups in the old days would be together three to five years before they ever made a record, and that time is really important. In a way, what was great about punk rock for me was it was very much a learning period. I really learned a lot [about] recording music and being in a group and even writing songs.

Then when I came to America, it was a flow, really. I also really started to know what I wanted Billy Idol to be. It took me a little bit, but I kind of knew what I wanted Billy Idol to be. And even that took a while to let it marinate.

You and Miley Cyrus have developed a good working relationship in the last several years. How do you think her fans have responded to you, and your fans have responded to her?

I think they're into it. It's more the record company that she had didn't really get "Night Crawling"— it was one of the best songs on Plastic Hearts, and I don't think they understood that. They wanted to go with Dua Lipa, they wanted to go with the modern, young acts, and I don't think they realized that that song was resonating with her fans. Which is a shame really because, with Andrew Watt producing, it's a hit song.

But at the same time, I enjoyed doing it. It came out really good and it's very Billy Idol. In fact, I think it’s more Billy Idol than Miley Cyrus. I think it shows you where Andrew Watt was. He was excited about doing a Billy Idol track. She's fun to work with. She’s a really great person and she works at her singing — I watched her rehearsing for the Super Bowl performance she gave. She rehearsed all Saturday morning, all Saturday afternoon, and Sunday morning and it was that afternoon. I have to admire her fortitude. She really cares.

I remember when you went on "Viva La Bam" back in 2005 and decided to give Bam Margera’s Lamborghini a new sunroof by taking a power saw to it. Did he own that car? Was that a rental?

I think it was his car.

Did he get over it later on?

He loved it. [Laughs] He’s got a wacky sense of humor. He’s fantastic, actually. I’m really sorry to see what he's been going through just lately. He's going through a lot, and I wish him the best. He's a fantastic person, and it's a shame that he's struggling so much with his addictions. I know what it's like. It's not easy.

Musically, what is the synergy like with you guys during the past 10 years, doing Kings and Queens of the Underground and this new stuff? What is your working relationship like now in this more sober, older, mature version of you two as opposed to what it was like back in the '80s?

In lots of ways it’s not so different because we always wrote the songs together, we always talked about what we're going to do together. It was just that we were getting high at the same time.We're just not getting [that way now] but we're doing all the same things.

We're still talking about things, still [planning] things:What are we going to do next? How are we going to find new people to work with? We want to find new producers. Let's be a little bit more timely about putting stuff out.That part of our relationship is the same, you know what I mean? That never got affected. We just happened to be overloading in the '80s.

The relationship’s… matured and it's carrying on being fruitful, and I think that's pretty amazing. Really, most people don't get to this place. Usually, they hate each other by now. [Laughs] We also give each other space. We're not stopping each other doing things outside of what we’re working on together. All of that enables us to carry on working together. I love and admire him. I respect him. He's been fantastic. I mean, just standing there on stage with him is always a treat. And he’s got an immensely great sense of humor. I think that's another reason why we can hang together after all this time because we've got the sense of humor to enable us to go forward.

There's a lot of fan reaction videos online, and I noticed a lot of younger women like "Rebel Yell" because, unlike a lot of other '80s alpha male rock tunes, you're talking about satisfying your lover.

It was about my girlfriend at the time, Perri Lister. It was about how great I thought she was, how much I was in love with her, and how great women are, how powerful they are.

It was a bit of a feminist anthem in a weird way. It was all about how relationships can free you and add a lot to your life. It was a cry of love, nothing to do with the Civil War or anything like that. Perri was a big part of my life, a big part of being Billy Idol. I wanted to write about it. I'm glad that's the effect.

Is there something you hope people get out of the songs you've been doing over the last 10 years? Do you find yourself putting out a message that keeps repeating?

Well, I suppose, if anything, is that you can come to terms with your life, you can keep a hold of it. You can work your dreams into reality in a way and, look, a million years later, still be enjoying it.

The only reason I'm singing about getting out of the cage is because I kicked out of the cage years ago. I joined Generation X when I said to my parents, "I'm leaving university, and I'm joining a punk rock group." And they didn't even know what a punk rock group was. Years ago, I’d write things for myself that put me on this path, so that maybe in 2022 I could sing something like "Cage" and be owning this territory and really having a good time. This is the life I wanted.

The original UK punk movement challenged societal norms. Despite all the craziness going on throughout the world, it seems like a lot of modern rock bands are afraid to do what you guys were doing. Do you think we'll see a shift in that?

Yeah. Art usually reacts to things, so I would think eventually there will be a massive reaction to the pop music that’s taken over — the middle of the road music, and then this kind of right wing politics. There will be a massive reaction if there's not already one. I don’t know where it will come from exactly. You never know who's gonna do [it].