Photos (L-R): Paul Natkin/WireImage, Gary Miller/Getty Images, Chris Walter/WireImage, Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

feature

Songbook: A Guide To Willie Nelson's Voluminous Discography, From Outlaw Country To Jazzy Material & Beyond

Prodigious songwriter, interpreter and national treasure Willie Nelson has released dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on who you ask. Still, a few key entryways and rabbit holes can help you get a handle on this foundational country figure.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond.

Cue up almost any Willie Nelson performance from the last 10 years, and you'll find something intriguing. Many other country greats are tight and precise onstage; Nelson is decidedly not.

While his Family band easily catches a groove on well-worn classics like "Family Bible," "Crazy" and "Funny How Time Slips Away," our permanently bandana-ed and pigtailed protagonist is attuned to deeper and stranger rhythmic dimensions. A Willie Nelson show is a particular kind of miasma — at times, it coheres; at times, it hovers almost beatlessly.

Sometimes, Nelson’s famously jazz-inflected syncopation threatens to swing him off the road — he'll strike his famously battered and weathered classical guitar, Trigger, at a moment that seems jarringly off the beat. His light and flinty voice has developed distinguished cracks and fissures with age. But if you're disappointed by his relative lack of polish, you're not just missing the point — you're missing the beauty.

First, nobody has ever picked up a guitar and sang a song like Nelson. The gods only made one of him, and the most fabulously expensive guitar on the market could never sound like Trigger. Second, the soul of country music is impactful storytelling and direct emotional transference, and nobody wields those twin abilities like Nelson, both as a songwriter and interpreter.

Indeed, without him as its cockeyed embodiment and one of its foundational figures, the world of country music would be unrecognizable — period.

Despite a few minor off-ramps during his almost seven-decade career, Nelson has built an astonishing body of work not via overhauling or reinvention, but becoming more himself every year. With every release, he digs deeper into his time-tested toolbox and aesthetic — often to heartening, comforting, and wizening results.

You don't approach the recently released A Beautiful Time, Nelson's fourth album in two years, for left turns; you do so because you want to know what the Beatles' "With a Little Help From My Friends" and Leonard Cohen's "Tower of Song" mean to him — as well as the state of his songwriting.

While the resin-caked hayseed vibe Nelson has embraced since the '70s may be a far cry from his crop-topped beginnings, you can drop the needle on any decade and hear an essentially unchanged artist and person. Whether he's channeling George Gershwin and crooning Broadway tunes, or running from the IRS on record — or even making reggae-inspired music, as on 1995's Countryman — Willie is Willie is Willie.

That said, the 10-time GRAMMY winner and 53-time nominee has either dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on how you count them. Where does one possibly begin? Given that he doesn't really have specific, delineated eras, it's more helpful to cherry pick the most essential albums, decade by decade, while still noting relatively minor entries of interest.

Let's go places we've never been, and see things we may never see again — in this edition of Songbook.

Listen to GRAMMY.com’s Songbook: An Essential Guide To Willie Nelson playlist on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

The 1960s

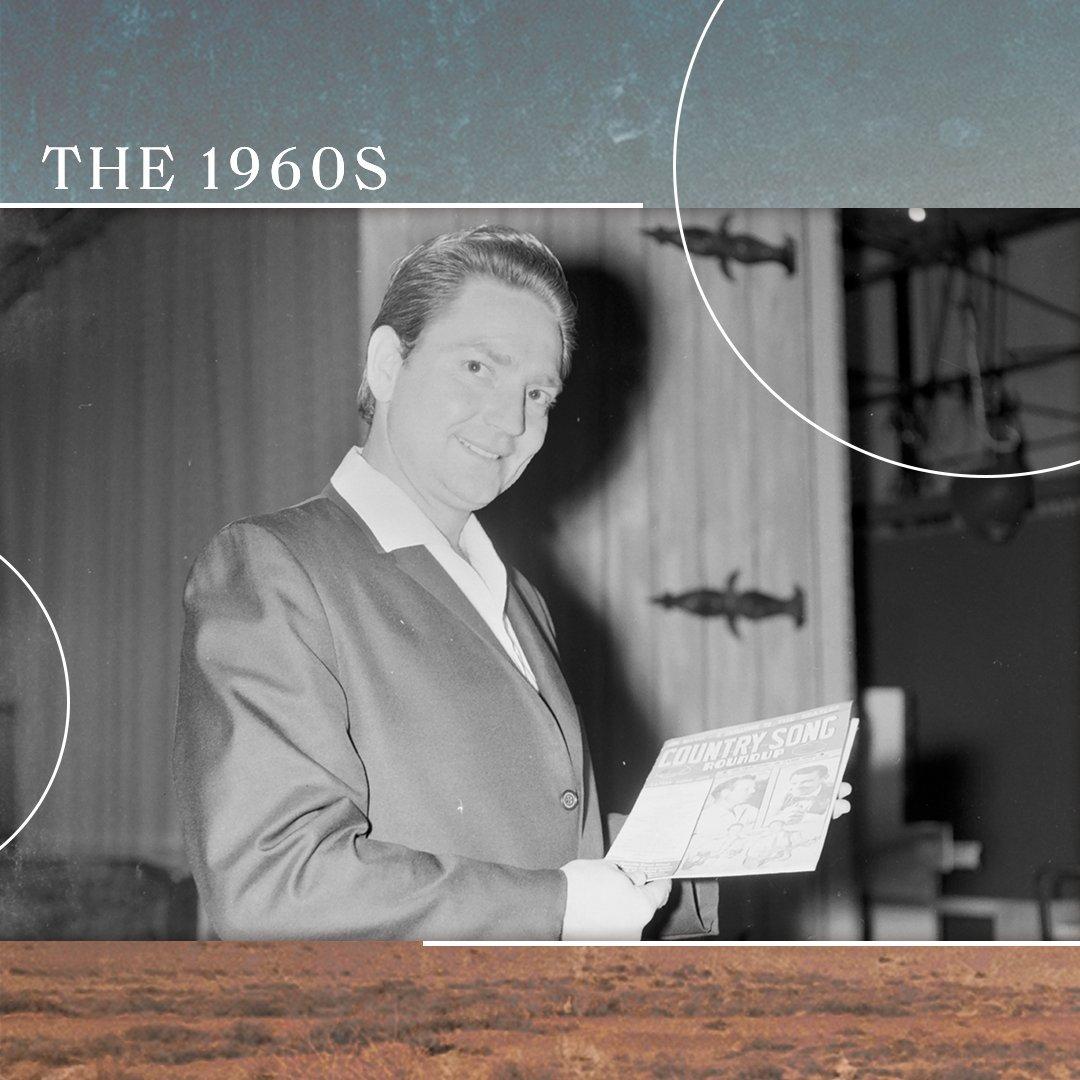

Willie Nelson backstage at "Arizona Hayride" TV show in November, 1964, in Phoenix, Arizona | Photo: Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

While Nelson made his first recordings in the mid-1950s, his discography began in earnest in 1962, with his debut album …And Then I Wrote.

…And Then I Wrote is absolutely worth hearing for its decadent production, introduction of Nelson's Django Reinhardt-inspired nylon-string picking, and key early compositions like "Funny How Time Slips Away" and "Crazy."

The baby-faced country crooner on the cover was in for the adventure of a lifetime. Listen to …And Then I Wrote, consider how Nelson's voice is pretty much the same 60 years on — albeit weathered by age and weed smoke — and you'll realize he essentially came out fully formed.

Do you dig the songs on …And Then I Wrote, but don’t like the semi-excessive reverb and instrumentation typical of Nashville back then? Head for 1965's Country Willie: His Own Songs for alternate versions of tracks like "Funny How Time Slips Away," "Mr. Record Man," and cuts from his second album, 1963's Here's Willie Nelson. But all in all, seek out 1973's The Best of Willie Nelson for a handy sampler platter from his first decade on record.

The 1970s

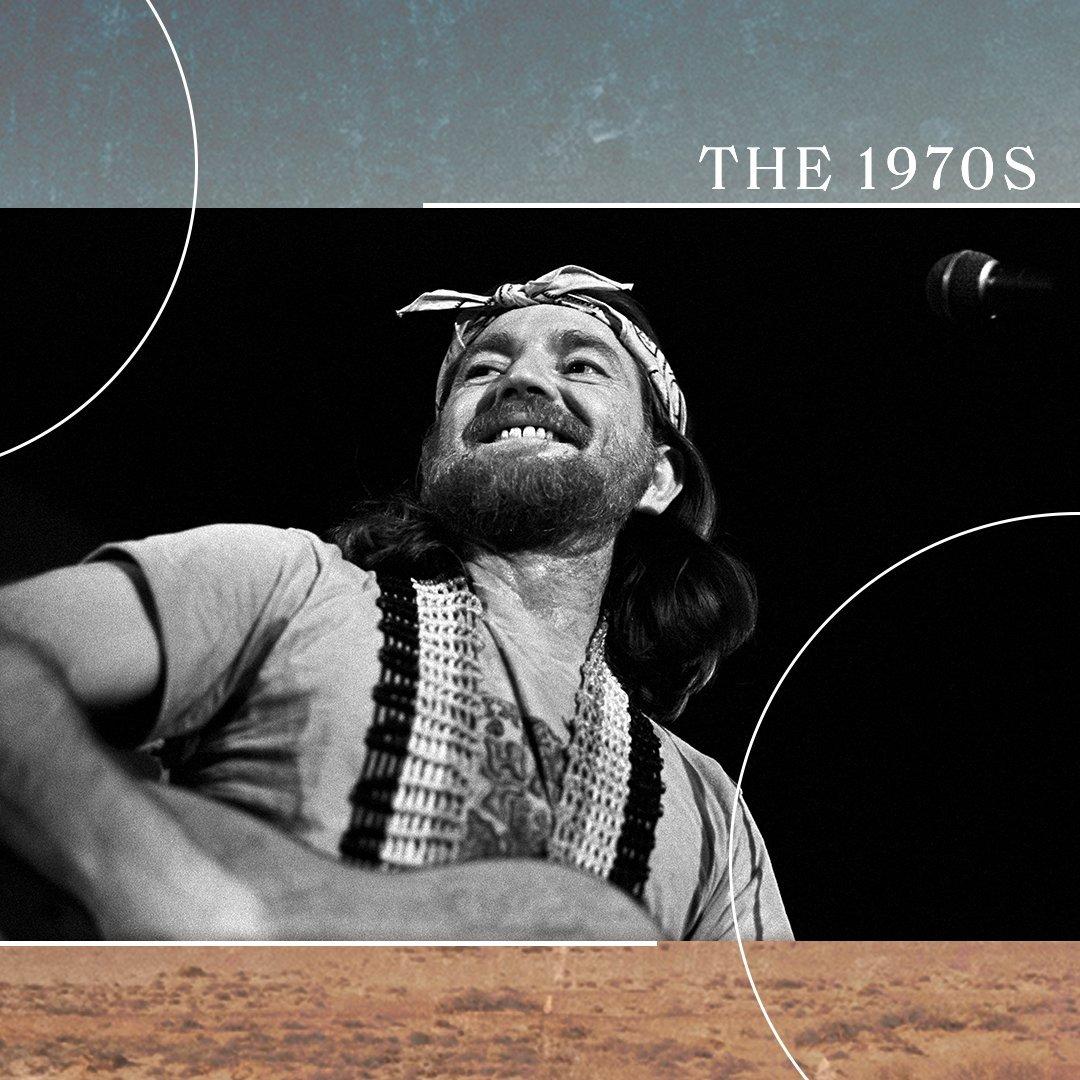

*Willie Nelson performs at the Great Southeast Music Hall on October 27, 1975 in Atlanta, Georgia | Photo: Tom Hill/Getty Images*

Forged and rebirthed by a ranch fire and divorce — not to mention professional bumps in the road — Nelson entered the 1970s with his first masterpiece: 1971's Yesterday's Wine, which contains classics like "Family Bible" and the title track.

Begin your trawling through Nelson's '70s with that record, then follow up with his 1973 breakthrough, Shotgun Willie, whose sound, attitude and songs helped forge the "outlaw country" subgenre. 1974's slightly less discussed Phases and Stages is a heady exploration of a marriage’s unraveling.

Then drop the needle on 1975's Red Headed Stranger, which further cemented Nelson's reputation as an outlaw-country mainstay and contained his immortal version of Fred Rose's "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain." (Talk about making a shopworn song your own!)

If you want a more raucous Nelson offering from this decade, seek out 1976's The Troublemaker, a rough-and-tumble collection of traditional songs.

1977's To Lefty From Willie, a tribute to country singer Lefty Frizzell, is Nelson's first album-length tip of the hat to another artist — he'd later do the same for Ray Price and George Gershwin. And 1978's Waylon and Willie is worth engaging with simply to hear two titans appear on the same record.

The other 1970s entry you must hear is Stardust, which veers away from Nelson's outlaw-country image in favor of jazzy renditions of traditional pop songs, like "Unchained Melody," "All of Me," "Moonlight in Vermont," and — most famously — "Georgia on My Mind."

Given there has never been a jazzier country artist than Nelson, Stardust is a pivot point in his discography by concept alone — one that shows the true depths of his artistry. Seek it out for that reason, and stay for the luminous music.

The 1980s

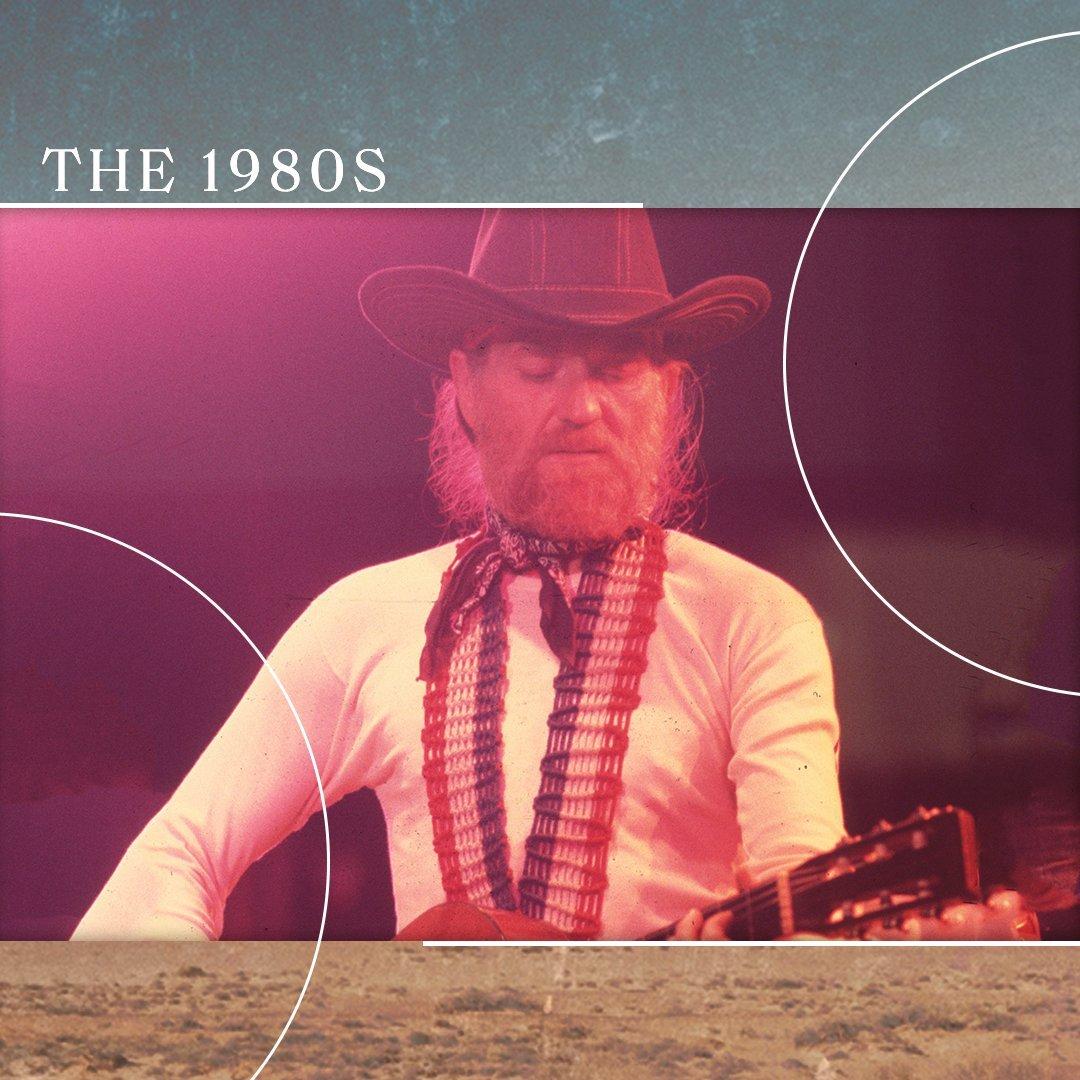

*Willie Nelson performs in 1980 | Photo: Chris Walter/WireImage*

Nelson kicked off the '80s with San Antonio Rose, a collaborative album with Ray Price that illustrated the profound bond between two foundational country figures. Also released in 1980, Family Bible was a duet album with Nelson's sister, pianist Bobbie, who passed away in 2022.

A successor of sorts to 1979's covers album Sings Kristofferson, Music From Songwriter was a duet between the pair. It also soundtracked the titular, well-recieved 1984 film, which starred both men.

The one drop-dead essential Nelson album of the decade, though, is 1983's Pancho & Lefty, his inspired team-up with fellow outlaw-countryman Merle Haggard.

The album featured unforgettable tunes like the Townes Van Zandt-penned title track — a narrative about a wanderer and Mexican "bandit boy" — as well as Haggard's "Reasons to Quit" and Jesse Ashlock's "Still Water Runs the Deepest." It also spawned multiple sequels, from 1987's Seashores of Old Mexico to 2015's Django & Jimmie.

The 1990s

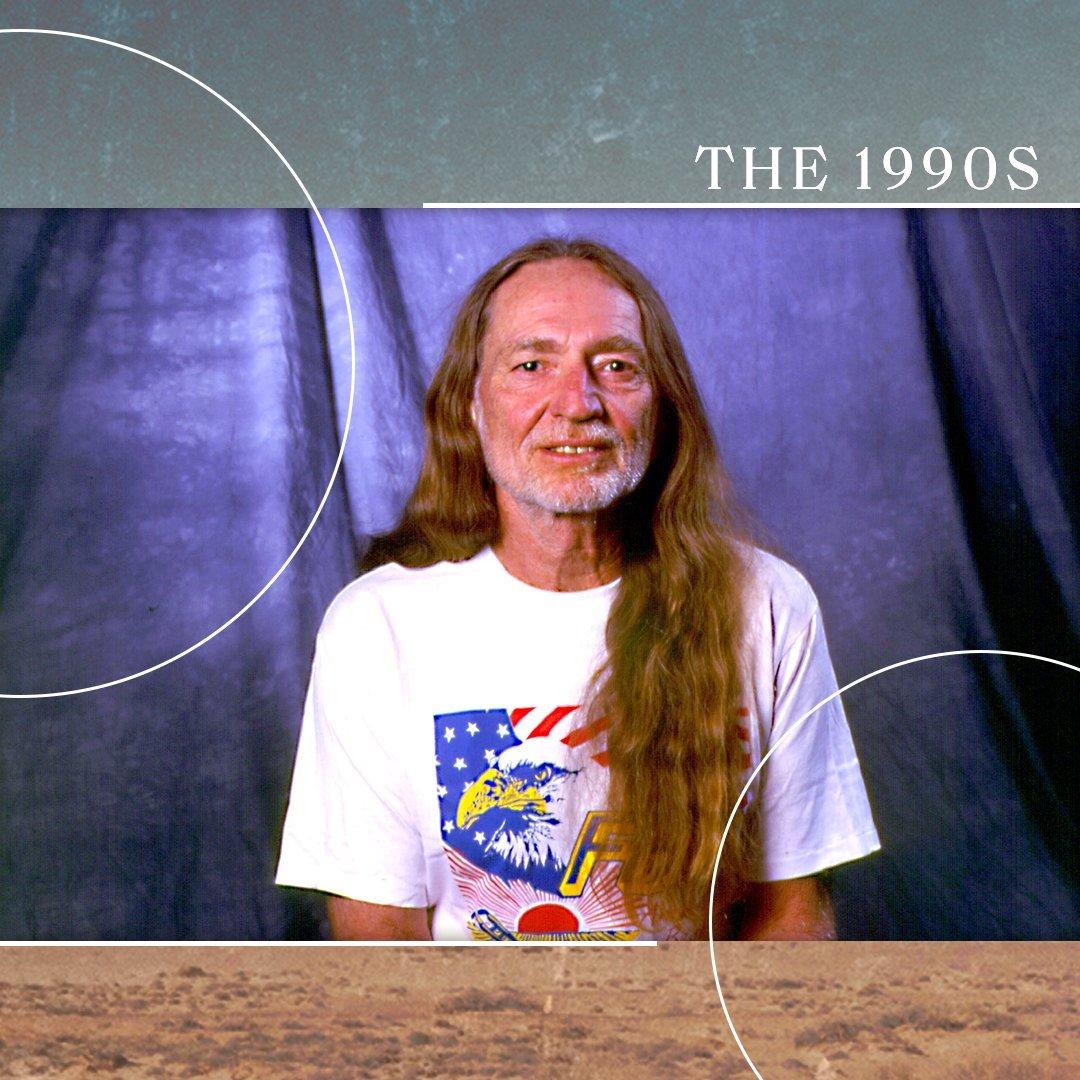

*Willie Nelson in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1994 | Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImage*

Nelson had a beyond rocky start to the decade: in 1990, the Internal Revenue Service seized most of his assets, claiming he owed a whopping $16 million. Long story short, he recorded Who'll Buy My Memories: The IRS Tapes to pay off part of the debt.

Although the album was well-received, it's safe to say it exists more of a reminder of this bizarre yarn than a standalone album worth cherishing. (Thank goodness Trigger survived the property seizure — Nelson's daughter, Lana, shipped it to him in Hawaii.)

A far more essential '90s Nelson listen is the haunting, stripped-down, Spanish-influenced Spirit, a quintessential "real heads only" album.

Featuring fiddler Johnny Gimble of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Spirit consists solely of crepuscular, yearning originals, like "Your Memory Won't Die in My Grave," "Too Sick to Pray" and "I Guess I've Come to Live Here in Your Eyes."

Also of interest from this decade in Nelson's discography: Teatro, which Daniel Lanois recorded in an old movie theater in Oxnard, California and features vocal contributions from the estimable Emmylou Harris.

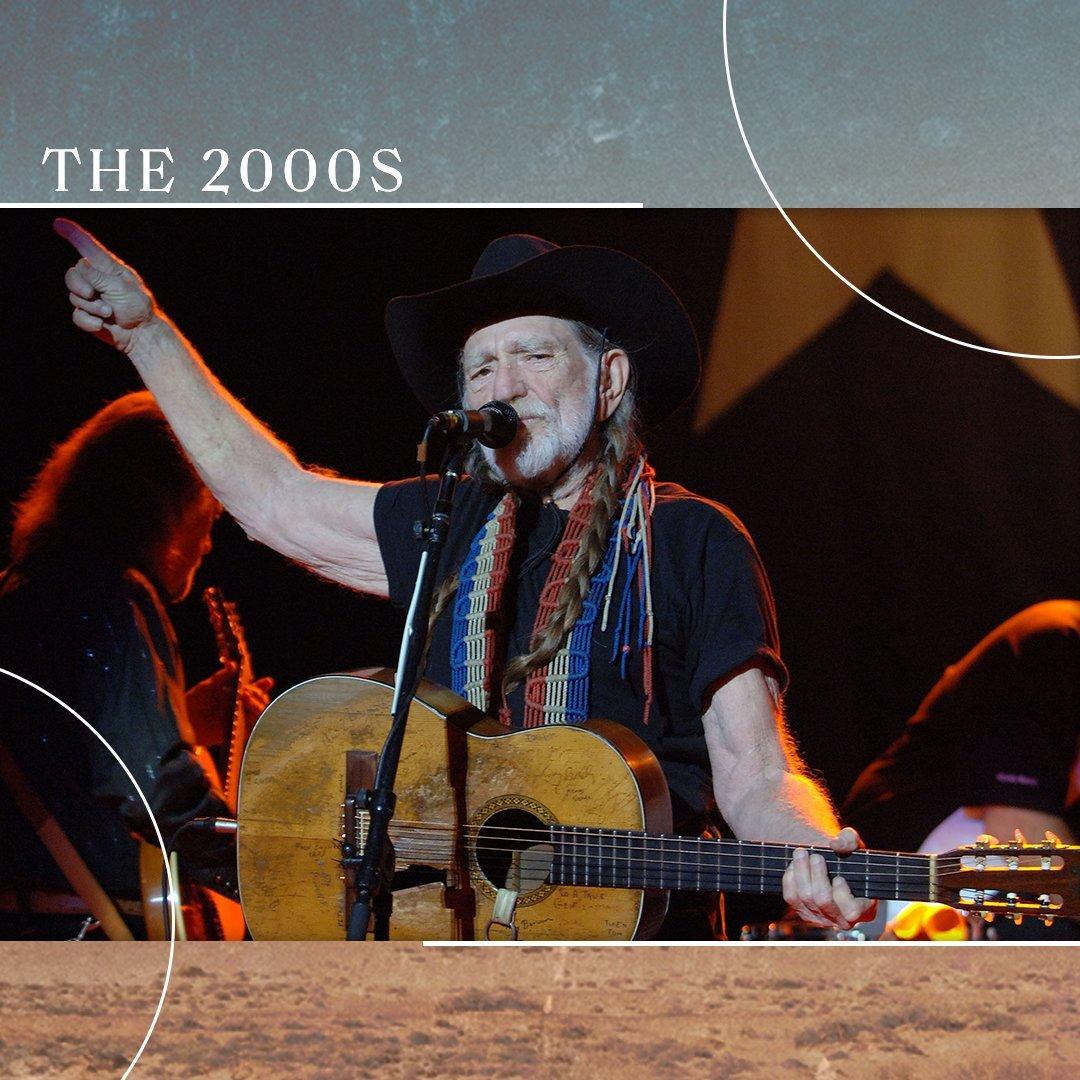

The 2000s

*Willie Nelson performs at The Mizner Park Ampitheatre in Boca Raton, Florida, in 2006 | Photo: Larry Marano/Getty Images*

In the young millennium, Nelson hit the road even harder than he did in the '90s, and collaborated with artists as divergent as Toby Keith ("Beer for My Horses"), Toots and the Maytals ("She is Still Moving to Me," "I'm a Worried Man") and Wynton Marsalis (2008's Two Men With the Blues).

The 2000s are also important in Nelson's development as they marked the start of his partnership with the two-time GRAMMY-winning producer Buddy Cannon. Their inaugural project was 2008's Moment of Forever, and Cannon produces or co-produces Nelson's yearly (or, in some cases, bi-yearly) albums to this day.

Other notable selections from this decade include 2006's Songbird, with Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, and 2007's western-swing excursion Last of the Breed, featuring the triple threat of Nelson, Haggard and Price.

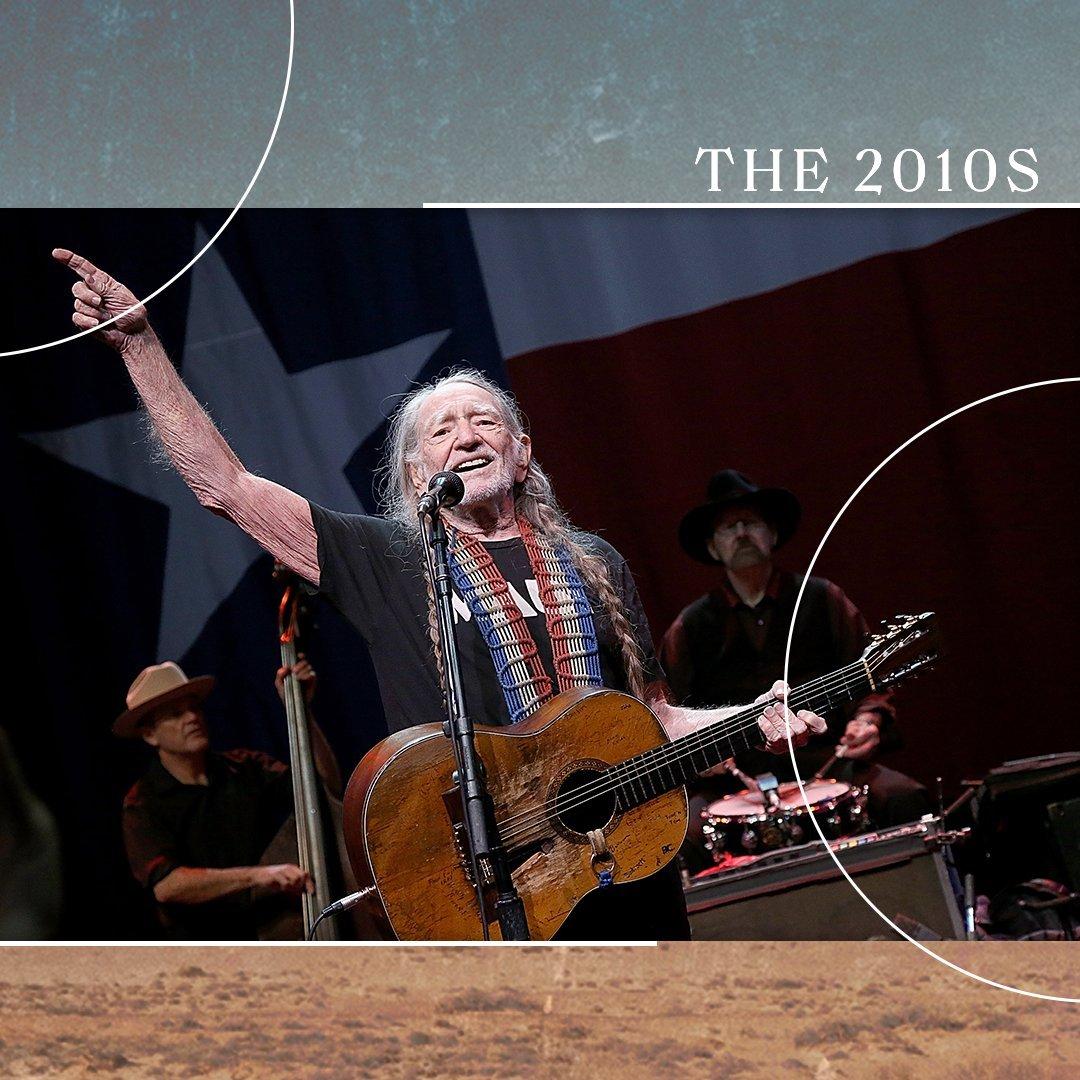

The 2010s

*Willie Nelson performs on New Year's Eve at ACL Live in 2014 in Austin, Texas | Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images*

Nelson was consistent and prolific throughout the 2010s. If you're a fan or just curious, you can conceivably drop into almost any album — from 2012's Heroes to 2014's Band of Brothers to 2018's Last Man Standing — and walk away smiling.

That said, a few stand out from the pack. Django and Jimmie, which marks Nelson and Haggard's sixth and final collaborative album, is by turns touching ("Somewhere Between") and uproarious (the irresistible stoner boogie "It's All Going to Pot").

What's more, Django and Jimmie is a glorious penultimate dispatch from the very missed Haggard, who died in 2016. Nelson touchingly paid tribute to his fallen friend on "He Won't Ever Be Gone," from 2017's excellent God's Problem Child.

Finish off your exploration of 2010s Nelson with 2018's My Way, a tribute to Frank Sinatra, and 2020's spare-yet-satisfying Ride Me Back Home.

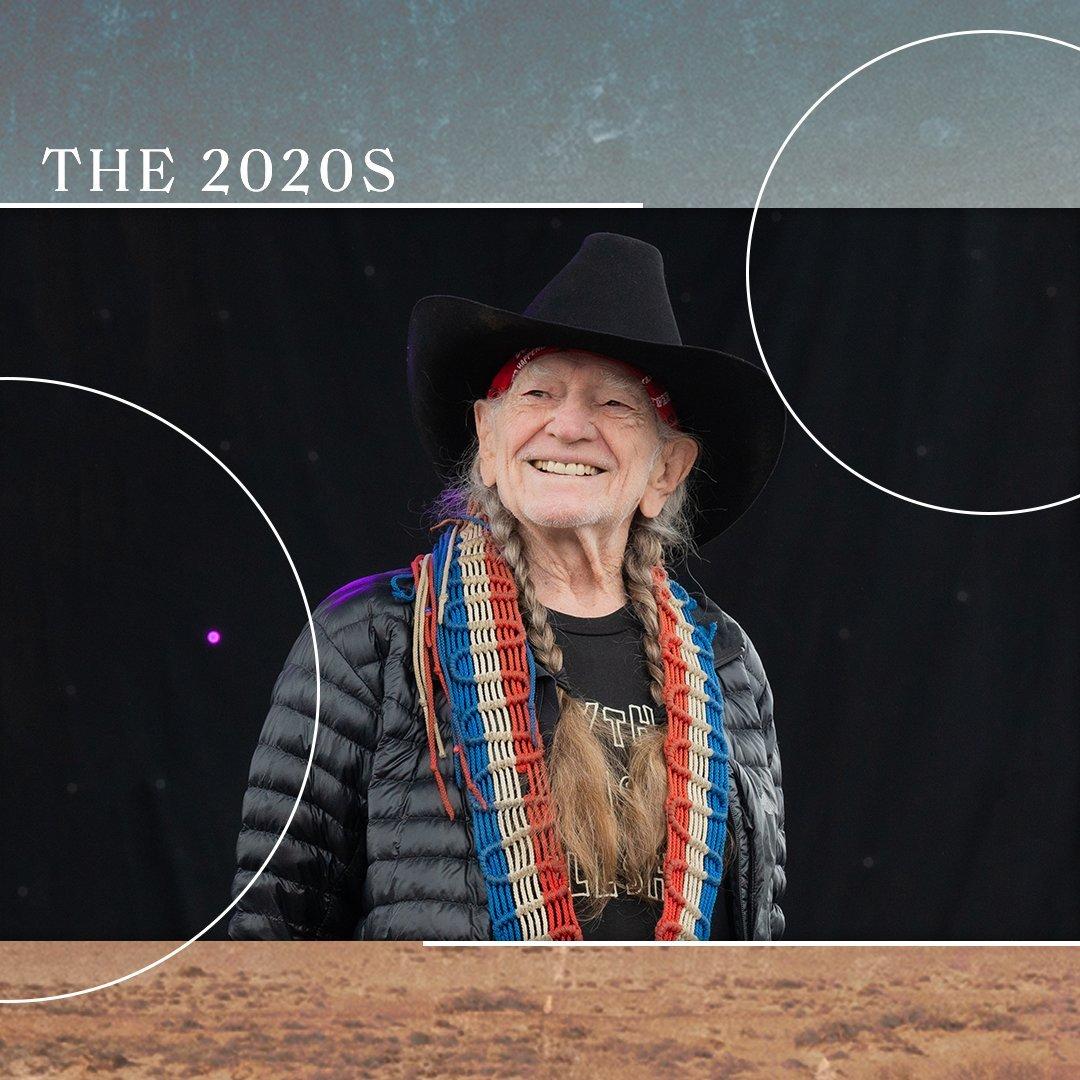

The 2020s

*Willie Nelson performs at the Luck Reunion in 2022 in Luck, Texas | Photo: Jim Bennett/WireImage*

By all available evidence, Nelson is firing on all cylinders in the 2020s. He entered the new decade with 2020's tender First Rose of Spring. Nelson followed that up almost immediately with 2021's That's Life, another excellent tribute to Sinatra.

That year's The Willie Nelson Family reflected his eternal bond with his biological and musical family — Nelsons Amy, Bobbie, Lukas, Micah and Paula. And on April 29, Nelson gave us A Beautiful Time, a gorgeous collection of originals and covers, with an especially touching title track written by Shawn Camp.

"If I ever get home/ I'll still love the road/ Still love the way that it winds," Nelson sings therein. "Now when the last song's been played/ I'll look back and say/ I sure had a beautiful time."

The song carries a tinge of finality, and on the cover, Nelson strolls into the sunset. Does it signal that Nelson is finally winding down? It'd be presumptuous to say so, even though he's numberless albums deep and will turn 90 in 2023.

Despite recent health issues, Nelson is magically, gratefully still on the road. He sings as well, or better, than ever. And his guitar playing alone remains an idiosyncratic force — to say nothing of his still-intact songwriting and interpreting talents.

For all his travails and triumphs, Nelson has remained creatively vital and deeply himself throughout his astonishing career and into his seventh active decade — partly because of his family’s support, partly for staying uncompromising, but also because he never let the old man in.

Photo: Marcelo Hernandez/Getty Images

feature

The Environmental Impact Of Touring: How Scientists, Musicians & Nonprofits Are Trying To Shrink Concerts' Carbon Footprint

"It’s not just [about] a single tour, it’s every tour," singer Brittany Howard says of efforts to make concerts more sustainable. From the nonprofit that partnered with Billie Eilish, to an MIT initiative, the music industry aims to curb climate change.

Beloved by fans around the globe, yet increasingly unaffordable for many artists, concert tours are central to the world of entertainment and local economies. After the pandemic-era global shuttering of concert venues large and small, tours are back, and bigger than ever.

Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is smashing records, selling more than four million tickets and earning more than $1 billion. But that tour made headlines for another reason: as reported in Business Insider and other outlets, for a six-month period in 2023, Swift’s two jets spent a combined 166 hours in the air between concerts, shuttling at most a total of 28 passengers.

Against that backdrop, heightened concerns about the global environmental cost of concert touring have led a number of prominent artists to launch initiatives. Those efforts seek both to mitigate the negative effects of touring and communicate messages about sustainability to concertgoers.

A 2023 study sponsored by Texas-based electricity provider Payless Power found that the carbon footprint of many touring bands was massive. In 2022, concert tours in five genres — country, classic rock, hip-hop/rap, metal and pop — were responsible for CO2 emissions totaling nearly 45,000 metric tons. A so-called greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide contributes to climate change by radiative forcing; increased levels of CO2 also contribute to health problems.

No serious discussion of climate issues suggests a worldwide halt to live music touring, but there exists much room for improvement. Both on their own and with the help of dedicated nonprofit organizations, many artists are taking positive steps toward mitigating the deleterious effects that touring exerts upon the environment.

Smart tour planning is one way to lessen an artist’s carbon footprint. Ed Sheeran’s 2022 European run minimized flights between concert venues, making that leg of his tour the year's most environmentally efficient. Total carbon dioxide emissions (from flights and driving) on Sheeran’s tour came to less than 150 metric tons. In contrast, Dua Lipa’s tour during the same period generated 12 times as much — more than 1800 metric tons — of CO2.

In July, singer/songwriter and four-time GRAMMY nominee Jewel will embark on her first major tour in several years, alongside GRAMMY winner Melissa Etheridge. During the planning stage for the 28-city tour, Jewel suggested an idea that could reduce the tour’s carbon footprint.

"I always thought it was so silly and so wasteful — and so carbon footprint-negative — to have separate trucks, separate lighting, separate crews, separate hotel rooms, separate costs," Jewel says. She pitched the idea of sharing a backing band with Etheridge. "I’ve been trying to do this for 25 years," Jewel says with a laugh. "Melissa is the first person who took me up on it!"

The changes will not only reduce the tour’s carbon footprint, but they’ll also lessen the cost of taking the shows on the road. Acknowledging that there are many opportunities to meet the challenges of touring’s negative impact upon the environment, Jewel emphasizes that “you have to find [solutions] that work for you.”

Sheeran and Jewel aren’t the only popular artists trying to make a difference. A number of high profile artists have become actively involved in creating the momentum for positive change. Those artists believe that their work on sustainability issues goes hand in hand with their role as public figures. Their efforts take two primary forms: making changes themselves, andadvocating for action among their fans.

The Climate Machine

Norhan Bayomi is an Egypt-born environmental scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a key member of the Environmental Solutions Initiative, a program launched to address sustainable climate action. She’s also a recording artist in the trance genre, working under the name Nourey.

The ESI collaborates with industry heavyweights Live Nation, Warner Music Group and others as well with touring/recording acts like Coldplay to examine the carbon footprint of the music industry. A key component of the ESI is the Climate Machine, a collaborative research group that seeks to help the live music industry reduce carbon emissions. "As a research institution, we bring technologies and analytics to understand, in the best way possible, the actual impact of the music industry upon climate change," says John Fernández, Director of the ESI.

"I’m very interested in exploring ways that we can bridge between environmental science, climate change and music fans," Bayomi says. She explains that the tools at the ESI’s disposal include "virtual reality, augmented reality and generative AI," media forms that can communicate messages to music fans and concertgoers. Fernández says that those endeavors are aimed at "enlisting, enabling and inspiring people to get engaged in climate change."

The Environmental Solutions Initiative cites Coldplay as a high-profile success. The band and its management issued an "Emissions Update" document in June 2024, outlining its success at achieving their goal of reducing direct carbon emissions from show production, freight, band and crew travel. The established target was a 50 percent cut in emissions compared to Coldplay’s previous tour; the final result was a 59 percent reduction between their 2022-23 tour and 2016-17 tour.

A significant part of that reduction came as a result of a renewable-energy based battery system that powers audio and lights. The emissions data in the update was reviewed and independently validated by MIT’s Fernández.

Change Is Reverberating

Guitarist Adam Gardner is a founding member of Massachusetts-based indie rockers Guster, but he's more than just a singer in a rock band. Gardner is also the co-founder of REVERB, one of the organizations at the forefront of developing and implementing climate-focused sustainability initiatives.

Founded in 2004 by Gardner and his wife, environmental activist Lauren Sullivan, REVERB began with a goal of making touring more sustainable; over the years its focus has expanded to promote industry-wide changes. Today, the organization promotes sustainability throughout the industry in partnership with music artists, concert venues and festivals.

REVERB initiatives have included efforts to eliminate single-use plastics at the California Roots Music & Arts Festival, clean energy projects in cooperation with Willie Nelson and Billie Eilish, and efforts with other major artists. Gardner has seen sustainability efforts grow over two decades

"It’s really amazing to see the [change] with artists, with venues, with fans," Gardner says. "Today, people are not just giving lip service to sustainable efforts; they really want to do things that are real and measurable."

The Music Decarbonization Project is one tangible example of REVERB’s successes. "Diesel power is one of the dirtiest sources of power," Gardner explains. "And it’s an industry standard to power festival stages with diesel generators." Working with Willie Nelson, the organization helped switch the power sources at his annual Luck Reunion to clean energy. At last year’s festival, Nelson’s headlining stage drew 100 percent of its power from solar-powered batteries. "We set up a temporary solar farm," Gardner says, "and the main stage didn’t have to use any diesel power."

Billie Eilish was another early supporter of the initiative. "She helped us launch the program," Gardner says. Eilish’s set at Lollapallooza 2023 drew power from solar batteries, too.

With such high-profile successes as a backdrop, Gardner believes that REVERB is poised to do even more to foster sustainable concerts and touring. "Our role now," he says, "isn’t just, ‘Hey, think about this stuff.’ It’s more how do we push farther, faster?"

Adam Gardner believes that musicians are uniquely positioned to help make a difference where issues of sustainability are concerned. "When you’re a musician, you’re connecting with fans heart-to-heart. That’s what moves people. And that’s where the good stuff happens."

Small-scale, individual changes can make a difference — especially when they’re coordinated and amplified among other concertgoers. Gardner provides real-world examples. "Instead of buying a plastic bottle, I brought my reusable and filled it up. Maybe I carpooled to the show." Conceding that such steps might seem like drops of water in a giant pool, he emphasizes the power of scale. "When you actually multiply [those things for] just one summer tour, it adds up," he says. "And it reminds people, ‘You’re not alone in this; you’re part of a community that’s taking action."

Gardner understands that REVERB’s arguments have to be framed the right way to reach concertgoers. "Look," he admits, "It’s a concert. We’re not here to be a buzzkill. Our [aim] now is making sure people don’t lose hope." He says that REVERB and its partners seek to demonstrate that, with collective action and cultural change, there is reason for optimism.

"There’s a wonderful feedback loop between hope and action," Gardner says with a smile. "You can’t really have one without the other."

Sustainable Partnerships

Tanner Watt is Director of Partnerships at REVERB; he works directly with touring artists to develop, coordinate and implement initiatives that bring together his organization’s objectives and the specific personal concerns of the artists. "I get to come up with all the fun, big ideas," he says with a wide smile.

Watt acknowledges that like every concertgoer, each touring artist has a certain level of responsibility where sustainability is concerned. "And everyone can be doing something," he says, noting a number of straightforward actions that artists can put in place while on tour. "They can eliminate single-use waste. They can donate hotel toiletries that [would otherwise] hit the landfill."

Watt stresses that artists can lead by example. "Nobody wants to listen to an artist telling them what to do if they’re not doing it themselves," he says. "But we believe that everybody cares about something." He suggests that if an artist has cultivated a following, "Why not use [that platform] to be that change you want to see in the world?"

Each artist has his or her own specific areas of concern, but Watt says that there’s a base level of "greening" that takes place on every REVERB-affiliated tour. Where things go from there is up to the artist, in coordination with REVERB. Watt mentions Billie Eilish and her tour’s sustainability commitment. "The Venn diagram of food security, community health, access to healthy food, and the impact on the planet is a big cause for her," he says. "So there’s plant-based catering for her entire crew, across the entire tour."

Speaking to Billboard, Eilish's mother Maggie Baird said championing sustainability starts with artists. "If artists are interested, it does really start with them telling their teams that they care and that it’s foremost in their thoughts." In the same conversation, Eilish called the battle for sustainability "a never-ending f–king fight."

Watt acknowledges that with so many challenges, it’s important for a concerned artist to focus on the issues that move them the most, and where they can make the biggest difference. "Jack Johnson is a great example," he says. While Johnson is a vocal advocate for many environmental issues, on tour he focuses on two (in Watt’s words) "cause umbrellas": single-use plastics solutions and sustainable community food systems. Each show on the tour hosts tables representing local nonprofit organizations, presenting concertgoers with real-world, human-scale solutions to those specific challenges.

Four-time GRAMMY winner Brittany Howard is another passionate REVERB partner. "Knowing that I wanted to make my tours more sustainable was a start," she tells GRAMMY.com, "but working with REVERB really helped me bring it to life on the road. REVERB has helped us with guidelines and a green rider to keep our stage, greenrooms and buses more sustainable."

After listing several other specific ways that her tour supports sustainability, Howard notes, "By supporting these efforts, I am helping ensure future generations have access to clean water, fish, and all that I love about the outdoors." A dollar from every ticket sold to a Brittany Howard concert goes toward support of REVERB’s Music Decarbonization project. "I’m also excited to see industry-wide efforts that are reducing the carbon pollution of live music," Howard continues. "Because it’s not just [about] a single tour, it’s every tour."

There’s a popular aphorism: "You can’t manage what you can’t measure." From its start, REVERB has sought not only to promote change, but to measure its success. "As long as I’ve been at REVERB, we’ve issued impact reports," says Tanner Watt. "We include data points, and give the report to the artists so they understand what we’ve done together." He admits that some successes are more tangible than others, but that it’s helpful to focus on the ones that can be quantified. "We’re very excited that our artists share those with their fans."

Watt is clear-eyed at the challenges that remain. "Even the word ‘sustainable’ can be misleading," he concedes, suggesting that the only truly sustainable tour is the one that doesn’t happen. "But if folks don’t step it up and change the way we do business in every industry — not just ours — we’re going to get to a place where we’re forced to make sacrifices that aren’t painless." Getting that message across is REVERB’s aim. "We can’t stop the world," Watt says. "So we find ways to approach these things positively."

Watt says that the fans at concerts featuring Jack Johnson and the Dave Matthews Band — both longtime REVERB partners — are already on board with many of the sustainability-focused initiatives which those artists promote. "But there are lots of artists — and lots of fan bases — out there that aren’t messaged to, or have been mis-messaged to," he says. "I’m really excited to find more ways to expand our reach to them, beyond mainstream pop music. Because these are conversations that are meaningful for everyone, regardless of political affiliation or other beliefs."

Reimagining The Planet’s Future

Singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Adam Met does more than front AJR, the indie pop trio he founded in 2005 with brothers Jack and Ryan. Met has a PhD in sustainable development and is a climate activist; he's also the founder/Executive Director of Planet Reimagined, a nonprofit that promotes sustainability and activism through its work with businesses, other organizations and musicians.

"I’ve spent years traveling around the world, seeing the direct impact of climate change," Met says. He cites two recent and stark examples. "When we pulled up to a venue in San Francisco, the band had to wear gas masks going from the bus into the venue, because of forest fires," he says. AJR’s road crew had to contend with a flash flood in Athens, Greece that washed out their hotel. "And in Rome, some of our crew members fainted because of the heat."

Encouraged by representatives from the United Nations, Met launched Planet Reimagined. Met’s approach focuses on tailored, city-specific actions to empower fans and amplify diverse voices in the climate movement. Through social media and live shows, Met strives to galvanize climate activism among AJR fans. And the methods he has developed can be implemented by other touring artists.

Met points out that one of the most climate-unfriendly parts of the entire concert tour enterprise is fans traveling to and from the concerts. And that’s something over which the artist has little or no control. What they can do, he says, is try to educate and influence. Working closely with Ticketmaster and other stakeholders, Met’s nonprofit initiated a study — conducted from July to December 2023, with results published in April 2024 — to explore the energy that happens at concerts. "In sociology," he explains, "that energy is called collective effervescence." The study’s goal is to find ways to channel that energy toward advocacy and action.

Polling a quarter million concertgoers across musical genres, the study collected data on attitudes about climate change. "Seventy-three percent of fans who attend concerts believe that climate change is real, and that we need to be doing more about it," Met says. "Seventy-eight percent have already taken some sort of action in their lives." He believes that if his organization can activate even a fraction of the estimated 250 million people annually who attend concerts around the globe, "that’s the ballgame."

Met’s goal is to do more than, say, get concertgoers to switch from plastic to paper drinking straws. "At scale those things make a difference. But people want to see actions where there’s a track record," he says; a return on investment.

AJR will be putting a plan into action on the second half of their upcoming arena tour. Part of the initiative is encouraging concertgoers to register to vote, and then actually vote. Beyond that, Met has specific actions in mind. "At every single stop, we’re putting together materials around specific policies that are being debated at the local level," he explains. "We give people a script right there, so they can call their elected representative and say, ‘I want you to vote [a certain way on this issue].’"

He believes the initiative will lead to thousands of people contacting – and hopefully influencing – their representatives. With regard to sustainability issues, Met is convinced that "the most impact that you can have as an artist is when you give fans ways to pick up the mantle themselves."

Artists Who Are Going On Tour In 2024: The Rolling Stones, Drake, Olivia Rodrigo & More

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic via Getty Images

list

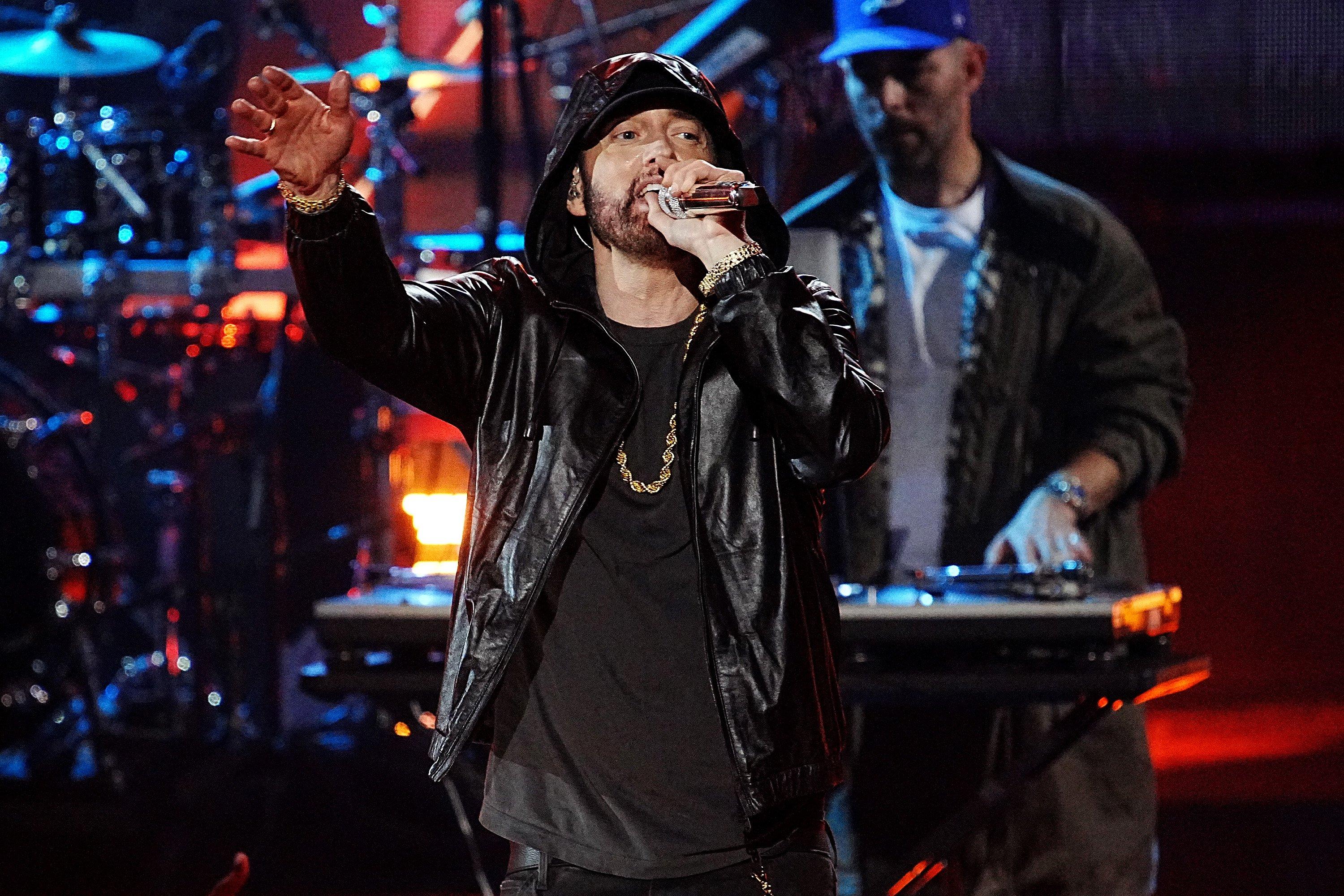

New Music Friday: Listen To New Albums & Songs From Eminem, Maya Hawke, ATEEZ & More

Dive into the weekend with music that’ll make you dance, brood and think — by Jessie Reyez, Ayra Starr, Adam Lambert, and many more.

After the cookouts and kickbacks of Memorial Day weekend, getting through the workweek is never easy. But you made it through — and now it's time for another weekend of however you decompress. As always, killer jams and musical food for thought have arrived down the pipeline.

As you freshen up your late-spring playlist, don't miss these offerings by artists across generations, moods, genres, and vibes — from K-pop to classic country and beyond.

Eminem — "Houdini"

It looks like Dua Lipa isn't the only artist to name-drop Erik Weisz this year. In a recent Instagram video with magician David Blaine, Eminem hinted at a major career move, quipping, "For my last trick, I'm going to make my career disappear," as Blaine casually noshed on a broken wineglass.

With Em's next album titled The Death of Slim Shady, fans were left in a frenzy — was he putting the mic down for good? If "Houdini" is in fact part of Eminem's final act, it seems he'll be paying homage to his career along the way: the song includes snippets of Em classics "Without Me," "The Real Slim Shady," "Just Lose It" and "My Name Is."

The superhero comic-themed video also calls back to some of the rapper's iconic moments, including the "Without Me" visual and his 2000 MTV Video Music Awards performance. It also features cameos from the likes of Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, 50 Cent, and Pete Davidson — making for a star-studded thrill ride of a beginning to what may be his end.

Read More: Is Eminem's “Stan” Based On A True Story? 10 Facts You Didn't Know About The GRAMMY-Winning Rapper

Maya Hawke — 'Chaos Angel'

"What the Chaos Angel is to me," Maya Hawke explained in a recent Instagram video, "is an angel that was raised in heaven to believe they're the angel of love, then sent down to do loving duties."

Chaos Angel, the third album by Maya Hawke, out via Mom+Pop Records, is an alt-rock treasure with a psychologically penetrating bent. Smoldering tracks like "Dark" and "Missing Out" plumb themes of betrayal and bedlam masterfully.

Jessie Reyez & Big Sean — "Shut Up"

Before May 31, Jessie Reyez's 2024 releases have come in the form of airy contributions for Bob Marley: One Love and Rebel Moon. And for the first release of her own, she's bringing the heat.

Teaming up with fellow rapper Big Sean for "Shut Up," Reyez delivers some fiery lines on the thumping track: "They b—es plastic, that b— is a catfish, oh-so dramatic/ And I'm sittin' pretty with my little-ass t—es winnin' pageants." Big Sean throws down, too: "B—, better read the room like you telepromptin'/ And watch how you speak to a n—a 'cause I'm not them."

Foster the People — "Lost In Space"

Indie dance-pop favorites Foster The People — yes, of the once-inescapable "Pumped Up Kicks" fame — are back with their first new music since 2017's Sacred Hearts Club. The teaser for their future-forward, disco-powered new song, "Lost in Space," brings a psychedelic riot of colors to your eyeballs.

The song is equally as trippy. Over a swirling, disco-tinged techno beat, the group bring their signature echoing vocals to the funky track, which feels like the soundtrack to an '80s adventure flick.

"Lost in Space" is the first taste of Foster The People's forthcoming fourth studio album, Paradise State of Mind, which will arrive Aug. 16. If the lead single is any indication — along with frontman Mark Foster's tease that the album started "as a case study of the late Seventies crossover between disco, funk, gospel, jazz, and all those sounds" — fans are in for quite the psychedelic ride.

Arooj Aftab — 'Night Reign'

Arooj Aftab landed on the scene with the exquisitely blue Vulture Prince, which bridged modern jazz and folk idioms with what she calls "heritage material" from Pakistan and South Asia. The album's pandemic-era success threatened to box her in, though; Aftab is a funny, well-rounded cat who's crazy about pop music, too. Crucially, the guest-stuffed Night Reign shows many more sides of this GRAMMY-winning artist — her sound is still instantly recognizable, but has a more iridescent tint — a well-roundedness. By the strength of songs like "Raat Ki Rani" and "Whiskey," and the patina of guests like Moor Mother and Vijay Iyer, this Reign is for the long haul.

Learn More: Arooj Aftab, Vijay Iyer & Shahzad Ismaily On New Album Love In Exile, Improvisation Versus Co-Construction And The Primacy Of The Pulse

Willie Nelson — 'The Border'

By some counts, Willie Nelson has released more than 150 albums — try and let that soak in. The Red Headed Stranger tends to crank out a Buddy Cannon-produced album or two per year in his autumn years, each with a slight conceptual tilt: bluegrass, family matters, tributes to Harlan Howard or the Great American Songbook. Earthy, muted The Border is another helping of the good stuff — this time homing in on songwriters like Rodney Crowell ("The Border"), Shawn Camp ("Made in Texas") and Mike Reid ("Nobody Knows Me Like You.") Elsewhere, Nelson-Cannon originals like "What If I'm Out of My Mind" and "How Much Does It Cost" fold it all into the 12-time GRAMMY winner's manifold musical universe.

ATEEZ — 'GOLDEN HOUR : Part.1'

South Korean boy band ATEEZ last released new material with late 2023's The World EP.Fin: Will. Now, they're bringing the K-pop fire once again with their 10th mini-album, GOLDEN HOUR Part.1.

Released in a rainbow of physical editions, the release was teased by a short clip for "WORK," where ATEEZ pans for gold like old prospectors in an off-kilter desert scene, then proceeds to throw the mother of all parties. As for the rest of GOLDEN HOUR, they bring flavors of reggaeton ("Blind), wavy R&B ("Empty Box") and reggae ("Shaboom") — further displaying their versatility as a group, and setting an exciting stage for Part.2.

Learn More: Inside The GRAMMY Museum's ATEEZ & Xikers Pop-Up: 5 Things We Learned

Ayra Starr — 'The Year I Turned 21'

Beninese-Nigerian singer and GRAMMY nominee for Best African Music Performance Ayra Starr pays homage to the big two-one with her second album, The Year I Turned 21, which she's been teasing all month. We've seen the crimson, windswept cover art; we've soaked up the 14 track titles, which reveal collaborations with the likes of ASAKE, Anitta, Coco Jones, and Giveon. Now, after small tastes in singles "Commas,""Rhythm & Blues" and "Santa" (with Rvssian and Rauw Alejandro), we can behold what the "Rush" star has called "excellent, sonically amazing" and "unique, because I've been evolving sonically."

Watch: Ayra Starr’s Most Essential “Item” On The Road Is Her Brother | Herbal Tea & White Sofas

Adam Lambert — "LUBE" & "WET DREAM"

The "American Idol" and Queen + Adam Lambert star is turning heads — for very good reason. He's going to release AFTERS, a new EP of house music and an unflinching exploration of queerness and sex-positivity. "I throw many house parties and my aim was to create a soundtrack inspired by wild nights, giving a voice to our communities' hedonistic desires and exploits," Lambert explained in a press release.

The first two singles, "LUBE" and "WET DREAM," achieve exactly that. From the pulsing beat of "LUBE" (along with the "Move your body like I do" demand of the chorus) to the racing melody of "WET DREAM," it's clear AFTERS will bring listeners straight to a sweaty dance floor — right where Lambert wants them.

Wallows Talk New Album Model, "Entering Uncharted Territory" With World Tour & That Unexpected Sabrina Carpenter Cover

Photo: Christopher Morley

interview

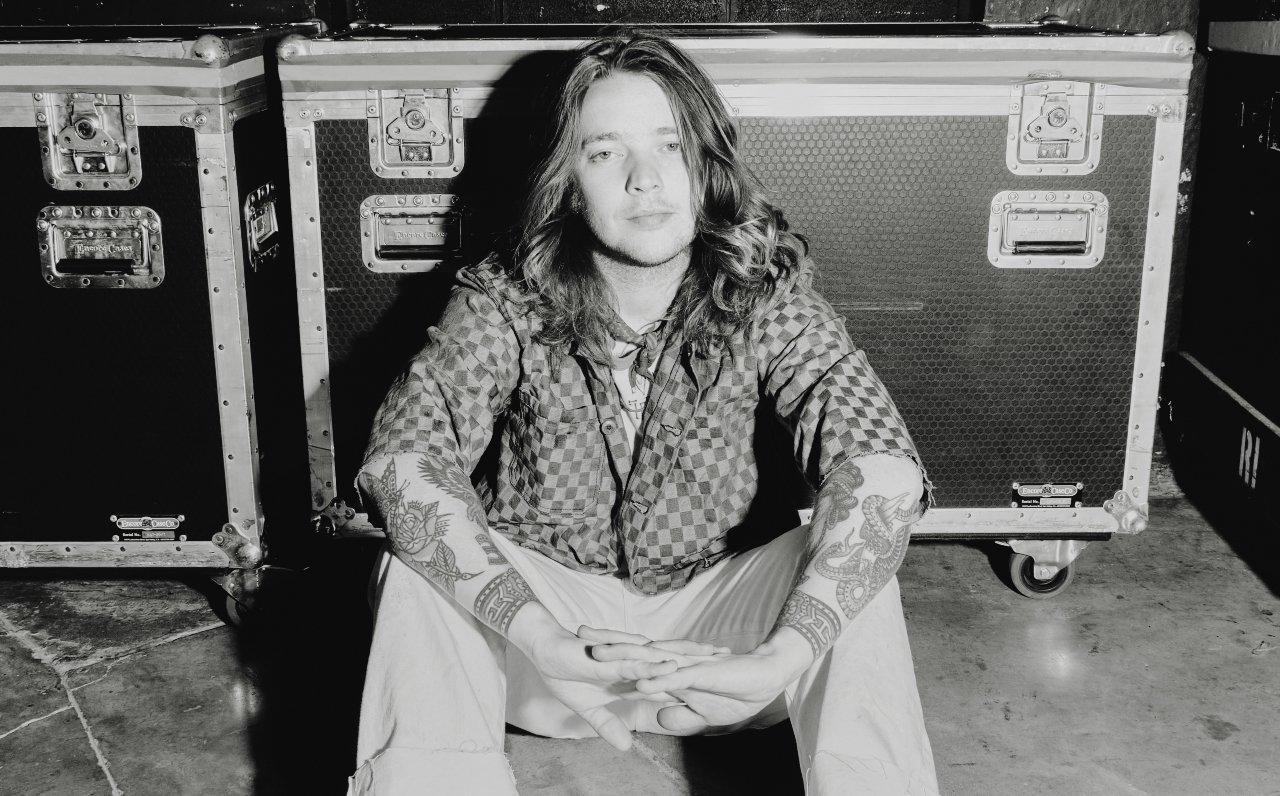

Billy Strings On His Three GRAMMY Nominations, Working With Dierks Bentley & Willie Nelson

When Willie Nelson asked Billy Strings for instructions in the studio, he thought, 'I'm nobody, dude; you're Willie Nelson. You're asking me?' But Strings is certainly somebody: he's up for three golden gramophones at the 2024 GRAMMYs.

Is it possible to write someone else's song for them? Which isn't the same as being an outside writer: it's writing something that spiritually belongs to your influence. That's the sensation that came over guitar and banjo picker Billy Strings, when he wrote "California Sober."

"California Sober" had the lilt and thematic ring of something like Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard's 1983 hit "Reasons to Quit"; in fact, it felt like it emanated from Nelson entirely. Which makes sense, given that Strings had just hit the road with the country patriarch.

"I don't think I would've recorded the song if Willie wouldn't have wanted to do it with me," Strings tells GRAMMY.com. "It's like, I'm not even going to cut this unless Willie wants to do it. It would just be like ripping off Willie's sound."

Exhilaratingly, the Red-Headed Stranger accepted — and their resultant duet of "California Sober" is nominated for Best American Roots Song at the 2024 GRAMMYs. And that's just the beginning of his prospects at Music's Biggest Night, coming up on Feb. 4.

At the 2024 GRAMMYs, Strings also picked up a nomination for Best Bluegrass Album for Me/And/Dad — his album with his bluegrass old-timer father, Terry Barber. And Dierks Bentley's "High Note," featuring Strings, is up for Best Country Duo/Group Performance.

Read on for an interview with Strings about how these albums and songs came to be, and what he learns from Nelson, Bentley, and Béla Fleck, and much more.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about your relationship with the Recording Academy, and the GRAMMYs.

Well, the last few years, let's see: we were nominated for Best Bluegrass Album for Home, and we won that [in 2021]. And the next year we were nominated for two different things. Can't really remember, but we didn't win anything. [Editor's note: Strings received nominations for Best Bluegrass Album (Renewal) and Best American Roots Performance ("Love And Regret").]

That was when I went out there and checked it out, and had a great time being on the red carpet and seeing all the crazy outfits and stuff. And it's kind of crazy because although we didn't win, my friend Béla Fleck won.

I played on [his] record [2021's My Bluegrass Heart]. I was so honored to play with Béla Fleck and all those amazing musicians on that record, and it's been like 20 years since Bela made a bluegrass record — it's like, man, he deserves it.

And that was a big moment in my life — being in the studio with those guys, making that record. I still look back and I'm grateful to Béla for giving me the opportunity to do that because it gave me so much more confidence in myself. I still get almost emotional when I think about Béla actually asking me to be on his record because it just means so much to me. It's just always been kind of crazy. I'm just completely flabbergasted and honored because I never thought I'd be nominated for a GRAMMY or anything — let alone we won one already.

[Me/And/Dad] is probably the most important record I'll ever make because it's with my dad. And I think it's an important record for bluegrass too, just because of the songs and kind of the way we played those songs. And there's an old style that, as time goes on, the guys who sing and play like that are kind of dying off.

My dad's one of that older guard, and he just has this beautiful voice and amazing guitar playing, and he taught me everything I know about bluegrass music and it's deep in my heart and soul. It was so cool to be able to call my dad and say, hey man, guess what? Our record got nominated for a GRAMMY," and he's like, "Holy s—."

Can you drill deeper into why it's the most important thing you'll ever make?

Because everything I know about music, and bluegrass, I learned from my dad.

He started me off really young in my childhood; it was so based around the music. All the sweet memories that I have from when I was a boy were based around bluegrass music, and it seeps into your heart and soul and gets under your skin in a way that I guess only bluegrassers could really know.

It's music that can make me cry and make me laugh, and it gives me déjà vu, and it's almost a portal directly to my childhood back before I knew anything dirty about the earth. It was back, simpler times, just hanging around the campfire, picking music, and with my family and just beautiful times.

And whenever I get together with my dad and play, it brings me back to just being a little boy.

And can you speak more to the importance of Béla Fleck? I interviewed him at Newport Folk, and he couldn't have been kinder nor gentler, with a fraction of the ego he could rightfully have.

He's the best man. He's become a good friend of mine. Obviously, he was my hero first. And so that's always good when you meet your heroes and they're really cool people. It means a lot.

And he's just like any of us; he's constantly just playing and trying to write and get better. He said to me one time, "We're all just trying to keep our heads above water," 'cause maybe I was feeling down about my playing or whatever, he's like, man, we're all doing the same thing.

What he's done for new acoustic music is incredible. The things that he's done with the five string banjo, and not only him, but his bands like the Flecktones and New Grass Revival with Sam Bush and John Cowan and those guys just, that's a big inspiration to us up and comers that are playing bluegrass music but like a little bit more progressive side.

I listen to everything from heavy metal to hip-hop and jazz and everything, so it's kind of sweet when you can take bluegrass instruments and play any kind of fusion music. And Béla is a huge innovator in that world.

One thing he told me was, "There is no best." I'm sure that resonates with you in some way.

Yeah, absolutely. Everybody's kind of the best at what they do. I'll never be as good as Tony Rice, ever — not if I practice eight hours a day for the rest of my life. I'll never touch him. But if I just kind of focus on what I'm doing and try to invent my own voice, maybe I'll be the best one at that.

How would you characterize that voice you've developed?

Well, I was raised playing bluegrass music — pretty traditional bluegrass. And then in my teenage years, I veered off and played heavy metal and got into more writing songs and just lots of different music other than bluegrass.

But when I came back to bluegrass, some of those things kind of stuck, particularly the stage performance thing. A lot of bluegrass bands, I feel like just stand there and play, 'cause they don't really have to do anything else. I can't help but move around and jump around and bang my head and stuff like I used to in a heavy metal band, 'cause that's how I learned to perform.

I've seen people be like, man, this is not headbanging music. And I'm like, "Well, hell yeah, it is."

Can you talk about Dierks Bentley, and "High Note," and the road to the nomination for Best Country Duo/Group Performance?

Dierks is a good buddy. He's just a real dude. I met him a few years ago. I was walking down the street, I was going to lunch with [flatpicker] Bryan Sutton and this white pickup truck pulled up, and Brian's like, "Oh, hey, what's up, man?"

We started talking. I didn't even know who it was. And the inside of his pickup truck was a mess. It was just like, s— everywhere, tapes and old, just like my car. So I'm like, okay, well, who's this guy? And then I realized he's a big country star, and I liked that he was a big country star and drove around with a messy truck.

Are you a messy truck guy too?

I try to keep it pretty nice nowadays, but yeah, usually my s— gets trashed. There's like fishing lures and just bulls— everywhere.

So I don't know, that made an impression on me for some reason — the inside of the cab of his truck. But after that, we became buddies and we had picked a couple times. He's a good buddy of [mandolinist] Sam Bush as well and so that's kind of a mutual friend of ours.

And there had been a couple times on stage where me and Sam were playing with Dierks, and he can play some bluegrass, man. He knows a lot of bluegrass songs and stuff.

So when he hit me up to do this song with him, I was like, of course, but especially when I heard it on a high note, he knows I like to smoke a lot of weed and stuff, so it was kind of like the perfect song for me. And it had that bluegrass flavor so I could jump on guitar and sing the tenors and stuff, sing the harmonies and stuff.

How popular is weed in the bluegrass community?

Well, I mean, in our scene it's pretty popular, but there's also folks that don't like to see me up there smoking or anything… maybe the more old-school kind of conservative types. But I just do my thing, man. I'm not trying to hurt nobody.

Speaking of, we have "California Sober" with Willie Nelson.

Man, so, Willie Nelson, holy f—.

Yeah, dude.

Wow, I love him so much. My grandpa loved him a lot, and my mom. When I grew up, my dad would, he'd be singing "Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain" and all them songs, and a lot of songs off Red Headed Stranger, I heard growing up — my dad singing those, and my grandpa playing the records, and stuff.

Willie was a big deal, especially to my grandpa, and he's been dead since 2001. So I always think about my grandpa when I think of Willie too, 'cause he loved him so much. If my grandpa was around to hear this song, he would just lose it.

And the way that it came about was, I went on tour with Willie on his road show, The Outlaw Tour, and we were one of the bands on there. And during that tour, Willie invited me up on his bus, and we hung out for a little while and just shot the s— and told jokes, and he told me how he got Trigger and everything, and talked about Django Reinhardt and Doc Watson.

I just had a great time. It was like hanging out with my grandpa or something, and I had a great time on the tour. And when I got home from that tour, I was sitting out by my burn pile and I ripped off this piece of cardboard, and I just had this tune going in my head, "I'm California sober, as they say / Lately, I can't find no other way."

I just wrote it down on this piece of cardboard. And then I went inside and kind of started writing a song — and I realized that I was writing a Willie Nelson song. I was so inspired by being on the road with Willie that I came home and I wrote this song — it's like I wrote it, but it was such a Willie song.

So what happened next?

I had my manager reach out to his manager, or whatever, and say, "Hey, here's this song that I wrote. Would you want to do it with me? And the answer was a resounding, 'Hell yes.'"

We made the track here in Nashville with me and the band, and then I went down to Luck, to his studio down there at his home in Texas, and Willie came in and we just hung out for a while, man. He sat down in front of the mic and he said, "Well, what do you want me to do?" And I was like, What the hell? I'm nobody, dude; you're Willie Nelson. You're asking me?

But he was like, "Well, do you want me to sing a verse?" I was like, "Tell, try to sing harmonies on the chorus and then take a crack at that second verse." So he put the harmonies on the chorus just fine. And when he got to this verse, it seemed like he was kind of just still learning the words a little bit, and I don't know if something [happened] like, he got frustrated on one take or something.

The next time, he just nailed it, and it was like this young Willie voice came out and he just sang so beautifully, and I had goosebumps, and it was just incredible, man.

And then right after that, he finished his part, he said, "We got it?" And I said, "Man, I think we got it. He said, "OK, let's go play cards."

So we went out back to his little spot there, where he's been playing cards for 50 years with everyone, Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson. His old buddy, Steve, [was there]; we were sitting there playing poker, and… I'm sitting there playing cards with two old buddies who have been playing cards together for 50 years, man. Hearing those two talk s— to each other, man.

They took a thousand dollars of my money real quick, and I would've paid another thousand just to sit there at that table and hear them bulls— each other.

What will your call with Willie be like if "California Sober" wins?

I'm going to say, "Hey, man, I'm coming to get my thousand dollars back."

Béla Fleck Has Always Been Told He's The Best. But To Him, There Is No Best.

Photo: Chris Phelps

interview

Jessi Colter's New Album 'Edge Of Forever' Is Timeless In Every Sense Of The Word

On 'Edge of Forever,' the 80-year-old outlaw country star doesn't sound like an elder stateswoman. Her latest could have been released in 1973 or 2013.

As one of the lone women in the outlaw country milieu, Jessi Colter has navigated the music industry with grace for more than half a century — through false starts, lulls, and the death of her husband and collaborator, Waylon Jennings.

But while some living legends can feel a touch frozen in time, Colter is constantly in motion.

"We've just returned home a few days before the Hall of Fame performance, and my house is a wreck," she reports to GRAMMY.com, upon landing back in her Arizona climes. During a brief conversation, she's speed-eating lunch and jumping in a car; she even suspects this interviewer was multitasking as well. ("Are you doing dishes?" Colter inquires, in response to an errant clank over the line.)

That consistent movement — of body, of creative practice — allowed Colter to cook up one of her most inspired albums. Edge of Forever — produced by GRAMMY nominee Margo Price, and mixed by Colter's son, three-time GRAMMY winner and five-time nominee Shooter Jennings.

Backed by Price's crack band, tunes like "Standing on the Edge of Forever," "Lost Love Song" and "Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus" crackle with potency — and have all of the impact of her early work, prior to all these spins around the sun.

But this timelessness doesn't mean it's simply retro, or '70s; it moves through time. Edge of Forever couldn't have happened without the lumps she's taken in the country machine, or the jubilations.

Furthermore, it proves that the hitmaker behind "I'm Not Lisa" and "What's Happened to Blue Eyes" back in '75 remains a force — as a feisty, vital country-music matriarch. Below, Colter chats with GRAMMY.com about Edge of Forever, and what's on the other side.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Congrats on the release of Edge of Forever. I think the word "timeless" gets thrown around a little too much, but the description fits here.

I had one fellow, I asked him how old he was. I figured he was 20 or 28 and he was 60. I think it was [for] Variety. When I first talked to him. And he said it just has such a feeling that it takes him back to the '70s, and I wasn't sure what he meant exactly. I just am who I am and that's who I'll always be.

But anyway, he loved it. He said it really felt, for him, comfortable. And I understand what he's saying. There's a whole lot out there that's not so comfortable.

Interesting. What do you hope people take away from your music?

Well, certainly that, and I hope I communicate with feelings they've had. I loved it on "I'm Not Lisa," when the little girls would send me tapes of themselves singing it. I thought I have communicated, because when I write it's very inward of my experience or somebody really close to me and so forth. So that's how it goes.

Take us back to your early conception of Edge of Forever — the spark that lit a flame.

Well, I had songs. And I became acquainted with Margo, and she helped me out on a Facebook flash [giveaway] of my book An Outlaw and a Lady, for Harper Collins, that I wrote with David Ritz.

And this was 2015. She was pregnant with Ramona when we cut this album and she was about to have the baby. So as far as the genesis, it took two or three visits together, and [her husband] Jeremy [Ivey] and she both intimated that they would love to see me do an album.

It was years later that we did it. And we did it quickly and directly, because she was about to have her baby. And so it didn't take the kind of time that I'd taken on other albums, but it's taken time to wind its path to the yellow brick road, which seems to be Appalachia Records, who she'd worked with before.

[Label owner Loney Hutchins is] great to work with, and I've never worked with a small label that worked with other indies. But anyway, they've been terrific. And so we just kind of were drawn to each other. And I had these songs that she reacted to, and then there was a couple others, then one written on the spot.

And so it just happened and now it's taken the legal teams, and the manager — this and that, so forth. Anyway, it's worked out. It worked its way to here.

Can you talk about your dynamic with Margo and Shooter?

Yeah, it's fantastic. It's easy. I've worked with Shooter before on The Passion of the Christ, where he wrote on the spot with me. It was an album that went with The Passion of the Christ; It wasn't a soundtrack.

We wrote a song called "Please Carry Me Home." If you haven't heard it, try it, because we wrote it and he produced it on the spot. Then [my daughter] Jennifer [or Jenni Eddy] and I actually wrote "Secret Place," which is on this album, a number of years ago.

Waylon was still with us, and he heard that song — and he didn't often say just this, but he said, "You've got to do that." And it's just been in my pocket.

Often, artists keep songs that inspire them. They don't use them until the time is right. And so there were a number of songs that I had been holding onto. "Lost Love Song," "Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus." I totally rewrote that spiritual except the bridge.

Anyway, the dynamic was fantastic with Margo, with Shooter, with Jennifer Eddy Jennings, my daughter; her father is Duane Eddy. Waylon was a wonderful father to her. So, it's been a gift; the whole thing has been a gift for me.

Working with Jenni Eddy must have a gift among gifts.

Oh, yes. She's so gifted and a great singer. She just hasn't come into the public yet, but she's working on a number of things.

And Struggle Jennings, my grandson, recorded a great album with her called Spiritual Warfare, where Struggle is rapping. [Jenni] sings, and she wrote the songs, and then he raps. And it's interesting.

I don't know what she'll end up doing. Her voice is much more melodic than mine, and she sings beautifully with me. It would be worth working to her and Jenny Lynn Young accompany me, if and when I perform. It''s magnetic, the whole thing.

As a singer/songwriter myself, even something I wrote a year ago can feel alien to me today. Can you talk about reacquainting yourself with tunes from many years ago?

I understand that, but if you love a song to start with, you'll always love it. And so that's how it went with me.

"Maybe You Should Have Been Listening" was one of Waylon's favorites on my classic albums, and "With or Without You" was something I wrote a number of years back for a girlfriend of mine who went through being stood up by a well-known man right before their wedding.

Little Stevie Van Zandt loved that song: "With or without you/ I'll go on alone… And like Bob Dylan said, if it's not right, it must be wrong." I love that. And if people would remember that. "Angel in the Fire" I wrote some time ago. I love it every time I sing it, with Lisa Kristofferson in mind.

"Lost Love Song" was a song that I held in my pocket to inspire me. It is talking about the prison of love. I never have been able to find who wrote it. He may be living, he may not, because I had this years before Waylon went, which was 2002.

"Hard On Easy Street" was great fun. I did it on an album that I [do not] yet have the right to publish. Never came out. It's a great song. "I Wanna Be With You" is always an upper, and percussionists particularly love that song because it's such a rhythm.

"Standing on the Edge of Forever" was a new song I wrote in the last 10 years [about]a relationship that just won't come together, and that's what that's about. But it's also, as Lenny Kaye edged me on to say, This is it, either or. It's that time you come to and it's enough of whatever it is, get on or get off.

"Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus" — oh, that's one of the great songs of all time. James Cleveland wrote it, but I rewrote it. But I don't find to ever get any income from that.It's just a great song talking about how it is. If you're going to do right, you may be alone.

"Fine Wine", Jennifer wrote that with some accompaniment by Margo, and it's talking about early widowhood. And it was how it was maybe four years ago, even though that was a 16-year mark of loss for me, I had been alone for 16 years when I said I'm open for love.

And as things work out and good things happen, I met my current husband, a rancher, horseman from Wyoming, and took it a few years to kind of get to know each other, but we're having a good time.

With Edge of Forever out in the world, what are you looking forward to in the near future?

Right now, I'm looking forward to a documentary I've been working with [a production team] on for eight years. It's called They Called Us Outlaws. Eric Gaberman, partnering with the [Country Music] Hall of Fame did so much research on our time — and the sentinel turn of music in our generation — that I said yes.

[It's a] film coming with so much fact, and then he brings it into the present. Those that have a mindset more to try to do what they wrote and how they did it. And the "outlaws" was more or less a branding in a time that branding wasn't even known, and it stuck. So, it's been useful to a lot of new artists coming with new sounds.

*Jessi Colter. Photo: Chris Phelps*

You've lived through so many epochs in the music industry, When you look back on your decades in the industry — all the triumphs and losses — what do you think of?

Well, there have certainly been chances. Don Was ran into us at the Crazy Horse in Orange County. He showed up in the dark, and scared me because I didn't know who he was. While Waylon was doing the show, and he just talked a minute and said, "You know what, Jessi? The '70s were so much fun."

There was something about that that was the beginning of a lot, but it was the ending of something. It was a major turn with the University in Austin having been exposed to a lot of rock. So when Waylon and Willie came with their sound there, they reacted more like a rock group — Waylon did not cross boundaries in those days. You didn't do it. The companies wouldn't allow it.

So, it was an amazing procedure that took place and we were so glad to be part of it. Since then, it's kind of rolled with the punches, and Americana has gotten its feet.

And Shooter has been miraculous in some of the things that he's yielded already. But Waylon and he both don't go for prizes. They do help you, but you have to have that creative want to.

When he was 16, he didn't want a car; he wanted Pro Tools. So, he started early on his path and is doing great. He was a little before his time in performance and then working through being the son of Waylon Jennings, he worked through that and did great.

He loved his father dearly, and he now is a great spokesman for his father, which I love. But all in all, we'll just have to wait and see what's going to happen around the corner.

On You're The One, Rhiannon Giddens' Craft Finds A Natural Outgrowth: Songwriting