Photos: Kate Simon

interview

Photographer Kate Simon Details Her Time With Reggae's Greats & How Bob Marley Was "Completely Possessed By The Music"

'Rebel Music: Bob Marley & Roots Reggae,' a long out-of-print photobook detailing the performances and creative impulses of Bob Marley and other reggae giants was rereleased on Nov. 7. Photographer Kate Simon shares stories behind several of her images.

In the 1970s, Kate Simon was an American rock photographer living in London, living what must have been an incredibly glamorous — or at least incredibly cool — life. She shot the titans of UK rock, working with everyone from Rod Stewart and Queen, to Led Zeppelin and the Who.

With such a resume, one might assume that Simon would be hard to impress. But that was far from the reality — Simon was awestruck by Bob Marley and the Wailers' performance at London's Lyceum theater in 1975.

"That's when I was really blown away by reggae. That was the beginning," Simon recalls. The show was also the beginning of a photographic relationship with reggae music; Simon photographed Marley and other reggae luminaries on stage and behind the scenes until 1980. Among her many works is the cover for Marley's 1978 record, Kaya.

Simons' significant archive is featured in the photobook Rebel Music: Bob Marley & Roots Reggae. Originally published in 2004 in a limited run of 500 copies, Rebel Music Simon's photos and stories from 24 contributors, including Chris Blackwell, Lenny Kravitz, Keith Richards, Paul Simon, Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen. A new edition via Genesis Publications, which is available Nov. 7 in a larger run, includes additional never-before-seen photos and additional stories.

"Look at these pictures of these guys — forget that I took them — that was such an amazing time for music," Simon reflects. "How mystical and beyond belief was this music? It was just so special."

In celebration of the release, Simon spoke with GRAMMY.com about several of the crucial images from Rebel Music: Bob Marley & Roots Reggae. Read on for eight things Simon shared about photographing Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, Lee "Scratch" Perry, Peter Tosh and others.

All images copyright Kate Simon

Bob Marley Was A Particularly Humble Superstar

Kate Simon first met Marley in 1975, backstage at his now-infamous string of shows at the Lyceum Theater in London; her friend Aninha Capaldi was married to a member of the band Traffic, who was friends with Chris Blackwell of Island Records.

"We had an instant kind of rapport," Simon recalls. "Bob was completely charming, and just delightful. Just friendly, just lovely. Really willing to be photographed."

Marley also had a different personality than many of his contemporaries. Simon describes him as a down-to-earth, humble musician whose personality on and off stage lacked any traditional rock star quality. Marley wore the same denim long-sleeved shirt, jeans and jacket for the entire European tour, she recalls, and never had "minders" as some other acts might have.

"He didn't have anybody surrounding him and distancing him from other people. He was very self reliant and very bold," Simon reflects. "I think he was very present and very self aware…reflective and intelligent."

The Lyceum Shows Were A "Watershed Moment" For Reggae

Although Marley and the Wailers had broken through to the international market with 1973's Catch A Fire, his 1975 run of shows — and, particularly, the two gigs at the Lyceum Theatre in July — were a "watershed moment" for the band and reggae as a whole, Simon asserts.

The Wailers' booker had a policy of booking the group at venues much too small for their growing following, Rebel Music details, and there were regularly hundreds of fans who were unable to get inside. In the book, reggae documentarian Roger Steffens describes the vibe outside of the Lyceum shows as "bedlam" and 1975 as "the year that [Marley] became an international star."

Those who were lucky enough to get inside the Lyceum were packed tight to watch Marley, drummer Carlton Barrett, bassist "Family Man" Barrett, guitarist Al Anderson, and backing vocalists the I-Threes. "The band was so tight, and they were ready and there was such an enthusiastic crowd," Simon recalls.

Simon further described the performance in Rebel Music: "It was shocking. The beauty of his voice; the brilliance of his band; the hypnotic power of the music. For me, it was a calling to reggae. I wasn't prepared for it."

The two Lyceum shows became a live album, Live!, released on Island Records that same year.

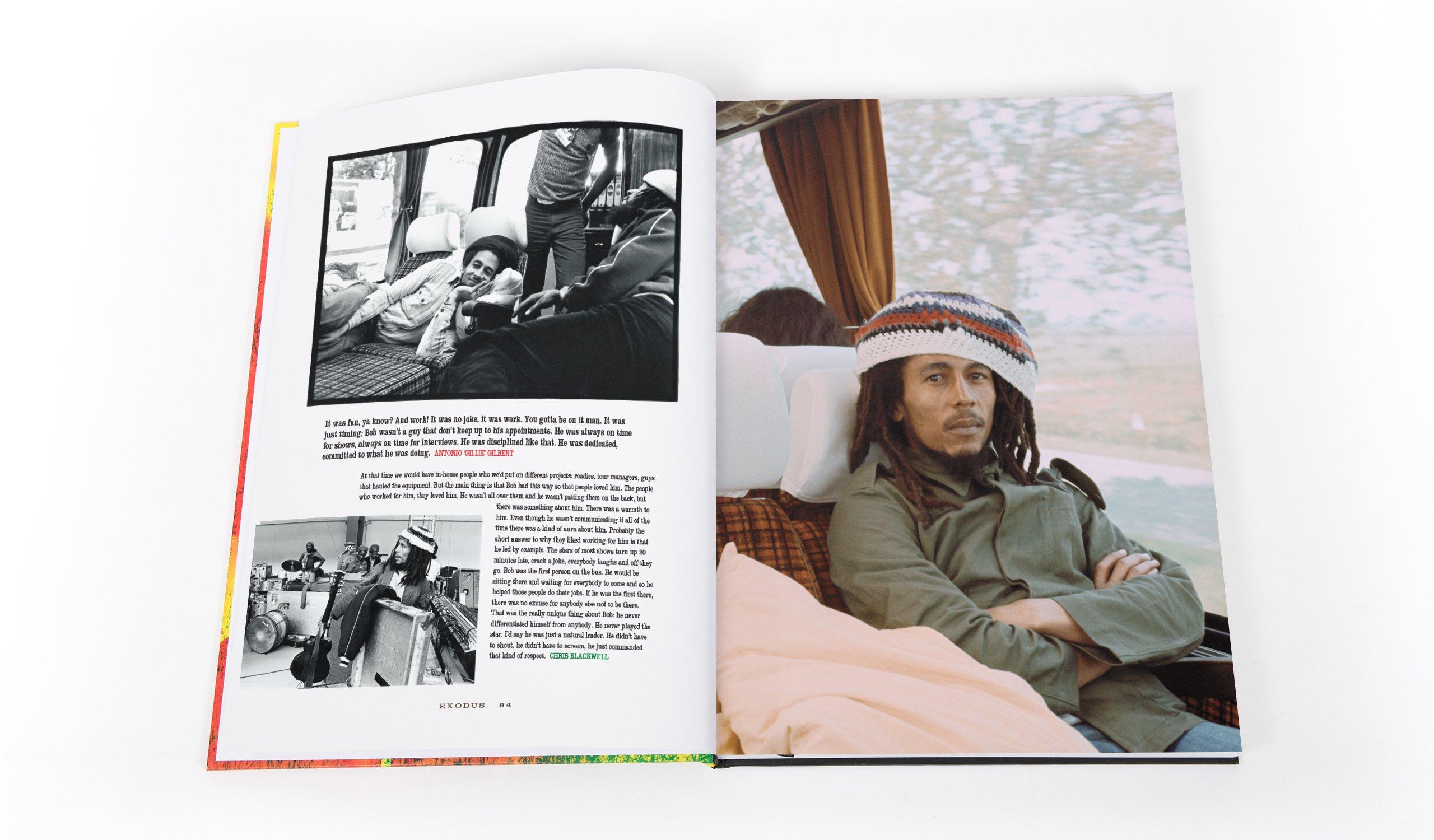

Bob Marley Was A Great Photo Subject — But He Took Coaching

Taken during the Exodus tour in 1977, the above photo has never been published before. Simons explains that Marley was a great photo subject, though shooting him during performances could be difficult because "he never stops running" around on stage. Still, that movement helped her capture "whirling dread shots."

While Marley was keen to be photographed live and offstage, Simon did offer some advice:

"He was completely possessed by the music. I just remember telling him 'Bob, you gotta open your eyes more, because your eyes are always closed.' He's meditating in the music," she says with a laugh. "I could be being egoistic, but I noticed him opening his eyes a little bit more, especially when he sang the phrase 'open your eyes and look within.'"

Bob Marley Was Part Of The "Mount Rushmore Of Reggae"

Although they weren't with Marley during his 1975 tour, the original Wailers — Marley, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh — had been performing together since 1963. Recently an independent nation, ska was the freedom sound of Jamaican music at the time and the trio first topped the charts singing "Simmer Down" with legendary group the Skatalites.

Although their sound would change significantly over the years both as a group and as solo acts, Tosh, Wailer and Marley remained titans in the field — "the Mount Rushmore of reggae music," as Simon suggests, "the three major songwriters and singers of the original Wailers."

Bunny Wailer would go on to win three GRAMMY Awards, one for Best Reggae Recording (Time Will Tell - A Tribute To Bob Marley) and two for Best Reggae Album (Crucial! Roots Classics, Hall Of Fame - A Tribute To Bob Marley's 50th Anniversary). Tosh took home a golden gramophone at the 1998 GRAMMYs for his song "No Nuclear War."

Bunny Wailer Was Less Amenable To Photographers

Simon and a few journalists had traveled to Jamaica to interview Bunny Wailer on the occasion of his new record, 1976’s Blackheart Man, which featured reggae classics like "Dreamland" and many of the best musicians in Jamaica.

"Bunny Wailer was really revered on the island and in regard to roots rock reggae music," Simon notes. "He has one of the most beautiful singing voices I've ever heard. I think he's a great songwriter."

Yet speaking to the man was no easy task. Wailer made the group wait for about seven days before arriving at producer and singer Tommy Cowan's house in Kingston.

"[Bunny] took his time, but when he showed up, I got two and a half of the best rolls of film I ever shot in black and white, and then I got a better roll in color," Simon says.

Peter Tosh Could Control The Weather…At Least One Time

Simon interviewed Tosh in Kingston in 1976, around the time of the release of his song "Legalize It."

"I had been told that Peter had this kind of serious vibe," Simon recalls of the session. "He had this beautiful speaking voice, and he's wearing that ‘Legalize it’ pin on his hat. He was doing all these karate moves. He was really a great photo subject."

In the middle of the shoot, lightning struck. "And he said, 'Jah Rasfafari. You hear that? I made that happen.' I was like, 'uh-huh, ok.' Who am I to know? That was kind of like this entrée to Jamaicanisms that I was going to hear the whole time I was down there."

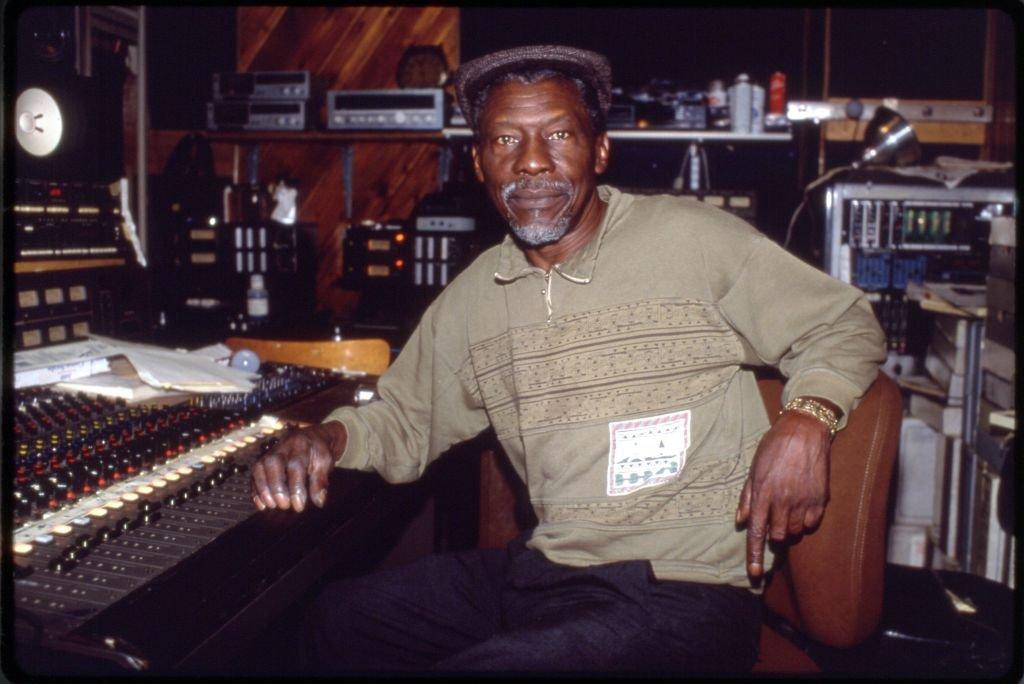

Lee "Scratch" Perry Was A Major Influence On Reggae, And Bob Marley In Particular

Behind the scenes, GRAMMY-winning producer Lee "Scratch" Perry was shaping the sound of reggae music. From his home studio in Kingston, the Black Ark, Perry invented dub music — a forebearer of all modern electronic music that utilizes the mixing board as an instrument. Recalls Simon: "Everybody went to [Perry's] studio, and he was really a genius. I loved photographing him."

Perry worked with Marley, Bunny and Tosh, Sly & Robbie, and many other notable artists. "He really had such an impact on everybody doing music at the time," Simon adds. "He sort of got a reputation for being kind of eccentric, but I saw it; he was really brilliant. How he influenced Bob Marley was really significant. I've read that [Scratch] helped Bob in the beginning, and that Bob lived in his studio or something like that. He certainly helped the early Wailers; he produced some of their earliest tracks."

When Simon took the above photograph, the producer was working with the Heptones and the Congos. Eventually, Perry made Simon's photo into a painted mural on the side of the Black Ark.

Bob Marley's Success Wasn't Expected, But It's Unsurprising

By the time Marley and the Wailers were on their Exodus tour in 1977 (Simon was the photographer during the tour's European leg), the group had already released Exodus, Catch A Fire, Burnin', Rastaman Vibration, Natty Dread — all by the time he was 32 years old.

"That's an astounding amount of art," Simon says.

As a Rastafarian, Bob Marley operated with a set of spiritual beliefs that also permeated his music; Simon found his perspective and attitude appealing. "It really is similar to the perspective that I like to work with and live by," she says. "I think that Bob's music was about interdependence. 'When the rain fall/ it don't fall on one man's house.'"

The global impact of Marley's music and message — as well as the long-lasting popularity of reggae music as a whole — was far from foretold. "But am I surprised? Not even slightly," Simon reflects. "Over 40 years later, why do I want to put a book out about Bob? Why do I listen to Bob Marley if I had my choice, more than anyone else? There's something about this music that is eternal.

"And I think the only one who knew that was Bob," Simon adds, referencing a 1979 interview where Marley described wealth as "life forever." Indeed, the music of Bob Marley and his contemporaries is timeless and a high watermark in reggae music.

"You go around the world [and see images of] Bob Marley, John Lennon and Che Guevara," Simon says. "I think that Bob will continue to be, you know, loved and be an inspiration most importantly, and he'll I think he'll, he'll get bigger and bigger. He's forever."

Living Legends: Burning Spear On New Album, 'No Destroyer' & Taking Control Of His Music

Photo: David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Regarded as Jamaica’s Motown, Coxsone Dodd's Studio One helped launch the careers of legends such as Burning Spear, Toots and the Maytals, and the Wailers. In honor of the 20th anniversary of Dodd’s passing, learn about 10 of his greatest productions.

On April 30, 2004, producer Clement Seymour "Sir Coxsone" Dodd — an architect in the construction of Jamaica’s recording industry — was honored at a festive street renaming ceremony on Brentford Road in Kingston, Jamaica. The bustling, commercial thoroughfare at the geographical center of Kingston was rechristened Studio One Blvd. in recognition of Coxsone’s recording studio and record label.

Dodd is said to have acquired a former nightclub at 13 Brentford Road in 1962; his father, a construction worker, helped him transform the building into the landmark studio. In 1963 Dodd installed a one-track board and began recording and issuing records on the Studio One label.

Dodd’s Studio One was Jamaica’s first Black-owned recording facility and is regarded as Jamaica’s Motown because of its consistent output of hit records. Studio One releases helped launch the careers of numerous ska, rocksteady and reggae legends including Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, the Gladiators, the Skatalites, Toots and the Maytals, Marcia Griffiths, Sugar Minott, Delroy Wilson and most notably, the Wailers.

At the street renaming ceremony, a jazz band played, speeches were given in tribute to Dodd’s immeasurable contributions to Jamaican music and many heartfelt memories from the studio’s heyday were shared. In the culmination of the late afternoon program, Dodd, his wife Norma, and Kingston’s then mayor Desmond McKenzie unveiled the first sign bearing the name Studio One Blvd. Four days later, on April 4, 2002, Coxsone Dodd suffered a fatal heart attack at Studio One. His productions, however, live on as benchmarks within the island’s voluminous and influential music canon.

Born Clement Seymour Dodd on Jan. 26, 1932, he was given the nickname Sir Coxsone after the star British cricketer whose batting skills Clement was said to match. As a teenager, Dodd developed a fondness for jazz and bebop that he heard beamed into Jamaica from stations in Miami and Nashville and the big band dances he attended in Kingston. Dodd launched Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system around 1952 with the impressive collection of R&B and jazz discs he amassed while living in the U.S., working as a seasonal farm laborer.

Many sound system proprietors traveled to the U.S. to purchase R&B records — the preferred music among their dance patrons and key to a sound system’s following and trumping an opponent in a sound clash. With the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, suitable R&B records became scarce. Jamaica’s ever-resourceful sound men ventured into Kingston studios to produce R&B shuffle recordings for sound system play.

Recognizing there was a wider market for this music, Dodd pressed up a few hundred copies of two sound system favorites for general release, the instrumental "Shuffling Jug" by bassist Cluett Johnson and his Blues Blasters and singer/pianist Theophilus Beckford’s "Easy Snapping," both issued on Dodd’s first label, Worldisc. (Some historians recognize "Easy Snapping" as a bridge between R&B shuffle and the island’s Indigenous ska beat; others cite it as the first ska record.) When those discs sold out within a few days, other soundmen followed Dodd’s lead and Jamaica’s commercial recording industry began to flourish.

"Before then, the only stuff released commercially were mento records that were recorded here, but our sound really hit so we kept on recording. When I heard 'Easy Snapping,' I said 'Oh my gosh!'" Coxsone recalled in a 2002 interview for Air Jamaica's Skywritings at Kiingston’s Studio One. "I thank God for that moment."

Dodd was the first producer to enlist a house band, pay them a weekly salary rather than per record. Together, they had an impressive run of hits in the ska era in the early ‘60s; during the rocksteady period later in the decade, Dodd ceded top ranking status to long standing sound system rival (but close family friend) turned producer Duke Reid. (Still, Studio One released the most enduring instrumentals or rhythm tracks, also known as riddims, of the period.) As rocksteady morphed into reggae circa 1968, Dodd triumphed again with consistent releases of exceptional quality.

In 1979 armed robbers targeted the Brentford Rd premises several times. Dodd left Jamaica and established Coxsone’s Music City record store/recording studio in Brooklyn, dividing his time between New York and Kingston. Reissues of Dodd’s music via Cambridge, MA based Heartbeat Records, beginning in the mid 1980s, followed by London’s Soul Jazz label in the 2000s, and most recently Yep Roc Records in Hillsborough, NC, have helped introduce Studio One’s masterful work to new generations of fans.

"The best time I’ve ever had was when I acquired my studio at 13 Brentford Rd. because you can do as many takes until we figured that was it," Coxsone reflected in the 2002 interview. "God gave me a gift of having the musicians inside the studio to put the songs together. In the studio, I always thought about the fans, making the music more pleasing for listening or dancing. What really helped me was having the sound system, you play a record, and you weren’t guessing what you were doing, you saw what you were doing."

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Coxsone Dodd’s passing, read on for a list of 10 of his greatest productions.

The Maytals - "Six and Seven Books of Moses" (1963)

In 1961 at the dawn of Jamaica’s ska era, Toots Hibbert met singers Nathaniel "Jerry" Matthias and Henry "Raleigh" Gordon and they formed the Maytals. The trio released several hits for Dodd including the rousing, "Six and Seven Books of Moses," a gospel-drenched ska track that’s essentially a shout out of a few Old Testament chapters.

Moses is credited with writing five chapters, as the lyrics state, "Genesis and Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers Deuteronomy," but "the Six and Seven books" are in question. Many Biblical scholars say Moses wasn’t the scribe, believing those chapters, including phony spells and incantations to keep evil spirits away, were penned in the 18th or 19th century.

Nevertheless, there’s a real magic formula in The Maytals’ "Six and Seven Books of Moses": Toots’ electrifying preacher at the pulpit delivery melds with elements of vintage soul, gritty R&B, and classic country; Jerry and Raleigh provide exuberant backing vocals and seminal ska outfit and Studio One’s first house band, the Skatalities deliver an irresistible, jaunty ska rhythm with a sophisticated jazz underpinning.

The Wailers - "Simmer Down" (1964)

A flashback scene in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love depicts the Wailers (then a teenaged outfit called the Juveniles) approaching Dodd for a recording opportunity; Dodd inexplicably points a gun at them as they recoil in terror. Yet, there isn’t any mention of such an inappropriate and unprovoked action from the producer in the various books, documentaries, interviews and other accounts of the Wailers’ audition for Dodd.

The Wailers’ first recording session with Dodd in July 1964, however, yielded the group’s first hit single "Simmer Down." At that time, the Wailers lineup consisted of founding members Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston (later Wailer) and Peter Tosh alongside singers Junior Braithwaite and (the sole surviving member) Beverley Kelso. When Junior left for the U.S., Dodd appointed Marley as the group’s lead singer.

The energetic "Simmer Down" cautions the impetuous rude boys to refrain from their hooligan exploits. The Skatalites’ spirited horn led intro, thumping jazz infused bass and fluttering sax solo, enhances Marley’s youthful lead and the backing vocalists’ effervescence. The Wailers would spend two years at Studio One and record over 100 songs there, including the first recording of "One Love" in 1965; by early 1966, they would have five songs produced by Dodd in the Jamaica Top 10.

Alton Ellis -"I’m Still In Love" (1967)

Jamaica’s brief rocksteady lasted about two years between 1966-1968, but was an exceptionally rich and influential musical era. The rocksteady tempo maintained the accentuated offbeat of its ska predecessor, but its slower pace allowed vocal and musical arrangements, affixed in heavier, more melodic basslines.

Alton Ellis is considered the godfather of rocksteady because he had numerous hits during the era and released "Rock Steady," the first single to utilize the term for producer Duke Reid. Ellis initially worked with Dodd in the late 1950s then returned to him in 1967. The evergreen "I’m Still in Love" was penned by Alton as a plea to his wife as their marriage dissolved: "You don’t know how to love me, or even how to kiss me/I don’t know why." Supporting Alton’s elegant, soulful rendering of heartbreak, Studio One house band the Soul Vendors, led by keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, provide an engaging horn-drenched rhythm, epitomizing what was so special about this short-lived time in Jamaican music.

"I’m Still In Love" has been covered by various artists including Sean Paul and Sasha, whose rendition reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2004. Beyoncé utilized Jamaican singer Marcia’s Aitken’s 1978 version of the tune in a TV ad announcing her 2018 On The Run II tour with Jay-Z. In February 2024, Jennifer Lopez sampled "I’m Still in Love" for her single "Can’t Get Enough."

Bob Andy - "I’ve Got to Go Back Home" (1967)

The late Keith Anderson, known professionally as Bob Andy, arrived at Studio One in 1967. He quickly became a hit-making vocalist, and an invaluable writer for other artists on the label. He penned several hits for Marcia Griffiths including "Feel Like Jumping," "Melody Life" and "Always Together," the latter their first of many hit recordings as a duo.

A founding member of the vocal trio the Paragons, "I’ve Got to go Back Home" was Andy’s first solo hit and it features sublime backing vocals by the Wailers (Bunny, Peter and Constantine "Vision" Walker; Bob Marley was living in the USA at the time.) Set to a sprightly rock steady beat featuring Bobby Ellis (trumpet), Roland Alphonso (saxophone) and Carlton Samuels’ (saxophone) harmonizing horns, Andy’s lyrics poignantly depict the challenges endured by Jamaica’s poor ("I can’t get no clothes to wear, can’t get no food to eat, I can’t get a job to get bread") while expressing a longing to return to Africa, a central theme within 1970s Rasta roots reggae.

The depth of Andy’s lyrics expanded the considerations of Jamaican songwriters and one of his primary influences was Bob Dylan. "When I heard Bob Dylan, it occurred to me for the first time that you don’t have to write songs about heart and soul," Andy told Billboard in 2018. "Bob Dylan’s music introduced me to the world of social commentary and that set me on my way as a writer."

Dawn Penn - "You Don’t Love Me" (1967)

Dawn Penn’s plaintive, almost trancelike vocals and the lilting rock steady arrangement by the Soul Vendors transformed Willie Cobbs’ early R&B hit "You Don’t Love Me," based on Bo Diddley’s 1955 gritty blues lament "She’s Fine, She’s Mine," into a Jamaican classic. The song’s shimmering guitar intro gives way to the forceful drum and bass with Mittoo’s keyboards providing an understated yet essential flourish.

In 1992 Jamaica’s Steely and Clevie remade the song, featuring Penn, for their album Steely and Clevie Play Studio One Vintage. The dynamic musician/production duo brought their mastery (and 1990s technological innovations) to several Studio One classics with the original singers. Heartbeat released "You Don’t Love Me" as a single and it reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Several artists have reworked Penn’s rendition or sampled the Soul Vendors’ arrangement including rapper Eve on a collaboration with Stephen and Damian Marley. Rihanna recruited Vybz Kartel for an interpretation included on her 2005 debut album Music of the Sun, while Beyoncé performed the song on her I Am world tour in 2014 and recorded it in 2019 for her Homecoming: The Live Album. In 2013, Los Angeles-based Latin soul group the Boogaloo Assassins brought a salsa flavor to Penn's tune, creating a sought-after DJ single.

The Heptones - "Equal Rights" (1968)

"Every man has an equal right to live and be free/no matter what color, class or race he may be," sings an impassioned Leroy Sibbles on "Equal Rights," the Heptones’ stirring plea for justice.

Harmony vocalist Earl Morgan formed the group with singer Barry Llewellyn in the early '60s and Sibbles joined them a few years later. The swinging bass line, played by Sibbles, anchors a stunning rock steady rhythm track awash in cascading horns, and blistering percussion patterns akin to the akete or buru drums heard at Rastafari Nyabinghi sessions.

Besides leading the Heptones’ numerous hit singles during their five-year stint at Studio One, Sibbles was a talent scout, backing vocalist, resident bassist and the primary arranger, alongside Jackie Mittoo. Sibbles’ progressive basslines are featured on numerous Studio One nuggets (many appearing on this list) and have been sampled or remade countless times over the decades on Jamaican and international hits.

In a December 2023 interview Sibbles echoed a complaint expressed by many who worked at Studio One: Dodd didn’t fairly compensate his artists and the (uncredited) musicians produced the songs while Dodd tended to business matters. "When we started out, we didn’t know about the business, and what happened, happened. But as you learn as you go along," he said. "I have registered what I could; I am living comfortably so I am grateful."

The Cables - "Baby Why" (1968)

Formed in 1962 by lead singer Keble Drummond and backing vocalists Vincent Stoddart and Elbert Stewart, the Cables — while not as well-known as the Wailers, the Maytals or the Heptones — recorded a few evergreen hits at Studio One, including the enchanting "Baby Why."

Keble’s aching vocals lead this breakup tale as he warns the woman who left that she’ll soon regret it. The simple story line is delivered via a gorgeous melody that’s further embellished by Vincent and Elbert’s superb harmonizing, repeatedly cooing to hypnotic effect "why, why oh, why?"

Coxsone is said to have kept the song for exclusive sound system play for several months; when he finally released it commercially, "Baby Why" stayed at No. 1 for four weeks.

"Baby Why" is notable for another reason: although the Maytals’ "Do The Reggay" marks the initial use of the word reggae in a song, "Baby Why" is among a handful of songs cited as the first recorded with a reggae rhythm (reggae basslines are fuller and reggae’s tempo is a bit slower than its rocksteady forerunner.) Other contenders for that historic designation include Lee "Scratch Perry’s "People Funny Boy," the Beltones’ "No More Heartache," and Larry Marshall and Alvin Leslie’s delightful "Nanny Goat."

Burning Spear - "Door Peeper" (1969)

Hailing from the parish of St. Ann, Jamaica, Burning Spear was referred to Studio One by another St. Ann native, Bob Marley. Spear’s first single for Studio One "Door Peeper" (also known as "Door Peep Shall Not Enter") recorded in 1969, sounded unlike any music released by Dodd and was critical in shaping the Rastafarian roots reggae movement of the next decade.

The song’s biblically laced lyrics caution informers who attempt to interfere with Rastafarians, considered societal outcasts at the time in Jamaica, while Spear’s intonation to "chant down Babylon" creates a haunting mystical effect, supported by Rupert Willington’s evocative, deep vocal pitch, a throbbing bass, mesmeric percussion and magnificent horn blasts.

As Spear told GRAMMY.com in September 2023, "When Mr. Dodd first heard 'Door Peep' he was astonished; for a man who’d been in the music business for so long, he never heard anything like that." Dodd’s openness to recording Rasta music, and allowing ganja smoking on the premises (but not in the studio) when his competitors didn’t put him in the forefront at the threshold of the roots reggae era.

"Door Peeper" was included on Burning Spear’s debut album, Studio One Presents Burning Spear, released in 1973 and remains a popular selection in the legendary artist’s live sets.

Joseph Hill - "Behold The Land" (1972)

In the October 1946 address Behold The Land by W. E. B. DuBois at the closing session of the Southern Youth Legislature in Columbia, South Carolina, the then 78-year-old celebrated author and activist urges Black youth to fight for racial equality and the civil rights denied them in Southern states. The late Joseph Hill’s 1972 song of the same name, possibly influenced by Dubois’ words, is a powerful reggae missive exploring the atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade from which descended the discriminations DuBois described.

Hill was just 23 when he wrote/recorded "Behold The Land," his debut single as a vocalist. Hill’s haunting timbre summons the harrowing experience with the wisdom and emotional rendering of an ancestor: "For we were brought here in captivity, bound in links and chains and we worked as slaves and they lashed us hard." Hill then gives praise and asks for repatriation to the African motherland, "let us behold the land where we belong."

The Soul Defenders — a self contained entity but also a Studio One house band with whom Hill made his initial recordings as a percussionist — provide a persistent, bass heavy rhythm that suitably frames Hill’s lyrical gravitas, as do the melancholy hi-pitched harmonies.

In 1976 Hill formed the reggae trio Culture and the next year they catapulted to international fame with their apocalyptic single "Two Sevens Clash," which prompted Dodd to finally release "Behold The Land." Culture would re-record "Behold The Land" over the years including for their 1978 album Africa Stand Alone and the song received a digital remastering in 2001.

Sugar Minott - "Oh Mr. DC" (1978)

In the mid-1970s singer Lincoln "Sugar" Minott began writing lyrics to classic 1960s Studio One riddims, an approach that launched his hitmaking solo career and further popularized the practice of riddim recycling — which is still a standard approach in dancehall production. Sugar, formerly with the vocal trio The African Brothers, penned one of his earliest solo hits "Oh, Mr. DC" to the lively beat of the Tennors’ 1967 single "Pressure and Slide" (itself a riddim originally heard, at a faster pace, underpinning Prince Buster’s 1966 "Shaking Up Orange St.")

"Oh, Mr. DC" is an authentic tale of a ganja dealer returning from the country with his bag of collie (marijuana); the DC (district constable/policeman) says he’s going to arrest him and threatens to shoot if he attempts to run away. Sugar explains to the officer that selling herb is how he supports his family: "The children crying for hunger/ I man a suffer, so you’ve got to see/it’s just collie that feed me." To underscore his urgent plea, Sugar wails in an unforgettable melody, "Oh, oh DC, don’t take my collie."

The irresistibly bubbling bassline of the riddim nearly obscures the song’s poignant depiction of Jamaica’s harsh economic realities and the potential risk of imprisonment, or worse, that the island’s ganja sellers faced at the time. Sugar’s revival of a Studio One riddim and reutilization of 10 Studio One riddims for each track of his 1977 album Live Loving brought renewed interest to the treasures that could be extracted from Mr. Dodd’s vaults.

Special thanks to Coxsone Dodd’s niece Maxine Stowe, former A&R at Sony/Columbia and Island Records, who started her career at Coxsone’s Music City, Brooklyn.

How 'The Harder They Come' Brought Reggae To The World: A Song By Song Soundtrack Breakdown

Photo: William Richards, courtesy of VP Records

feature

Morgan Heritage’s 'Don’t Haffi Dread' At 25: How Rasta Sibling Group Created A Roots Rock Anthem & Brought Spirituality To The World

In their first interview since the passing of Peetah Morgan, siblings Una, Gramps and Mojo of GRAMMY-winning reggae band Morgan Heritage reflect on the 25th anniversary of their breakthrough roots reggae album.

In the late '90s, a time when synthesized dancehall riddims dominated Jamaica’s airwaves, Rastafarian sibling band Morgan Heritage remained steadfast in their dedication to roots reggae. Their passion would resonate internationally via 1999's Don’t Haffi Dread, an album that brought renewed vitality and youthful enthusiasm to roots reggae.

Released via New York label VP Records on March 23, 1999, Don’t Haffi Dread was a personal and professional advancement for Morgan Heritage, earning the band widespread accolades and a designation as reggae’s future. Filled with rebel statements, spiritually empowering sentiments and R&B-infused lover’s rock, Don’t Haffi Dread is perhaps remembered most for its title track. The song's catchy and somewhat contentious lyric, "yuh don’t haffi dread to be rasta," asserted that listeners don't have to wear dreadlocks to embrace Rastafari’s teachings.

Decades later, the song remains one of the most popular in the group’s expansive catalog. "That was the first time a Rastafarian said something like that on record," the group’s lead singer Peetah Morgan told me at the time of Don’t Haffi Dread’s release, in an interview for Air Jamaica’s SkyWritings Magazine. "It caused a lot of controversy and got us a lot of attention, even in places we had never performed."

Although it was the band’s fourth album, Don’t Haffi Dread was the first time they recorded playing their instruments live in the studio. This was a remarkable achievement, Peetah explained, "because it was done at a time when we were told live recording would never come back to Jamaica."

Peetah’s vocal dynamism led the band’s many heartfelt appeals for unity as persuasively as his paeans to Jah can stir the souls of the most hardened non-believers. He died at age 50 on Feb. 25.

"The journey has been a blessing. May God continue to keep our brother Peetah," says keyboardist and vocalist Una Morgan. "Our dad used to compare us to a body with two hands, two feet and Peetah was our head; to be celebrating this album in Peetah’s honor is the greatest feeling ever."

In their first interview since Peetah's passing, members of Morgan Heritage reflected on the 25th anniversary of their breakthrough album. "Recording Don’t Haffi Dread…we honed our craft and became a force to be looked at; now we are called icons, legends," Una continues.

Don’t Haffi Dread established Morgan Heritage as one reggae’s most popular acts and one the very few self-contained bands to emerge from Jamaica in the 1990s. "Everything opened up for Morgan Heritage with the release of Don’t Haffi Dread," comments Cristy Barber, former Head of A&R, VP Records. "They were featured on a segment on 'CBS Sunday Morning' with their father; they played a private party for Johnny Cash, performed before an audience of millions on the televised Special Olympics and became the first reggae band on the Vans Warped Tour."

Morgan Heritage are five of the 30 children of the late Jamaican singer Denroy Morgan, whose 1981 hit "I’ll Do Anything For You" reached the Top 10 on Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart. Siblings Memmalatel "Mr. Mojo" (percussion, vocals), Nakhamyah "Lukes" (guitar), Roy "Gramps," (vocals, keyboards), and the band’s sole female member Una, and Peetah were raised in Rastafarian households. They lived in Springfield, Massachusetts, where they attended school, and spent weekends in Brooklyn, immersed in music studies.

In 1992, Morgan Heritage was an eight member aggregation that included older siblings David, Denroy Jr. and Jeffrey. Immediately following their debut performance at Jamaica’s now defunct Reggae Sunsplash festival, they were signed to MCA Records and released one album, 1994's pop-reggae leaning Miracle. Displeased with the label’s lack of support, the Morgans chose not to record a second album for the company. With their increasing personal responsibilities, including caring for their young children, David, Denroy Jr., and Jeffreyleft the group.

However, it was papa Denroy’s decision to return to his Jamaica birthplace in 1995 that put Morgan Heritage on their path to success. Morgan Heritage’s remaining five members, now in their early to mid 20s, followed their dad to Jamaica. The band spent over a year alternating between morning recording sessions with producer Lloyd "King Jammy" James and afternoons with producer Robert "Bobby Digital" Dixon. The band wrote songs and recorded their vocals over pre-made riddims (rhythm tracks), a standard practice in Jamaican music making. Their diligence yielded two albums: the Digital-produced Protect Us Jah and One Calling, produced by Jammy.

The band returned to Bobby Digital (whose extensive production resume includes landmark albums by Sizzla, the late Garnet Silk and multiple hit singles by Shabba Ranks) to produce Don’t Haffi Dread. This time, they played their own instruments alongside other musicians live on the album’s recording sessions.

"The riddim thing is part of Jamaican culture but with Don’t Haffi Dread, our father pulled the reins and said, that’s not how the greats do it," Gramps explains, adding, with a Jamaican inflection, "yuh don’t hear Michael Jackson say to Quincy Jones, 'Let mi vibe something on di riddim!'

"Our father always said, you have to do this at the highest level because you have great potential," Gramps continues. "Bobby trusted the process and gave us artistic freedom so Don’t Haffi Dread was a turning point: We got out our guitars, wrote songs, brought them to the studio and played/recorded them live."

Written by Gramps and Peetah, "Don’t Haffi Dread" utilizes shimmering guitar riffs that underscore the melodic sing-along chorus delivered by Peetah with innate emotional conviction and precocious wisdom that made it a 21st century reggae anthem. There are two versions of "Don’t Haffi Dread" on the album, including an exquisite acoustic guitar rendition that closes the set.

"We wrote that song in Brooklyn, it was our truth growing up in the Twelve Tribes of Israel branch of Rastafari (Bob Marley was a member), which was about bringing together Jah’s children from afar," explains Gramps. "We saw white Rastas, Asian Rastas, Rastas in New Zealand, Australia and Mexico. We knew it wasn’t about growing dreadlocks, wearing an Emperor Halie Selassie I button or even dietary laws. It was about how we lived, the love in our hearts. By sharing our truth, many people realized they didn’t have to wear dreadlocks to identify with the messages of Rastafari."

The Rastafari way of life originated in Jamaica in the 1930s, following the crowning of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I, whom Rastas recognize as the Messiah. Many early Rasta adherents wearing dreadlocks faced continuous persecution, their locks forcibly shorn, their housing settlements demolished while others were killed by authorities just for their way of life. Some listeners perceived "Don’t Haffi Dread" as insensitive to that suffering.

"The division, the uproar that took place…provided clarity like nothing else in our life," shares Mojo. "Seeing the impact of our music on a global scale, the effect it had on human lives was an epiphany; we realized that we’re here for more than just a good time and that gave us a sense of purpose. We started to understand the assignment before that term came about. The conviction and messages heard throughout our music is because of our experiences with Don’t Haffi Dread."

Rasta anthems and socially conscious statements abound on Don’t Haffi Dread. The rousing "Earthquake," is a "chant down Babylon" style tribute to Rasta elders; "Ready to Work" offers a clarion call to rise up, unify and change the world. The acoustic guitar-driven plea on "Freedom," a powerful missive that parallels the most effective songs that soundtracked the civil rights movement, features Gramps’ robust baritone, Mojo’s rapped rhymes and Una’s graceful harmonies, each complementing Peetah’s stunning vibrato rendering.

Bobby Digital’s burnished production utilizes a few premade riddims. A bubbling interpolation of the musical backing to Bob Marley’s "Bend Down Low" undergirds "Reggae Bring Back Love," an engaging celebration of the genre's positive vibrations, highlighted by Peetah’s exuberant vocals. While not originally intended for Don’t Haffi Dread, "Reggae Bring Back Love" became one of its biggest hits, as Gramps recollects.

"Bobby gave us a cassette of the riddim as we were leaving the studio. We got in the car, pushed in the cassette and just before we pulled off, Peetah started singing ‘reggae bring back love’ over the riddim. We went back inside and recorded the song in less than 10 minutes," he recalls. "Bobby was so excited," adds Una, "he said, ‘dis is why mi love dat group yah.’"

With the release of Don’t Haffi Dread, Morgan Heritage became — and has remained — one of reggae’s busiest touring outfits, taking their impassioned, spell-binding performances around the world, fronted by Peetah Morgan’s charismatic voice. Peetah’s passing is the profound loss of a gifted, generation-defining singer and a beloved brother whose spirit will inform his siblings’ future plans.

"When Lukes and Una came off the road (in 2015 and 2017, respectively) Peetah, Mojo and I carried it," Gramps muses. "Now Peetah is gone. We’re still grieving but we know Peetah would have kicked us in our butts and said, ‘gwaan and do Jah work,’ so, the legacy must continue."

Living Legends: Stephen Marley On Old Soul, Being A Role Model & The Bob Marley Biopic

Photo: Gregg DeGuire/WireImage/Getty Images

news

7 Things We Learned Watching 'Bob Marley: One Love'

Starring Kingsley Ben-Adir, 'Bob Marley: One Love' takes viewers inside the tumultuous world of late '70s Jamaica as Marley prepares to release 'Exodus.'

For so many modern music fans, Bob Marley is more of an image than an actual person.

The late reggae superstar died in 1981 — struck down by cancer when he was just 36 years old — and while his popularity has only grown in the 40-odd years since, audiences now might be more familiar with music’s vibes and Marley's image than they are with the man in totality.

A new movie starring Kingsley Ben-Adir seeks to rectify that. Produced by Ziggy, Rita and Cedella Marley, among others, Bob Marley: One Love highlights Marley’s music, family, and deep passion for Rastafarianism. The biopic also takes viewers inside the tumultuous world of late ‘70s Jamaica, when crime bosses battled colonizers and Marley prepared to release his 1977 album Exodus — the record Time Magazine would come to call "the best album of the 20th century."

Bob Marley: One Love is only in theaters. For those who can't make it out to the silver screen, read on for seven insights into Bob Marley’s life gleaned from the movie.

Bob Marley Had A Complicated Upbringing

In the movie, we learn that Bob Marley never really knew his dad. Marley's father is never shown in full, but depicted as this sort of faceless white colonist with nothing but contempt for his young son.

Bob’s mom moved to Delaware when the singer was quite young, following her marriage to an American civil servant, and a teenaged Bob was sort of left to fend for himself in Jamaica. It was then he met and fell in love with Rita Anderson, who introduced him to Rastafarianism.

Bob Believed His Music Could Bring People Peace

When the movie opens, we’re thrust into 1976, during which Jamaica was undergoing major political and economic turmoil. Crime bosses were warring, political rivals were clashing, and there was a lot of unrest in the street. While Bob took pains to not take sides at the time, he felt like he could help heal the country through music, planning the Smile Jamaica concert to bring people together.

Unfortunately, as we see in the movie, Bob’s homebase is invaded just before the tour, with Bob, Rita, and their manager suffering gunshot wounds. (According to the movie, the thickness of Rita’s dreads kept a bullet from hitting her brain.)

Read more: Living Legends: Stephen Marley On 'Old Soul,' Being A Role Model & The Bob Marley Biopic

Though people encourage him to flee the country after the shooting, Bob is committed to the show. He performs, though he appears rattled in the movie, ultimately sending his family off to Delaware and heading to London to get away from an increasingly untenable situation in his home country.

Rastafarianism Influenced Bob's Language & Songwriting

If you’ve always hummed along to cuts like "Redemption Song" but didn’t quite understand the meaning of lines like "Old pirates, yes they rob I," One Love is here to answer. Per the film, Rastafarians believe that "words separate people," meaning that there should be no "you" or "me," but rather just "I and I."

Bob’s love for Rasta life features prominently in the film, and there are revelations about how he thought that his music and the Rasta message were essentially the same thing. "Reggae," the film says, "is the vehicle" to spread the gospel of Haile Selassie and the idea of a Black God. Songs like "Natural Mystic" were, in Bob’s eyes, just classic Rasta messages set to catchy music.

That’s also partially where the idea for Exodus comes from, which we see the recording of in the film. One of Bob Marley's most important records, Exodus was inspired not only by the cinematic saga of the same name, but of the singer’s religious politics. While tracks like "Turn Your Lights Down Low" are pretty much torch songs, others, like "Exodus" are about the Rastafarians’ quest for a spiritual homeland, or, as the song puts it, the ongoing "movement of Jah people."

Bob Marley May Was A Visionary, But He Was No Saint

While we don’t get a real clear picture of what was going on with Bob and Rita’s marriage in One Love, we do catch some glimpses at random women giving Bob the eye, as well as a blowout fight between the two in which they both rail against the other’s infidelities.

While it’s well known that Bob fathered at least six children out of wedlock, two of his 11 or so claimed descendents are solely Rita’s kids, including one daughter she had before they were married and another conceived during an affair with a former Jamaican soccer player.

While Rita’s involvement in the movie would suggest that she doesn’t necessarily harbor any intractable feelings about what was going on outside their marital bed, the inclusion of some of the less savory parts of Bob’s personality serve to make him seem like a more complete human on-screen.

Bob Wasn't Concerned About The Almighty Dollar

Though Bob Marley’s estate is worth an estimated $500 million today, the movie makes it clear that the singer didn’t care all that much for money.

There’s archival interview footage of him during the credits pooh-pooing the notion that he was "rich," with him saying, "my richness is life." He’s also seen during the movie doling out money to needy Jamaicans, as well as to his band. At one point, Marley tells his manager that he doesn’t really care how much they make on a potential African tour, as long as they "have enough to pay the band."

Bob Died Of An Extremely Rare Cancer

Though it’s generally well-known that the late reggae icon died much too young, the circumstances of his death are discussed less often. As we see in One Love, Bob found out on July 7, 1977 — an auspicious day according to Marcus Garvey — that he had acral lentiginous melanoma, an extremely rare form of skin cancer that appears in generally ignored parts of the body, like on the soles of the feet or. In Bob’s case, the cancer appeared under a toenail.

Though his doctor recommended that Bob have his toe amputated to stem the spread of the disease, the singer rejected the notion, citing his religious beliefs as well as his performing career. The cancer would spread to Marley’s brain, lungs, and liver before he died a little shy of four years later.

The Marley Family Is Heavily Invested In Keeping Their Legacy Alive

One Love opens with an introduction from Ziggy Marley, who says that he was on set nearly every day the movie was in production. He added that he wanted to make sure the film captured his dad’s true essence, and it’s clear both from his speech and the work that he’s done since that he really does mean it.

The Marley family has always stayed close, recording and performing together quite a lot (Bob’s sons Damian and Stephen are touring this summer, for instance). Bob Marley: One Love seems to be just another extension of the love they have for their dad and for their whole family, as well as for the rich legacy their parents created together.

list

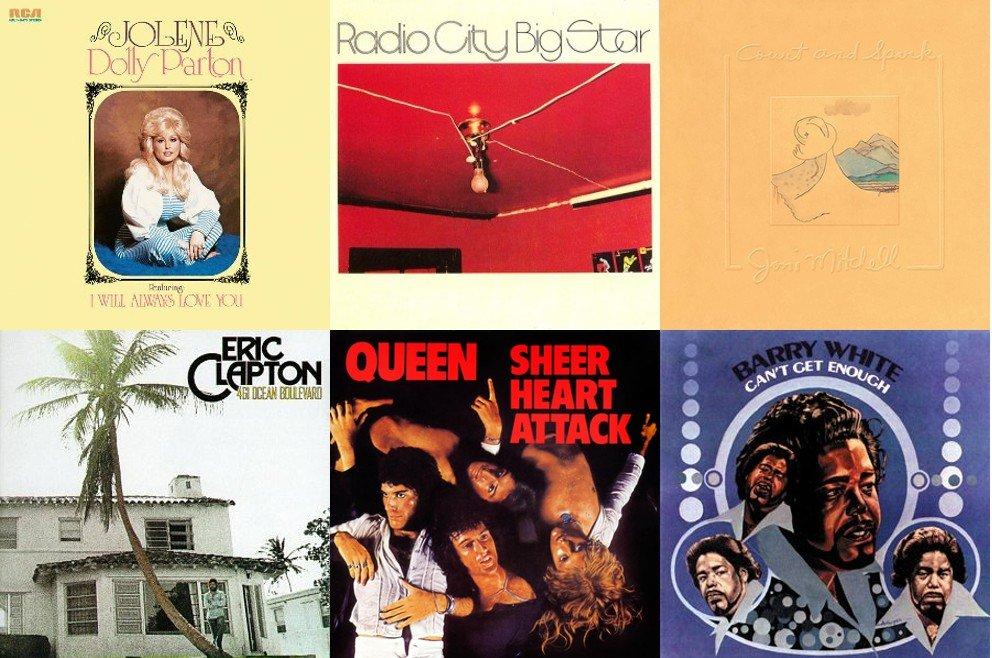

21 Albums Turning 50 In 2024: 'Diamond Dogs,' 'Jolene,' 'Natty Dread' & More

Dozens of albums were released in 1974 and, 50 years later, continue to stand the test of time. GRAMMY.com reflects on 21 records that demand another look and are guaranteed to hook first-time listeners.

Despite claims by surveyed CNN readers, 1974 was not a year marked by bad music. The Ramones played their first gig. ABBA won Eurovision with the earworm "Waterloo," which became an international hit and launched the Swedes to stardom. Those 365 days were marked by chart-topping debuts, British bangers and prog-rock dystopian masterpieces. Disenchantment, southern pride, pencil thin mustaches and tongue-in-cheek warnings to "not eat yellow snow" filled the soundwaves.

1974 was defined by uncertainty and chaos following a prolonged period of crisis. The ongoing OPEC oil embargo and the resulting energy shortage caused skyrocketing inflation, exacerbating the national turmoil that preceded President Nixon’s resignation following the Watergate scandal. Other major events also shaped the zeitgeist: Stephen King published his first novel, Carrie, Muhammad Ali and George Foreman slugged it out for the heavyweight title at "The Rumble in the Jungle," and People Magazine published its first issue.

Musicians reflected a general malaise. Themes of imprisonment, disillusionment and depression — delivered with sardonic wit and sarcasm — found their way on many of the records released that year. The mood reflects a few of the many reasons these artistic works still resonate.

From reggae to rock, cosmic country to folk fused with jazz, to the introduction of a new Afro-Trinidadian music style, take a trip back 18,262 days to recall 20 albums celebrating their 50th anniversaries in 2024.

Joni Mitchell - Court & Spark

Joni Mitchell’s Court & Spark is often hailed as the pinnacle of her artistic career and highlights the singer/songwriter’s growing interest in jazz, backed by a who’s who of West Coast session musicians including members of the Crusaders and L.A. Express.

As her most commercially successful record, the nine-time GRAMMY winner presents a mix of playful and somber songs. In an introspective tone, Mitchell searches for freedom from the shackles of big-city life and grapples with the complexities of love lost and found. The record went platinum — it hit No.1 on the Billboard charts in her native Canada and No. 2 in the U.S., received three GRAMMY nominations and featured a pair of hits: "Help Me" (her only career Top 10) and "Free Man in Paris," an autobiographical song about music mogul David Geffen.

Gordon Lightfoot - Sundown

In 2023 we lost legendary songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. He left behind a treasure trove of country-folk classics, several featured on his album Sundown. These songs resonated deeply with teenagers who came of age in the early to mid-1970s — many sang along in their bedrooms and learned to strum these storied songs on acoustic guitars.

Recorded in Toronto, at Eastern Sound Studios, the album includes the only No.1 Billboard topper of the singer/songwriter’s career. The title cut, "Sundown," speaks of "a hard-loving woman, got me feeling mean" and hit No. 1 on both the pop and the adult contemporary charts.

In Canada, the album hit No.1 on the RPM Top 100 in and stayed there for five consecutive weeks. A second single, "Carefree Highway," peaked at the tenth spot on the Billboard Hot 100, but hit No.1 on the Easy Listening charts.

Eric Clapton - 461 Ocean Boulevard

Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard sold more than two million copies worldwide. His second solo studio record followed a three-year absence while Clapton battled heroin addiction. The record’s title is the address where "Slowhand" stayed in the Sunshine State while recording this record at Miami’s Criteria Studios.

A mix of blues, funk and soulful rock, only two of the 10 songs were penned by the Englishman. Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s "I Shot the Sheriff," was a massive hit for the 17-time GRAMMY winner and the only No.1 of his career, eclipsing the Top 10 in nine countries. In 2003, the guitar virtuoso’s version of the reggae song was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

Lynyrd Skynyrd - Second Helping

No sophomore slump here. This "second helping" from these good ole boys is a serious serving of classic southern rock ‘n’ roll with cupfuls of soul. Following the commercial success of their debut the previous year, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s second studio album featured the band’s biggest hit: "Sweet Home Alabama."

The anthem is a celebration of Southern pride; it was written in response to two Neil Young songs ("Alabama" and "Southern Man") that critiqued the land below the Mason-Dixon line. The song was the band’s only Top 10, peaking at No. 8 on the Billboard Top 100. Recorded primarily at the Record Plant in Los Angeles, other songs worth a second listen here include: the swampy cover of J.J. Cale's "Call Me The Breeze," the boogie-woogie foot-stomper "Don’t Ask Me No Questions" and the country-rocker "The Ballad of Curtis Loew."

Bad Company - Bad Company

A little bit of blues, a token ballad, and plenty of hard-edged rock, Bad Company released a dazzling self-titled debut album. The English band formed from the crumbs left behind by a few other British groups: ex-Free band members including singer Paul Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke, former King Crimson member bassist Boz Burrel, and guitarist Mick Ralphs from Mott the Hoople.

Certified five-times platinum, Bad Company hit No.1 on the Billboard 200 and No. 3 in the UK, where it spent 25 weeks. Recorded at Ronnie Lane’s Mobile Studio, the album was the first record released on Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label. Five of the eight tracks were in regular FM rotation throughout 1974; "Bad Company," "Can’t Get Enough" and "Ready for Love" remain staples of classic rock radio a half century later.

Supertramp - Crime of the Century

"Dreamer, you know you are a dreamer …" sings Supertramp’s lead singer Roger Hodgson on the first single from their third studio album. The infectious B-side track "Bloody Well Right," became even more popular than fan favorite, "Dreamer."

The British rockers' dreams of stardom beyond England materialized with Crime of the Century. The album fused prog-rock with pop and hit all the right notes leading to the band’s breakthrough in several countries — a Top 5 spot in the U.S. and a No.1 spot in Canada where it stayed for more than two years and sold more than two million copies. A live version of "Dreamer," released six years later, was a Top 20 hit in the U.S.

Big Star - Radio City

As one of the year’s first releases, the reception for this sophomore effort from American band Big Star was praised by critics despite initial lukewarm sales (which were due largely to distribution problems). Today, the riveting record by these Memphis musicians is considered a touchstone of power pop; its melodic stylings influenced many indie rock bands in the 1980s and 1990s, including R.E.M. and the Replacements. One of Big Star’s biggest songs, "September Gurls," appears here and was later covered by The Bangles.

In a review, American rock critic Robert Christgau, called the record "brilliant and addictive." He wrote: "The harmonies sound like the lead sheets are upside down and backwards, the guitar solos sound like screwball readymade pastiches, and the lyrics sound like love is strange, though maybe that's just the context."

The Eagles - On the Border

The third studio record from California harmonizers, the Eagles, shows the band at a crossroads — evolving ever so slightly from acoustically-inclined country-folk to a more distinct rock ‘n’ roll sound. On the Border marks the studio debut for band member Don Felder. His contributions and influence are seen through his blistering guitar solos, especially in the chart-toppers "Already Gone" and "James Dean."

On the Border sold two million copies, driven by the chart topping ballad "Best of My Love" — the Eagles first No.1 hit song. The irony: the song was one of only two singles Glyn Johns produced at Olympic Studios in London. Searching for that harder-edged sound, the band hired Bill Szymczyk to produce the rest of the record at the Record Plant in L.A.

Jimmy Buffett - Livin’ and Dyin in ¾ Time & A1A

Back in 1974, 28-year-old Jimmy Buffett was just hitting his stride. Embracing the good life, Buffett released not just one, but two records that year. Don Grant produced both albums that were the final pair in what is dubbed Buffett’s "Key West phase" for the Florida island city where the artist hung his hat during these years.

The first album, Livin’ and Dyin’ in ¾ Time, was released in February and recorded at Woodland Sound Studio in Nashville, Tennessee. It featured the ballad "Come Monday," which hit No. 30 on the Hot 100 and "Pencil Thin Mustache," a concert staple and Parrothead favorite. A1A arrived in December and hit No. 25 on the Billboard 200 charts. The most beloved songs here are "A Pirate Looks at Forty" and "Trying to Reason with Hurricane Season."

Buffett embarked on a tour and landed some plume gigs, including opening slots for two other artists on this list: Frank Zappa and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Genesis - The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

Following a successful tour of Europe and North America for their 1973 album, Selling England by the Pound, Genesis booked a three-month stay at the historic Headley Grange in Hampshire, a former workhouse. In this bucolic setting, the band led by frontman Peter Gabriel, embarked on a spiritual journey of self discovery that evolved organically through improvisational jams and lyric-writing sessions.

This period culminated in a rock opera and English prog-rockers’s magnum opus, a double concept album that follows the surreal story of a Puerto Rican con man named Rael. Songs are rich with American imagery, purposely placed to appeal to this growing and influential fan base across the pond.

This album marked the final Genesis record with Gabriel at the helm. The divisiveness between the lyricist, Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks came to a head during tense recording sessions and led to Gabriel’s departure from the band to pursue a solo career, following a 102-date tour to promote the record. The album reached tenth spot on the UK album charts and hit 41 in the U.S.

David Bowie - Diamond Dogs

Is Ziggy Stardust truly gone? With David Bowie, the direction of his creative muse was always a mystery, as illustrated by his diverse musical legacy. What is clear is that Bowie’s biographers agree that this self-produced album is one of his finest works.

At the point of producing Diamond Dogs, the musical chameleon and art-rock outsider had disbanded the band Spiders from Mars and was at a crossroads. His plans for a musical based on the Ziggy character and TV adaptation of George Orwell’s "1984" both fell through. In a place of uncertainty and disenchantment, Bowie creates a new persona: Halloween Jack. The record is lyrically bleak and evokes hopelessness. It marks the final chapter in his glam-rock period — "Rebel Rebel" is the swaggering single that hints at the coming punk-rock movement.

Bob Marley - Natty Dread

Bob Marley’s album "Natty Dread," released first in Jamaica in October 1974 later globally in 1975, marked his first record without his Rastafari brethren in song Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer. It also introduced the back-up vocal stylings of the I Threes (Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths.)

The poet and the prophet Marley waxes on spiritual themes with songs like "So Jah Seh/Natty Dread'' and political commentary with tracks,"Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)" and "Rebel Music (3 O’clock Road Block)." The album also Includes one of the reggae legend’s best-loved songs, the ballad "No Woman No Cry," which paints a picture of "government yards in Trenchtown" where Marley’s feet are his "only carriage."

Queen - Sheer Heart Attack

The third studio album released by the British rockers, Queen, is a killer. The first single, "Killer Queen," reached No. 2 on the British charts — and was the band’s first U.S. charting single. The record also peaked at No.12 in the U.S. Billboard albums charts.

This record shows the four-time GRAMMY nominees evolving and shifting from progressive to glam rock. The album features one of the most legendary guitar solos and riffs in modern rock by Brian May on "Brighton Rock." Clocking in at three minutes, the noodling showcases the musician’s talent via his use of multi-tracking and delays to great effect.

Randy Newman - Good Old Boys

Most recognize seven-time GRAMMY winner Randy Newman for his work on Hollywood blockbuster scores. But, in the decade before composing and scoring movie soundtracks, the songwriter wrote and recorded several albums. Good Old Boys was Newman’s fourth studio effort and his first commercial breakthrough, peaking at No. 36 on the Billboard charts.

The concept record, rich in sarcasm and wit, requires a focused listen to grasp the nuances of Newman’s savvy political and social commentary. The album relies on a fictitious narrator, Johnny Cutler, to aid the songwriter in exploring themes like "Rednecks" and ingrained generational racism in the South. "Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man)" is as relevant today as when Newman penned it as a direct letter to Richard Nixon. Malcolm Gladwell described this record as "unsettling" and a "perplexing work of music."

Frank Zappa - Apostrophe

Rolling Stone once hailed Frank Zappa’s Apostrophe as "truly a mother of an album." The album cover itself, featuring Zappa’s portrait, seems to challenge listeners to delve into his eccentric musical universe. Apostrophe was the sixth solo album and the 19th record of the musician’s prolific career. The album showcases Zappa’s tight and talented band, his trademark absurdist humor and what Hunter S. Thompson described as "bad craziness."

Apostrophe was the biggest commercial success of Zappa’s career. The record peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard Top 200. The A-side leads off with a four-part suite of songs that begins with "Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow" and ends with "Father Oblivion," a tale of an Eskimo named Nanook. The track "Uncle Remus," tackles systemic racism in the U.S. with dripping irony. In less than three minutes, Zappa captures what many politicians can’t even begin to explain. Musically, Apostrophe is rich in riffs from the two-time GRAMMY winner that showcases his exceptional guitar skills in the title track that features nearly six minutes of noodling.

Gram Parsons - Grievous Angel

Grievous Angel can be summed up in one word: haunting. Recorded in 1973 during substance-fueled summer sessions in Hollywood, the album was released posthumously after Gram Parsons died of a drug overdose at 26. Grievous Angel featured only two new songs that Parsons’ penned hastily in the studio "In My Hour of Darkness" and "Return of the Grievous Angel."

This final work by the cosmic cowboy comprises nine songs that have since come to define Parson’s short-lived legacy to the Americana canon. The angelic voice of Emmylou Harris looms large — the 13-time GRAMMY winner sings harmony and backup vocals throughout. Other guests include: guitarists James Burton and Bernie Leadon, along with Linda Ronstadt’s vocals on "In My Hour of Darkness."

Neil Young - On The Beach

On the Beach, along with Tonight’s the Night (recorded in 1973, but not released until 1975) rank as Neil Young’s darkest records. Gone are the sunny sounds of Harvest, replaced with the singer/songwriter’s bleak and mellow meditations on being alone and alienated.

"Ambulance Blues" is the centerpiece. The nine-minute track takes listeners on a journey back to Young’s "old folkie days" when the "Riverboat was rockin’ in the rain '' referencing lament and pining for time and things lost. The heaviness and gloom are palpable throughout the album, with the beach serving as an extended metaphor for Young’s malaise.

Dolly Parton - Jolene

Imagine writing not just one, but two iconic classics in the same day. That’s exactly what Dolly Parton did with two tracks featured on this album. The first is the titular song, "Jolene," recorded at RCA Studio B in Nashville. The song has been covered by more than a dozen artists.

Released as the first single the previous fall, "Jolene," rocketed to No.1 on the U.S. country charts and garnered the 10-time GRAMMY winner her first Top 10 in the U.K. The song was nominated for a GRAMMY in 1975 and again in 1976 for Best Country Vocal Performance. However, it didn’t take home the golden gramophone until 2017, when a cover by the Pentatonix featuring Parton won a GRAMMY for Best Country Duo/Group Performance.

Also included on this album is "I Will Always Love You," a song that Whitney Houston famously covered in 1992 for the soundtrack of the romantic thriller, The Bodyguard, earning Parton significant royalties.

Barry White - Can’t Get Enough

The distinctive bass-baritone of two-time GRAMMY winner Barry White, is unmistakable. The singer/songwriter's sensual, deep vocal delivery is as loved today as it was then. On this record, White is backed by the 40-member strong Love Unlimited Orchestra, one of the best-selling artists of all-time.

White wrote "Can’t Get Enough of Your Love, Babe," about his wife during a sleepless night. This song is still played everywhere — from bedrooms to bar rooms, even 50 years on. In the U.S., the record hit the top of the R&B pop charts and No.1 on the Billboard 200. Although the album features only seven songs, two of them, including "You’re the First, the Last, My Everything" reached the top spot on the R&B charts.

Lord Shorty - Endless Vibrations

Lord Shorty, born Garfield Blackman, is considered the godfather and inventor of soca music. This Trindadian musician revolutionized his nation’s Calypso rhythms, creating a vibrant up-tempo style that became synonymous with their world-renowned Carnival.

Fusing Indian percussion instrumentation with well-established African calypso rhythms, Lord Shorty created what he originally dubbed "sokah," meaning, "calypso soul." The term soca, as it’s known today, emerged because of a journalist’s altered writing of the word, which stuck. The success of this crossover hit made waves across North America and made the island vibrations more accessible outside the island nation.

Artists Who Are Going On Tour In 2024: The Rolling Stones, Drake, Olivia Rodrigo & More