Bon Jovi have officially been in the cultural conversation for five decades — and it looks like we'll never say goodbye.

The band's self-titled debut album was unleashed upon the world in 1984, and lead single "Runaway" made some waves. Yet the New Jersey group didn't truly break through until their third album, the 12 million-selling Slippery When Wet. By the late 1980s, they were arguably the biggest rock band in the world, selling out massive shows in arenas and stadiums.

Since, Bon Jovi releases have consistently topped album charts (six of their studio albums hit No. 1). A big reason for their continued success is that, unlike a majority of their ‘80s peers, frontman Jon Bon Jovi made sure that they adapted to changing times while retaining the spirit of their music — from the anthemic stomp of 1986’s "Bad Medicine" to the Nashville crossover of 2005’s "Who Says You Can’t Go Home." It also doesn’t hurt that the 2024 MusiCares Person Of The Year has aged very gracefully; his winning smile and charismatic personality ever crush-worthy.

Their fifth decade rocking the planet has been marked by many other milestones: The release of a four-part Hulu documentary, "Thank you, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story"; Bon Jovi's 16th studio album Forever, and fan hopes for the return of original guitarist Richie Sambora who left unexpectedly in 2013.

Despite all of these positive notes, there is an ominous cloud hanging over the group as their singer had to undergo vocal surgery following disappointing, consistently off-key performances on the group's 2022 U.S. tour. Even afterward, he remains unsure whether he’ll be able to tour again. But Bon Jovi remains popular and with Sambora expressing interest in a reunion, it's plausible that we could see them back on stage again somehow.

Jon Bon Jovi has also had quite a multifaceted career spun off of his success in music, as shown by the following collection of fascinating facts.

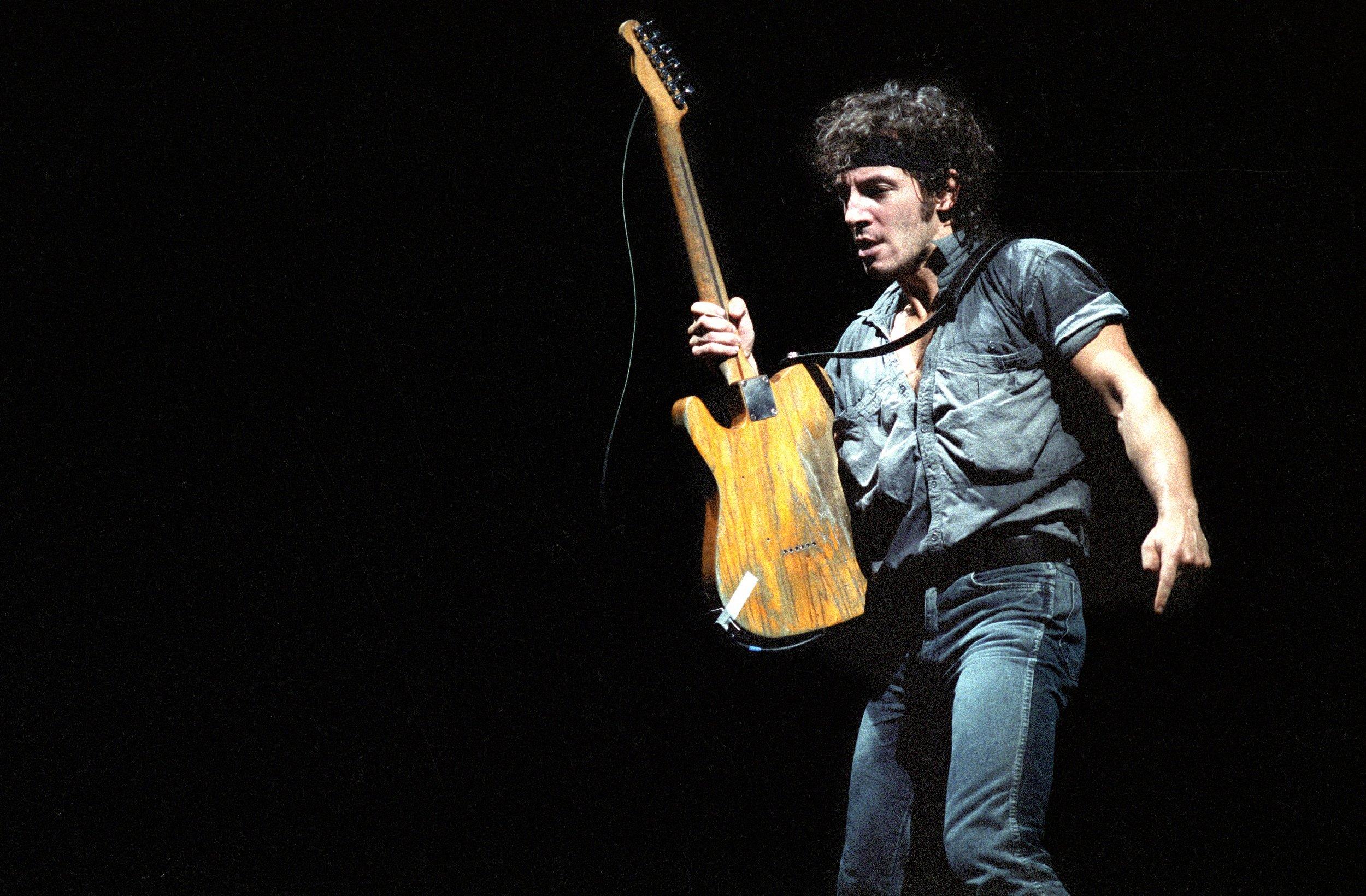

Jon Bon Jovi Sung With Bruce Springsteen When He Was 17

By the time he was in high school, Jon Bongiovi (his original, pre-fame last name) was already fronting his first serious group. The Atlantic City Expressway was a 10-piece with a horn section that performed well-known tunes from Jersey acts like Bruce Springsteen and Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes.

They regularly played The Fast Lane, and one night Bruce Springsteen was in the audience. To Bon Jovi’s surprise, The Boss jumped onstage to join them. The two later became good friends — during his MusiCares performance, Bon Jovi introduced Springsteen as "my mentor, my friend, my brother, my hero."

Jon Recorded Bon Jovi’s First Hit Before The Band Formed

Although "Runaway" was the debut single and lone Top 40 hit from Bon Jovi's first two albums, it was recorded as a professional demo back in 1982.

Bon Jovi got a gig as a gopher at Power Station, the famed studio co-owned by his second cousin Tony Bongiovi where artists like the Rolling Stones, Diana Ross, and David Bowie recorded. (He watched even watched Bowie and Freddie Mercury record the vocals for "Under Pressure.")

The future rockstar cut "Runaway" (which was co-written mainly by George Karak) and other demos with session musicians — his friend, guitarist Aldo Nova, Rick Springfield/John Waite guitarist Tim Pierce, Springsteen keyboardist Roy Bittan, bassist Hugh McDonald (a future Bon Jovi member), and Scandal drummer Frankie LaRocca. The song first appeared on a WAPP compilation under his name, but then it was placed on Bon Jovi’s debut album. When the video for "Runway" was created nearly two years later, members of Bon Jovi were miming to other people’s performances.

Although it is a classic, original guitarist Richie Sambora hates it and never wants to play it again.

He Eloped With His High School Sweetheart In April 1989

During the band’s world tour in support of New Jersey, Bon Jovi and Dorothea Hurley spontaneously eloped in a quickie wedding in Vegas. His bandmates and management were shocked to find this out; the latter probably feared that his ineligible bachelor status would harm their popularity with their ardent female fans. But it simply played more into his more wholesome image that differed from other hard rockers of the time.

In May 2024, Bon Jovi’s son Jake secretly married "Stranger Things" actor Millie Bobby Brown. It was like history repeating itself, except this time family was involved.

Listen: Revisit Jon Bon Jovi's Greatest Hits & Deep Cuts Ahead Of MusiCares' Person Of The Year 2024 Gala

The Bongiovi Family Is Part Of The Bon Jovi Family

Back in the ‘80s, parents often didn’t like their kids’ music. However, Bon Jovi’s parents completely supported his. Mother Carol Bongiovi often chaperoned his early days when he was an underaged kid playing local clubs and bars in New Jersey. Father Jon Sr. was the group’s hair stylist until their third album, Slippery When Wet. He created his son's signature mane.

Jon’s brother Matthew started as a production assistant in the band’s organization, then worked for their management before becoming his brother’s head of security and now his tour manager. His other brother Anthony became the director of a few Bon Jovi concert films and promo clips. He’s also directed concert films for Slayer and the Goo Goo Dolls.

Bon Jovi Is A Regular In Television & Film

After writing songs for the Golden Globe-winning "Young Guns II soundtrack (released as the solo album Blaze Of Glory) and getting a cameo in the Western’s opening, Bon Jovi was bitten by the acting bug. He studied with acclaimed acting coach Harold Guskin in the early ‘90s, then appeared as the romantic interest of Elizabeth Perkins in 1995's Moonlight and Valentino.

In other movies, Bon Jovi played a bartender who’s a recovering alcoholic (Little City), an ex-con turning over a new leaf (Row Your Boat), a failed father figure (Pay It Forward), a suburban dad and pot smoker (Homegrown), and a Navy Lieutenant in WWII (U-571). The band’s revival in 2000 slowed his acting aspirations, but he appeared for 10 episodes of "Ally McBeal," playing her love interest in 2002.

Elsewhere on the silver screen, the singer has also portrayed a vampire hunter (Vampiros: Los Muertos), a duplicitous professor (Cry Wolf), the owner of a women’s hockey team (Pucked), and a rock star willing to cancel a tour for the woman he loves (New Year’s Eve). He hasn’t acted since 2011, but who knows when he might make a guest appearance?

In 2004, Bon Jovi became one of the co-founders and co-majority owner of the Philadelphia Soul, which were part of the Arena Football League (AFL). (Sambora was a minority shareholder.) The team name emerged in a satirical scene from "It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia" during which Danny DeVito’s character tries to buy the team for a paltry sum and twice butchers the singer’s name.

Jon stuck with the team until 2009, a year after they won Arena Bowl XXII, defeating the San Jose SaberCats. He then set his eyes on a bigger prize, the Buffalo Bills, aligning himself with a group of Toronto investors in 2011. One of his biggest competitors? Donald Trump, who ran a smear campaign alleging that the famed singer would move the team to Toronto.

In the end, neither man purchased the team as they were outbid by Terry and Kim Pegula, who still own the Bills today.

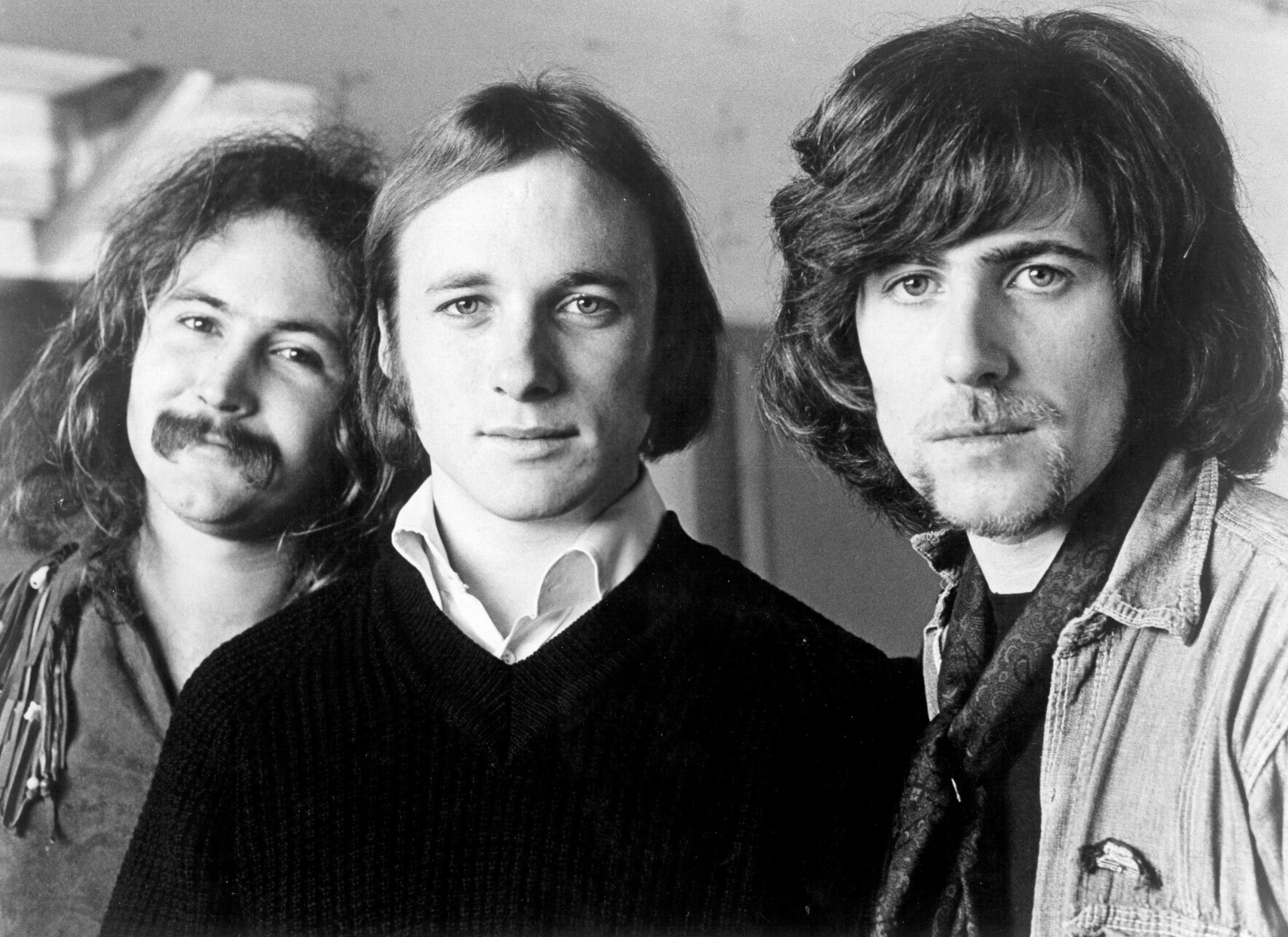

Jon & Richie Sambora Wrote Songs For Other Artists

Having cranked out massive hits with songwriter Desmond Child, Bon Jovi and Sambora decided to write or co-write songs for and with other artists.

In 1987, they co-wrote and produced the Top 20 hit "We All Sleep Alone" with Child for Cher, and also co-wrote the Top 40 hit "Notorious" with members of Loverboy. In 1989, the duo paired up again Loverboy guitarist Paul Dean for his solo rocker "Under The Gun" and bequeathed the New Jersey outtake "Does Anybody Really Fall in Love Anymore?" (co-written with Child and Diane Warren) to Cher.

The Bon Jovi/Sambora song "Peace In Our Time" was recorded by Russian rockers Gorky Park. In 1990, Paul Young snagged the New Jersey leftover "Now and Forever," while the duo penned "If You Were in My Shoes" with Young, though neither song was released. In 2009, Bon Jovi and Sambora were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame for their contributions to music.

Jon Bon Jovi Once Ran His Own Record Label

For a brief time in 1991, he ran his own record label, Jambco, which was distributed through Bon Jovi’s label PolyGram Records. The only two artists he signed were Aldo Nova and Billy Falcon, a veteran singer/songwriter who became Bon Jovi's songwriting partner in the 2000s. Neither of their albums (Aldo Nova’s Blood On The Bricks and Billy Falcon’s Pretty Blue World) were big sellers, and the label folded quickly when they began losing money.

Still, the experience gave Bon Jovi the chance to learn about the music business. That experience helped after he fired original manager Doc McGhee in 1991 and took over his band’s managerial reins until 2015.

Bon Jovi's Vocal Issues Aren't New

Although Jon Bon Jovi's vocal problems have become a major issue recently, they stem back to the late 1980s. It's doubtful as to whether Jon had proper vocal training for a rock band at the start.

The group did 15-month tours to support both the Slippery When Wet and New Jersey albums. Near the end of the grueling Slippery tour, Bon Jovi was getting steroid injections because his voice was suffering.

While his voice held up into the 2000s, it has become apparent over the last decade that his singing is rougher than it used to be. As shown in the Hulu new documentary, the singer has been struggling to maintain his voice. It’s natural for older rock singers to lose some range — it’s been very rare to hear him sing any of the high notes in "Livin’ On A Prayer" over the last 20 years — but he admitshe is unsure whether he can ever tour again, even with recent surgery.

Bon Jovi Has Been A Philanthropist For Over Three Decades

Back in the 1980s, the upbeat Bon Jovi made it clear that they were not going to be a toned-down political band. But in the ‘90s, he and the band toned down their look, evolved their sound, and offered a more mature outlook on life.

Reflecting this evolved viewpoint, the band started an annual tradition of playing a December concert in New Jersey to raise money for various charitable causes; the concert series began in 1991 and continued with the band or Jon solo through at least 2015. The group have played various charitable concert events over the years including the Twin Towers Relief Benefit, Live 8 in Philadelphia, and The Concert For Sandy Relief.

By the late 2000s, Jon and Dorothea founded the JBJ Soul Kitchen to serve meals at lower costs to people who cannot afford them. COVID-19 related food shortages led the couple to found the JBJ Soul Kitchen Food Bank. Their JBJ Soul Foundation supports affordable housing and has rebuilt and refurbished homes through organizations like Project H.O.M.E., Habitat For Humanity, and Rebuilding Together.

While he may be a superstar, Jon Bon Jovi still believes in helping others. For his considerable efforts, he was honored as the 2024 MusiCares Person Of The Year during 2024 GRAMMY Week.

Listen: Revisit Jon Bon Jovi's Greatest Hits & Deep Cuts Ahead Of MusiCares' Person Of The Year 2024 Gala