As the train of Beatles remixes and expansions — solo or otherwise — chugs along, a fair question might come to mind: why John Lennon's Mind Games, and why now?

When you consider some agreed-upon classics — George Harrison's Living in the Material World, Ringo Starr's Ringo — it might seem like it skipped the line. Historically, fans and critics have rarely made much of Mind Games, mostly viewing it as an album-length shell for its totemic title track.

The 2020 best-of Lennon compilation Gimme Some Truth: The Ultimate Mixes featured "Mind Games," "Out the Blue," and "I Know (I Know)," which is about right — even in fanatical Lennon circles, few other Mind Games tracks get much shine. It's hard to imagine anyone reaching for it instead of Plastic Ono Band, or Imagine, or even the controversial, semi-outrageous Some Time in New York City.

Granted, these largely aren't A-tier Lennon songs — but still, the album's tepid reputation has little to do with the material. The original Mind Games mix is, to put it charitably, muddy — partly due to Lennon's insecurity about his voice, partly just due to that era of recordmaking.

The fourth-best Picasso is obviously still worth viewing. But not with an inch of grime on your glasses.

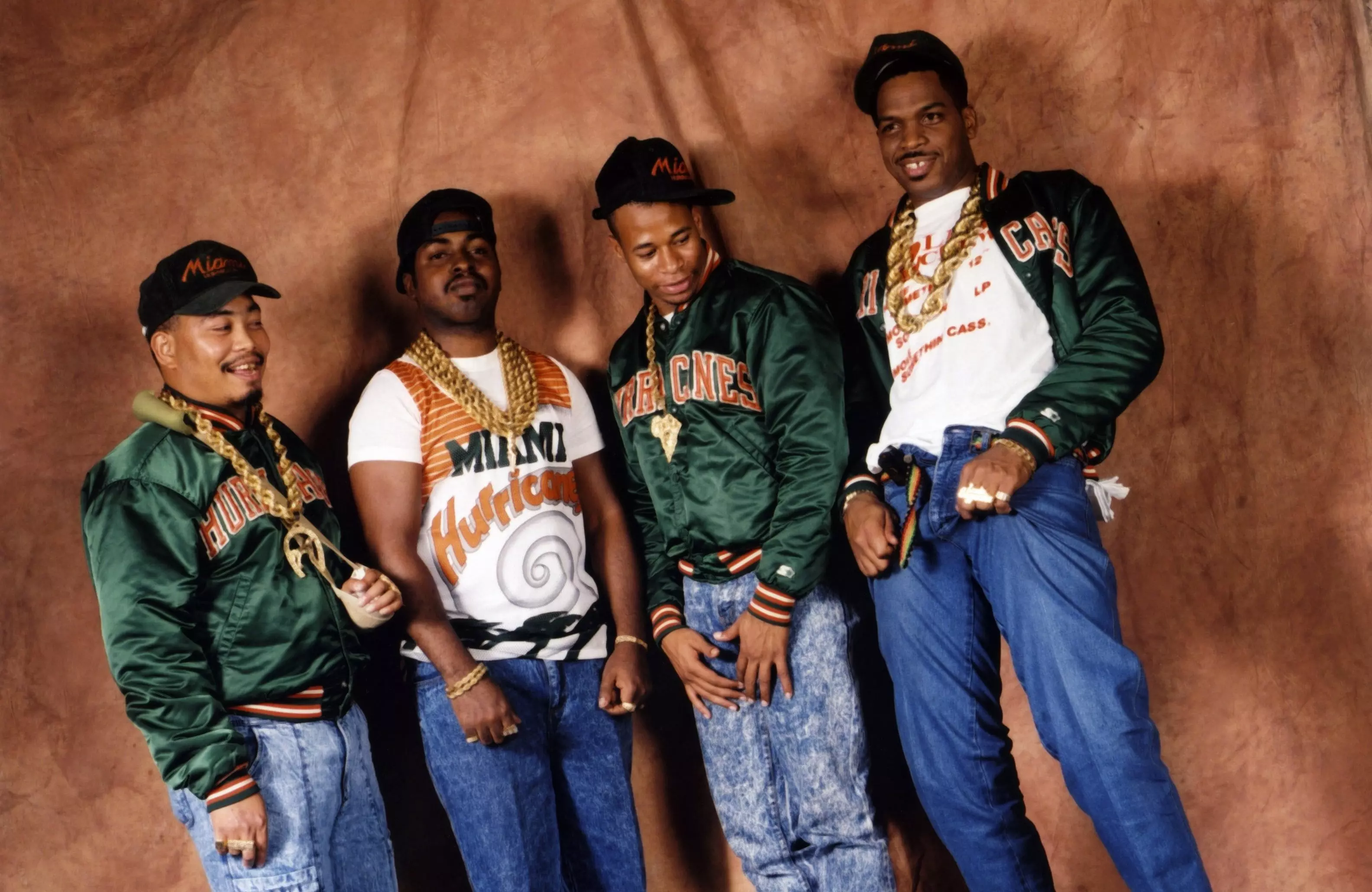

The Standard Deluxe Edition. Photo courtesy of Universal Music Group

That's all changed with Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection — a fairly gobsmacking makeover of the original album, out July 12. Turns out giving it this treatment was an excellent, long-overdue idea — and producer Sean Ono Lennon, remixers Rob Stevens, Sam Gannon and Paul Hicks were the best men for the job. Outtakes and deconstructed "Elemental" and "Elements" mixes round out the boxed set.

It's not that Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection reveals some sort of masterpiece. The album's still uneven; it was bashed out at New York's Record Plant in a week, and it shows. But that's been revealed to not be its downfall, but its intrinsic charm. As you sift through the expanded collection, consider these reasons you should give Mind Games another shot.

The Songs Are Better Than You Remember

Will deep cuts like "Intuition" or "Meat City" necessarily make your summer playlist? Your mileage may vary. However, a solid handful of songs you may have written off due to murky sonics are excellent Lennon.

With a proper mix, "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)" absolutely soars — it's Lennon's slow-burning, Smokey Robinson-style mea culpa to Yoko Ono. "Bring On the Lucie (Freda Peeple)" has a rickety, communal "Give Peace a Chance" energy — and in some ways, it's a stronger song than that pacifist classic.

And on side 2, the mellow, ruminative "I Know (I Know)" and "You Are Here" sparkle — especially the almost Mazzy Star-like latter tune, with pedal steel guitarist "Sneaky" Pete Kleinow (of Flying Burrito Brothers fame) providing abundant atmosphere.

And, of course, the agreed-upon cuts are even better: "Mind Games" sounds more celestial than ever. And the gorgeous, cathartic "Out the Blue" — led by David Spinozza's classical-style playing, with his old pal Paul McCartney rubbing off on the melody — could and should lead any best-of list.

Part of the fun of Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is realizing how great its performances are. They're not simply studio wrapping paper; they capture 1970s New York's finest session cats at full tilt.

Those were: Kleinow, Spinozza, keyboardist Ken Ascher, bassist Gordon Edwards, drummer Jim Keltner (sometimes along with Rick Marotta), saxophonist Michael Brecker, and backing vocalists Something Different.

All are blue-chip; the hand-in-glove rhythm section of Edwards and Keltner is especially captivating. (Just listen to Edwards' spectacular use of silence, as he funkily weaves through that title track.)

The hardcover book included in Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection is replete with the musicians' fly-on-the-wall stories from that week at the Record Plant.

"You can hear how much we're all enjoying playing together in those mixes," Keltner says in the book, praising Spinozza and Gordon. "If you're hearing John Lennon's voice in your headphones and the great Kenny Ascher playing John's chords on the keys, there's just no question of where you're going and how you're going to get there."

It Captures A Fascinating Moment In Time

"Mind Games to me was like an interim record between being a manic political lunatic to back to being a musician again," Lennon stated, according to the book. "It's a political album or an introspective album. Someone told me it was like Imagine with balls, which I liked a lot."

This creative transition reflects the upheaval in Lennon's life at the time. He no longer had Phil Spector to produce; Mind Games was his first self-production. He was struggling to stay in the country, while Nixon wanted him and his message firmly out.

Plus, Lennon recorded it a few months before his 18-month separation from Ono began — the mythologized "Lost Weekend" that was actually a creatively flourishing time. All of this gives the exhaustive Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection historical weight, on top of listening pleasure.

"[It's important to] get as complete a revealing of it as possible," Stevens, who handled the Raw Studio Mixes, tells GRAMMY.com. "Because nobody's going to be able to do it in 30 years."

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in Central Park, 1973. Photo: Bob Gruen

Moments Of Inspired Weirdness Abound

Four seconds of silence titled the "Nutopian International Anthem." A messy slab of blues rock with refrains of "Fingerlickin', chicken-pickin'" and "Chickin-suckin', mother-truckin'." The country-fried "Tight A$," basically one long double entendre.

To put it simply, you can't find such heavy concentrates of Lennonesque nuttiness on more commercial works like Imagine. Sometimes the outliers get under your skin just the same.

Read more: We've Thrown Everything We Could At John Lennon's "Imagine." The Song Nonetheless Endures 50 Years Later.

It's Never Sounded Better

"It's a little harsh, a little compressed," Stevens says of the original 1973 mix. "The sound's a little bit off-putting, so maybe you dismiss listening to it, in a different head. Which is why the record might not have gotten its due back then."

As such, in 2024 it's revelatory to hear Edwards' basslines so plump, Keltner's kick so defined, Ascher's lines so crystalline. When Spinozza rips into that "Aisumasen" solo, it absolutely penetrates. And, as always with these Lennon remixes, the man's voice is prioritized, and placed front and center. It doesn't dispose of the effects Lennon insecurely desired; it clarifies them.

"I get so enthusiastic," Ascher says about listening to Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection. "I say, 'Well, that could have been a hit. This could have been a hit. No, this one could have been a hit, this one." Yes is the answer.

.jpg)

.webp)