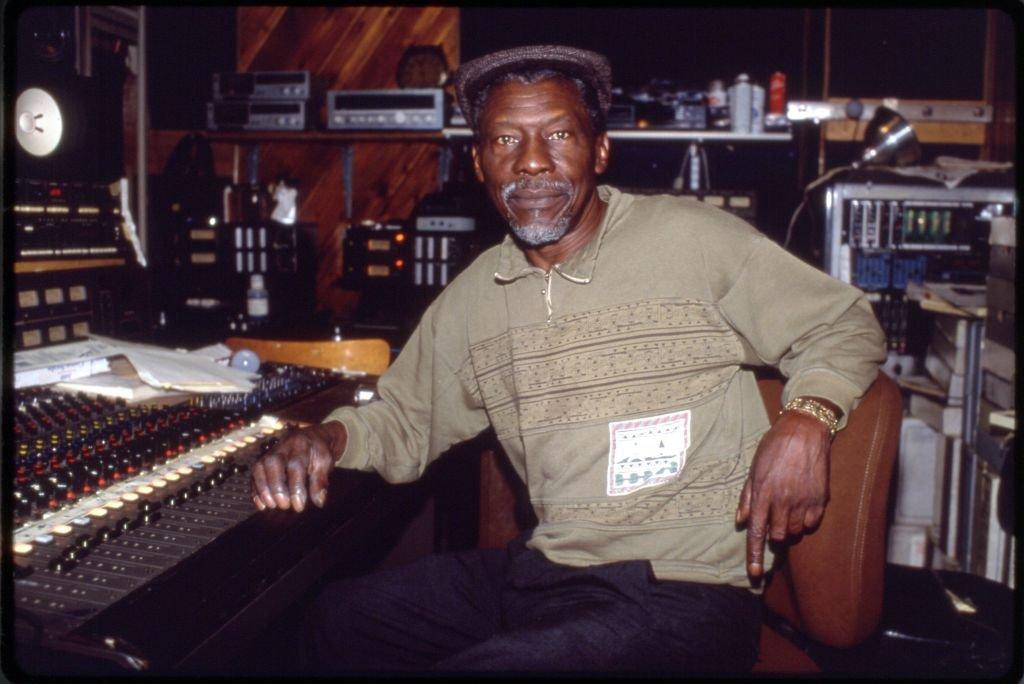

On April 30, 2004, producer Clement Seymour "Sir Coxsone" Dodd — an architect in the construction of Jamaica’s recording industry — was honored at a festive street renaming ceremony on Brentford Road in Kingston, Jamaica. The bustling, commercial thoroughfare at the geographical center of Kingston was rechristened Studio One Blvd. in recognition of Coxsone’s recording studio and record label.

Dodd is said to have acquired a former nightclub at 13 Brentford Road in 1962; his father, a construction worker, helped him transform the building into the landmark studio. In 1963 Dodd installed a one-track board and began recording and issuing records on the Studio One label.

Dodd’s Studio One was Jamaica’s first Black-owned recording facility and is regarded as Jamaica’s Motown because of its consistent output of hit records. Studio One releases helped launch the careers of numerous ska, rocksteady and reggae legends including Bob Andy, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, the Gladiators, the Skatalites, Toots and the Maytals, Marcia Griffiths, Sugar Minott, Delroy Wilson and most notably, the Wailers.

At the street renaming ceremony, a jazz band played, speeches were given in tribute to Dodd’s immeasurable contributions to Jamaican music and many heartfelt memories from the studio’s heyday were shared. In the culmination of the late afternoon program, Dodd, his wife Norma, and Kingston’s then mayor Desmond McKenzie unveiled the first sign bearing the name Studio One Blvd. Four days later, on April 4, 2002, Coxsone Dodd suffered a fatal heart attack at Studio One. His productions, however, live on as benchmarks within the island’s voluminous and influential music canon.

Born Clement Seymour Dodd on Jan. 26, 1932, he was given the nickname Sir Coxsone after the star British cricketer whose batting skills Clement was said to match. As a teenager, Dodd developed a fondness for jazz and bebop that he heard beamed into Jamaica from stations in Miami and Nashville and the big band dances he attended in Kingston. Dodd launched Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat sound system around 1952 with the impressive collection of R&B and jazz discs he amassed while living in the U.S., working as a seasonal farm laborer.

Many sound system proprietors traveled to the U.S. to purchase R&B records — the preferred music among their dance patrons and key to a sound system’s following and trumping an opponent in a sound clash. With the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, suitable R&B records became scarce. Jamaica’s ever-resourceful sound men ventured into Kingston studios to produce R&B shuffle recordings for sound system play.

Recognizing there was a wider market for this music, Dodd pressed up a few hundred copies of two sound system favorites for general release, the instrumental "Shuffling Jug" by bassist Cluett Johnson and his Blues Blasters and singer/pianist Theophilus Beckford’s "Easy Snapping," both issued on Dodd’s first label, Worldisc. (Some historians recognize "Easy Snapping" as a bridge between R&B shuffle and the island’s Indigenous ska beat; others cite it as the first ska record.) When those discs sold out within a few days, other soundmen followed Dodd’s lead and Jamaica’s commercial recording industry began to flourish.

"Before then, the only stuff released commercially were mento records that were recorded here, but our sound really hit so we kept on recording. When I heard 'Easy Snapping,' I said 'Oh my gosh!'" Coxsone recalled in a 2002 interview for Air Jamaica's Skywritings at Kiingston’s Studio One. "I thank God for that moment."

Dodd was the first producer to enlist a house band, pay them a weekly salary rather than per record. Together, they had an impressive run of hits in the ska era in the early ‘60s; during the rocksteady period later in the decade, Dodd ceded top ranking status to long standing sound system rival (but close family friend) turned producer Duke Reid. (Still, Studio One released the most enduring instrumentals or rhythm tracks, also known as riddims, of the period.) As rocksteady morphed into reggae circa 1968, Dodd triumphed again with consistent releases of exceptional quality.

In 1979 armed robbers targeted the Brentford Rd premises several times. Dodd left Jamaica and established Coxsone’s Music City record store/recording studio in Brooklyn, dividing his time between New York and Kingston. Reissues of Dodd’s music via Cambridge, MA based Heartbeat Records, beginning in the mid 1980s, followed by London’s Soul Jazz label in the 2000s, and most recently Yep Roc Records in Hillsborough, NC, have helped introduce Studio One’s masterful work to new generations of fans.

"The best time I’ve ever had was when I acquired my studio at 13 Brentford Rd. because you can do as many takes until we figured that was it," Coxsone reflected in the 2002 interview. "God gave me a gift of having the musicians inside the studio to put the songs together. In the studio, I always thought about the fans, making the music more pleasing for listening or dancing. What really helped me was having the sound system, you play a record, and you weren’t guessing what you were doing, you saw what you were doing."

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of Coxsone Dodd’s passing, read on for a list of 10 of his greatest productions.

The Maytals - "Six and Seven Books of Moses" (1963)

In 1961 at the dawn of Jamaica’s ska era, Toots Hibbert met singers Nathaniel "Jerry" Matthias and Henry "Raleigh" Gordon and they formed the Maytals. The trio released several hits for Dodd including the rousing, "Six and Seven Books of Moses," a gospel-drenched ska track that’s essentially a shout out of a few Old Testament chapters.

Moses is credited with writing five chapters, as the lyrics state, "Genesis and Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers Deuteronomy," but "the Six and Seven books" are in question. Many Biblical scholars say Moses wasn’t the scribe, believing those chapters, including phony spells and incantations to keep evil spirits away, were penned in the 18th or 19th century.

Nevertheless, there’s a real magic formula in The Maytals’ "Six and Seven Books of Moses": Toots’ electrifying preacher at the pulpit delivery melds with elements of vintage soul, gritty R&B, and classic country; Jerry and Raleigh provide exuberant backing vocals and seminal ska outfit and Studio One’s first house band, the Skatalities deliver an irresistible, jaunty ska rhythm with a sophisticated jazz underpinning.

The Wailers - "Simmer Down" (1964)

A flashback scene in the biopic Bob Marley: One Love depicts the Wailers (then a teenaged outfit called the Juveniles) approaching Dodd for a recording opportunity; Dodd inexplicably points a gun at them as they recoil in terror. Yet, there isn’t any mention of such an inappropriate and unprovoked action from the producer in the various books, documentaries, interviews and other accounts of the Wailers’ audition for Dodd.

The Wailers’ first recording session with Dodd in July 1964, however, yielded the group’s first hit single "Simmer Down." At that time, the Wailers lineup consisted of founding members Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston (later Wailer) and Peter Tosh alongside singers Junior Braithwaite and (the sole surviving member) Beverley Kelso. When Junior left for the U.S., Dodd appointed Marley as the group’s lead singer.

The energetic "Simmer Down" cautions the impetuous rude boys to refrain from their hooligan exploits. The Skatalites’ spirited horn led intro, thumping jazz infused bass and fluttering sax solo, enhances Marley’s youthful lead and the backing vocalists’ effervescence. The Wailers would spend two years at Studio One and record over 100 songs there, including the first recording of "One Love" in 1965; by early 1966, they would have five songs produced by Dodd in the Jamaica Top 10.

Alton Ellis -"I’m Still In Love" (1967)

Jamaica’s brief rocksteady lasted about two years between 1966-1968, but was an exceptionally rich and influential musical era. The rocksteady tempo maintained the accentuated offbeat of its ska predecessor, but its slower pace allowed vocal and musical arrangements, affixed in heavier, more melodic basslines.

Alton Ellis is considered the godfather of rocksteady because he had numerous hits during the era and released "Rock Steady," the first single to utilize the term for producer Duke Reid. Ellis initially worked with Dodd in the late 1950s then returned to him in 1967. The evergreen "I’m Still in Love" was penned by Alton as a plea to his wife as their marriage dissolved: "You don’t know how to love me, or even how to kiss me/I don’t know why." Supporting Alton’s elegant, soulful rendering of heartbreak, Studio One house band the Soul Vendors, led by keyboardist Jackie Mittoo, provide an engaging horn-drenched rhythm, epitomizing what was so special about this short-lived time in Jamaican music.

"I’m Still In Love" has been covered by various artists including Sean Paul and Sasha, whose rendition reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2004. Beyoncé utilized Jamaican singer Marcia’s Aitken’s 1978 version of the tune in a TV ad announcing her 2018 On The Run II tour with Jay-Z. In February 2024, Jennifer Lopez sampled "I’m Still in Love" for her single "Can’t Get Enough."

Bob Andy - "I’ve Got to Go Back Home" (1967)

The late Keith Anderson, known professionally as Bob Andy, arrived at Studio One in 1967. He quickly became a hit-making vocalist, and an invaluable writer for other artists on the label. He penned several hits for Marcia Griffiths including "Feel Like Jumping," "Melody Life" and "Always Together," the latter their first of many hit recordings as a duo.

A founding member of the vocal trio the Paragons, "I’ve Got to go Back Home" was Andy’s first solo hit and it features sublime backing vocals by the Wailers (Bunny, Peter and Constantine "Vision" Walker; Bob Marley was living in the USA at the time.) Set to a sprightly rock steady beat featuring Bobby Ellis (trumpet), Roland Alphonso (saxophone) and Carlton Samuels’ (saxophone) harmonizing horns, Andy’s lyrics poignantly depict the challenges endured by Jamaica’s poor ("I can’t get no clothes to wear, can’t get no food to eat, I can’t get a job to get bread") while expressing a longing to return to Africa, a central theme within 1970s Rasta roots reggae.

The depth of Andy’s lyrics expanded the considerations of Jamaican songwriters and one of his primary influences was Bob Dylan. "When I heard Bob Dylan, it occurred to me for the first time that you don’t have to write songs about heart and soul," Andy told Billboard in 2018. "Bob Dylan’s music introduced me to the world of social commentary and that set me on my way as a writer."

Dawn Penn - "You Don’t Love Me" (1967)

Dawn Penn’s plaintive, almost trancelike vocals and the lilting rock steady arrangement by the Soul Vendors transformed Willie Cobbs’ early R&B hit "You Don’t Love Me," based on Bo Diddley’s 1955 gritty blues lament "She’s Fine, She’s Mine," into a Jamaican classic. The song’s shimmering guitar intro gives way to the forceful drum and bass with Mittoo’s keyboards providing an understated yet essential flourish.

In 1992 Jamaica’s Steely and Clevie remade the song, featuring Penn, for their album Steely and Clevie Play Studio One Vintage. The dynamic musician/production duo brought their mastery (and 1990s technological innovations) to several Studio One classics with the original singers. Heartbeat released "You Don’t Love Me" as a single and it reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Several artists have reworked Penn’s rendition or sampled the Soul Vendors’ arrangement including rapper Eve on a collaboration with Stephen and Damian Marley. Rihanna recruited Vybz Kartel for an interpretation included on her 2005 debut album Music of the Sun, while Beyoncé performed the song on her I Am world tour in 2014 and recorded it in 2019 for her Homecoming: The Live Album. In 2013, Los Angeles-based Latin soul group the Boogaloo Assassins brought a salsa flavor to Penn's tune, creating a sought-after DJ single.

The Heptones - "Equal Rights" (1968)

"Every man has an equal right to live and be free/no matter what color, class or race he may be," sings an impassioned Leroy Sibbles on "Equal Rights," the Heptones’ stirring plea for justice.

Harmony vocalist Earl Morgan formed the group with singer Barry Llewellyn in the early '60s and Sibbles joined them a few years later. The swinging bass line, played by Sibbles, anchors a stunning rock steady rhythm track awash in cascading horns, and blistering percussion patterns akin to the akete or buru drums heard at Rastafari Nyabinghi sessions.

Besides leading the Heptones’ numerous hit singles during their five-year stint at Studio One, Sibbles was a talent scout, backing vocalist, resident bassist and the primary arranger, alongside Jackie Mittoo. Sibbles’ progressive basslines are featured on numerous Studio One nuggets (many appearing on this list) and have been sampled or remade countless times over the decades on Jamaican and international hits.

In a December 2023 interview Sibbles echoed a complaint expressed by many who worked at Studio One: Dodd didn’t fairly compensate his artists and the (uncredited) musicians produced the songs while Dodd tended to business matters. "When we started out, we didn’t know about the business, and what happened, happened. But as you learn as you go along," he said. "I have registered what I could; I am living comfortably so I am grateful."

The Cables - "Baby Why" (1968)

Formed in 1962 by lead singer Keble Drummond and backing vocalists Vincent Stoddart and Elbert Stewart, the Cables — while not as well-known as the Wailers, the Maytals or the Heptones — recorded a few evergreen hits at Studio One, including the enchanting "Baby Why."

Keble’s aching vocals lead this breakup tale as he warns the woman who left that she’ll soon regret it. The simple story line is delivered via a gorgeous melody that’s further embellished by Vincent and Elbert’s superb harmonizing, repeatedly cooing to hypnotic effect "why, why oh, why?"

Coxsone is said to have kept the song for exclusive sound system play for several months; when he finally released it commercially, "Baby Why" stayed at No. 1 for four weeks.

"Baby Why" is notable for another reason: although the Maytals’ "Do The Reggay" marks the initial use of the word reggae in a song, "Baby Why" is among a handful of songs cited as the first recorded with a reggae rhythm (reggae basslines are fuller and reggae’s tempo is a bit slower than its rocksteady forerunner.) Other contenders for that historic designation include Lee "Scratch Perry’s "People Funny Boy," the Beltones’ "No More Heartache," and Larry Marshall and Alvin Leslie’s delightful "Nanny Goat."

Burning Spear - "Door Peeper" (1969)

Hailing from the parish of St. Ann, Jamaica, Burning Spear was referred to Studio One by another St. Ann native, Bob Marley. Spear’s first single for Studio One "Door Peeper" (also known as "Door Peep Shall Not Enter") recorded in 1969, sounded unlike any music released by Dodd and was critical in shaping the Rastafarian roots reggae movement of the next decade.

The song’s biblically laced lyrics caution informers who attempt to interfere with Rastafarians, considered societal outcasts at the time in Jamaica, while Spear’s intonation to "chant down Babylon" creates a haunting mystical effect, supported by Rupert Willington’s evocative, deep vocal pitch, a throbbing bass, mesmeric percussion and magnificent horn blasts.

As Spear told GRAMMY.com in September 2023, "When Mr. Dodd first heard 'Door Peep' he was astonished; for a man who’d been in the music business for so long, he never heard anything like that." Dodd’s openness to recording Rasta music, and allowing ganja smoking on the premises (but not in the studio) when his competitors didn’t put him in the forefront at the threshold of the roots reggae era.

"Door Peeper" was included on Burning Spear’s debut album, Studio One Presents Burning Spear, released in 1973 and remains a popular selection in the legendary artist’s live sets.

Joseph Hill - "Behold The Land" (1972)

In the October 1946 address Behold The Land by W. E. B. DuBois at the closing session of the Southern Youth Legislature in Columbia, South Carolina, the then 78-year-old celebrated author and activist urges Black youth to fight for racial equality and the civil rights denied them in Southern states. The late Joseph Hill’s 1972 song of the same name, possibly influenced by Dubois’ words, is a powerful reggae missive exploring the atrocities of the transatlantic slave trade from which descended the discriminations DuBois described.

Hill was just 23 when he wrote/recorded "Behold The Land," his debut single as a vocalist. Hill’s haunting timbre summons the harrowing experience with the wisdom and emotional rendering of an ancestor: "For we were brought here in captivity, bound in links and chains and we worked as slaves and they lashed us hard." Hill then gives praise and asks for repatriation to the African motherland, "let us behold the land where we belong."

The Soul Defenders — a self contained entity but also a Studio One house band with whom Hill made his initial recordings as a percussionist — provide a persistent, bass heavy rhythm that suitably frames Hill’s lyrical gravitas, as do the melancholy hi-pitched harmonies.

In 1976 Hill formed the reggae trio Culture and the next year they catapulted to international fame with their apocalyptic single "Two Sevens Clash," which prompted Dodd to finally release "Behold The Land." Culture would re-record "Behold The Land" over the years including for their 1978 album Africa Stand Alone and the song received a digital remastering in 2001.

Sugar Minott - "Oh Mr. DC" (1978)

In the mid-1970s singer Lincoln "Sugar" Minott began writing lyrics to classic 1960s Studio One riddims, an approach that launched his hitmaking solo career and further popularized the practice of riddim recycling — which is still a standard approach in dancehall production. Sugar, formerly with the vocal trio The African Brothers, penned one of his earliest solo hits "Oh, Mr. DC" to the lively beat of the Tennors’ 1967 single "Pressure and Slide" (itself a riddim originally heard, at a faster pace, underpinning Prince Buster’s 1966 "Shaking Up Orange St.")

"Oh, Mr. DC" is an authentic tale of a ganja dealer returning from the country with his bag of collie (marijuana); the DC (district constable/policeman) says he’s going to arrest him and threatens to shoot if he attempts to run away. Sugar explains to the officer that selling herb is how he supports his family: "The children crying for hunger/ I man a suffer, so you’ve got to see/it’s just collie that feed me." To underscore his urgent plea, Sugar wails in an unforgettable melody, "Oh, oh DC, don’t take my collie."

The irresistibly bubbling bassline of the riddim nearly obscures the song’s poignant depiction of Jamaica’s harsh economic realities and the potential risk of imprisonment, or worse, that the island’s ganja sellers faced at the time. Sugar’s revival of a Studio One riddim and reutilization of 10 Studio One riddims for each track of his 1977 album Live Loving brought renewed interest to the treasures that could be extracted from Mr. Dodd’s vaults.

Special thanks to Coxsone Dodd’s niece Maxine Stowe, former A&R at Sony/Columbia and Island Records, who started her career at Coxsone’s Music City, Brooklyn.

How 'The Harder They Come' Brought Reggae To The World: A Song By Song Soundtrack Breakdown