Photo: Jessica Lehrman

interview

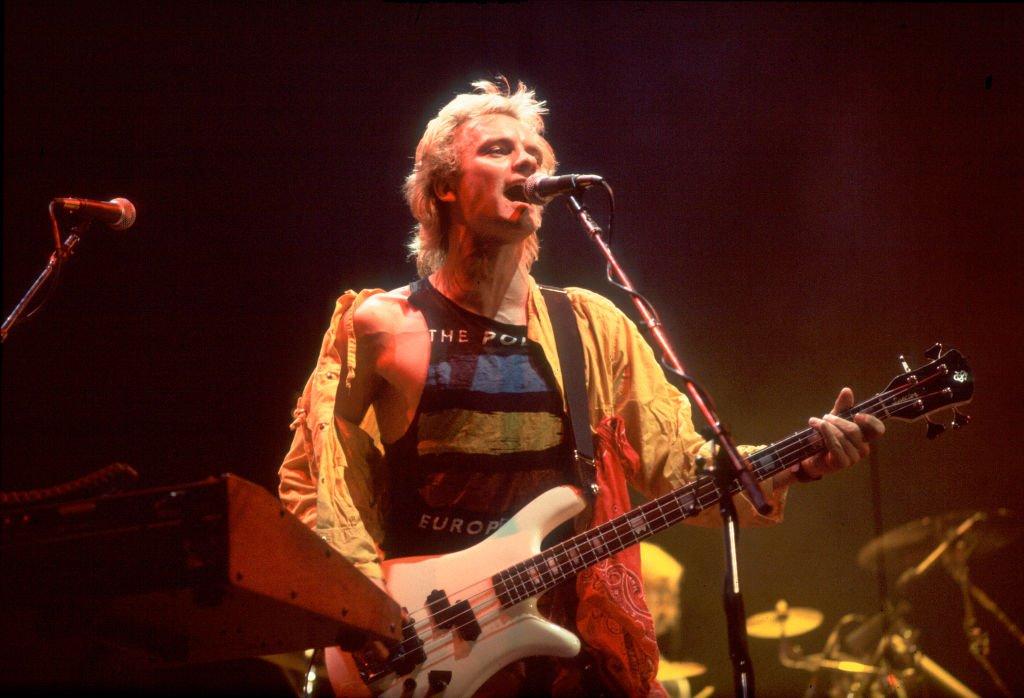

Exclusive: Stewart Copeland Premieres First Single From 'Police Deranged For Orchestra'

The Police founder and drummer Stewart Copeland exclusively shares “Every Breath You Take,” the first single from his forthcoming orchestral re-arrangement of Police songs. The album, 'Police Deranged for Orchestra,' is out June 23.

In November of 1978, the Police made an emphatic statement with their debut album, Outlandos d'Amour, which featured now-classic singles"Roxanne" and "Can’t Stand Losing You." Drawing from the subliminal talents of vocalist Sting, guitarist Andy Summers and drummer Stewart Copeland, the London-based band created a distinctive sound drawing reggae, pop, and punk. Their songs and sound have become classics.

In 2006, Copeland released Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out, a film he created out of Super 8 footage of the band’s early days. The film employed rearranged, or "deranged", versions of the band’s songs to score the film. More than 15 years later, the work evolved into Police Deranged for Orchestra. Copelan's forthcoming album, out June 23, combines his rearrangements with a symphony orchestra and all-star rock band.

The derangements on Police Deranged are far from a paint by numbers revisit of the songs. Rather, Copeland channels his classical and jazz roots in an experimental tweaking of the Police's classics. The resulting songs arrive at exciting sonic destinations with new elements, yet never totally lose sight of the originals.

"I've been mostly erring on the side of pushing it over the edge," Stewart told GRAMMY.com. Indeed, "Message in a Bottle," for example, arrives with a more cinematic atmospheric vibe; its tangents freely wander.

"The hooks of those songs are so strong that I can take wild liberties with every other aspect," he continues. "People are sometimes afraid to look backwards, and that's only a valid fear if you're not going forwards."

In addition to performing with bands, Copeland has a long history of film and compositional work, including the film score for 1987’s Wall Street and the 1983 Francis Coppola directed Rumble Fish. He calls Police Deranged a reflection of his orchestral and arranging work, which has also been an "inevitable byproduct product of scoring for film." He’ll continue the Police theme later this year in the form of Stewart Copeland’s Police Diaries, a new book featuring diary entries from 1976-79.

The seven-time GRAMMY-winning composer discusses his journey revisiting the Police’s music, how he adjusts to playing drums for orchestra, and why he thinks he can push the songs to their limits. Today, GRAMMY.com premieres "Every Breath You Take," the first single from Police Deranged for Orchestra.

Today you're releasing the album's first single, "Every Breath You Take." What was your journey like revisiting the song?

That one I turned over to [conductor and composer] Eímear Noone and Craig Stuart Garfinkel. I had already orchestrated all of the other music and I finally realized, wait a minute, "Every Breath" was never my most fun song to play live. So, at that point, I just handed that one off to professionals. The journey of that one was egging them on and pushing them to get further and further away from the original, which wasn't broke, but that doesn't mean we can't fix it.

And the orchestral interlude was actually conceived of for a stage moment that actually didn't really work. They were going to start playing ["Every Breath"] and then I walk out, but that looks stupid. So, [the song’s prelude’s] just there as an artifact, but it's actually darned beautiful.

So, they were able to find a pretty nice balance between the core of the original and giving it a new spin?

Actually, I haven't been too concerned about that balance. I've been mostly erring on the side of pushing it over the edge because the hooks of those songs are so strong that I can take wild liberties with every other aspect.

What did you learn about the songs while revisiting them?

That Sting is a darn good songwriter. I missed that back in the day. I was at the back of the stage banging s— and all I ever saw was the back of his head.

Doing these derangements really woke me up to the quality of his music. I already knew that, but the lyrics as well. Man, he had a way with words. Don't tell him I said that.

While working on Police Deranged for Orchestra and digging into the band's recordings, it sounds like you gained a deeper appreciation for what made the Police special, from the small details to what each person brought to the band.

Very much so. Both of them, with Andy as well as Sting. Sting turns out to have been a darn good songwriter. But Andy, the colors, the harmonic textures that he brought. He was a one-man orchestra, that guy. And a lot of the orchestrations that I've done are all built on his harmonic voicing and his arpeggiated guitar figures and so on and does sound great in the orchestra.

There were big moments where we just came up with stuff onstage that were very Police-ish because it came from the three of us, but didn’t exist on any record until now.

In what ways did pairing with an orchestra bring out new things from the songs?

The orchestra has its own vocabulary in those swirls and cool swooshes and wangs and bangs. I introduced some elements that are strictly orchestral, just so that you can utilize all of the diverse forms of expression that an orchestra is capable of.

They were all inspired by Andy and Sting. But I also did add a few new ingredients of my own, mostly to do with the orchestration.

Sometimes when artists put songs in a new light, you gain even more appreciation for the song.

Oh yeah, a bunch of stuff. And I want to call those guys back and say, "Hey, guys, all is forgiven." Well, actually, I have called them back and all is forgiven. We actually get along really great now.

Sting is actually very supportive of this mission. He loves to hear his songs performed by other artists, even when they change it up. It makes him feel like Rodgers and Hammerstein, and indeed is of that stature when it comes to songwriting. But yes, getting deep into these songs definitely gave me much more insight into what those guys came up with.

The album features a pretty impressive all-star cast of musicians and vocalists. Can you talk a little bit about some of the players and why you brought them on?

Armand Sabal-Lecco on bass, has been my bass groove for something like 30 years, and he's played with Paul Simon, Seal, Peter Gabriel, just about everybody. He just has that African lilt, which just works for me, and we're real very close friends. But mainly on the bass, he really lights me up, gives me something to work with.

On guitar, Rusty Anderson played in Animal Logic, a band that I had with Stanley Clarke decades ago, and that's where I met him. And we've been chuckle buddies ever since. He's a guitarist who I called when I was doing film scores. When I knew exactly what I wanted, I could play it myself. But when I was stumped, when I didn't know exactly what I wanted, I'd call Rusty and he would come up with something that I never would've dreamed of. He has incredible technique, a really wide vocabulary of style and sound. I guess that's why Paul McCartney likes him so much too.

The ladies are from three different worlds; they're triple scale alpha vocalists here in Los Angeles. Backing singers generally have more technique and more exactitude in their performance than do star singers. So, these women are all really technically proficient, but I egged them on. I exhorted them to step forward, take the mic, grab the spotlight. And they really did. They really did put stuff beyond what you would get from session musicians and they really lit it up, all three women in very different ways.

Amy is the big, huge Earth mother voice. Ashley is a tinkly on top, very agile. In opera, we would call her a coloratura soprano. And Carmel and the alto range, she's the rock upon which all the others build, very solid and with a lot of unique personality. Carmel is into heavy metal and country, so she has a cultural makeup that is very interesting.

I should also mention our conductor, Edwin Outwater. He really brought a lot of extra X factor out of both the singers and the orchestra. When we developed the show originally for live performance, that's what this all came from and what we got organized for, he really worked with the singers to get them confident, because they're complicated arrangements. I'm reproducing Sting's quite exotic, rhythmic phrasing. And for them to learn it took a lot. What conductors do is they bring all the elements together into one thing. And similarly, Craig Stuart Garfinkel, who actually mixed and recorded it. These were people that I really relied on to make it become real. Now we can move on.

*(L-R): Rusty Anderson, Armand Sabal-Lecco and Stewart Copeland performing in the studio | Photo: Jessica Lehrman*

What songs surprised and challenged you most?

"Tea in The Sahara," [from tk year's album] which was always an obscure favorite of mine, became my favorite piece of orchestration. The rolling waves of the sand dunes really inspired the use of the orchestra in that way..

"Message in a Bottle" was like a diamond and I could not mess with it; the form of it is what it has to be. I did mess with the orchestration, with the sound textures and so on, but the song itself resisted all of my attempts at de-arrangement. But I did orchestrate the heck out of it.

Percussion and rhythm are things that overlap in a lot of styles of music. What’s it like playing drums with an orchestra and how do you adjust compared to other forms?

The orchestra sounds bigger and more majestic and has more presence. The actual volume is not so much; the drum set is designed to compete with big amplification. I had to really adjust my technique and there were some unexpected benefits from that. One is that all kinds of techniques that I had learned as a kid, rudiments and so on, things that just don't read in a rock environment, have a place in an orchestral environment.

So, there's all kinds of cool little stuff that I can do with the drums that would never exist in rock 'n' roll. And also, the drums sound better when I'm not trying to kill them. I guess nobody gets a headache with this quieter technique.

In the '80s, you focused more on your classical roots and, later, the film scores. How do you think that decision has made you a more well-rounded musician?

Well, the two informed each other. Like I say, the film music brought me back to orchestra. My daddy raised me to be a jazz musician, which was going fine until I heard Jimi Hendrix. Meanwhile, my mother was playing 20th century classical: Stravinsky, Revel, Debussy and such, and that really stuck emotionally. So that sound of the orchestra was always there in my heart.

But then when I was doing film music, I was pointed in various directions by my bosses, the directors, that I never would've gone voluntarily as an artist or never would've crossed my mind. But when Francis Coppola [whom I worked on the score for Rumble Fish] turns around and says, "I need strings," I went off and learned how to work with strings. And the rest is history, of working with orchestras, because I was told to. And so that's the benefit of going through a phase as a professional [hired gun]. I'm back to being an artist now, where it's my medium. I do what I want and I follow my own artistic instincts, but I learned all this cool stuff when I was an employee.

What do you recall of your first time hearing classical music?

The first time hearing classical music was kind of beyond memory. It was in the house before I remember, but I suppose the first conscious memory that I have is "Carmina Burana" by Carl Orff and crawling around in our house in Beirut, Lebanon, my face in the Persian carpets that my mother bought in Isfahan. I'm looking at one of them right now.But those patterns, the combination on those Persian rugs of chaos and order, are pretty much exactly what my music is all about.

U2 had an interesting quote recently about their new album where they were revisiting their old classics, that a great song is indestructible. Do you agree with that?

A good song is a good song and there are many ways of slicing a really good song. And Sting really appreciates this too. And so, for U2 to go and go back to those great songs and reimagine them was probably very healthy for them artistically.

People are sometimes afraid to look backwards, and that's only a valid fear if you're not going forwards. If you're moving forwards with great velocity, it's fine to look over your shoulder and check out where you've been and put some of that to good use.

You’re going to be touring with the orchestra later this year.

It’s not so much a tour. I mean, I play 20, 25 shows, and they're all individual events. I fly to Atlanta, I play with the Atlanta Symphony, I fly to Cleveland, play with the Cleveland Orchestra, fly to Nashville. Rather than me hiring an orchestra and 50 hotel rooms, they hire me. And I just show up with my singers and guitarists and it's a much better business model.

I'm going down to Cannes to be a judge at the Cannes Series Festival. And then I'm going to play a show in London at the Coliseum in London and then come back. Then this summer, I'm playing an Italian tour and then a one-off date in Luxem.

I imagine each orchestra has their own unique personality.

Yes, they do. In spite of the diligence, they play exactly what I put on the page. And the more detail that I put on the page, the more detail is their performance, and that shapes what they do. They don't just play the notes. And their philosophy, their reason for living is to faithfully execute what they see on the page.

Nevertheless, the Cleveland Orchestra has a different personality from the Atlanta Symphony or the Chicago. They swing together as one thing, and that one thing has a personality. Sometimes the brass are really crisp in this one here and the other one, it's the strings that shine and so on.

You have a few other projects coming up this year, including a reissue on Record Store Day.

Yeah, that's going to be a deluxe version of my [1980 album as] Klark Kent, comprised of the original tracks, plus the demos that I did at home in my home recording studio and various other pieces to go with that.

Ricky Kej — my buddy with whom I won a GRAMMY this year [for Best Immersive Audio Album] and another one last year — is doing a version of the album, which tentatively titled Police: Deranged for Paradise, with the Soweto Gospel Choir and other ethnic artists from around the world. [It is a] completely alternate version of the album, using all of the Derangettes, my American singers and American players, and the Irish Orchestra, but adding these otherworld elements. That's going to be a cool record.

Yeah, it'll be neat to hear those songs in that context as well.

Yeah, absolutely. In Zulu, in Hausa, in Mandarin, in Tamil. That'll be interesting. And Armenian.

This fall you’re releasing a new book, Stewart Copeland’s Police Diaries.

Yes. That's based on my diaries of the starving years of the Police. I've got every day, what concert we played, how much we got paid, how many people were there. I gave myself reviews, but also I've got the receipts for the trucks that I hired. For some reason, I don't throw stuff away and I've still got all this stuff. And they tell an interesting story.

And the main surprise of that story was how we stuck together before we had any idea what music to play. We were playing crap punk songs that I wrote with yelling, because that's what we had to play to get by and get hired and play those clubs. But we bonded musically and starved until Andy joined and he starved with us. And then it was like a year or two into the Police mission that Sting started coming up with those amazing songs that turned everything around for us. So, we bonded musically before we had any idea of what to play.

Ian Munsick Is Bringing The West To The World With 'White Buffalo'

Photo: Axelle/Bauer-Griffin / FilmMagic / Getty Images

list

10 Love Songs That Have Nothing to Do With Love: From "Every Breath You Take" To "Baby It's Cold Outside"

Don't let the song titles fool you. From misogynist attitudes to tales of coercion and even a secret pregnancy, many popular love songs aren't about love at all.

Many studies on love have proven that it seems to be a trait present throughout species. Although it's undeniable that the capacity for love is universal, evidence suggests love manifests differently across individuals. That is why, for many people, love is undefinable, with the word meaning something for one and something else for another.

This point has never been proven more true than in love songs. Numerous musicians and bands have sung about love, but their definition or meaning of the word and yours might be wholly different. You would be surprised to learn how many love songs have absolutely nothing to do with emotional or physical love.

When you delve beneath the surface, "love" songs are sometimes twisted, uncomfortable, sadistic, and unsavory. So, let's look at 10 love songs with nothing to do with love and everything to do with what they shouldn’t.

"Every Breath You Take" - the Police

When the Police released "Every Breath You Take" in 1983, it immediately became a huge hit, reaching No.1 on U.S., UK, Canadian, Irish, and South African charts. On the surface, this song seems romantic, which is why it made its way into numerous movie scenes and weddings, but the lyrics are uncomfortable and prove the song is not actually about love.

Frontman Sting sings, "I'll be watching you," and, "Oh, can't you see, you belong to me?" about the song's object of affection. Rather than lyrics about a lover, it's believed that the song is about a stalker. At the time Sting was suffering a mental breakdown, making the verses infinitely more evil.

In fact, Sting himself said: "I think it's a nasty little song, really rather evil. It's about jealousy and surveillance and ownership."

"Rollercoaster of Love" - Ohio Players

On the surface, the lyrics "It's a rollercoaster ride/we're on top for the moment/ and then we'll take that dive" seem to describe a relationship's exhilarating ups and downs. However, there has been much debate over the years about the true meaning behind the Ohio Players' staple.

The most popular theory is that the song is about life's ups and downs, not love, but we'll never know. According to late frontman Leroy Bronner who wrote the tune, "To this day, I don't know what I wrote." He continued, "The words didn't make sense to me. But it was a hit."

The song also has a much darker recording humor, which further alienates it from the genre of love songs. According to the rumor to which the band responded "No comment," the scream on the track was the sound of a woman being murdered in the recording studio.

The woman's death is an urban legend, but the band decided to leave it in as a joke and as a way to create buzz for the song, with the actual scream belonging to keyboard player Billy Beck.

"Can't Feel My Face" - the Weeknd

The Weeknd is well known for penning lyrics that have multiple meanings, so it's not surprising that his hit track "Can't Feel My Face" isn't really about love.

With the lyrics: "I can't feel my face when I'm with you/But I love it" and "And I know she'll be the death of me, at least we'll both be numb/And she'll always get the best of me; the worst is yet to come." It sounds like a dark love song about a man who is so in love that he loses all control, which is plausible, but it's more likely the song is about cocaine.

According to Billboard, the song is about drug dependency, and the Weeknd is crooning about cocaine and likening it to a bad relationship. The Weeknd had hinted at the song being about drugs when he commented: "I just won a new award for a kids' show, Talking 'bout a face numbing off a bag of blow." Unfortunately, it's not very romantic.

"Umbrella" - Rihanna

Most believe that one of Rihanna's most famous songs is about a woman comforting her partner and explaining that she will be there for him through the good and bad times. "Baby 'cause in the dark you can't see shiny cars/And that's when you need me there. With you, I'll always share," she sings.

However, a few people believe "Umbrella" is about the corruption of a person's soul – Rhianna's in this case. Some believe that the 2007 hit is about Rhianna welcoming the devil into her heart, body, and soul. While this is more of a conspiracy theory than anything else, a pastor recently posted on TikTok that he came back from hell, and "Umbrella" was one of the songs being used to torture individuals.

"All I Wanna Do is Make Love To You" - Heart

If you listen carefully to the lyrics in "All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You," it's clear that the 1990 song actually about deceit.

Nancy and Ann Wilson are singing about being in love with another man who cannot provide her with children because he is impotent — so she finds a willing one-night stand. She sings, "I didn't ask him his name, this lonely boy in the rain." When morning comes, the protagonist says "All I left him was a note/ I told him I am the flower; you are the seed. We walked in the garden; we planted a tree."

After some time has passed, she's unnerved to come across his path, presumably pregnant: "You can imagine his surprise when he saw his own eyes/I said please, please understand/I'm in love with another man/And what he couldn't give me was the one little thing that you can."

"Bad Romance" - Lady Gaga

"Bad Romance" was developed as an experimental pop record featuring elements of German techno and house. With more than 184 million YouTube streams, the 2008 track quickly became one of Lady Gaga's best songs.

On the surface, "Bad Romance" centers on the pull of a love that's bad for you: "I want your ugly, I want your disease/I want your everything as long as it's free/I want your love." However, it's not so straightforward.

Gaga said she drew inspiration from the paranoia she experienced while on tour. She also stated the song is about her attraction to unhealthy romantic romances that are not always about love.

"Young Girl" - Gary Puckett and the Union Gap

Not all love is appropriate, as the song "Young Girl" by Gary Puckett and the Union Gap proves. This 1968 single is wholly inappropriate and creepy (and illegal), but it still managed to become one of the band's best-known songs. In fact, despite the lyrics being more about unsavory infatuation than love, it still reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 (just behind "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay").

Initially, this song doesn't appear inappropriate with lyrics "Young girl, get out of my mind" possibly referencing the romance of a slight age gap. But the group doubles down: "My love for you is way out of line/ Better run, girl/You're much too young, girl."

If these words aren't enough to prove the song is about being infatuated with an underage girl, you might be convinced by lead singer Gary Puckett singing, "Beneath your perfume and make-up you're just a baby in disguise" and "Get out of here before I have the time to change my mind."

"Under My Thumb" - by the Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones have had their share of controversy over the years, and it's not hard to see why when you consider the meaning behind many of their big hits. "Under My Thumb" might have been marketed as a love song, but it's about a relationship rooted in hate and control.

With lyrics such as "Under my thumb/It's a squirmin' dog who's just had her day/Under my thumb/

A girl who has just changed her ways," it's apparent that Mick Jagger is singing less about heartbreak and more about power. The misogyny is so clear in this song that it made it into the book Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women That Love Them.

"Baby It's Cold Outside" - Dean Martin

One of the most popular holiday season love songs, "Baby, It's Cold Outside" was written by Frank Loessser and performed by Dean Martin and Ella Fitzgerald. It's difficult to say if these musicians knew the song's sinister and controversial underbelly.

"Baby It's Cold Outside" is about a man who pressures a woman to stay at his home by any means necessary. The woman in the song tries to give reasons why she cannot stay with lyrics like "My mother will start to worry" and "My father will be pacing the floor." Yet, her concerns are shot down at every turn, with the man using the bad weather outside to keep her captive. Fortunately, the song has been remade with consensual lyrics, thanks to Kelly Clarkson and John Legend.

"You're Gorgeous" - Babybird

This song may have a happy rhythm, but if you pay attention to the lyrics, there is much more to this song than meets the eye. Although the song appears to be about a man who would do anything for his lady love, it is about exploitation.

This song — the British group's biggest hit, from 1996 — is about a sleazy photographer who takes advantage of a young and naive model and photographs her for men's magazines. The lyrics "You got me to hitch my knees up/And pulled my legs apart" details the true nature of this song.

"People should never be told how to interpret a song," Babybird told the blog Essentially Pop. "So, if they thought it was romantic, then fine." He continued, "Sadly, very few people got the true meaning, which is about male predatory behavior, but in popular music, most critics are a little blind to correct interpretation."

Photo: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

feature

Why The Police’s 'Synchronicity' — Their Final, Fraught Masterpiece — Still Resonates After 40 Years

Released on June 17, 1983, 'Synchronicity' became the band’s biggest commercial success. It was also the Police's final album. Forty years since its release, the "dream-like musical tour" remains a culturally significant sonic exploration.

Flash back to December 1982: A band on the brink of breakup arrives on the volcanic island of Montserrat for six weeks to record what would become their final album.

This six-week sojourn was bittersweet for the Police, whose days and nights spent holed up in George Martin’s AIR Studios resulted in Synchronicity. The British rock trio's fifth album took its title from a word coined by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who speculated that paranormal events had a basis in physical nature; its themes nodded to Arthur Koestler’s 1972 book The Roots of Confidence.

This Caribbean retreat proved to be a reflective, if not fortuitous setting — while the volcano was inactive during their sessions, there certainly were a lot of eruptions and hot heads between members. By the time the band arrived on Montserrat, frontman and chief songwriter Sting had outgrown the Police in stature; the trio had also taken a sabbatical to pursue solo projects following the release of 1981's Ghost in the Machine. While recording "Every Breath You Take," Sting and drummer Stewart Copeland came to fisticuffs. No one doubted the end was nigh.

This underlying tension shapes the mood of Synchronicity, and its songs are like a weed in your garden. Even after you pull it out, it always returns to remind you that the struggle is real. Despite these conflicts and the unraveling of the band in real-time, the resulting record was well-received by critics and the public.

Released on June 17, 1983, Synchronicity became the band’s biggest commercial success. The record hit No. 1 on both the U.S. and the U.K. Billboard 200 charts and spent 17 nonconsecutive weeks in the top spot — selling more than eight million copies in the U.S. alone. At the 26th GRAMMY awards, Synchronicity received five nominations and took home three golden gramophones: Best Rock Performance by a Group or Duo with Vocal for "Synchronicity II"; Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal for "Every Breath You Take"; Sting also took home a GRAMMY for Song of the Year for composing this megahit.

This success vaulted the trio to "biggest band in the world" status. But, due to infighting, their domination did not last long. After a world tour throughout 1984 to promote Synchronicity, Sting officially left the band.

Adding to the growing tension, both lead vocalist Sting and guitarist Andy Summers' marriages were collapsing during this period. Betrayal and suffering hang heavy throughout Synchronicity. This is best illustrated in "King of Pain," the final single released from the album, where the imagery of "a little black spot on the sun today" captures Sting’s temporal malaise but remains resonant.

Lyrically, Synchronicity is a final document, even a legacy, made amid creative conflicts and tumultuous times. Yet what makes the record still resonate after four decades is its dense sonic layers and the trio’s musical experimentation that influenced future artists and recordings.

Synchronicity also endures for the way it stands apart from other 1980s modern rock albums. It mingles musical styles — new wave, post-punk, reggae, jazz-fusion, rock, and what, at the time, was labeled world music. The Police had a firm grasp on melodic theory, harmony and were well-versed in the history of the popular song book; these influences all appear and fuse on their collective coda.

Synchronicity is a culmination of all the musical styles that the Police had previously experimented with, plus the addition of many new textures. While their first four studio records fused their reggae and jazz influences with a new wave sound, Synchronicity saw the band generally moving beyond these staccato rhythms, off-beats and improvisations.

Side one opens with the title track and sets the tone for what follows: a musical journey marked by fractured friendships playing out in the atmospheric melodies and the diverse soundscapes that the album travels over a relatively tight 39.5 minutes. Drop the needle on side two, and the first song you hear is the wistful "Every Breath You Take" — one of the most played in radio history, with more than 15 million plays. Many still consider this Sting composition as one of the greatest pop songs ever written.

Lyrically, Sting’s songs are the most cerebral; they are filled with rich imagery and references to literature from past and present. "Tea in the Sahara '' includes nods to American expat Paul Bowles’ "The Sheltering Sky" while "Wrapped Around Your Finger" alludes to Greek mythological creatures. Irish poet William Butler Yeats finds his way on the record too; "Synchronicity II" that closes Side One was inspired by his famous modernist poem "The Second Coming." The mood of the melodies in these tracks reflects the band’s sonic shift. In other songs, the influence of diverse musical styles from world regions beyond North America are also apparent — a territory Sting continued to explore in his career as a solo artist after the Police disbanded.

Synchronicity was also one of the first to see the other two band members contribute a composition — a parting gift of sorts from Sting to his bandmates; a chance to show their songwriting chops.

Summers’ "Mother," — written in 7/4 time signature that is more common in classical music — is not a great song lyrically or musically, but the short and repetitive track somehow fits. Although the guitarist is singing about the troubled relationship he had with his mum, the song’s frenzied pace and his manic screams match the anger and growing animosity between him and Sting, while also alluding to the end of his marriage. Copeland’s "Miss Gradenko" is slightly better than Summers’ song. Lyrically, the two-minute track speaks to Russian repression during the Cold War; musically it features some fine guitar work.

While Copeland and Summers' participation created a bit of inconsistency, particularly when compared to previous releases, their unique approaches and more direct lyrics make the album even more interesting.

Despite these two songs, which beyond adding to the music publishing coffers of Sting’s bandmates, are forgettable, the album is a reverie deserving of repeated listens to uncover all the subtle soundscapes. The National Recording Registry described Synchronicity as "a dream-like musical tour" and the band's sound as "represented, not a pastiche, but a stylistic ethos."

The album was also musically groundbreaking in terms of the tools and toys used in the studio. Just like the addition of keyboards and horns on Ghost in the Machine, this time around it was the first time Sting had used a sequencer ("Walking in Your Footsteps" and "Synchronicity II"). In Stephen Holden’s 4.5 star Rolling Stone review of the album upon its release, the critic summarized the cohesiveness of the record and its songs like this, "each cut on Synchronicity is not simply a song but a miniature, discrete soundtrack," and "Synchronicity is work of dazzling surfaces and glacial shadows." In a RS reader poll later that same year of the greatest records of 1983, the album topped the list.

Synchronicity also captured the zeitgeist. In 1983, unemployment was at a record high and the Cold War lingered, causing global worries of what these superpowers might do next. For many Gen Xers, this LP was one of the first records they purchased at their local shop. And, for many musicians, it meant "everything." The record remains a masterwork and meaningful document.

In 2009, Synchronicity was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall Of Fame. And, in 2023, the Library of Congress selected the album as one of the newest to be included in the United States National Recording Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Exclusive: Stewart Copeland Premieres First Single From 'Police Deranged For Orchestra'

SHAED

Photo: Andrew Lee

news

Up Close & Personal: SHAED Talk New Music, Allyship & Collabs With ZAYN, Sting & Steve Aoki

The "Melt" band reveal how fun it was working with Sting and Steve Aoki on the dance producer's 2019's track "2 In A Million"

Alt-pop trio SHAED consisting of twin brothers Max and Spencer Ernst and Chelsea Lee (who is married to Spencer), had their big break in summer 2018 with their infectious hit "Trampoline." It was followed by a whirlwind 2019, where they played major festivals and shows around the world and dropped some big collabs, including a ZAYN remix of "Trampoline," whose vocals brought new life—and his massive fan base—to it.

Like so many other artists, COVID-19 put a sudden halt on their packed, globe-trotting schedule. The pause and new perspective have proven productive for them, and resulted in a lot of new, yet-to-be-released music.

"We had a group of songs before this whole quarantine situation and we kind of took a deep listen and realized that we wanted to change it up a bit," Chelsea told us. "Most of the songs we've written for this album, we wrote during these crazy months, so it definitely reflects, emotionally and mentally, what we were feeling. These songs really hit home for us and we're super excited to release them."

Read: Aminé Talks New Album 'Limbo,' Portland Protests And Black Lives Matter

We catch up with the Washington D.C.-based group for the latest episode of GRAMMY.com Up Close & Personal interview video series to learn what they've been up to during quarantine—in addition to creating a new album, they've also protesting with local Black Lives Matter marches and been relaxing in their backyard.

Sharing what he learned about being an ally to the Black community, Max said, "I think it's important to listen. There's all these kind of sub-movements within the Black Lives Matter movement that are really important. Black Trans lives Matter, is super important… I think it's important that all these communities within Black Lives Matter, their voices are being elevated."

The "Melt" band also reveal how fun it was like working with Sting and Steve Aoki on the dance producer's 2019's track "2 In A Million." Watch the full conversation above!

"Chelsea loves Sting," Spencer said, smiling. "Steve Aoki is a fan of ours, and he reached out and said he'd love for us to feature on a song. So we were listening to some demos and trying to figure out which one made sense. And then he said, 'Hey, actually hold on, I got a song with Sting.' And that's when Chelsea was like 'We're doing this right away!'"

Ruth Bader Ginsburg Remembered By Barack Obama, Janet Mock, Jennifer Lopez, Elton John & More

Juliana Hatfield

Photo: David Doobinin

news

Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic: Juliana Hatfield Goes Deep On Her New Police Cover Album

The alt-rock veteran cleverly balances some of the GRAMMY-winning band's most iconic hits like "Every Breath You Take," "Roxanne" and "Can't Stand Losing You," with some of their deeper album cuts and B-sides on her latest project

"I'm starting to think I may have finally found my true calling. I think this might be my thing and I'm really enjoying it," Juliana Hatfield mused, with equal parts dry wit and keen self-awareness. This confessional observation comes from the seasoned singer/songwriter/bandleader reflecting on her newest musical endeavor—splitting up her standard album releases with cover albums entirely devoted to a single artist or band.

Following 2018's widely celebrated Juliana Hatfield Sings Olivia Newton-John and this year's Weird, she has once again picked an inspirational muse from her early years around which to craft a lovingly loud collection of guitar-graced tributes.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/os8RRIKdGfI" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

For the second edition in her newfound cover album project, she revisited her formative years' fascination with British rock trio The Police to create Juliana Hatfield Sings The Police. For this engagingly inventive 12-song set, she cleverly balances some of the GRAMMY-winning band's most iconic hits like "Every Breath You Take," "Roxanne" and "Can't Stand Losing You," with some of their lesser known (yet equally emblematic) album cuts and B-sides.

Hatfield has always shown an enthusiast's flair for reinterpretation over the last three decades with Blake Babies, The Juliana Hatfield Three and as a solo artist. Yet the ability to move beyond the single nod of recognition found in a one-off cover song to the full-on deep dive of a full album dedication has allowed the brilliant guitarist and multi-instrumentalist to dismantle and reassemble a legendary songwriting catalog (or two) through her own creative filters.

Read: Nirvana Manager Danny Goldberg Talks 25 Years of 'MTV Unplugged In New York'

Recently, the Recording Academy spoke with the vibrant artist to find out what it was that so deeply drew her to The Police (both as a young fan and as the focus of this album) and how she picked which songs to cover. She also explained what it was like to step into each of the multi-genre musical shoes of Sting, Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland—she performed all of the vocals, guitars and keyboards on the album, as well as over half of the bass and drums.

Juliana Hatfield: Almost immediately after releasing the Olivia Newton-John album, I started thinking about who I should do next. For a while, I was actually thinking of doing Phil Collins, both his solo songs and also his time in Genesis. I had already started to make a list of his songs when one day I was listening to "Long Long Way to Go" from No Jacket Required. Sting sings background vocals on that song and as soon as I heard his voice, I was immediately struck by the thought, "Wait, I should really be doing The Police."

I have much more of a connection to The Police and was a bigger fan of them than I ever was of Phil Collins. Apart from two Genesis albums that I really love, Duke and Abacab, Phil Collins is more of a singles artist to me. But growing up, I was truly fanatical about The Police and had all their albums and knew all the deep cuts. I just switched my brain over to Police mode and that became the new concept.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/OsNQOjFFs9Q" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Once she set her sights on The Police, it might've seemed like the possibilities of whittling down their renowned catalog to just a single LP's worth of cover songs would be a fool's errand. From 1977 to their contentious split in 1986, The Police were regularly atop the singles and albums charts, all five of their studio albums went platinum and they won six GRAMMYs. Their final, 1983 album Synchronicity even knocked Michael Jackson's Thriller out of the top spot on its way to a 17-week stay at No. 1. At the apex of their fame, The Police were often cited as being the biggest band in the world.

However, while Hatfield's song selection process could've been bloated by the riches embodied in The Police's musical successes, she actually had the reverse problem when it came to deciding on the finalized tracklist.

Juliana Hatfield: It was actually a little hard to get the track list up to 12 songs. While there are plenty of great Police songs to choose from, it's kind of intimidating trying to work with most of them. It was hard to get some of those songs to obey me. "It's Alright For You" or "Rehumanize Yourself;" those two were really tricky. The Police versions are so energized and I was worried that I wasn't going to be able to reach the same intensity.

What was created when those three specific guys played together can never be recaptured. With Olivia Newton-John, it was more about highlighting the songwriting and the melodies. With The Police, it's really more about the chemistry between those three guys and that was intimidating to feel like I was never going to capture the right energy.

Since Hatfield played all of the instruments for the majority of the album's tracks, she had a firsthand experience of the interworking of what made The Police's instrumental interplay so unique. Her approach was to sometimes stay true to the eclectic vibrancy of the individual performances and to sometimes completely strip them down to just their essential components.

Other times, as with the case of her punched up, punked out take on the lounge jazz B-side "Murder By Numbers," she reinvented the song completely. It all depended on what the song seemed to be calling for and what performance style rang the truest to her musicianship.

Juliana Hatfield: Sting's basslines are a lot of fun to play. Sometimes they can be very simple, like "Hungry For You," and sometimes they can sound really simple, like "Canary In A Coalmine," but the groove is really tricky to nail. I tried to do that one like a million times but I eventually gave up and asked Ed Valauskas to do it because he's more of a pro bass player than I am. I really love that bassline but it was just too much for me.

Also, some of Andy's guitar parts were challenging because I was playing way out of my comfort zone. Playing the reggae upbeats on "Canary In A Coalmine" or "Rehumanize Yourself"—the rhythm guitar is playing on a syncopated upbeat and that doesn't come naturally to me. Sonically, I also ended up using a cool effect on my guitar that came from a Roland Jazz Chorus amplifier because I was trying to get that signature Andy Summers chorus effect. I'm really into that effect now and I never used to be.

As recognizable as Sting's bass and Summers' guitar work can be, it was Copeland's powerfully distinctive drumming style that imprinted most fully on The Police's overall sound. Dynamic mixed-metered grooves, jazz-infused snare and hi-hat work, punk-fueled fury and syncopated polyrhythms are just a few of the hallmarks of Copeland's wide-ranging skillset that have made him one of the most memorable drummers of the modern rock era—a fact not lost on Hatfield when she was deciding how to approach the drums for each track.

Juliana Hatfield: Starting the whole album off with a drum machine on "Can't Stand Losing You" was my way of saying, "Don't worry. I'm not going to step on your heroes' toes or try to compete with their legacies." It was always weighing on my mind; "How do I interpret Stewart Copeland's beloved, iconoclastic drumming?"

I was worried about pissing off his fans. I knew I was going to have to really strip the drums down and not try to do anything even approaching his style. If you try to mimic him, you'll fail every time.

Along with assessing the notable musical elements of potential songs, she also let the lyrics and subject matter drive the decision for some inclusions. Whether it was the real world, day-to-day themes of systematic oppression and abuses of power or the way that the band dealt with existentialism and romanticism, the longtime alt-rocker picked a few of the songs based on their intense relevancy—both to the current sociopolitical atmosphere and to her individual life.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/57COSaHF0_s" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Juliana Hatfield: I was looking for songs that seemed really relevant and ones that felt current, like "Landlord" and "Murder By Numbers." Those songs spoke to my anger and sense of frustration about how the people with the power and money are totally f***ing everybody over. There are songs about the evils of the ruling elite on here that make me feel murderous and like I just want to punch someone in the face, so I tried to convey that musically.

Also, some of the songs I ended up not doing—"So Lonely' for example—were because I didn't feel like there was enough substance there. "Hole In My Life" is also about being lonely but its way more existential. It's not about missing a specific person, it's about an existential angst. I can still relate to that. The love songs, at this point in my life, I can't relate to them at all. I just don't have those inclinations anymore. I pushed all of those love songs to the side because they weren't speaking to me at this stage in my life.

For the drum and bass duties that she didn't handle herself, she called on Chris Anzalone (Roomful of Blues) and Ed Valauskas (The Gravel Pit) to help her wrangle the right grooves for her reinterpretations. Some of the songs even went through multiple iterations before she achieved exactly what she was looking to accomplish with this musical love letter to her longtime inspirations.

Luckily, after all of the instrumental elements were sorted out, Hatfield was able to focus on the fun of recording the vocal parts that she had been committing to heart-memory since her youth. She even got to whip out some of her high school French for "Hungry For You (J'aurais Toujours Faim De Toi)."

Juliana Hatfield: When I look back at the whole project, it was really fun. However, when I try to analyze the individual tracks, I realize that it was all pretty tricky. A couple of the songs I had to start over after I already had the basic tracks recorded. For "Can't Stand Losing You" and "Next to You," I already had the live drums, bass and guitar recorded and I had to scrap it all and start over with just a drum machine and my own drumming.

I redid all the bass for those as well because something just wasn't working with the original tracks. It was like a puzzle trying to get everything to fit together. Singing them was second nature though. That was the fun part. I have such an affinity for those melodies and know them all by heart. Most of them were even in the range I like singing in.

<blockquote class="instagram-media" data-instgrm-captioned data-instgrm-permalink="https://www.instagram.com/p/B42gFZDA_4x/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" data-instgrm-version="12" style=" background:#FFF; border:0; border-radius:3px; box-shadow:0 0 1px 0 rgba(0,0,0,0.5),0 1px 10px 0 rgba(0,0,0,0.15); margin: 1px; max-width:540px; min-width:326px; padding:0; width:99.375%; width:-webkit-calc(100% - 2px); width:calc(100% - 2px);"><div style="padding:16px;"> <a href="https://www.instagram.com/p/B42gFZDA_4x/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" style=" background:#FFFFFF; line-height:0; padding:0 0; text-align:center; text-decoration:none; width:100%;" target="_blank"> <div style=" display: flex; flex-direction: row; align-items: center;"> <div style="background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 50%; flex-grow: 0; height: 40px; margin-right: 14px; width: 40px;"></div> <div style="display: flex; flex-direction: column; flex-grow: 1; justify-content: center;"> <div style=" background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 4px; flex-grow: 0; height: 14px; margin-bottom: 6px; width: 100px;"></div> <div style=" background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 4px; flex-grow: 0; height: 14px; width: 60px;"></div></div></div><div style="padding: 19% 0;"></div> <div style="display:block; height:50px; margin:0 auto 12px; width:50px;"><svg width="50px" height="50px" viewBox="0 0 60 60" version="1.1" xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg" xmlns:xlink="https://www.w3.org/1999/xlink"><g stroke="none" stroke-width="1" fill="none" fill-rule="evenodd"><g transform="translate(-511.000000, -20.000000)" fill="#000000"><g><path d="M556.869,30.41 C554.814,30.41 553.148,32.076 553.148,34.131 C553.148,36.186 554.814,37.852 556.869,37.852 C558.924,37.852 560.59,36.186 560.59,34.131 C560.59,32.076 558.924,30.41 556.869,30.41 M541,60.657 C535.114,60.657 530.342,55.887 530.342,50 C530.342,44.114 535.114,39.342 541,39.342 C546.887,39.342 551.658,44.114 551.658,50 C551.658,55.887 546.887,60.657 541,60.657 M541,33.886 C532.1,33.886 524.886,41.1 524.886,50 C524.886,58.899 532.1,66.113 541,66.113 C549.9,66.113 557.115,58.899 557.115,50 C557.115,41.1 549.9,33.886 541,33.886 M565.378,62.101 C565.244,65.022 564.756,66.606 564.346,67.663 C563.803,69.06 563.154,70.057 562.106,71.106 C561.058,72.155 560.06,72.803 558.662,73.347 C557.607,73.757 556.021,74.244 553.102,74.378 C549.944,74.521 548.997,74.552 541,74.552 C533.003,74.552 532.056,74.521 528.898,74.378 C525.979,74.244 524.393,73.757 523.338,73.347 C521.94,72.803 520.942,72.155 519.894,71.106 C518.846,70.057 518.197,69.06 517.654,67.663 C517.244,66.606 516.755,65.022 516.623,62.101 C516.479,58.943 516.448,57.996 516.448,50 C516.448,42.003 516.479,41.056 516.623,37.899 C516.755,34.978 517.244,33.391 517.654,32.338 C518.197,30.938 518.846,29.942 519.894,28.894 C520.942,27.846 521.94,27.196 523.338,26.654 C524.393,26.244 525.979,25.756 528.898,25.623 C532.057,25.479 533.004,25.448 541,25.448 C548.997,25.448 549.943,25.479 553.102,25.623 C556.021,25.756 557.607,26.244 558.662,26.654 C560.06,27.196 561.058,27.846 562.106,28.894 C563.154,29.942 563.803,30.938 564.346,32.338 C564.756,33.391 565.244,34.978 565.378,37.899 C565.522,41.056 565.552,42.003 565.552,50 C565.552,57.996 565.522,58.943 565.378,62.101 M570.82,37.631 C570.674,34.438 570.167,32.258 569.425,30.349 C568.659,28.377 567.633,26.702 565.965,25.035 C564.297,23.368 562.623,22.342 560.652,21.575 C558.743,20.834 556.562,20.326 553.369,20.18 C550.169,20.033 549.148,20 541,20 C532.853,20 531.831,20.033 528.631,20.18 C525.438,20.326 523.257,20.834 521.349,21.575 C519.376,22.342 517.703,23.368 516.035,25.035 C514.368,26.702 513.342,28.377 512.574,30.349 C511.834,32.258 511.326,34.438 511.181,37.631 C511.035,40.831 511,41.851 511,50 C511,58.147 511.035,59.17 511.181,62.369 C511.326,65.562 511.834,67.743 512.574,69.651 C513.342,71.625 514.368,73.296 516.035,74.965 C517.703,76.634 519.376,77.658 521.349,78.425 C523.257,79.167 525.438,79.673 528.631,79.82 C531.831,79.965 532.853,80.001 541,80.001 C549.148,80.001 550.169,79.965 553.369,79.82 C556.562,79.673 558.743,79.167 560.652,78.425 C562.623,77.658 564.297,76.634 565.965,74.965 C567.633,73.296 568.659,71.625 569.425,69.651 C570.167,67.743 570.674,65.562 570.82,62.369 C570.966,59.17 571,58.147 571,50 C571,41.851 570.966,40.831 570.82,37.631"></path></g></g></g></svg></div><div style="padding-top: 8px;"> <div style=" color:#3897f0; font-family:Arial,sans-serif; font-size:14px; font-style:normal; font-weight:550; line-height:18px;"> View this post on Instagram</div></div><div style="padding: 12.5% 0;"></div> <div style="display: flex; flex-direction: row; margin-bottom: 14px; align-items: center;"><div> <div style="background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 50%; height: 12.5px; width: 12.5px; transform: translateX(0px) translateY(7px);"></div> <div style="background-color: #F4F4F4; height: 12.5px; transform: rotate(-45deg) translateX(3px) translateY(1px); width: 12.5px; flex-grow: 0; margin-right: 14px; margin-left: 2px;"></div> <div style="background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 50%; height: 12.5px; width: 12.5px; transform: translateX(9px) translateY(-18px);"></div></div><div style="margin-left: 8px;"> <div style=" background-color: #F4F4F4; border-radius: 50%; flex-grow: 0; height: 20px; width: 20px;"></div> <div style=" width: 0; height: 0; border-top: 2px solid transparent; border-left: 6px solid #f4f4f4; border-bottom: 2px solid transparent; transform: translateX(16px) translateY(-4px) rotate(30deg)"></div></div><div style="margin-left: auto;"> <div style=" width: 0px; border-top: 8px solid #F4F4F4; border-right: 8px solid transparent; transform: translateY(16px);"></div> <div style=" background-color: #F4F4F4; flex-grow: 0; height: 12px; width: 16px; transform: translateY(-4px);"></div> <div style=" width: 0; height: 0; border-top: 8px solid #F4F4F4; border-left: 8px solid transparent; transform: translateY(-4px) translateX(8px);"></div></div></div></a> <p style=" margin:8px 0 0 0; padding:0 4px;"> <a href="https://www.instagram.com/p/B42gFZDA_4x/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" style=" color:#000; font-family:Arial,sans-serif; font-size:14px; font-style:normal; font-weight:normal; line-height:17px; text-decoration:none; word-wrap:break-word;" target="_blank">The lady who works in the post office recently read an article about me in which I talked about my new all-Police covers album and also about wanting to cover an as-yet-undetermined American band for my next/future project (since I had done an Australian [Olivia Newton-John] and now an English band). So the postwoman and her husband made a list for me of bands that they think I should consider doing next... and here is the (awesome) list!</a></p> <p style=" color:#c9c8cd; font-family:Arial,sans-serif; font-size:14px; line-height:17px; margin-bottom:0; margin-top:8px; overflow:hidden; padding:8px 0 7px; text-align:center; text-overflow:ellipsis; white-space:nowrap;">A post shared by @<a href="https://www.instagram.com/julianahatfield/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" style=" color:#c9c8cd; font-family:Arial,sans-serif; font-size:14px; font-style:normal; font-weight:normal; line-height:17px;" target="_blank"> julianahatfield</a> on <time style=" font-family:Arial,sans-serif; font-size:14px; line-height:17px;" datetime="2019-11-14T15:53:40+00:00">Nov 14, 2019 at 7:53am PST</time></p></div></blockquote><script async src="//www.instagram.com/embed.js"></script>

With an album concept like Juliana Hatfield Sings The Police, there are immediate "who will be next" questions that naturally follow. While there are always interesting contenders that easily bubble to the surface of conversations with Hatfield, flipping the question inside out—"What band would you like to record a cover album of Juliana Hatfield songs?"—prompted a wonderfully reflective pause and gleefully wishful response.

Juliana Hatfield: I think it would be R.E.M., yeah definitely them. I would want them to do it. In fact, I dare them to do it. They wouldn't, of course, but that would be an absolute dream come true. I would love to hear that in my lifetime.

Juliana Hatfield Sings The Police is currently available on CD, cassette and multiple vinyl variants from American Laundromat Records.

Bad Bunny, Rosalia, Juanes & More: 5 Unforgettable Moments From The 2019 Latin GRAMMYs