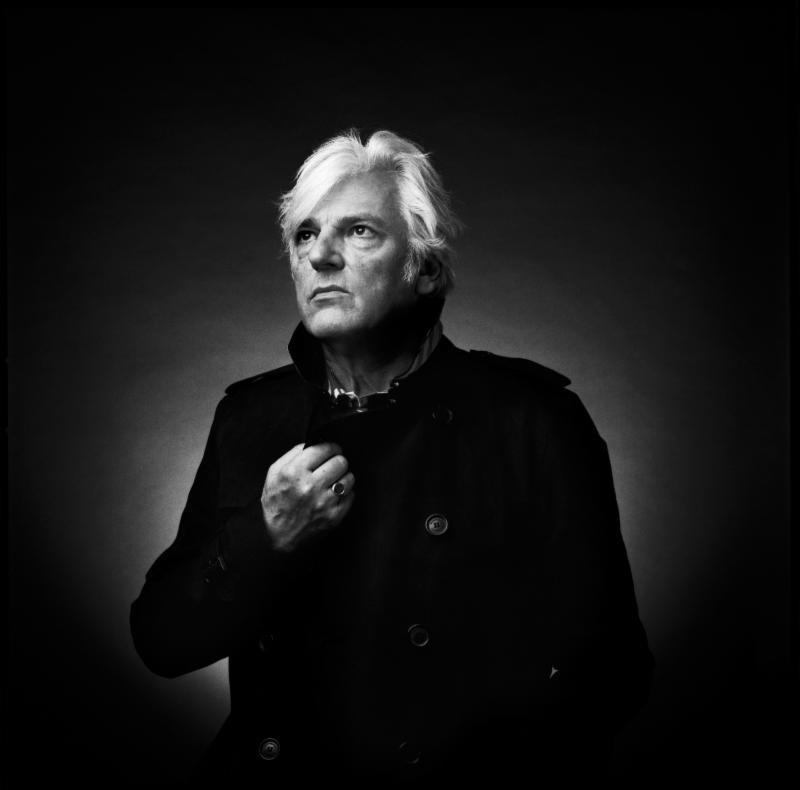

Chances are, you've never met anyone quite like Robyn Hitchcock. The beloved British singer/songwriter has spent the better part of the last five decades earning a sort of self-adjudicated PhD in all things rock and roll, poetry, folk, America, philosophy, the human condition, psychedelia and, of course, the Beatles.

"If there was a genre called 'Beatles music' rather than called '60s pop or psychedelia or something, that would be what I play," Hitchcock said. "There are other influences there, but the harmonies, the guitars, the tempos, the sounds, essentially, in my head anyways, [come from the Beatles]."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/lZErRsTnW5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

But don't let Hitchcock's reverence for the Fab Four fool you – he's one of the most imaginitive and original artists of his generation, which is saying a lot for someone who came up in the hotbed of '60s rock. From his early–and highly influential–work with the Soft Boys in the mid-'70s to his impressive catalog of 21 albums, either solo or backed by incredible bands such as the Egyptians and the Venus 3, Hitchcock has consistently released records that inspire the imagination, delight the ear and defy the norm.

These days, Hitchcock calls Music City, U.S.A. home, and plays with the aptly named Nashville Fabs. He's also recently diversified his psychedelc folk portfolio, penning the haunting number "Sunday Never Comes" for the remarkable Rose Byrne and Ethan Hawke 2018 movie Juliet, Naked, and releasing a new collaboration EP with XTC's Andy Partridge just a few months ago titled Planet England.

The Recording Academy had the surreal honor of speaking with Hitchcock over the phone from his home in Nasvhille to hear about his ongoing project with Partridge, his love for the Beatles debates, John Lennon's looming legacy, and why what he's working on next is keeping him "incrediby busy."

By moving to Nashville, you bring an eclectic flair to its ever-widening creative scene. But what has living there brought to your life?

Well, it's brought great people to play music with. And you can also get anywhere in the bloodstream of the United States and Canada, anywhere east of the Rockies in about two hours by plane, which is fantastic. It's a very good place to tour from. Touring the States is my job, it's what I do for a living.

But I think all of the recent recordings I've done have been here with other people based in Nashville, and it's a joy that a great bunch of people just come around and run through songs in your living room. And then you find some other place to play, and then you can do a show or make the record. I haven't been in a community, such as small local, specific community of people all engaged in the same thing, since I was at what y'all call high school in my teens.

I see, regularly, people that do the same thing as me, and that I work with and play with. There was a little bit of that in the Soft Boy days in Cambridge, which was another small scene, but [Nashville] is bigger than that, much more professional. Very few musicians make it out of Cambridge alive. And Cambridge, U.K., it tends to kind of eat its own sons and daughters. But Nashville, it's a great hive. People are swarming, taking off and landing and get to the airport and it says, "Welcome to music city!" I love that element. It is great.

Being surrounded by songwriters like that, has it changed your writing process?

No. No, not at all. I haven't done that thing of getting into a cage with another songwriter and trying to co-write. Nashville wears a Stetson for publicity purposes, but all kinds of music goes on here. I think the commercial end of it is still quite country-ish. And my connection to country music really doesn't go any further than "Sweetheart Of The Rodeo" by the Byrds, which I love and gave me a crash course in some elements of country, but it doesn't influence me on the whole. Every so often I'll come up with a kind of pastiche country song, but I don't have to be in Nashville to do that. I think the last one I wrote, my last faux country song was written in Norway and probably the one before that, I was living in London. Being out here hasn't made me any more twangy.

"Nashville wears a Stetson for publicity purposes, but all kinds of music goes on here." -Robyn Hitchcock

Yes, I thought I heard it for a couple notes of twang on your new EP with Andy Partridge, Planet England, but I was mistaken. Maybe I was looking a little too hard for the Nashville influence, but I'd love to ask you about that project, too. You've said it could have been made any time in the past 53 years. Why was now the time for you and Andy to do this together?

I think because of the stage in our life cycles that we're at. We actually wrote those songs and did the basic recordings 12 years ago. We were in our early-to-mid-50s, but we didn't finish it off until last year for a whole variety of reasons.

I think Andy and I probably were quite suspicious of each other when we were young indie rockers, and then we were kind of both on the alternative charts in the States in the 1980s. By the time we were over 50, I think we were kind of able to approach each other really. Now we're heading into our late 60s. I go around to his house in Swindon when I'm back in Britain, which is fairly often. It's just down the road from my sister. So I could easily see a day's gone where I can meet him in Swindon and get back to Bath. And I've got country roots anyway, so you know, it's my parallel life. It's two old psychedelic pensioners rocking away in a shed in a back garden. It's just everything that Americans probably dream of, these quaint little Brits in some damp shed in a backyard with primitive equipment.

But actually Andy has the equivalent of the entire firepower of Abbey Road's Studio One in his shed and has always maintained it completely state-of the-art sonic libraries. So he's capable of summoning out any kind of sound that we want for our proto-psychedelic music. We're two guys who had been 17 when the Beatles broke up, still looking for that missing Beatles album. And so we're sort of basically trying to make it ourselves. I mean both of our careers have been that to some extent. And we think that the Dukes of Stratosphear [Partridge's band] really nudged it.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/su_fep2iARQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

When I make a rock record or I play with a band, it's always some kind of basically playing Beatles music, and there are other influences there, but the harmonies, the guitars, the tempos, the sounds, essentially, in my head anyways is just kind of- If there was a genre called "Beatles music" rather than called '60s pop or psychedelia or something, that would be what I play and largely what Andy plays and, As we're getting the arc of our careers, we're getting to the point where that's what we really like making. So fingers crossed, two songs into another project and I'm supposed to see him in Britain at the end of next month so we'll see what we can do.

The Beatle gene runs deep…

Well you know, again, it's what people have in common. I've got this show tomorrow night with my band the Nashville Fabs. They're all Beatles freaks, and we do a ton of Beatles encores with guest singers, and I'm doing one. Everyone just disappears into the corner of their own mind trying to work out whether something is a major-seventh or a relative minor-third. Is it a minor-sixth or is it actually a seventh of the relative-fourth? I mean, it's fantastic watching people debating and playing. Now they've all got the Beatles on their phones, and they just sort of hold the phone up to the microphone, and we can all hear this transistor radio sound, on whatever it is, "You Won't See Me," or something. "I think it's a minor-" "No, it's not actually, it's-" "Oh, gosh, they're singing a D over B or is it a B over D?" You know, nobody's ever completely sure. I love that, they get excited about defining it.

Yeah, it's like one, big, first chord of "Hard Day's Night." Everybody's going to be debating what it is until the end of time.

It is! It's the library in Alexandria that the Romans burnt down, the repository of all human knowledge, hanging on the first chord of "Hard Day's Night."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/lGJOAiWK4q0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Well, we're coming up on the anniversary of John Lennon's death [Dec. 8, 1980]. I thought maybe you could say something about what John, specifically, meant to you.

John Lennon, to myself and probably millions of other kids, including probably Andy Partridge, was a sort of an elder brother, you know, he was the cool, daring, kick-ass, wise-but-foolhardy older brother, the one who took the risks, the one who went out and got hit, the one who challenged authority, but also the one who had success, you know, the trappings of success. You could think, "Oh wow, John Lennon's got a house. John Lennon's got a plane. John Lennon's got a beautiful wife. John Lennon's got a drug habit. John Lennon's paranoid. John Lennon's beautiful. John Lennon's falling out with Paul McCartney. You can look at anyone you admire and the way they are on a pedestal, you can never be them. In another way, they're just like you, if somebody's too alien, they're very hard to kind of connect with, you know?

And I think there's that thing about idols with feet of clay. I think people do want a vulnerable hero, and John was just that. He was vulnerable, and in the end he was killed. How's vulnerable is that? It was awful. I am still grieving Joan Lennon much more than I grieve my parents. And you know both of them lived a natural lifespan. I mean there's so much now for John Lennon to live up to, that if he came back, he couldn't. Since he's died, he's been the good cop. McCartney's had to be the bad guy because he lived on. It's been "St. John" for nearly 40 years and you know, he obviously wasn't.

But he, as Richard Lester [director of 'Hard Day's Night' and 'How I Won The War,' both featuring Lennon] said, he made you care about him. I think he's a real emotional touchstone. The Beatles always make me feel very human. A lot of people I like, Captain Beefheart or Syd Barrett, they're kind of elsewhere, or David Bowie, there is more of a kind of, "I'm outside of this human orbit. I'm not down there in the mud with you lot. I'm somewhere apart." And Bob Dylan, you know, they're kind of insightful, mythical creatures on the edges of things. The Beatles are right in the center, and John was right in the center of the Beatles. And then he couldn't keep it together, couldn't keep up with Paul, who was actually probably tougher than him, but didn't get the knocks. John was the ice-breaker, he was the one who started it, but also [got knocked].

But I also don't think John was better than Paul, you know. I think it works because they were so evenly matched. And then George, became as evenly matched as them, and it was too much, a mouth with too many teeth in it, time for them all to leave home. But the tension on that journey is sort of, John starting it, and then Paul coming up, and then George coming up – what that did to them still produced incredible records. I love the Beatles. Really. Lennon could rubbish the myth all he wanted. It doesn't really matter what you are, it's what people think you are, especially once you've gone. It was for him to demolish the Beatles, but even he couldn't really, the myth is as strong as ever. And you know, as you can see, I have a lot to say about John Lennon.

Indeed. It's a tough time every year when this anniversary comes around to remember that loss.

It's awful and I feel for Yoko [Ono], and Julian [Lennon], and Sean [Lennon] because it's a personal loss for them. And for the rest of us, we're all sort of projecting, a person we never knew but had a relationship with.

Absolutely. I also want to ask you about "Sunday Never Comes," specifically the new video you've made, which leaves you with a very beautiful and disconnected feeling, much the way the song does. You wrote it for a film, but how did it feel to have the song survive that process, and kind of come back to you in this way with the video?

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/LIMpGGDMAmo' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

We deliberately decided to do a proper recording of it because the only thing that was out was my demo for the Juliet, Naked movie, and I really liked the way Ethan Hawke sang it, but I wanted to see what it'd be like if I did it properly. So I recorded it with the Nashville Fabs, and then our friend Jeremy [Dylan] actually did that video. He was our roommate for a while, and he very sweetly makes these videos for us. He made that in Sydney. My partner Emma Swift, who sings with me sometimes and is working on her first full-length record here in Nashville – in fact we're doing some recording in LA next week – Emma's in there as my kind of- I'm this artist in an abandoned apartment somewhere. Nobody's decorated since the 1960s. Somehow the electricity is still connected, and I'm watching obsolete programs on dead televisions, and then Emma appears, my muse, but I can't get at her. She's somewhere else across the world looking desolate.

Most of my videos have always had some humor in them. I don't like taking things that seriously, I guess. I just think there's always got to be a laugh in there somewhere, or it's- Life is pretty unbearable [laughs]. And this one, we didn't put any jokes in. There's nothing funny in there at all. It's just me. I start drawing her at one point, and then I see her on the telly, but it's very unresolved. Sunday never comes, and Emma never turns up, whatever Emma represents, my enigma, my muse. But it's quite a sad one for me, but I'm sure whatever I do next will be a million laughs. [laughs]

Well, you latest LP [2017's self-titled album] was not only your 21st album, it was one of your best. What are you working on next? What are your goals and interests these days?

Well, whatever I put out, if I put out a 22nd one, I want it to be as good as the 21st. So right now I'm rather avoiding that by working with Andy and working on Emma's record, and whatever I've actually written. I never write the songs that I want to write. I write the songs that appear. "Sunday Never Comes" was a commission. But even then I didn't know what I was going to write. They just said, "Write a Robyn Hitchcock song." So that's what popped up. So what I've got lying around or what I'm working on is a collection of piano songs, rather somber piano songs. And I guess when Emma's record is done, because I'm part of that, I'm part of the hive mind working on that, guitar and arrangements. And once Andy and I are well into the Partridge record, hopefully next year, I will start recording these piano songs.

"I never write the songs that I want to write. I write the songs that appear." - Robyn Hitchcock

I bought a four-track cassette machine and a reel-to-reel. I want to do it on hissy, compressed tape with tape delay so it sounds like something that was done years ago. I mean, I know Elliott Smith was doing it 20 years ago, there's nothing new about retro sounding. But kind of how I used to take demos in the 1980s, I want to kind of get a sound that's all my own before I bring anyone else in. And then, you know, it might be a long time before anything comes out, but I'm totally working on it. And I've got lots of other projects, visual stuff. I'm supposed to be doing some paintings, and I'm got a collection of lyrics with illustrations. That's probably going to be the next thing to be "on sale," if you like.

So I'm incredibly busy. You wouldn't think so, but actually there's a hell of a lot going on. Plus, I play a hundred cities a year and I have to get to them all. So I've got L.A., Chicago, New York before New Year's and then it all starts up again.

Robyn Hitchcock will be playing at Largo at the Coronet in Los Angeles on Friday, Dec. 13, and tickets are available here.

WATCH: Robyn Hitchcock Talks With Portia Sabin About Touring, Songwriting, Rock & Roll And More...