The first New Music Friday of the summer delivers us fresh jams packed with exciting collaborations and debuts.

This week features releases from big name, genre-crossing collaborations, including Ariana Grande's remix of "the boy is mine" with Brandy and Monica, and Post Malone teaming up with Blake Shelton on their new track "Pour Me a Drink." As you build your new summer playlist, make sure you don't miss out on these ten must-hear tunes.

After a massive year with the release of her EP Like..? and four nominations at the 2024 GRAMMYs, Ice Spice is ready to level up once again with her newest single, "Phat Butt." With self-assured lyricism on top of a classic drill beat that is true to her sound, the track serves as the second single to be released from her debut album, Y2K!. "Phat Butt" comes as both a message to those who lacked belief in Ice Spice’s music career, but also as a quintessential summer anthem.

In the self-directed music video, the rapper is shown performing in front of a wall of graffiti with grainy video filters, emphasizing the Y2K feel. Ice Spice is set to take on her Y2K World Tour next month and it's no doubt that this "Phat Butt" will be a highlight on her setlist.

Explore More: The Rise Of Ice Spice: How The "Barbie World" Rapper Turned Viral Moments Into A Full-On Franchise

Ariana Grande, Brandy, & Monica — "the boy is mine (remix)"

When asking different groups who sings the song "the boy is mine," you're likely to get two answers. Some will say pop star Ariana Grande, while others will think of the original 1998 R&B hit by Brandy and Monica, which won the GRAMMY for Best R&B Performance By A Duo Or Group With Vocal in 1999. Doubling down on the shared name of the track and bridging the generational gap among music lovers, Grande, Brandy, and Monica have come together for a fresh remix of "the boy is mine," and the internet couldn't be more ecstatic.

"My deepest and sincerest thank you to Brandy and Monica, not only for joining me for this moment, but for your generosity, your kindness, and for the countless ways in which you have inspired me," said Grande in an Instagram post announcing the collaboration. "This is in celebration of you both and the impact that you have had on every vocalist, vocal producer, musician, artist that is creating today."

Read More: 5 Takeaways From Ariana Grande's New Album Eternal Sunshine

Post Malone & Blake Shelton — "Pour Me a Drink"

Post Malone has been dipping his toes into the country genre for some time now and fans have been anxiously awaiting his promised western era post Cowboy Carter.

Malone and Shelton first ignited excitement with a sneak peek of their song, "Pour Me a Drink" at the CMA Fest earlier this month. Since Posty announced the official release on Instagram, fans have eagerly awaited its arrival on streaming services. The track serves as a tantalizing preview of Post Malone's upcoming country album, F-1 Trillion, coming August 16.

Read More: Post Malone's Country Roots: 8 Key Moments In Covers and Collaborations

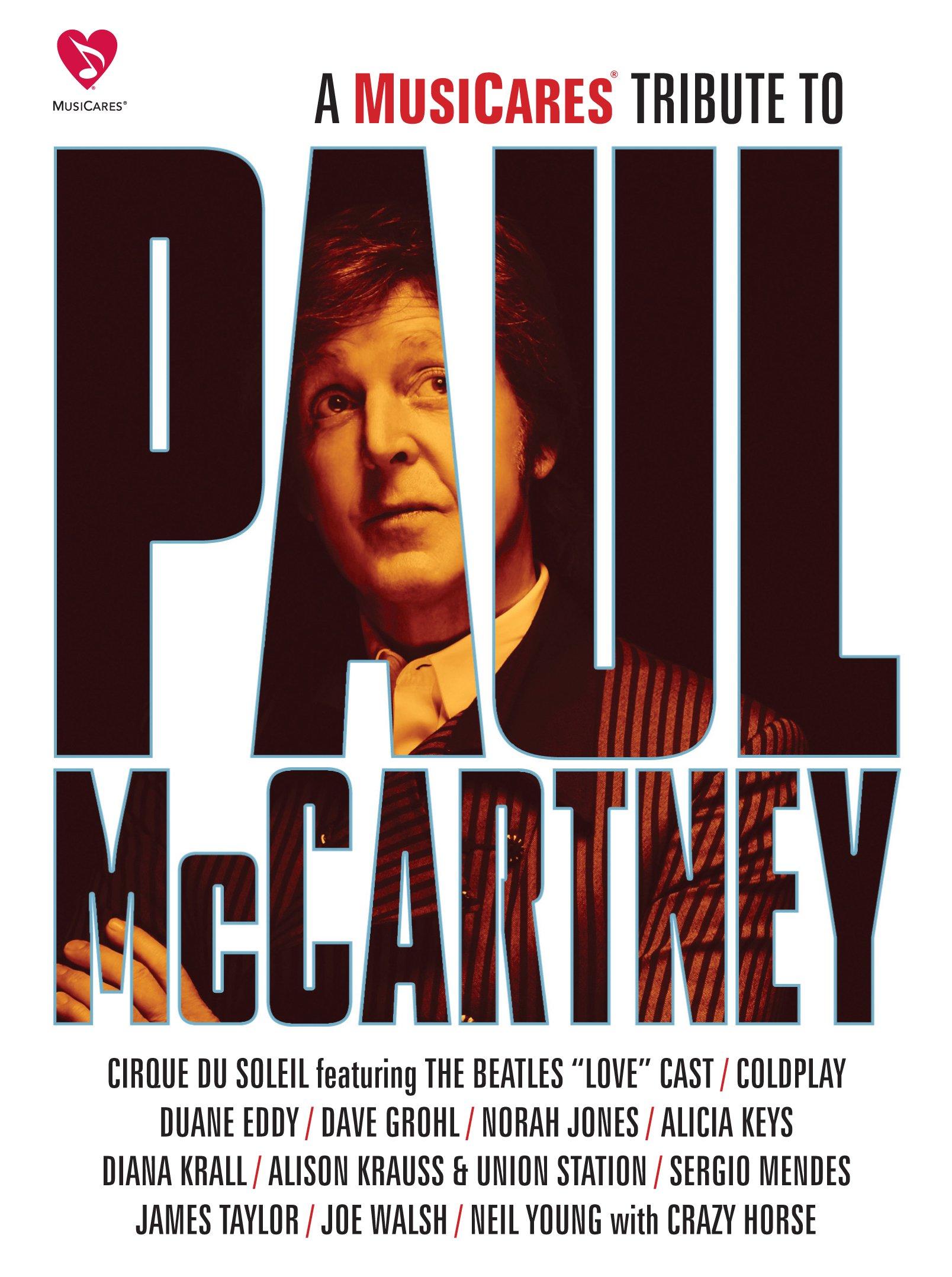

Coldplay — "feelslikeimfallinginlove"

Coldplay has been generating excitement as they embark on their next chapter, with the release of their latest single, "feelslikeimfallinginlove." Over the past few weeks, they've been feeding fans with sneak peeks on social media and performing the song live on their world tour.

The track sets the stage for the release of Coldplay's highly anticipated tenth studio album, Moon Music, set to land in early October. True to their brand, this song is geared to uplift your spirits, making it the perfect anthem for carefree summer car rides with the windows down.

Read More: How Coldplay's Parachutes Ushered In A New Wave Of Mild-Mannered Guitar Bands

Ten years into his career, Norwegian DJ Kygo is dropping his self-titled album, Kygo, which he teased last week with the single "Me Before You" featuring Plested. The song, backed by a thumping mid-tempo instrumental, vividly narrates the transformative experience of being deeply influenced by someone in a relationship and not wanting to return to who you were before. The 18-track project features diverse and vibrant collaborations with unexpected guests like the Jonas Brothers and Ava Max.

Maren Morris & Julia Michaels — "cut!"

Maren Morris and Julia Michaels, GRAMMY-winners both independently renowned for their iconic music collaborations, are now joining forces to release their electrifying new track, "cut!" The duo has been working together for a few years, with Michaels' co-writing Morris' "Circles Around Town," which received a nomination for Best Country Song at the 2023 GRAMMYs. So, while this collaboration might not come as a surprise, it is still certainly a welcomed one.

After a two-year hiatus from releasing music, pop enthusiasts have been eagerly anticipating Morris' return to the spotlight. "Can't wait to cathartically scream f*ck at the top of our lungs together," Morris said in an Instagram post announcing the track.

Learn More: Behind Julia Michaels' Hits: From Working With Britney & Bieber To Writing For Wish

Gracie Abrams — 'The Secret of Us'

Building on the success of her debut album, Good Riddance, and the skyrocketing momentum of her career after opening The Eras Tour, California-native Gracie Abrams has unveiled her much-anticipated sophomore album, The Secret of Us.

The album includes the track, "Close to You," which was released ahead of the album drop as the full realization of a 20-second snippet that Abrams posted on Instagram back in 2018. After sitting on the track for six years and relentless pleas from fans, the pop artist finally delivered the full song — a mesmerizing blend of Abrams’ vocal prowess and heartfelt lyricism.

Learn More: How Making Good Riddance Helped Gracie Abrams Surrender To Change And Lean Into The Present

6LACK — "F**k The Rap Game"

6LACK is rebranding himself and making sure everyone knows. The release of his newest track, "F**k The Rap Game" addresses the phenomenon of getting caught up in the glitz and glamor of the entertainment business, tying in the importance of staying true to one's roots. The Atlanta-raised artist is currently on tour with rapper Russ, with whom he recently released the single "Workin On Me,” another nod to 6LACK's ongoing mission of self-reflection and deep introspection.

“A better me equals a better you equals a better us. That’s been the formula of my life. I can’t thrive unless I’m around people who are constantly trying to better themselves as individuals,” 6LACK said in an interview with GRAMMY.com last year. “It took a second of me really looking at myself in the mirror, being honest and saying: I am not doing as much work on myself as I claim to be doing and want to be doing on myself.”

Read More: 6lack On His Comeback Album SIHAL: "I’m Playing A Different Game"

Months after their buzzworthy performance with Doja Cat at Coachella, South African quintet The Joy has released their self-titled album through Transgressive Records. The album was recorded live, in real time, at Church Studios in London and features no instruments or overdubs — just pure, raw vocals that capture the group's authentic sound.

The Joy came together through a serendipitous twist of fate. Years back, five boys arrived early to their school choir practice and decided to have an impromptu jam session. Realizing their undeniable musical chemistry, The Joy was born, quickly garnering global acclaim. "They are, like, my favorite group," Jennifer Hudson exclaimed on her talk show.

Surfaces — 'good morning'

Known for their feel-good tunes that took over TikTok in 2019, Surfaces presents their sixth album, Good Morning. In tracks like, “Real Estate,” the band chronicles the idea of exploring one’s mind and thoughts, above all other features, backed by a tropical lo-fi instrumental, as well as a steady thump of a bass, and trilling trumpets.

“’Real Estate’ is about the infatuation with that place in someone’s mind that you can’t get enough of,” Surfaces explained in a press statement. “It’s a familiar place to call home that feels safe and deserves all the love in the world. We wanted to capture the bliss of finding that space and reveling in it.”

Lauren Watkins — 'The Heartbroken Record'

Lauren Watkins has a packed summer schedule, which includes opening for country artist Morgan Wallen and releasing her second studio album, The Heartbroken Record. This project draws inspiration from music industry veterans like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, while also infusing influences from contemporary artists like Kacey Musgraves and Miranda Lambert. Each track from the album underscores stories of love and loss, woven together by the overarching theme of heartbreak.

"I didn't want to just put an album out — I wanted it to be purposeful," Watkins said in a press statement. "It's the past several years of my life, and that was just so much heartbreak and dramatic girl-feelings, but I think in a really deep and relatable way… and it just needs to get off my chest."

Why 2024 Is The Year Women In Country Music Will Finally Have Their Moment

.webp)