Photo: Gaelle Beri/Redferns via Getty Images

feature

How Deafheaven's 'Sunbather' Changed Our View Of Metal

Released in 2013, 'Sunbather' is a deeply personal album whose myriad influences drew both critique and mass appeal. GRAMMY.com revisits Deafheaven's landmark album and the way it upended views about black metal.

In the winter of 2013, guitarist Kerry McCoy and vocalist George Clarke — founding members of black metal innovators Deafheaven — went into the studio to record what would eventually come their breakthrough album Sunbather. Armed with home-recorded demos and high ambitions, they were ready, but they were scared as hell.

"I just wanted to make sure that the record was like... not perfect... but like, really on point," McCoy said in a 2013 promo video.

Although their debut album, 2011's Roads to Judah, had succeeded in raising a few eyebrows, Deafhaven were still figuring out who and what exactly they were. Clarke and McCoy were still living in San Francisco, still working terrible jobs, and doing whatever they could to pay the bills, and music was their only way out of this life. They wanted their next record to be on point simply because it had to be.

On June 10, their savior came into the world. An album of beautiful contradictions,Sunbather became one of the most important rock releases of the decade. Nothing about the album — from its layered arrangements that blend black metal with post-rock, pop, and shoegaze, to its pink, sun-kissed album art — fit neatly into what black metal (or any genre for that matter) was considered to be.

Along with new drummer Daniel Tracey, McCoy and Clarke reached for the heavens from within their own personal hell. And that's what Sunbather does so well: finding light within the cracks of darkness. From the epic opener "Dream House" to the gorgeous, knee-buckling closer "The Pecan Tree," the album is in constant motion, shifting back and forth between dreamy post-rock, immense nuclear explosiveness, and cathartic payoffs. Its songs move with a churning fluidity, building to a climax before they crumble again. Clarke's sharp, piercing howls along with McCoy’s cascading avalanche of guitars and Tracey's rapid-fire bursts of drums together created an energy so grand, it could move mountains.

At the heart of Sunbather is a deeply personal album told from the perspective of people yearning to live in peace. Lyricist Clarke would gaze into San Francisco's many penthouse apartments on his walk home after a long day at work, wondering what it would be like to live obviously and carefree. On the album’s title track, a Cohen-esque narrator drives through an affluent neighborhood, only to become more depressed at the sight of a young woman lying on the grass among the green trees.

While the lyrics are mostly indecipherable on record, if you take the time to look up what’s being said, you’ll find that Clarke’s words grapple with insecurity, the ability (or inability) to love, and whether there is a better life out there waiting. The album is vulnerable, romantic, and personal. As Clarke put it in 2013, "Sunbather is like ripping pages out of my journal."

With its shrieking vocals and thrashing guitars, black metal is raw, brutal, and by nature, not easily accessible. Born out of Norway in the 1980s, bands like Mayhem, Emperor, and Darkthrone toiled in dark, gruesome imagery and some questionable values. Their music sounded as if it came straight from the depths of hell. They sing about war, destruction, and death; the loud, intense music is meant to invoke a sense of dread. It’s not for the faint of heart, and its bands can be quite intimidating. For devotees, that’s part of the appeal. Being in black metal means surrounding yourself in the darkness; you either get it, or you don’t.

At face value, it makes sense that Deafheaven would be categorized as black metal. Their music can be just as intense as any other band in the genre, but the emotional depth and nakedness on Sunbather is part of what separates Deafheaven from their peers. It’s a different kind of intensity that leaves room for warmth and hope, and ultimately broadened their appeal beyond the black metal scene.

They bared their souls in a way most metal bands would not dare, choosing not to hide behind corpse face paint or technical prowess. The members of Deafheaven didn’t play the part of a stereotypical Scandinavian metal band: They didn’t have long, flowing hair; they wore skinny jeans and Vans sneakers. Their singer could’ve been a model in a different life, and because they were so clean-cut, Deafheaven were accused of being hipster posers who didn’t make "real" metal music.

A "true" black metal band would not reach for the rafters like U2 as they do in the "Dream House" finale, nor would their interludes call to mind Wilco or Oasis. A real metal group wouldn't listen to Drake, an artist Deafheaven has admitted to being fans of and whose music touches upon similar themes.

As a result Deafheaven were immediately cast as outsiders in their own scene.

Whereas the scope of Sunbather might have displeased hardcore metalheads, the album's accessibility inadvertently opened new doors for black metal, a genre traditionally against any sort of evolution or deviation. By making heavy music that reflected the music they consumed, Deafhaven became one of the first bands to dismantle genre-gatekeeping.

Indeed, Sunbather is just as indebted to My Bloody Valentine and Explosions in the Sky as it is Emperor’s black metal classic In the Nightside Eclipse. Sunbather used black metal as a vehicle to amplify a vast palate of emotion.

For its wide appeal and depth, Sunbather received significant acclaim in 2013 from all ends of the critical spectrum. The album appeared at the top of numerous year-end best of lists, and has since been named one of the 100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time by Rolling Stone.

In an era before streaming allowed easy access to a myriad of musical styles, genre-bending albums like Sunbather were still relatively novel, and even more so in hard rock circles. Sunbather provided the blueprint for bands like Turnstile, whose latest album GLOW ON has seen them to outgrow the similarly cloistered hardcore scene they were brought up in. But Deafheaven's influence can be heard broadly, through the work of artists as diverse as Bartees Strange, Lil Yachty and Taylor Swift — each of whom have boldly embraced genre fluidity.

In the 10 years since Sunbather, Deafheaven have become one of metal’s most vital bands, and continue to change the way we think about the genre. The band have continued to shape-shift with each album release: 2015’s New Bermuda saw them lean more into thrash metal, while 2018’s Ordinary Corrupt Human Love was a bit sunnier and slightly more indebted to '90s alternative rock. Their latest record, 2021's Infinite Granite, eschewed black metal all together in favor of a gentler, dreamier sound that has more in common with the Smiths than Cradle of Filth.

While Deafheaven continues to evolve and move further away from their black metal roots, Sunbather remains their crowning achievement. On that album, they somehow managed to blend oil and vinegar, creating a concoction of genres that remained true to their vision. It couldn’t have been more on point.

Foo Fighters’ Road To ‘But Here We Are’: How The Rock Survivors Leaned Into Their Grief

Deafheaven

Photo: Robin Laananen

news

George Clarke On Deafheaven's New Album 'Infinite Granite,' Finding His Voice & Breaking Out Of Underground Memeification

When Deafheaven got huge, a swath of black metal purists went to war while diehard fans exalted them as be-all-end-alls. But their most forward-thinking album yet, Infinite Granite, is—as singer George Clarke insists—"just a record"

Album art should ideally describe what's inside in some way, but Deafheaven's latest is unique in that it literally shows music. What may look like a grainy Voyager photo of Neptune in its indigo immensity is actually the first minutes of the opening track "Shellstar," processed through a visualizer and photographed in long exposure. To singer George Clarke, the resultant orb of blue specks on coal-black connotes "space or infinity, but it's also quite embryonic... almost like a place of birth."

The band is also unique in that they treat themselves as solely musicians. In a field of swollen egos, this isn't a given. Ever since 2013's Sunbather, which inspired outsized reactions from zealots and haters alike, the GRAMMY-nominated five-piece—Clarke, guitarists Kerry McCoy and Shiv Mehra, bassist Chris Johnson and drummer Daniel Tracy—has made a point to simply write the best music they can and not make a big deal out it. In a hailstorm of memes about crew-cuts and delay pedals and weeping in awe, Deafheaven simply worked hard.

"We're just five dudes who like catchy guitars and fast drums," McCoy told Rolling Stone somewhat tersely that year. "It's not anything special. What we do is just really, really simple."

Now, with their new album, Infinite Granite, which arrives August 20 via Sargent House, they get to fully enjoy the rewards of not believing their own hype. In what's already the primary talking point surrounding the album, Clarke doesn't scream throughout 85 percent of it, but croons. On advance singles "In Blur," "Great Mass of Color" and "The Gnashing," he displays just how hard he worked to not sound tentative, or coached, but confident—as if he had sung since the very first record.

In a wide-ranging interview with GRAMMY.com, George Clarke opens up about the cosmic and literary inspirations behind Infinite Granite, his creative development over the last year and a half and why, in the end, this is "just a record" and nothing more.

What's your life been like for the past year and a half?

It was fine, to be honest. The tour cancelations were a bit of a hit, but we were able to do this makeshift live record in-studio featuring songs we were going to play that year. That came together quickly and we were able to do that, which felt good. We were at the end of our cycle for Ordinary, so we had it easier than a lot of people did. We were able to settle into a writing period, so we started taking the necessary steps to get that done.

Which, of course, had its own difficulties, because we were very conscious of everything happening and we wanted to be as safe as possible. People were getting tested all the time and we were traveling to different studios with masks and all that, which kind of heightened the atmosphere of it, I think, and made things a little more difficult. But overall, it was good. We used the period to try to be creative and not waste what we saw as an opportunity.

Once the record finished, I went to New Zealand and lived there from January until about the beginning of May. Then, I've been back in L.A. since then, just kind of rolling out the album. I came back to start this whole experience, which has been really nice.

Was it a shock to the system after riding around in a van or bus for 10 years?

Yeah, definitely, especially this past year. We were spending a lot of time with each other. We worked on this record longer than any previous one, so we were together a lot, and that was great and felt very natural. But it was interesting not being on the road. Being at home for that amount of time is not something any of us are used to. That has increased throughout 2021 because we're not working on the record and not seeing each other as much. We're all eagerly anticipating that side of things to pick up again.

Did the other guys make it through OK, financially or otherwise?

Yeah, they did. That was one of the first things that happened: We had an emergency meeting and looked at all our accounts. We keep things for savings and this sort of thing. We were thankfully able to budget throughout the year so everyone could be as comfortable as possible. And, of course, unemployment as well.

Thankfully, everyone is alright, but there have definitely been times of stress. Everyone has picked up side work here and there, but that's also just in an effort to keep busy, I think. That was the other thing: The extreme boredom, the extreme idle feeling of the last year got to people a little bit.

I'm not sure how other journalists will receive Infinite Granite, but to me, it stands out from the rest. Hearing you let loose with a scream at the end—rather than screaming all the way through—gave me a feeling I hadn't gotten from any past Deafheaven record.

Thank you. I have no idea either! When we were making it, it wasn't a thought. There were jokes and things like that, but we weren't really consciously considering it. And then after the record was finished, we started to. I think that's what happens: Your head kind of clears and you sort of leave the cave and you're like, "Oh. How are people going to hear this? This actually might be quite interesting, to see what the reaction is."

I will say that we spent a lot of time on it and I think there's a lot of detail in it that wasn't necessarily present in our other albums. I think we really wanted to work more with nuance this time around.

One thing that's always struck me about Deafheaven is that you guys would open for Lamb of God or Slipknot—and then go play with non-heavy artists like Slowdive or Emma Ruth Rundle—with something of a smirk. I don't sense that you guys had existential crises along the way.

I think that early on, we simply saw that we could do both.

Just by getting the opportunity to do both, we saw that as an advantage, like an interesting position that not a lot of people were able to have. Say another band had the same position: They'd be like, "Oh, even if we can do both, we want to shy away from this and only work within this kind of thing. I don't know how an indie audience is going to respond to this, so we should always just take the Lamb of God opportunities," or vice versa.

"I think what we do is serious music, but you don't want to always feel like you have to go to battle for your art."

We would rather say yes to everything. It's all part of the greater experience of playing music like this. I think there's maybe a bit of a smirk, but it's just like an acknowledgement of how strangely unique it all is. Like, "That does work!" or "We can make it work!" and there's something fun about that. That's part of what makes what we do fun, and we have to have some of that.

At the same time, we kind of had to defend ourselves throughout our whole career, and that's a little tedious. At that point, it starts to get a little self-serious. I think what we do is serious music, but you don't want to always feel like you have to go to battle for your art.

Back in the Sunbather era, I also sensed some bemusement at your haters, like, "We're not really black metal? They're making memes about us? Fine, great, I don't care."

I was kind of surprised by it, really: People really care! Sometimes that's funny. That's the honest attitude that we have maintained, and, in a way, have had to maintain. It gets a little unnerving when people tell you, "I think this is the greatest thing ever made," or "This saved my life."

It's not just the negative things. It's quite often the very true and positive things that make you have to recalibrate and be like, "Look, everyone, while I'm glad people are having an emotional reaction to the music—and while I want them to, and that's part of the intention of making it—it also needs to be stated, for good and for bad, however you choose to see it, there are just songs. We're just people in a room trying to be creative and not be bored."

Your music is often very heightened and does elicit extreme emotional responses. Have you ever felt invaded by fans or like people were getting creepy about it?

No, no. I've never really felt that. It's always been a lot of love. It's just good to be objective sometimes, I think. Like I said, that recalibration. It's just reminding everyone that, at least from our standpoint, this is just something that we're doing.

That record in particular [Sunbather], I was really surprised at how people gravitated toward it and how it became such a conversation piece, almost like a weird moment in the subculture. From that kind of came what you were talking about earlier, where it's like, "Man, we're like memes. Oh, funny. People are really invested."

And from it came so much good, so I'm thankful that we're able to experience that, but it was funny.

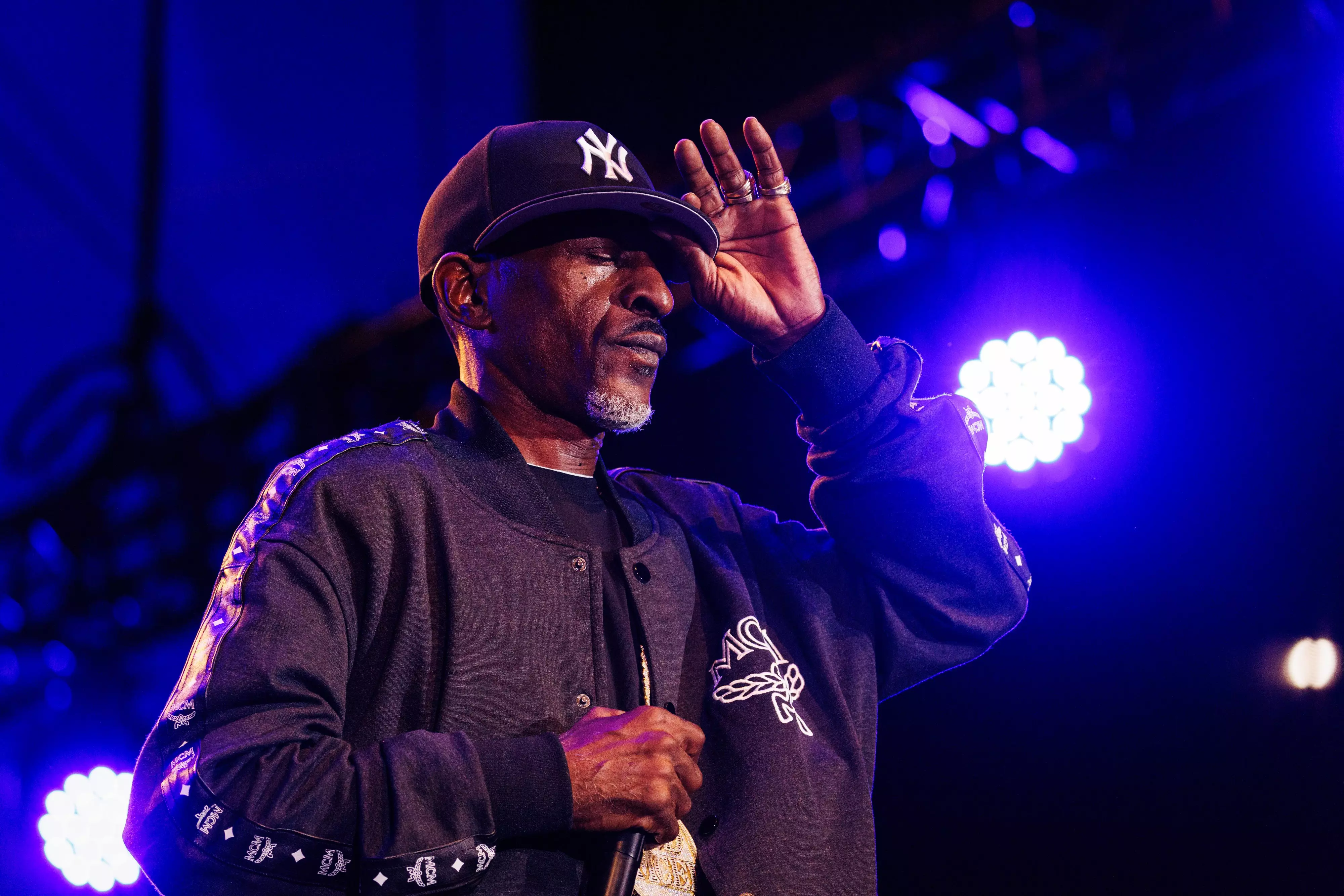

Deafheaven's George Clarke performing in Oslo in 2018. Photo: Avalon/PYMCA/Gonzales Photo/Per-Otto Oppi/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Was there a moment where the irritation of needing to defend yourselves began to loosen up and you guys could just be a rock band?

Yeah, yeah. We talked about this a little bit during Ordinary amongst ourselves. At the time, we were feeling really alleviated from not being so centered in the conversation.

I think what it was was we just stuck around long enough. Perhaps, if we had gone away after Sunbather, we would always be this thing, but because we continued forward making music we wanted to make and touring and not really making a big deal out of it, I think people are like, "OK, I can focus on something else."

When we were first coming out, there were a couple of different "controversial" bands that have all, I think, outgrown that. [Hunter Hunt-Hendrix] of Liturgy being another one, who just does her own thing and expands with each record. I think perhaps it is just a time thing, but regardless of the reason, yeah, it's freeing to be in that position. And I still feel that freedom.

Even if it is still a conversation—us at large—I don't see a ton of it.

What prompted the move from Anti- to Sargent House for Infinite Granite? I imagine you merely fulfilled your contract, but I don't want to presume.

Yes, that is it—we fulfilled the contract. I love Anti- and we had a very good experience with them.

Since we knew we were going to be working with Justin [Meldal-Johnsen] fairly early on, there was an idea with this record to expand the musical palette and expand the production and, along with that, expand those budgets while simultaneously shrinking the business side and taking more control over it and working closer with Sargent House in a more symbiotic way, because from a management side, we've been together so long.

There was an idea to kind of bring everything home while we were making this sound and delivery and art and all that much more expansive.

Since you guys have been with them forever, it doesn't strike me as downsizing, but consolidating.

That's exactly it. It's just putting everything under a smaller umbrella and having more control. Not to expand on it too far, but there was this idea that people would think the aspirations for this record were more commercial.

I think on a subconscious level, sticking with Sargent House and, in fact, even leaving Anti-, would be kind of a silent response to that curiosity. Just being like, "No, this is purely an artistic move, and we want to do it with the people we've known and gotten to trust over the past decade.

Were people starting to think you were reaching for pop appeal?

I'm not sure if that's a widespread idea, but it was in the realm of what people could be thinking. That's something I anticipated and was conscious of. I think it's an interesting optic to pursue, I guess, this bigger, more rock sound while honing everything in on the business side of things.

When I first saw the album cover, I figured it was a NASA photo. Then I looked at it more closely and realized it wasn't, and then I read that [Touché Amoré's] Nick Steinhardt designed it.

It's funny: Nick and I spent months talking about the album. I sent him the lyrics and said, "This is how I'm feeling about it," and so on. Blue was present very early on, and both of us, honestly, were envisioning this sort of blue mass. We both had this idea of spherical immensity—a strange, strong spherical image.

From that, he basically created an MP3 visualizer that rotates 360 degrees as the song plays. It's made up of all these dots and their movement shifts with the song, and then, as the soundbar does its 360-degree rotations, we took long-exposure photographs of those rotations. The cover is actually the first couple of minutes of the first song, and each track has its own corresponding orb that's made of the music.

We were thinking about concept albums and talking about how artwork of conceptual records always reflects the lyrical content. For this, we wanted to kind of flip that on its head and have artwork that literally was a visual embodiment of what was happening sonically.

He did some tests and made maybe 300 or 400 of them, which all looked fairly similar. We just kind of went through and I was really struck by the one that made it to the cover. To me, not only does it have a kind of idea of space or infinity, but it's also quite embryonic. I look at it almost like a place of birth.

Did the track title "Neptune Raining Diamonds" grow out of it?

They were kind of separate ideas. I heard the guys making "Neptune Raining Diamonds" and, to me, it just kind of sounds like that. I was doing some reading and there was a National Geographic article on how Neptune rains diamonds. It was talking about all the atmospheric pressure that makes this effect. I thought it was really interesting and, to me, it's what that track sounded like.

Can you imagine anything more visually splendorous than that?

When I saw the headline in the article, I thought the same thing! I was like, "Man, that visual is incredible." I can't really take the credit for it, but it did make me feel a certain way.

I'm sure some are making a big deal out of the fact that you sing through 85 percent of this record, but to me, it's a completely natural evolution. I think of "Night People" from Ordinary Corrupt Human Love. Did you always like to sing? Which singers have stuck with you over the years?

A ton. I've listened to traditional singing—or whatever you want to call it—artists forever. Some of my favorite performers are non-metal performers.

But that said, no. It was nothing that I really pursued myself outside of the shower, you know what I mean? Outside of just fun on my own, like most people do, I never really pursued it.

I was in theater for four or five years, and I did musical theater during that time. But even that was mostly secondary. I preferred drama. I didn't do anything for a long time, and it was something we had discussed in the band and something I was pulling toward and experimented with on a couple of occasions on Ordinary.

Once we were given all this time and opportunity to write this album, I decided I wanted to take it more seriously and fully pursue the idea.

Deafheaven at the 2019 GRAMMY Awards. Photo: Jon Kopaloff/Getty Images

Hundreds of shows into your career, did you start to feel limited by screaming?

Not so much in its expression. I still feel like it is oftentimes the ultimate way for me to express an idea or emotion, to express that level of intensity. I still think, ultimately, it is a preference of mine. But in terms of technique, I was feeling limited. I just kind of felt like I had done all I could do with my range, stamina, rhythm and everything else.

Like you said, we tour quite often. I think we had done, in that year, five full tours. That definitely was a catalyst for those decisions as well, or it just reinforced those feelings. I wanted to be fully sure this was a decision I wanted to make before I did it.

I remember playing that show in January, and we had already been kind of working on songs and I had been thinking about the clean-vocal idea. After that January 2020 show, I knew that I definitely wanted to pursue it.

You mentioned in a podcast with [Touché Amoré's] Jeremy Bolm that you had started to be at odds with your position in the band. That you felt like the musical weak link in some way. Was that a motivation as well?

I think so. By the winter of 2019, we had had two songs and maybe the skeleton of a third. I knew at that point this wasn't going to work [with screaming]. We could have pursued it anyway, but I just wouldn't have been happy.

The guys often don't see that juxtaposition as wrong in any scenario. I think they're always comfortable with and wanting a harsh vocal on whatever kind of bed they end up creating. But for me, it was just the artistic aspect of it. I wanted to be challenged in that way.

When people say "Oh, he's singing now," it's so much more than just the tone. The writing is so different. It's not one-note rhythm writing, which is what aggressive vocals are. You're not moving a lot melodically. It's purely rhythm. For this, you need lot more. And if you want to make something creative and not just standard, you need to have dexterity in your vocal and a little bit of range and a lot of confidence.

"In terms of technique, I was feeling limited. I just kind of felt like I had done all I could do with my range, stamina, rhythm and everything else."

It was developing those things with JMJ [Justin Meldal-Johnsen] that, to me, really got it over the finish line. It's not just hitting the notes. It's your delivery. It's wanting to make choruses. And I've said this a lot, but I'll say it again: I've never written a chorus at all.

I've been listening to them my whole life, so it's like, "What eras do I want to link to mine? How am I feeling? Am I listening to a lot of '70s music, or '80s music, or '90s music? Where am I pulling from?" Essentially, I have a blank canvas here. I think that's what made it take as long as I did because I worked on them for over a year, continuously.

You could have easily gone off the rails with overly complex melodies, but the chorus to "Great Mass of Color" is three notes. It seems like you've stripped down your melodic vocabulary for maximum catchiness.

We did, yeah! Especially between me and Justin, there's a lot of those conversations. I was having to rework my lyrics in different ways and there was a little bit of strain. I didn't want to lose ideas, but I did want to filter them in a way that was simple enough to be effective. A chorus is kind of a universal thing. It doesn't need to be the highest brow. It just needs to be impactful and emotional.

But then you have "Villain," one of the first songs we worked on vocally, with all the falsetto things. That was more of a product of what you're saying. It's this big empty canvas where I could do whatever I want, so there are moments where there are jumps into less standard territory. I was hoping for a blend between the two.

You mentioned Chet Baker as an influence on your singing voice. I'm a Chet Baker lunatic.

That rules. A little bit! I was trying to find voices that had a sweet strength to them. When I was deciding on how I wanted my vocal approach to be, one of the things I was considering was shoegaze live and how it's very difficult to mix, especially in smaller clubs. From the top down, everyone has a little bit of struggle. I knew how the music was developing, so I needed a voice where I could compete with loud guitars but not always be full rock.

There are moments on the record where I accentuate more of this rocking voice, but what I described is sweet strength that has legs to it. I find that a lot with [Chet Baker]. I was listening to a lot of Nina Simone and Tears for Fears and stuff that has a dreamy bed of music but doesn't sacrifice the vocal to that sound. It has a very impactful voice on top of it to, in a way, compete.

It's a balancing act between insubstantial, wispy shoegaze vocals and, like, Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Yes, yes, yes, exactly. I dabbled in both. There are so many demos, in part, because I wanted to record everything to hear it back. And, yes, I was going both directions and was hoping to find a middle ground, and maybe I did. I don't know. It's why songs like "In Blur" or "The Gnashing" have a different tonal quality than "Other Language" or "Great Mass of Color."

Chet kind of tossed his voice, but not flimsily. He owned the high notes.

It's that control. That's exactly what I mean. It's less breathy, less careless. They're not supposed to be what shines in shoegaze; it's just another textural element. And we didn't want to be a shoegaze band. I think while this record has a lot of that in there, I wouldn't call it that. Our defining marker was that vocal decision.

Fans glom onto one lyric or another with each Deafheaven record, but I feel like your lyrics remain weirdly underdiscussed. What can you tell me about your lyrical approach for this one? What are you reading lately?

Thank you. I'm into these lyrics. They're a real patchwork of all these different themes, and no song is about any singular thing, necessarily. They have major motifs, but it's all [multifaceted]. The reason is that, originally, I wanted it to be kind of a concept record surrounding family—estranged family, and how those figures find their way into your life in this bigger connection.

But through the course of years, I was reflecting so much on all the heightened emotion of 2020 and the California fires that were happening and the protests and all these things. Those were finding their way into the lyrics, and I just kind of made a patchwork of both things. There's equal parts familial reflection and a present-day doomsday feeling.

I'm trying to think of what I was reading. I've been reading a lot of political stuff in the last year and a half. I felt my headspace was in that area. But, yeah, a lot of Polish stuff. I was reading Aleksander Wat, Szymborska, Milosz. I was reading a lot of Lydia Davis. I got that essay and short story anthology she put out. That's some of them.

You post your photography on Instagram, and I know you put out a couple of books of poetry. It seems like you're finding ways to express yourself beyond this thing you do 10 months a year.

Yeah, I'd like to do more of that. I am doing more of that. Maybe since I turned 30, I've been in this highly motivated zone, just really wanting to do things. Last year probably perpetuated it some, but I'm just looking to be busy. I love all those steps—conceptualizing and then seeing something through, whether it's writing or photography or music. It's all kind of thrilling. I think all that stuff is just in an effort to keep my brain occupied.

Or maybe just becoming a more balanced human being?

And learning! I'd never picked up a camera. I got a camera a few years ago and, through books and YouTube and whatever else, and texting friends that shoot film, I learned all this stuff. I develop and scan everything at my place. It's been cool to exercise that muscle more.

How did you get over the hump of "amateur photography"?

Oh, I'm amateur hour through and through. I'm an absolute hobbyist. Thankfully, a couple of friends have asked me to take their photo and it's great practice, but anything that looks professional or set-up is just [me] having some fun with it. I've taken so many and there's a lot of s**t. My goal is always to have a high average of what I call "keeps" from each roll, and I'm still on the low. [Laughs.]

What's going through your head as you prepare to head back on tour? Do you feel apprehensive about how this material will be received? That some fans might just want the screaming songs?

Honestly, I think our audience is going to be accepting. The show is going to have a lot more [dynamism] now with these new songs. Overall, the picture will be more interesting and varied.

But there's a ton of thought going into the technical aspect of it. We got together a couple of months ago to run the songs as we'll be doing them. Everyone has in-ear monitors now and we have a totally different amp setup with tons of different pedal and synth configurations now. There's a click track, which we've never done before. So, there's different bridges to cross.

If anything, that's where the nerves are coming from. But we have a lot of time and we are typically well-prepared people, so I feel really good. I feel mostly excited to play shows and see friends and see the country and hopefully see the world at some point soon and just get on with it.

And just play music without being a conversation piece?

If there's anything I want from people or from the record, it's just to take some time with it and to really listen to it. We put a lot of work into it. It's very detailed. When people receive the package, that aspect is very detailed as well.

And it doesn't really need to be more than that. It's just a record.

The above was drawn from two conversations and has been lightly edited for clarity.

Photo: Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

news

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

The Olympic Games have long featured iconic musical performances – and this year is no different. Check out the performers who took the stage in the City of Light during the 2024 Olympics Opening Ceremony in Paris.

The 2024 Paris Olympics came to life today as the Parade of Nations glided along the Seine River for the opening ceremony. The opening spectacular featured musical performances from Lady Gaga, Celine Dion, and more. Earlier in the week, some of music’s biggest names were also spotted in the city for the Olympics, including Olympics special correspondent Snoop Dogg, BTS' Jin, Pharrell Williams, Tyla, Rosalía, and Ariana Grande.

Read More: When The GRAMMYs & Olympics Align: 7 Times Music's Biggest Night Met Global Sports Glory

Below, see a full breakdown of some of the special musical moments from the 2024 Paris Olympics opening ceremony.

Lady Gaga

In a grand entrance, Lady Gaga emerged behind a heart-shaped plume of feathers on the golden steps of Square Barye, captivating the audience with her cover of the French classic "Mon truc en plumes." Accompanied by cabaret-style background dancers, she flawlessly belted out the song, executed impressive choreography, and even played the piano.

Lady Gaga’s connection to the song is notable, as Zizi Jeanmarie, the original artist, starred in Cole Porter’s musical "Anything Goes," which was Lady Gaga’s debut jazz release.

"Although I am not a French artist, I have always felt a very special connection with French people and singing French music — I wanted nothing more than to create a performance that would warm the heart of France, celebrate French art and music, and on such a momentous occasion remind everyone of one of the most magical cities on earth — Paris," Lady Gaga shared on Instagram.

Celine Dion

Closing out the ceremony with her first performance in four years since being diagnosed with stiff-person syndrome, Celine Dion delivered a stunning rendition of Edith Piaf’s everlasting classic, "L’Hymne à l’amour" from the Eiffel Tower. Her impressive vocals made it seem as though she had never left.

This performance marked Dion’s return to the Olympic stage; she previously performed "The Power of the Dream" with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and composer David Foster for the 1996 Olympics.

Axelle Saint-Cirel

Performing the National Anthem is no small feat, yet French mezzo-soprano Axelle Saint-Cirel knocked it out of the park.

Dressed in a French-flag-inspired Dior gown, she delivered a stunning rendition of "La Marseillaise" from the roof of the Grand Palais, infusing the patriotic anthem with her own contemporary twist.

With the stirring lyrics, "To arms, citizens! Form your battalions. Let’s march, let’s march," Saint-Cirel brought the spirit of patriotism resonated powerfully throughout the city.

Gojira

Making history as the first metal band to perform at the Olympics Opening Ceremony is just one way Gojira made their mark at the event.

The French band took the stage at the Conciergerie, a historic site that once housed French kings during medieval times and later became a prison during the French Revolution, famously detaining Marie Antoinette – Creating a monumental moment as the first metal band to perform at the ceremony, but also stirring the pot as they used the chance to nod toward politics.

Performing a revamped version of "Ah! Ça Ira," an anthem that grew popular during the French Revolution, the artists aren’t new to using their songs as a vehicle for political messages. The GRAMMY-nominated group are outspoken about issues concerning the environment, particularly with their song, "Amazonia," which called out the climate crisis in the Amazon Rainforest. Using music to spread awareness about political issues is about as metal as it gets.

Aya Nakamura

Currently France’s most-streamed musician, Aya Nakamura went for gold in a striking metallic outfit as she took the stage alongside members of the French Republican Guard. As there were showstopping, blazing fireworks going off behind her, she performed two of her own hit songs, "Pookie" and "Djadja," then followed with renditions of Charles Aznavour’s "For Me Formidable" and "La Bohème."

Although there was backlash regarding Nakamura’s suitability for performing at the ceremony, French President Emmanuel Macron dismissed the criticism. "She speaks to a good number of our fellow citizens and I think she is absolutely in her rightful place in an opening or closing ceremony," Macron told the Guardian.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

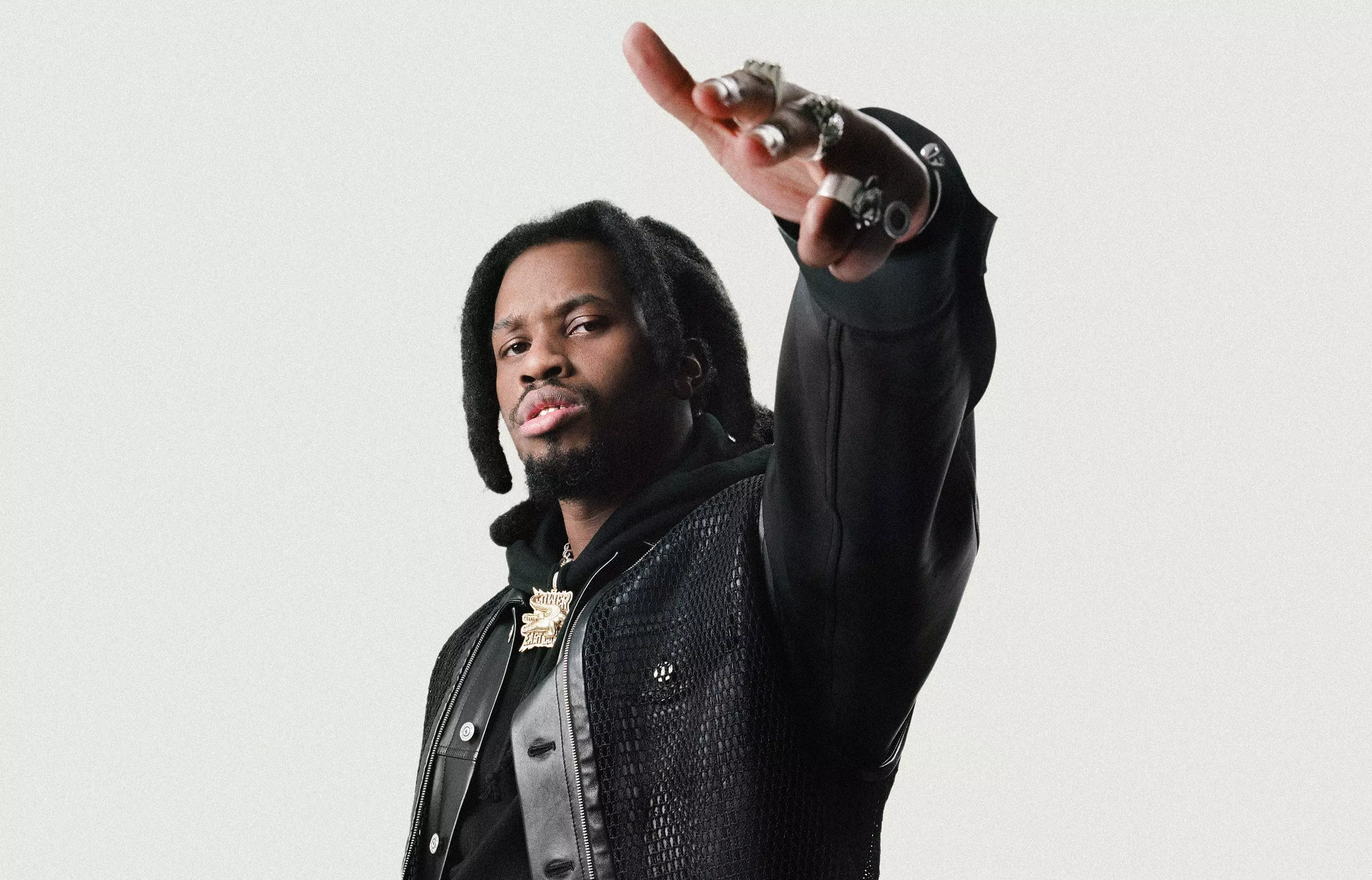

Photo: Matt Jelonek/Getty Images

list

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

The 10-track LP clocks in at just under 24 minutes, but it's packed with insanely quotable one-liners, star-studded collaborations, and bold statements.

Since Ice Spice first caught our attention two summers ago, she's been nothing short of a rap sensation. From viral hits like her breakout "Munch (Feelin' U)," to co-signs from Drake and Cardi B, to a Best New Artist nomination at the 2024 GRAMMYs, the Bronx native continues to build on her momentum — and now, she adds a debut album to her feats.

Poised to be one of the hottest drops of the summer, Y2K! expands on Ice Spice's nonchalant flow and showcases her versatility across 10 unabashedly fierce tracks. She dabbles in Jersey club on "Did It First," throws fiery lines on lead single "Think U the S— (Fart)," and follows the album's nostalgic title with an interpolation of an early '00s Sean Paul hit on "Gimmie a Light."

Y2K! also adds more star-studded features to Ice Spice's catalog, with Travis Scott, Gunna and Central Cee featuring on "Oh Shh...," "B— I'm Packin'," and "Did It First," respectively. At the helm is producer RiotUSA, Ice Spice's longtime friend-turned-collaborator who has had a hand in producing most of the rapper's music — proving that she's found her stride.

As you stream Ice Spice's new album, here are five key takeaways from her much-awaited debut, Y2K!.

She Doubles Down On Bronx Drill

Ice Spice is one of the few ladies holding down the New York drill scene on a mainstream level. She's particularly rooted in Bronx drill, a hip-hop subgenre known for its hard-hitting 808s, high-hats and synthesizers — and according to the sounds of Y2K!, it’s seemingly always going to be part of her artistry.

"It's always time to evolve and grow as an artist, so I'm not rushing to jump into another sound or rushing to do something different," Ice Spice told Apple Music of her tried-and-true musical style.

While Y2K! may not be as drill-driven as her debut EP Like…?, the album further hints that Ice isn't ready to retire the sound anytime soon. The subgenre is the dominant force across the album's 10 tracks, and most evident in "Did It First," "Gimmie a Light" and "BB Belt." Even so, she continues her knack for putting her own flair on drill, bringing elements of trap and electronic music into bops like "Oh Shhh…" and "Think U the S— (Fart)."

She Recruited Producers Old & New

Minus a few tunes, all of Ice Spice's songs start off with her signature "Stop playing with 'em, Riot" catchphrase — a direct nod to her right-hand man RiotUSA. Ice and Riot met while attending Purchase College in New York, and they've been making music together since 2021's "Bully Freestyle," which served as Ice's debut single. "As I was growing, she was growing, and we just kept it in-house and are growing together," Riot told Finals in a 2022 interview.

Riot produced every track on Like.. ? as well as "Barbie World," her GRAMMY-nominated Barbie soundtrack hit with Nicki Minaj. Their musical chemistry continues to shine on Y2K!, as Riot had a hand in each of the LP's 10 tracks.

In a surprising move, though, Ice doesn't just lean on Riot this time around. Synthetic, who worked on Lil Uzi Vert's GRAMMY-nominated "Just Wanna Rock," brings his Midas touch to "Think U the S—." Elsewhere, "B— I'm Packin'" is co-produced by Riot, Dj Heroin, and indie-pop duo Ojivolta, who earned a GRAMMY nomination in 2022 for their work on Kanye West's Donda. But even with others in the room, Riot's succinct-yet-boisterous beats paired with Ice's soft-spoken delivery once again prove to be the winning formula.

She Loves Her Y2K Culture

Named after Ice Spice's birthdate (January 1, 2000), her debut album celebrates all things Y2K, along with the music and colorful aesthetics that defined the exciting era. To drive home the album's throwback theme, Ice tapped iconic photographer David LaChapelle for the cover artwork, which features the emcee posing outside a graffiti-ridden subway station entrance. LaChapelle's vibrant, kitschy photoshoots of Mariah Carey, Lil' Kim, Britney Spears, and the Queen of Y2K Paris Hilton became synonymous with the turn of the millennium.

True to form, Y2K!'s penultimate song and second single "Gimmie a Light" borrows from Sean Paul's "Gimme the Light," which was virtually inescapable in 2002. "We really wanted to have a very authentic Y2K sample in there," Ice Spice said in a recent Apple Music Radio interview with Zane Lowe. Not only does the Sean Paul sample bring the nostalgia, but it displays Ice's willingness to adopt new sounds like dancehall on an otherwise drill-heavy LP.

Taking the Y2K vibes up another notch, album closer "TTYL," a reference to the acronym-based internet slang that ruled the AIM and texting culture of the early aughts. The song itself offers fans a peek insideIce's lavish and exhilarating lifestyle: "Five stars when I'm lunchin'/ Bad b—, so he munchin'/ Shoot a movie at Dunkin'/ I'm a brand, it's nothin.'"

She's A Certified Baddie

Whether she's flaunting her sex appeal in "B— I'm Packin'" or demanding potential suitors to sign NDAs in "Plenty Sun," Ice exudes confidence from start to finish on Y2K!.

On the fiery standout track "Popa," Ice demonstrates she's in a league of her own: "They ain't want me to win, I was chosen/ That b— talkin' s—, she get poked in/ Tell her drop her pin, we ain't bowlin'/ Make them b—hes sick, I got motion." And just a few songs later, she fully declares it with "BB Belt": "Everybody be knowin' my name (Like)/ Just want the money, I don't want the fame (Like)/ And I'm different, they ain't in my lane."

For Ice, "baddie" status goes beyond one's physical attributes; it's a mindset she sells with her sassy delivery and IDGAF attitude.

She's Deep In Her Bag

In album opener "Phat Butt," Ice boasts about rocking Dolce & Gabbana, popping champagne, and being a four-time GRAMMY nominee: "Never lucky, I been blessed/ Queen said I'm the princess/ Been gettin' them big checks in a big house/ Havin' rich sex," she asserts.

Further down the track list, Ice Spice firmly stands in her place as rap's newest queen. In "BB Belt," she raps, "I get money, b—, I am a millionaire/ Walk in the party, everybody gon' stare/ If I ain't the one, why the f— am I here, hm?"

Between trekking across the globe for her first headlining tour and lighting up the Empire State Building orange as part of her Y2K! album rollout, Ice Spice shows no signs of slowing down. And as "BB Belt" alludes, her deal with 10K Projects/Capitol Records (she owns her masters and publishing) is further proof that she's the one calling the shots in her career.

Whatever Ice decides to do next, Y2K! stands as a victory lap; it shows her prowess as drill's latest superstar, but also proves she has the confidence to tackle new sounds. As she rapped in 2023's "Bikini Bottom," "How can I lose if I'm already chose?" Judging by her debut album, Ice Spice is determined to keep living that mantra.

More Rap News

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

On Rakim's 'G.O.D's Network (REB7RTH)' The MC Turned Producer Continues His Legacy With An All-Star Cast

5 Ways Mac Dre's Final Living Albums Shaped Bay Area Rap

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

Photo: Brett Carlsen/Getty Images for Spotify

news

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

As July comes to a close, there's another slew of new musical gems to indulge. Check out the latest albums and songs from Paris Hilton and Meghan Trainor, Mustard and more that dropped on July 26.

July has graced us with a diverse array of new music from all genres, lighting up dance floors and speakers everywhere.

The last weekend of the month brings exciting new collaborations, including another iconic track from Calvin Harris and Ellie Goulding, as well as a fierce team-up from Paris Hilton and Meghan Trainor. Halsey and Muni Long offered a taste of their forthcoming projects, while Jordan Davis and Miranda Lambert each delivered fun new country tunes.

In addition to fresh collabs and singles, there's a treasure trove of new albums to uncover. Highlights include Ice Spice's Y2K!, Rakim's G.O.D., Sam Tompkins' hi, my name is insecure, Wild Rivers' Never Better, Tigirlily Gold's Blonde, and kenzie's biting my tongue.

As you check out all the new music that dropped today, be sure you don't miss these 10 tracks and albums.

mgk & Jelly Roll — "Lonely Road"

Although fans anticipated Machine Gun Kelly's next release to mark his return to hip-hop, no one seems to be complaining about "KellyRoll." Embracing the trend of venturing into the country genre, mgk teams up with fellow GRAMMY-nominated artist Jelly Roll on their newest track, "Lonely Road."

The genre-blending track interpolates John Denver's classic "Take Me Home, Country Roads." However, unlike Denver's sentimental ode to the simplicity of rural life, mgk and Jelly Roll reinterpret the track through the lens of romantic relationships that have come to a, well, lonely end.

As mgk revealed in an Instagram post, "Lonely Road" was a labor of love for both him and Jelly Roll. "We worked on 'Lonely Road' for 2 years, 8 different studios, 4 different countries, changed the key 4 times," he wrote. "We finally got it right."

Halsey — "Lucky"

In another interpolation special, Halsey samples not one but two classics in their latest single, "Lucky." The song's production features elements of Monica's 1999 hit "Angel of Mine," while the chorus flips Britney Spears' fan-favorite "Lucky" into a first-person narrative.

While Halsey has always been a transparent star, their next project is seemingly going to be even more honest than their previous releases. After first revealing their journey with lupus with the super-personal "The End" in June, "Lucky" further details their struggles: "And I told everybody I was fine for a whole damn year/ And that's the biggest lie of my career."

Though they haven't revealed a release date for their next project, Halsey referred to her next era as a "monumental moment in my life" in an Instagram post about the "Lucky" music video — hinting that it may just be their most powerful project yet.

Read More: Everything We Know About Halsey's New Album

Paris Hilton & Meghan Trainor — "Chasin'"

Ahead of Paris Hilton's forthcoming album, Infinite Icon — her first in nearly 20 years — the multihyphenate unveiled another female-powered collaboration, this time with Meghan Trainor. Co-produced by Sia, "Chasin'" is a lively pop anthem about discovering self-worth in romantic relationships and finding the strength to walk away from toxicity.

"She is the sister I always needed and when she calls me sis, I die of happiness inside," Trainor told Rolling Stone about her relationship with Hilton. Coincidentally, Trainor first wrote the track with her brother, Ryan, but the pop star was waiting for the right collaborator to hop on the track — and Hilton was just that.

"We made something truly iconic together," Trainor added. "It was a bucket list dream come true for me."

Empire Of The Sun — 'Ask That God'

A highly awaited return to music after eight years, Australian electro-pop duo Empire Of The Sun are back with their fourth studio album, Ask That God.

"This body of work represents the greatest shift in consciousness our world has ever seen and that's reflected in the music," says member Lord Littlemore in a press statement.

Like their previous work that transports listeners to a different universe, this album continues that tradition with trancey tracks like lead single "Changes" and the thumping title track. Ask That God offers a chance to reflect on the blend of reality and imagination, while also evoking the radiant energy of their past songs.

Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding — "Free"

Dance music's collaborative powerhouse, Calvin Harris and Ellie Goulding, are back with another summer hit. Their latest track, "Free," marks the fourth collaboration between the duo — and like their past trilogy of hits, the two have another banger on their hands.

The track debuted earlier this month at Harris' show in Ibiza, where Goulding made a surprise appearance to perform "Free" live. With Harris delivering an infectious uptempo house beat and Goulding's silky vocals elevating the track, "Free" proves that the pair still have plenty of musical chemistry left.

Post Malone & Luke Combs — "Guy For That"

Post Malone's transition into country music has been anything but slow; in fact, the artist went full-throttle into the genre. The New York-born, Texas-raised star embraced his new country era with collaborations alongside some of the genre's biggest superstars, like Morgan Wallen and Blake Shelton. Continuing this momentum as he gets closer to releasing F-1 Trillion, Post Malone teams up with Luke Combs for the new track "Guy For That."

The catchy collaboration tells the story of a relationship that has faded, where the protagonist knows someone who can fix almost anything, except for a broken heart. It's an upbeat breakup song that, like Post's previous F-1 Trillion releases, can get any party going — especially one in Nashville, as Malone and Combs did in the track's music video.

Forrest Frank & Tori Kelly — "Miracle Worker"

Just one month after Surfaces released their latest album, good morning, the duo's Forrest Frank unveiled his own project, CHILD OF GOD — his debut full-length Christian album. Among several features on the LP, one of the standouts is with GRAMMY-winning artist Tori Kelly on the track "Miracle Worker."

Over a plucky electric guitar and lo-fi beats, Frank and Kelly trade verses before joining for the second chorus. Their impassioned vocals elevate the song's hopeful prayer, "Miracle Worker make me new."

Their collaboration arrives just before both artists hit the road for their respective tours. Frank kicks his U.S. trek off in Charlotte, North Carolina on July 31, and Kelly starts her world tour in Taipei, Taiwan on Aug. 17.

XG — "SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT"

Since their debut in 2022 with "Tippy Toes," Japanese girl group XG has been making waves and showing no signs of slowing down. With their first mini album released in 2023 and now their latest single, "SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT," the group continues to rise with their distinctive visuals and infectious hits.

The track features a nostalgic rhythm reminiscent of early 90s R&B, showcasing the unique personalities of each member. As an uptempo dance track, it's designed to resonate with listeners from all across the globe.

"SOMETHING AIN'T RIGHT" also serves as the lead single for XG's upcoming second mini album, set to release later this year.

Mustard — 'Faith of a Mustard Seed'

For nearly 15 years, Mustard has been a go-to producer for some of rap's biggest names, from Gucci Mane to Travis Scott. On the heels of earning his first Billboard Hot 100 chart-topper as a producer with Kendrick Lamar's "Not Like Us," he's back with his own collaboration-filled project.

Faith of a Mustard Seed features a robust 14-song track list with contributions from Vince Staples, Lil Yachty, Charlie Wilson, and more. The LP marks Mustard's fourth studio album, and first since 2019's Perfect Ten.

In an interview with Billboard, Mustard shared that the album's title is an ode to late rapper Nipsey Hussle, who suggested the title during one of their final conversations before his untimely death in 2019. And once "Not Like Us" hit No. 1, Mustard knew it was time to release the long-in-the-making album.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'