Photo: John Rogers

list

10 Albums That Showcase The Deep Connection Between Jazz And Electronic Music: Herbie Hancock, Flying Lotus, Caroline Davis & More

Jazz has long stretched the parameters of harmony, melody and rhythm — and when electronic music flows into it, the possibilities are even more limitless.

A year and change before his 2022 death, the eminent saxophonist Pharoah Sanders released one final dispatch. That album was Promises, a meditative, collaborative album with British electronic musician Floating Points and the London Symphony Orchestra.

Promises swung open the gates for jazz and electronic music's convergence.. Not only was it an out-of-nowhere critical smash, earning "universal acclaim" as per Metacritic; it acted as an accessible entrypoint for the hipster set and beyond.

As Pitchfork put it, "One of the year's most memorable melodies consists of a seven-note refrain repeated, with slight variation, for more than three quarters of an hour." (They declared Promises the fourth best album of the year; its neighbors included Turnstile; Tyler, the Creator; and Jazmine Sullivan.)

Since then, jazz and electronic music have continued their developments, with or without each other. But Promises struck a resonant chord, especially during the pandemic years; and when Sanders left us at 81, the music felt like his essence lingering in our midst.

Whether you're aware of that crossover favorite or simply curious about this realm, know that the rapprochement between jazz and electronic idioms goes back decades and decades.

Read on for 10 albums that exemplify this genre blend — including two released this very year.

Miles Davis - Live-Evil (1971)

As the 1960s gave away to the '70s, Miles Davis stood at his most extreme pivot point — between post-bop and modal classics and undulating, electric exploits. Straddling the studio and the stage, Live-Evil is a monument to this period of thunderous transformation.

At 100 minutes, the album's a heaving, heady listen — its dense electronic textures courtesy of revered keyboardists Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and Joe Zawinul, as well as the combustible electric guitarist John McLaughlin. The swirling, beatless "Nem Un Talvez" is arguably Live-Evil's most demonstrative example of jazz meets electronic.

For the uninitiated as per Davis' heavier, headier work, Live-Evil is something of a Rosetta stone. From here, head backward in the eight-time GRAMMY winner and 32-time nominee's catalog — to In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew or Jack Johnson.

Or, move forward to On the Corner, Get Up With It or Aura. Wherever you move in his later discography, plenty of jazz fans wish they could hear this game-changing music for the first time.

Herbie Hancock - Future Shock (1983)

In the early 1970s, Herbie Hancock delivered a one-two punch of fusion classics — 1973's Head Hunters and 1974's Thrust — to much applause. The ensuing years told a different story.

While the 14-time GRAMMY winner and 34-time nominee's ensuing live albums tended to be well-regarded, his studio work only fitfully caught a break from the critics.

However, in 1983, Hancock struck gold in that regard: the inspired Future Shock wittily and inventively drew from electro-funk and instrumental hip-hop. Especially its single, "Rockit" — shot through with a melodic earworm, imbued with infectious DJ scratches.

Sure, it's of its time — very conspicuously so. But with hip-hop's 50th anniversary right in our rearview, "Rockit" sounds right on time.

Tim Hagans - Animation • Imagination (1999)

If electric Miles is your Miles, spring for trumpeter Tim Hagans' Animation • Imagination for an outside spin on that aesthetic.

The late, great saxophonist Bob Belden plays co-pilot here; he wrote four of its nine originals and produced the album. Guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel, synthesist Scott Kinsen, bassist David Dyson, and drummer Billy Kilson also underpin these kinetic, exploratory tunes.

The engine of Animation • Imagination is its supple and infectious sense of groove, whether in breakbeat ("Animation/Imagination"), boom bap ("Slo Mo") or any other form.

This makes the drumless moments, like "Love's Lullaby," have an indelible impact; when the drums drop out, inertia propels you forward. And on the electronics-swaddled "Snakes Kin," the delayed-out percussion less drives the music than rattles it like an angry hive.

Kurt Rosenwinkel - Heartcore (2003)

From his language to his phrasing to his liquid sound, Rosenwinkel's impact on the contemporary jazz guitar scene cannot be overstated: on any given evening in the West Village, you can probably find a New Schooler laboriously attempting to channel him.

Rosenwinkel's appeared on more than 150 albums, so where to begin with such a prodigious artist? One gateway is Heartcore, his first immersion into electronic soundscapes as a bandleader.

Throughout, the laser-focused tenor saxophonist Mark Turner is like another half of his sound. On "Our Secret World," his earthiness counter-weighs Rosenwinkel's iridescent textures; on "Blue Line," the pair blend into and timbrally imitate each other.

Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest co-produced Heartcore; it's as unclassifiable as the MC's most intrepid, fusionary works. "This record — it's jazz," Rosenwinkel has said. "And it's much more."

Graham Haynes - Full Circle (2007)

Cornetist, flugelhornist and trumpeter Graham Haynes may be the son of Roy Haynes, who played drums with Bird and Monk and remains one of the final living godfathers of bebop. But if he's ever faced pressure to box himself into his father's aesthetic, he's studiously disregarded it.

Along with saxophone great Steve Coleman, he was instrumental in the M-Base collective, which heralded new modes of creative expression in jazz — a genre tag it tended to reject altogether.

For Haynes, this liberatory spirit led to inspired works like Full Circle. It shows how he moved between electronic and hip-hop spheres with masterly ease, while being beholden to neither. Featuring saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, bassist Shahzad Ismaily, drummer Marcus Gilmore, and other top-flight accompanists, Full Circle is wormholes within wormholes.

Therein, short-circuiting wonders like "1st Quadrant" rub against "Quartet Circle" and "In the Cage of Grouis Bank," which slouch toward ambient, foreboding kosmische.

Craig Taborn - Junk Magic (2004)

Steeped in brutal metal as much as the AACM, the elusive, resplendent pianist Craig Taborn is one of the most cutting-edge practitioners of "creative music." Some of his work resembles jazz, some is uncategorizably far afield.

Strains of electronic music run through Taborn's entire catalog. And his Junk Magic project, which began with his 2004 album of the same name, is a terrific gateway drug to this component of his artistry.

Junk Magic has a haunted toyshop quality; tracks like "Prismatica," "Bodies at Rest and in Motion" and "The Golden Age" thrum with shadowy, esoteric energy.

If these strange sounds resonate with you, 2020's sinewy Compass Confusion — released under the Junk Magic alias — is a logical next step. So is 2019's Golden Valley is Now, an electronics-inflected work of head-spinning propulsion and kineticism.

Flying Lotus - You're Dead! (2014)

Spanning spiritual jazz, devotional music, the avant-garde, and so much more, Alice Coltrane has belatedly gotten her flowers as a musical heavyweight; she and her sainted husband were equal and parallel forces.

Coltrane's grandnephew, Steven Bingley-Ellison — better known as Flying Lotus — inherited her multidimensional purview.

In the late 2000s, the GRAMMY-winning DJ, rapper and producer made waves with envelope-pushing works like Los Angeles; regarding his synthesis of jazz, electronic and hip-hop, 2014's You're Dead marks something of a culmination.

Flying Lotus was in stellar company on You're Dead!, from Kendrick Lamar to Snoop Dogg to Herbie Hancock and beyond; tracks like "Tesla," "Never Catch Me" and "Moment of Hesitation" show that these forms aren't mutually exclusive, but branches of the same tree.

Brad Mehldau - Finding Gabriel (2019)

As per the Big Questions, pianist Brad Mehldau is much like many of us: "I believe in God, but do not identify with any of the monotheistic religions specifically." But this hasn't diluted his searching nature: far from it.

In fact, spirituality has played a primary role in the GRAMMY winner and 13-time nominee's recent work. His 2022 album Jacob's Ladder dealt heavily in Biblical concepts — hence the title — and shot them through with the prog-rock ethos of Yes, Rush and Gentle Giant.

Where Jacob's Ladder is appealingly nerdy and top-heavy, its spiritual successor, 2019's Finding Gabriel, feels rawer and more eye-level, its jagged edges more exposed; Mehldau himself played a dizzying array of instruments, including drums and various synths.

The archetypal imagery is foreboding, as on "The Garden"; the Trump-era commentary is forthright, as on "The Prophet is a Fool." And its sense of harried tension is gorgeously released on the title track.

All this searching and striving required music without guardrails — a marriage of jazz and electronic music, in both styles' boundless reach.

Caroline Davis' Alula - Captivity (2023)

Caroline Davis isn't just an force on the New York scene; she's a consummate conceptualist.

The saxophonist and composer's work spans genres and even media; any given presentation might involve evocative dance, expansive set design, incisive poetry, or flourishing strings. She's spoken of writing music based on tactility and texture, with innovative forms of extended technique.

This perspicuous view has led to a political forthrightness: her Alula project's new album, Captivity, faces down the horrific realities of incarceration and a broken criminal justice system.

Despite the thematic weight, this work of advocacy is never preachy or stilted: it feels teeming and alive. This is a testament not only to jazz's adaptability to strange, squelching electronics, but its matrix of decades-old connections to social justice.

Within these oblong shapes and textures, Davis has a story to tell — one that's life or death.

Jason Moran/BlankFor.ms/Marcus Gilmore - Refract (2023)

At this point, it's self-evident how well these two genres mesh. And pianist Jason Moran and drummer Marcus Gilmore offer another fascinating twist: tape loops.

For a new album, Refract, the pair — who have one GRAMMY and three nominations between them — partnered with the tape loop visionary Tyler Gilmore, a.k.a. BlankFor.ms.

The seed of the project was with BlankFor.ms; producer Sun Chung had broached the idea that he work with leading improvisational minds. In the studio, BlankFor.ms acted on a refractory basis, his loops commenting on, shaping and warping Moran and Gilmore's playing.

As Moran poetically put it in a statement, "I have always longed for an outside force to manipulate my piano song and drag the sound into a cistern filled with soft clay."

The line on jazz is that it's an expression of freedom. But when it comes to chips and filters and oscillators, it can always be a little more unbound.

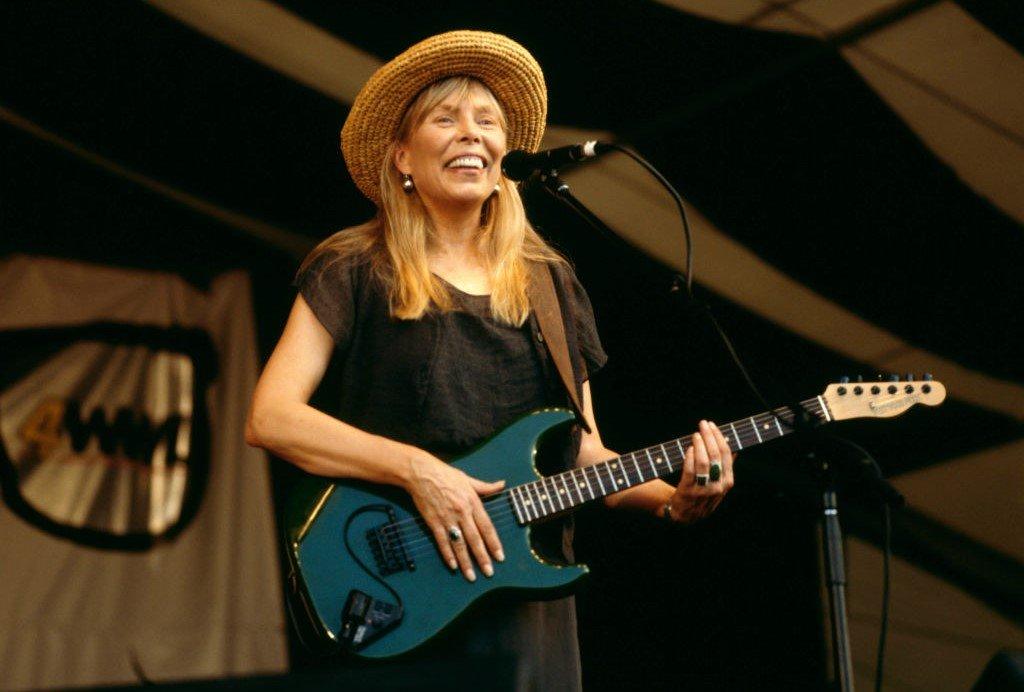

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

list

10 Lesser-Known Joni Mitchell Songs You Need To Hear

In celebration of Joni Mitchell's 80th birthday, here are 10 essential deep cuts from the nine-time GRAMMY winner and MusiCares Person Of The Year.

Having rebounded from a 2015 aneurysm, the nine-time GRAMMY winner and 17-time nominee has made a thrilling and inspiring return to the stage. Many of us have seen the images of Mitchell, enthroned in a mockup of her living room, exuding a regal air, clutching a wolf’s-head cane.

Again, this adulation is apt. But adulation can have a flattening effect, especially for those new to this colossal artist. At the MusiCares Person Of The Year event honoring Mitchell ahead of the 2022 GRAMMYs, concert curators Jon Batiste — and Mitchell ambassador Brandi Carlile — illustrated the breadth of her Miles Davis-esque trajectory, of innovation after innovation.

At the three-hour, star-studded bash, the audience got "The Circle Game" and "Big Yellow Taxi" and the other crowd pleasers. But there were also cuts from Hejira and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Night Ride Home, and other dark horses. There were selections that even eluded this Mitchell fan’s knowledge, like "Urge for Going." Batiste and Carlile did their homework.

But what of the general listening public — do they grasp Mitchell’s multitudes like they might her male peers, like Bob Dylan? Is her album-by-album evolution to be poured over with care and nuance, or is she Blue to you?

Of course, everyone’s entitled to commune with the greats at their own pace. However, if you’re out to plumb Mitchell’s depths beyond a superficial level, her 80th birthday — which falls on Nov. 8 — is the perfect time to get to know this still-underrated singer/songwriter legend better. Here are 10 deeper Mitchell cuts to start that journey, into this woman of heart and mind.

"The Gallery" (Clouds, 1969)

Mitchell blew everyone’s minds when David Crosby discovered her in a small club in South Florida. Her 1968 debut, Song to a Seagull, contains key songs from that initial flashpoint, like "Michael from Mountains" and "The Dawntreader."

Mitchell’s artistic vision truly coalesced on her second album, Clouds. Although the production is a little wan and bare-boned, Clouds contains a handful of all-time classics, including "Chelsea Morning," "The Fiddle and the Drum" and the epochal "Both Sides, Now."

That said, "The Gallery," which kicks off side two, belongs at the top of the heap. There remain rumblings that it’s about Leonard Cohen. But whatever the case, Mitchell’s excoriating burst of a pretentious cad’s bubble ("And now you're flying back this way/ Like some lost homing pigeon/ They've monitored your brain, you say/ And changed you with religion") remains incisive, with a gorgeous melody to boot.

(And, it must be said: "That Song About the Midway," also found on Clouds, is a kiss-off to Croz, whom she enjoyed a fleeting fling with and a must-hear.)

"Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire" (For the Roses, 1972)

If you think you’ve got a grasp of Mitchell’s early talents, a new archival release proves they were more prodigious than you could imagine.

Joni Mitchell Archives, Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975) kicks off with a solo version of "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire." And as great as the studio version is, from 1972’s For the Roses, this version, from a session with Crosby and Graham Nash, arguably eats its lunch.

While Neil Young’s "The Needle and the Damage Done" has proved to be the epochal junkie-warning song of the 1970s, Mitchell’s song about the same subject easily goes toe to toe with it.

Images like "Pawn shops crisscrossed and padlocked/ Corridors spit on prayers and pleas" and "Red water in the bathroom sink/ Fever and the scum brown bowl" are quietly harrowing. Via Mitchell’s acoustic guitar, they’re underpinned by downcast, harmonically teeming blues.

"Sweet Bird" (The Hissing of Summer Lawns, 1975)

The Hissing of Summer Lawns is an unquestionable masterstroke of Mitchell’s fusion era.

Highlights are genuinely everywhere within Lawns — from the swinging and swaying "In France They Kiss on Main Street," to the Dr. Dre-predicting "The Jungle Line," to the title track, a hallucinatory lament for a trophy wife.

But amid these manifold high points, don’t miss "Sweet Bird," the penultimate track on The Hissing of Summer Lawns, tucked between "Harry’s House/Centerpiece" and "Shadows and Light."

"Give me some time/ I feel like I'm losing mine/ Out here on this horizon line," Mitchell sings through her dusky soprano, as the ECM-like atmosphere seems to whirl heavenward. "With the earth spinning/ And the sky forever rushing/ No one knows/ They can never get that close/ Guesses at most."

"A Strange Boy" (Hejira, 1976)

Much like The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira — retroactively, and rightly, canonized as one of Mitchell’s very best albums — is nearly flawless from front to back.

The highs are so high — "Amelia," "Hejira," "Refuge of the Roads" — that almost-as-good tracks might slip through the cracks. "A Strange Boy," about an airline steward with Peter Pan syndrome she briefly linked with.

"He was psychologically astute and severely adolescent at the same time," Mitchell said later. "There was something seductive and charming about his childlike qualities, but I never harbored any illusions about him being my man. He was just a big kid in the end."

As "A Strange Boil" smolders and begins to catch flame, Mitchell delivers the clincher line: "I gave him clothes and jewelry/ I gave him my warm body/ I gave him power over me."

"Otis and Marlena" (Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, 1977)

One of Mitchell’s most challenging and thorny albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is one of Mitchell’s least accessible offerings from her most expressionist era. (Mitchell in blackface on the cover, as a character named Art Nouveau, doesn’t exactly grease the wheels — to put it mildly.)

But across the sprawling and head-scratching tracklisting — which includes a seven-minute percussion interlude, in "The Tenth World" — are certain tunes that belong in the Mitchell time capsule.

One is "Otis and Marlena," one of the funniest and most evocative moments on an album full of strange wonders. Mitchell paints a picture of a cheap vacation scene, rife with "rented girls" and "the grand parades of cellulite" against a "neon-mercury vapor-stained Miami sky."

And the kicker of a chorus juxtaposes this dowdy Floridan outing with the realities up north, e.g. the 1977 Hanafi Siege: "They’ve come for fun and sun," MItchell sings, "while Muslims stick up Washington."

"A Chair in the Sky" (Mingus, 1979)

While Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is rather glowering and unwelcoming, Mingus is a cracked, cubist realm that’s fully inhabitable.

Initially conceived as a collaboration between Mitchell and four-time GRAMMY nominee Charles Mingus, it ended up being a eulogy: Mingus died before the album could be completed.

Despite its lopsided nature — it contains five spoken-word "raps," as well as a true oddity in the eerie, braying "The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" — Mingus remains rewarding almost 45 years later. And the Mingus-composed "A Chair in the Sky," with lyrics by Mitchell, is arguably its apogee.

Like the rest of Hejira, "A Chair in the Sky" features Jaco Pastorius and Wayne Shorter from Weather Report, as well as the one and only Herbie Hancock; this ethereal, ascendant track demonstrates the magic of when this phenomenal ensemble truly gels.

"Moon at the Window" (Wild Things Run Fast, 1982)

In Mitchell’s trajectory, Wild Things Run Fast represents the conclusion of her fusion phase, in favor of a more rock-driven sound — and, with it, the sunset of her second epoch.

Following Wild Things Run Fast would be 1985’s critically panned Dog Eat Dog and 1988’s even more assailed Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm. But for every arguable misstep, like the guitar-squealing "You Dream Flat Tires," there’s a baby that shouldn’t be thrown out with the bathwater.

One is "Chinese Cafe/Unchained Melody," another is "Ladies’ Man," and perhaps best of all is the luminous "Moon at the Window," where bassist/husband Larry Klein and Shorter wrap Mitchell’s sumptuous lyric, and melody, in spun gold.

"Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" (Night Ride Home, 1991)

At the dawn of the grunge era, Mitchell found her way back to her atmospheric best, with the gorgeously written, performed and produced Night Ride Home.

While its follow-up, Turbulent Indigo, won the GRAMMY for Best Pop Album (and is certainly worth savoring), Night Ride Home might have more to offer those who were enraptured by the majestic Hejira, and thirsted for a continuation of its aural universe.

The equally excellent "Come in From the Cold" is the one that has ended up on Mitchell setlists in the 2020s, but "Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" is even more transportive.

Despite the early 1900s sonics, "Passion Play" feels ageless and eternal, tapped into some Jungian collective unconscious as a wizened Mitchell posits, "Who’re you going to get to do your dirty work/ When all the slaves are free?"

"No Apologies" (Taming the Tiger, 1998)

If Night Ride Home sounds less played than conjured Taming the Tiger is like the steam that twists and disperses from its broiling, potent stew.

As much ambience pervaded Night Ride Home, Hejira and the like, Taming the Tiger is the only album in Mitchell’s estimable catalog to feel ambient.

Much of this is owed to Mitchell’s employment of the Roland VG-8 virtual guitar system, which allowed her to change her byzantine guitar tunings at the push of a button; the ensuing sound is a suggestion of a guitar, which enhances Taming the Tiger’s diaphanous and ephemeral feel.

"No Apologies" is something of a centerpiece, where Mitchell sings of war and a dilapidated homeland, sailing forth on a cloud of Greg Liestz’s sonorous lap steel.

"Bad Dreams" (Shine, 2007)

Mitchell has always cast a jaundiced eye at the music industry machine, so it’s no wonder she hasn’t released a new album in 16 years. (Although, as she revealed to Rolling Stone, she’s eyeing a small-ensemble album of standards with her old mates in the jazz scene.)

But if Shine ends up being her swan song, it’d be a fine farewell. "Bad Dreams" — written around a quote from Mitchell’s 3-year-old grandson: "Bad dreams are good / In the great plan" — is impossibly moving.

Therein, Mitchell considers an Edenic tableau as opposed to our modern world, where "these lesions once were lakes." Movingly, the song’s final lines accept reality for what it is ("Who will come to save the day? / Mighty Mouse? Superman?") rather than what she wishes it could be.

With that, Mitchell’s studio discography — as we know it today — reaches its conclusion. But although the artist is only fully getting her flowers today, we’ve only scratched the surface of the gifts she’s bestowed upon us.

Living Legends: Judy Collins On Cats, Joni Mitchell & Spellbound, Her First Album Of All-Original Material

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

list

5 Less-Discussed Miles Davis Albums You Need To Know, From 'Water Babies' To 'We Want Miles'

Despite not being mentioned nearly as much as 'Kind of Blue' or 'Bitches Brew,' these five albums are highly recommended — some for Davis neophytes, some for diehards.

Joe Farnsworth couldn’t believe what he was watching. The leading straight-ahead drummer was sitting with the revered tenor saxophonist George Coleman, and a Miles Davis documentary happened to come on TV.

“This documentary went from Coltrane straight to Sam Rivers,” Farnsworth told LondonJazz News in 2023 — referring to the tenormen the eight-time GRAMMY winner and 32-time nominee employed in his so-called First and Second Great Quintets, respectively.

“What happened to ‘Four’ & More? What happened to My Funny Valentine? What happened to Seven Steps to Heaven?” Farnsworth remembered wondering. “Not a mention, man.”

Granted, Coleman’s tenure represented a transitional period for Davis’s group; his choice of tenorist would solidify in 1964 with the arrival of the 12-time GRAMMY winner and 23-time nominee Wayne Shorter. With pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams as the rhythm section — 18 GRAMMYs between them — the result was one of jazz’s all-time classic groups.

But Farnsworth’s point is well taken: in the recorded canon, jazz tends to lionize the rulebook-shredders and boundary-shatterers, at the expense of merely excellent work. But there’s not only room for both; in order to exist, the former requires the latter, and vice versa.

And given that Davis is, in many respects, the quintessential jazz musician, this wholly applies to him and his formidable discography — where the capital-P pivotal ones, like Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew, get the majority of the ink.

After you check out Seven Steps to Heaven and the like — and absorb Coleman’s important contributions to Davis’s story — take a spin through five more Davis albums that deserve more attention.

Water Babies (rec. 1967-1968, rel. 1976)

Axiomatically, anything Davis’ Second Great Quintet — and keyboardist Chick Corea and bassist Dave Holland, to boot — laid to tape is worth hearing.

But Water Babies should be of interest to any serious Miles fan because it reveals the connective tissue between Davis’ acoustic and electric eras.

The first three tracks, “Water Babies,” “Capricorn” and “Sweet Pea” — Shorter compositions all — were retrieved from the cutting room floor circa 1968’s Nerfiti. (Tellingly, that turned out to be Davis’ final fully acoustic album.)

Tracks four and five — “Two Faced” and “Dual Mr. Tillman Anthony” — add Corea and Holland to the mix; on electric piano, Corea adds a celestial drift to the proceedings. For reasons both

Miles in the Sky (1968)

Miles Davis and George Benson on record? It happened — lucky us. The 10-time GRAMMY-winning, 25-time nominated guitar genius can be found on two tracks from the 1979 outtakes compendium Circle in the Round, and on “Paraphernalia” from Miles in the Sky.

While Water Babies is something of a dark horse for the heads, Miles in the Sky — also featuring the Second Great Quintet —is a fleet, aerodynamic stunner and one of the most unfairly slept-on entries in his discography.

Outside of the Shorter-penned “Paraphernalia,” Miles in the Sky features two Davis tunes in “Stuff” and “Country Son,” and a Williams composition in “Black Comedy.”

It’s sterling stuff, right at the tipping point for fusion — and its obfuscation says nothing about its quality, but speaks volumes as to the volume of masterpieces in Davis’ discography.

Agharta (1965) and Pangaea (1976)

Two primo dispatches from Davis’ experimental years, capturing two concerts from the same evening in Osaka, Agharta and Pangaea are amoebic, undulating wonders.

Across the nearly 100-minute Agharta and 88-minute Pangaea, Davis and company — including alto and soprano saxophonist Sonny Fortune, and guitarists Reggie Lucas and Pate Cosey — conjure everything we expect from electric Miles.

Abstracted drones, worldbeat textures, Davis’ trumpet funneled through twisted wah-wah: check, check, and check. One critic characterized the music as “ambient yet thrashing,” compared it to “Fela Kuti jamming with Can,” and identified hints of Stockhausen, and nailed it on all three counts.

Fans of thick, heavy, electrified Miles typically reach for Bitches Brew or On the Corner first. But if those don’t completely whet your thirst, there’s a whole lot where that came from.

And given that Davis put down the horn, ravaged by illness, for six years afterward, Agharta and Pangaea represent something of a culmination of Davis as the intrepid deconstructionist.

We Want Miles (1982)

Despite what you may have heard, ‘80s Miles — his final full decade on earth, and the one where he drew heavily from pop sounds and songs — is nothing to sniff at.

From 1981’s The Man with the Horn to 1983’s Star People to 1989’s Aura, Davis produced a number of rough-hewn gems. And despite Davis’ bulldozed health during its recording, the live We Want Miles, recorded in ‘81, is among them.

Despite requiring oxygen between songs and wearing a rubber corset to keep playing, Davis is in fine form.

Plus, he’s flanked by heavyweights, from saxophonist Bill Evans (no, not that Bill Evans) to six-time GRAMMY-nominated guitarist Mike Stern and two-time GRAMMY-winning bassist Marcus Miller.

We Want Miles proves that Miles never lost his ability to produce inspired, inspiring work — no matter what his failing body or, erm, ‘80s textures threw at it.

Davis passed away in 1991, and we’ll never see his like again — so savor everything he gave us, whether illuminated or obscured by shadow.

Bird And Diz At 70: Inside Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie's Final Studio Date — An Everlasting Testament To Their Brotherhood

Photo: Meron Menghistab

interview

Cautious Clay's 'Karpeh' Is & Isn't Jazz: "Let Me Completely Deconstruct My Conception Of The Music"

On his Blue Note Records debut 'Karpeh,' Cautious Clay treats jazz not as a genre, but as a philosophy — and uses it as a launchpad for a captivating family story.

Nobody can deny Herbie Hancock is a jazz artist, but jazz cannot box him in. Ditto Quincy Jones; those bona fides are bone deep, but he's changed a dozen other genres.

Cautious Clay doesn't compare himself to those legends. But he readily cites them as lodestars — along with other genre-straddlers of Black American music, like Lionel Richie and Babyface.

Because this is a crucial lens through which to view him: he's jazz at his essence and not jazz at all, depending on how he wishes to express himself.

"I'm not really a jazz artist, but I feel like I have such a deep understanding of it as a songwriter and musician," the artist born Joshua Karpeh tells GRAMMY.com. "It's sort of inseparable from my approach to this album, and to this work with Blue Note."

Karpeh is talking about, well, KARPEH — his debut album for the illustrious label, which dropped in August. In three acts — "The Past Explained," "The Honeymoon of Exploration," and "A Bitter & Sweet Solitude," he casts his personal journey against the backdrop of his family saga.

As Cautious Clay explains, the title is a family name; his grandfather was of the Kru peoples in Liberia. "It's a family of immigrants. It's a family of, obviously, Black Americans," he notes. "I just wanted to give an experience that felt concrete and specific enough — to be able to live inside of something that was a part of my journey."

On KARPEH, Cautious Clay is joined by esteemed Blue Note colleagues: trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, guitarist Julian Lage, and others.

Vocalist Arooj Aftab and bassist Kai Eckhardt — Karpeh's uncle — also enhance the proceedings. The result is another inspired entry from Blue Note's recent resurgence — one lyrically personal and aurally inviting.

Read on for an interview with Cautious Clay about his signing to Blue Note, leveling up his recording approach, and his conception of what jazz is — and isn't.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about signing to Blue Note Records, and the overall road to KARPEH.

I kind of got connected to Don [Was, the president of Blue Note] through a relationship I had with John Mayer, who had, I guess, connected Don to my music.

Don reached out via email probably a year ago, and so we connected over email. And I had sort of been in a situation where I was like, OK, I want to do something different for this next project. We kind of met in the middle and it just made a lot of sense based on just what I wanted to do, and then what they could potentially kind of work with on my end.

So, [I was] just recording the album in six days, and doing a lot of prep work beforehand and getting all these musicians that I really liked to be able to work on it. It was just a really cool process to be able to unpack that with Blue Note.

That's great that you and Mayer go back.

Yeah, man, we have a song. We worked on each other's music a little bit together. The song "Carry Me Away" on his [2021] album [Sob Rock] I actually worked on, and then we did a song together called "Swim Home" that I released back in 2019.

You said you wanted to "do something different." What was the germ of that something?

I felt like it could be interesting to do a more instrumental album, or something that felt a little bit more like a concept album, or more experimental. I wanted to be more experimental in my approach to the music that I love.

I wanted to call it a jazz album, but at the same time I didn't, because I felt like it wasn't; it was more of an experimental album.

But I felt like calling it jazz in my mind kind felt like a free way to express, because I think of jazz much more as a philosophy than necessarily a genre.

So, it was helpful for me in my mind to be able to like, OK, let me completely deconstruct my conception of the music I make and how I can translate that music.

And then it eventually evolved into a story about my family and about American history to a certain extent in the context of my family's journey, and then also just their interpersonal relationships. That sort of made itself clear as I continued to write and I continued to delve deeper into the process.

Not that KARPEH ended up being instrumental. But instrumental records are lodestars for you? I'm sure that blurs with the Blue Note canon.

There's a lot of different stuff. There was that red album that Herbie Hancock released [in 1978, titled Sunlight] that I really liked. "I Thought It Was You" was super inspirational — sonically how they arranged a lot of that record.

Seventies jazz fusion was an overall influence. I felt inspired by the perfect meld of analog synthesizers, and then also obviously organic instruments like horns and guitars of that nature. So I wanted to create something that felt like a contemporary version of what could be a fusion record to a certain extent.

Any specific examples?

Songs like "Glass Face," for example, are pretty fusion-y, but also very just experimental in a way that doesn't feel like jazz, even.

My uncle [Kai Eckhardt] is a pretty big-time bass player, and he played on "Glass Face." I just was like, OK, dude, do your thing, and he just did this sort of chordal bass solo. Then, I did all these harmonies over top of the song.

And then, Arooj Aftab is a really good friend and musical artist; she was able to work off of that as well. So, it was an interesting journey to make a lot of these songs and sort of figure out how they all fit together.

How did you strike that balance between analog and synthesized sounds?

I recorded most of this album at a studio, which is very different for me.

I don't normally do that. I use a lot of found sounds like drums and stuff that I've either made or sampled, but I did all of the drums and bass and upright and electric guitars we'd recorded at a studio called Figure 8 in Brooklyn. That was the backbone for a lot of the music that I created for the album.

Then, I took it back home to my home studio. After we had recorded all of the songs, I essentially had some different analog synths and things that I wanted to add into it either at the studio that I worked at or my own personal studio, which happens to also be eight blocks [away] on the same street away.

I struck a balance just mostly with it in the context of working at a very formal studio and then having an engineer and just getting sounds that I wanted that could be organic and more specific in that way. And also using some of the synths they had.

In terms of the approach, I kind of wanted it to be different. And so part of that was just being at more of a formal studio and having an engineer and overseeing the overall process outside of just being inside of my Ableton session.

Tell me more about the guests on KARPEH.

I knew Immanuel through a couple of mutual friends, and he has a certain sort of bite to his sax playing that I felt was so juxtaposed to my sax playing.

And same with Ambrose. I feel like his trumpet style couldn't be more esoteric and out, in the context of how he approaches melodies. It's almost in some ways like, Whoa, I would never play that way.

They're also soloists, and conceptually for me, the idea of being in isolation or being in bittersweet solitude was conceptually a part of the last part of the album. They as soloists have so much to offer that I feel like I can't do and I don't possess.

So, I wanted to have them a part of this album, to demonstrate that individuality within the context of what it takes to make a song.

Julian is just a beautiful and spirited man, a beautiful guitar player. I've liked his sound for a while. I think it was back in 2015 when I first heard him; he had a couple of videos on YouTube that I thought were just super gorgeous.

I feel like he just has this way of playing that's folky. Also, it's jazz in the context of his virtuosic playing style, but it's also not overbearing. I felt like as a writer and as a musician, it would be a really great connecting point for a few of the more personal songs on the record.

And then my uncle Kai as well, — he's not on Blue Note, but he used to play with John McLaughlin and run bass clinics with Victor Wooten and Marcus Miller back in the early 2000s. Dude is a real heavy hitter, and he happens to be my uncle, so it's just cool to be able to have him on the record.

*Cautious Clay. Photo: Meron Menghistab*

With KARPEH out, where do you want to go from here — perhaps through a Blue Note lens?

I really love a lot of the people there, and I feel like this could be the first of many. It's also a stepping stone for me as an artist.

I feel really connected to the relationship I have, and our ability to put this out. It's hard to say what exactly the future holds, but I am genuinely excited for this album. I feel excited to be able to put out something so personal and so connected to everything that sort of made me, in a very concrete way.

From what I understand, this is a one-time thing, but it could potentially be two. It depends, obviously. I'm very open-minded about it. I'd love to keep the good relationship open and see where things go.

I really have enjoyed the process and I feel like this next year is going to be something interesting. So, we'll see.

On Her New Album, Meshell Ndegeocello Reminds Us "Every Day Is Another Chance"

Photo: Charlie Gross | Illustration: Meshell Ndegeocello and Rebecca Meek

interview

On Her New Album, Meshell Ndegeocello Reminds Us "Every Day Is Another Chance"

"Every morning is a chance to try again, to try to do something different with yourself," Meshell Ndegeocello says. Her clear-eyed new album, 'The Omnichord Real Book,' is charged with a sense of solidarity, groundedness and renewal.

Across the decades, Meshell Ndegeocello has worked with many consequential jazz figures: she's voyaged with Herbie Hancock, fed the fire with Geri Allen and soul-danced with Joshua Redman.

But her music has a beating pop heart — and not just because she's also collaborated with Madonna, Chaka Khan and the Rolling Stones. Accordingly, she's fully aware of pop's inherent power and limitations.

"I love pop music, but I didn't want to entice people with a turn of phrase," the GRAMMY-winning bassist, multi-instrumentalist, singer, songwriter, and composer says of her new album, The Omnichord Real Book. "I wanted them to hear something that is: wake up, return, balance, align."

The Omnichord Real Book is Ndegeocello's first album of original material in nearly a decade and her debut on Blue Note Records. True to her stature in jazz and jazz-adjacent spaces, Ndegeocello is joined by some of their best and brightest: pianist Jason Moran, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, harpist Brandee Younger, and many others appear in its grooves.

But Ndegeocello has evaded categories from the jump, and "jazz" can't box her in. Midway through the interview, she stresses that the high-profile guests weren't "curated" for cred. Ndegeocello even announces that she'd like to collaborate with Taylor Swift.

Like its creator, The Omnichord Real Book is a Pandora's box. The title refers to the electronic instrument, which she took to during lockdown. The African diaspora runs through songs like "Georgia Ave" and "Omnipuss." The passing of both her parents formed the album's wounded center — but also its sense of overcoming, and starting over.

As you listen, read on for an interview with Ndegeocello about the state of her musical thinking, her blossoming capacity for collaboration and why it's important to "cherish your voice — your uniqueness, your touch."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

This is your first collection of original music in some time. Draw a thread for our readers through the past decade of your life and creative output.

To be honest, it was the downtime of the pandemic that allowed me to hear my thoughts again — hear the music in my head.

It was that downtime that also kickstarted my TV and film scoring. So I was spending seven to eight hours on a computer a day. And so at the end of the day, after making dinner for the family, I yearned for music, but I found myself playing with my omnichord — just anything without a screen. My Casio keyboard, or basses and guitars.

I just wanted to escape that looking at music, you know? I'm looking at waves; I'm looking at a screen. And so a lot of the writing just came from that. Being alone, being by myself — having beginner's mind, so to speak.

I've been on computers since I was a child. I wish I didn't have to use one anymore.

Even doing Zoom is hard. I have a landline. I wish we could just call and talk on the phone. But it's not because I'm nostalgic; I want to make that clear. I'm not nostalgic, I'm not pastiche, and I'm not a grumpy old person. I love technology — oh my god.

But just for me at that moment, I wanted to get back to the mysticism of sound. How your ears can be a time machine. When you hear a certain song from your childhood, it transports you.

And I don't think it's because you see the videos, it's because you hear something in it. It touches something in your brain that creates all that chemical reaction that you feel, see and smell where you were at that time. And that's what I'm really into now. I think the sound waves are powerful, and I'm trying to disconnect my visual senses from that experience now.

One of my favorite bits of jazz lore is that Wes Montgomery learned to do what he did by just sitting there with a guitar and Charlie Christian on the turntable. That extends to most of the 20th century. Can you connect that to the mystical, ineffable stuff of music?

Oh, exactly. Ineffable. I mean, I too sat with the Prince records and just learned them — and the Parliament-Funkadelic records, and the Sting records, and the Howard Jones records, and the Thomas Dolby records, who was sort of the first beta tech person to me in music. Scritti Politti and Thomas Dolby.

What I mean by the mysticism is: I found myself listening to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan a lot during the pandemic. I found myself listening to George Russell during the pandemic. Stanley Turrentine, these sorts of analog gems.

Wayne Shorter and Steve Coleman showed me that there's something mystical in the rhythms and the harmonies that they can create that are beyond comprehension, that have no technology involved. It's just in their writing and composition.

That's what I mean: where you could hear something and it just blows your mind. How did they get there melodically? How did they get there rhythmically? And I just long for that now.

It's really about the person — what you do with it. And so lately with Logic, speaking of that, I keep my screen black and white. And when I find myself on playbacks, I turn it off or walk away. I just try to engage with it differently.

I really enjoy just listening again. Taking a walk and letting my aural senses entice me instead of constantly having my eyes determine what I feel or what I see. And maybe that edit's not right. Is the bass flamming? I don't know if it feels good, I leave it. Just sort of letting go of the visual aspect of production.

With that established, where did the Omnichord Real Book songs come from? What did you want them to spiritually transmit?

I must admit I'm a little nervous about talking about my faith and spirituality. I guess during COVID there was a lot of death, and just a lot of emptiness, and an inability to engage sorrow. And so I think in this record you hear that a little bit.

After all the songs were written, it was super important to me for us all to be in the studio together. And that's what I wanted to come across. I am the songwriter, I do come up with the ideas, but it's the people that give it life, and give it limbs, and different hues, and just different ways of self-expression.

I paid for this record myself. I made it and then let Blue Note hear it. So it's pretty much all of what I wanted to have come to fruition. And so it's just all about playing together. It's about singing in a group.

If you notice, there's a lot of group vocals. I think there's a reason we have choirs or the reason people gravitate to spaces that have a lot of people who are collectively trying to be at peace. And so I hope that comes through there.

The songs are simple — just little poetry elements. I love pop music, but I didn't want to entice people with a turn of phrase. I wanted them to hear something that is: wake up, return, balance, align.

Every morning is a chance to try again, to try to do something different with yourself, to try to feel different, to try to engage your partner and wife different. Every day is another chance. And I think that's what I'm trying to show in the album.

Can you talk about your version of Samora Pinderhughes' "Gatsby"? That seems to be a lynchpin to the album.

When my father passed, my mother passed, I had to clean out their house. I found my old Real Book that my father gave me just so I could get through the gigs with him. He had lost a bass player. That book allows five or more people to get together and concentrate on one song and play together if they don't know each other, and it's got to be a quick sort of gel.

[With] Samora's song — or "Hole in the Bucket," written by Justin Hicks — I want to aid in the new standards, the new songs that maybe we'll look back on. I think Samora's lyric is brilliant in Gatsby. It's a time, it's an old story that's been here. What does it gain you to have the whole world and lose your soul? So yeah, I think that's going through there.

I'm at an age now where it's important to be upfront. It's not so important to be the main voice. And I want to show that as we pass through time, the gift you can give is just to big up other people, bring them along to help put them in the position so that they can play more.

Like Joshua Johnson, and Hannah Benn, who I think is a genius — I want everyone to know her. The HawtPlates. It's like, I just want to take this opportunity to put music in the world that feels good, brings about new energy, and showcases new talent.

**There are so many titanic musicians in the scene to choose from. How did you curate who'd appear on The Omnichord Real Book?**

My social skills were lacking during my early 20s. And on top of that, I had a record deal and I was traveling, so my sense of self was a little off. But I'm happy I went through that. And I was raised by musicians who were competitive — sort of real jazz, that jazz mentality of like, I'm going to tear you down to build you up.

But as I aged, and as a woman, I realized that energy just wasn't really the energy I wanted to have. So when you speak of the guests, it's just I think a testament to my growth as a human being and that I'm not as shy and insecure. And I really, if I meet someone and I love their playing, I'm asking them for their number, I'm going to text them, I'm going to ask them about their life and try to create some sort of rapport with them. So, these are just people I've been blessed to meet.

If anything, I'm not curating. That word hurts me. I'm in the sense, I want to be, kind of create collectives, like Don Cherry or something. I'm trying to just get everyone involved because that's the beauty of music and probably why I didn't become a painter.

Painting and visual arts is lonely. It's a lonely thing. But once I learned that, wow, we're all together in this music thing, it definitely inspired me to want to be more about the music. It's like that's the best part to me, that we all can get together and interact.

Can you talk about the role of the vocalist Thandiswa Mazwai on The Omnichord Real Book?

She was on one of my previous records, [2007's] The World Has Made Me the Man of My Dreams. South African singer. Miriam Makeba anointed her. I just find her melodic and rhythmic sense amazing.

I am African American. I am not African. And to quote my brother [trumpeter] Nicholas Payton, I play Black American music. So, I think the participation was, again, just friendship and camaraderie.

But the song ["Vuma"]— what she's talking about is vuma; is that vuma is the voice. And not only the voice of projection, and singing, or speaking, but the tone you have as a writer, as a musician, as a bassist.

We talk about the touch, the tone, the vuma. That's what we're trying to convey in that song. Not about perfection, or pitch. It's the way that you carry yourself and protect that voice, so that individuality, it's you — that you have a self.

I feel so many people want to sound, or feel, or experience like another. I think Thandiswa and I are just trying to remind you to cherish your voice — your uniqueness, your touch, your harmonic sense; your melodic, carefree ideas.

Don't try to pigeonhole yourself in order to be successful. Just say it a little bit for yourself when you can. I think that's what we're trying to say.

What's the state of your bass thinking — in conjunction with your compositional thinking, or instrumental thinking? Which point in your evolution are you in?

In terms of bass playing, I don't play the same; I don't hear the same. So, it's my love instrument. It is like my appendage, so I don't allow other people to question it. So I feel really secure in my bass playing, and with myself as a bassist.

As a songwriter, I'm just still hoping to grow. I want to create some more complex music, more complex instrumental music. And I'm blessed to say I'm getting asked to work with artists that I really admire.

I'm about to work with [saxophonist] Immanuel Wilkins in the so-called producer chair. But yeah, I want to work on arrangements and use the other parts of my brain. And find other artists that want to work with me as well.

So, that's where I am now. I'm here to serve. How can I be of service as a human, as a parent, as a friend, as a musician?

We Pass The Ball To Other Ages: Inside Blue Note's Creative Resurgence In The 2020s