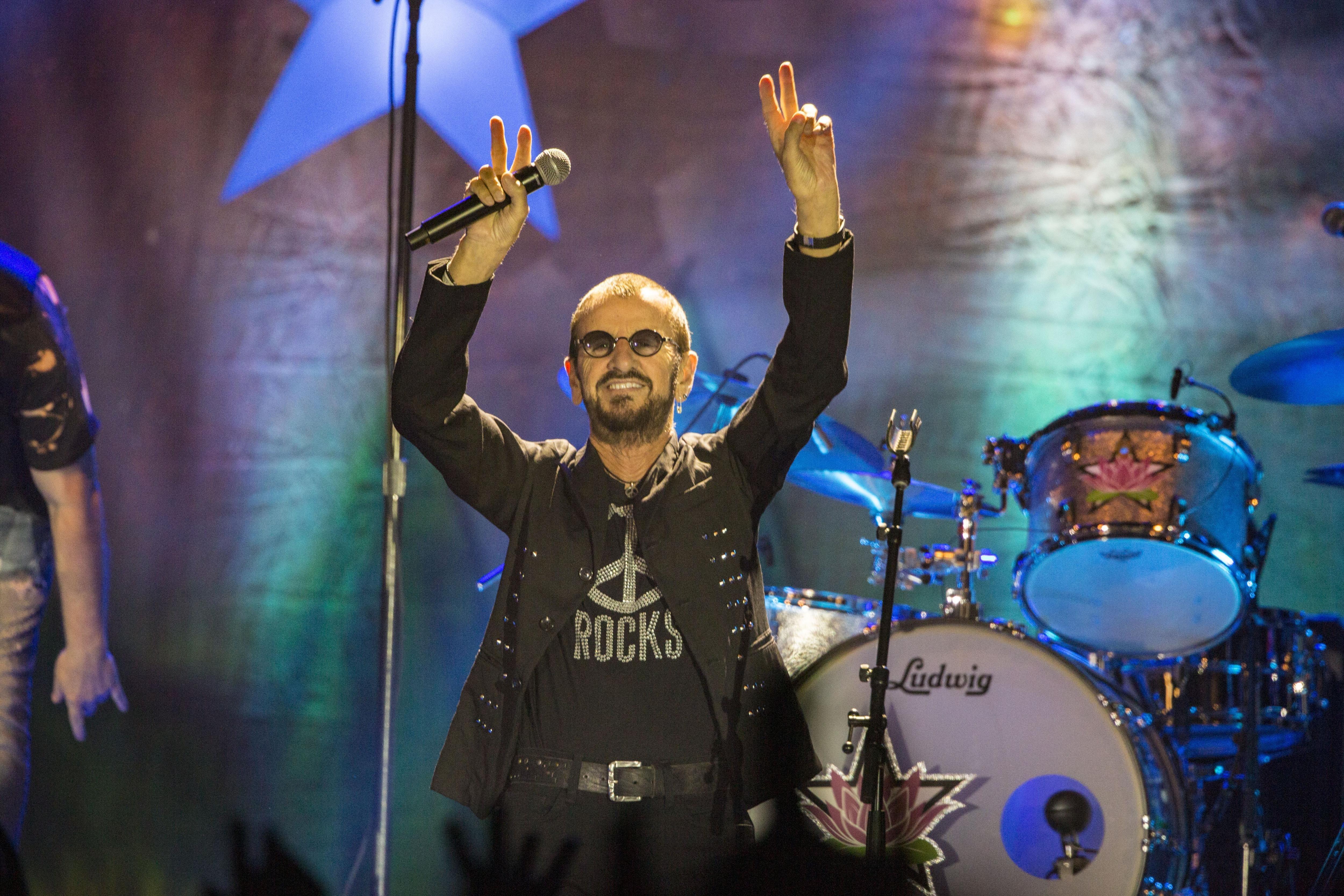

Photo: Daniel Knighton/Getty Images

Ringo Starr

news

Ringo Starr's Peace And Love Birthday Celebrations To Take Place At L.A.'s Capitol Records

Every July 7th (Starr's birthday), fans from more than 20 countries around the world join in on the tradition to "create a wave of Peace & Love across the planet"

Since 2008, GRAMMY-winning Beatles drummer Ringo Starr has celebrated his birthday by asking his fans to come out to the streets at noon to say "peace and love."

Rolling Stone reports that every July 7th (Starr's birthday), fans from more than 20 countries around the world have joined in on the tradition to "create a wave of Peace & Love across the planet." This year, Starr is making the moment even more special by hosting an event at Los Angeles' Capitol Records with performances by Ben Kyle, the Jacks and Sara Watkins.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Ua5EAfAMYpM" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"I’ve said it before but I really can’t think of a better way to celebrate my birthday, or a better gift I could ask for, than peace and love,” Starr said in a statement to the magazine. “It’s so great how every year it keeps growing, with the wave of peace and love starting in the morning on July 7 in Australia and ending in Hawaii, with celebrations in all the time zones in between. I am so happy to be back at Capitol Records, and for our great sponsors who are carrying the message of peace and love around the world, like the David Lynch Foundation, Life is Good, SiriusXM, Modern Drummer and Starbucks. I also want to thank each and everyone of you for continuing to help spread peace and love, Ringo."

Starr's wife Barbara Starkey, Nils Lofgren, former All Starr Band member Sheila E. and more will also make appearances.

Jade Bird Talks Empowering Female Fans & Upcoming Tour With Father John Misty

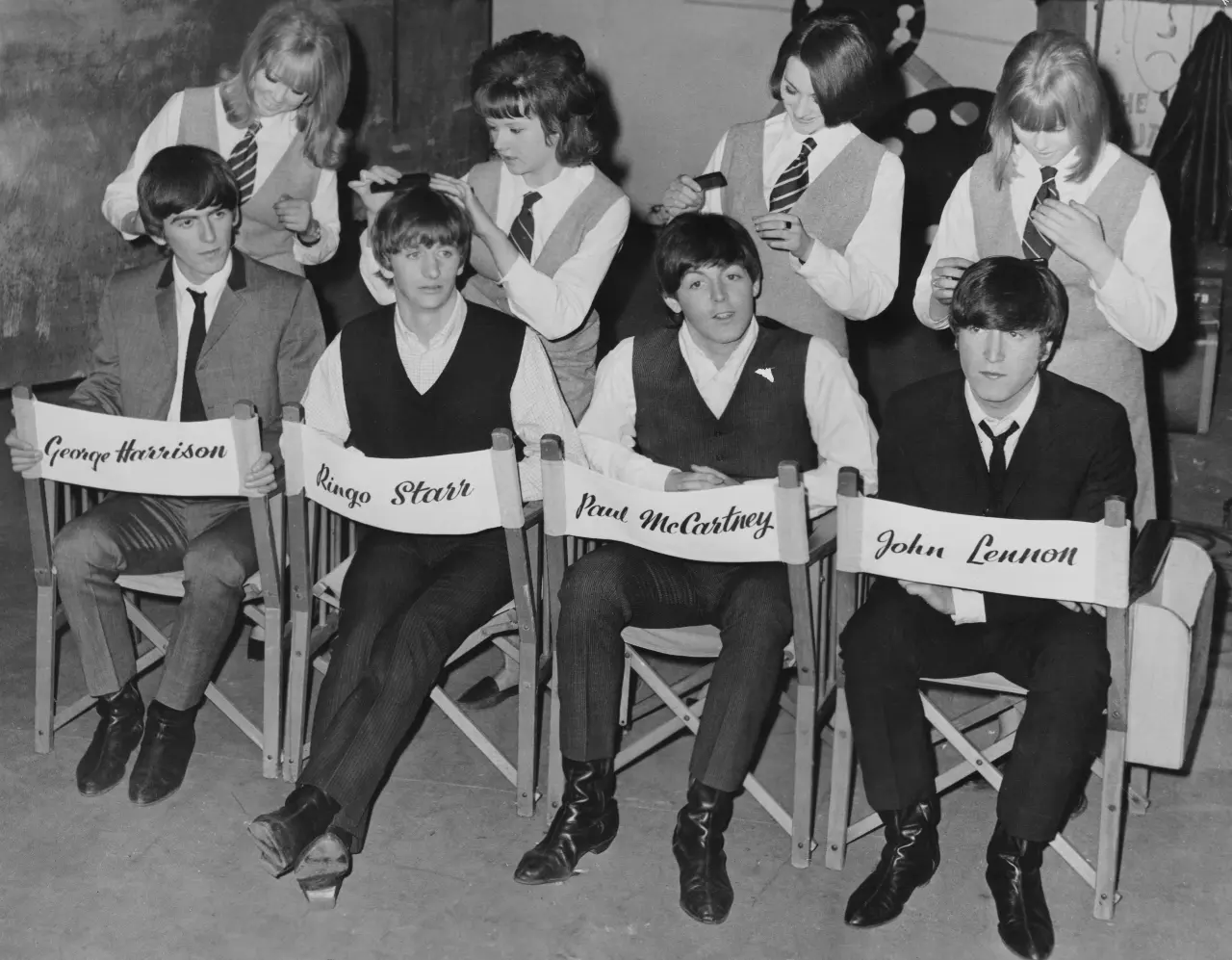

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd

list

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

More than five decades after its 1970 release, Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 'Let it Be' film is restored and re-released on Disney+. With a little help from the director himself, here are some less-trodden tidbits from this much-debated film and its album era.

What is about the Beatles' Let it Be sessions that continues to bedevil diehards?

Even after their aperture was tremendously widened with Get Back — Peter Jackson's three-part, almost eight hour, 2021 doc — something's always been missing. Because it was meant as a corrective to a film that, well, most of us haven't seen in a long time — if at all.

That's Let it Be, the original 1970 documentary on those contested, pivotal, hot-and-cold sessions, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Much of the calcified lore around the Beatles' last stand comes not from the film itself, but what we think is in the film.

Let it Be does contain a couple of emotionally charged moments between maturing Beatles. The most famous one: George Harrison getting snippy with Paul McCartney over a guitar part, which might just be the most blown-out-of-proportion squabble in rock history.

But superfans smelled blood in the water: the film had to be a locus for the Beatles' untimely demise. To which the film's director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, might say: did we see the same movie?

"Looking back from history's vantage point, it seems like everybody drank the bad batch of Kool-Aid," he tells GRAMMY.com. Lindsay-Hogg had just appeared at an NYC screening, and seemed as surprised by it as the fans: "Because the opinion that was first formed about the movie, you could not form on the actual movie we saw the other night."

He's correct. If you saw Get Back, Lindsay-Hogg is the babyfaced, cigar-puffing auteur seen throughout; today, at 84, his original vision has been reclaimed. On May 8, Disney+ unveiled a restored and refreshed version of the Let it Be film — a historical counterweight to Get Back. Temperamentally, though, it's right on the same wavelength, which is bound to surprise some Fabs disciples.

With the benefit of Peter Jackson's sound-polishing magic and Giles Martin's inspired remixes of performances, Let it Be offers a quieter, more muted, more atmospheric take on these sessions. (Think fewer goofy antics, and more tight, lingering shots of four of rock's most evocative faces.)

As you absorb the long-on-ice Let it Be, here are some lesser-known facts about this film, and the era of the Beatles it captures — with a little help from Lindsay-Hogg himself.

The Beatles Were Happy With The Let It Be Film

After Lindsay-Hogg showed the Beatles the final rough cut, he says they all went out to a jovial meal and drinks: "Nice food, collegial, pleasant, witty conversation, nice wine."

Afterward, they went downstairs to a discotheque for nightcaps. "Paul said he thought Let it Be was good. We'd all done a good job," Lindsay-Hogg remembers. "And Ringo and [wife] Maureen were jiving to the music until two in the morning."

"They had a really, really good time," he adds. "And you can see like [in the film], on their faces, their interactions — it was like it always was."

About "That" Fight: Neither Paul Nor George Made A Big Deal

At this point, Beatles fanatics can recite this Harrison-in-a-snit quote to McCartney: "I'll play, you know, whatever you want me to play, or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you… I'll do it." (Yes, that's widely viewed among fans as a tremendous deal.)

If this was such a fissure, why did McCartney and Harrison allow it in the film? After all, they had say in the final cut, like the other Beatles.

"Nothing was going to be in the picture that they didn't want," Lindsay-Hogg asserts. "They never commented on that. They took that exchange as like many other exchanges they'd had over the years… but, of course, since they'd broken up a month before [the film's release], everyone was looking for little bits of sharp metal on the sand to think why they'd broken up."

About Ringo's "Not A Lot Of Joy" Comment…

Recently, Ringo Starr opined that there was "not a lot of joy" in the Let it Be film; Lindsay-Hogg says Starr framed it to him as "no joy."

Of course, that's Starr's prerogative. But it's not quite borne out by what we see — especially that merry scene where he and Harrison work out an early draft of Abbey Road's "Octopus's Garden."

"And Ringo's a combination of so pleased to be working on the song, pleased to be working with his friend, glad for the input," Lindsay-Hogg says. "He's a wonderful guy. I mean, he can think what he wants and I will always have greater affection for him.

"Let's see if he changes his mind by the time he's 100," he added mirthfully.

Lindsay-Hogg Thought It'd Never Be Released Again

"I went through many years of thinking, It's not going to come out," Lindsay-Hogg says. In this regard, he characterizes 25 or 30 years of his life as "solitary confinement," although he was "pushing for it, and educating for it."

"Then, suddenly, the sun comes out" — which may be thanks to Peter Jackson, and renewed interest via Get Back. "And someone opens the cell door, and Let it Be walks out."

Nobody Asked Him What The Sessions Were Like

All four Beatles, and many of their associates, have spoken their piece on Let it Be sessions — and journalists, authors, documentarians, and fans all have their own slant on them.

But what was this time like from Lindsay-Hogg's perspective? Incredibly, nobody ever thought to check. "You asked the one question which no one has asked," he says. "No one."

So, give us the vibe check. Were the Let it Be sessions ever remotely as tense as they've been described, since man landed on the moon? And to that, Lindsay-Hogg's response is a chuckle, and a resounding, "No, no, no."

news

8 Country Crossover Artists You Should Know: Ray Charles, The Beastie Boys, Cyndi Lauper & More

Beyoncé's 'Cowboy Carter' is part of a proud lineage of artists, from Ringo Starr to Tina Turner, who have bravely taken a left turn into country's homespun, heart-on-sleeve aesthetic.

When Beyoncé announced her upcoming album, Cowboy Carter, with the drop of two distinctly country tracks, she broke both genre and barriers. Not only did Queen Bey continue to prove she can do just about anything, but she joined a long tradition of country music crossover albums.

Country music is, like all genres, a construct, designed by marketing companies around the advent of widely-disseminated recorded music, to sell albums. But in the roughly 100 intervening years, genre has dictated much about the who and how of music making.

In the racially segregated America of the 1920s, music was no exception. Marketing companies began to distinguish between "race records" (blues, R&B, and gospel) intended for Black audiences and hillbilly music (country and Western), sold to white listeners. The decision still echoes through music genre stereotypes today.

But Black people have always been a part of country music, a message that's gained recognition in recent years — in part because of advocacy work by those like Rhiannon Giddens, who plays banjo and viola on "Texas Hold 'Em," one of two singles Beyoncé released in advance of Cowboy Carter.

And since rigid genre rules' inception, many artists from Lil Nas X to Bruce Springsteen have periodically dabbled in or even crossed over to country music.

In honor of Beyoncé's foray, here are eight times musicians from other genres tried out country music.

Ray Charles — Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music (1962)

In 1962, the soul music pioneer crossed the genre divide to cut a swingin' two-volume, 14-track revue of country and western music.

Part history lesson and part demonstration of Charles' unparalleled musicianship, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music covers country songs by major country artists of the era, including Hank Williams, Don Gibson, and Eddy Arnold. An instant success, the record topped album sales charts and was Charles' first atop the Billboard Hot 200 charts.

Ringo Starr — Beaucoups of Blues (1970)

The Beatles' drummer loves country music. Ringo Starr cut this album, which sounds like something you'd two-step the night away to at a honky tonk, as his second solo project. He was inspired by pedal steel guitar player and producer Pete Drake, who worked on George Harrison's All Things Must Pass.

With Drake's help, Starr draws out a classic honky tonk sound — pedal steel, country fiddle, and bar room piano — to round out the album.

Beaucoups includes a textbook country heartbreak song, "Fastest Growing Heartache in the West," a bluesy ramblin' man ballad, "$15 Draw," and a surprisingly sweet love song to a sex worker, "Woman Of The Night."

The Pointer Sisters — Fairytale (1974)

Remembered for their R&B hits like "I'm So Excited" and "Jump (For My Love)", the Pointer Sisters dropped "Fairytale," a classic country heartbreak song into the middle of their second studio album, That's A Plenty.

Full of honky tonk pedal steel and fiddle, the track earned the band a GRAMMY award for Country and Western Vocal Performance Group or Duo in 1975, beating out Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Bobby Bare, and the Statler Brothers; they were the first, and to date, only Black women to receive the award.

The same year the song came out, the Pointer Sisters also became the first Black group to play the Grand Ole Opry, arriving to find a group of protesters holding signs with messages like 'Keep country, country!'

Tina Turner — Tina Turns the Country On! (1974)

Also in 1974, Tina Turner cut her first solo album, Tina Turns the Country On!, while she was still performing with then-husband Ike Turner as the Ike & Tina Turner Revue.

Containing the seeds of the powerful, riveting voice she'd fully let loose in her long solo career after separating from her abusive husband, the album presents a stripped down, mellow Turner.

She covers songs like Kris Kristofferson's "Help Me Make It Through The Night" and Bob Dylan's "Tonight I'll Be Staying Here With You," and delivers a soaring rendition of Dolly Parton's "There Will Always Be Music."

Turner was nominated for a GRAMMY award for the album, but in Best R&B Vocal Performance, Female, category.

The Beastie Boys — Country Mike's Greatest Hits (1999)

This Beastie Boys cut only a few hundred copies (most reports say 300) of this spoof country album — reputedly conceived of as a Christmas present for friends and family, and never officially released.

Presenting the supposed greatest hits of a slightly dodgy, enigmatic character – Country Mike, who shares a name with band member "Mike D" Diamond — the album sounds like vintage steel guitar country. Think Hank Williams and Jimmy Rodgers with a dash of musical oddballs Louden Wainwright III and David Allen Coe's humor and funk.

Country Mike appears just briefly in the liner notes of the band's anthology album, The Sounds of Silence, (which also includes two of the album's tracks: "Railroad Blues" and "Country Mike's Theme"), as part of an alternate universe wherein Mike temporarily lost his memory when he was hit on the head.

"The psychologists told us that if we didn't play along with Mike's fantasy, he could be in grave danger," the notes read. "This song ('Railroad Blues') is one of the many that we made during that tragic period of time."

Cyndi Lauper — Detour (2016)

The "Girls Just Want To Have Fun" singer enjoyed herself thoroughly by deviating from her typical style with 2016's Detour.

Road tripping into country music land, Lauper covered country songs of the 1950s and 1960s, including Marty Robbins' "Begging You," Patsy Montana's "I Want to be a Cowboy's Sweetheart" and Dolly Parton's "Hard Candy Christmas" with guest appearances by Willie Nelson, Alison Krauss, Emmylou Harris, and Vince Gill.

Jaret Ray Reddick — Just Woke Up (2022)

It might be hard to imagine the Bowling for Soup frontman, known for teenage pop-punk angst hits like "Girl all the Bad Guys Want" and "Punk Rock 101" crooning country ballads.

But in 2022, under the name Jaret Ray Reddick, he cut his solo debut, Just Woke Up. Drawing inspiration from Reddick's native Texas, the steel guitar and twang driven album features duets with Uncle Cracker, Cody Canada, Frank Turner, and Stephen Egerton.

Self-effacing and personable as ever, Reddick heads off questions about the viability of his country music with the album's first track, "Way More Country," acknowledging the questions listeners might have:

"I sing in a punk rock band/ And I know every word to that Eminem song "Stan"/ And I've got about a hundred and ten tattoos / But I'm way more country than you."

Bing Crosby — "Pistol Packin' Mama" (Single, 1943)

Legendary crooner of classic Christmas Carols and American standards, Bing Crosby decided to try his hand at country music with his cover of Al Dexter's "Pistol Packin' Mama," the first country song to appear on Billboard's charts.

The song, which tells the story of a man begging his woman not to shoot him when she discovers him out on the town fooling around, has since also been covered by Willie Nelson, Hoyt Axton, and John Prine.

How Beyoncé Is Honoring Black Music History With "Texas Hold Em," 'Renaissance' & More

Photo: Mark and Colleen Hayward / Redferns / Getty Images

news

'Meet The Beatles!' Turns 60: Inside The Album That Launched Beatlemania In America

A month before the Beatles played "The Ed Sullivan Show," they released their second American studio album — the one most people heard first. Here's a track-by-track breakdown of this magnitudinous slab of wax by the Fab Four.

For many in America, Meet the Beatles! marked their first introduction to the legendary Fab Four — and their lives would be forever altered.

Released on Jan. 20, 1964 by Capitol Records, the Beatles' second American studio album topped the Billboard 200 within a month and stayed there for 11 weeks — only to be ousted by their next U.S. album release, The Beatles' Second Album.

It's almost impossible to put into words the impact of Meet the Beatles! on an entire generation of the listening public. But Billy Corgan, of the Smashing Pumpkins, gave it a shot as an early fan of the Beatles in a series of LiveJournal remembrances — in this case, of himself at five years old, in 1972.

"I am totally overwhelmed by the collective sound of the greatest band ever blasting in mono thru a tin needle into a tiny speaker," he wrote. "I associate this sound forever with electricity, for it sends bolts thru my body and leaves me breathless. I can not stand still as I listen, so I must spin… I spin until I am ready to pass out, and then I spin some more."

So many other artists remember that eureka moment. "They were doing things nobody was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid," Bob Dylan said of the opening track, "I Want to Hold Your Hand." "I knew they were pointing the direction of where music had to go." Everyone from Ozzy Osbourne to Sting and Questlove agreed.

From Meet the Beatles!, the Fabs would have the most astonishing five-or-six-year run in music. And so much of their songwriting and production innovation can be found within its grooves; truly, the world had no idea what it was in for. In celebration of the 60th anniversary of Meet the Beatles!, here's a quick track-by-track breakdown.

"I Want to Hold Your Hand"

The Fabs' first American No. 1 hit may have been about the chastest of romantic gestures. Still, there's nothing heavier than "I Want to Hold Your Hand," because it's clamor and fraternity. That seemingly saccharine package also contained everything they'd ever do in concentrate — hints of the foreboding of "Ticket to Ride," the galactic final chord of "A Day in the Life," and beyond.

"I Saw Her Standing There"

A few too many awards show tributes have threatened to do in "I Saw Her Standing There," but they've failed. As the opening shot of their first UK album, Please Please Me, it's perfect, but as the second track on Meet the Beatles!, it just adds to the magnitude. What a one-two punch.

"This Boy"

Songwriting-wise, "This Boy" drags a little; it becomes a little hazy who "this boy" or "that boy" are. But it's not only a killer Smokey Robinson rip; John Lennon's double-tracked vocal solo still punches straight through your chest. (Where applicable, go for the 2020s Giles Martin remix, which carries maximum clarity, definition and punch — said solo is incredible in this context.)

"It Won't Be Long"

Half a dozen other songs here have overshadowed "It Won't Be Long," but it's still one of the early Beatles' most ruthless kamikaze missions, an assault of flying "yeahs" that knocks you sideways.

"All I've Got to Do"

Lennon shrugged off "All I've Got to Do" as "trying to do Smokey Robinson again," and that's more or less what it is. One interesting detail is the conceit of calling a girlfriend on the phone, which was firmly alien to British youth: "I have never called a girl on the 'phone in my life!"he said later in an interview. "Because 'phones weren't part of the English child's life."

"All My Loving"

"All My Loving" was the first song the Beatles played on the American airwaves: when Lennon was pronounced dead, eyewitnesses attest the song came over the speakers. It's a grim trajectory for this most inventive and charismatic of early Beatles singles, with Lennon's tumbling rhythm guitar spilling the composition forth. (About that unorthodox strumming pattern: it seems easy until you try it. And Lennon did it effortlessly.)

"Don't Bother Me"

As Dreaming the Beatles author Rob Sheffield put it, "'Don't Bother Me,' his first real song, began the 'George is in a bad mood' phase of his songwriting, which never ended." Harrison wouldn't pick up the sitar for another year or two, but the song still carries a vaguely dreamy, exotic air.

"Little Child"

"I'm so sad and lonely/ Baby, take a chance with me." For a tortured, creative kid like Corgan, from a rough background — and, likely, a million similar young folks — Lennon's childlike plea must have sounded like salvation.

"Till There Was You"

McCartney's infatuation with the postwar sounds of his youth never ended, and it arguably began on record with this Music Man tune. As usual, McCartney dances right on the edge of overly chipper and apple-cheeked. But here, George Martin's immersive, soft-focused arrangement makes it all work.

"Hold Me Tight"

Like "Little Child," "Hold Me Tight" is a tad Fabs-by-numbers, showing how they occasionally painted themselves into a corner as per their formula. Their rapid evolution from here would leave trifles like "Hold Me Tight" in the rearview.

"I Wanna Be Your Man"

Tellingly, Lennon and McCartney tossed this half-written composition to the Stones — and to Ringo Starr. Mick Jagger's typically lusty performance works, but Starr's is even better — the funny-nosed drummer throws his whole chest into this vocal workout.

"Not A Second Time"

Meet the Beatles! concludes with this likable Lennon tune about heartbreak — maybe C-tier by his standards, but it slouches toward his evolutionary step that would be A Hard Day's Night.

Soon, these puppy-dog emotions ("And now you've changed your mind/ I see no reason to change mine/ I cry") would curdle and ferment in astonishing ways — in "Ticket to Ride," in "Girl," in "Strawberry Fields Forever." And it all began with Meet the Beatles! — a shot heard around the world.

1962 Was The Final Year We Didn't Know The Beatles. What Kind Of World Did They Land In?