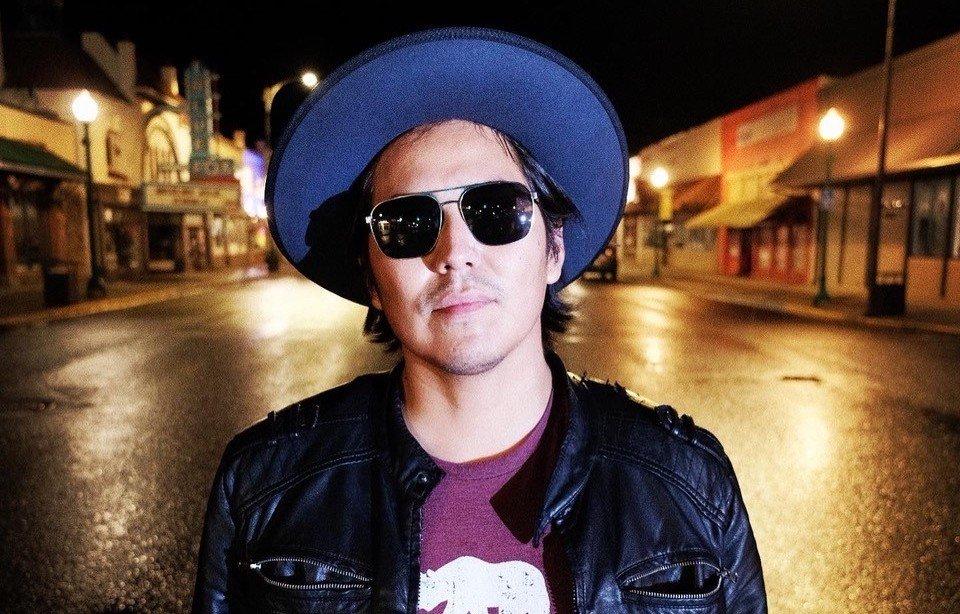

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

Ace Of Cups

news

Fame Eluded The Ace Of Cups In The 1960s. Can They Reclaim It In 2020?

The all-female psychedelic band petered out before making an album. Now, as senior citizens, they’re sharing their second via GRAMMY.com — and they have one hell of a story to tell

Mary Alfiler was in the middle of a rough patch when she found a poem about death written on a bar napkin. "We thank with brief thanksgiving / Whatever gods may be, That no life lives forever / That dead men rise up never / That even the weariest river / Winds somewhere safe to sea,” one verse read. She didn’t know it then, but those words were from “The Garden of Proserpine” by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

At the time, Alfiler — then Gannon — just knew it meant something to her. It was 1971, she was a single mother on food stamps, and her band, the Ace of Cups, was hanging on by a thread. Still, Swinburne’s poem, which she found at the Sleeping Lady Café in Fairfax, California, became the germ of a new song, "Slowest River," which flips the theme of death into one of renewal and return to one's life-source. Forty-nine years later, the stirring piano ballad concludes Sing Your Dreams, a new record by the Ace of Cups. On that track, Jackson Browne shares lead vocals with founding member Denise Kaufman.

Confident, joyful and eclectic, Sing Your Dreams follows the band’s 2018 self-titled debut. The album features reworkings of Ace oldies, like “Waller Street Blues,” and “Boy, What’ll You Do Then”; a trippy devotional to the Feminine Divine (“Jai Ma”); and a fiery call for female leadership (a cover of Keb’ Mo’s “Put a Woman in Charge”). Before it’s released Oct. 2 via High Moon Records, check it out exclusively below via GRAMMY.com.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/kG4r-M0jgUE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Back in the 1960s, the Ace of Cups shared stages with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Big Brother and the Grateful Dead. While they may not appear in biopics and on blacklight posters, the Ace of Cups have something ultimately sweeter than public adulation. Unlike their old associates Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jerry Garcia, who all died too young, the Ace are happy, creative and healthy in their autumn years.

Before the Ace of Cups, hardly anyone had heard of an all-female rock band. In that way, they paved the way for the Runaways, the Go-Go’s, the Slits and so many others. Despite having the talent, the drive and the charisma, the Ace of Cups missed the major-label feeding frenzy that gobbled up many of their Bay Area peers.

Which may have been for the best, they say. "If we had gotten signed, things might have played out differently, Alfiler says. "Knowing me and knowing the way we were acting, we might have gone the way of a lot of bands.”

"A lot of bands that we played with and musicians we loved aren’t even on Earth anymore," Kaufman tells GRAMMY.com. "We’re grateful to all not only be alive but be alive and up for playing."

But as septuagenarians, the Ace of Cups has been given an unlikely second chance in the music business — and they’re seizing it.

Hear Every Sound

From an early age, each Ace member had musical impulses that they struggled to manifest in an uncomprehending world. Alfiler, their bassist and a native of New York state, sang in a girls’ choir that performed Gregorian chants and Irish reels. She longed to play an instrument but hadn’t received piano lessons, and the guitar was out of the question. "I’m not complaining; I’m so happy about my vocal training," she tells GRAMMY.com. "But what opportunities were there for me?" Alfiler went to college out west in Monterey, where she joined a theater group.

Mary Mercy (née Simpson), their lead guitarist, loved Joan Baez and won first prize at a high school talent show for her renditions of "Silver Dagger" and "Banks of the Ohio." In 1964, while attending San Jose State, she saw the Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen play at a coffeehouse owned by his bandmate Paul Kantner, and Kaukonen agreed to give Simpson guitar lessons. "I abruptly left San Jose State, so I never did pay him [for the last lesson]," Mercy tells GRAMMY.com with a laugh. (She’d reimburse him two years later.)

After her lessons with Kaukonen, Mercy functionally learned lead guitar backward. "Most guitar players I ever met would copy every guitar player they heard," she explains. "In a song, I would play whatever notes, but sometimes the notes wouldn’t sound right. So I learned the scales sort of by trial and error. Looking back, I think that was probably a mistake because you have to learn from what other people have done."

Of all their backstories, Kaufman’s is the most bonkers. In her freshman year of college, she was Merry Prankster, traveling on the bus with countercultural figures Neal Cassady (of On the Road fame) and Ken Kesey. Under the name Mary Microgram, she appears several times in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe’s 1968 document of the Pranksters’ hallucinogenic sojourns. “At last Kesey returns with the last to be rescued, Mary Microgram,” one passage reads, “looking like a countryside after a long and fierce war.”

"Neal was tuned in on such an amazing level," Kaufman says. "I’d ride shotgun with Neal and close my eyes. It wasn’t like you were in your thoughts, and he was in his thoughts. He was a weaver, a combiner of consciousness." Soon after Kaufman got off the bus, she sang in a band called Luminous Marsh Gas, which later evolved into Moby Grape.

During her freshman year at UC Berkeley, Kaufman met future Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner and shepherded him through his first acid trip. "I thought it wasn’t a good idea for him to do that himself with no experience," she says. The pair bought a Sandy Bull record, went to his house, and he did the deed. Kaufman and Wenner eventually dated and were briefly engaged until she, in her word, "bailed."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/mqP6npBuZuI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Wenner partly inspired Kaufman’s first solo single, "Boy, What’ll You Do Then," which would become an Ace calling card and appears on Sing Your Dreams. (There are only two known copies of the original 45, one of which recently sold for $10,000; the masters went up in the Oakland fire of 1991.)

Growing up with a white father and a Black stepmother, Ace keyboardist Marla Hanson (née Hunt) was exposed to gospel music and R&B. "I came from a musical family. Everyone played an instrument and sang," she wrote on her website. I’m told that the first song I learned on the piano was Brahms’ ‘Lullaby,’ and by the time I was eight, I had taught myself the first two movements of [Beethoven’s] Moonlight Sonata by listening to a 78 record."

Ace drummer Diane Vitalich got her musical itch watching marching bands. "I could hardly see the drummers’ strokes because they were moving so fast," she tells GRAMMY.com. "They had a little music class in grammar school, and I told them I wanted to play the drums. They said, ‘No, you’re a girl. Girls don’t play the drums.’ I wished I was a boy because my brother could do all these different things I wasn’t allowed to do."

Photo by Casey Sonnabend

The Ace Begins

Alfiler and Hanson were the first two members of the Ace to play together. (Alfiler’s last band was the Daemon Lover, which she joined "because I thought the guitar player was cute.") "Forming an all-woman band was Mary’s idea," Hanson stated in the liner notes of the band’s 2003 odds-and-ends collection It’s Bad For You But Buy It!. "She just talked about having a band like it was the most natural thing in the world."

At this point, the concept for the band was amorphous, even crossing over into performance art. Alfiler once considered wiring up her college friend Val Risely with bird wings to soar over the audience to the folk song "The Cuckoo." One night in 1966, while party-hopping in Upper Haight, Alfiler met a kindred soul and the next member of their nascent band.

"I just wandered into one of these Victorian houses on a side street," she remembers. "They had all the Zig-Zag papers they’d licked all night long to make crepe paper decorations." In one room, she found a girl bashing a drum kit all by her lonesome. That girl was Vitalich, and Alfiler invited her to come over and jam. "It was a very innocent thing," Alfiler says. "We had no image of what we were doing." After transferring from San Jose State for San Francisco City College, Mercy heard through mutual friends about Alfiler and Hanson, called them up, and came over to jam.

Kaufman was the last member to join. At the time, she lived in the psychiatric wing of Mount Zion Hospital, where her parents had committed her due to her LSD use. Before acid attracted rough publicity, Kaufman’s parents were open to it, going as far as to schedule a therapist-supervised psychedelic experience with her. (That therapist, Dr. James Watt, went on to be arrested for possessing 300 milligrams of liquid LSD on his yacht.)

Upstairs at Mount Zion, she met the eccentric beatnik and band manager Ambrose Hollingsworth Redmoon, who had been rendered paraplegic by a 1966 car wreck. As per a family therapy program, Kaufman could keep an organ, a guitar and an amplifier in her room. She could also breeze in and out as she pleased.

On New Year’s Eve 1966, Kaufman attended a party at the proto-metal band Blue Cheer’s house in the Haight. "I wandered upstairs, and that’s where I met Mary Ellen," she says. "I always travel with at least an A harmonica in my purse or pocket in case some guitar player is playing blues in E." Which is just what Mercy was doing, and the two women began to jam.

The five women played together for the first time at Alfiler’s and Hanson’s pad at 1480 Waller Street. "I’ll never forget when [Denise] walked in," Hanson said in a 1995 interview. "She’s wearing cowboy boots, a very short skirt, a wild fur coat and a fireman’s hat. Her hair’s stickin’ straight out on the side. She’s got these big glasses and this big guitar case — she’s like 5’ 3, and it’s almost as big as she is. Even in San Francisco, she stood out."

The fivesome wrote their first song, "Waller Street Blues," about the realities of bohemia in the Haight. "That funky blues described, with a few exaggerations — our life at the time," Alfiler says. No bread, lousy food and a pot bust next door." There was no template for what the five women were doing: the Ace was simply a raw expression of creativity and camaraderie.

"All the social mores about what you were supposed to do, like get a boyfriend, were all out the window," Alfiler says. "It was a brave new world, and we didn’t know where it was going." Even Kaufman admitted to being skeptical: "I couldn’t imagine women playing like that. I’d never seen a woman kick ass on the drums," she says. "I knew there were jazz bands with women and all that, but I’d never seen any women play the kind of music we were playing. I had no context."

As part of the deal with Mount Zion, Kaufman ran the office and did PR at Fantasy Records, taking the bus there every day from the hospital. One of her co-workers was a young John Fogerty, then in the pre-CCR band the Golliwogs, who worked in the vinyl packing room. Upstairs were senior partners Max and Sol Weiss and junior partner Saul Zaentz.

Max Weiss helped the Ace rent their first real gear from an Oakland music shop and let them and the Golliwogs practice at the Fantasy headquarters three nights a week. Hollingsworth became the band’s manager. One night, while the nameless band sang around Hollingsworth's bed, he pulled a Tarot card and passed it to each member. It was the Ace of Cups, which depicts a divine hand holding a cup with five streams of water flowing forth.

The women saw the five streams as representing themselves. As such, the Ace of Cups had a name and a band prayer, which they recited in a circle before every practice: "May the Ace of Cups overflow and fill the world with happiness."

Because he was physically indisposed, Hollingsworth, who also managed Quicksilver Messenger Service, handed the reins to Ron Polte. Polte had been enamored with the Ace ever since he saw them at the Continental Ballroom in Santa Clara in early 1967. “I heard their little tinkling voices, went over and saw all these beautiful women playing music,” Polte remembered in It’s Bad For You But Buy It!’s liner notes. “So at the end of the show, when I was paying Denise, I said, ‘You know, you guys are great.’ And she gave me a big hug and a kiss and said thanks.”

Because the Ace didn’t have an album, promoters had to consider them on face value. “When we were first looking for gigs, Ron called the Peppermint Lounge on Broadway, and the manager said ‘An all-women band? Yeah, we’ll hire them.’” Ron said, ‘Well, do you want them to come in and audition?’ The guy goes, ‘No, no. We’ll hire them, but we want them to play topless.’ Ron called me afterward, and I said ‘Well, we’ll play naked, but we won’t play topless!'"

At their house on Autumn Lane looking toward Mount Tamalpais, the Electric Flag shared the band’s equipment and invited them to their "coming-out party" at Monterey Pop Festival. Vitalich didn’t go, and Kaufman rain checked because she had a sitar lesson that Monday. But Alfiler, Mercy, and Hanson went, and they returned raving about a dazzling new guitarist: Jimi Hendrix.

"We were in their motel room, and I was in the bathroom, just combing my hair or whatever. The window was open, and I heard this guitar player. I go to Mary [Alfiler] and say, ‘We have to go there right now. We have to see who that is!’ We rushed over, and it was Jimi Hendrix playing." One week later, Polte got a call asking if the Ace of Cups would open for Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Panhandle in Golden Gate Park.

Hendrix watched the Ace and became their most high-profile fan, asking if the Experience could use their equipment and running around during their set taking pictures. Sadly, the Ace never got to see them. (“I’ve never seen any photos taken by Jimi Hendrix,” High Moon founder George Wallace remarks.)

Mercy was perturbed by Hendrix’s guitar antics but charmed anyway. "My guitar teacher Namoi Healy had always told me ‘Whenever you play your guitar, when you’re done, put it in its case. Don’t take it to the beach. Take very good care of your guitar,’” she says. “So when he burned his guitar, I thought he must have flipped out or something. I couldn’t fathom it!"

That December, Hendrix raved about the girls to Melody Maker. "I heard some groovy sounds last time in the States, like this girl group, Ace of Cups, who write their own songs and the lead guitarist is hell, really great." To be praised by Hendrix means a guitarist has reached the top of the mountain — a notion that makes Mercy laugh long and hard.

"I just wish, in some ways, that he had just said ‘The Ace of Cups were a great band,'" she demurs. "I don’t think my guitar playing was up to what he said it was. I think he was just being nice."

Later in 1967, the Ace set up their practice space at a hangar in the Sausalito heliport. Word was getting out about the Ace of Cups, and a few potential deals materialized. One day, Capitol Records stopped by the heliport. "They had to leave fast. They said, ‘You have five minutes to play us something,'" Vitalich says. "The song we chose may not have been the best one for them to get who we were. They thought ‘Eh.’ They weren’t that interested."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/oLmHLNX2kdE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Cracks In The Cups

At this point, the Ace of Cups had friends in high places. In 1968, they sang backups on Quicksilver Messenger Service’s “The Fool,” a nearly sidelong jam from their 1968 debut. (They’d later do the same on Jefferson Airplane’s 1969 album Volunteers.) Despite their rising profile, the pressure was mounting to put down their guitars and focus on family. “It was always a dilemma when we were thinking about it,” Kaufman says. “If we got a chance to do that, how would we pull it off?”

Hanson and Alfiler had babies at this point; Hanson’s daughter Scarlet Hunt had been born in April 1968, and Alfiler’s daughter Thelina Allegra arrived on Valentine’s Day 1969. While they had nannies to watch the babies during practices, being away from them on tour was virtually impossible. While Alfiler was nursing Thelina, she had to leave for Chicago to play a festival without her. "That was painful for her," Kaufman says.

“One of the hard things for us which freaked us out whenever we got close to signing a record deal,” Kaufman said in the It’s Bad For You But Buy It! liner notes, “was that in those days, you had to promise that you would tour. So when we began to have kids, it was such a dilemma… they were offering so much money, but it was hard. Even us just going away for short trips was difficult for the babies.”

Friction developed between Kaufman and Hanson. “Marla and I had some difficult times working together,” Kaufman says. “We could spark off each other and write well, but my experience with Marla was that she was volatile, and I could never count on what might happen. That was hard for me. She was a real talent and had wonderful musical gifts, but I never knew if she would give them or withhold them.”

Meanwhile, Polte’s agency West-Pole, which also booked Big Brother and Electric Flag, was, in Alfiler’s words, “disabling themselves” in a cocaine haze. “The drug scene was starting to be pretty bad,” Mercy says. “It was disheartening and just seemed dirty. That bothered me. I used LSD for sure, and I smoked pot, but I didn’t do these harder drugs. I started feeling like I needed to get out of this whole scene.”

At the time, Mercy was in a relationship with Francis Roth, who managed the Bay Area rock band Sons of Champlin, and domesticity was on her mind. “I started feeling like what I was supposed to be doing was having a family and living a life in that way,” she says. “There was a cultural impression of what I should be doing. There was arguing going on. I decided, ‘I don’t need this.”

In 1969, Mercy became the first to leave the Ace. (That fall, she returned briefly for one gig.) “Without [Mercy], it wasn’t the same ever again,” Hanson said in the liner notes. “I got more and more depressed as the weeks and months went on… we had all worked so hard for so many years and still had nothing to show for it.”

That year, Kaufman, who was five months pregnant with her daughter Tora, was shoulder-to-shoulder with 20,000 people at the Altamont Free Concert when a 32-ounce beer bottle landed on her head. The bottle cracked Kaufman’s skull, requiring emergency neurosurgery to remove shards of bone from her brain. If the doctors had used anesthetic, she would have lost her baby. (Over Zoom, Kaufman lifts her hair to show the quarter-sized dent in her head. Today, Tora lives on her Kauai farm and co-owns the music shop Hanalei Strings.)

The following year, the Ace of Cups got their only authentic offer from Saul Zaentz at Fantasy Records. Given this is the same Zaentz, who later sued John Fogerty for performing his own songs, one can imagine how this went down. “They sat down, and they wanted all our publishing!” Kaufman says, and Fantasy made a paltry offer that Polte refused.

Hanson soon exited the band. To fill the void she and Mercy left, three men temporarily join the Ace of Cups — Kaufman’s then-husband Noel Jewkes on horns, guitarist Joe Allegra, and drummer Jerry Granelli on an occasional second drum kit. By 1972, the Ace had evaporated completely. “I wouldn’t say it was a breakup. We just kind of faded out,” Vitalich explains. “The five of us just kind of drifted apart.”

What'll You Do Then?

That year, Alfiler and her baby daughter Thelina flew to her bandmate Denise Kaufman’s house on Kauai with 11 pieces of luggage, including a sitar and tamboura wrapped in blankets. She ended up staying on the island permanently. At that point, Vitalich and Jewkes lived in converted chicken coops outside Kaufman and Jewkes’ house on Creamery Road in San Geronimo Valley. ("There weren’t any chickens in it," she clarifies.) When that living situation ended, Vitalich moved into a tent on the next-door neighbors’ property, where she kept a queen-sized bed, a rug, a dresser and her drum pads.

Vitalich briefly played in the band Saving Grace with Hanson, the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart, Quicksilver’s David Frieberg, and singer Cyretta Ryan, which rehearsed for months, played one gig, and called it a day. Alfiler and Kaufman soon moved to a house in Novato with a woman named Joellen Lapidus, who built ornate dulcimers for Joni Mitchell.

In 1974, Alfiler returned to Marin County for a year; she met her husband Andy on Kauai, he joined her back in California, he returned to the island, and she followed him. She had five more children, taught music at Island School in Kauai, and played in church and local bands. For a year and a half, Alfiler and Kaufman played in the all-women band Tropical Punch, which played at Club Med in Hanalei. But for a while afterward, the two didn’t see much of each other.

“That’s the house where I remember working with Mary Gannon on ‘Slowest River,’” Kaufman says. “When I went to Kauai, I left everything there because I thought I’d be back in a few weeks. I left everything and took my pop-tent, a dulcimer, and my baby.” That Thanksgiving, Alfiler arrived by plane with the remnants of the band.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/nkwcNE1aXfg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In 1972, Mercy lost her son Kodak at 22 months old from a heart condition, a tragedy Alfiler alludes to in the song "Macushla." "At that point, I got into all kinds of spiritual ideas because I kept thinking, ‘What’s the point of life?’ I had a baby die, and I was young,” she says. She attended a three-day Tibetan Buddhist retreat and underwent a series of initiations, including fasting from food and water for a full day. "I remember thinking, ‘I can’t do this. This isn’t for me,'" Mercy says.

For the next 13 years, Mercy, her then-husband Roth and her two children lived rent-free on 120 acres of land in Willow Creek, halfway between the California coast and where she lives now in Weaverville. “That’s where I learned how to can food,” she says. “We had eggs; we had chickens. We had bees; I had a bee suit and gathered honey. It was the back-to-the-land movement, which was one of the things that happened during the ‘60s.”

While in Willow Creek, Mercy played in the country-western band the Cosmic Cowgirls, then moved to Arcata and played in the band Roundup (later called Still Pickin’) then-partner Dave Trabue. She worked in the Behavioral and Social Services department at Humboldt, then in a detox center, as a substance abuse counselor, and as a case manager for behavioral health services.

In 1983, Kaufman moved to a guest house in Laurel Canyon to attend the bass program at Musicians Institute. While in Los Angeles, she taught yoga to Kareem Abdul-Jabaar, Quincy Jones, Jane Fonda, Sting and Madonna. In a 1997 Rolling Stone profile, Madge sang Kaufman’s praises. “She was in one of the first all-female bands,” she said. “Have you heard of the Ace of Cups? They [played] with the Grateful Dead. I like to poke her brain, get information out of her.”

For her part, Hanson spent many of her post-Ace years as the pianist and director of Fairfax Street Choir, a collective she formed in 1972 from jam sessions at the Sleeping Lady. (Alfiler, Vitalich and the Monkees’ Peter Tork also had stints in the choir, which reunited in 2013 for a new album and performance at the Marin County Fair.)

Come the 1990s, “I was living in Hawaii, not connected to anything,” Kaufman says of the band, whose name was quietly bubbling up in music collectors' and historians' circles. She’d heard about Ace of Cups songs, like “Boy, What’ll You Do Then” and “Stones,” circulating among bootleggers under false band names and track titles. In 1997, Kaufman got a letter from Alec Palao, who ran a magazine about the Berkeley music scene, and the pair began a correspondence. Palao knew about their boxes of reel-to-reel tapes and wanted to release some of the music therein.

Palao listened to their assortment of rehearsals, live gigs, and demos and cleaned up the audio. Then, Kaufman tracked down the one collector known to own a copy of “Boy, What’ll You Do Then” and Vitalich came over with an ADAT recorder to capture the audio. Thus, this nearly-lost recording — and so many others — were included on 2003’s It’s Bad For You But Buy It!. One person who eagerly bought it was the eccentric George Wallace, who then was dreaming up his boutique reissue label High Moon Records.

Reading about Kaufman in the liner notes, “I thought ‘Well, this is somebody who knew everybody,’” he says. “Maybe she’ll know where there are some lost tapes from the Avalon Ballroom [or something].” Wallace flew to Los Angeles for dinner with Denise, came to her house, and the pair listened to music all night.

Wallace is still amazed the Ace wasn't successful in the 1960s. “I would think the fact they were all women — and so good! — would make record companies drool,” he says. “No one knows why exactly the Ace didn’t get signed to a record deal. To me, it’s astounding.” He encouraged Kaufman to do more with the Ace and gauge the other members’ interest in continuing it.

An Unlikely Reunion

In 2011, the five original Ace members reunited to perform for Wavy Gravy’s 75th birthday celebration in support of his Seva Foundation. “The reason we could do that show was that George rented us a house and a rehearsal space,” Kaufman says. “It was only because of George’s support that we could do that.” Due to personal differences, Hanson didn’t join the other members for future performances.

About a year after Wavy Gravy’s party, Vitalich, Kaufman, and Mercy began flying to Marin County to jam together. (At that point, Alfiler, who lived 3,000 miles away, “wasn’t in with two feet at all,” Kaufman says. “She was interested, but she wasn’t committing to be part of it. Eventually, she did.”) In 2015, after discussing the matter with Kaufman, Wallace decided to help the Ace make the debut album of their dreams.

And he was the man for the job, Kaufman says. “When he listens to music, he hears things I certainly don’t hear and has such interesting ideas. He believes in artists and artistry. And who else would take a group of women in their seventies and say ‘This music needs to be heard?’”

With Vitalich’s old collaborator Dan Shea behind the boards, the band entered Laughing Tiger Studios in Marin County sans Hanson. “My first thought was ‘What would this record have sounded like if they had recorded it in 1968 or 1969?’” Shea tells The Recording Academy about the experience of recording 2018’s Ace of Cups. “We tried to get the most vintage sound possible, which is harder than you might think.”

On Ace of Cups, Shea ultimately went more George Martin than Nuggets, giving songs like “Pretty Boy,” “Taste of One,” and “Stones” the lavish production he felt they deserved.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/6KqPCFw-VHQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The Ace of Cups had their record release show in 2018. Soon after, their new manager Rachel Anne — who the Ace calls their “un-manager” due to being unmanageable — took the septuagenarians on a West Coast tour. At the time, Shea filled in on the keyboard but didn’t want to commit to touring. Dallis Craft, a Bay Area musician who is more than a dozen years the others’ junior, stepped up as their fifth member.

Photo by Jamie Soja

"I’ve always been a scrapper, making my living making music,” Craft tells GRAMMY.com. "I guess people floated my name around." She sees herself as the glue between the larger-than-life personalities in the Ace. “I’m just a happy first mate or whatever. Just tell me what to do to facilitate this whole thing, and I’m there. They’re strong. And it’s so good for me to be around strong women because I’m not.”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/POUghoLOC60' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In February of 2019, the Ace played at the Mercury Lounge and Rockwood Music Hall in New York. That November, they returned to perform on The Today Show. “That was the biggest gig,” Alfiler says. “The big time, right? I met all these people, normal people with headphones on, running around. Everything’s on time; the makeup is downstairs. Maybe in my 20s, I would have thought it was the cat’s meow, but now it’s like ‘Thank you for doing this because I know what it is. It’s so hard.'"

“They schlepped all their gear,” Rachel Anne says. “We sometimes fight because they do shit and I’m like ‘‘Could you please not touch anything? We have roadies.’ I would go in with a load, come back, and there they’d be, like a trail of ants, carrying their gear. They’d say things like ‘Rachel, we’ve been schlepping our gear for 50 years! Back off!’ I’m like, ‘I can’t let anything happen to you!'"

Singing Their Dreams

For Sing Your Dreams, Shea adopted what he calls "a more contemporary approach." "There are more songs that they’ve written in the past 20 years as opposed to 50 years ago,” he says, despite two of the first songs they ever wrote, “Gemini” and “Waller St. Blues,” popping up on the tracklist. “I would say it’s less produced than a lot of the songs on the first record.”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/s2E8LpjhnDA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Kaufman calls “Jai Ma” a “sort of Latin, sort of African, sort of Sanskrit, sort of Yogic dance to the feminine.” “It’s looking again at the story of Eve and the apple,” she explains. “In many cultures and traditions coming from patriarchy through thousands of years, women are kind of blamed or demeaned or made nameless. She brings up the story of Siddhartha, specifically his harem of women from whom he flees in disgust: “I always wondered when I heard that story, ‘What are their names? What do they want?’”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/K7ailgfJQck' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

“Basic Human Needs” was written by Wavy Gravy in response to the bombing of a North Vietnamese hospital on Christmas Day 1972. “He’s a writer, but that was his only song, I think,” Kaufman explains. “He’s sung it through the years, but we wanted to do something with it.” This take of “Basic Human Needs” is its first recorded performance; Gravy sings the lead vocal and plays the “ektar,” his trademark one-stringed instrument.

Alfiler’s “I’m On Your Side” has an old Hollywood feel that recalls her theatrical background. “I had worked hard to bring in a collection of six original songs to play for Dan Shea in hopes that one or two would make it on to this second album,” she says. “One of the last songs we listened to was a ukulele ditty that I had written for my children and grandchildren. That’s the one he liked!"

Vitalich wrote “Little White Lies” about a real-life boyfriend who pulled the wool over her eyes. “I was heading to the movies to catch up with Mr. Wrong, as our roommate said he had gone to the theater. I couldn’t find him at first, but there he was, sitting embraced in the arms of another woman. I asked myself if I should make a scene, but to my surprise, I turned around and walked out of the theater with an overwhelming feeling of freedom,” she continues. “How could this be when I believed it would destroy me?”

The band updated “Waller Street Blues” with lyrics about the realities of the Bay Area in 2020. “I don’t know if you got our snarky little things about the tech invasion,” Kaufman says. “In the early days, Mary’s rent was, like, $45 a month. Maybe it was $45 each for two people, but it was not much. I look at young artists and creatives and think about how much energy they have to [expend] to have a space to work. Do they have time after paying for that loft or warehouse to be able to do their art? In those days, it was much easier.”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/lyysX0tOwMs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Then, of course, there’s “Slowest River / Made For Love.” To avoid words that sound too “ancient,” the Ace tweaked a few lyrics, including the final verse: “Even the slowest river winds ever to the sea.” They also released the “Made For Love” half of the song in advance to comment on our very trying year. “I’m glad we’re able to release it now because these are narrow places, these times,” Kaufman says. “We’re pressed in from all sides, and we need to hold on to our souls.”

After The Storm

As the COVID-19 lockdown approaches the seven-month mark, the Ace of Cups are doing what they’ve always done — playing music, staying active and hanging out with their children and grandchildren. They’re all communicating and collaborating over email; Vitalich is learning GarageBand and recording a new song called “After the Storm” about getting to the other side of the pandemic.

“I’m starting to record it in my home studio with the harmony parts,” she says. “I want to put it out there because it’s positive and might give hope.” She hopes it’ll make their eventual third album.

Because the Ace is his passion project, Wallace is anxious that they haven’t risen to the level of popularity he expected. Kaufman isn’t bothered by this in the slightest. “I don’t know what it takes to be popular in today’s music world,” she says. “We’re not in this to take the record industry by storm. We’re in this to share something real that’s authentic for us to sing about.”

Alfiler is even more Zen about the matter: “I can’t look further than two, three, or four years. We’re in our mid-70s. I’m the oldest. If it’s something I can put in the world that’s of value, I want to do it. If other people can do it better, then that’s fine too.”

She says this in paradisaic climes 3,000 miles from the nearest landmass, separated by decades from that night at the Sleeping Lady. As music careers go, the Ace of Cups’ is the slowest river imaginable, but it flowed into something like contentment.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/sOspr-9S0z4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Jacob Shije

interview

Meet Levi Platero, A Formidable Guitarist Bringing Blues-Rock To The Navajo Nation

"I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar," the guitar scorcher tells GRAMMY.com. But limelight or not, Levi Platero's illuminating a path forward for blues-rock in Indigenous communities.

Back in 2022, Levi Platero spoke to GRAMMY.com about his then-new album, Dying Breed. Two days later, a city bus slammed into his touring van.

The Arizonan blues-rock guitarist, who hails from the Eastern Agency of the Navajo Nation, was on a West Coast tour. After lunch in downtown Portland, kaboom: their van was totaled. When hearing about this close call, something poignant Platero had said came to mind.

"I just want to be able to keep going, man. Especially with blues music, you can kind of play forever," he expressed near the end of the interview. "Not to put down any other musical genres, but I can't see myself being a rap artist at, like, 60 or 70 years old. I can see myself being a blues-rock guy until the day I die."

Looking decades into the future, it's hard not to imagine Platero and his music being buoyed by the community he helped create.

An absolute burner on his instrument — behold Dying Breed highlights like "Fire Water Whiskey" and "Red Wild Woman" as examples — he stands with few others as a blues-rock great in the Navajo Nation. Or just one, in his estimation: Mato Nanji of the band Indigenous, who he affectionately calls "Big Brother."

Perhaps Platero — who's eyeing a new van, and getting ready to head back into the studio in late spring — will also inspire others in his wake. And the more he sings and plays, the more likely that outcome seems — that his "dying breed" will flourish forever.

Read on for an in-depth interview with Platero about his latest album, how Indigenousness inspires his artistry, and why he "doesn't want to be a superstar — I just love to play."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about your background, and the musical community that brought you up.

I grew up in church. My dad was an evangelist. He went out, did things for the church and that kind of community. I would sometimes tag along, but I was getting involved with some of the worship leading and stuff like that. But my dad would write his own tunes, and he would make his own music later on. And I would go out and help him just play drums. I was just in the background area.

Later on, I started playing guitar, and listening to a lot of old gospel tunes and gospel hymns. That's where I got introduced to the blues. And after I learned about the blues, from then on, that's all I ever really listened to.

Now, a lot of things have changed. I'm out in the world doing my own thing and writing my own music about some things that I feel — not necessarily anything that has to do with the church community. But, that's where I got started.

What's your conception of the blues? To me, it's kind of like the word punk. It can be a certain way of playing power chords, or an entire state of being — an opposition to the status quo. Likewise, the blues can mean 12 bars, or the totality of human angst.

I think it's probably the rawest form of musical emotion that I can feel — that I've ever really felt for myself. But that's only my own opinion. That's my perception of it. I always hear a lot of people say that it's a little redundant, and it's kind of boring and whatnot. But for me, it's something that's just really raw, emotional, really straightforward.

And as far as the lifestyle, I mean, I would have to say that being a part of a blues community, I'm really [grounded among] people who are really respectful.

And the people who are respected the most are the people who generally [may] not have the most talent, but collectively, they're a great person — they have a great personality. They really enjoy one another's music, and they're really involved in the blues community where they help each other out, or they get each other's gigs, they sit in.

It's just this really friendly dynamic in that area. Rather enjoyable. I love it.

Living or dead, whether you know them or not, who are the guitarists that formed you?

I have to say my biggest influence was Mato Nanji from Indigenous. They were a Native American blues-rock group back in the day, probably in the early 2000s. They made a really good name for themselves in the blues circuit, and I [had] the opportunity to actually travel and open up for him and also join his band.

I really learned a lot from kind of hanging out with him and just being a part of his group. He's one of my biggest guitar influences and as a person — as a role model.

Otherwise — people who I have not met — I have to say, of course, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan. David Gilmour was a good influence. Doyle Bramhall II — little Doyle, big Doyle.

And then as far as in my community, back in Albuquerque, Darin Goldston — he plays for the Memphis P-Tails. He hosts the blues jam every Wednesday night. Whoever is upcoming and just wants to play some blues, they come out and jam. It's pretty awesome.

And, of course, Ryan McGarvey. If you don't know who that is, he's in the blues-rock circuit. He's a great guy — a pretty influential person.

With all those inspirations on the table, how did you start to develop your own voice on the guitar?

Just being well-seasoned, I guess. Just constantly playing over time. For some people, it doesn't happen right away, to find their own sound. With other people, they have to go through seasons and learn new things, until one day, they really become identifiable just by the first couple of notes they play.

I don't think it was a hard thing for me. I was just playing until it started becoming identifiable to some people's ears.

I'm sure specifically Indigenous influences must make it into your sound in some way.

Yeah, of course. I mean, those drum patterns, those drum beats — they're really similar to all that chain gang stuff they used to do back in the day. Those call-and-repeats and stuff like that.

Sometimes I try to incorporate that into some of the music I have. Indigenous influences are there, as far as jewelry and hats. Even as far as a little bit of graphic design. That stuff definitely makes its way into the fashion part, and the promotion.

Tell me what you were trying to artistically impart with Dying Breed.

I just wanted to put out an album, because I need to. I love writing my own music, and of course, the ultimate goal is to make music that inspires and reaches people — and also inspires Indigenous artists and people at reservations to go after whatever they want to go after.

Because it's like: yeah, there's education on the rez, but as far as outlets — fashion, music, art, film — some of those things don't make it as far as the reservation.

So, just being an Indigenous artist in itself — to be able to write and put out music like that, for others to hear — I guess that's kind of the ultimate accomplishment in what I'm trying to do. Just to keep inspiring people — inspiring my own people, natives all across the U.S.

**Can you talk about your collaborators on Dying Breed?**

That's actually kind of funny, because I'm doing most of the work on the album.

I did all the guitars. I did all the bass guitars. I did the lead vocals. My cousin [Royce Platero] did the drums. I only had my rhythm player [Jacob Shije] play on, like, two tracks, and he was only doing small-fill guitars and that's it. I had a good friend of mine named Tony Orant come in and play keys on two of the songs as well.

As far as all the songs go, I wrote all of them. I composed everything. I came up with the arrangements and the core progressions. I mean, it's all mine.

One of my favorite people and producers right now, a sound engineer who helped me with the album: his name is Ken Riley and he's based out of Albuquerque. He has a really beautiful and awesome old adobe recording studio, right by the Rio Grande. It's called Rio Grande Studios. He's kind of a legend. He's worked with so many artists and still works with big-name, major artists.

I think he recently just worked on Micki Free's album. He worked on a couple of songs with Santana and Gary Clark Jr. Christone ["Kingfish"] Ingram. He works with some heavy hitters, and I approached him. I was introduced to him by a friend of mine named Felix Peralta. He told me to meet this guy and said, "You need to do your next record here."

So, we finally got to meet, me and Ken, and it just kind of went from there and everything came out really good. I really enjoy this record. It's probably my favorite one that I've done so far.

*Levi Platero. Photo: Jacob Shije*

Are there any other Indigenous musicians in the blues and/or Americana world that you want to shout out in this interview?

Foremost, as far as blues guitarists: I have to give a shout-out to my — I call him Big Brother. Mato Nanji, and that means "standing bear." He's a big role model, and probably the only other Indigenous blues-rock guitarist out there besides me who is trying to do it.

Anything else you want to mention before we get out of here?

No, I just want to keep playing. I just want to keep doing this — meet more people, keep expanding. I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar. I just love to play. I just want people to enjoy my music and come vibe at the shows. That's it.

Photo: Rachel Kupfer

list

A Guide To Modern Funk For The Dance Floor: L'Imperatrice, Shiro Schwarz, Franc Moody, Say She She & Moniquea

James Brown changed the sound of popular music when he found the power of the one and unleashed the funk with "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." Today, funk lives on in many forms, including these exciting bands from across the world.

It's rare that a genre can be traced back to a single artist or group, but for funk, that was James Brown. The Godfather of Soul coined the phrase and style of playing known as "on the one," where the first downbeat is emphasized, instead of the typical second and fourth beats in pop, soul and other styles. As David Cheal eloquently explains, playing on the one "left space for phrases and riffs, often syncopated around the beat, creating an intricate, interlocking grid which could go on and on." You know a funky bassline when you hear it; its fat chords beg your body to get up and groove.

Brown's 1965 classic, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," became one of the first funk hits, and has been endlessly sampled and covered over the years, along with his other groovy tracks. Of course, many other funk acts followed in the '60s, and the genre thrived in the '70s and '80s as the disco craze came and went, and the originators of hip-hop and house music created new music from funk and disco's strong, flexible bones built for dancing.

Legendary funk bassist Bootsy Collins learned the power of the one from playing in Brown's band, and brought it to George Clinton, who created P-funk, an expansive, Afrofuturistic, psychedelic exploration of funk with his various bands and projects, including Parliament-Funkadelic. Both Collins and Clinton remain active and funkin', and have offered their timeless grooves to collabs with younger artists, including Kali Uchis, Silk Sonic, and Omar Apollo; and Kendrick Lamar, Flying Lotus, and Thundercat, respectively.

In the 1980s, electro-funk was born when artists like Afrika Bambaataa, Man Parrish, and Egyptian Lover began making futuristic beats with the Roland TR-808 drum machine — often with robotic vocals distorted through a talk box. A key distinguishing factor of electro-funk is a de-emphasis on vocals, with more phrases than choruses and verses. The sound influenced contemporaneous hip-hop, funk and electronica, along with acts around the globe, while current acts like Chromeo, DJ Stingray, and even Egyptian Lover himself keep electro-funk alive and well.

Today, funk lives in many places, with its heavy bass and syncopated grooves finding way into many nooks and crannies of music. There's nu-disco and boogie funk, nodding back to disco bands with soaring vocals and dance floor-designed instrumentation. G-funk continues to influence Los Angeles hip-hop, with innovative artists like Dam-Funk and Channel Tres bringing the funk and G-funk, into electro territory. Funk and disco-centered '70s revival is definitely having a moment, with acts like Ghost Funk Orchestra and Parcels, while its sparkly sprinklings can be heard in pop from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, and, in full "Soul Train" character, Silk Sonic. There are also acts making dreamy, atmospheric music with a solid dose of funk, such as Khruangbin’s global sonic collage.

There are many bands that play heavily with funk, creating lush grooves designed to get you moving. Read on for a taste of five current modern funk and nu-disco artists making band-led uptempo funk built for the dance floor. Be sure to press play on the Spotify playlist above, and check out GRAMMY.com's playlist on Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

Say She She

Aptly self-described as "discodelic soul," Brooklyn-based seven-piece Say She She make dreamy, operatic funk, led by singer-songwriters Nya Gazelle Brown, Piya Malik and Sabrina Mileo Cunningham. Their '70s girl group-inspired vocal harmonies echo, sooth and enchant as they cover poignant topics with feminist flair.

While they’ve been active in the New York scene for a few years, they’ve gained wider acclaim for the irresistible music they began releasing this year, including their debut album, Prism. Their 2022 debut single "Forget Me Not" is an ode to ground-breaking New York art collective Guerilla Girls, and "Norma" is their protest anthem in response to the news that Roe vs. Wade could be (and was) overturned. The band name is a nod to funk legend Nile Rodgers, from the "Le freak, c'est chi" exclamation in Chic's legendary tune "Le Freak."

Moniquea

Moniquea's unique voice oozes confidence, yet invites you in to dance with her to the super funky boogie rhythms. The Pasadena, California artist was raised on funk music; her mom was in a cover band that would play classics like Aretha Franklin’s "Get It Right" and Gladys Knight’s "Love Overboard." Moniquea released her first boogie funk track at 20 and, in 2011, met local producer XL Middelton — a bonafide purveyor of funk. She's been a star artist on his MoFunk Records ever since, and they've collabed on countless tracks, channeling West Coast energy with a heavy dose of G-funk, sunny lyrics and upbeat, roller disco-ready rhythms.

Her latest release is an upbeat nod to classic West Coast funk, produced by Middleton, and follows her February 2022 groovy, collab-filled album, On Repeat.

Shiro Schwarz

Shiro Schwarz is a Mexico City-based duo, consisting of Pammela Rojas and Rafael Marfil, who helped establish a modern funk scene in the richly creative Mexican metropolis. On "Electrify" — originally released in 2016 on Fat Beats Records and reissued in 2021 by MoFunk — Shiro Schwarz's vocals playfully contrast each other, floating over an insistent, upbeat bassline and an '80s throwback electro-funk rhythm with synth flourishes.

Their music manages to be both nostalgic and futuristic — and impossible to sit still to. 2021 single "Be Kind" is sweet, mellow and groovy, perfect chic lounge funk. Shiro Schwarz’s latest track, the joyfully nostalgic "Hey DJ," is a collab with funkstress Saucy Lady and U-Key.

L'Impératrice

L'Impératrice (the empress in French) are a six-piece Parisian group serving an infectiously joyful blend of French pop, nu-disco, funk and psychedelia. Flore Benguigui's vocals are light and dreamy, yet commanding of your attention, while lyrics have a feminist touch.

During their energetic live sets, L'Impératrice members Charles de Boisseguin and Hagni Gwon (keys), David Gaugué (bass), Achille Trocellier (guitar), and Tom Daveau (drums) deliver extended instrumental jam sessions to expand and connect their music. Gaugué emphasizes the thick funky bass, and Benguigui jumps around the stage while sounding like an angel. L’Impératrice’s latest album, 2021’s Tako Tsubo, is a sunny, playful French disco journey.

Franc Moody

Franc Moody's bio fittingly describes their music as "a soul funk and cosmic disco sound." The London outfit was birthed by friends Ned Franc and Jon Moody in the early 2010s, when they were living together and throwing parties in North London's warehouse scene. In 2017, the group grew to six members, including singer and multi-instrumentalist Amber-Simone.

Their music feels at home with other electro-pop bands like fellow Londoners Jungle and Aussie act Parcels. While much of it is upbeat and euphoric, Franc Moody also dips into the more chilled, dreamy realm, such as the vibey, sultry title track from their recently released Into the Ether.

Photo: Steven Sebring

interview

Living Legends: Billy Idol On Survival, Revival & Breaking Out Of The Cage

"One foot in the past and one foot into the future," Billy Idol says, describing his decade-spanning career in rock. "We’ve got the best of all possible worlds because that has been the modus operandi of Billy Idol."

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com spoke with Billy Idol about his latest EP, Cage, and continuing to rock through decades of changing tastes.

Billy Idol is a true rock 'n' roll survivor who has persevered through cultural shifts and personal struggles. While some may think of Idol solely for "Rebel Yell" and "White Wedding," the singer's musical influences span genres and many of his tunes are less turbo-charged than his '80s hits would belie.

Idol first made a splash in the latter half of the '70s with the British punk band Generation X. In the '80s, he went on to a solo career combining rock, pop, and punk into a distinct sound that transformed him and his musical partner, guitarist Steve Stevens, into icons. They have racked up multiple GRAMMY nominations, in addition to one gold, one double platinum, and four platinum albums thanks to hits like "Cradle Of Love," "Flesh For Fantasy," and "Eyes Without A Face."

But, unlike many legacy artists, Idol is anything but a relic. Billy continues to produce vital Idol music by collaborating with producers and songwriters — including Miley Cyrus — who share his forward-thinking vision. He will play a five-show Vegas residency in November, and filmmaker Jonas Akerlund is working on a documentary about Idol’s life.

His latest release is Cage, the second in a trilogy of annual four-song EPs. The title track is a classic Billy Idol banger expressing the desire to free himself from personal constraints and live a better life. Other tracks on Cage incorporate metallic riffing and funky R&B grooves.

Idol continues to reckon with his demons — they both grappled with addiction during the '80s — and the singer is open about those struggles on the record and the page. (Idol's 2014 memoir Dancing With Myself, details a 1990 motorcycle accident that nearly claimed a leg, and how becoming a father steered him to reject hard drugs. "Bitter Taste," from his last EP, The Roadside, reflects on surviving the accident.)

Although Idol and Stevens split in the late '80s — the skilled guitarist fronted Steve Stevens & The Atomic Playboys, and collaborated with Michael Jackson, Rick Ocasek, Vince Neil, and Harold Faltermeyer (on the GRAMMY-winning "Top Gun Anthem") — their common history and shared musical bond has been undeniable. The duo reunited in 2001 for an episode of "VH1 Storytellers" and have been back in the saddle for two decades. Their union remains one of the strongest collaborations in rock 'n roll history.

While there is recognizable personnel and a distinguishable sound throughout a lot of his work, Billy Idol has always pushed himself to try different things. Idol discusses his musical journey, his desire to constantly move forward, and the strong connection that he shares with Stevens.

Steve has said that you like to mix up a variety of styles, yet everyone assumes you're the "Rebel Yell"/"White Wedding" guy. But if they really listen to your catalog, it's vastly different.

Yeah, that's right. With someone like Steve Stevens, and then back in the day Keith Forsey producing... [Before that] Generation X actually did move around inside punk rock. We didn't stay doing just the Ramones two-minute music. We actually did a seven-minute song. [Laughs]. We did always mix things up.

Then when I got into my solo career, that was the fun of it. With someone like Steve, I knew what he could do. I could see whatever we needed to do, we could nail it. The world was my oyster musically.

"Cage" is a classic-sounding Billy Idol rocker, then "Running From The Ghost" is almost metal, like what the Devil's Playground album was like back in the mid-2000s. "Miss Nobody" comes out of nowhere with this pop/R&B flavor. What inspired that?

We really hadn't done anything like that since something like "Flesh For Fantasy" [which] had a bit of an R&B thing about it. Back in the early days of Billy Idol, "Hot In The City" and "Mony Mony" had girls [singing] on the backgrounds.

We always had a bit of R&B really, so it was actually fun to revisit that. We just hadn't done anything really quite like that for a long time. That was one of the reasons to work with someone like Sam Hollander [for the song "Rita Hayworth"] on The Roadside. We knew we could go [with him] into an R&B world, and he's a great songwriter and producer. That's the fun of music really, trying out these things and seeing if you can make them stick.

I listen to new music by veteran artists and debate that with some people. I'm sure you have those fans that want their nostalgia, and then there are some people who will embrace the newer stuff. Do you find it’s a challenge to reach people with new songs?

Obviously, what we're looking for is, how do we somehow have one foot in the past and one foot into the future? We’ve got the best of all possible worlds because that has been the modus operandi of Billy Idol.

You want to do things that are true to you, and you don't just want to try and do things that you're seeing there in the charts today. I think that we're achieving it with things like "Running From The Ghost" and "Cage" on this new EP. I think we’re managing to do both in a way.

**Obviously, "Running From The Ghost" is about addiction, all the stuff that you went through, and in "Cage" you’re talking about freeing yourself from a lot of personal shackles. Was there any one moment in your life that made you really thought I have to not let this weigh me down anymore?**

I mean, things like the motorcycle accident I had, that was a bit of a wake up call way back. It was 32 years ago. But there were things like that, years ago, that gradually made me think about what I was doing with my life. I didn't want to ruin it, really. I didn't want to throw it away, and it made [me] be less cavalier.

I had to say to myself, about the drugs and stuff, that I've been there and I've done it. There’s no point in carrying on doing it. You couldn't get any higher. You didn't want to throw your life away casually, and I was close to doing that. It took me a bit of time, but then gradually I was able to get control of myself to a certain extent [with] drugs and everything. And I think Steve's done the same thing. We're on a similar path really, which has been great because we're in the same boat in terms of lyrics and stuff.

So a lot of things like that were wake up calls. Even having grandchildren and just watching my daughter enlarging her family and everything; it just makes you really positive about things and want to show a positive side to how you're feeling, about where you're going. We've lived with the demons so long, we've found a way to live with them. We found a way to be at peace with our demons, in a way. Maybe not completely, but certainly to where we’re enjoying what we do and excited about it.

[When writing] "Running From The Ghost" it was easy to go, what was the ghost for us? At one point, we were very drug addicted in the '80s. And Steve in particular is super sober [now]. I mean, I still vape pot and stuff. I don’t know how he’s doing it, but it’s incredible. All I want to be able to do is have a couple of glasses of wine at a restaurant or something. I can do that now.

I think working with people that are super talented, you just feel confident. That is a big reason why you open up and express yourself more because you feel comfortable with what's around you.

Did you watch Danny Boyle's recent Sex Pistols mini-series?

I did, yes.

You had a couple of cameos; well, an actor who portrayed you did. How did you react to it? How accurate do you think it was in portraying that particular time period?

I love Jonesy’s book, I thought his book was incredible. It's probably one of the best bio books really. It was incredible and so open. I was looking forward to that a lot.

It was as if [the show] kind of stayed with Steve [Jones’ memoir] about halfway through, and then departed from it. [John] Lydon, for instance, was never someone I ever saw acting out; he's more like that today. I never saw him do something like jump up in the room and run around going crazy. The only time I saw him ever do that was when they signed the recording deal with Virgin in front of Buckingham Palace. Whereas Sid Vicious was always acting out; he was always doing something in a horrible way or shouting at someone. I don't remember John being like that. I remember him being much more introverted.

But then I watched interviews with some of the actors about coming to grips with the parts they were playing. And they were saying, we knew punk rock happened but just didn't know any of the details. So I thought well, there you go. If ["Pistol" is] informing a lot of people who wouldn't know anything about punk rock, maybe that's what's good about it.

Maybe down the road John Lydon will get the chance to do John's version of the Pistols story. Maybe someone will go a lot deeper into it and it won't be so surface. But maybe you needed this just to get people back in the flow.

We had punk and metal over here in the States, but it feels like England it was legitimately more dangerous. British society was much more rigid.

It never went [as] mega in America. It went big in England. It exploded when the Pistols did that interview with [TV host Bill] Grundy, that lorry truck driver put his boot through his own TV, and all the national papers had "the filth and the fury" [headlines].

We went from being unknown to being known overnight. We waited a year, Generation X. We even told them [record labels] no for nine months to a year. Every record company wanted their own punk rock group. So it went really mega in England, and it affected the whole country – the style, the fashions, everything. I mean, the Ramones were massive in England. Devo had a No. 1 song [in England] with "Satisfaction" in '77. Actually, Devo was as big as or bigger than the Pistols.

You were ahead of the pop-punk thing that happened in the late '90s, and a lot of it became tongue-in-cheek by then. It didn't have the same sense of rebelliousness as the original movement. It was more pop.

It had become a style. There was a famous book in England called Revolt Into Style — and that's what had happened, a revolt that turned into style which then they were able to duplicate in their own way. Even recently, Billie Joe [Armstrong] did his own version of "Gimme Some Truth," the Lennon song we covered way back in 1977.

When we initially were making [punk] music, it hadn't become accepted yet. It was still dangerous and turned into a style that people were used to. We were still breaking barriers.

You have a band called Generation Sex with Steve Jones and Paul Cook. I assume you all have an easier time playing Pistols and Gen X songs together now and not worrying about getting spit on like back in the '70s?

Yeah, definitely. When I got to America I told the group I was putting it together, "No one spits at the audience."

We had five years of being spat on [in the UK], and it was revolting. And they spat at you if they liked you. If they didn't like it they smashed your gear up. One night, I remember I saw blood on my T-shirt, and I think Joe Strummer got meningitis when spit went in his mouth.

You had to go through a lot to become successful, it wasn't like you just kind of got up there and did a couple of gigs. I don't think some young rock bands really get that today.

With punk going so mega in England, we definitely got a leg up. We still had a lot of work to get where we got to, and rightly so because you find out that you need to do that. A lot of groups in the old days would be together three to five years before they ever made a record, and that time is really important. In a way, what was great about punk rock for me was it was very much a learning period. I really learned a lot [about] recording music and being in a group and even writing songs.

Then when I came to America, it was a flow, really. I also really started to know what I wanted Billy Idol to be. It took me a little bit, but I kind of knew what I wanted Billy Idol to be. And even that took a while to let it marinate.

You and Miley Cyrus have developed a good working relationship in the last several years. How do you think her fans have responded to you, and your fans have responded to her?

I think they're into it. It's more the record company that she had didn't really get "Night Crawling"— it was one of the best songs on Plastic Hearts, and I don't think they understood that. They wanted to go with Dua Lipa, they wanted to go with the modern, young acts, and I don't think they realized that that song was resonating with her fans. Which is a shame really because, with Andrew Watt producing, it's a hit song.

But at the same time, I enjoyed doing it. It came out really good and it's very Billy Idol. In fact, I think it’s more Billy Idol than Miley Cyrus. I think it shows you where Andrew Watt was. He was excited about doing a Billy Idol track. She's fun to work with. She’s a really great person and she works at her singing — I watched her rehearsing for the Super Bowl performance she gave. She rehearsed all Saturday morning, all Saturday afternoon, and Sunday morning and it was that afternoon. I have to admire her fortitude. She really cares.

I remember when you went on "Viva La Bam" back in 2005 and decided to give Bam Margera’s Lamborghini a new sunroof by taking a power saw to it. Did he own that car? Was that a rental?

I think it was his car.

Did he get over it later on?

He loved it. [Laughs] He’s got a wacky sense of humor. He’s fantastic, actually. I’m really sorry to see what he's been going through just lately. He's going through a lot, and I wish him the best. He's a fantastic person, and it's a shame that he's struggling so much with his addictions. I know what it's like. It's not easy.

Musically, what is the synergy like with you guys during the past 10 years, doing Kings and Queens of the Underground and this new stuff? What is your working relationship like now in this more sober, older, mature version of you two as opposed to what it was like back in the '80s?

In lots of ways it’s not so different because we always wrote the songs together, we always talked about what we're going to do together. It was just that we were getting high at the same time.We're just not getting [that way now] but we're doing all the same things.

We're still talking about things, still [planning] things:What are we going to do next? How are we going to find new people to work with? We want to find new producers. Let's be a little bit more timely about putting stuff out.That part of our relationship is the same, you know what I mean? That never got affected. We just happened to be overloading in the '80s.

The relationship’s… matured and it's carrying on being fruitful, and I think that's pretty amazing. Really, most people don't get to this place. Usually, they hate each other by now. [Laughs] We also give each other space. We're not stopping each other doing things outside of what we’re working on together. All of that enables us to carry on working together. I love and admire him. I respect him. He's been fantastic. I mean, just standing there on stage with him is always a treat. And he’s got an immensely great sense of humor. I think that's another reason why we can hang together after all this time because we've got the sense of humor to enable us to go forward.

There's a lot of fan reaction videos online, and I noticed a lot of younger women like "Rebel Yell" because, unlike a lot of other '80s alpha male rock tunes, you're talking about satisfying your lover.

It was about my girlfriend at the time, Perri Lister. It was about how great I thought she was, how much I was in love with her, and how great women are, how powerful they are.

It was a bit of a feminist anthem in a weird way. It was all about how relationships can free you and add a lot to your life. It was a cry of love, nothing to do with the Civil War or anything like that. Perri was a big part of my life, a big part of being Billy Idol. I wanted to write about it. I'm glad that's the effect.

Is there something you hope people get out of the songs you've been doing over the last 10 years? Do you find yourself putting out a message that keeps repeating?

Well, I suppose, if anything, is that you can come to terms with your life, you can keep a hold of it. You can work your dreams into reality in a way and, look, a million years later, still be enjoying it.

The only reason I'm singing about getting out of the cage is because I kicked out of the cage years ago. I joined Generation X when I said to my parents, "I'm leaving university, and I'm joining a punk rock group." And they didn't even know what a punk rock group was. Years ago, I’d write things for myself that put me on this path, so that maybe in 2022 I could sing something like "Cage" and be owning this territory and really having a good time. This is the life I wanted.

The original UK punk movement challenged societal norms. Despite all the craziness going on throughout the world, it seems like a lot of modern rock bands are afraid to do what you guys were doing. Do you think we'll see a shift in that?

Yeah. Art usually reacts to things, so I would think eventually there will be a massive reaction to the pop music that’s taken over — the middle of the road music, and then this kind of right wing politics. There will be a massive reaction if there's not already one. I don’t know where it will come from exactly. You never know who's gonna do [it].