Photo: Gus Stewart/Getty Images

feature

Lou Reed's 'Berlin' Is One Of Rock's Darkest Albums. So Why Does It Sound Like So Much Fun?

Lou Reed's third album is a harrowing examination of addiction, abuse and suicide. Yet the bleakness lands because it's so beautifully counterweighted.

Lou Reed's Berlin begins with a nightmarishly tape-destroyed German count-in — eins, zwei, drei, zugabe — followed by the "Happy Birthday" song. It ends with a bloody suicide in a bed.

Wait, that's the second-to-last track; Berlin actually ends as the narrator callously brushes off said suicide — which happened to be of the mother of his children. The lynchpin track, "The Kids," features a harrowing soundbite of children screaming for their mother.

In between, Reed relates the tale of a relationship that spins out into addiction, prostitution and domestic abuse against the backdrop of the titular city — which, at the time, Reed had never been to.

Berlin profoundly alienated some critics. Rolling Stone castigated it as one of "certain records so patently offensive that one wishes to take some kind of physical vengeance on the artists that perpetrate them...a distorted and degenerate demimonde of paranoia, schizophrenia, degradation, pill-induced violence and suicide."

Likewise, Robert Christgau called the notion of Berlin's artistic accomplishment "horses—" and added that the story of the couple "lousy," with the ambitious, operatic music "only competent." By all accounts, the incomprehension hurt Reed; he pulled a 180 with 1974's glammy Sally Can't Dance.

But despite the content, and the chaos in Reed's personal life at the time — fathoms of drugs, a failing marriage — Berlin is no druggie disaster. In reality, it's one of the crown jewels of the GRAMMY winner's voluminous discography, and a masterclass in finding beauty in the sordid depths of the human condition.

And it's difficult to imagine Berlin's story landing without utterly gonzo music — and a fair amount of ink-black humor.

The key to the former is the GRAMMY-nominated producer Bob Ezrin, who's helped craft any number of epic, ridiculous, fall-on-your-face rock classics. Case in point: a year prior to Berlin, he'd produced Alice Cooper's School's Out; just after, he'd helm Aerosmith's Get Your Wings.

Berlin followed 1972's Transformer — his second album and breakthrough, by way of the epochal "Walk on the Wild Side." Both the album and single's successes were helped along by a very high-profile producer — an ascendant David Bowie.

But as Anthony DeCurtis lays out in his 2017 biography Lou Reed: A Life, Bowie had been attracting credit for Transformer, and Reed started to look like his imitator.

"From the industry perspective, the aesthetic differences between Bowie, Reed and Cooper were meaningless," DeCurtis explains in the book. "Broadly speaking, they were all working the same side of the street — bending gender categories and stunning conventional sensibilities."

Given this perception — and a brawl they'd undergone in a London club over Reed's habits — it was time for Reed to untether from Bowie, just as the latter launched into the stratosphere.

"Lou is out of the glitter thing. He really denounces it," crowed Reed's manager at the time, Dennis Katz. "He's not interested in glam rock or glitter rock. Lou Reed is a rock and roller." Reed and Katz went with the 23-year-old Ezrin, who was riding high on Alice Cooper's success — and seemed like the obvious choice.

With the success of Transformer in the rearview, Ezrin and Reed felt emboldened to devise a work of boundless aspiration. It would be a rock opera — a double concept album with an elaborate booklet, with photographs that depict the downfall of the central couple, Caroline and Jim.

Ezrin booked a wild backing ensemble — including keyboardist Steve Winwood of the Spencer Davis Group, Blind Faith and Traffic; bassist Jack Bruce of Cream; drummer B.J. Wilson of Procol Harum; and Michael and Randy Brecker, respectively on tenor sax and trumpet. As the sessions rolled on, hype broiled around the project.

"It's not an overstatement to say that Berlin will be the Sgt. Pepper of the seventies," blustered Larry "Ratso" Sloman in Rolling Stone. Which is laughable today — but it helps frame Berlin in its time and context.

"When people thought of a concept album, they thought Sgt. Pepper," singer/songwriter Elliott Murphy, who befriended Reed around this period, tells GRAMMY.com. "And Berlin is kind of the Antichrist of Sgt. Pepper."

Just as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band used childhood and nostalgia as a launching pad rather than a set of rigid parameters, Berlin — which ended up being a single-disc release — doesn't simply bludgeon you with misery for 49 minutes.

Berlin takes flower from its title track, a barely-there sketch of a romantic scene in the titular city, originally released on Reed's self-titled 1972 debut. As DeCurtis opines in Lou Reed: A Life, "Perhaps it was the song's unfinished quality that appealed to them, leaving space for them to fill with their fantasies of what it might become."

Whatever the case, Reed had a natural facility for expansive narratives. As author Will Hermes explains, Reed's early "mentor and model" was Delmore Schwartz, his English professor at Syracuse University.

"There's humor and there's pathos in equal parts," says Hermes, whose sprawling, fascinating biography, Lou Reed: The King of New York, was released Oct. 3. He's referring to Schwartz and his work, but this extends to his mentee: "Reed was a hilarious guy, from everybody I spoke to, and certainly reading his interviews. So that darkness and humor came together. I don't think a lot of people got that about Berlin when it was first produced."

Reed had taken a theater class at Syracuse, loved Federico Fellini in college, and remained a cinephile for life. By its very nature, the episodic, operatic format of Berlin precludes monotony; each song examines this doomed coupling from a different angle.

Sure, every facet of the Berlin tale is cursed. But Reed explains why it's cursed — including from Jim and Caroline's warring perspectives, as on "Jim Says," "Caroline I" and "II" and beyond. Which gives it innate narrative variety, as the listener ping-pongs through the sordid tale.

"'The Bed' and 'The Kids' are very powerful experiences, but not really a hoot," Stickles says of Berlin's B-side. "But the A-side is a pretty big hoot. Like, 'Caroline Says I' rocks. 'How Do You Think It Feels' — these are fun, big rockers, and it's got the funny flutes and clarinets as well."

And while Reed is unflinching in his depictions of violence and suffering, that quality doesn't render him a bore on Berlin — Reed being Reed, it makes him a live wire.

"Berlin is not that one-dimensional; it's not a single-note record," singer/songwriter and Reed head Jerry David DeCicca, who's just released his latest album New Shadows, tells GRAMMY.com. "It might be shades of some of those things, but that's what makes it interesting."

This eclecticism extends to the music, which never rolls over and cries in its milk, but frequently detonates with goofy, stadium-sized, Meat Loaf-esque jubilance. But despite its pedigree and context within a specific chapter of hard rock, Berlin sounds oddly singular.

Patrick Stickles, the lead singer of the rock band Titus Andronicus and a Reed acolyte, calls Berlin "far more proggy than your typical Lou Reed material."

"It's very ornate, but it doesn't really sound like Yes or King Crimson or whatever was going on at that time," Stickles tells GRAMMY.com," because he's still writing with his favorite two or three chords."

"It just doesn't sound like a lot of records from that time period," DeCicca says. "So I don't think he was trying to fit in."

DeCicca then considers the wider scope of Reed's catalog: "He made another record after that, the next year, that was just incredibly different [Sally Can’t Dance]. Which I'm sure was in some part a reaction to it. But how conscious or unconscious is probably a little bit debatable. I mean, he was not somebody who wanted to repeat himself."

In the end, Berlin resonates due to Reed's boundless audacity — and the sheer oddness that permeates its grooves, from start to finish.

"That's probably his No. 1 virtue as a writer — that he always goes there," GRAMMY nominee Will Sheff, who's struck out solo after two decades fronting Okkervil River, tells GRAMMY.com. "I think his main innovation is that he took the guardrails off of subject matter." (Tonalities, too: whether this was intentional or not, Sheff calls 1967's The Velvet Underground & Nico "one of the most f—ed up, cheap, amateurish things that you've ever heard.")

Sheff and his Okkervil River bandmates clung to Berlin during desperate, ragged tours of yore: today, he marvels at the contradictions of its studio dynamic.

"Based on a lot of the accounts, it sounds a little bit like Bob Ezrin was kind of dragging him through the process of making it," Sheff says. "It kind of sounds like a f—ed up, surly, stuck in molasses guy, who's being sort of dragged out of bed and forced into the studio, where there's a string section waiting for him."

(Was Reed on fire in the studio, or being "dragged" by Ezrin? "I think it was a bit of both," Hermes says. "There were a lot of drugs and alcohol involved, but they were working really hard, being really ambitious.")

However checked out Reed was or wasn't, Ezrin brought his consummate showmanship to the party. "And that's part of what makes Berlin fun — he really honors Lou Reed's ambitions, maybe more than Lou was honoring them at the time. I wouldn't call it joyous, but there is a lot very butch [energy], like, 'I'm just a guy strutting down the street in Berlin, and I'm a tough man.' I find that stuff very charming."

Sure, Berlin may be exactly how Sheff describes it: "excessively dark…sick, diseased, kind of broken heart of a masculine anger and sorrow." Against that pitch-black backdrop, every overenthusiastic drumfill, expensive string flourish and brutal joke truly sparkle. (As per the latter: ("This is a bum trip," Caroline complains about domestic battery.)

Despite the sting of critical rejection, Reed continued pursuing long-form, narrative works throughout his career. These included what Hermes calls "three experimental quote-unquote musical theater pieces.") These were with the visionary Robert Wilson — one based on H.G. Wells' The Time Machine, another based on Edgar Allen Poe, and another in Lulu, which germinated into a polarizing 2011 album of the same name with Metallica.

And Reed always felt strongly about Berlin. In 2006, he revived it for a stage show, which would be released two years later as Berlin: Live at St. Ann's Warehouse. As Hermes put it, "The performance was frequently gorgeous and a bitter pill: magnificent, overwrought, pretentious, full of thematic misogyny." In other words, it's a lot — and it deals in far more than you-know-what quality.

"Lots of content in life is depressing," DeCicca says, "but that doesn't mean you write off people's experiences as not being worth engaging with."

Half a century on, Berlin isn't merely worth engaging with — it remains brazen and captivating, a looking glass into the heart of darkness.

Living Legends: John Cale On How His Velvet Underground Days & Love Of Hip-Hop Influenced New Album Mercy

Photo: Mike Miller

interview

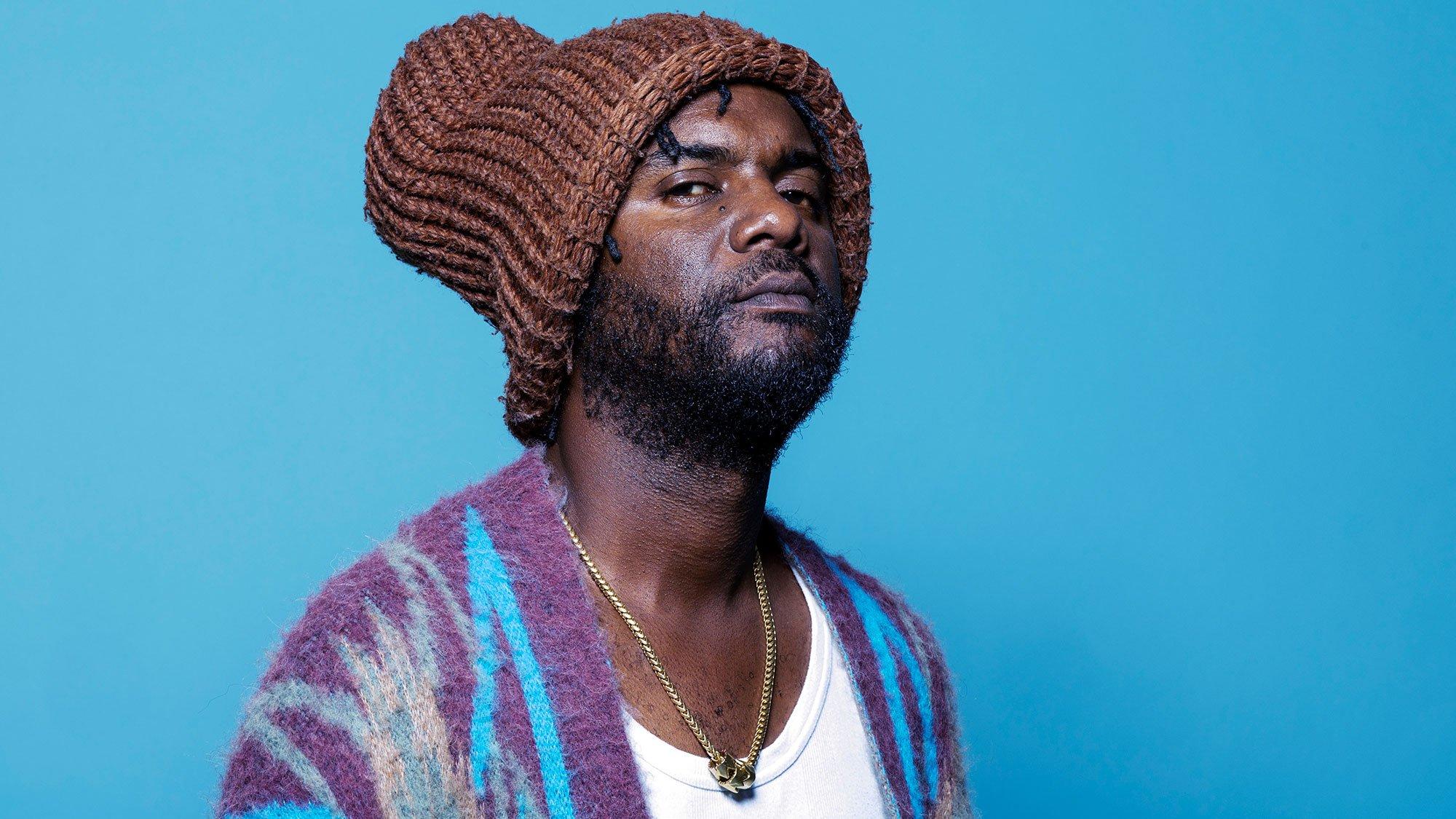

Gary Clark, Jr. On 'JPEG RAW': How A Lockdown Jam Session, Bagpipes & Musical Manipulation Led To His Most Eclectic Album Yet

Gary Clark, Jr.'s latest record, 'JPEG RAW,' is an evolution in the GRAMMY-winning singer and guitarist's already eclectic sound. Clark shares the process behind his new record, which features everything from African chants to a duet with Stevie Wonder.

Stevie Wonder once said "you can’t base your life on people’s expectations." It’s something guitarist and singer Gary Clark, Jr. has taken to heart as he’s built his own career.

"You’ve got to find your own thing," Clark tells GRAMMY.com.

Clark recently duetted with Wonder on "What About The Children," a song on his forthcoming album. Out March 22, JPEG RAW sees Clark continue to evolve with a mixtape-like kaleidoscope of sounds.

Over the years, Clark has ventured into rock, R&B, hip-hop blues, soul, and country. JPEG RAW is the next step in Clark's eclectic sound and sensibility, the result of a free-flowing jam session held during COVID-19 lockdown. Clark and his bandmates found freedom in not having a set path, adding elements of traditional African music and chants, electronic music, and jazz into the milieu.

"We just kind of took it upon ourselves to find our own way and inspire ourselves," says Clark, a four-time GRAMMY winner. "And that was just putting our heads together and making music that we collectively felt was good and we liked, music we wanted to listen to again."

The creation process was simultaneously freeing and scary.

"It was a little of the unknown and then a sense of hope, but also after there was acceptance and then it was freeing. I was like, all right, well, I guess we’re just doing this," Clark recalls. "It was an emotional, mental rollercoaster at that time, but it was great to have these guys to navigate through it and create something in the midst of it."

JPEG RAW is also deeply personal, with lyrics reflecting on the future for Clark himself, his family, and others around the globe. While Clark has long reflected on political and social uncertainties, his new release widens the lens. Songs like "Habits" examine a universal humanity in his desire to avoid bad habits, while "Maktub" details life's common struggles and hopes.

Clark and his band were aided in their pursuit by longtime collaborator and co-producer Jacob Sciba and a wide array of collaborators. Clark’s prolific streak of collaborations continued, with the album also featuring funk master George Clinton, electronic R&B/alt-pop artist Naala, session trumpeter Keyon Harrold, and Clark’s sisters Shanan, Shawn, and Savannah. He also sampled songs by Thelonious Monk and Sonny Boy Williamson.

Clark has also remained busy as an actor (he played American blues legend Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis) and as a music ambassador (he was the Music Director for the 23rd Annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor).

GRAMMY.com recently caught up with Clark, who will kick off his U.S. tour May 8, about his inspirations for JPEG RAW, collaborating with legendary musicians, and how creating music for a film helped give him a boost of confidence in the studio.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You incorporated traditional African music on JPEG RAW. How did it affect your songwriting process?

Well, I think traveling is how it affected my songwriting process. I was over in London, and we played a show with Songhoy Blues, and I was immediately influenced. I was like, "dang, these are my musical brothers from all the way across the world."

I always kind of listened to West African funk and all that kind of stuff. So, I was just listening to that in the studio, and just kind of started messing around with the thing. And that just kind of evolved from there. I was later told by Jacob Sciba that he was playing that music trying to brainwash me into leaning more in that direction. I thought we were just genuinely having a good time exploring music together, and he was trying to manipulate me. [Laughs.]

I quit caring about what people thought about me wanting to be a certain thing. I think that being compared to Jimi Hendrix is a blessing and a curse for me because I'm not that. I will never be that. I never wanted to imitate or copy that, no disrespect.

You’ve got to find your own thing. And my own thing is incorporating all the styles of music that I love, that I grew up on, and [was] influenced by as a pre-teen/teenager. To stay in one space and just be content doing that has never been my personality ever…I do what I like.

I read that you play trumpet at home and also have a set of bagpipes, just in case the mood strikes.

I used to go collect instruments and old cameras from thrift stores and vintage shops and flea markets. So, I saw some bagpipes and I just picked them up. I've got a couple of violins. I don't play well at all — if you could consider that even playing. I've got trumpet, saxophone, flutes, all kinds of stuff just in case I can use these instruments in a way that'll make me think differently about music. It'll inspire me to go in a different direction that I've maybe never explored before, or I can translate some of that into playing guitar.

One of my favorite guitarists, Albert Collins, was really inspired by horn players. So, if you can understand that and apply that to your number one instrument, maybe it could affect you.

Given recent discussions about advancements in AI and our general inundation with technology, the title of your album is very relevant. What about people seeing life through that filter concerns you? Why does the descriptor seem apt?

During the pandemic, since I wasn't out in the world, I was on my phone and the information I was getting was through whatever social media platforms and what was going on in certain news outlets, all the news outlets. I'm just paying attention and I'm just like, man, there's devastation.

I realized that I don't have to let it affect me. Just because things are accessible doesn't mean that you need to [access them]. It just made me think that I needed to do less of this and more of being appreciative of my world that's right in front of me, because right now it is really beautiful.

You’ve said the album plays out like a film, with a wide range of emotions throughout. What was it like seeing the album have that film-like quality?

I had conversations with the band, and I'd expressed to them that I want to be able to see it. I want to be able to see it on film, not just hear it. Keyboardist Jon Deas is great with [creating a] sonic palate and serving a mood along with [Eric] "King" Zapata who plays [rhythm] guitar. What he does with the guitar, it serves up a mood to you. You automatically see a color, you see a set design or something, and I just said, "Let's explore that. Let's make these things as dense as possible. Let's go like Hans Zimmer meets John Lee Hooker. Let's just make big songs that kind of tell some sort of a story."

Also, we were stuck to our own devices, so we had to use our imagination. There was time, there was no schedule. So, we were free, open space, blank canvas.

The album opens with "Maktub," which is the Arabic word for fate or destiny. How has looking at different traditions given you added clarity with looking at what's happening here in the U.S.?

I was sitting in the studio with Jacob Sciba and my friend Sama'an Ashrawi and we were talking about the history of the blues. And then we started talking about the real history of the blues, not just in its American form, in an evolution back to Africa. You listen to a song like "Maktub," and then you listen to a song like, "Baby What You Want Me to Do" by Jimmy Reed….

The last record was This Land, but what about the whole world? What about not just focusing on this, but what else is going on out there? And we drew from these influences. We talked about family, we talked about culture, we talked about tradition, we talked about everything. And it's like, let's make it inclusive, build the people up. Let's build ourselves up. It’s not just about your small world, it’s about everybody’s feelings. Sometimes they're dealt with injustice and devastation everywhere, but there's also this global sense of hope. So, I just wanted to have a song that had the sentiment of that.

I really enjoyed the song’s hopeful message of trying to move forward.

Obviously, things are a little bit funky around here, and I don't have any answers. But maybe if we got our heads together and brainstorm, we could all figure something out instead of … struggling or suffering in silence. It's like, let's find some light here.

But part of the talks that I had with Sama'an and his parents over a [video] call was music. He’s from Palestine, and growing up music was a way to connect. Music was a way to find happiness in a place where that wasn't an everyday convenience, and that was really powerful. That music is what brought folks together and brought joy and built a community and a common way of thinking globally. They were listening to music from all over the world, American music, rock music, and that was an influence.

The final song on the album, "Habits," sounds like it was the most challenging song to put together. What did you learn from putting that song together?

Well, that song originally was a bunch of different pieces, and I thought that they were different songs, and I was singing the different parts to them, and then I decided to put them all together. I think I was afraid to put them all together because we were like, "let's not do these long self-indulgent pieces of music. Let's keep it cool." But once I put these parts together and put these lyrics together, it just kind of made sense.

I got emotional when I was singing it, and I was like, This is part of using this as an outlet for the things that are going on in life. We went and recorded it in Nashville with Mike Elizondo and his amazing crew, and it's like, yep, we're doing it all nine minutes of it.

You collaborated with a bunch of musicians on this album, including Naala on "This Is Who We Are." What was that experience like?

Working with Naala was great. That song was following me around for a couple of years, and I knew what I wanted it to sound like, but I didn't know how I was going to sing it. I had already laid the musical bed, and I think it was one of the last songs that we recorded vocals on for the album.

Lyrically, it’s like a knight in shining armor or a samurai, and there's fire and there's war, and this guy's got to go find something. It was like this medieval fairytale type thing that I had in my head. Naala really helped lyrically guide me in a way that told that story, but was a little more personal and a little more vulnerable. I was about to give up on that song until she showed up in the studio.

"What About the Children" is based on a demo that you got from Stevie Wonder. You got to duet with him, what was that collaboration like?

Oh, it was great. It was a life-changing experience. The guy's the greatest in everything, he was sweet, the most talented, hardworking, gracious, humble, but strong human being I've been in a room with and been able to create with.

I was in shock when I left the studio at how powerful that was and how game changing and eye-opening it was. It was educational and inspiring. It was like before Stevie and after Stevie.

I imagine it was also extra special getting to have your sisters on the album.

Absolutely. We got to sing with Stevie Wonder; we used to grow up listening to George Clinton. They've stuck with us throughout my whole life. So, to be able to work with him and George Clinton — they came in wanting to do the work, hardworking, badass, nice, funny — it was a dream.

Stevie Wonder and George Clinton are just different. They're pioneers and risk takers. For a young Black kid from Texas to see that and then later to be able to be in a room with that and get direct education and conversation…. It's an experience that not everybody gets to experience, and I'm grateful that I did, and hopefully we can do it again.

In 2022, you acted in Elvis. What are the biggest things you've learned from expanding into new creative areas?

I really have to give it up to a guy named Jeremy Grody…I went to his studio with these terrible demos that I had done on Pro Tools…and this guy helped save them and recreate them. I realized the importance of quality recordings. Jeremy Grody was my introduction to the game and really set me up to have the confidence to be able to step in rooms like that again.

I played some songs in the film, and I really understood how long a film day was. It takes all day long, a lot of takes, a lot of lights, a lot of big crews, big production.

I got to meet Lou Reed [while screening the film] at the San Sebastian Film Festival, and I was super nervous in interviews. I was giving away the whole movie. And Lou Reed said, "Just relax and have fun with all this s—." I really appreciated that.

Do you have a dream role?

I don't have a dream role, but I do know that if I was to get into acting, I’d really dive into it. I would want to do things that are challenging. I like taking risks. I want to push it to the limit. I would really like to understand what it's like to immerse yourself in the character and in the script and do it for real.

You're about to go out on tour. How will the show and production on this tour compare with the past ones?

We're building it currently, but I'm excited about what we got in store as far as the band goes. There are a few additions. I've got my sisters coming out with me. It's just going to be a big show.There's a new energy here, and I'm excited to share that with folks.

Photo: Edward Wong/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

feature

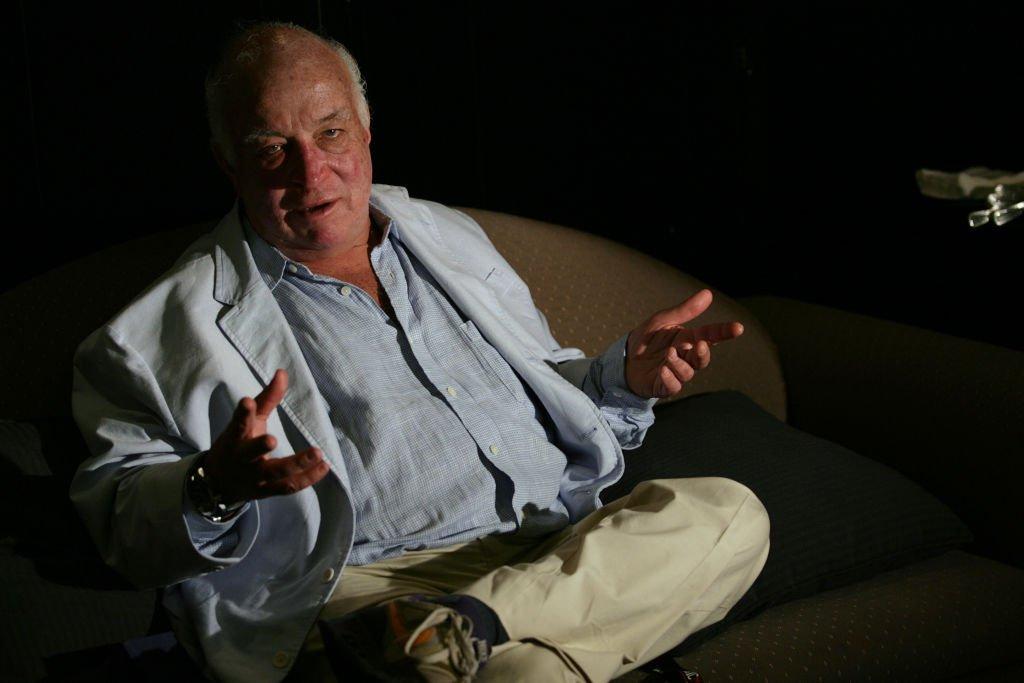

Remembering Seymour Stein: Without The Record Business Giant, Music Would Be Unrecognizable

The music man who signed everyone from the Ramones to Madonna will be profoundly missed throughout the global music community. He passed away on Apr. 8 at 80.

There’s a Belle and Sebastian song titled “Seymour Stein” that evokes a real-life, lavish feast between the soft-spoken Scottish indie band and the record company executive.

In the 1998 ballad, singer Stuart Murdoch details the tension between their working class identities and the dizzying prospects that Stein held in the palm of his hand. “Promises of fame, promises of fortune/ L.A. to New York/ San Francisco, back to Boston,” Murdoch dreamily sings. But he demurs, thinking of a girl back home in the country: “My thoughts are far away.”

There was a very good reason Murdoch and company associated Stein with an almost blindingly paradisiacal vision of music success. For an entire generation of alternative weirdos, Stein — the co-founder of Sire Records and vice president of Warner Bros. Records — was the guy who made it happen.

Sadly, Stein passed away on April 2 at his home in Los Angeles of cancer at the age of 80. This seismic loss to the global music community has rightfully earned tributes from far-flung corners of the music industry. Many, like his signee Madonna, openly pondered where their lives would be without his razor-sharp perception and adoration of all things music.

Think of the three-or-four-chord powderkeg of the Ramones’ 1977 self-titled debut, and the CBGB-adjacent army that answered to its detonation: Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Richard Hell and the Voldoids — on and on. Stein signed them all to Sire, either initiating their careers, as per the Ramones, or heralding their second acts, as he did the Replacements.

That paradigm arguably amounted to the biggest shift in guitar-based music since the Beatles — the ratcheting-down of opulent ‘70s rock into something leaner, meaner, and arguably more honest. But even that’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Stein's influence on music and culture at large.

Stein was the man who signed Madge, a profoundly pivotal figure in the following decade. And the rest of his resume was staggering: the Smiths, the Cure, Seal, k.d. lang, Brian Wilson, Lou Reed, Body Count… the list goes on.

He helped to establish the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, by way of the foundation of the same name, initiated by Ahmet Ertegun in 1983 — and was himself inducted in 2005. In 2018, the Recording Academy bestowed him with a coveted Trustees Award, which acknowledged his decades of service to the music community.

Indeed, the music man’s loss reverberates throughout the world’s leading society of music people.

“Seymour Stein was one of the greatest A&R executives of all time,” Ruby Marchand, the Chief Awards & Industry Officer at the Recording Academy, tells GRAMMY.com. “His passion, magnetic energy and natural curiosity underscored a lifelong dedication to unique artistry.

“He especially prized the art of songwriting and had an encyclopedic knowledge of songs, often bursting out in song to regale and delight friends and colleagues,” recalls Marchand, who worked with Stein for decades. “Seymour traveled the globe for decades and basked in the glow of discovering emerging artists singing to small audiences, from Edmonton to Seoul.

“He was a doting mentor, advisor, cheerleader and advocate for hundreds of us in the industry worldwide,” she concludes. “We cherish him and miss him terribly, and know how fortunate we were to have had him in our lives.”

The Recording Academy hails the late, great Stein for his monumental achievements in the music industry — ones that have fundamentally altered humanity’s universal language forever.

Mogul Moment: How Quincy Jones Became An Architect Of Black Music

list

20 Albums Turning 50 In 2023: 'Innervisions,' 'Dark Side Of The Moon' 'Catch A Fire' & More

1973 saw a slew of influential records released across genres — many of which broke barriers and set standards for music to come. GRAMMY.com reflects on 20 albums that, despite being released 50 years ago, continue to resonate with listeners today.

Fifty years ago, a record-breaking 600,000 people gathered to see the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band and the Band play Summer Jam at Watkins Glen. This is just one of many significant historical events that happened in 1973 — a year that changed the way music was seen, heard and experienced.

Ongoing advancements in music-making tech expanded the sound of popular and underground music. New multi-track technology was now standard in recording studios from Los Angeles to London. Artists from a variety of genres experimented with new synthesizers, gadgets like the Mu-Tron III pedal and the Heil Talk Box, and techniques like the use of found sounds.

1973 was also a year of new notables, where now-household names made their debuts. Among these auspicious entries: a blue-collar songwriter from the Jersey Shore, hard-working southern rockers from Jacksonville, Fla. and a sister group from California oozing soul.

Along a well-established format, '73 saw the release of several revolutionary concept records. The Eagles’ Desperado, Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, Lou Reed’s Berlin and the Who’s Quadrophenia are just a few examples that illustrate how artists used narrative techniques to explore broader themes and make bigger statements on social, political and economic issues — of which there were many.

On the domestic front, 1973 began with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Roe v. Wade. Internationally, the Paris Peace Accords were signed — starting the long process to end the Vietnam War. An Oil crisis caused fuel prices to skyrocket in North America. Richard Nixon started his short-lived second term as president, which was marked by the Watergate scandal.

Politics aside, the third year of the '70s had it all: from classic- and southern-rock to reggae; punk to jazz; soul and R&B to country. Read on for 20 masterful albums with something to say that celebrate their 50th anniversary in 2023.

Band On The Run - Paul McCartney & Wings

Laid down at EMI’s studio in Lagos, Nigeria and released in December 1973, the third studio record by Paul Mcartney & Wings is McCartney’s most successful post-Beatles album. Its hit singles "Jet" and the title cut "Band on the Run" helped make the record the biggest-selling in 1974 in both Australia and Canada.

Band on the Run won a pair of GRAMMYS the following year: Best Vocal Performance by a Duo, Group or Chorus and Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical. McCartney added a third golden gramophone for this record at the 54th awards celebration when it won Best Historical Album for the 2010 reissue. In 2013, Band on the Run was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

Head Hunters - Herbie Hancock

Released Oct. 13, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters was recorded in just one week; its

four songs clock in at just over 40 minutes. That the album was not nominated in the jazz category, but instead Best Pop Instrumental Performance, demonstrates how Hancock was shifting gears.

Head Hunters showed Hancock moving away from traditional instrumentation and playing around with new synthesizer technology — especially the clavinet — and putting together a new band: the Headhunters. Improvisation marks this as a jazz record, but the phrasing, rhythms and dynamics of Hancock’s new quintet makes it equal parts soul and R&B with sprinkles of rock 'n' roll.

The album represented a commercial and artistic breakthrough for Hancock, going gold within months of its release. "Watermelon Man" and "Chameleon," which was nominated for a Best Instrumental GRAMMY Award in 1974, were later both frequently sampled by hip-hop artists in the 1990s.

Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. - Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Springsteen, 22, was the new kid in town in 1973. This debut was met with tepid reviews. Still, Greetings introduced Springsteen’s talent to craft stories in song and includes many characters The Boss would return to repeatedly in his career. The album kicks off with the singalong "Blinded by the Light," which reached No. 1 on the Billboard 100 four years later via a cover done by Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. This was the first of two records Springsteen released in 1973; The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle arrived before the end of the year — officially introducing the E Street Band.

Innervisions - Stevie Wonder

This Stevie Wonder masterpiece shows an artist, in his early 20s, experimenting with new instrumentation such as TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra) — the world’s largest synth — and playing all instruments on the now-anthemic "Higher Ground."

The song reached No.1 on the U.S. Hot R&B Singles Chart, and Innervisions peaked at No. 4. The album won three GRAMMYS the following year, including Album Of The Year. Wonder was the first Black artist to win this coveted golden gramophone. In 1989, Red Hot Chili Peppers kept the original funk, but injected the song with a lot of rock on their cover — the lead single from Mother’s Milk.

The Dark Side Of The Moon - Pink Floyd

Critics perennially place this Pink Floyd album, the band's eighth studio record, as one of the greatest of all-time. The Dark Side of the Moon hit No.1 and stayed on the Billboard charts for 63 weeks.

A sonic masterpiece marked by loops, synths, found sounds, and David Gilmour’s guitar bends, Dark Side of the Moon is also a concept record that explores themes of excessive greed on tracks like "Money." Ironically, an album lambasting consumerism was the top-selling record of the year and has eclipsed 45 million sales worldwide since its release. The album’s cover has also become one of the most recognized in the history of popular music.

Pronounced 'lĕh-'nérd 'skin-'nérd - Lynyrd Skynyrd

This debut release features several of the northern Florida rockers' most beloved songs: "Gimme Three Steps," "Tuesday’s Gone" and "Simple Man." The record, which has since reached two-times platinum status with sales of more than two million, also includes the anthemic "Free Bird," which catapulted them to stardom. The song with its slow-build and definitive guitar solo and jam in the middle became Lynyrd Skynyrd's signature song that ended all their shows; it also became a piece of pop culture with people screaming for this song during concerts by other artists.

Houses Of The Holy - Led Zeppelin

The first Led Zeppelin record of all originals — and the first without a Roman numeral for a title — Houses of the Holy shows a new side of these British hardrockers. Straying from the blues and hard rock of previous records, Houses of the Holy features funk (“The Ocean” and “The Crunge”) and even hints of reggae (“D’Yer Mak’er”). This fifth studio offering from Page, Plant, Jones and Bonham also includes one of this writer’s personal Zeppelin favorites — "Over the Hills and Far Away.” The song was released as the album’s first U.S. single and reached No. 51 on the Billboard charts. Despite mixed reviews from critics, Houses of the Holy eventually achieved Diamond status for sales of more than 10 million. Interesting fact: the song “Houses of the Holy” actually appears on the band’s next record (Physical Graffiti).

Quadrophenia - The Who

The double-album rock opera followed the critical success of Tommy and Who’s Next. Pete Townshend composed all songs on this opus, which was later adapted into a movie. And, in 2015, classically-scored by Townshend’s partner Rachel Fuller for a new generation via a symphonic version (“Classic Quadrophenia”). The story chronicles the life of a young mod named Jimmy who lives in the seaside town of Brighton, England. Jimmy searches for meaning in a life devoid of significance — taking uppers, downers and guzzling gin only to discover nothing fixes his malaise. With sharp-witted songs, Townshend also tackles classicism. His band of musical brothers: Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon provide some of their finest recorded performances. The album reached second spot on the U.S. Billboard chart.

Berlin - Lou Reed

Produced by Bob Ezrin, Berlin is a metaphor. The divided walled city represents the divisive relationships and the two sides of Reed — on stage and off. The 10 track concept record chronicles a couple’s struggles with drug addiction, meditating on themes of domestic abuse and neglect. As a parent, try to listen to "The Kids" without shedding a tear. While the couple on the record are named Caroline and Jim, those who knew Reed’s volatile nature and drug dependency saw the parallels between this fictionalized narrative and the songwriter’s life.

Catch A Fire - Bob Marley & the Wailers

The original cover was enclosed in a sleeve resembling a Zippo lighter. Only 20,000 of this version were pressed. Even though it was creative and cool, cost-effective it was not — each individual cover had to be hand-riveted. The replacement, which most people know today, introduces reggae poet and prophet Robert Nesta Marley to the world. With a pensive stare and a large spliff in hand, Marley tells you to mellow out and listen to the tough sounds of his island home.

While Bob and his Wailers had been making music for nearly a decade and released several records in Jamaica, Catch a Fire was their coming out party outside the Caribbean. Released in April on Island Records, the feel-good reggae rhythms and Marley’s messages of emancipation resonated with a global audience. A mix of songs of protest ("Slave Driver," "400 years") and love ("Kinky Reggae"), Catch A Fire is also notable for "Stir it Up," a song American singer-songwriter Johnny Nash had made a Top 15 hit the previous year.

The New York Dolls - The New York Dolls

The New York Dolls burst on the club scene in the Big Apple, building a cult following with their frenetic and unpredictable live shows. The Dolls' hard rock sound and f-you attitude waved the punk banner before the genre was coined, and influenced the sound of punk rock for generations. (Bands like the Sex Pistols, the Ramones and KISS, cite the New York Dolls as mentors.) Singer-songwriter Todd Rundgren — who found time to release A Wizard, A True Star this same year — produced this tour de force. From the opening "Personality Crisis," this five-piece beckons you to join this out-of-control train.

Aladdin Sane - David Bowie

This David Bowie record followed the commercial success of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders from Mars. Many critics unfairly compare the two. A career chameleon, with Aladdin Sane, Bowie shed the Ziggy persona and adopted another alter-ego. The title is a pun that means: "A Lad Insane." For the songwriter, this record represented an attempt to break free from the crazed fandom Ziggy Stardust had created.

A majority of the songs were written the previous year while Bowie toured the United States in support of Ziggy. Journal in hand, the artist traveled from city to city in America and the songs materialized. Most paid homage to what this “insane lad” observed and heard: from debauchery and societal decay ("Cracked Actor") to politics ("Panic in Detroit") to punk music ("Watch That Man"). Top singles on Aladdin Sane were: "The Jean Genie" and "Drive-In Saturday." Both topped the U.K. charts.

Faust IV -Faust

This fourth studio album — and the final release in this incarnation by this experimental avant-garde German ambient band — remains a cult classic. Recorded at the Manor House in Oxfordshire, England (Richard Branson’s new Virgin Records studio and the locale where Mike Oldfield crafted his famous debut Tubular Bells, also released in 1973), Faust IV opens with the epic 11-minute instrumental "Krautrock" — a song that features drones, clusters of tones and sustained notes to create a trance-like vibe. Drums do not appear in the song until after the seven minute mark.

The song is a tongue-in-cheek nod to the genre British journalists coined to describe bands like Faust, which musicians largely did not embrace. The rest of Faust IV is a sonic exploration worthy of repeated listens and a great place to start if you’ve ever wondered what the heck Krautrock is.

Brothers & Sisters - the Allman Brothers Band

Great art is often born from grief, and Brothers & Sisters is exemplary in this way. Founding member Duanne Allman died in 1971 and bassist Berry Oakley followed his bandmate to the grave a year later; he was killed in a motorcycle accident in November 1972. Following this pair of tragedies, the band carried on the only way they knew how: by making music.

With new members hired, Brothers & Sisters was recorded with guitarist Dicky Betts as the new de facto band leader. The Allman Brothers Band’s most commercially successful record leans into country territory from the southern rock of previous releases and features two of the band’s most popular songs: "Ramblin’ Man" and "Jessica." The album went gold within 48 hours of shipping and since has sold more than seven million copies worldwide.

Call Me - Al Green

Call Me is considered one of the greatest soul records of the 20th century and Green’s pièce de résistance. The fact this Al Green album features three Top 10 Billboard singles — "You Ought to Be With Me," "Here I Am" and the title track — helps explain why it remains a masterpiece. Beyond the trio of hits, the soul king shows his versatility by reworking a pair of country songs: Hank Williams’ "I’m so Lonesome I Could Cry," and Willie Nelson’s "Funny How Time Slips Away."

Killing Me Softly - Roberta Flack

This Roberta Flack album was nominated for three GRAMMY Awards and won two: Record Of The Year and Best Female Vocal Pop Performance at the 1974 GRAMMYs (it lost in the Album of the Year category to Innervisions). With equal parts soul and passion, Flack interprets beloved ballads that showcase her talent of taking others’ songs and reinventing them. Producer Joel Dorn assembled the right mix of players to back up Flack — adding to the album’s polished sound. Killing Me Softly has sold more than two million copies and, in 2020, Roberta Flack received the GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award.

The album's title cut became a No.1 hit in three countries and, in 1996, the Fugees prominently featured Lauryn Hill on a version that surpassed the original: landing the No.1 spot in 21 countries. The album also includes a pair of well-loved covers: Leonard Cohen’s "Suzanne" and Janis Ian’s wistful "Jesse," which reached No. 30.

Bette Midler - Bette Middler

Co-produced by Arif Mardin and Barry Manilow, the self-titled second studio album by Bette Midler was an easy- listening experience featuring interpretations of both standards and popular songs. Whispers of gospel are mixed with R&B and some boogie-woogie piano, though Midler’s voice is always the star. The record opens with a nod to the Great American Songbook with a reworking of Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael’s "Skylark." The 10-song collection also features a take on Glenn Miller’s "In the Mood," and a divine cover of Bob Dylan’s "I Shall be Released." The record peaked at No. 6 on the U.S. charts.

Imagination - Gladys Knight & the Pips

Released in October, Imagination was Gladys Knight & the Pips' first album with Buddha Records after leaving Motown, and features the group’s only No. 1 Billboard hit: "Midnight Train to Georgia." The oft-covered tune, which won a GRAMMY the following year, and became the band’s signature, helped the record eclipse a million in sales, but it was not the only single to resonate. Other timeless, chart-topping songs from Imagination include "Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me," and "I’ve Got to Use My Imagination."

The Pointer Sisters - The Pointer Sisters

The three-time GRAMMY-winning Pointer Sisters arrived on the scene in 1973 with this critically-acclaimed self-titled debut. Then a quartet, the group of sisters from Oakland, California made listeners want to shake a tail feather with 10 songs that ranged from boogie-woogie to bebop. Their sisterly harmonies are backed up by the San Francisco blues-funk band the Hoodoo Rhythm Devils. The record opens with "Yes We Can," a hypnotic groove of a song written by Allen Toussaint which was a Top 15 hit alongside another cover, Willie Dixon’s "Wang Dang Doodle."

Behind Closed Doors - Charlie Rich

This pop-leaning country record of orchestral ballads, produced by Billy Sherrill, made Rich rich. The album has surpassed four million in sales and remains one of the genre’s best-loved classics. The album won Charlie Rich a GRAMMY the following year for Best Country Vocal Performance Male and added four Country Music Awards. Behind Closed Doors had several hits, but the title track made the most impact. The song written by Kenny O’Dell, and whose title was inspired by the Watergate scandal, was the first No.1 hit for Rich. It topped the country charts where it spent 20 weeks in 1973. It was also a Billboard crossover hit — reaching No. 15 on the Top 100 and No. 8 on the Adult Contemporary charts.

Photo: Bret Curry

interview

Will Sheff Swears Off Primary Colors, Reductive Narratives & Pernicious Self-Mythology On New Album 'Nothing Special'

The Okkervil River bandleader's story has been occasionally oversimplified and distorted in the name of commerce — and he's unwilling to let that happen again. Will Sheff discusses the life changes that informed his new album, 'Nothing Special.'

Just before logging on to Zoom to interview Will Sheff, who's out under his own name 20 years after his proper debut, this journalist spent some time tearing down vines climbing up a tree — sapping its nutrients, stymying its growth, and, if left unchecked, killing it.

Given Sheff's ups and downs in the business, the scene led to the question: Is the tree the thousands-year-old wellspring of human musical expression, which is fully able to survive and thrive regardless of capitalistic hijacking? And are the vines the music industry?

"The music business doesn't have to be this way," Sheff, a GRAMMY nominee, tells GRAMMY.com. Coming from him, this is a weighty statement.

The Okkervil River bandleader had just been describing how press narratives distort and reduce reality into cartoonish, unrecognizable forms. Six years ago, a candid, self-written bio for his album Away that touched on his grandfather's death — but was about a multitude of subjects — led to the narrative that it was all about that. Damaging in a more immediate, practical sense is the financial hit he projects he'll take from his upcoming US and Europe tours — thousands in the red.

That financial horror is partly because Sheff finally decided to put Okkervil River to bed. Despite him being the final original member still in the band, that name carried a cachet which led to steeper guarantees.

In return, Sheff has gained an artistic freedom like he's arguably never experienced before — free reign to make whatever music he wants, unfettered from the expectations of those who really, really, really want him to make another Don't Fall in Love With Everyone You See, or Black Sheep Boy. And Sheff's new album, Nothing Special, released Oct. 7, shimmers with the hues of everything he is now, and all he can be from now on.

Musically, Nothing Special isn't so different from records like Away: if you trisect his career, Sheff has spent roughly the last third writing from a zone of serenity, devotion and encouragement — pretty much the polar opposite of old Okkervil River songs about murder and revenge and psychospiritual downfalls.

But his current collaborators — including Will Graefe, Christian Lee Hutson, and Death Cab for Cutie's Zac Rae —, give his approach a new depth, a fresh lilt. To say nothing of vocal contributions from Cassandra Jenkins and Eric D. Johnson of Fruit Bats and Bonny Light Horseman — who are both at the vanguard of forward-thinking singer-songwriter music.

Lyrically, we're dealing with a similar matrix as Away in terms of life stuff. But where said familial loss, including the partial dissolution of the previous Okkervil River band, informed Away, Nothing Special expands its scope. The album partly deals with moving to California, winding down his old band, swearing off alcohol, and caring for his ailing rescue dog, Larry.

And there's a profound loss at the center of it — that of Travis Nelsen, Okkervil River's awe-inspiring drummer and a larger-than-life personality, who had a fraternal bond with Sheff played in the band during their commercial zenith in the mid-2000s. Their friendship ended on a messy and sad note: as Nothing Special's title track goes, Nelsen "failed and fought/ In a pattern he was caught/And his family, they could not break through." Soon after the pandemic hit, Nelsen passed away.

Back to the tree, choked by the vines: Sheff would be "really unhappy" if Nelsen's life and legacy were sleuced into the oversimplification machine. He could have not mentioned him at all in this press cycle, for good reason — look what happened regarding the story of Away — but he chose to speak about him.

"Travis was a true connoisseur of rock lore, and I know that he wants to be remembered," Sheff says. "I didn't want to feel like I was profiting off of his sad story, and I want people to remember him. I want to do what I can to keep his name out there. Those were the factors that led me to be like, 'Alright: I'm going to be honest about this album.'"

And no matter whether Nothing Special is your thing or not — Sheff's intentionally not reading his own press — there's no question about it: honesty permeates every word, every groove, every expression.

GRAMMY.com sat down with Sheff to discuss the new album, his place in the industry apparatus, and the breathtaking vista of potential before him, now that he's been unshackled from the band that defined him — and somewhat confined him.

*Will Sheff. Photo: Bret Curry*

This interview has been edited for clarity.

It's common for artists to get burned out on their offerings long before they're actually released. Are you tired of talking about Nothing Special yet?

No, no, no. I barely talk to anybody about it, and I'm enjoying talking about it. I'll never stop feeling enthusiastic about the record. The only thing that's the mind — is anything to do with the business, which encompasses publicity and branding, which is what I'm engaging in right now as I'm talking to you.

I was saying this yesterday — I feel like I will very soon start repeating the same things. And I'll probably, always very tediously, say, "I've said this before, but…" because otherwise, I feel like a phony.

But the thing that's really a head trip is that you make an album, a song, or a collection of songs. And not everybody's like this — I think a lot of people are — but you're not necessarily thinking about the audience. What people are going to say it is, or what genre it is, or whatever.

You have to turn off that voice, or else you can't create.

Yeah, and you're kind of chewing on something in a song. It could be some really big thing that obsesses you that you need to solve, or it could be just some way to express beauty that you want to feel.

And then somebody comes around, if you're lucky enough that people care about what you did, and interviews you about it, and they ask you what went into the songs. And you tell them, because they asked you.

It inevitably ends up seeming very oversimplified, because that's what stories do. A good storyteller throws out some of the details and pumps up some of the other details to get people hooked.

It becomes crystallized, canonized. Reduced to primary colors.

Maybe other animals tell stories, but it feels like the most human thing in the universe — to tell stories and construct narratives. Story is one of the most beautiful things that we do, and one of the most damaging things that we do.

Thousands of people can die in a single day because of a story. Genocide, prejudice — these things come with all of these stories, you know what I mean? Or, like, "I'm in the right; I'm doing the right thing. The end justifies the means because of this story."

The point is, like you say, it's this complicated thing, and it gets simplified. And then somebody reads that interview — the simplified interview — and they're already imposing this simplified story on you.

Essentially, you end up with this thing that was really subtle, complex, reaching out in the darkness, a dialogue between you and whatever it is that makes you write, and it just kind of gets turned into a cartoon really, really quickly. And then you have to play along, or push against it, [when] pushing against it just seems sort of churlish or something like that.

The supreme irony of all of this is that this is something I've been trying to unpack for myself for decades, and oftentimes contributes to a lot of unhappiness for me, personally.

**How would you apply this thinking to Nothing Special?**

One of the things I was grappling with on this album was trying to not tell myself fake stories, and trying to not think too much about extrinsic rewards for what I'm doing.

Also, not trying to particularly peddle a really clichéd story that it feels like everybody has to peddle now, just to get somebody to turn their heads. Which is to say, "I'm the greatest!" — the most obvious thing. Rappers do it all the time; indie people do it sort of fake-ironically. It's just the currency we're asked to exchange ourselves in.

So, I do all this stuff, and then try to make this record, which really is a personal reflection of all this. But then, I have to promote it. I, like, literally pay a guy to promote it! I pay a company to get people to try to talk about me on this album, that's sort of like, "Hey, don't worry. Don't think about me too much." There's this really bizarre irony-slash-hypocrisy that may be in there that is really interesting, that I'm trying to negotiate.

In the four or five interviews I've done [at the time of this conversation], I don't feel like I've done anything really gross yet, in terms of selling myself in that cartoonish way. But it also feels like it's such a slippery slope — you know what I mean?

Just have fun with that tension! Conceptual dissonance is where so much beauty comes from. There's also that real danger of Travis and his legacy becoming distorted.

When I was working on Away, my grandfather had died, and he was a really big influence on my personality and all that stuff. It was very much on my mind. And I decided that for that press cycle, to not pay somebody to write a bio and just write the most transparent thing I could myself. And it didn't work the way I hoped it would.

What ended up happening was, there emerged this narrative of some guy who was devastated by his grandfather's death and wrote an album about it — which is, like, criminally distorted.

I had a lot going on, and I had him on my mind because his death was very sad. It was also very expected, and it was kind of a culmination of his story and life. I just feel like it turned into a distortion that made me unhappy.

When I wrote a lot of these songs [on Nothing Special] — and some of the songs that aren't on the record, because I wrote a lot of them — Travis would flit in and out of many of them. All the different ways that I was trying to celebrate him and grapple with what had happened. I could not say that. I could tell them to not put that in the biography. But I'm trying to be honest; that was a big part of it.

There are a lot of things that were a big part of it — moving, coming out to California, looking back on Okkervil River, then sort of dissolving Okkervil River. Caring for another being, starting over again, aging, looking at the rock 'n' roll business and the myth of rock 'n' roll.

And these things were not separated from each other; they were all in dialogue. I also wanted to pay tribute to Travis, because we loved each other like brothers.

*Will Sheff. Photo: Bret Curry*

Can you talk a little more about your relationship with Travis?

That's the most important friendship I've had in my life; maybe my friendship with Jonathan [Meiburg, author and leader of Shearwater], who is equally important. But Travis was a true connoisseur of rock lore, and I know that he wants to be remembered.

We had had a falling out over a really complicated bunch of factors. But I know from knowing him as well as I did, and from talking to a lot of his friends, that we still always loved each other and always wanted to reconcile.

I didn't want to feel like I was profiting off of his sad story, and I want people to remember him. I want to do what I can to keep his name out there. Those were the factors that led me to be like, "Alright: I'm going to be honest about this album."

But at the same time, I will be really unhappy if, when I look back on this whole promotion cycle, it got boiled down to "This was the concept album about how he was sad about Travis dying." Because it's not true. This album is about so many things, and it's all interwoven and intermingled.

Right before this interview, I tore down a bunch of vines off a tree in my yard because they were sucking out the nutrients. Does the tree symbolize art as a whole, and the vines are the music business?

Music has always been around, and the idea that it should have anything to do with business is crazy, when you think about it a little bit. It's just this bizarre shotgun wedding, trying to reconcile capitalism with an activity that people do that other people really appreciate.

Furthermore, I think the idea of musical celebrities, and musical stars, is also slightly gross. I like the idea that up until very recently, music was just something that a lot of people did. And they did it for fun! They did it for community, and for entertainment.

It was like, "My daughter's getting married! Have Joe come over; he plays the fiddle!" It wasn't like everybody was sitting around, interviewing Joe and asking him for the influences on the jig he just played, and Joe was wearing Wayfarers, giving cryptic answers to their questions before hopping on his private jet. It's kind of disgusting.

And those stories we talked about fold into that.

We love stories; I love those stories. I love stories about Bob Dylan and David Bowie and Iggy Pop and Alex Chilton. But as fun to think about as it is, it's a sick and f—ed up system — especially when it comes to getting to live a life that's extravagant, while other people are living these miserable, hand-to-mouth existences.

Because we love stories, it's really entertaining to have a Bowie. Maybe you can see yourself in the exaggerated, larger-than-life aspects of things that happened with Bowie. [But] I like that David Bowie never changed his name, and he was David Robert Jones.

I guess the best way to try to be a rock star is to just understand that you're really like a vessel for other people's projections and entertainment, and just go, "Hey, man, I'm just here to entertain. Please don't worship me. If I make you laugh, make you smile, give you a good Saturday night's entertainment, then it's worth me wearing this stupid outfit and acting like such an ass."

But if it's all about me getting some disproportionate reward, then it kind of becomes gross.

For a while, you've been making music that deals with something close to serenity, which is not a sexy nor clickable concept. Most fans probably got into Okkervil River almost 20 years ago, when you were screaming about murder. Can you talk about that tension between who you are and what people want you to be — or pay you to be?

Like any artist, you follow your nose — and when I was younger, I wrote in a younger way. I wrote in a way that was really informed by where I was at in my life, and where I had been — specifically, what I had experienced.

And I don't mean to make it sound like it's worse than anybody else, but I'd experienced a lot of pain and hurt. And — this is not uncommon with men — it sort of transformed into anger, and I had a lot to prove.

I think this is true of me now, and has always been true: I have a tendency to go there. When I'm writing, I have a tendency to want to go to the place that makes people — or me — uncomfortable.

Those songs, where I dealt with things like murder and suicide and very violent feelings — I don't regret any of those songs. I don't think that they came from a hurtful place, and I think, probably, at the end of the day, they were a net positive for people who really liked them. I hope and think they were more cathartic than stirring up shittiness, or anything like that.

But the engine for a lot of that was anger and hurt and pain, and as a human, I very much felt like I needed to figure out how to not hurt people, and how to help people, and be present for the people I loved and notice them and see them and pay attention to their feelings and not be unhappy.

Like, nobody wants me — and I certainly don't want any of my friends who are in their 40s — to be drug-addled, chasing tail, only wanting to play three chords on an electric guitar. You get older, and you start to see all the different tones and all the diversity of musical expression, and it's my job to always try to make it new and reflect what I want out of music. That was a real big shift.

Which isn't always appreciated by the drunken frat boys screaming for "Westfall."

Yeah, there are some people who really imprinted on the anger and the rage. And it wasn't just young men; I think it was women, too, who kind of identified with it.

Maybe they put me in that drawer. I don't think it was malicious, but it's like, they just want that again. But I don't want to be miserable. These days, I feel like I go there with religion and spirituality and big existential questions.

I think that maybe that actually makes people uncomfortable. And I think the discomfort that people feel about murder and violence is actually very familiar. We all like gross, grimy, dark anger, and I think some of the more spiritual stuff actually makes people very uncomfortable.

**I really enjoyed watching critics squirm at lines like "Brother, I believe in love" from the last record [2018's In the Rainbow Rain].**

Yeah, yeah. What's fun about that is just going full[-on] risking being called a stupid hippie. I like the idea of exposing yourself to criticism and failure.

I was talking to somebody about some record in the past, and they were encouraging me to write quote-unquote bulletproof pop songs. I was thinking about that metaphor, and nothing could be further from describing the kind of music I like.

I don't want my muse to be an impregnable fortress, a bulletproof vest, a tank rolling through town. I want it to be porous and vaporous. Easy to ignore, easy to make fun of. Going out on a limb, inviting the listener in.

It shouldn't be like an irrefutable argument; it should be just a strange artifact that you are called to interact with, or something.

**Even on that extreme end, your work never lands in a sense of gross grandiosity, or a Messianic complex. I love the ending of "Evidence" from Nothing Special, because a lesser songwriter or arranger would have built that chorus to absurd heights. Instead, you chose to let it waft in and out, and gently settle.**

It's funny how you talk about it being a decision, because I never thought about that. It speaks to the difference between the two ways of looking at a song — the making of it, and then the talking about it after, which are equally important, I think.

I always want to say "This is the song I'm most proud of," because I love all these songs in different ways. But "Evidence" really articulates a lot of fundamental feelings I have about life, at this point in my life. And I think the music does just as much to articulate them as the words. I really did want that song to be comforting. Soothing, and not necessarily papering over pain, but something that would make people feel fundamentally good.

When you're talking about turning it into a big chorus, that was something I thought a lot about in its absence on this record — never pushing anything.

"Like the Last Time" pushes, I guess, because that's just what naturally happened in the studio. That song wasn't supposed to rock out that hard. It just sort of happened. I'd say my biggest goal on this record was to never oversell anything.

I love how Nothing Special is predicated on these diatonic, very simple melodies. I know you've talked about Bill Fay in those terms.

When you say that, it's funny, because I don't think about things in terms of theory too much. But I definitely had this thing where I was like, "I want these songs to be melodically very singable, and lyrically very gettable," even if there's a lot in them.

You've made the difficult decision to go under your own name, despite the financial hit. But now, you've torn off the Band-Aid. You could theoretically just keep making solo records of any kind, and the fans will continue to follow you wherever you go. How do you see the next decade of your career?

I don't know what the future holds. And sometimes, when I look back on my favorite artists, it does feel like decades really have the power to destroy people's careers. A really obvious example is when alternative rock and grunge came along, and suddenly, all these '80s bands seemed like they were 100 years old. Some of them never recovered.

The closest thing we ever had to being connected to the zeitgeist was that brief 2006-to-2010 stretch. I don't think we were ever the front-runners. We would just be mentioned in the same conversation as a bunch of other bands.

I feel like I've managed to keep going and fly under the radar. When I think about my favorite artists with the longest careers — Dylan is an exception that proves the rule; he's not a good artist to compare your career to — I think about somebody like Michael Hurley.

I love that he's just been doing the same thing his whole life, and there's really never been a drop-off in quality. His records all sound the same; they're all really good! You're never like, "He's over the hill; he's passed around the bend now."

The most exciting thing about getting to be Will Sheff instead of Okkervil River is that I feel like there aren't any rules about what I can and can't do. When I made this record, I wasn't really thinking about whether it was Okkervil River or Will Sheff or anything other than just making music.

But as a result, I think [with] the next record, I'll feel a lot more emboldened to do whatever I want stylistically, and not feel like it has to square with someone's conception of what the brand Okkervil River sounds like.

You could go full Lovestreams, or you could play a single lute.

[Laughs.] Yeah, exactly! I could go like Sting and just start playing John Dowland on lute, and more power to me!

Alice Coltrane's Kirtan: Turiya Sings: Inside The Unearthly Beauty Of Her Long-Lost Devotional Album