Photos: Jeff Hahne/Getty Images; Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Erika Goldring/WireImage

news

2023 GRAMMYs To Pay Tribute To Lost Icons With Star-Studded In Memoriam Segment Honoring Loretta Lynn, Christine McVie, And Takeoff

The GRAMMY Awards segment will feature Kacey Musgraves in a tribute to Loretta Lynn; Sheryl Crow, Mick Fleetwood and Bonnie Raitt honoring Christine McVie; and Maverick City Music joining Quavo as they remember Takeoff, airing live on Sunday, Feb. 5.

The lineup for the 2023 GRAMMYs on Sunday, Feb 5, will include an In Memoriam segment paying tribute to some of those from the creative community that were lost this year with performances by GRAMMY-winning and -nominated artists.

The segment will feature Kacey Musgraves performing "Coal Miner's Daughter" in a tribute to three-time GRAMMY winner and 18-time nominee Loretta Lynn; Sheryl Crow, Mick Fleetwood and Bonnie Raitt honoring three-time GRAMMY winner Christine McVie with "Songbird"; and Maverick City Music joining Quavo for "Without You" as they remember the life and legacy of Takeoff.

The 2023 GRAMMYs, hosted by Trevor Noah, will broadcast live on Sunday, Feb. 5, at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT on the CBS Television Network live from the Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles. Viewers will also be able to stream the 2023 GRAMMYs live and on demand on Paramount+.

Before, during and after the 2023 GRAMMYs, head to live.GRAMMY.com for exclusive, never-before-seen content, including red carpet interviews, behind-the-scenes content, the full livestream of the 2023 GRAMMY Awards Premiere Ceremony, and much more.

Photo: Aitor Laspiur

interview

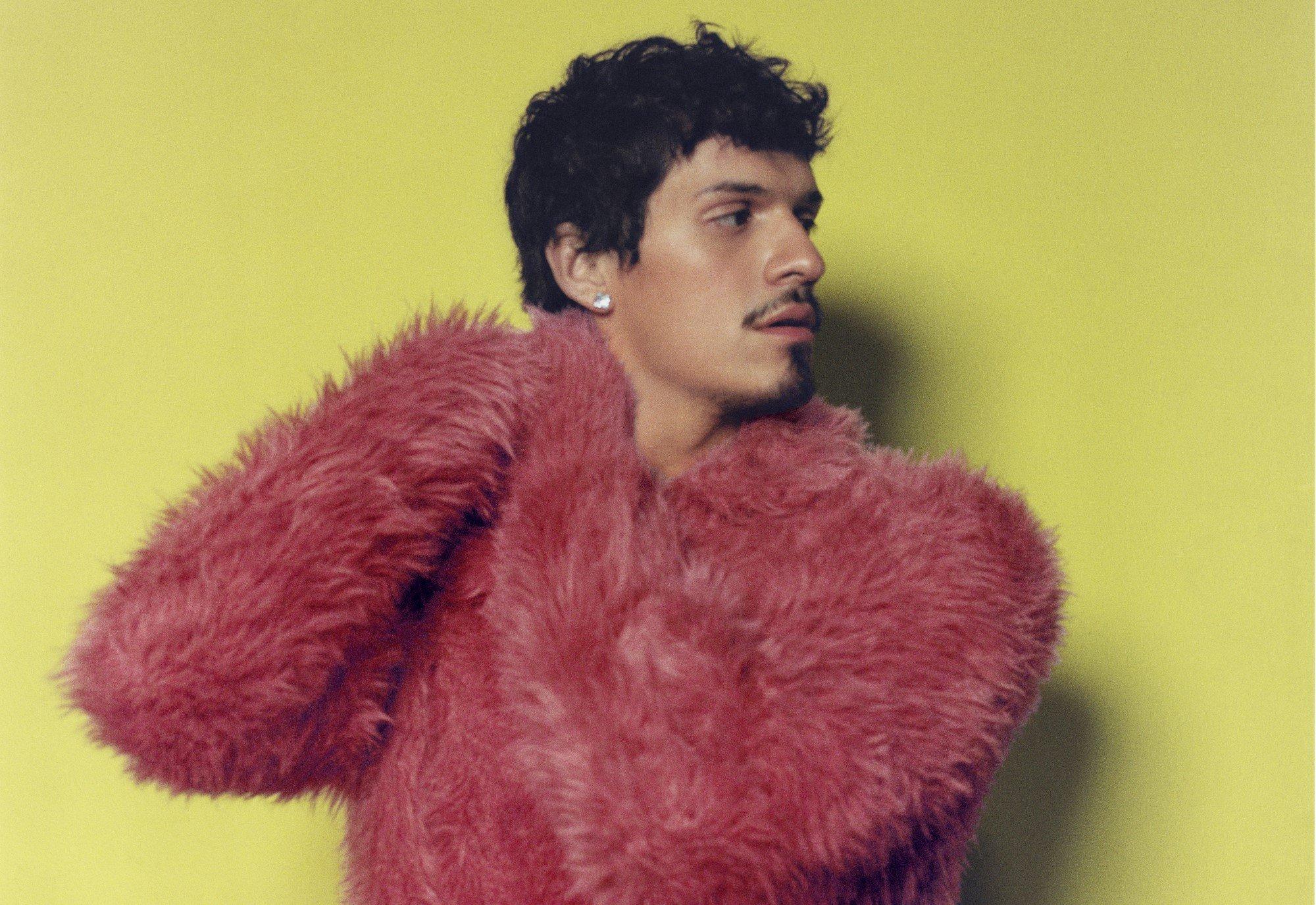

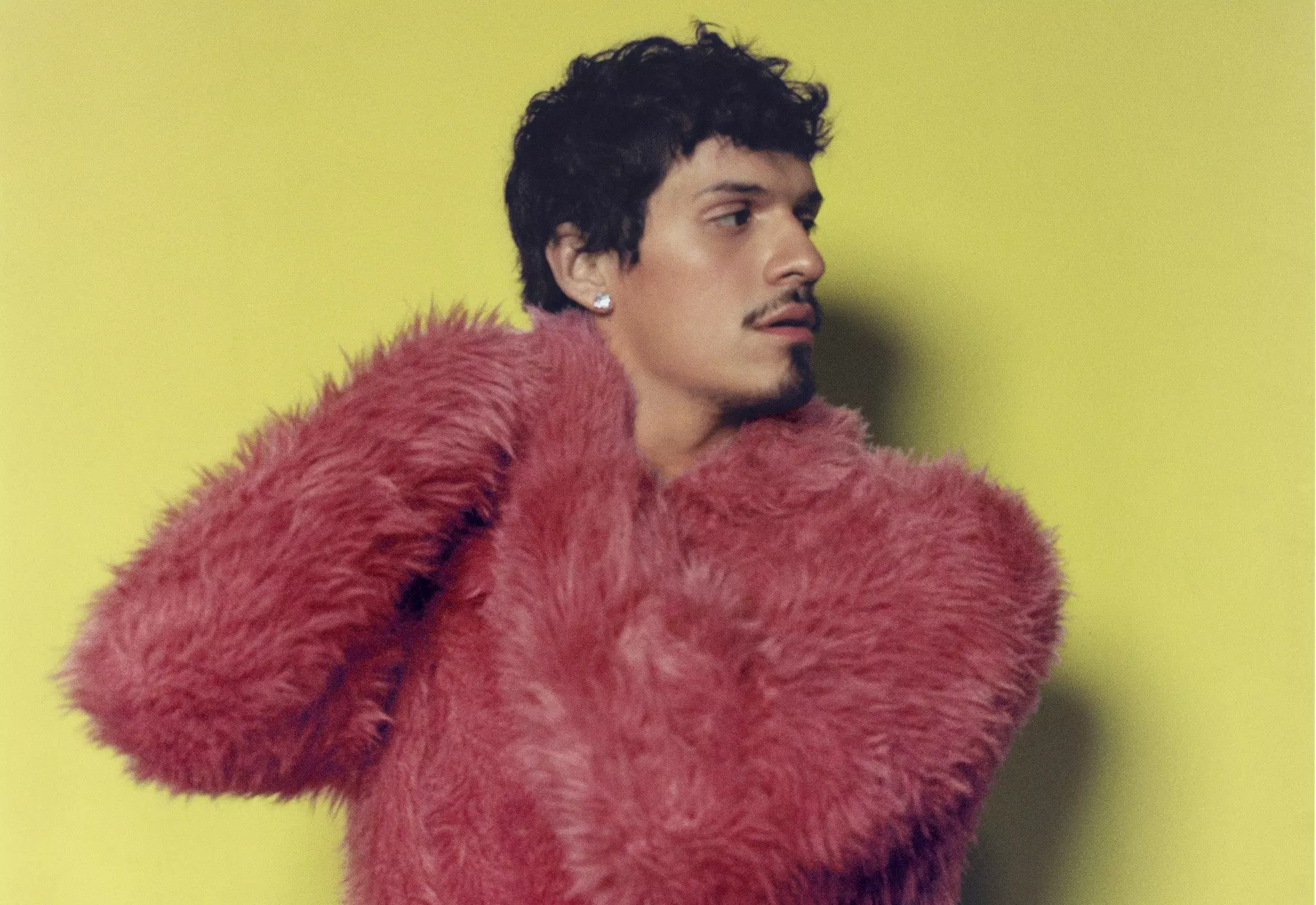

Omar Apollo Embraces Heartbreak And Enters His "Zaddy" Era On 'God Said No'

Alongside producer Teo Halm, Omar Apollo discusses creating 'God Said No' in London, the role of poetry in the writing process, and eventually finding comfort in the record's "proof of pain."

"Honestly, I feel like a zaddy," Omar Apollo says with a roguish grin, "because I'm 6'5" so, like, you can run up in my arms and stay there, you know what I mean?"

As a bonafide R&B sensation and one of the internet’s favorite boyfriends, Apollo is likely used to the labels, attention and online swooning that come with modern fame. But in this instance, there’s a valid reason for asking about his particular brand of "zaddyhood": he’s been turned into a Bratz doll.

In the middle of June, the popular toy company blasted a video to its nearly 5 million social media followers showing off the singer as a real-life Bratz Boy — the plastic version draped in a long fur coat (shirtless, naturally), with a blinged-out cross necklace and matching silver earrings as he belts out his 2023 single "3 Boys" from a smoke-covered stage.

The video, which was captioned "Zaddy coded," promptly went viral, helped along by an amused Apollo reposting the clip to his own Instagram Story. "It was so funny," he adds. "And it's so accurate; that's literally how my shows go. It made me look so glamorous, I loved it."

The unexpected viral moment came with rather auspicious timing, considering Apollo is prepping for the release of his hotly anticipated sophomore album. God Said No arrives June 28 via Warner Records.

In fact, the star is so busy with the roll-out that, on the afternoon of our interview, he’s FaceTiming from the back of a car. The day prior, he’d filmed the music video for "Done With You," the album’s next single. Now he’s headed to the airport to jet off to Paris, where he’ll be photographed front row at the LOEWE SS25 men’s runway show in between Sabrina Carpenter and Mustafa — the latter of whom is one of the few collaborators featured on God Said No.

Apollo’s trusted co-writer and producer, Teo Halm, is also joining the conversation from his home studio in L.A. In between amassing credits for Beyoncé (The Lion King: The Gift), Rosalía and J Balvin (the Latin GRAMMY-winning "Con Altura"), SZA ("Notice Me" and "Open Arms" featuring Travis Scott) and others, the 25-year-old virtuoso behind the boards had teamed up with Apollo on multiple occasions. Notably, the two collabed on "Evergreen (You Didn’t Deserve Me At All)," which helped Apollo score his nomination for Best New Artist at the 2023 GRAMMYs.

In the wake of that triumph, Apollo doubled down on their creative chemistry by asking Halm to executive produce God Said No. (The producer is also quick to second his pal’s magnetic mystique: "Don't get it twisted, he's zaddy, for sure.")

Apollo bares his soul like never before across the album’s 14 tracks, as he processes the bitter end of a two-year relationship with an unnamed paramour. The resulting portrait of heartbreak is a new level of emotional exposure for a singer already known for his unguarded vulnerability and naked candor. (He commissioned artist Doron Langberg to paint a revealing portrait of him for the cover of his 2023 EP Live For Me, and unapologetically included a painting of his erect penis as the back cover of the vinyl release.)

On lead single "Spite," he’s pulled between longing and resentment in the wake of the break-up over a bouncing guitar riff. Second single "Dispose of Me" finds Apollo heartsick and feeling abandoned as he laments, "It don’t matter if it’s 25 years, 25 months/ It don’t matter if it’s 25 days, it was real love/ We got too much history/ So don’t just dispose of me."

Elsewhere, the singer offers the stunning admission that "I would’ve married you" on album cut "Life’s Unfair." Then, on the very next song — the bumping, braggadocious "Against Me" — Apollo grapples with the reality that he’s been permanently altered by the love affair while on the prowl for a rebound. "I cannot act like I’m average/ You know that I am the baddest bitch," he proclaims on the opening verse, only to later admit, "I’ve changed so much, but have you heard?/ I can’t move how I used to."

More Omar Apollo News & Videos

Omar Apollo Embraces Heartbreak And Enters His "Zaddy" Era On 'God Said No'

How Danna Paola Created 'CHILDSTAR' By Deconstructing Herself

On Omar Apollo's New EP 'Live for Me,’ Limitless Experimentation Created Catharsis

Listen To GRAMMY.com's LGBTQIA+ Pride Month 2023 Playlist Featuring Demi Lovato, Sam Smith, Kim Petras, Frank Ocean, Omar Apollo & More

Omar Apollo On “Evergreen,” Growth & Longing

Given the personal subject matter filling God Said No — not to mention the amount of acclaim he earned with Ivory — it would be understandable if Apollo felt a degree of pressure or anxiety when it came to crafting his sophomore studio set. But according to the singer, that was entirely not the case.

"I feel like I wouldn’t be able to make art if I felt pressure," he says. "Why would I be nervous about going back and making more music? If anything, I'm more excited and my mind is opened up in a whole other way and I've learned so much."

In order to throw his entire focus into the album’s creation, Apollo invited Halm to join him in London. The duo set up shop in the famous Abbey Road Studios, where the singer often spent 12- to 13-hour days attempting to exorcize his heartbreak fueled by a steady stream of Aperol spritzes and cigarettes.

The change of scenery infused the music with new sonic possibilities, like the kinetic synths and pulsating bass line that set flight to "Less of You." Apollo and Halm agree that the single was directly inspired by London’s unique energy.

"It's so funny because we were out there in London, but we weren't poppin' out at all," the Halm says. "Our London scene was really just, like, studio, food. Omar was a frickin' beast. He was hitting the gym every day…. But it was more like feeding off the culture on a day-to-day basis. Like, literally just on the walk to the studio or something as simple as getting a little coffee. I don't think that song would've happened in L.A."

Poetry played a surprisingly vital role in the album’s creation as well, with Apollo littering the studio with collections by "all of the greats," including the likes of Ocean Vuong, Victoria Chang, Philip Larkin, Alan Ginsberg, Mary Oliver and more.

"Could you imagine making films, but never watching a film?" the singer posits, turning his appreciation for the written art form into a metaphor about cinema. "Imagine if I never saw [films by] the greats, the beauty of words and language, and how it's manipulated and how it flows. So I was so inspired."

Perhaps a natural result of consuming so much poetic prose, Apollo was also led to experiment with his own writing style. While on a day trip with his parents to the Palace of Versailles, he wrote a poem that ultimately became the soaring album highlight "Plane Trees," which sends the singer’s voice to new, shiver-inducing heights.

"I'd been telling Teo that I wanted to challenge myself vocally and do a power ballad," he says. "But it wasn't coming and we had attempted those songs before. And I was exhausted with writing about love; I was so sick of it. I was like, Argh, I don't want to write anymore songs with this person in my mind."

Instead, the GRAMMY nominee sat on the palace grounds with his parents, listening to his mom tell stories about her childhood spent in Mexico. He challenged himself to write about the majestic plane tree they were sitting under in order to capture the special moment.

Back at the studio, Apollo’s dad asked Halm to simply "make a beat" and, soon enough, the singer was setting his poem to music. (Later, Mustafa’s hushed coda perfected the song’s denouement as the final piece of the puzzle.) And if Apollo’s dad is at least partially responsible for how "Plane Trees" turned out, his mom can take some credit for a different song on the album — that’s her voice, recorded beneath the same plane tree, on the outro of delicate closer "Glow."

Both the artist and the producer ward off any lingering expectations that a happy ending will arrive by the time "Glow" fades to black, however. "The music that we make walks a tightrope of balancing beauty and tragedy," Halm says. "It's always got this optimism in it, but it's never just, like, one-stop shop happy. It's always got this inevitable pain that just life has.

"You know, even if maybe there wasn't peace in the end for Omar, or if that wasn't his full journey with getting through that pain, I think a lot of people are dealing with broken hearts who it really is going to help," the producer continues. "I can only just hope that the music imparts leaving people with hope."

Apollo agrees that God Said No contains a "hopeful thread," even if his perspective on the project remains achingly visceral. Did making the album help heal his broken heart? "No," he says with a sad smile on his face. "But it is proof of pain. And it’s a beautiful thing that is immortalized now, forever.

"One day, I can look back at it and be like, Wow, what a beautiful thing I experienced. But yeah, no, it didn't help me," he says with a laugh.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Photo: Arenovski

feature

Peso Pluma's Road To 'ÉXODO': The GRAMMY Winner Navigates The Consequences Of Global Stardom On New Album

"Fans really get to see the other side of the coin; there are two sides to me. It's darker, rawer," Peso Pluma says of his latest album 'ÉXODO'

Peso Pluma marked his musical destiny with a Tupac tribute tattoo in the center of his clavicle: "All Eyez On Me."

The Mexican artist, born Hassan Emilio Kabande Laija, doesn't remember exactly what year he inked his chest. He knows it was well before his debut in music. Those four words reflected Peso's irrefutable confidence that the world's eyes would eventually be on him.

The world's eyes are indeed on Peso Pluma. In less than two years, the singer achieved global fame by singing corridos tumbados, traversing a path never before trodden by a música Mexicana artist.

At 25, Peso Pluma is at the forefront of a new generation of música Mexicana artists that have successfully modernized traditional Mexican rhythms, such as corridos, by infusing them with elements from urban music and a hip-hop aesthetic. The weight of representing an entire genre and a country could be great for some. But pressure doesn't affect Peso Pluma; on the contrary, it motivates him to keep working to exalt his roots.

"We've come a long way, but we still have a long way to go. And that doesn't mean we have to slow down; it doesn't mean everything is over. This is the beginning of everything," Peso Pluma said in a TikTok video before a performance at the Toyota Arena in Ontario, Canada, a little over a year ago.

Out June 20, Peso's extensive new album ÉXODO seeks to cement his global star status further. Over 24 tracks, the singer continues to explore corridos tumbados and digs into his urban side via much-awaited collaborations with reggaeton and hip-hop icons. Among those big names is Peso's teenage idol, the American rapper and producer Quavo, as well as further afield collaborations with Cardi B.

"ÉXODO is a project I've been working on for over a year before we even won the GRAMMY. GÉNESIS was an incredibly special project, and I knew we couldn't make the same diamond twice," the singer tells GRAMMY.com in a written interview.

Peso Pluma's path to the global stage has been lightning-fast. While he started releasing songs in 2020, Peso will remember March 2023 as the month that propelled him into global mega-stardom. His collaboration with Eslabón Armado on "Ella Baila Sola" led him to become a household name outside his native Mexico.

The hit resonated with an audience eager for new sounds, accompanying social media videos and surpassing a billion streams on Spotify. "Ella Baila Sola" became the first Mexican music track to top the platform's global chart. On Billboard, it conquered No. 1 on the magazine's Global 200 chart for six weeks and reached the coveted No. 4 spot on the Hot 100 chart. The mega-hit took Peso Pluma and Eslabon Armado to make their Latin GRAMMY stage debut in November with an electrifying performance.

Another collaboration, "La Bebe (Remix)" with Mexican reggaeton artist Yng Lvcas, released a day after "Ella Baila Sola," also contributed to Peso Pluma's virality in a completely different genre, but one in which he feels comfortable: urban music.

Learn more: Peso Pluma's 10 Biggest Collabs: From "Bzrp Sessions" To "Ella Baila Sola" &"Igual Que Un Ángel"

As Peso Pluma gained traction with a global audience, his February 2022 single with Raúl Vega, put him, for better or worse, on the map in Mexico. The warlike content of "El Belicón" lyrics and video clip attracted attention for the way it allegedly promoted narcoculture.

Despite growing criticism, Peso Pluma remained tight-lipped regarding references to high-profile members of the Mexican drug trade, as well as drug use and trafficking. In a rare admission to GQ magazine, the singer explained this is a "delicate subject to talk about, but you have to touch on it with transparency — because it's the reality of things."

"In hip-hop, in rap, just like in corridos, and other urban music like reggaeton, it talks about reality. We're not promoting delinquency at all. We're only talking about things that happen in real life," the singer explained.

With the success of "El Belicón" and "Ella Baila Sola" under his belt, Peso Pluma released GÉNESIS in June 2023. Despite being his third album, Peso considers it his true debut in music.

"I didn't want to delete my previous albums [Efectos Secundario and Ah Y Que?] because they represent my beginnings," Peso told Billboard in a cover story published a few weeks after the release of GÉNESIS. In the same conversation, the singer said he saw himself winning his first GRAMMY and breaking more records.

Read more: 5 Takeaways From Peso Pluma's New Album 'GÉNESIS'

In February 2024, Peso Pluma did just that. He took home the golden gramophone for Best Música Mexicana Album (Including Tejano) — his first GRAMMY Award. This victory didn't weigh on him as he approached his next production. "It pushed me to want to create something different that the fans haven't heard from me before," Peso Pluma tells GRAMMY.com.

While GÉNESIS and ÉXODO may differ in substance, they share similarities beyond music. That both records pull from the Bible for their names is not a random occurrence; the opening book of the Hebrew and Christian Bible delves into the genesis of creation, while the Book of Exodus explores the themes of liberation, redemption, and Moses' role in leading the Israelites through the uncharted waters of the Red Sea.

"ÉXODO is the continuation of GÉNESIS, which was the beginning," Peso Pluma explains to GRAMMY.com. "ÉXODO means new beginnings, a new era for me. We are preparing for the next chapter, and that's what we are doing for Mexican music, paving the way, laying the groundwork for what's next because it doesn't stop here."

His "sophomore" album is divided into two discs: the first is corridos, and the second is urban. It also continues the line of collaborations, with twenty tracks where Peso Pluma shares the limelight.

"Some of my fans were craving música Mexicana, and some were craving urbano, and I wanted to give them everything while still staying true to myself and choosing songs and lyrics that spoke to me," he continues.

ÉXODO's disc one starts with "LA DURANGO," the album's fourth single, featuring Eslabon Armando and Junior H. In the record, he also invites collaborators such as Natanael Cano and Gabito Ballesteros for "VINO TINTO" and Mexican rising star Ivan Cornejo on the melancholic "RELOJ," among others.

For Side B, Peso enlisted heavyweights from the urban genre in the Anglo and Latin markets: Anitta in the steamy "BELLAKEO," Rich The Kid in the bilingual "GIMME A SECOND," and Quavo in the existential trap "PA NO PENSAR." Cardi B, Arcángel, Ryan Castro, Kenia OS, and DJ Snake complete ÉXODO's genre crossover.

In ÉXODO, luxury, drugs, alcohol, and women continue to take center stage in the lyrics, accompanied by fast-paced guitar-driven melodies and reverb-dense vocals. However, the production sheds light on the vulnerable side of Peso and explores the unexpected consequences of becoming globally famous.

"Fans really get to see the other side of the coin; there are two sides to me. It's darker, rawer," Peso says about the record.

In the songs "HOLLYWOOD" and "LA PATRULLA," for example, Peso details how this musical path keeps him up at night, as well as his aspirations, and how he remains the same despite his success.

Perhaps one of the deepest and rawest songs on the album is "14:14," a track inspired by the Bible verse 14:14 from the Book of Exodus, which, the singer explains, was fundamental amidst the turbulence he faced on the way to global stardom.

"[The] verse 14:14 says 'The LORD will fight for you; you need only to be still.' This verse couldn't be truer," Peso Pluma says. "Over time, I learned to really trust in this and believe that some things are not up to me and I should trust the process."

In the song — one of the few on the album without a collaboration — Peso references the challenges of his profession and how his faith has kept him afloat amid the vicissitudes. "Things from the job that no one understands/I hide the rosary under my shirt so I don't poison myself, so I don't feel guilty/because whatever happens, the Boss will forgive me," he sings.

In "BRUCE WAYNE," Peso Pluma croons about the passionate feelings his career arouses: "First they love you, and then they hate you/wishing the worst, envy and death," the song says.

The singer resorts to comparing himself to a superhero figure again. In an unusual twist, Peso crosses comic universes, moving from his now traditional reference to Spider-Man to one from the DC Comics world: Bruce Wayne, Batman's secret identity. A wealthy man, part of Gotham's high society, Bruce Wayne is known for transforming his darkness into power while remaining reserved and isolated.

"Everyone has two sides of them, even me," Peso tells GRAMMY.com. "Peso Pluma on stage is a high-energy person, someone who is powerful and dominates a show and isn't afraid of anything. And then there is Hassan, who's chill and more relaxed and who deals with all the realities of life."

During the year and a half it took him to complete ÉXODO, Peso Pluma had to deal with the diverse nuances of a global star's life, including a widely publicized breakup from Argentine rapper/singer Nicki Nicole, the cancellation of one of his shows in October 2023 after a Mexico drug cartel issued a death threat against him, and a media frenzy over his alleged admission to a rehabilitation clinic, the latest a rumor he laid to rest during a March interview with Rolling Stone for his Future of Music cover story.

"The reality is, all these days, I've been in the studio working on ÉXODO," the artist explained to Rolling Stone.

Most of 2023 was a successful balancing act for Peso Pluma, who combined touring, an album release, rare media engagements, two Coachella appearances, all the while developing another record. According to the singer, ÉXODO was created in Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and Mexico. "We go to the studio everywhere!" Peso says. "It doesn't really matter where we are; I love to get into the studio and work when we have free time."

Like GÉNESIS, ÉXODO will be released via Peso Pluma's Double P Records, of which he is the CEO and A&R. Much of the talent the Mexican singer has signed to his label took part in the album's production, and songwriting process.

"For the Mexican music side, I had the whole [touring] band with me; I like to have them involved in the process so that we can all give our input on how it sounds, discuss what we think needs to be changed, create new ideas," he explains.

Peso Pluma knows that echoing the success of 2023 is no easy task. He was the most streamed artist in the U.S. on YouTube, surpassing Taylor Swift and Bad Bunny, and was the second most-listened to Latin artist in the country, amassing an impressive 1.9 billion streams, according to Luminate.

Música Mexicana emerged as one of the most successful genres in 2023, witnessing a remarkable 60 percent surge in streaming numbers, adds Luminate's annual report, crediting Peso Pluma along Eslabon Armado, Junior H, and Fuerza Regida as part of this success.

Collaborations on and off the mic have undoubtedly played a significant role in the rise of Música Mexicana on the global stage. Peso knows that the key to continuing onward is teaming up with renowned artists inside and outside his genre.

"All of us coming together is what pushed música Mexicana to go global," the singer affirms. "We showed the world what Mexico has to offer, and now no one can deny the power and talent we have in our country."

Photo: Mark Seliger

interview

Feel Lenny Kravitz's 'Blue Electric Light': How The GRAMMY-Winning Rocker Channeled His Teen Years For His New Album

'Blue Electric Light' is a laser beam through Lenny Kravtiz's musical ethos: a rocking, impassioned and defiantly Lenny production. The Global Impact Award honoree discusses his first album in six years, and the flowers he's received along the way.

Lenny Kravitz is a vessel — a divining rod of creative direction.

"I just do what I'm told. I'm just an antenna. So what I hear and what I receive, I do," he tells GRAMMY.com. It's with that extra-sensory, spiritual guidance that Kravitz created his latest album, Blue Electric Light. "I just saw and felt this blue light — electric blue, almost neon light —radiating down on me."

Out May 24, Blue Electric Light is Kravtiz's first LP in six years and fittingly flits through the rocker's cosmology: Arena-ready booty shakers like "TK421" (the music video for which features the nearly 60-year-old unabashedly shaking his own booty), Zeppelin and Pearl Jam-inspired rockers like "Paralyzed," and shared humanity-focused groovers like "Human." There's plenty of '80s R&B sensibility throughout, giving Blue Electric Light a perfectly timed, timeless feeling.

It's as if Kravitz took a tour through his own discography, landing right back where he started: In high school. In fact, two of the album's tracks — "Bundle of Joy" and "Heaven" — were written when the four-time GRAMMY winner was still a teenager. While Kravitz's latest may lean into the sounds of his young adulthood, the album's underlying themes remain consistently spiritual, intimate and emotional. "My main message is what it has always been, and that is love," Kravitz told GRAMMY.com in 2018. And by staying true to himself and this message of love, Lenny Kravitz is thriving.

"I've never felt better mentally, spiritually, and physically. I've never felt more vibrant," he says today.

Kravtiz has also had a big year. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and, during 2024 GRAMMY week, was honored with the Global Impact Award at Black Music Collective’s Recording Academy Honors. At the ceremony, Kravtiz was lauded for his work with his Let Love Rule foundation, and his iconic discography celebrated in a performance by Quavo, George Clinton, Earth, Wind & Fire bassist Verdine White, and Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith.

Reflecting on his achievements, Kravitz remains humble. "Success is wonderful, but I only want success by being me and doing what it is that I'm hearing, as opposed to following something or a formula."

Ahead of releasing Blue Electric Light into the world — just a few days shy of his 60th birthday on May 26— Lenny Kravitz spoke with GRAMMY.com about revisiting his past, following his gut, and stopping to smell the flowers.

You haven't released a record in about six years. Why did you feel now was the time to put new music out, and what was inspiring you?

Well, it was just by virtue of what was going on. So I released [2018's Raise Vibration and], I toured for two years. Then COVID hits two and a half years [later]. It wasn't like I went away or wasn't inspired. I had a whole other year planned. I was going to tour for three years on that last album.

But [when] COVID happened, the world shut down and I got stuck in the Bahamas for a couple of years and a half. And so during that time I was just being creative. I [wrote the whole album] during that time and a little bit afterwards; [I wrote] just maybe two songs afterwards.

When I finished, then I had to figure out when I wanted to put it out and how. I did the Baynard Rustin song ["Road to Freedom" from the Academy Award-nominated film Rustin], and then I ended up pushing my album so I could fully promote the film and the legacy of Bayard Rustin.

Anyway, here we are. Everything happens in the time that it should, and I'm looking forward to putting this out and getting back on the road.

I read that this record was like an album that you didn't make in high school and it has this very young spirit. What took you to that place?

At the beginning of the pandemic, I released a book called Let Love Rule, and it ended up on the New York Times bestseller list. It was about my life from birth to the first album [1989's Let Love Rule], so around 24 years old. In this book, I spent a lot of time in my teenage years when I was developing. That came out at the beginning of the pandemic and I was doing a lot of press for it.

And I think because I was exploring that time so much when I was writing the book and then talking about that time so much when I was promoting the book, it just came out. And it was a time in my life that I never really celebrated. I never put music out at that time.

When I found my sound [on] Let Love Rule, all that material I was working on at that time got buried before. And so I just went to that place. I didn't plan on it, it just happened. In fact, two songs on the record ["Bundle of Joy" and "Heaven"] are from high school.

So it's a blend of where I am now and where I was then. And it's a really fun record and I had a really beautiful time making it. It's a celebration, and it's sensual and sexual and spiritual and social and it hits all the marks. I'm looking forward to getting out there.

You were obviously deep in your memories, and it sounds like you were probably listening to a lot of Prince in high school.

There's a lot of things. There's a blend of '80s technology and drum machines, and real instruments and synthesizers that I pulled out from then. During that time, yeah, I was listening to a lot of Bowie. I was listening to a lot of Prince, a lot of Rick James, a lot of just soul and R&B in general, and rock.

Are there any songs on the record that you are particularly proud of or that are really meaningful to you?

All of them. I hear it all as one piece. So it's just one flow of consciousness, but I'm really proud of the record.

One of my favorite tracks would be the opening track, "It's Just Another Fine Day in this Universe." I just think it's such a vibe and I love the way the chorus makes me feel. I think "Stuck in the Middle" is really pretty and sensual.

Speaking of vibes, when I'm listening to the record, it feels very hopeful. Is that generally how you've been feeling or how you go through the world these days?

I'm pretty optimistic. But now even more than ever, just on a personal level, I've never felt better mentally, spiritually, and physically. I've never felt more vibrant and I'm becoming more comfortable within myself in my skin and in my place.

I've learned that listening to that voice inside of me and sticking to what it is that was meant for me, my direction, has paid off and it feels good.

What do you attribute that growth and that deep comfort to, both personally and creatively?

Just [having] time to see the results. I'm blessed to live, to see the results of being faithful to what it is you've been given and told to do by the creative spirit, by God. People have always been trying to push me in different directions: "Do this, do that, follow this, go this way. This is what's happening right now." Follow the trends because they're looking at it as a business and they're trying to make money and have success.

Yes, success is wonderful, but I only want success by being me and doing what it is that I'm hearing, as opposed to following a formula that one thinks would work. Because once you follow that, you're already late, it's already happened. And I am not about being late.

I don't mind setting the tone or the trend and being early and not getting recognized for it at the time. Because I'm not doing it for the reason of receiving accolades or whatever. I'm doing it to be expressive and to truthfully represent myself.

I think that's a fantastic way to be. People come around eventually, right?

Yes. I've been reading reviews of my heroes back in the day, and I remember seeing Led Zeppelin reviews just ripping them to shreds. Led Zeppelin [are] praised [for] being classic and genius, but at one time they were s—, somebody said. So if you live long enough and you keep doing what you're doing, if you're doing the right thing and what you're supposed to be doing, you'll see that shift in people's opinions.

Not that that matters, but when you see it, it feels good because you know that you did it the way you were supposed to do it.

I hear a little bit of that defiance on this record too, that and the centering of your own truth — on "Human." Can you maybe tell me a little bit about that track and how it came to you?

Well, it just came like they all come. So I hear it and I think to myself, Okay, that's interesting. That has this real pop anthem, very uplifting feeling. [The song] speaks to us as spiritual beings having this human existence on this planet.

We are at our most powerful when we are authentic to ourselves. When you're authentic to who you are, you're shining and you represent what it is that you're meant to represent. And so the song just speaks on that, and really using this human existence to learn and to walk in your lane to reach your destiny.

In life since we've been born, we've been told what to do and how to do it: "Don't go this direction, go that way," and "No, don't do this, do that because this is the way it's done" or "This is what's safe." And we're all born with a gift; we're all born with a direction. And we don't all hit the marks because sometimes we don't accept what our gift is. Or we're too busy looking at others and what their gift is and we want what they have, and we leave behind what we were given. We go chase something that is not for us; it's that other person's calling.

So the more we shed all of that and really just walk in our lane, the better. And I am enjoying this journey of humanness and learning and growing, falling, getting up, climbing up the mountain, falling again, getting back up, continuing up. That's what it's about. It's not about how many times you fall... It's about how you get up and keep going. We're all here to live and learn and, hopefully, love.

I'm curious if the title of the record translates to this idea at all. Does Blue Electric Light manifest in any real way to you as a spiritual guide?

To me, it's a feeling. I just saw and felt this blue light — electric blue, almost neon light —radiating down on me, and that light is life. It's God, it's love, it's humanity, it's energy. And just metaphorically, that's what that represents to me.

Right on. To take it away a little bit from the existential and the spiritual, you just received the Global Impact Award at the 2024 GRAMMYs. You said you're not doing these things for accolades, but I'm curious how it felt to be recognized for this aspect of your work — something that isn't inherently musical that's a little more outside yourself.

Where I am in life right now is, if someone's going to hand you flowers, then stop, smell them and enjoy them. And that's what I'm doing.

I make my art because I make my art and for no other reason, but when handed these flowers, I'm appreciative. I'm grateful, and I will enjoy them because I spent my whole career not doing that. I was always moving so fast and [was] not only concerned with the art and moving forward, that I didn't enjoy those moments when you get awards or things. So I made a promise to myself years ago, moving forward when the flowers are delivered, that I will stop and smell them, take a moment, breathe, and then move forward.

And that's what I'm doing, because every day of life is beautiful. And when you can celebrate, why not celebrate?

Amen to that. It's that presence of mind and spirit that you have been talking about this whole time and seems to have flowed through your artwork as well. With regard to the work with your Let Love Rule foundation, are there any projects that you would love to tackle next?

There's so many. From some things I've been doing with friends, like building certain foundations in Africa with someone that's on the ground there, doing it firsthand with orphanages in schools, to the medical situation in the Bahamas, to continue providing medical and dental care for free to the people so they can have their basic health issues taken care of.

And then also working with kids in the arts and helping to give them a foundation to work from. These are things that I'm interested in.

Photo: Jason Kempin/Getty Images

list

5 Ways Sheryl Crow Has Made An Impact: Advocating For Artist Rights, Uplifting Young Musicians & More

As the Recording Academy honors Sheryl Crow at the 2024 GRAMMYs on the Hill Awards, take a look at some of her biggest contributions to the music community and other social causes.

Sheryl Crow may be a nine-time GRAMMY winner and a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee, but her legacy extends far beyond her music. She has dedicated her career to advocating for her fellow artists and social causes close to her heart — and that's why she's one of the honorees at this year's GRAMMYs on the Hill.

On April 30, Crow will be honored at Washington's premier annual celebration of music and advocacy alongside Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) for their bipartisan spearheading of the Save Our Stages Act and the Fans First Act. The "All I Wanna Do" singer called receiving her GRAMMYs on the Hill award "a tremendous honor…because protecting the rights of creators is more important now than ever before."

Helping creators thrive has long been part of Crow's career. She has made it her lifelong mission to support other artists and stand up for causes she believes in, from co-founding a pioneering advocacy group for musicians to supporting the music program at her alma mater.

Below, check out five ways Sheryl Crow has exemplified advocacy within the music industry — and beyond — over the course of her career.

The 2024 GRAMMYs on the Hill Awards is sponsored by City National Bank and benefits the GRAMMY Museum.

She Co-Founded The Recording Artists' Coalition

In 2000, Crow and fellow GRAMMY winner (and previous GRAMMYs on the Hill honoree) Don Henley founded the Recording Artists' Coalition. The organization's mission is to represent artists, defending their rights and interests and challenging unfair industry practices.

One of the advocacy group's first major legislative wins came in its founding year, when then-President Bill Clinton signed a law repealing The Works Made for Hire and Copyright Corrections Act. The provision had designated musical recordings as "works for hire," thereby taking away many artists' rights to royalties.

In 2009, the Recording Artists' Coalition aligned with the Recording Academy to continue the organization's work as part of the Academy's Advocacy and Public Policy office. (Crow is also a member of the Music Artists Coalition, which was founded in 2019 and has a similar mission to protect artists' rights.)

She's Sounded The Alarm About The Dangers Of AI

Crow released her eleventh studio set, Evolution, in March and tackled the topic of artificial intelligence head-on via the LP's ominous title track. "Turned on the radio and there it was/ A song that sounded like something I wrote/ The voice and melody were hauntingly/ So familiar that I thought it was a joke," she sings on the opening stanza before questioning, "Is it beyond intelligence/ As if the soul need not exist?"

The prolific singer/songwriter explained her decision to put her concerns about AI's threat to creativity, songwriting and even artists' ownership over their own voices in an interview on the podcast Q with Tom Power earlier this month.

"It terrifies me that artists can be brought back from the dead; it terrifies me that I can sing to you a song that I had absolutely nothing to do with and you'll believe it," she said. "And so I'm waiting to see if the best of us will rise up and say, 'This cannot be' 'cause our kids need to understand that truth is truth. There is a truth, and the rest of it is non-truth."

Later in the wide-ranging conversation, Crow added her insight into how technology, social media and the modern streaming economy are all negatively impacting listeners' relationship to music as well. "We need music that tells our story now more than we've ever needed it," she urged. "And yet, we're going to bring in technology — already, algorithms are killing our ability to even not only listen to a whole song, but to experience it at a spiritual level."

She's Championed Racial Equality In The Music Business

Amid the summer of marches, demonstrations and other civil actions in the wake of George Floyd's tragic 2020 murder, Crow used her platform and privilege as a white musician to help shine a light on the plight of Black musicians fighting for equality within the music industry.

"I stand in solidarity with the Black Music Action Coalition in their efforts to end systematic racism and racial inequality in the music business," she wrote in a 2020 social media post. "It is impossible to overestimate the contribution of Black people in our industry; Black culture has inexorably shaped the trajectory of nearly every musical genre. Most artists, myself included, simply would not be here without it. The time to acknowledge this fact is long overdue."

Crow went on to call for the music business to become a "shining example of reform to other industries." She added, "Acknowledging and making amends for both historic and ongoing inequalities, and creating a path forward to ensure they never occur again, is our highest calling."

She's A Charitable Powerhouse

Crow has long made philanthropy a central priority in her life. Along with supporting the Recording Academy's own MusiCares initiative, the "Steve McQueen" singer has backed and partnered with a veritable laundry list of non-profit organizations including, but not limited to, The Elton John AIDS Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the World Food Program, ADOPT A CLASSROOM, Pelotonia, the Delta Children's Home, Stevie Van Zandt's TeachRock Artist Council and more.

Additionally, she's spoken out countless times about gun violence, Medicaid expansion, women's health, mental health, the death penalty, LGBTQ+ rights, and a host of other issues, particularly affecting Tennessee, where she now calls home.

The "Soak Up The Sun" songstress has also used her musical talents to give back over the course of her career. In fact, just weeks before releasing Evolution, she contributed to the star-studded 2024 re-release of Mark Knopfler's 1983 debut solo single "Going Home: Theme of the Local Hero" to raise money for the Teenage Cancer Trust.

She Supports Music's Next Generation

A proud alumnus of the University of Missouri, Crow holds a degree in music education and has continually given back to her alma mater's music program in an effort to support the future generations of music makers.

In 2015, Crow headlined her own benefit concert for the Mizzou School of Music's fundraising campaign, which led to the choral performance and rehearsal hall inside the campus' Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield Music Center being rechristened Sheryl Crow Hall in early 2022.

As she's achieved veteran status in the music industry, Crow has also made a particular point to uplift and champion young female artists. In 2019, she partnered with TODAY for its "Women Who Rock: Music and Mentorship" series, and in 2020, took part in Citi's #SeeHerHearHer campaign to boost representation of women in music. More recently, she has touted Taylor Swift as a "powerhouse" and offered career advice to her now-frequent "If It Makes You Happy" duet partner, Olivia Rodrigo.

Whether she's inspiring young women or advocating for music creators of all kinds, Sheryl Crow has already left an indelible mark on the music industry. And if her previous efforts are any indication, she's not stopping anytime soon.