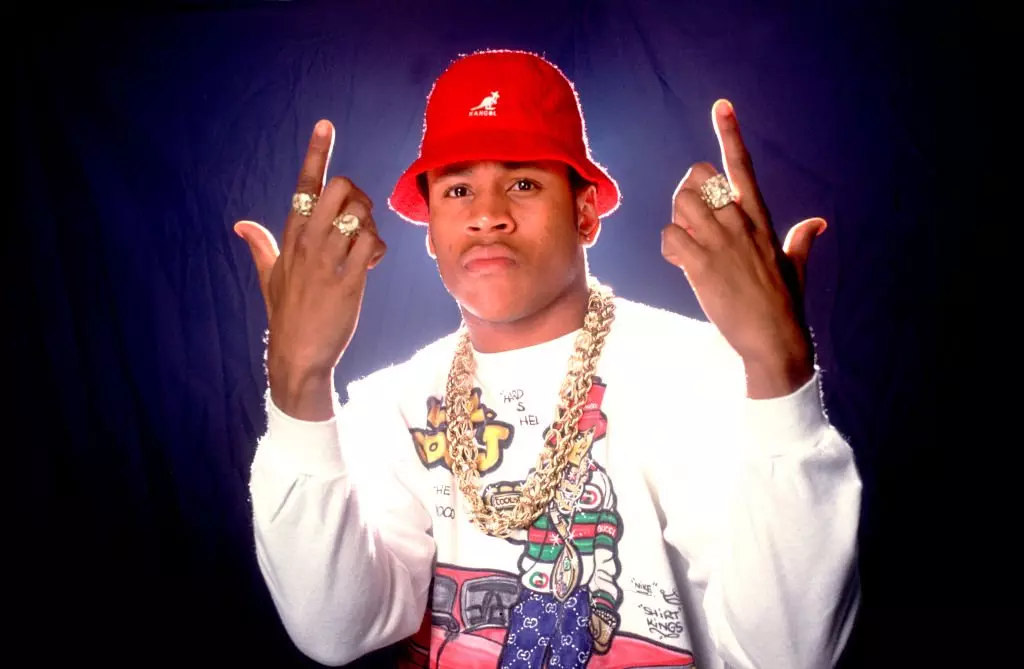

GloRilla knows a thing or two about the power of social media. The Memphis native’s rise to rap stardom began in May 2022, when her breakout song with HitKidd "F.N.F. (Let’s Go)" went viral on TikTok. For some artists, a viral hit single is the ultimate goal — but for Glo, it was only the beginning.

Within the next few months, she signed to Yo Gotti's Collective Music Group and hit the studio to finish recording her EP, Anyways, Life’s Great, which includes the single "Tomorrow 2" featuring Cardi B — her rap hero-turned-friend. Last November, their performance at the American Music Awards brought the house down. One month prior, Glo won Breakthrough Hip-Hop Artist at the BET Hip-Hop Awards, then took the stage to perform "F.N.F." as rap icon Lil' Kim and other female emcees danced and rapped along from the audience.

GloRilla's hard-hitting flow and contagious energy has attracted additional co-signs from Mary J. Blige and Nicki Minaj, and earned her a nomination for Best Rap Performance at the 2023 GRAMMYs. At the awards, Glo will be up against heavy hitters like Doja Cat, Kendrick Lamar, Lil Wayne, DJ Khaled, Jay-Z, Gunna, and Future.

Born Gloria Hallelujah Woods, the 23-year-old rapper's Memphis roots shine in her crunk-infused songs, which touch on everything from break-ups and fake friends, to sex and turning up at the club. Glo also embeds hard-learned lessons throughout her EP, pushing back against critics and fairweather friends on "Out Loud Thinking" while highlighting the importance of prioritizing your own needs and pruning toxic people on the slow jam "No More Love."

For fans, part of Glo's appeal — outside of her music — is her relatability. She just wants to have a little fun, build a long and lucrative career and take care of her loved ones.

GRAMMY.com caught up with GloRilla to discuss her rise to fame, writing process, dream collabs and the advice she received from Cardi B.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Congratulations on your GRAMMY nomination. How did you hear about the nod?

I was just getting off the plane in L.A. I didn't believe it until I got on Twitter and I saw them saying it. I couldn't believe it for a minute. I thought they was lying.

You took the music world by storm last year. You released the song of the summer, dropped an EP, collaborated with Cardi on "Tomorrow 2," with Ciara, and Summer Walker on the "Better Thangs" remix and won a BET Hip-Hop Award within the span of a few months. Which moment meant the most to you out of everything you experienced last year?

I just can't single out one thing. A lot of people don't get to experience this, so everything is just super special to me.

After you dropped "F.N.F," when did you realize your life was going to change?

Once the song went viral on all the different social sites and different celebrities started reaching out to tell me they liked it.

Anyways, Life’s Great is an incredible debut. How long did it take you to write and record the EP?

A few of those songs I had recorded before I blew up: "Nut Quick," "PHATNALL" and "Out Loud Thinking." It didn't take long to record the rest of it. Once I'm in the studio, and I get the vibe, it just is what it is at that point.

At first, I would write my songs at home and pay for two hours of studio time. But now I can write in the studio.

Do you wait for dedicated studio time or are you always writing?

I could be doing anything. I could be watching TV and they can say something and it’ll give me an idea and I’ll jot it down in my notes. Or I can be at the airport and see something, and it’ll give me an idea. Then at the studio, I’ll gather all the notes I wrote together and see what sounds good on what beats.

The beat for "F.N.F" was originally meant for Megan thee Stallion. When that didn’t work out, Hitkidd offered it to you, and you wrote it pretty quickly. Are you usually a fast writer or was it something about that particular beat that inspired you?

I actually listened to the beat all day, and I couldn't come up with nothing. When I finally pulled up to the studio, I had to get a blunt, so I could think of something. Soon as I got done smoking, I wrote it so fast.

Your "Tomorrow 2" collab with Cardi was an instant hit. It was such a perfect pairing: two talented, genuine, energetic emcees who are unapologetic and own their space. How did that collaboration come about?

My team had hit her up, Gotti and them. I didn't know they had did it. I texted her one day to get on another song I had but she said, "I’m already doing ‘Tomorrow.’" I was shocked, and I was so excited. Then she had sent me the clip of her verse. And when I heard it, I was like, "Oh my God, Cardi. What got into you?"

I felt the same way when I heard it. She went hard. How was it performing at the American Music Awards with her?

Great, I love Cardi so much. Like, I know ain't nobody perfect. But to me, she's just so perfect.

Did she offer you any career advice?

The best advice I got from Cardi was just to stay focused, keep going hard and don’t stop.

You grew up in a big Christian family — you're one of 10 kids. Was music always playing in the house?

Yeah, I used to listen to gospel music all the time. I liked Yolanda Adams, Deitrick Haddon, Kirk Franklin, and Tamala Mann. But we also watched "106 & Park" and "BET Countdown."

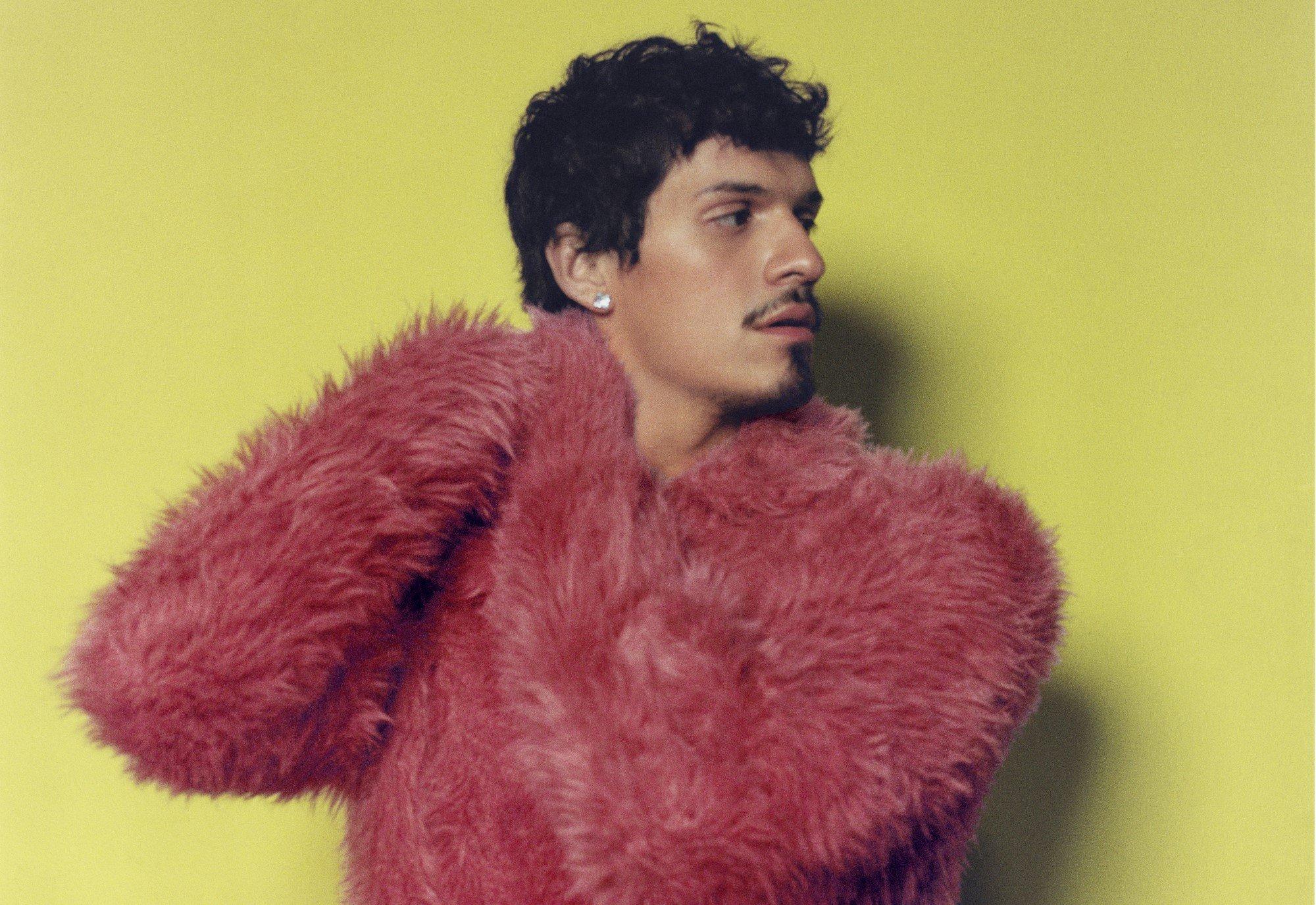

Your styling is always on point and makes me want to step my own fashion game up. What inspires your looks?

I liked Aaliyah and Left Eye growing up. I loved how they dressed. I really just be on some new-school version of Aaliyah.

I saw a clip of you singing "Bet On It" from High School Musical and it made me wonder if there are any other artists or songs that people would be surprised to find that you like.

I really like Ariana Grande, and I'm in love with Miley Cyrus.

You’re a big Beyoncé fan, and she’s one of your dream collabs. Who else would you love to work with in the future?

There’s a lot of people I want to do songs with that I’m a fan of. But my top two that I'm extremely obsessed with is Beyoncé and Chief Keef. I want to work with Drake and Lil Wayne, too.

I've noticed that you do not hesitate when you want something. You just figure out a way to make it happen.

All it takes is faith and manifestation. One, you actually got to put the work in and have discipline and know that it is there. You just gotta work for it. I tell everybody that's gonna get you a long way. Manifesting and having faith and actually working and reaching toward that goal. I don't feel like it's nothing you can't accomplish if you have your mind set to it and you don't ever stop or give up on it.

Your music is full of these nuggets of wisdom that may help people learn how to navigate different life challenges. Would you ever consider writing a self-help book?

I was actually talking about that with one of my friends.

Alongside that, I could see acting in your future too. I think about the City Girls working with Issa Rae down in Miami on "Rap S—" and I could easily see a show about your come-up set in Memphis. Is Big Glo the actor something we can look forward to?

Yeah, of course. Before I got into music, I wanted to act. I love Meagan Good, Taraji P. Henson. Those are my top two. I like Kevin Hart, Idris Elba. It’s a lot of people. I like Regina Hall.

You’re heading out on a 16-city solo tour soon. How are you preparing for tour life? Do you have to learn any choreography?

Yes. I've been going to practice a lot. I've been doing good though. We gonna put together a good show on the tour. We gonna turn up. I actually like doing choreography.

Were you into choreo growing up?

Yeah, I was a majorette, and I still can't dance. But I like to learn, and once I get it down pat, and I know how to do it, I'll be like, "Yes!" But I got two right feet. I don't got two left feet. [Laughs.] So that's why I like learning. ‘Cause when I just be on the stage rapping, it can get boring if you just walking around, you know? They wanna see you pop out with a little somethin’ somethin.’

Who are you taking on tour?

Gloss Up, Slimeroni, K. Carbon, and Aleza.

After the tour, do you have any plans to release an album or another EP in 2023?

Most definitely. I'm changing it up. I'm gonna have different guys on it.

Listen: All Of The Rap Music 2023 GRAMMY Nominees In One Playlist

.jpg)

.jpg)