Since the word "jazz" was coined—most likely by white Americans at the beginning of the 20th century—artists have been resisting it. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie didn't appreciate the designation in the least, calling their offerings "modern music." The multi-reedist Yusef Lateef once spent a whole UCLA lecture taking the dictionary to task about it. If one called Max Roach a jazz musician, he was liable to come to blows. "You can have this word," John Coltrane declared in 1962, "along with many others that have been foisted upon us."

Almost 60 years later, that "foisting" continues unabated—and Tyshawn Sorey is beyond done with it.

Some of the multi-instrumentalist and composer's work resembles jazz. Sometimes it sounds more like classical. But the truth is that Sorey can freely move between those spheres—or ignore them entirely. "To deny something that is a part of my musical experiences or my life experiences is to be completely dishonest with anything that I put out artistically," the multi-instrumentalist and composer tells GRAMMY.com. "I don't feel like I have to be necessarily in one of those areas whenever I'm creating music."

Sorey isn't alone. Granted, his colleagues, like trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, flutist Nicole Mitchell, bassist Linda May Han Oh, and drummer-rapper Kassa Overall, don't uniformly reject the word "jazz." But when attempting to encompass their visions—avant-garde explorations, large-scale chamber works, acrobatic MC flow—the term falls short. These five artists have mastered the language so they can bend it to their will—or even cross-pollinate it with other languages entirely.

In honor of Jazz Appreciation Month beginning on April 1, we can certainly acknowledge and love the traditionalists—those for whom "jazz" isn't a slight. At the same time, let’s honor those who explode that description, leading the charge of "modern music" in the 21st century.

For those uninitiated in this world—or who mistakenly think the fusion era was the end of the line—here are five artists who are pushing the genre forward in 2021.

A Composer Beyond Descriptors: Tyshawn Sorey

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//mSmGm-jmgkk' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

For as good an entryway as any into Tyshawn Sorey's world, watch his 2019 improvisational set with gayageum player Do Yeon Kim at the New England Conservatory. Therein, Sorey plays every inch of the kit, whether manipulating snare wires with his hands or dragging a stick across the skin of a drum.

But even in this "out" format, Sorey isn't fomenting discord; he’s doing the opposite. "It's not like he does anything that's disordered," his longtime creative partner, pianist Vijay Iyer, told GRAMMY.com recently. "Actually, everything he does is generating order."

Sorey agrees. "I think his response is accurate in that every decision I make is a compositional decision, and it's informed by the people I’m performing with," he says. "It just all comes down to really the amount of care that goes into creating the spontaneous work with whoever you're performing with." This could range in number, he adds, from a duo to 15 musicians.

As a drummer, Sorey is a multidimensional force. "Playing with Tyshawn is like being on stage with the ocean," flutist Claire Chase told The New York Times in 2021. "You're there with the ocean and it’s serene, and also dangerous and terrifying." But he's also played trombone and piano for decades, and he composes for the concert hall.

"I want to do something that celebrates the idea of genre mobility," Sorey says. "For me, there's no such thing as a jazz composer or even the classical composers. People just wrote the music they wrote and they have a right to engage and pursue it."

To that end, Sorey isn't just pushing jazz forward; he's pushing everything musical forward. Approach his body of work without preconceived attitudes and you'll get an ocean in return.

Three entryways:

The Inner Spectrum of Variables, 2016

Verisimilitude, 2017

Unfiltered, 2020

A Flutist Elevating Her Instrument: Nicole Mitchell

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//XrECd3eFsYA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The flute occupies a slightly awkward space in jazz. Despite its importance to Cuban music and a number of phenomenal flutists in the genre—Herbie Mann, Hubert Laws, Rahsaan Roland Kirk—it still has a tertiary role compared to the saxophone and trumpet.

Flute master Nicole Mitchell is fully aware of this precedent. As such, she approaches her playing from a unique angle, valuing personal feeling and group cooperation above all else.

"I tend to like the lower range of the instrument—the richer, darker, lower range," Mitchell tells GRAMMY.com. "I mean, I can play virtuosically and everything, but that's not as much the focus for me when I’m dealing with my ensembles. I’m trying to express what the whole range of human emotions are."

Those groups include the Black Earth Ensemble, which has braided Black forms from swing to avant-garde jazz for more than two decades, and the Artifacts Trio where Mitchell dabbles in electronics.

Twenty years since her debut album, Vision Quest, how does Mitchell view the long arc of her creative development? "I've explored spaces that have been difficult," she says. "I’ve learned to embrace what I call the edge of beauty and embrace the uncomfortable because I feel it’s in those spaces that we have a possibility for transformation."

But the throughline of her work, she says, is a celebration of contemporary African-American culture. As such, don't bottle Mitchell's output into "jazz," but hear it as a jolt of Blackness in all its mystery, complexity and joy.

Three entryways:

Afrika Rising, 2002

Black Unstoppable, 2007

Maroon Cloud, 2017

A Master Bassist & Musical Backbone: Linda May Han Oh

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//MWuvYeAdlYw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Linda May Han Oh arrived with 2008's Entry, a unique opening statement for a musician in her early twenties. "That was a bold step, first of all, for a bass player to make an album as a leader at that age," Iyer said. "There aren't that many records that are trumpet, bass and drums."

The format wasn't simply to be brazen. Rather, it was simply a documentation of where Oh's head was at the time—a photographic entry. "I just wanted to do something that didn't show every side of me," she explains to GRAMMY.com. "It was one document of what was there at the time."

From that record, which featured trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and drummer Obed Calvaire, Oh's purview expanded dramatically. Since then, she’s led a quartet (2013’s Sun Pictures) and a quintet (2012's Initial Here) and recorded with heavyweights from pianist Florian Weber to guitarist Pat Metheny.

But Oh is not just a small-group leader or a sidewoman. Aventurine, her luminescent chamber work from 2019, is her most monumental work to date as a full-fledged composer. What's the through-line between all of her work, as the backbone of so many ensembles?

"I would say to be in the moment," she says. "That's the number one priority. Whatever the moment calls for is the first thing." With a litany of projects on the horizon for 2021 and beyond—big bands, small bands, scoring a documentary—it’s clear that now is Oh's moment.

Three entryways:

Entry, 2008

Walk Against Wind, 2017

Aventurine, 2019

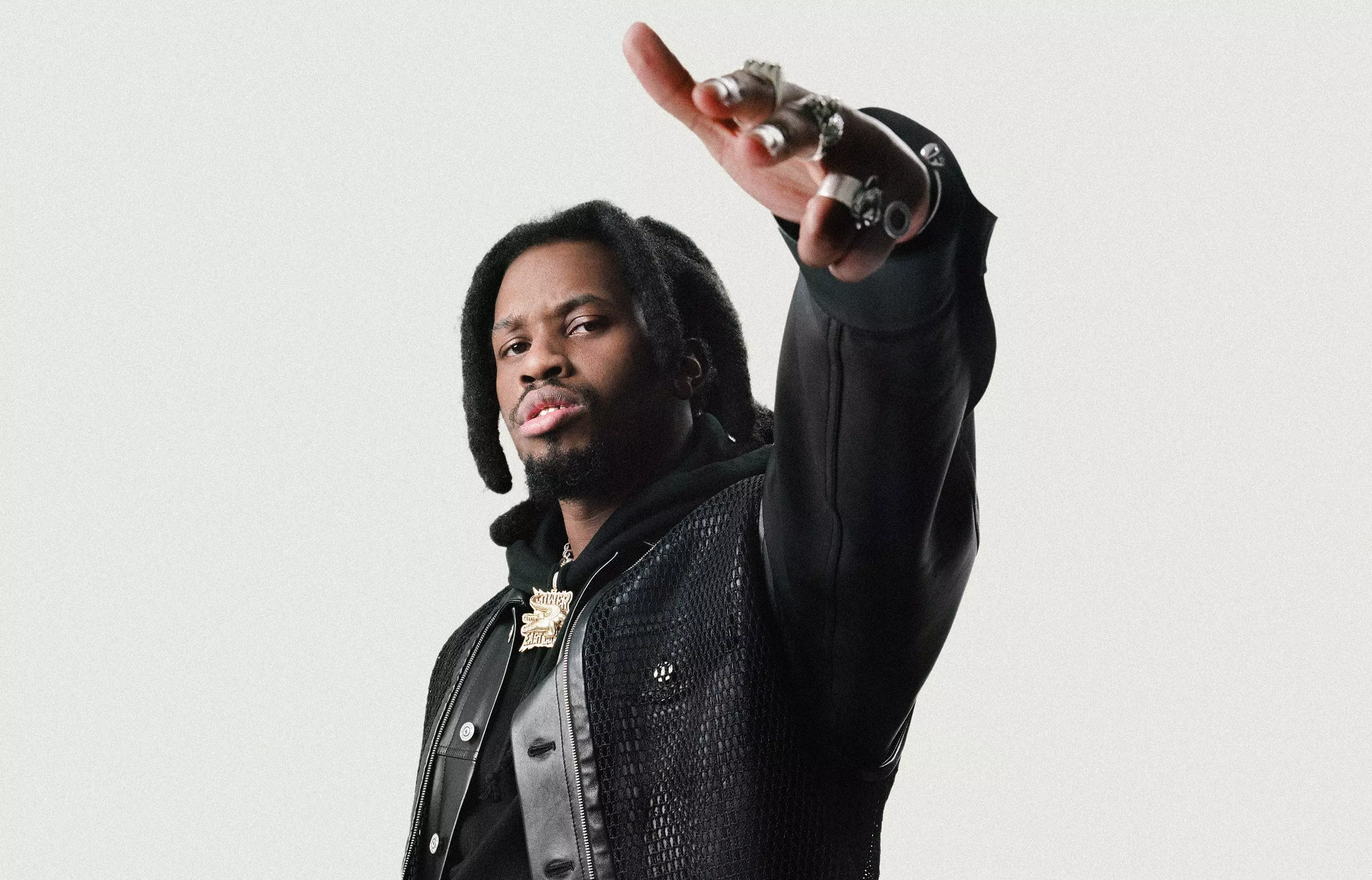

A Pathfinder Through The Modern Avant-Garde: Ambrose Akinmusire

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//swcSU71gixw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The common line in jazz is that it went as "out" as it could possibly go at the end of John Coltrane's life. This is reductive. The avant-garde has never stopped being fertile soil, and Exhibit A of this reality is the Art Ensemble of Chicago—which was a young Ambrose Akinmusire’s first live jazz sighting.

"That was my impression of jazz," the GRAMMY-nominated trumpeter from Oakland, California tells GRAMMY.com about the boundary-exploding group, which blended free jazz with live performance art. "And a lot of people in the Bay Area playing with Don Cherry and Joseph Jarman and whatnot. So, I think my door was a little different than the average person who sits down and learns about jazz theory."

One of the most compelling trumpeters alive, Akinmusire plumbs fresh territory by considering the social context first. "My mentors showed me records," he recalls. "They weren't like, 'Hey man, check out 'Giant Steps' because of this cool progression that moves in major thirds. It was more like, 'He did this during a time of social unrest.' It was the meaning behind stuff."

Akinmusire joins his frequent collaborator, the pianist Jason Moran, as one of many ambitious conceptualists in his field. But his six albums as a leader—most of them on Blue Note—are thrilling even without backstory or explanation. That clean, pained, incisive tone will tell you everything you need to know.

Three entryways:

When The Heart Emerges Glistening, 2011

A Rift in Decorum: Live at the Village Vanguard, 2017

On the Tender Spot of Every Calloused Moment, 2020

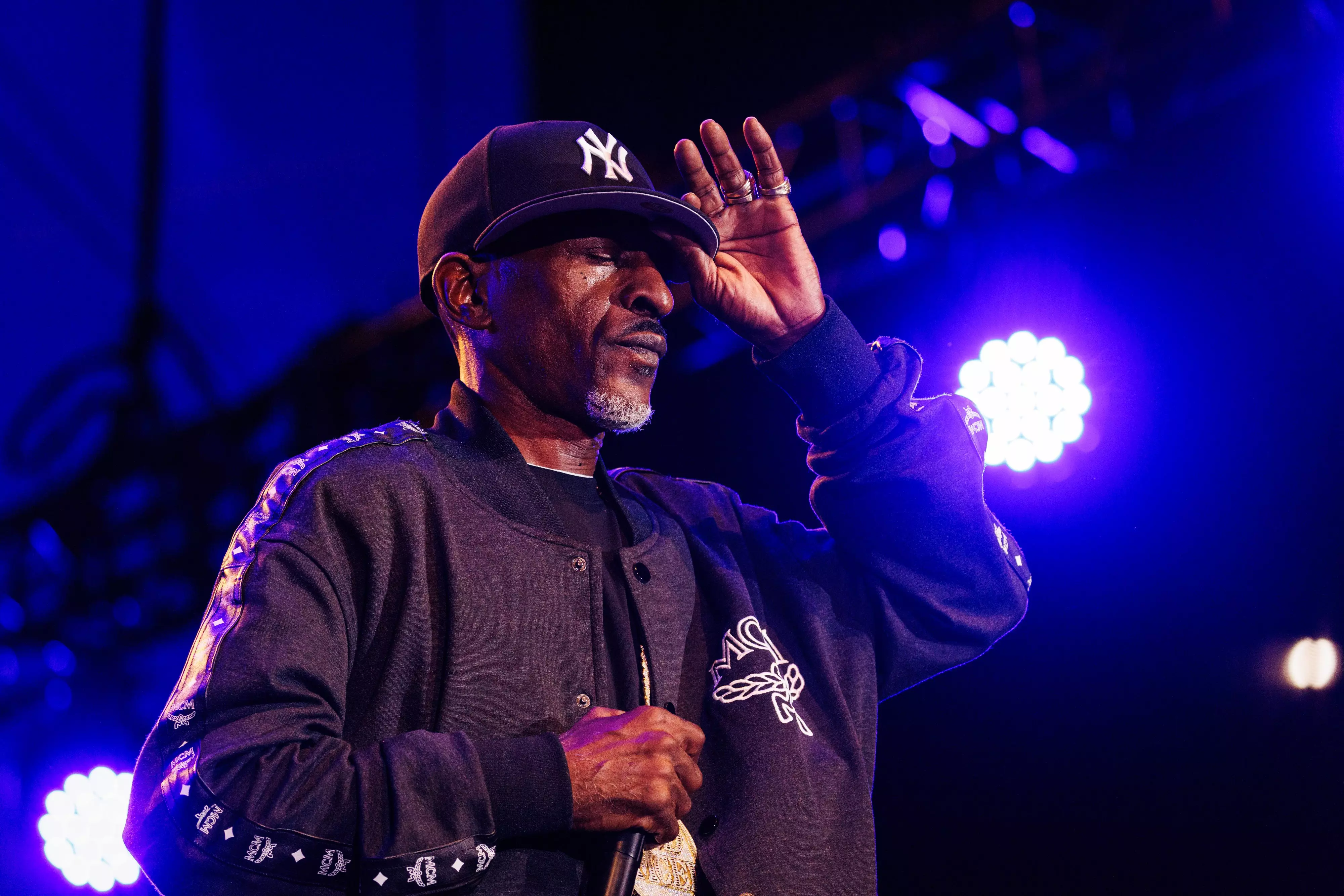

An Intrepid Jazz-Rap Collider: Kassa Overall

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//GGMWRyghsBI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Kassa Overall is tired of interviews about how he can rap and play drums. The idea that they're two wildly divergent things is getting a little strange.

"I've talked about this for two albums now," the GRAMMY-nominated musician tells GRAMMY.com with a hint of exhaustion. "I ran that cycle in my head. I'm not so much trying to prove the point anymore that these things can go together or not go together. I just want to make the dopest s***."

Across two studio albums and two mixtapes, Overall has less blended jazz and hip-hop than crashed them like cars. The ensuing mess, he hopes, will show the two forms aren't at all dissimilar.

"I think that's the secret: not blending them up like a smoothie but putting them together like a collage," he told Tidal Magazine in 2020 while discussing Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly. "They're from the same tree as far as where they come from, which is black music in America. You don’t have to over-mix them. It goes together already."

Overall is about to drop SHADES OF FLU 2, his latest collage of Blue Note samples and boom-bap beats, on Friday. He also wants to bring his craft to the stage—which, given that hip-hop and jazz are two of the most viscerally exciting genres to see live, might mean he has a live monster on his hands.

Still, Overall is toying with the idea of abandoning what he calls "the jazz-hip-hop thing."

"There [are] so many other forms of music that are important, whether they be other African-based genres from other countries or European classical music or whatever,” Overall says. “Maybe we could get away from the idea of even genre, right?"

Three entryways:

Go Get Ice Cream And Listen To Jazz, 2019

I Think I’m Good, 2020

SHADES OF FLU, 2020