Photo: Theo Wargo/WireImage for Consilium Ventures

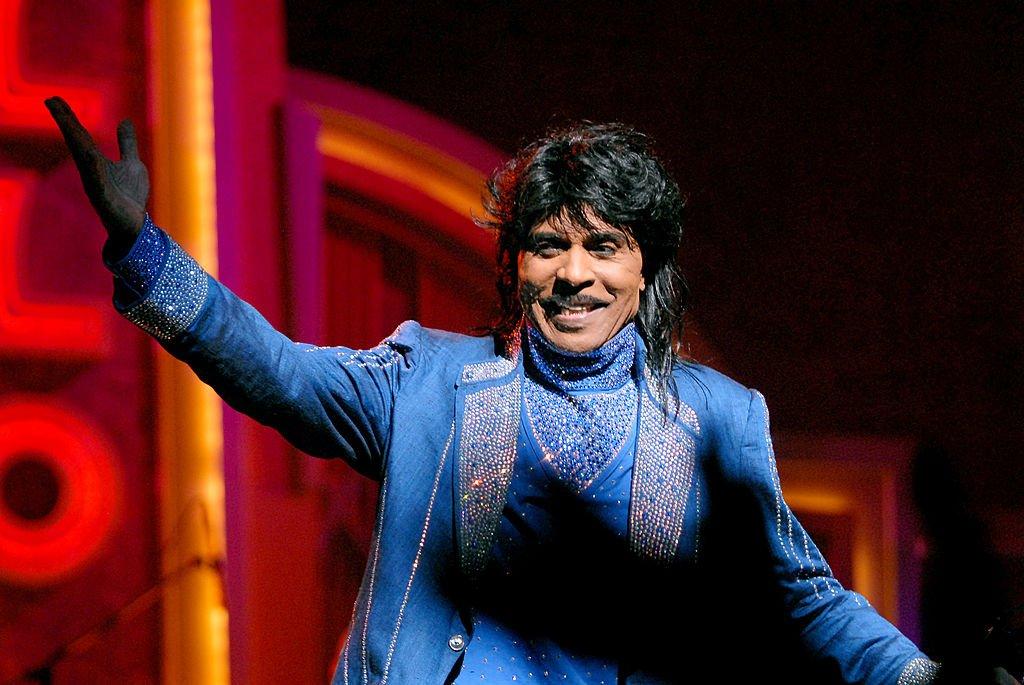

Little Richard performs at the Apollo Theatre in 2006

news

Little Richard Was The Lightning Storm That Awakened Rock

The screamer-songwriter was like nothing America had ever seen, and his unbridled joy made rock 'n' roll come alive

In your mind's eye, picture a few rock superstars: Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, Tina Turner, Elton John, AC/DC, Prince. Chances are you thought about one of them in the past week. Now picture none of them picking up an instrument, none of them writing a tune, none of them entering your life. If Little Richard hadn't been born in 1932, this would arguably be the world we live in—a passable, but perhaps joyless place.

Little Richard didn't just play the piano passionately, or sing about joyful subjects. He was like an alien dispatched from Andromeda to administer humanity a joy inoculation. Imagine 1950s America getting an eyeful of him: his circus-freak pompadour, his gender- and race-ambiguous makeup, his flash of sequins. Just as exotic was the tortured glossolalia he screamed as if he was on fire: "A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom!" from 1955's "Tutti Frutti." But as the first chapter of nearly every rock biography will attest, pent-up girls and boys all around the war-torn world read him loud and clear.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//NnIIvWnpaBU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The artist born Richard Wayne Penniman, who died Saturday (May 9) at 87, wasn't the King Of Rock 'N' Roll (that's Elvis Presley), and he wasn't its founding father either (that's Chuck Berry). Watch the 1931 film Frankenstein: If rock music is Promethean Man in the watchtower lab, then Little Richard is the electrical storm that animates him, and the terrified populace is ... well, the terrified populace. But while a mob eventually cornered Frankenstein's monster in a windmill and set it ablaze, Little Richard's impact was, and still is, uncontainable.

Soon after Little Richard dropped "Long Tall Sally" in 1956, Paul McCartney decided it'd be the first song he sang in public. When asked to describe his life's aspiration in his high school yearbook, Bob Dylan wrote: "To join Little Richard." A pre-Ziggy Stardust Bowie took notes on his hairdo, among other things. Hendrix would join his band in a decade and form The Experience a year after he left. Tina Turner based her early vocal delivery on Little Richard's. Elton John heard him and closed the menu of life choices: "I didn't ever want to be anything else." AC/DC singer Brian Johnson once described him in Genesis 1:1 terms: "There was nothing, and then there was this." As for Prince, the "gestures vaguely at everything" meme will have to do. Little Richard was a bell nobody could unring, and his chime still resonates unceasingly.

Even among his fellow rock 'n' roll pioneers, Little Richard was something strange and different. While Presley was a humble country boy and Berry was a poet with a guitar, Little Richard was a living remix of Baptist and Pentecostal church and the minstrel shows, traveling circuses and drag revues on which he cut his teeth. Beginning when he was 18, he had a few false starts in the studio: Incensed by his flamboyance and perceived impudence, Peacock Records owner Don Robey beat Little Richard so badly, he required surgery. Undeterred, Little Richard sent Specialty Records a demo two years later; producer Robert "Bumps" Blackwell described the tape as "looking as though someone had eaten off it." After Little Richard repeatedly called their staff begging them to listen to it, they relented and set up a recording date at J & M Studio in New Orleans.

Still, the recording session wasn't working; Little Richard was frustrated that his sound wasn't catching fire. He remembered "Tutti Frutti," a naughty song he had absentmindedly written while working as a dishwasher at a Greyhound station. He cleaned up the song's sexual references, and after a lunch break, he let it rip with that nonsensical, unforgettable refrain. The exuberant resulting single, which was a watershed for black vernacular in a pop song, hit No. 2 on the Billboard Rhythm and Blues Chart and was added to the Library Of Congress National Recording Registry in 2010. In 1998, "Tutti Frutti" was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall Of Fame.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//XkkrTuuG0X8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"I wrote 'Tutti Frutti' in the kitchen, I wrote 'Good Golly Miss Molly' in the kitchen, I wrote 'Long Tall Sally' in that kitchen," Little Richard later explained to Rolling Stone in 1970 about the bus stop gig; he followed up "'Tutti Frutti" with those just-as-exultant barnburners. The cover of his 1957 debut album, Here's Little Richard, featuring a close-up of Richard in mid-scream that would make Edvard Munch proud, is the ultimate truth in advertising: There's zero ambiguity about what the music inside will sound like.

And that sound was unbridled liberation—from whitewashed suburbia, from hellfire religion typified by the preacher in 1978's The Buddy Holly Story, from the anodyne pop on the airwaves. (The Billboard pop chart in 1954 was full of downtempo tracks by Rosemary Clooney, Kitty Kallen and The Crew-Cuts.) After Little Richard experienced a religious conversation and left secular music in 1962, coming back to a music scene dominated by the British boys who idolized him, like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, was no easy task. After flower power and Woodstock made his provocations seem quaint, he soon became a thing of the rock 'n' roll revival circuit.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//E68N5E1d0_M' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

A zip code away from his macho peers, Little Richard was a rock star that LGBTQ folks could look up to before coming out was the norm, and he galvanized Bowie and Prince to tear up the rulebook of gender expression. And his unspoken message, whether to those in a bind over their sexuality or not, was abundantly clear: No matter who you are, scream it out. That scream was one-size-fits-all for the human experience. When you hear Macca howling like a maniac on "I'm Down," "Hey Jude" and "Oh! Darling," understand that The Beatles' keyhole to jubilation—and therefore, everyone's—had a Little-Richard-shaped key.

The songs Little Richard co-wrote or interpreted all have the same feeling of anticipation, which is applicable to every stage of life: the last minutes of school on a Friday, the beginning of an unforgettable night out, the first blush of romantic attraction. He's ready to cause trouble, but the good-natured kind—the kind that doesn't put anybody down, but instead drags everyone off the couch and into a raucous block party. His songs exist at the perpetual "here we go" moment, the exhilarating flash on the rollercoaster when your stomach plunges.

We're gonna have some fun tonight. Everything's all right.

Photo: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

list

8 Ways Sade's 'Diamond Life' Album Redefined '80s Music & Influenced Culture

As Sade's masterpiece 'Diamond Life' turns 40, see how the group's debut pushed R&B forward and introduced them as beloved elusive stars.

"I only make records when I feel I have something to say," Sade Adu asserted in 2010 upon the highly anticipated release of Sade's GRAMMY-winning Soldier of Love album, which arrived after a 10-year hiatus. "I'm not interested in releasing music just for the sake of selling something. Sade is not a brand."

This lifetime of dedication toward achieving musical excellence helped Sade — vocalist Adu, bassist Paul S. Denman, keyboardist Andrew Hale, and guitarist/saxophonist Stuart Matthewman — gain prominence in the mid-80s, also garnering enormous respect from fans, critics, and peers alike. Formed in 1982, the English band is one of the few acts that can still be met with a hungry audience after disappearing from the spotlight for multiple years.

In an industry where churning out a new body of work is expected every couple of years, the four meticulous members of Sade move on their own time, putting out a mere six studio albums since 1984. Every project becomes more exquisite than the last, but it all began 40 years ago with Sade's illustrious debut album, Diamond Life. Ubiquitous hits like "Smooth Operator" and "Your Love Is King" appealed to listeners young and old — offering a unique blend of R&B, jazz, soul, funk, and pop that birthed a new sound and forced the industry to take notes from the jump.

As Sade's Diamond Life celebrates a milestone anniversary, here's a look at how the album helped push R&B forward, and why it's just as relevant today.

It Helped Set Off The "Quiet Storm" Craze

By mid-1984, Michael Jackson, was riding high off of winning the most GRAMMYs in a single night (including Album Of The Year) for his blockbuster album Thriller, Madonna celebrated her first top 10 hit with "Borderline," and Prince's Purple Rain was just days away from its theatrical release. Duran Duran, Culture Club, Billy Idol, and the Police were mainstays, while "blue-eyed soul" in particular had also hit an all-time high thanks to Hall and Oates, Wham, Simply Red, and others. What's more, many Black artists like Lionel Richie and Whitney Houston opted for more of a pop sound to appeal to broader audiences during MTV's golden era.

Diamond Life was refreshing at the time, as it fully embraced soul and R&B. The album offered a chic sophistication amid the synth-heavy pop and rock music that ruled the charts.

Singles like "Your Love Is King" and "Smooth Operator" introduced jazz elements into mainstream radio. In turn, Sade helped usher in the "quiet storm" genre — R&B music at its core, with strong undertones of jazz for an ultra-smooth sound. Sade and Diamond Life also laid some of the groundwork for neo-soul, which saw a surge in the '90s à la Lauryn Hill, Maxwell, and Erykah Badu.

It Made GRAMMY History

In the 65-year history of the GRAMMYs, a small number of Nigerian artists, including Burna Boy and Tems, have won a golden gramophone. In 1986, a then 27-year-old Sade Adu made history as the first-ever Nigerian-born artist to win a GRAMMY when she and her band was crowned Best New Artist at the 29th GRAMMYs. Still, Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg had to accept the award on Sade's behalf — signaling Adu's elusive nature as she rarely attends industry events or grants interviews.

Since then, Sade has gone on to earn three more GRAMMYs, including Best Pop Vocal Album in 2001 for their fifth studio album, Lovers Rock. The win signified their staying power in the new millennium.

It Birthed The Band's Signature Song…

While Diamond Life spawned timeless hits like "Your Love Is King" and "Hang On to Your Love," "Smooth Operator" became the album's highest-charting single — and remains the most iconic song in their catalog. The seductive track about a cunning two-timer propelled the band into international stardom: "Smooth Operator" skyrocketed to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 and hit No. 1 on the Adult Contemporary chart.

Even non-Sade fans can identify "Smooth Operator" in an instant, from Adu's unmistakable vocals to that now-iconic instrumental saxophone solo. As of press time, it boasts over 400 million Spotify streams alone, and has remained a set list staple across every one of Sade's tours.

…And It Houses Underrated Gems

"Smooth Operator" may be Sade's commercial classic, but deep cuts like "Frankie's First Affair," "Cherry Pie," and "I Will Be Your Friend" are fan favorites that embody the band's heart and soul.

"Frankie's First Affair" offers a surprisingly enchanting take on infidelity: "Frankie, didn't I tell you, you've got the world in the palm of your hand/ Frankie, didn't I tell you they're running at your command." And, it's impossible to resist the funky groove that carries standout track "Cherry Pie," which served as a catalyst for some of Sade's later, more dance-oriented hits, including "Never As Good As the First Time" and "Paradise." Some of Sade's most poignant statements about lost love, including "Somebody Already Broke My Heart" from 2000's Lovers Rock, can be traced back to "Cherry Pie."

Diamond Life's penultimate song, "I Will Be Your Friend," offers both solace and companionship — another recurring theme throughout Sade's music, from 1988's "Keep Looking" to 2010's "In Another Time."

It Was The Best-Selling Debut Album By A British Female Singer For More Than Two Decades

Sade has sold tens of millions of albums worldwide, but Diamond Life remains the band's most commercially successful LP with over 7 million copies sold. Most of Sade's other platinum-selling LPs, including Diamond Life's follow-up, 1985's Promise, boast sales between four and six million copies.

The 7 million feat helped Sade set the record for best-selling debut album by a British female singer. She held the title for nearly 25 years until Leona Lewis' 2008 album Spirit, which has sold over 8 million copies globally.

It Introduced Sade Adu As A Style Icon

When we first met Adu, her signature aesthetic consisted of a long, slicked-back ponytail, red lip, and gold hoops. Sade's impeccable style is front and center in early videos like "When Am I Going to Make a Living," in which she sports an all-white ensemble paired with a pale gray, ankle-length trench coat and loafers.

Adu rocked the model off-duty style long before it became a trend. Her oversized blazers, classic trousers, and head-to-toe denim looks were as effortless as they were chic and runway-ready — proving that less was more amid the decade of excess.

"It's now so acceptable to be wacky and have hair that goes in 101 directions and has several colours, and trendy, wacky clothes have become so acceptable that they're… conventional," Adu, who briefly worked as a fashion designer and model before pursuing music, told Rolling Stone in 1985. "I don't like looking outrageous. I don't want to look like everybody else."

It Shined A Light On Larger Societal Issues

While most of Diamond Life leans into love's ebbs and flows, a handful of tunes deal with financial strife coupled with a dose of optimism, as evidenced by "When Am I Going to Make a Living" and "Sally." The latter song characterizes the Salvation Army as a young charitable woman: "So put your hands together for Sally/ She's the one who cared for him/ Put your hands together for Sally/ She was there when his luck was running thin."

Meanwhile, Adu, a then-starving artist, scribbled down portions of "When Am I Going to Make a Living" on the back of her cleaning ticket. The soul-stirring "We are hungry, but we won't give in" refrain emerges as a powerful mantra in the face of adversity and still holds relevance in 2024. Similar themes appear throughout Sade's later work, including unemployment ("Feel No Pain"), unwanted pregnancy ("Tar Baby"), survival ("Jezebel"), prejudice ("Immigrant"), and injustice ("Slave Song").

Diamond Life closer "Why Can't We Live Together" is a well-done cover of Timmy Thomas' 1972 hit about the staggering Vietnam War deaths. The band wisely doesn't veer too far from the original recording, but Adu's distinctive contralto voice brings a haunting quality that's reminiscent of Billie Holiday.

It Ignited The Public's Ongoing Fascination With Sade Adu

Since 1984, Sade has only released six studio albums, and a remarkable 14 years have passed since the group's last offering, 2010's Soldier of Love. Ironically, that scarcity — both in terms of music and access to the artist — has actually added to Adu's appeal. Case in point: Sade's sold-out Soldier of Love Tour grossed over $50 million in 2011, and the band still brings in close to 14 million monthly listeners on Spotify.

Adu's striking beauty, mysterious persona, and knack for letting her music do all the talking has earned the admiration of her peers across genres and generations. Everyone from Beyoncé to Kanye West to Snoop Dogg have sung her praises. Drake even has two portrait-style tattoos of the singer on his torso. Prince reportedly described 1988's "Love Is Stronger Than Pride" as "one of the most beautiful songs ever." Metalheads Chino Moreno of the Deftones and Greg Puciato of the Dillinger Escape Plan have also cited Adu as inspiration — showing that her influence runs far and wide.

In 2022, reports circulated that Sade was recording new music at Miraval Studios in France. But upon Diamond Life's 40th anniversary, "Flower of the Universe" and "The Big Unknown" from the respective soundtracks to 2018 films A Wrinkle in Time and Widows stand as Sade's latest releases.

Whether fans get new music anytime soon remains to be seen, but the impressive repertoire of Adu, Denman, Hale, and Matthewman is one that aims to be truth-seeking and inspiring while exploring life's peaks and valleys. Diamond Life in particular holds up as one of the purest representations of the group's creative legacy, both commercially and musically.

From quadruple platinum status to resonating with several generations, Diamond Life will forever stand as a remarkable debut — one that continues to influence music in a multitude of ways.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Photo: Michael Crabtree - PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images

list

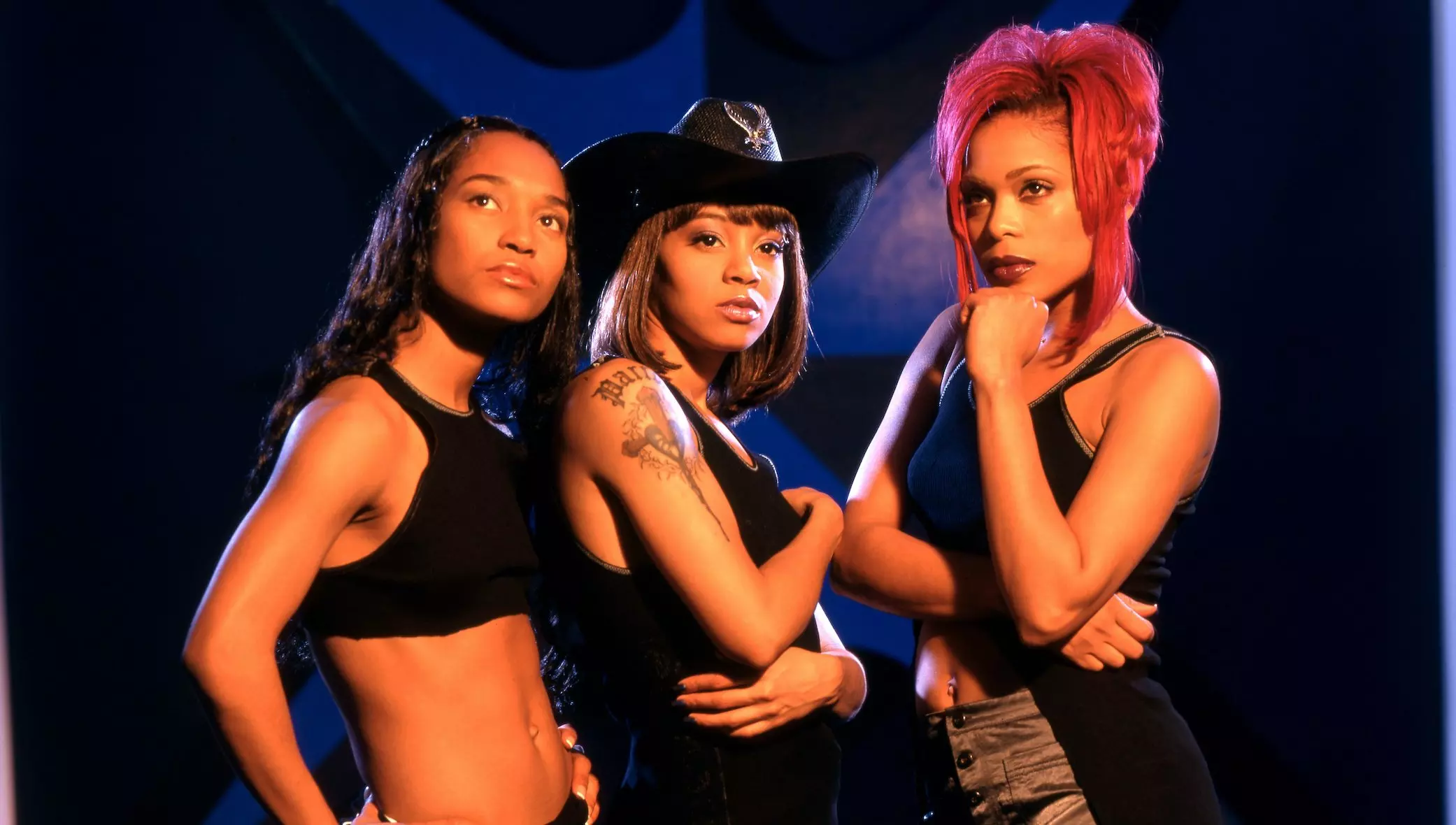

5 Reasons Why 'The Writing's On The Wall' Is Destiny's Child's Defining Album

From its embrace of experimental R&B production and memorable music videos, to its GRAMMY-winning empowering songs, 'The Writing’s On the Wall' remains a touchstone for fans of Destiny's Child.

In 1997, all-female R&B groups were thriving: TLC already had seven Top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100, En Vogue had numerous platinum singles, and Xscape reached No. 1 more than once. Soon, a quartet of teenagers would burst upon the scene and leave an indelible impact.

While Destiny’s Child are now canonical in the world of '90s and early aughts R&B, the group initially experienced spotty success. Their 1997 debut single, "No, No, No (Part 2)" peaked at No. 3 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and was certified platinum. Yet their eponymous album, released in February 1998, only hit No. 67. Their follow up single, "With Me," also failed to set the charts ablaze.

Destiny’s Child's underwhelming chart performances could’ve easily derailed the budding group. Fortunately, the four ambitious girls from Texas had other plans.

Beyoncé Knowles, Kelly Rowland, LaTavia Roberson, and Le Toya Luckett were determined not to become one hit wonders, and quickly went back into the studio to record their sophomore album. Released on July 14, 1999, The Writing’s On the Wall became Destiny’s Child’s highest selling album and spawned some of their most iconic songs — one of which led to the group's first GRAMMY win. Not only did the album establish Destiny's Child as a household name, but it fine tuned the R&B girl group concept to perfection.

"We had no idea that The Writing's on the Wall would be as big a record as it was. Especially worldwide," Beyoncé said in a 2006 Guardian interview.

In celebration of the iconic album's 25th anniversary, read on for five reasons why The Writing’s On the Wall is the defining album of Destiny’s Child’s career.

Its Members Took Creative Control

On their debut album, Destiny’s Child tapped into the neo soul trend popularized by the likes of D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, and Maxwell — artists in their early-to-mid twenties with a maturity the teen quartet didn’t yet have. The references and creative direction clashed with the reality of the group members being so young.

"It was a neo-soul record and we were 15 years old. It was way too mature for us," Beyoncé tol the Guardian.

Heading back into the studio, the girls made sure to eradicate any misalignments and put more of themselves into their sophomore album. In an interview with MTV, the members said The Writing’s On the Wall had a fresher, more youthful vibe because "it comes from us." The quartet's fingerprints are all over the 16 track album: Each member co-wrote at least 50 percent of the album.

"Even at the time, Beyoncé would produce a lot of their background vocals, and she was a leader even at a young age," Xscape's Kandi Burruss said in a Vice interview, reflecting on her work as a songwriter and producer on The Writing's On the Wall. This heightened presence enabled the group to develop lyrics that boldly reflected their opinions and youthful energy. In turn, The Writing's On the Wall netted a run of iconic hit singles.

Read more: Destiny's Child's Debut Album At 25: How A Neo-Soul Album From Teens Spawned R&B Legends

It Pushed R&B Forward

Like its predecessor, The Writing’s On the Wall is very much an R&B album. However, Beyoncé's father Mathew Knowles — who still managed the group at the time — brought in producers who weren’t afraid to experiment. The result was a more commercial album that fused classic R&B with pop influences, creating a sound that was simultaneously contemporary and timeless.

Kevin "She'kspere" Briggs and Burrus (who would go on to co-write and produce TLC’s "No Scrubs") contributed to five of the album's tracks, shaping its overall sound and differentiating it from Destiny’s Child. The duo kept a few elements from the group’s debut effort, including the sing-rapping heard on "Bug A Boo" and "Hey Ladies." With syncopated beats, thumping basslines, and their knack for writing catchy hooks, Briggs and Burrus created R&B records with the perfect blend of chart-friendly accessibility.

On the Missy Elliott produced "Confessions," synthesizers, drum machines, and electronic garbling were layered to create a lush, futuristic backdrop. Further subverting the classic R&B ballad, Elliott paired what sounds like a cabasa to match Beyonce’s cadence throughout the verses which gives her laidback vocals an almost robotic feel. In addition to producing, Elliott’s velvety vocals also appear quite prominently on the chorus, adding to the track’s sonic tapestry.

GRAMMY-winner Rodney Jerkins was tapped to produce "Say My Name." The original beat Jerkins used was two-step garage, a subgenre of UK garage. No one else liked the sound, so he completely revamped the track into the GRAMMY-winning anthem we know today. Jerkins melded funk-inspired guitar and a call and response approach, then modernized them with a shimmery, polished production. This helped "Say My Name" become the group’s most listened to song on Spotify with over 840 million streams. Jerkins has even gone on record to say this is his favorite song he’s produced to date.

Read more: "Say My Name" 20 Years Later: Why The Destiny's Child Staple Is Still On Everyone's Lips

Its Music Videos Praised Black Culture

"For me, it is about amplifying the beauty in all of us," Beyoncé said in a 2019 interview with Elle when asked about the importance of representation. Even before her solo work, the importance of spotlighting Black culture was evident in Destiny's Child's music videos.

In "Bills, Bills, Bills," we see the group play the role of hair stylists in a salon which is an obvious nod to Beyoncé's mother’s longstanding relationship with all things hair. Near the end of "Bug a Boo," the members change into their version of majorette costumes and dance in front of a marching band. Majorettes and marching bands have a vibrant legacy within HBCUs; almost 20 years after this video premiered, Beyoncé revisited this very concept for her 2018 Coachella performance.

It Delivered Mainstream Success

The Writing’s On the Wall was a hit across the charts. The group earned their first No. 1 singles on Billboard’s Hot 100 with "Bills, Bills, Bills" and "Say My Name." Promotions for the latter also reinvigorated album sales and helped shift another 157,000 copies (an impressive 15 percent increase from their first-week sales). The fourth and final single, "Jumpin’, Jumpin’" was released during the summer of 2000 and became one of the most played songs on the radio that year.

Songs from the album were nominated at both the 42nd and 43rd GRAMMY Awards. Destiny’s Child took home their first golden gramophone at the 2001 GRAMMYs, winning Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals for "Say My Name." The single also won Best R&B Song and was nominated for Record Of The Year.

With 14 nominations, Destiny’s Child remain the most nominated girl group in GRAMMY history. With worldwide sales of 13 million, The Writing’s On the Wall is also the fourth best-selling girl group album of all time.

It Expanded The Concept Of "Girl Power"

The Writing’s On the Wall was much more than catchy, radio-friendly tunes. Lyrically and in production, the album reintroduced Destiny’s Child as the architects for their own lives. The tongue-in-cheek Godfather-inspired intro tees up each song with a commandment for their partners and, at times, for themselves.

Often misconstrued as a gold digger anthem,"Bills, Bills, Bills" empowers a woman to confront a lover who's financially taking advantage of her. This is a far cry from the theme of a young woman focused on finding love — a common theme on Destiny's Child — and puts their confidence on full display. "So Good" is a sassy, uplifting anthem which explicitly addresses haters with pointed lyrics like "For all the people ‘round us that have been negative/Look at us now/See how we live." Destiny's Child was sending a clear message: they’re going to be fine regardless of what others say.

And when the group became tabloid fodder due to unexpected lineup changes, "So Good" took on a new meaning for persevering through hard times. While there are some songs with morally questionable lyrics — we’re looking at you ‘"Confessions" — the consistent message of embracing one’s self-worth and independence is clear.

More Girl Group Sounds & History

Photo: Robby Klein

interview

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

On his third album, the self-described "black sheep" of country music proves he's here to stay.

Haters take note: nothing fires up a country boy like HARDY more than a naysayer. And this redneck has a long memory.

Despite the coveted catalog of country music hits to his credit — tunes he wrote for artists like Florida Georgia Line, Blake Shelton and Morgan Wallen, plus his own work as a solo artist — HARDY's third album begins with a three-minute response to a heckler who once left a nasty note in his jar in place of a tip.

That moment may have occurred a decade ago, but it's key to HARDY's defiant persona. In fact, the album's title is exactly what that note read — Quit!! — and its cover art is the actual napkin the message was written on, which the singer/songwriter has held on to all these years.

HARDY laughs off the memory at first, but as the title track plays on, his olive branch soon turns to coal. "I'm not the GOAT, I'm the black sheep hell-bent to find closure," he barks as the song escalates. "I can't let go — a note somebody wrote like ten years ago put a chip on my shoulder. If you wanted me to quit, you should've saved it, bro."

The takeaway here? HARDY won't quit. Or, to quote another Quit!! banger, "I DON'T MISS," when a hit is in the crosshairs, he "don't hit nothing but the bull's eye."

No doubt, he has the numbers to back it up. HARDY linked up with Florida Georgia Line after moving to Nashville in the 2010s, and landed his first country No. 1 as a songwriter in 2018 thanks to the duo and Wallen, with the smash "Up Down." As he began building a solo career — releasing a pair of EPs in 2018 (This Ole Boy) and 2019 (Where to Find Me) — he continued delivering chart-topping hits for FGL, Shelton, LOCASH, Wallen, Dierks Bentley, and more. As Quit!! arrives, HARDY boasts 15 No. 1 hits: 11 as a songwriter, and four as an artist.

Along the way, HARDY also established his Hixtape series, a countrified version of a hip-hop mixtape now three volumes deep, bringing together friends and superstars like Keith Urban, Trace Adkins, Thomas Rhett and a host of other stars to collaborate. Not only did Hixtape Vol. 1 land HARDY his first No. 1 as an artist in his own right — the Lauren Alaina and Devin Dawson team-up "ONE BEER" — but it put HARDY's shapeshifting musicality front and center.

"A lot of people ask, 'When did you decide to jump into the rock and roll thing?' HARDY, who uses his last name as his stage name, says. "I feel like I've always dipped my toes in it here and there, and a lot of my songs have been really close to it but not quite there. Hixtape, especially Vol. 1, I was definitely foreshadowing my sound, and I really didn't even know it at the time."

By now, modern country musicians regularly reflect influences from beyond Nashville's confines. But HARDY has played a big role in rock's country crossover, as he gradually showed more of his Mississippi-bred, guitar-riffing roots on his 2020 debut album, A ROCK. He fully embraced them on the 2023 double album, the mockingbird & THE CROW; while the first half has more country-oriented tunes like the Lainey Wilson-featuring murder ballad "wait in the truck," he lets loose on THE CROW.

"THE CROW will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am," he asserts. "It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record."

HARDY has not only been an architect of this genre blending, but also its chief proponent — so much that in 2023, the L.A. Times crowned him "Nashville's nu-metal king." On Quit!!, he cashes in that currency with the gargantuan guitar riffs and bombastic beats popularized by acts like Limp Bizkit, and leans deeper into the rhythms and playful lyricism of hip-hop, a skill he recently flexed at the request of Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre on a hicked-up rendition of Snoop Dogg's G-funk classic "Gin and Juice."

Ironically, the further HARDY gets from straightforward country music, the closer he gets to who he really is as an artist. Below, the chart-topping star details the backstory of Quit!!, his conflicted relationship with the country-music formula, and how he'll continue pushing boundaries within the genre and beyond.

You grew up in the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. What role did music play in your upbringing?

My dad introduced me to rock and roll in general, but it was his era of rock and roll. Whatever you define as classic rock and everything under that umbrella. But music was a big deal in Philadelphia and it still is. There were tons of cover bands, and a lot of [my] buddies were into music. So that had a big influence on me.

I, thankfully, was in that last era of kids that the only time they got to hear a song was on MTV or on the radio. And I remember hearing "In the End" [by] Linkin Park, and then getting Hybrid Theory on CD. I remember the first time I saw [Limp Bizkit's] "Nookie" video on MTV. I was heavily influenced by all that stuff. I'm very thankful that I grew up in the era before the internet was really big.

Were you into country music back then?

Surprisingly, not at all. Not until Eric Church, Brad Paisley, a couple of people started singing about stuff that really piqued my interest. But no, I didn't really listen to much country.

I think the only country that I listened to, if you even call it that, was Charlie Daniels. He played at the Neshoba County Fair. I got to see him twice. But even he was more of, like, you'd almost call it more Southern rock. For some reason, country music at the time didn't do it for me. It took me a long time to get into it.

You recently re-envisioned "Gin and Juice." Were Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre big artists for you when you were younger?

Yeah, especially Snoop. Snoop was in his later years when he started doing more pop stuff. I was a little too young for Doggystyle. I was 4 years old when Doggystyle came out, so my folks weren't letting me listen to that. But I will say, [Dr. Dre's 1992 album] The Chronic and especially [1999's] Chronic II, those records were huge. And anything that Dre touched after that, like all the beats he produced for 50 Cent, and obviously I'm a huge Eminem fan. I mean, all the way up to Kendrick [Lamar]'s early stuff.

I don't know how much they influenced me musically, but I definitely listened to both of them at the time.

You've got so many projects and co-writes and stuff going on, always. Is it easy to pinpoint where your journey to Quit!! began?

I can tell you for a stone-cold fact that "BOOTS" [from A ROCK] is responsible for the album Quit!! That was the first song that I ever wrote that had a breakdown in it. And when I played that live before it came out, people didn't know it, so it was a little different then. But once the song came out, and we started playing it live, it was bigger than "ONE BEER." It was bigger than "REDNECKER." It was the biggest song in our set, and to this day, it's still one of the biggest songs in the set.

But because I love the rock and roll sound so much, that's the song that I was like, Okay, this is working, because these people are losing their s— when we go into this song. So, then, that inspired me to write "SOLD OUT," and once "SOLD OUT" came out, and we started playing that song, that song was even bigger than "BOOTS," and it was heavier than "BOOTS." After "SOLD OUT," it was "JACK," and it's just a snowball of writing heavier songs and having the courage to keep going. "BOOTS" crawled so that Quit!! could run, you know? That was definitely the song that started it all.

The new album builds on the mockingbird & THE CROW and the direction you were heading.

Yeah, I think it builds on it maybe in the sense that there's a lot more screams, and maybe more breakdowns, and it's a little heavier than the mockingbird & THE CROW at times. But it is also very different. There's a lot more, like, pop-punk stuff and, I don't even know what you would call it, post-hardcore-sounding s—.

But all of the rock and roll stuff stands on the shoulders of THE CROW. It will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am. I mean, it definitely teed me up. It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record.

I like that word, courage. It's not a word I expected to hear out of you based on your persona, but that's a very interesting way to phrase it.

No, I mean, the metal and country cultures are very, very, very different. There's never fear, but there's definitely, what's the right way to say that? You know, there's like when we throw like the goat horns and s— on the screen. Country has a big Christian background, and metal is like the exact opposite of that, and those can clash a lot, but there's definitely a little bit of some reserve — it seems to not get too much push back — mixing the two. My mom's not crazy about it, but what can you do?

And you have moments like "wait in the truck," where you're not writing for the party. Do you see yourself pursuing those avenues more often? Does the world want to hear HARDY reflect?

You mean like more of the deeper country stuff?

Correct, yeah.

I hope. That's the s— I love. I feel like they're so few and far between. Like, "wait in the truck," we just got so lucky. I feel like "ONE BEER" was kind of the same. Like, it's gotta be the right day, and the right time, and the right people in the room to really tell a story. It's tough. But I would love to continue to have those cool story songs.

But what I will say is there's a lot of gray area between the black-and-white of HARDY country and HARDY rock and roll. I'm still going to put out country songs. The gray area is that to me and to a lot of people, they're all just HARDY songs. But I have so many songs that I have written that I wanna put out that are so, maybe if they're not storylines, they're even deeper down the rabbit hole of thought-provoking stuff, like "A ROCK," or maybe even "wait in the truck," or even a song I have called "happy," on the last record — just songs that are very, very thought-provoking.

Just trying to push my own boundaries of country music, and not everything is right down the gut, you know, "let's go to radio with it." But just really trying to experiment with what I wanna say with country music. So, yes, there's definitely more of that coming.

You're playing your first headlining stadium gig in September. How has performing in those venues, and anticipating that, informed how you write? Are you writing for the stage?

Yeah, 100 percent. I would say, 75 percent of the time you're writing for the stage — even if it's not for myself, if I'm writing for somebody else — I'm definitely writing for the stage. I cannot tell you how many times I've sat in the room and been like, This s— is going to pop off live! And then try to put the other writers in that headspace.

Like on [Quit!! track] "JIM BOB," when we did the pow-pow-pow! thing, I'm like, just think about how cool it's gonna be live, and living in that headspace, because that's where it all comes to life. That's the end product.

Writing for the stage is something that a lot of people do. And that's why songwriters love going out on the road, is because they go out and they write songs with these artists, but they love watching the show because they get to see what really translates live, and then take that back to the writing room and try to recreate that.

Did that kind of experience have anything to do with you making the move to a marquee artist? Because not all songwriters can make that jump. Or was that always the plan?

Yeah, I mean, it was always that kind of thing. I was fortunate that I got to see Morgan [Wallen] perform "Up Down," and FGL perform a couple of their songs before I made the jump into an artist. I kind of already scratched that itch a little bit.

The Nashville writing scene can seem like a 9-to-5 kind of boring thing. But it doesn't sound that way from the way you describe it.

It's a little bit of both. The funny thing about that is like, if you walk into a publishing company, 10:30, 11 o'clock, whenever people start getting there, it's a bunch of dudes or girls standing around drinking coffee, hanging out. It's like a break room, and then everybody's like, "All right, well, y'all get a good one." And then everybody goes into their own rooms. That part of it is very 9 to 5.

But there is definitely — especially with our group of people, when you get on something that is so special, it's beyond, like, "We're writing a hit today." There's just something that transcends that. I don't know how to describe it, man. That's when it's really, really, really, really great. The Nashville process, that's what it's all about — having those moments in the room where you're like, "This is special," and, like, "We're witnessing something special that is going to affect people on a global or on a nationwide scale."

I remember when we wrote "wait In the truck" and how we were all just gassing each other up because we were like, "Dude, this song is gonna help a lot of people." And that's when the 9 to 5 goes away. We're being creative together, and it's a special thing.

There's been so many moments like that, where you're just so thankful to be a part of a great song, and how hyped everybody is. It's a feeling that's really, really hard to beat.

More Of The Latest Country News & Music

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Koe Wetzel On How New Album '9 Lives' Helped Him Tap Into His Feelings

Katelyn Tarver's "Everyday Is A Winding Road"

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

Amy Grant Shares Where She Keeps Her GRAMMYs

Photo: Rich Fury

list

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Not a Phish phan? No worries. Ahead of their 26-date tour and new album, 'Evolve,' dig into this primer on the music and the subculture of the most popular jam band since the Grateful Dead.

Mainstream rock or pop, Phish are not. While the foursome from Vermont are definitely a jam band, that label does not capture their unique sound and varied influences. Both on record and live, Phish's extended improvisations noodle from reggae and all forms of rock, to bluegrass and funk, with healthy doses of country, blues and jazz.

Like the jam band godfathers the Grateful Dead, Phish built its devoted fanbase not through singles and airplay, but via tireless touring and word of mouth. On some nights — okay most nights — even the band has no clue where their rambling live shows will go. This spontaneity has been Phish's guiding ideology from its earliest days playing college campuses to their annual residency at Madison Square Garden; there is nothing contrived or calculated about a Phish show; instead, the band's filled with surprises and set lists that change more frequently than you change your bedsheets.

For more than 35 years now these four souls have been taking Phish-heads along on this joyous musical ride to unknown soundscapes. Concerts are fueled by passion, not perfection. Ask 10 Phish phans what their favorite live show is from the band’s history and likely each will offer a different answer and argue the reasons for their choice as if it were a thesis defense.

Read more: A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

For Phish, it’s not about awards and accolades. The group has just one GRAMMY nomination and its highest charting single came and record came 30 years ago. In 1994, Billy Breathes peaked at No. 7 on the Billboard 200; its lead single "Free" hit No. 24 on the Billboard Hot Modern Rock charts and No. 11 on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart.

What attracts people to Phish's music and subculture is the mood, the groove and the community; that’s why the band perennially have been one of the highest grossing live acts throughout their career. The band is also part of American pop culture: They have a Ben & Jerry’s flavor (Phish food), have appeared on "The Simpsons" and been parodied on "South Park."

This spring, Phish became only the second band (after U2) to perform at the Sphere in Las Vegas. Over the weekend of April 20, the foursome played four shows with a completely different set each night. The final show on Sunday evening featured an epic second set, even by Phish standards: the band performed for nearly two hours and jammed on for 34-minutes on "Down with Disease."

Surprises like this musical meandering abound at Phish shows and it’s another reason fans shell out a hefty chunk of their pay cheques to see them live again and again and again; it’s also what makes attending one of their concerts a unique experience. The relationship between the band and these devotees is symbiotic. Both inspire and guide the other.

Phish does not take itself too seriously. This is reflected in their songs, their artistic approach and their love of a good prank. Ready to go Phishing? Not the dictionary adjective that conjures negative connotations of scams and identity theft, but rather, a new word we suggest adding to the Urban Dictionary meaning to take a deep dive into the weird and wonderful world of Phish.

In advance of the band’s 26-date tour that starts with a three-night run in Mansfield, Massachusetts to promote Evolve — its 16th studio record that arrives July 12 — GRAMMY.com offers a lowdown on these musical merrymakers. Read on for a guide to appreciating and approaching Phish's lingo, lore, and lengthy discography.

Phish 101

Before the band had a name, a following, or conferences and university courses dedicated to the study of their music, they were just a bunch of college kids jamming in their dorm. The original members of the band met while attending the University of Vermont in Burlington. Initially formed as a trio in 1983 that featured guitarists Trey Anastasio and Jeff Holdsworth, along with drummer Jon Fishman. Bassist Mike Gordon joined that fall. In 1985, keyboardist Page McConnell was added and Holdsworth left. Today, it's these four (Anastasio, Gordon, Fishman and McConnell) that comprise Phish.

Junta, the band’s self-released debut arrived on cassette in 1989, followed by Lawn Boy the next year on Absolute A Go Go Records. The industry buzz created by their live shows then led to a multi-album deal with Elektra Records, who, in 1992, released their major label debut A Picture of Nectar, along with reissues of Junta and Lawn Boy.

What’s with the name? Everyone loves a good band name origin story, and there are often several versions of Phish's. The simplest and most popular one cited is that Fishman was asked at an early gig for the band’s name and thought they were asking for his name, so replied with his college nickname, "Fish." It stuck and they just changed the spelling.

A Lesson In Lingo: 4 Phish Phrases

Next up on the Phish syllabus is a lingo lesson in lingo. Overhear a pair of Phish fanatics chatting in a coffee shop, and you’ll wonder if they are speaking a different language. These devotees have developed their own lingo to express their love for all things Phish. Here’s a quick primer to help you converse with phans as if you know what you are talking about.

First, phans label each era of the band a number and these labels describe when their love of Phish began: 1.0 refers to the band’s beginnings until its first break in 2000; 2.0 is a short period and a small cohort of fans that starts when Phish returned from its first hiatus in 2002 and ends before they officially broke up in 2004. Finally, 3.0 refers to new converts: fans who discovered the band only after they reunited for good in 2009.

As this schooling on Phish continues, here are four words to drop into a conversation with a Phish fan to make you sound educated. "Noob" is a condescending word referring to a newbie, like post-2009 phans. A "chomper" is someone who talks during songs at a Phish concert (definitely a no-no). "Spunion" is someone whose appearance, actions and speech indicate they’ve taken way too many drugs. Finally, "hose" is a free-flowing improvisational jam where the music feels like it just flows directly into the listener’s ears.

Down On The Farm: Hits & A Few Phan Favorites

From the 2000 record of the same name, "Farmhouse" is one of the few Phish songs that made a splash beyond just their fans thanks to this radio-friendly chorus: "I never ever saw the Northern lights/I never really heard of cluster flies/ I never ever saw the stars so bright/ In the farmhouse, things will be alright." Besides this earworm, the ninth record from the band also featured another one of its biggest charting radio hits: "Heavy Things," which reached No. 29 on Billboard’s Adult Top 40 chart and No. 2 on the Adult Alternative Songs charts.

Some other key studio tracks to explore and listen to that show the depth and breadth of the band’s talents include: "Golgi Apparatus," "Chalkdust," "Torture," "Sample in a Jar," "Character Zero" and "Sand."

Into The Studio: A Choice Phish Records

Phish have released 20 studio albums and 53 live records. That’s a lot of music to sift through for any newbie. Three key albums to help understand and get into the band include: A Picture of Nectar (their major-label debut from 1992 that was certified gold), Hoist (1994) and The Story of the Ghost (1998), recorded at famed Bearsville Studios in in Woodstock, NY - a record Trey Anastasio described as "cow-funk." Listen carefully to this trio of records and you’ll come away from these deep dives either loving the band and ready to take the next step on this phishing trip or not.

Make sure to also check out the conceptual album Rift. This follow-up to their major-label debut is a fan favorite and also a critical darling. It’s possibly the band’s greatest studio creation, but it’s also an acquired taste. Rift follows the story of a man who dreams about the rift in his relationship with his girlfriend. The listener follows this protagonist on a dark and heavy ride as his emotional journey turns from a pleasant dream to a nightmare. The narrative is told backed by a sonic palette that showcases all of Phish’ colors and musical influences: from jazz and blues to psychedelic rock and funk.

Go See Phish Live

As Neil Young sang in "Union Man," that is often-quoted by concert lovers, "live music is better bumper stickers should be issued." Phish subscribe to this mantra and are known to plaster their cars in bumper stickers. The centerpiece of a Phish show is extended jams and the communion between Phish fans, but their concerts also feature amazing light shows, props, and pranks.

To get a sense of what attending a Phish concert is like, start with the six-disc set Hampton Comes Alive. Released Nov. 23, 1999, the collection consists of two concerts in their entirety captured at the Hampton Coliseum in Hampton, Virginia in 1998. The title plays on Frampton Comes Alive! — one of the best-selling live albums of all time.

In the band’s early days before the Internet came of age, bootleg tapes abounded. Trading these — just like Grateful Dead fans do — was always a part of Phish culture. LivePhish captured all of the band’s live shows. This is now an Android app where you can stream shows, past and present. Mere minutes after each Phish concert ends, the newest show is uploaded.

Before the streaming age, the band frequently released CDs up to six discs in length (most Phish concerts run more than three hours). One of these essential listening live releases is Darien Lake from Sept. 14, 2000 that includes a cover of Neil Young’s "Albuquerque."

Order Up The Baker’s Dozen

For Phish fans, the 13 concerts dubbed The Baker’s Dozen are pure bliss. The residency occurred at the Manhattan mecca from July 21 to Aug. 6, 2017. Every night featured a different set list (26 total sets as they played two each night). No song was repeated and each night had a theme.

Over the course of 13 shows, Phish played 237 songs. A highlight of The Baker’s Dozen was a 30-minute jam of "Lawn Boy" — a song that usually clocks in under four minutes.

Cover Me

Many consider the group the greatest cover band on earth, so go down the Phish YouTube rabbit hole and what matters at this moment in your life is sure to get neglected for a while.

An understanding of Phish's many collaborations and covers tis also essential to better appreciate the band. Phish has paid homage to everyone from classic rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, to Frank Zappa and the Talking Heads. Collabs include: Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, and weird as it sounds, even Jay-Z, who the band invited on stage during a Brooklyn gig in 2004, to sing-along on the 24-time GRAMMY-winner’s hits: "99 Problems" and "Big Pimpin.’"

Trick Or Treat Tributes & Auld Lang Syne Shenanigans

Halloween shows always feature musical costumes where Phish plays another artist’s album from front to back. The Beatles' White Album in 1994 is especially good and the first time the band premiered this concept. Many fans claim the 1998 Halloween show where the band covered the Velvet Underground’s Loaded is one of the most underrated and was mind blowing. But the best might be from 2018 when they invented a fake Scandinavian synth-rock outfit called Kasvot Växt.

For years, Phish have celebrated another year come and gone along with their fans, often playing a string of shows leading up to New Year’s Eve. Pranks are always a part of these special occasion gigs and there's often a theme with stages being transformed to transport their phlock to other realms.

Many of Phish’ most legendary end-of-year celebratory concerts occurred in New York City at Madison Square Garden where they’ve performed to close out the year 15 times. One of the most memorable saw the band "send in the clones" on Dec. 31, 2019, to ring in another new year.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'