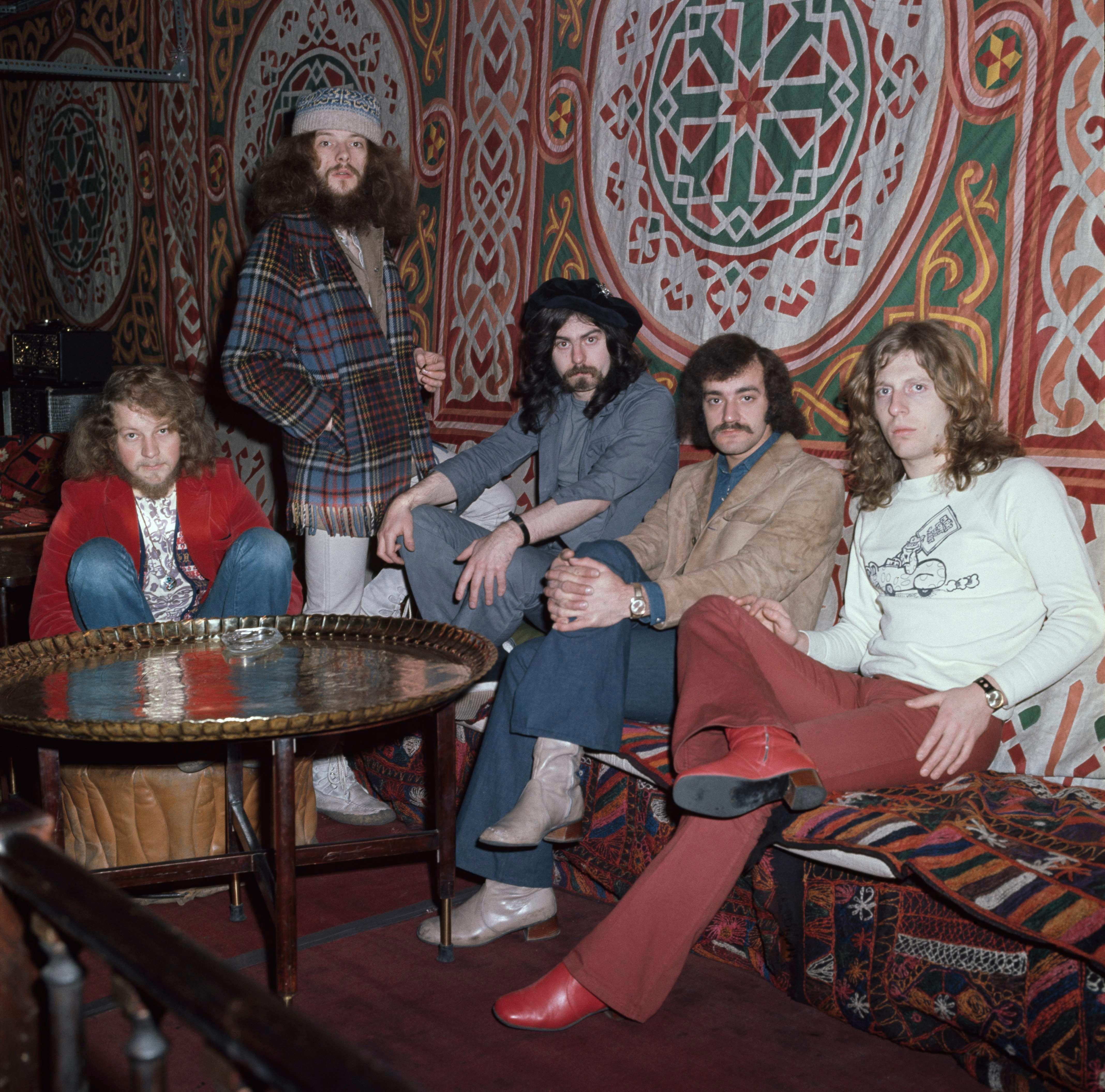

Photo: Michael Putland/Getty Images

Jethro Tull in 1971

news

Jethro Tull's 'Aqualung' At 50: Ian Anderson On How Whimsy, Inquiry & Religious Skepticism Forged The Progressive Rock Classic

Ian Anderson wasn't sure if Jethro Tull's fourth album, 'Aqualung,' could beat the last three. But the 1971 album turned out to be their masterpiece, consolidating Anderson's feelings about homelessness, love, God and an overpopulated Earth

By now, Jethro Tull's "Aqualung" has been lampooned by everyone from Ron Burgundy to Tony Soprano, but the song's import goes many layers deeper than throwaway jokes. It arguably could save the world.

Sure, everybody remembers that thunderclap six-note riff and leader Ian Anderson's snarling portrait of a disreputable street dweller, "eyeing little girls with bad intent." What happens next in the song is less discussed.

Over tranquil acoustic strums, Anderson sings of the itinerant character not with disgust but with almost Christlike compassion. He paints a detailed portrait of his daily routine. He takes pity on his loneliness. Most tenderly, he addresses him as "my friend."

Fifty years after Aqualung was released on March 19, 1971, it's safe to say this attitude hasn't been evergreen. In an era of quick demonization, most wouldn't try to understand Aqualung's plight or even give him the time of day.

"I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel—compassion, fear, embarrassment," Anderson tells GRAMMY.com of the title track. "It's a very mixed and contradictory set of emotions, but I think part of the way of dealing with these things is to try to understand why you feel those things."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//61PMgwdGOQg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

This spirit of open, honest dialogue imbues the entire album, which Anderson wrote and he, guitarist Martin Barre, bassist Jeffrey Hammond, keyboardist John Evan and drummer Clive Bunker performed. On "My God," "Hymn 43" and "Wind-Up," Anderson analyzed organized religion and its connection to God—or lack thereof.

"I don't believe you/ You've got the whole damn thing all wrong/ He's not the kind you have to wind up on Sundays," he proclaimed in "Wind-Up." Some foreign governments banned the album or bleeped out offending lyrics; Bible Belters burned it.

Is this how we should deal with offending art or those we find repugnant? To Anderson, the real solution begins with turning off social media and having authentic conversations. (Yes, even with those we can't stand.)

GRAMMY.com gave Ian Anderson a ring about the writing and recording of Aqualung, his complicated relationship with religion and why "ranting and raving on Twitter... does no good for anybody."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//FpH_WkjC_Yk' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Where was Jethro Tull at the dawn of the decade, between 1970's Benefit and Aqualung?

On tour in the U.S.A., a great deal of the time. The songs for Aqualung began—not all of them, but many of them—in Holiday Inns and similar premises through the Midwest of America. The song "Aqualung," I remember writing in a hotel. We had moved on to having separate rooms by then, so it gave me some privacy to write songs and I always had a guitar with me.

So, I remember calling Martin Barre and saying, "Hey, come up to my room. I want to run through a new song with you." He came to my room with his electric guitar—no amplifier, so I couldn't really hear what he was playing—and I showed him the essential riffs and chords through "Aqualung." He didn't imagine, as I did, how it would sound if it was plugged into an amplifier turned up to [chuckles] number 11.

I said, "Trust me, trust me. Play this riff and it's going to be a big thing." I had an acoustic guitar and he wasn't plugged in, so you had to have faith and try to use your imagination. But as a record producer, that's what I was supposed to have, so I figured I would be able to demonstrate the drama and the contrast in the song when it came to playing it on stage.

I think "My God" was another early one that was written—and, in fact, performed—during the summer of 1970. It had slightly different lyrics, but it was one of the first songs that was complete for the Aqualung album. Many of the rest followed on toward the end of the year, and some of them were written pretty much in the studio or around the time of the recording sessions. So, it was varied.

"Mother Goose," I remember that. That was pretty early on. That was in the summer of 1970 as well. So, it spanned a period of time, really, from the summer of '70 through to the end of the year, writing the music and recording. It was an experience, being an album that suffered a little bit from production problems in the then-brand-new studio that Island Records had built from a converted church.

It wasn't a great place to work in. The big room, the big church hall was not a nice sound. Led Zeppelin were in the studio underneath in the crypt, which was much smaller and cozier and had a very neutral sound. That was a much easier place to work in. They had it pretty blocked out for their session. We were in there maybe just once—we managed to get in to record there.

But, yeah, it was a tricky album to make, and at the end of it, I wasn't really sure if it would be well-received, but it did OK. In the months and, indeed, the years following the release, it did much more than OK. It wasn't a really slow album, but it was a slow burn. It created a stir, but it was particularly in the year or two following the release that it became a flagship for Jethro Tull throughout the world.

Ian Anderson and Martin Barre in 1971.

What was the germ of the idea behind the title track? I understand you and your then-wife wrote it together, but what compelled you to write about a homeless person so poetically?

A photograph that she had taken. She was studying photography in London at the time and came back with some photographs of homeless people in the south of London. One particular one caught my eye and I said, "Let's write a song about this guy." Not trying to imagine much about his life, but more in terms of our reaction to the homeless.

I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel—compassion, fear, embarrassment. It's a very mixed and contradictory set of emotions, but I think part of the way of dealing with these things is to try to understand why you feel those things. Some of them are reasonable, perhaps, and some of them are unreasonable.

But the song itself was one of the probably only two occasions I can think of in my life where I wrote a song with somebody else. Actually, that's not quite true—there were two or three very early songs I co-wrote with Mick Abrahams, our guitar player in the first year of Jethro Tull. But that's not something I normally do. I'm very private as a songwriter and find it much easier to be in isolation—in intellectual quarantine.

Aqualung is full of cynicism about organized religion. In past years, you've performed in churches and been involved in their preservation. But back in 1971, where was your head regarding that subject?

Oh, very much the same as it is today. I have a natural cynicism and questioning about all aspects of organized religion. It doesn't stop me from ultimately being a great supporter of Christianity in all of its many flavors. I thoroughly support the church, especially as we go through—I mean, 50 years ago, congregations were beginning to suffer, but the church still had pretty good attendance.

These days, it really is an enormous struggle in a very secular world to give people the options. So many churches these days are financially at the tipping point of having to fail or go bankrupt. Some of the cathedrals in the U.K. I played in to raise money for them have been literally at the point of having to close them down, just because of lack of support and, ultimately, lack of a congregation.

I mean, there are some fairly well-off, big cathedrals that charge entrance fees because they are historic buildings or very grand, but the lesser cathedrals and most churches don't have any income except for the generosity of visitors. Of course, that mainly means the regular congregation leaving some money, and sometimes, a legacy from somebody who can afford to leave money behind for posterity.

But it costs a lot of money to keep these places going. Even a little village church may still technically be open, but they only have a service once a month because they don't have a permanent priest. They have maybe a priest who looks after several different parishes and travels around taking it in turns to do a Sunday service.

It's tough times, and I'm very much in support of the idea that we should have that freedom to go into those historic buildings, which most of them are. In America, perhaps, not so, because you're a very young country. But a little village church somewhere could be a thousand years old.

It goes back, really, to Norman times. A lot of churches built in, say, 1100 or 1200, maybe they've changed a little bit along the way architecturally or the building of a new tower or chapel or whatever, but many of them really are between 500 and 1,000 years old, and that's something I think is something worth hanging onto while they still exist. Because one thing's for sure: we aren't going to build any more.

The Victorians did. The Victorians built a few big Gothic churches that were in the style of grand European churches, and so there are a few cathedrals in the U.K. that were built in 1700 crossing into 1800. By the mid-1800s, there was a revival in Gothic architecture, so the cathedrals that follow into the mid-1800s through to the turn of the century tend to be quite grand buildings. But I often feel they lack the buzz. They lack the atmosphere and the special spiritual charge of the truly ancient cathedrals.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//sqqfOcTsReI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

To me, what you're saying is reflected in "Wind Up." In that song, you're not bilious toward faith as a whole. Rather, you seem almost defensive of the essence of it—God, or the idea of God.

Yeah. I don't think we want to overstate it, but I remember the first time I went to the Vatican when I first traveled to Italy. I lasted about five minutes because I just found it so opulent and over-the-top.

Catholicism does celebrate everything to do with art and gold-plated ornamentation. I found it very hard coming from a Protestant background in the Scottish-English churches, which were more Lutheran in their origins. Simpler, without a lot of ornamentation. So, I found Catholicism overwhelming and too obsessed with grandeur.

I don't feel that way any longer. Many of the churches in Europe that I've visited and managed to go perform in are indeed Catholic churches. I'm perhaps more relaxed about the way in which people celebrate that because a lot of relatively poor, ordinary people see this as a symbol of the thing they can never aspire to having in terms of their own surroundings. That opulence, that grandeur gives them some comfort and tuning-in to the greatness of God, as they are taught.

But I'm not a believer. I must say. I'm not somebody who has faith, as such. I don't believe in certainties. I believe in possibilities and, occasionally, I believe in probabilities. So, if you were to put me on the scale of agnosticism of one to 10, you could probably put me down for a six, maybe a seven on a good day, in terms of confidence about there being that absolute cosmic power that we call God.

While I greatly value the Bible, I view it as a gateway to spirituality in the same way that Islam is a gateway to spirituality and Hinduism and the world's great religions. They shouldn't be seen as absolute in terms of detail and being the only way to the truth.

I find more acceptance in the idea that they are all different doors entering the same great building. You can come through the side door, the front door, the back door or descend from the rafters. There are lots of ways in. That's how I see religion. I place value on it, but I don't like it being pushed to me as a message of absolute certainty.

As a child at school—14 years old, or whatever I was—I began to have feelings about the way I was being taught in regard to religion that expressed themselves in songs like "My God" and "Wind Up," for example.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//TSkxvvgMAGQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

And a lot of Aqualung's power lies in how it deals not only with big subjects, but small, almost mundane ones. "Wond'ring Aloud" portrays this quiet, domestic scene. What was going on in that song?

Well, it's as simple as it is. I don't very often write love songs, as such, and that is. It's a simple, calm, domestic, comfortable, cozy-warm-blanket kind of a song. A bit of a rarity for me. I tend to be more in social realism, in terms of subject matter, but I do stretch to the more whimsical, surreal songs like "Mother Goose." And songs where I'm actually giving you a little more of an insight into my own emotions.

But mostly, I'm writing about people in a landscape—almost like actors on a theater stage. I don't do close-ups of people. I don't do pure landscapes without people. I like to study people in the context in which I see them. And that comes probably from my earlier years studying painting and drawing and, indeed, photography. I see things with the eye of a photographer or a painter, and then I put them to music and words.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//64k6cZ9fGpg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

That perfectly encapsulates "Locomotive Breath," which sets characters against a wider landscape of capitalism run amok. Which is a theme you returned to later on with "Farm on the Freeway."

Well, the subject matter, yes, indeed. Things evolve, things change. We carry on with our expansion in terms of population and global economics. It's the reality that we have to face.

But if there's one thing I think "Locomotive Breath" is about, it's more about population growth rather than anything else. It's talking about the material world, but as a result of a growing population, one which seemed, back in 1970, to be out of control. And if it seemed like that in 1970—well, goodness, it seems a lot more so now!

Think about it this way. When I was born back in 1947, compared to now, the population of Earth has grown quite a bit. And if you were to ask the question, "Well, how much? 50%? 100%?" you would be surprised, I would expect, for me to tell you that since I was born, within the lifetime of one person—hopefully well within the lifetime of one person, in my case!—the population of planet Earth has slightly more than tripled. That should give pause for thought. In onegeneration, three times the population.

It clearly can't go on. There are signs, of course, that population growth in the so-called civilized Western world is slowing down. That the growth is below the threshold of sustainability, in the sense of fertility rates falling well below two through most of Europe.

Perhaps not in America, where people like to have big families and brag about them. But in the pragmatic world of European countries and many countries elsewhere that are not technically part of Europe but within that great landmass, you see populations diminishing because people choose not to have large families.

And so many women decide, given that they have a degree of freedom and the ability to be part of the choice, which they certainly didn't have 100 years ago. Now, they do, and they choose to have one child. Maybe two. Sometimes no children at all. So, on average, that falls to somewhere around 1.6 in the fertility rate on average around Europe.

But of course, in countries, particularly in Africa, we see that the fertility rate is somewhere up around five, six, seven. It continues to explode and brings with it, of course, overpopulation in some areas and the desperation to migrate from those areas to areas where people feel they have a better chance of survival and doing well. Add in climate change to that, and we have a recipe for mass migration in the next 50 years that will dwarf anything you've seen so far.

I would think Canada will be thinking of building a wall between the U.S.A. and Canada to stop you horny Americans from getting in!

Jethro Tull live in Germany, 1971.

Overpopulation was on your mind 50 years ago, and it still is. So were these themes of love and whimsy and religious hypocrisy. Then and now, did audiences have an accurate read on what you were trying to convey with Aqualung?

I don't really think I've ever given a great deal of thought to what audiences think or even what they want. It's not something that has ever driven me. It's an afterthought if, indeed, it's a thought at all.

I do remember finishing the Aqualung album. After the very last session, it was so late in the night it was early morning, and the keyboard player John Evans and I went into a little cafe near Basing St. in London where the studio was, that had just opened, to do a very early breakfast.

I remember saying to John, "What do you think? Do you think this is going to play well with our audiences and record-buyers and fans and the media?" He scratched his head and said, "I have absolutely no idea." I said, "Well, I'm a bit nervous, you know. I have my doubts it's going to hit the mark."

It was a bit nerve-wracking for the next month or two until the album was released. I did have my doubts that it was going to be a step upward from our previous album, Benefit. Either it was going to be the beginning of a new ascent to greater, loftier success, or it was going to be the beginning of the downhill slide.

I felt it was an important album and it was relatively well-received at the time of its release in the U.K, but not overwhelmingly so. I think some of the subject material put some people off. But it was important that over the next year or two, it really did consolidate the onward surge of Jethro Tull's success in global terms.

I mean, not global. It never did anything in China! But throughout Eastern Europe and Latin America and other places, it caught on.

But throughout Eastern Europe and Latin American places, it caught on. It might have taken a few more years to have penetrated. But Aqualung, by the mid-'70s, had become a very important and popular album throughout the European landmass, including Russia, and places where culture was very much not permitted.

So, along with everything else, our music was banned in several countries, and it was only heard by people prepared to smuggle in bought, black-market copies, and make illegal tape copies to listen to. I do sometimes feel a sense of awe, really, in the degree to which people grew up, listening to Western rock music in defiance of the law. And potentially, a breach that would put them in prison. Or indeed, in Pinochet's Chile, even worse.

So I thanked Mikhail Gorbachev personally when I met him some ten, 12 years ago, for being the man behind Glasnost and Perestroika. On his watch, Jethro Tull and The Beatles were the first acts from the West to be officially released on the Russian state record label Melodiya.

Was the record banned for its religious commentary? What was the deal there?

In some places, it was. For example, in Spain, in the final dying moments of Franco's fascist regime, it was indeed banned from the radio. Some words were bleeped out as well. I remember in the Bible Belt of the U.S.A., people were burning copies of Aqualung.

Jesus.

In the Evangelical South, it was seen to be sacrilegious and attracted a fair amount of attention. It had a little bit of notoriety attached to it. But, in Russia, it was just Western music generally. As indeed in some of the world's other countries, it was forbidden, verboten, because it was Western, decadent rock music, and it could seduce the youth and cause mayhem, madness, upheaval and revolution.

But in Gorbachev's time, I think he wisely released that it was time to gently release the safety valve and create a bit more freedom. And while, of course, he had nothing whatsoever to do with saying, "Oh, we'll release Jethro Tull. I've always liked them!" That's not what happened. It was just, he created an atmosphere where that could come about.

And so, I think we saw the end result is not only a growth of popularity and accessibility of Western rock music, but it also encouraged many of the homegrown rock bands to actively and more publicly pursue their dreams without fear of arrest. Which is a good thing.

Ian Anderson imitating the Aqualung cover art in 2011.

That level of censorship is alarming to me. Because it's not a record of blunt, ugly atheism; it's yearning and nuanced on that subject. Do you feel this one-dimensional attitude has taken hold in the 21st century as well?

I think I find that one-dimensional attitude liberally dispensed around the Old Testament of the Holy Book. That's what people go for. They like things black-and-white, and simple and direct, and they like a little bit of fear and diatribe and retribution thrown in. It's what happens.

But, of course, in our much more accessible world in terms of media, and social media in particular, people are able to express views instantly, loudly, even if sometimes they might regret them. And black-and-white is the order of the day, so everything is polarized and divisive.

And I think, America, perhaps, more than any country in the world is an absolute demonstration of that, in terms of the way politics have divided a nation. And the degree to which people might have had a genuine and positive and valuable feeling of loyalty to their country, it's become so split and polarized that I think past ways of looking at it have now become very hard to grasp.

Being a two-party system unlike Europe where there are many parties—and obviously, coalitions come about as a result of the failure of any party to achieve a massive level of superiority. In your country, it's essentially two parties, first past the post, and that's it. But, in fact, it's not it because, of course, you then contest the election result, and claim it was stolen.

So, it's a tough world these days, and I think we have a real problem on our hands, collectively. Not just in the U.S.A., but collectively, as a result of populist politics and the divisiveness that seems to go with it.

If we're not allowed to unpack and examine these complicated subjects as you did on Aqualung, we're going to have a sad, withered society. How do we restore nuance to the public discourse so we're not firing professors over tweets?

I think it is exactly by that. By having conversations as opposed to ranting and raving on Twitter, which does no good for anybody. I think it's about listening to other peoples' points of view and trying to understand them, even if don't agree with them. If you don't arrive at an agreement, at least you've hopefully had a conversation and let people know how and why you have the views that you do.

Because to some extent, it is about the media environment. As you say, societal norms that you've grown up in.

Is the problem that we often smear the person or write them off before the conversation begins?

Yeah. I think you've got to give people a chance, and sometimes you have to be discrete, and you can't always say what's on your mind.

I think my views of the Republican Party are of something a little bit more traditional, conservative, discrete, and gentlemanly. You can't actually describe the U.S. Senate in those terms today!

It's a little bent out of shape, and I personally think it's going to take a lot of calming down. People have to calm themselves down. But sore losers like Ted Cruz, or indeed Donald Trump, they're not going quietly into the background, they only see further opportunities to be exhibiting their extreme views, and trying to grab a bit more power. So, it's a scary world.

Ian Anderson live in Berlin, 2018.

I have a bit of a soft spot for George W. Bush. I felt he had a kind of gentlemanly spirit about him and a restraint. I don't know if you've ever read his book after his presidency was over. I'm assuming he didn't sit there and write every word himself, but it seemed very much the genuine sentiments of somebody who had, at least, painstakingly done it through a series of interviews. Or perhaps he had typed a lot of it out himself; I really don't know.

But it was, I think, a mark of the man, that he demonstrated a degree of his own failings, his dependence, as a U.S president, on listening to the advice coming from people around him. Obviously, notably Rumsfeld and Cheney. He didn't badmouth them, but you could tell from his book that he was circumspect, I think, in hindsight, about some of the things that he was given to work with.

He wasn't a great president, but he certainly wasn't a bad one. The world would be a much better place, right now, with George W. Bush as U.S president, than the previous one. And we are at this point, now, where we've got your oldest president—or to become president—the oldest man in historical terms to probably serve only a single term, before he has to hand it over to younger blood.

But boy, did he inherit the second-worst gig on planet Earth right now! In a pandemic year, or two, to try to gradually bring America back to some kind of prosperity, and a degree of normalcy, against all the odds. And everybody's waiting to find every potential failing to try and make him look ineffectual. It's the second toughest gig on planet Earth.

And in case you weren't going to ask me, "Well, who's got the worst gig on planet Earth?" I'll tell you. It's Frank! Pope Francis! It's a really rough time to be the Pope. Because you're presiding over what appears, to many, to be a sinking ship. Catholicism throughout the world is losing ground rapidly, and his role can't be to overturn things at a single throw. It's got to be gentle and gradual.

Just like the U.S president has to work with the House of Representatives and the Senate, the Pope has to work with his cardinals, and indeed, throughout the world, with a lot of people who view him as being far too liberal. So, it's a tough gig, and I don't envy his role at all. Nonetheless, I think he's definitely, in my world, a great improvement over the last few.

You just laid out nuanced portraits of complicated, often vilified figures. To me, that spirit of conciliation runs deep in Aqualung. And Steven Wilson's excellent remix [from 2011] means we can commune with that message more directly than ever.

I'm not sure that it demonstrates itself as well as it might, when you listen to it only on Spotify, let's say.

What Steven has done, being a sensitive and careful person, with great respect for the music as it was originally unveiled, all that time ago—not just our music, but other people that he's worked with, on remixing. What he does is to clarify, to put a little sparkle into the audio by cleaning everything up, to get rid of all those hums and buzzes and clicks and bits of spurious noise between passages of music that the analog world couldn't do.

In digital terms, you can create so much more transparency with the old analog tapes, if you just patiently go back, tidying everything up, so that you hear what you hear, only when it has something to say, rather than being 24 tracks of crumbling, rumbling, spurious tape noise and hiss.

But he doesn't mess too much with either the stereo layout of the instruments or, indeed the balance of the instruments. He takes the original mixes as his model and refines it with great care and discipline, and above all, I think, respect for the original work. It's at its best when you hear it in a high-quality digital format, but for most people, of course, it's an MP3, or it's streaming from some platform.

You probably still discern the differences, but it's at its best when you listen to it in higher quality. Even a very well-cut and -pressed vinyl album has a certain quality about it, these days. Much better than it did, back when I used to do it, in the '70s. Even though they're still using 1960s Neumann cutting lathes in the studios of the world, are still cut, master lacquers, for the industry. Even though it's ancient equipment, it's better understood, and it's maintained meticulously by people who are invariably music fans.

These days, you go into a cutting room, there's no smoking, there's no everything, it's air-conditioned, clean air, no dust, no mess, nothing to potentially ... It's more like laboratory conditions. And I saw that, actually, in Japan, when I went there, to JVC studios, in the early days of quadraphonic sound, and cutting the very first quadraphonic albums. Everybody was wearing face masks and white coats!

And I loved doing it back then; back in the early '80s. But the reality is that, these days, people take it so much more seriously, to get a good, clean, tidy cut. And they can do it. But, in the '70s, George "Porky" Peckham, one of the most famous cutting engineers that I used to work with, cut all the Led Zeppelin albums, as well as Jethro Tull, and a whole host of... everybody, I suppose, at that time.

He always had a cigarette in his mouth, and he would lean over the master lacquer, peering through the microscopy to check the grooves, with ash dropping onto the master. So it would probably be true to say there are probably some Led Zeppelin albums where you can't smell George Peckham's cigarette, but you can hear it! Little bits of ash that found their way into the groove and had got pressed!

That's all I've got, Ian. Thank you so much.

Well, nice to talk to you. Take care. Hopefully, in months and years to come, the music industry will be back to some kind of positive and fruitful level of activity again in the U.S.A. We're nowhere near that yet, that's for sure. Maybe six months from now, I think, you should be, hopefully, in a position to begin to do concerts again.

We have a U.K theater tour booked in September, which I'm hopeful we will be able to do. But, every week that goes by, we cancel or postpone concerts into 2022, which we've already postponed since 2020. We're having to push them even further away since they're not going to be feasible for the next three or four months.

We'll try and keep optimistic, and hope that we can all get back on the road.

Dave Mason On Recording With Rock Royalty & Why He Reimagined His Debut Solo Album, 'Alone Together'

.jpg)

Photo: Yoko Ono

list

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

John Lennon's 1973 solo album 'Mind Games' never quite got its flowers, aside from its hit title track. A spectacular 2024 remix and expansion is bound to amend its so-so reputation.

As the train of Beatles remixes and expansions — solo or otherwise — chugs along, a fair question might come to mind: why John Lennon's Mind Games, and why now?

When you consider some agreed-upon classics — George Harrison's Living in the Material World, Ringo Starr's Ringo — it might seem like it skipped the line. Historically, fans and critics have rarely made much of Mind Games, mostly viewing it as an album-length shell for its totemic title track.

The 2020 best-of Lennon compilation Gimme Some Truth: The Ultimate Mixes featured "Mind Games," "Out the Blue," and "I Know (I Know)," which is about right — even in fanatical Lennon circles, few other Mind Games tracks get much shine. It's hard to imagine anyone reaching for it instead of Plastic Ono Band, or Imagine, or even the controversial, semi-outrageous Some Time in New York City.

Granted, these largely aren't A-tier Lennon songs — but still, the album's tepid reputation has little to do with the material. The original Mind Games mix is, to put it charitably, muddy — partly due to Lennon's insecurity about his voice, partly just due to that era of recordmaking.

The fourth-best Picasso is obviously still worth viewing. But not with an inch of grime on your glasses.

The Standard Deluxe Edition. Photo courtesy of Universal Music Group

That's all changed with Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection — a fairly gobsmacking makeover of the original album, out July 12. Turns out giving it this treatment was an excellent, long-overdue idea — and producer Sean Ono Lennon, remixers Rob Stevens, Sam Gannon and Paul Hicks were the best men for the job. Outtakes and deconstructed "Elemental" and "Elements" mixes round out the boxed set.

It's not that Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection reveals some sort of masterpiece. The album's still uneven; it was bashed out at New York's Record Plant in a week, and it shows. But that's been revealed to not be its downfall, but its intrinsic charm. As you sift through the expanded collection, consider these reasons you should give Mind Games another shot.

The Songs Are Better Than You Remember

Will deep cuts like "Intuition" or "Meat City" necessarily make your summer playlist? Your mileage may vary. However, a solid handful of songs you may have written off due to murky sonics are excellent Lennon.

With a proper mix, "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" absolutely soars — it's Lennon's slow-burning, Smokey Robinson-style mea culpa to Yoko Ono. "Bring On the Lucie (Freda Peeple)" has a rickety, communal "Give Peace a Chance" energy — and in some ways, it's a stronger song than that pacifist classic.

And on side 2, the mellow, ruminative "I Know (I Know)" and "You Are Here" sparkle — especially the almost Mazzy Star-like latter tune, with pedal steel guitarist "Sneaky" Pete Kleinow (of Flying Burrito Brothers fame) providing abundant atmosphere.

And, of course, the agreed-upon cuts are even better: "Mind Games" sounds more celestial than ever. And the gorgeous, cathartic "Out the Blue" — led by David Spinozza's classical-style playing, with his old pal Paul McCartney rubbing off on the melody — could and should lead any best-of list.

The Performances Are Killer

Part of the fun of Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is realizing how great its performances are. They're not simply studio wrapping paper; they capture 1970s New York's finest session cats at full tilt.

Those were: Kleinow, Spinozza, keyboardist Ken Ascher, bassist Gordon Edwards, drummer Jim Keltner (sometimes along with Rick Marotta), saxophonist Michael Brecker, and backing vocalists Something Different.

All are blue-chip; the hand-in-glove rhythm section of Edwards and Keltner is especially captivating. (Just listen to Edwards' spectacular use of silence, as he funkily weaves through that title track.)

The hardcover book included in Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is replete with the musicians' fly-on-the-wall stories from that week at the Record Plant.

"You can hear how much we're all enjoying playing together in those mixes," Keltner says in the book, praising Spinozza and Gordon. "If you're hearing John Lennon's voice in your headphones and the great Kenny Ascher playing John's chords on the keys, there's just no question of where you're going and how you're going to get there."

It Captures A Fascinating Moment In Time

"Mind Games to me was like an interim record between being a manic political lunatic to back to being a musician again," Lennon stated, according to the book. "It's a political album or an introspective album. Someone told me it was like Imagine with balls, which I liked a lot."

This creative transition reflects the upheaval in Lennon's life at the time. He no longer had Phil Spector to produce; Mind Games was his first self-production. He was struggling to stay in the country, while Nixon wanted him and his message firmly out.

Plus, Lennon recorded it a few months before his 18-month separation from Ono began — the mythologized "Lost Weekend" that was actually a creatively flourishing time. All of this gives the exhaustive Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection historical weight, on top of listening pleasure.

"[It's important to] get as complete a revealing of it as possible," Stevens, who handled the Raw Studio Mixes, tells GRAMMY.com. "Because nobody's going to be able to do it in 30 years."

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Central Park, 1973. Photo: Bob Gruen

Moments Of Inspired Weirdness Abound

Four seconds of silence titled the "Nutopian International Anthem." A messy slab of blues rock with refrains of "Fingerlickin', chicken-pickin'" and "Chickin-suckin', mother-truckin'." The country-fried "Tight A$," basically one long double entendre.

To put it simply, you can't find such heavy concentrates of Lennonesque nuttiness on more commercial works like Imagine. Sometimes the outliers get under your skin just the same.

It's Never Sounded Better

"It's a little harsh, a little compressed," Stevens says of the original 1973 mix. "The sound's a little bit off-putting, so maybe you dismiss listening to it, in a different head. Which is why the record might not have gotten its due back then."

As such, in 2024 it's revelatory to hear Edwards' basslines so plump, Keltner's kick so defined, Ascher's lines so crystalline. When Spinozza rips into that "Aisumasen" solo, it absolutely penetrates. And, as always with these Lennon remixes, the man's voice is prioritized, and placed front and center. It doesn't dispose of the effects Lennon insecurely desired; it clarifies them.

"I get so enthusiastic," Ascher says about listening to Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection. "I say, 'Well, that could have been a hit. This could have been a hit. No, this one could have been a hit, this one." Yes is the answer.

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

From Brian Wilson's obsession with "Be My Baby" and the Wall Of Sound, to the group's complicated relationship with Murry Wilson and Dennis Wilson's life in the counterculture, 'The Beach Boys' is rife with insights from the group's first 15 years.

It may seem like there's little sand left to sift through, but a new Disney+ documentary proves that there is an endless summer's worth of Beach Boys stories to uncover.

While the legendary group is so woven into the fabric of American culture that it’s easy to forget just how innovative they were, a recently-released documentary aims to remind. The Beach Boys uses a deft combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews to introduce a new generation of fans to the band.

The documentary focuses narrowly on the first 15 years of the Beach Boys’ career, and emphasizes what a family affair it was. Opening the film is a flurry of comments about "a certain family blend" of voices, comparing the band to "a fellowship," and crediting the band’s success directly to having been a family. The frame is apt, considering that the first lineup consisted of Wilson brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl, their cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine, and their first manager was the Wilsons’ father, Murry.

All surviving band members are interviewed, though a very frail Brian Wilson — who was placed under a conservatorship following the January death of his wife Melinda — appears primarily in archival footage. Additional perspective comes via musicians and producers including Ryan Tedder, Janelle Monáe, Lindsey Buckingham, and Don Was, and USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun.

Thanks to the film’s tight focus and breadth of interviewees, it includes memorable takeaways for both longtime fans and ones this documentary will create. Read on for five takeaways from Disney+'s The Beach Boys.

Family Is A Double-Edged Sword

For all the warm, tight-knit imagery of the Beach Boys as a family band, there was an awful lot of darkness at the heart of their sunny sound, and most of the responsibility for that lies with Wilson family patriarch Murry Wilson. Having written a few modest hits in the late 1930s, Murry had talent and a good ear, and he considered himself a largely thwarted genius.

When Brian, Dennis, and Carl formed the Beach Boys with their cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine, Murry came aboard as the band’s manager. In many respects, he was capable; his dogged work ethic and fierce protectiveness helped shepherd the group to increasingly high profile successes. He masterminded the extended Wilson family call-in campaign to a local radio station, pushing the Beach Boys’ first single "Surfin’" to become the most popular song in Los Angeles. He relentlessly shopped their demos to music labels, eventually landing them a contract at Capitol Records. He supported the band’s strong preference to record at Western Recordings rather than Capitol Records’ own in-house studio, and was an excellent promoter.

Murry Wilson was also extremely controlling, fining the band when they made mistakes or swore, and "was miserable most of the time," according to his wife Audree.

Footage from earlier interviews with Carl and Dennis, and contemporary comments from Mike Love make it clear that Murry was emotionally and physically abusive to his sons throughout their childhoods. He even sold off the Beach Boys’ songwriting catalog without consulting co-owner Brian, a moment that Brian’s ex-wife Marilyn says he felt so keenly that he took to his bed and didn’t get up for three days.

Murry Wilson was at best a very complicated figure, both professionally jealous of his own children to a toxic degree and devoted to ensuring their success.

"Be My Baby" and The Wrecking Crew Changed Brian Wilson’s Life

"Be My Baby," which Phil Spector had produced for the Ronettes in 1963, launched the girl group to immediate iconic status. The song also proved life-changing for Brian. On first hearing the song, "it spoke to my soul," and Brian threw himself into learning how Spector created his massive, lush Wall of Sound. Spector’s approach taught Brian that production was a meaningful art that creates an "overall sound, what [the listeners] are going to hear and experience in two and a half minutes."

By working with The Wrecking Crew — a truly motley bunch of experienced, freewheeling musicians who played on Spector’s records and were over a decade older than the Beach Boys — Brian’s artistic sensibility quickly emerged. According to drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Carol Kaye, Brian not knowing what he didn’t know gave him the freedom and imagination to create sounds that were completely new and innovative.

Friendly Rivalries With Phil Spector & The Beatles Yielded Amazing Pop Music

According to popular myth, the Beach Boys and the Beatles saw each other exclusively as almost bitter rivals for the ears, hearts, and disposable income of their fans. The truth is more nuanced: after the initial shock of the British Invasion wore off, the two groups developed and maintained a very productive, admiration-based competition, each band pushing the other to sonic greatness.

Cultural historian and academic Josh Kun reframes the relationship between the two bands as a "transatlantic collaboration," and asks, "If they hadn’t had each other, would they have become what they became?" Could they have made the historic musical leaps that we now take for granted?

Read more: 10 Memorable Oddities By The Beach Boys: Songs About Root Beer, Raising Babies & Ecological Collapse

The release of Rubber Soul left Brian Wilson thunderstruck. The unexpected sitar on "Norwegian Wood," the increasingly mature, personal songwriting, all of it was so fresh that "I flipped!" and immediately wanted to record "a thematic album, a collection of folk songs."

Brian found life on the road soul-crushing and terrifying, and was much more content to stay home composing, writing, and producing. With the touring band out on the road, and with a creative fire lit under him by both the Beatles and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, he had time to develop into a wildly creative, exacting, and celebrated producer, an experience that yielded the 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds.

Pet Sounds Took 44 Years To Go Platinum

You read that right: Pet Sounds was a flop in the U.S. upon its release. Even after hearing radio-ready tracks like "Wouldn’t It Be Nice?" and "Sloop John B" and the ravishing "God Only Knows," Capitol Records thought the album had minimal commercial potential and didn’t give it the promotional push the band were expecting. Fans in the United Kingdom embraced it, however, and the votes of confidence from British fans — including Keith Moon, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney — buoyed both sales and the Beach Boys’ spirits.

In fact, Lennon and McCartney credited Pet Sounds with giving them a target to hit when they went into the studio to record the Beatles’ own next sonically groundbreaking album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As veteran producer and documentary talking head Don Was puts it, Brian Wilson was a true pioneer, incorporating "textures nobody had ever put into pop music before." The friendly rivalry continued as the Beatles realized that they needed to step up their game once more.

Read more: Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds,' The Beatles, Paul McCartney

Meanwhile, Capitol Records released and vigorously promoted a best-of album full of the Beach Boys’ early hits, Best Of The Beach Boys. The collection of sun-drenched, peppy tunes was a hit, but was also very out of step with the cultural and political shifts bubbling up through the anti-war and civil rights movements of the era. Thanks in part to later critical re-appraisals and being publicly embraced by musicians as varied as Questlove and Stereolab, Pet Sounds eventually reached platinum status in April 2000, 44 years after its initial release.

Dennis Wilson Was The Only Truly Beachy Beach Boy

Although the Beach Boys first made a name for themselves as purveyors of "the California sound" by singing almost exclusively about beaches, girls, and surfing, the only member of the band who really liked the beach was drummer Dennis Wilson.

Al Jardine ruefully recalls that "the first thing I did was lose my board — I nearly drowned" on a gorgeous day at Manhattan beach. Dennis was an actual surfer whose tanned, blonde good looks and slightly rebellious edge made him the instant sex symbol of the group. In 1967, when Brian’s depression was the deepest and he relinquished in-studio control of the band, Dennis flourished musically and lyrically. Carl Wilson, who had emerged as a very capable producer in Brian’s absence, described Dennis as evolving artistically "really quite amazingly…it just blew us away."

Dennis was also the only Beach Boy who participated meaningfully in the counterculture of the late 1960s, a movement the band largely sat out of, largely to the detriment of their image. He introduced the band to Transcendental Meditation — a practice Mike Love maintains to this day — and was a figure in the Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon music scenes. Unfortunately, he also became acquainted with and introduced his bandmates to Charles Manson. Manson’s true goal was rock stardom; masterminding the gruesome mass murders that his followers perpetrated in 1969 was a vengeful outgrowth of his thwarted ambition.

The Beach Boys did record and release a reworked version of one of Manson’s songs, "Never Learn Not To Love" as a B-side in 1968. Love says that having introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher, who firmly rebuffed the would-be musician, "weighed on Dennis pretty heavily," and while Jardine emphatically and truthfully says "it wasn’t his fault," it’s easy to imagine those events driving some of the self-destructive alcohol and drug abuse that marked Dennis’ later years.

The Journey From Obscurity To Perennially Popular Heritage Act

The final minutes of The Beach Boys can be summed up as "if all else fails commercially, release a double album of beloved greatest hits." The 1970s were a very fruitful time for the band creatively, as they invited funk specialists Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band and relocated to the Netherlands to pursue a harder, more far-out sound. Although the band were proud of the lush, singer/songwriter material they were recording, the albums of this era were sales disappointments and represented a continuing slide into uncoolness and obscurity.

Read more: Brian Wilson Is A Once-In-A-Lifetime Creative Genius. But The Beach Boys Are More Than Just Him.

Once again, Capitol Records turned to the band’s early material to boost sales. The 1974 double-album compilation Endless Summer, comprised of hits from 1962-1965, went triple platinum, relaunching The Beach Boys as a successful heritage touring act. A new generation of fans — "8 to 80," as the band put it — flocked to their bright harmonies and upbeat tempos, as seen in the final moments of the documentary when the Beach Boys played to a crowd of over 500,000 fans on July 4, 1980.

While taking their place as America’s Band didn’t do much to make them cool, it did ensure one more wave of chart success with 1988’s No. 1 hit "Kokomo" and ultimately led to broader appreciation for Pet Sounds and its sibling experimental albums like Smiley Smile. That wave of popularity has proven remarkably durable; after all, they’ve ridden it to a documentary for Disney+ nearly 45 years later.

Listen: 50 Essential Songs By The Beach Boys Ahead Of "A GRAMMY Salute" To America's Band

Photo: Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd

list

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

More than five decades after its 1970 release, Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 'Let it Be' film is restored and re-released on Disney+. With a little help from the director himself, here are some less-trodden tidbits from this much-debated film and its album era.

What is about the Beatles' Let it Be sessions that continues to bedevil diehards?

Even after their aperture was tremendously widened with Get Back — Peter Jackson's three-part, almost eight hour, 2021 doc — something's always been missing. Because it was meant as a corrective to a film that, well, most of us haven't seen in a long time — if at all.

That's Let it Be, the original 1970 documentary on those contested, pivotal, hot-and-cold sessions, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Much of the calcified lore around the Beatles' last stand comes not from the film itself, but what we think is in the film.

Let it Be does contain a couple of emotionally charged moments between maturing Beatles. The most famous one: George Harrison getting snippy with Paul McCartney over a guitar part, which might just be the most blown-out-of-proportion squabble in rock history.

But superfans smelled blood in the water: the film had to be a locus for the Beatles' untimely demise. To which the film's director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, might say: did we see the same movie?

"Looking back from history's vantage point, it seems like everybody drank the bad batch of Kool-Aid," he tells GRAMMY.com. Lindsay-Hogg had just appeared at an NYC screening, and seemed as surprised by it as the fans: "Because the opinion that was first formed about the movie, you could not form on the actual movie we saw the other night."

He's correct. If you saw Get Back, Lindsay-Hogg is the babyfaced, cigar-puffing auteur seen throughout; today, at 84, his original vision has been reclaimed. On May 8, Disney+ unveiled a restored and refreshed version of the Let it Be film — a historical counterweight to Get Back. Temperamentally, though, it's right on the same wavelength, which is bound to surprise some Fabs disciples.

With the benefit of Peter Jackson's sound-polishing magic and Giles Martin's inspired remixes of performances, Let it Be offers a quieter, more muted, more atmospheric take on these sessions. (Think fewer goofy antics, and more tight, lingering shots of four of rock's most evocative faces.)

As you absorb the long-on-ice Let it Be, here are some lesser-known facts about this film, and the era of the Beatles it captures — with a little help from Lindsay-Hogg himself.

The Beatles Were Happy With The Let It Be Film

After Lindsay-Hogg showed the Beatles the final rough cut, he says they all went out to a jovial meal and drinks: "Nice food, collegial, pleasant, witty conversation, nice wine."

Afterward, they went downstairs to a discotheque for nightcaps. "Paul said he thought Let it Be was good. We'd all done a good job," Lindsay-Hogg remembers. "And Ringo and [wife] Maureen were jiving to the music until two in the morning."

"They had a really, really good time," he adds. "And you can see like [in the film], on their faces, their interactions — it was like it always was."

About "That" Fight: Neither Paul Nor George Made A Big Deal

At this point, Beatles fanatics can recite this Harrison-in-a-snit quote to McCartney: "I'll play, you know, whatever you want me to play, or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you… I'll do it." (Yes, that's widely viewed among fans as a tremendous deal.)

If this was such a fissure, why did McCartney and Harrison allow it in the film? After all, they had say in the final cut, like the other Beatles.

"Nothing was going to be in the picture that they didn't want," Lindsay-Hogg asserts. "They never commented on that. They took that exchange as like many other exchanges they'd had over the years… but, of course, since they'd broken up a month before [the film's release], everyone was looking for little bits of sharp metal on the sand to think why they'd broken up."

About Ringo's "Not A Lot Of Joy" Comment…

Recently, Ringo Starr opined that there was "not a lot of joy" in the Let it Be film; Lindsay-Hogg says Starr framed it to him as "no joy."

Of course, that's Starr's prerogative. But it's not quite borne out by what we see — especially that merry scene where he and Harrison work out an early draft of Abbey Road's "Octopus's Garden."

"And Ringo's a combination of so pleased to be working on the song, pleased to be working with his friend, glad for the input," Lindsay-Hogg says. "He's a wonderful guy. I mean, he can think what he wants and I will always have greater affection for him.

"Let's see if he changes his mind by the time he's 100," he added mirthfully.

Lindsay-Hogg Thought It'd Never Be Released Again

"I went through many years of thinking, It's not going to come out," Lindsay-Hogg says. In this regard, he characterizes 25 or 30 years of his life as "solitary confinement," although he was "pushing for it, and educating for it."

"Then, suddenly, the sun comes out" — which may be thanks to Peter Jackson, and renewed interest via Get Back. "And someone opens the cell door, and Let it Be walks out."

Nobody Asked Him What The Sessions Were Like

All four Beatles, and many of their associates, have spoken their piece on Let it Be sessions — and journalists, authors, documentarians, and fans all have their own slant on them.

But what was this time like from Lindsay-Hogg's perspective? Incredibly, nobody ever thought to check. "You asked the one question which no one has asked," he says. "No one."

So, give us the vibe check. Were the Let it Be sessions ever remotely as tense as they've been described, since man landed on the moon? And to that, Lindsay-Hogg's response is a chuckle, and a resounding, "No, no, no."