Peter Gabriel's first two albums are full of brilliant moments: the cinematic 7/8 saunter of "Solsbury Hill," the spooky art-funk atmospheres of "Exposure," the creepy-crawly grooves on "Moribund the Burgermeister." But they showcased a songwriter searching for an identity, working with famous producers (Bob Ezrin on his 1977 debut, King Crimson's Robert Fripp on his 1978 follow-up) and exploring new sounds on each song—seemingly to find one that might stick.

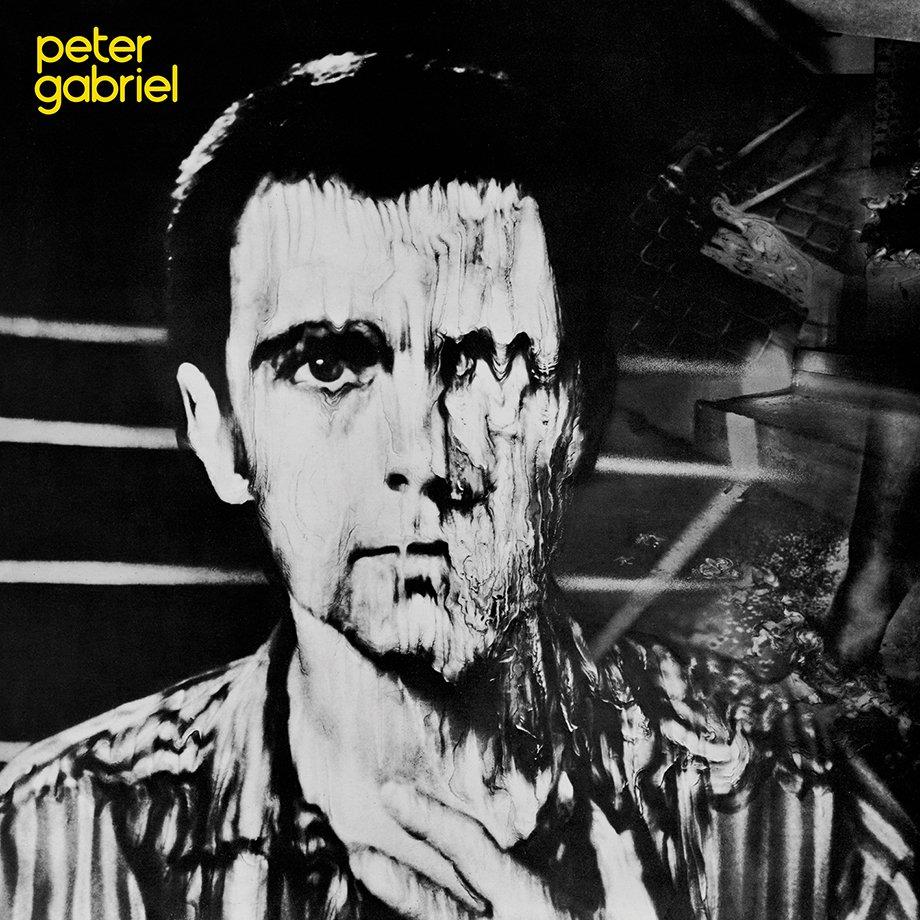

That moment arrived in 1980 with his third solo project, another self-titled set best-known by its lavish, Hipgnosis-designed cover art. (In this case, the image of Gabriel's half-disintegrated face earned the nickname "Melt.") Working with producer Steve Lillywhite, producer Hugh Padgham, synth player Larry Fast, drummer Jerry Marotta and a tightly knit ensemble of other players, he crafted a sonic space that, four decades later, remains distinctly his: Songs like "Games Without Frontiers," "No Self Control" and "I Don't Remember" fuse bleak, paranoid lyrics with expansive arrangements (loads of marimba and saxophone) and production techniques that somehow still sound modern.

40 years later, Gabriel's key collaborators reflect on the studio experimentation, happy accidents and deep friendships that fueled an art-rock masterpiece.

Gabriel had a background in progressive rock—a very uncool movement in the era of punk and New Wave. So Lillywhite, who cut his teeth working with hip, edgy bands like XTC and Siouxsie and the Banshees, was shocked the former Genesis frontman would be interested in collaborating.

Steve Lillywhite, producer: Up until that point, I'd worked with these New Wave bands [like XTC], and Peter was the first artist who came to me. His manager actually phoned me up and said, "Steve, Peter Gabriel is interested in you working with him." I thought it was a friend of mine joking! I thought it was someone winding me up.

I remember Peter in Genesis wearing a [fox's] head [onstage], and that was really not cool. And, of course, we all knew he was a public school boy, which made it not very Joe Strummer. [Laughs.] I'd produced XTC's [1979 album] Drums and Wires [with Hugh Padgham as engineer]. Peter heard "Making Plans for Nigel" or something and liked what he heard.

Hugh Padgham, engineer: Steve and I had really hit it off and become friendly. [Drums and Wires] was very well critiqued, and I think that's where Peter had heard of us, particularly Steve. Peter's manager at that time was Gail Colson, and she got ahold of Steve, and Steve said to me, "You won't believe it—I've been asked if I'm interested in working with Peter Gabriel. What do you reckon?" I was a huge Genesis fan. I had some friends who went to the same school as Peter, Charterhouse. The original drummer in Genesis, John Silver, went to the public school I went to. We all sort of thought Genesis was our own band in a way. For me to end up with Peter—and after that end up working with Phil Collins and Genesis—I was, as you can imagine, like a pig in shit. [Laughs.]

Steve accepted the offer, and we were all very excited. We started off recording it using a mobile recording studio owned by Virgin Records called the Manor Mobile. At that point, the Townhouse [studio, where Padgham was house engineer] was brand new. We went down to Ashcombe House, where Peter lived near Bath, England and started the recording there with this mobile truck. Ashcombe had a barn that we did the recording in. I remember it was muddy and rainy. It's a hazy memory, but that must have been the first place I met Peter.

Gabriel's production team was, indeed, brand new—as were some of the album's core musicians (including guitarist David Rhodes, who became a staple of Gabriel's future creative team). But two of the record's most essential performers, synthesizer/processing wizard Larry Fast and drummer Jerry Marotta, were already members of his touring and studio band.

Jerry Marotta, drummer: Peter was a band guy. He'd been in Genesis. I don't think he had much experience with musicians. I never figured out [why Gabriel recruited him]—maybe [bassist/Chapman Stick player] Tony Levin had something to do with it. I don't think it mattered once we got past the first date stage. We just got along well, and it was a good working situation.

Larry Fast, synthesizer player: We'd already encountered each other way back, going back to the early Genesis tours. I did have the first two Synergy [solo] albums under my belt, and those were the days when an electronic instrumental album could chart pretty high as well. [Laughs.] Obviously Peter is more interested in creativity and artistic sentiments than somebody who did well on the charts. We had some overlaps: The label I was signed to, Jem Records, was very instrumental in breaking Genesis in the U.S. through import records. They were fundamentally important to making sure the band got heard because the distributing label Charisma had early on—I don't think they knew what to do with the band. That led to meeting not only with the band members and getting to know Peter a bit, but also the management group for Hit and Run, which would be handling Peter in his solo career as well as Genesis when he left the band. I had a lot of encounters there. I was already beginning to tour as an adjunct member of [prog-rock band] Nektar at that point.

Gabriel's core studio team also included bassist John Giblin (subbing in for regular low-end master, Tony Levin, who was busy filming the Paul Simon movie One-Trick Pony), percussionist Morris Pert and his old Genesis bandmate Phil Collins, who played drums on a few cuts. (More on that later.) And for Gabriel, a dark and innovative sonic vision was starting to crystalize around these versatile players.

Fast: Some of it is an exploration of what the possibilities might be, but he'd explored the ground already with his first two albums. They were really good records in their own way, but there were [other] ideas I heard Peter speak about: We sat down before the first album, and we had a nice meal and talked through a lot of conceptual possibilities. One of the things he mentioned was the idea of no cymbals, which I thought was terrific. It's exactly the way I'd been working in electronic music, particularly in the pre-sampling days. There were no cymbals, and they eat up a lot of sonic space. Peter had speaking about wanting to do that on the first album, but it didn't materialize. I suppose somewhere in conversations that came up and was nixed. Moving on to album two, I don't know if he brought it up again, but same deal: another strong-minded producer in Robert Fripp with a sound of his own. Cymbals were there.

Both Steve Lillywhite and Hugh Padgham were perhaps a little down lower in the hierarchy than a Robert Fripp or a Bob Ezrin, and Peter had had some success under his belt, and they were creative enough to say, "He's the artist. He's the creative one. Maybe we should try some of this." It stuck. And it was a great idea.

Lillywhite: Peter did not want to be complacent on this album. When we met, I said, "What sort of sound do you want on this album?" Right away, he was like, "I don't want cymbals." For me, it was like, "Oh, my god." I'd been starting to experiment with no cymbals on songs. But sometimes I would overdub cymbals because of the sounds I was looking for.

Padgham: I remember distinctly that was rule number one from the beginning: There was gonna be no cymbals on the record. I can't remember any other particular rules. From a rock point of view and a drummer's point of view, it's like cutting off half their arms to ask a drummer not to play cymbals or hi-hats. It was probably quite difficult.

Phil [Collins, who appears on a few songs] sort of took it very much in his stride. Phil is mister fanatically keen, especially in those days. I think Jerry probably found it harder. If I remember, we set up fake cymbals or bits of cardboard or something just so it didn't appear so weird to him.

Marotta: It took me awhile to get used to the fact that I couldn't hit a cymbal when I played something. At the very most, I may have thought, "This is nuts and it's not gonna work." Take the cymbals away and in time, someone will see, "We've gotta put some cymbals back up." But I became very comfortable with that very quickly. I don't remember the moment I got it, but I just got it. I'm obsessive-compulsive, and I have an addictive personality, so if I start doing something, I'm doing it all the time.

I didn't invent that [idea], but I sure did it more and more—to the point where people would get weirded out [in sessions]. When I was playing on other people's records, they'd be like, "Hey man, do you think you can hit a cymbal occasionally?" But who says you have to crash a cymbal at the end of every fill or going into the chorus? Who came up with that concept?

A vibe was emerging: heavy rhythms, experimental effects, heavily processed synthesizers, dark lyrical imagery. But Gabriel, a very un-prolific songwriter, didn't have all his songs finished when the sessions began.

Fast: Most of the songs were somewhat defined, at least the instrumental tracks, and that goes back to the first album. The working mode would be that we'd go into the studio for the day, and all the musicians would gather in a little room off the main studio, and Peter would sit down at the piano with all of us clustered around with clipboards and notebooks and music paper on our laps and play through what the song was going to be. Often the lyrics weren't completely formed yet, but he'd know where he wanted the chorus, what the melody was going to be, but he was working out the poetry of the song in some cases. That didn't really change. The only difference, by the third album, Peter had already created the drum machine and quick multi-track eversions of these things on cassette. I'd come over for the rhythm tracks after the other guys were already cutting them, and I already had a cassette of about 14 or 16 potential songs for the record. I was familiar with what they'd be, but they'd be recut with the musicians to create the backbone or spine of the song.

There were a couple [songs] that were the beginning of Peter using a drum box. That was something I had. It was a small synthesizer kit company called PAiA, and that was actually owned and founded by a friend of mine who's another synthesizer designer. They had a kit that, to the best of my knowledge, was the first programmable drum box. All the ones prior to that, they were really intended for lounge music and things, so there would be a button you'd push for a cha-cha rhythm or a foxtrot rhythm. It was an accompanist box. Some of them were so corny and square that they were kinda hip in their own way. But [programmable beats] didn't exist until this little PAiA box.

They were electronically generated drum sounds, but it had computer memory in it. You'd push a button and get the metronome tick, and you'd play your drum part and hit the stop button, and it would loop it and remember the drum pattern. It was very small—about the size of a cigar box—and inexpensive. I got one just to play with during the scened album, and Peter became aware of it around the time the second album was finished. He was enthralled with it. [Fast reached out to the company and had them custom-build one for Gabriel.] I remember bringing it to Peter, and about six or eight months later, when the third album cassette tracks were showing up, there was the box used as the spine of a lot of tracks. For Peter, it was a real creative breakthrough because things started being based more on the rhythm.

After their early sessions in Bath, the crew moved into the residential Townhouse studio in London, where their experiments—encouraged and often facilitated by the team of Lillywhite, Padgham and Fast—continued through the album's completion.

Padgham: We were trying to be really experimental. One of the staff had just had a baby or something, and she brought it in one day to show off to everybody. And we said, "Can we borrow your baby for a bit?" We brought the baby in the studio, and it started crying because it was missing its mum, and we were recording it. We slowed the tape down so that it sounded like an old man crying. Then we distorted it and stuff like that. We were doing weird, experimental shit.

Fast: What was really important with Steve and Hugh is they could facilitate Peter's ideas—they could gently point out, as many of us would when something wasn't so practical. But sometimes radical thinking: It's not like doing surgery; it's making records. So why not try it? Why not try to be creative? They gave Peter the space to be Peter. That was so important, and they were also able to help him make an idea even better. The third one was where Peter really hit his stride.

Lillywhite: Peter was enjoying the energy of what we were doing. If we took it to five, he'd say, "No, push it to 10." It was a real art school project.

Of course, the most iconic experiments—the gated drum sound on "Intruder"—helps the album endure as what Lillywhite calls a "sonic flagpole."

The short version: Studio Two at the Townhouse featured a recording console from a new company, Solid State Logic (or SSL), offering compressors and noise gates on every channel. They also featured a "reverse talkback mic," which allowed easier communication between the engineers/producers in the control room and the musicians in the live room. One day, Padgham accidentally—or perhaps by fate—opened the talkback mic at the precise moment Collins was tuning his drums before a session. The sound—a fast shutdown of the drum's natural decay—offered a distinct punch that eventually became one of the defining production techniques of the 1980s. Collins famously utilized the sound on his 1981 solo debut, Face Value, which Padgham engineered and co-produced.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/vAzUh_H7yV0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Padgham: We heard this incredible sound suddenly coming through our loud speakers in the control room. The reverse talkback mic circuit had a very, very heavy compressor on it. The effect was remarkable on the sound of the drum that came through. I think we were all in the control room together: Peter, Steve, me, Larry Fast probably, and whoever else. And everybody just went, "Wow, that's bloody incredible!"

Fast: I missed school that day. [Laughs.]

Unfortunately, the reverse talkback mic was rooted to the monitors, not the console, meaning there was no way of recording this jarring sound. Padgham came to the rescue, having the studio's maintenance engineers figure out a workaround in the console.

Padgham: Just for kicks, I went, "Let's see if we can compress it even more." The same button that turned the compressor on effectively turned the noise gate on as well. The noise gate under a certain threshold would cut it off before the decay finished. That's where we all went "wow" again where the sound suddenly shut off. You had this enormous sound, and suddenly it shut off to nothing.

Lillywhite: When the drummer was drumming and we'd put on the talkback mic to talk to him while he was still drumming, it sounded like the best drum sound ever because of the compression on the talkback mic. We got Hugh to plug that talkback mic into the desk. Like I said, if we said we wanted to take it to five, Peter would say, "Take it to 10."

Padgham: Phil came up with a drum part that would enable us to hear the sound shutting off as he was playing. If you play something too quickly, the noise gate never had time to shut off. It would just be open the whole time. In those days, because we didn't have any looping—nothing was digital at all. The only way of him playing in time so it would consistently shut off was to play to a metronome—a good, old-fashioned metronome. We found a tempo that worked, put it into Phil's headphones, he played the drum pattern that worked with all the closing noise gates for about seven or eight minutes, and Peter wrote the song around it.

Lillywhite: In those days, Phil was as good a drummer as anyone in the world. The fact that he can do something like "Intruder," which is so metronomic. That's what I love about Phil as a drummer. There are some great drummers in the world: [Dave Matthews Band's] Carter Beauford is a fantastic drummer, but there's one thing Carter can't do: Carter cannot be Ringo, whereas Phil Collins can be Carter Beauford but also Ringo.

Padgham: It's basically a story of happy accidents. Steve was there, Phil was there, Peter was there. We all sort of took the credit for it, I suppose. It doesn't matter who invented it or didn't invent [the sound].

One of the record's most rewarding experiments came on the dynamic, unnerving "No Self Control," which they built by subtraction rather than addition. The song featured a winding arrangement—inspired in part by Steve Reich—full of eerie Kate Bush backing vocals, steady layers of marimba and highly processed vocals.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/3yEcTB2va5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Lillywhite: That song originally had drums and everything—every sound you hear at any point—on the multi-track all the way through. When we mixed it, we sculpted it. It was like, "Let's take as much out as we can to make it sound good at the beginning." So we took everything out and left just the marimba and Phil Collins' live bass drum, which we gated so you couldn't hear the rest of the drum kit. [Laughs.] We did about 20 or 30 seconds of the song at a time, with Hugh Padgham at the back of the control room with his headphones on, editing it to the bit before. But we never listened to it—we just trusted him that he did the edit right. I sat at the mixing desk getting the next bit, going, "OK, what should we do now? Let's do this. Let's bring in that." I remember we spent the whole night doing the mix. For the big playback at the end, we brought people in from outside because we knew we had something great. It was like a sculpture. The whole time we recorded it, it had been this big, solid rock. It absolutely came to its beauty in the mix. It was fantastic. Everyone who listened to it was like, "Oh, my god." That was the song everyone loved, loved, loved at the time.

Many of the song's interesting effects were created using the "$9.95" speaker, dubbed as such by the band because Fast purchased it for that price at Radio Shack.

Fast: Radio Shack made a little box—it was basically a transistor radio that had no tuner in it. So it was just a little tiny speaker, a little nine-volt battery, a volume control and an input jack. I could just plug that into anywhere on the modular synth, turn it on quietly in the control room and put it up to one ear like a single-sided headset. I would also use it to set my delay times, reverb depths and other things while waiting to do an overdub so I wouldn't be wasting time. Studio time was expensive! I was doing some processing on Peter's vocals on something, and I had it plugged into the output of something, and Peter's vocals were coming in through a Moog filter or something. They said, "What do you got?" I turned it up, and it was all distorted and horrible-sounding. Peter went, "I love that! Let's use that! Let's put a microphone on it!" I said, "We'll plug it into the board and clean it all up.' He went, "No, no, no!"

Lillywhite: Every single sound on "No Self Control" at the very beginning is the $9.95. Larry used to sit at the back of the control room, working on sounds. He would say, "Check this out, guys." We'd listen to it though the speaker and go, "That's good." Then we'd plug it into the mixing desk, and it sounded average and boring. It was this plastic distortion. On "No Self Control," Peter held the $9.95 up to his mouth, him moving his mouth [makes wah-wah noise] with a microphone there. It was a bit like a poor man's Peter Frampton or something. Peter was holding the thing there, and we retreated it. All the [mouth sounds] is the $9.95. It was the cheapest speaker you've ever heard, but it had this beautiful analog distortion just from the plastic of the speaker.

Fast: We used it a lot. It got really beat up. It was in a little plastic case that fell on the floor a bunch of times. It was held together with gaffer tape. I have it preserved—it's like an archived item. It doesn't get used anymore. I bought another one after that album because the other one was getting too beat up. We processed vocals, synth lines, even drum things. It was exactly like that same thing with the cymbals: How do we conserve sonic space while creating a big sound?

Pictured: Fairlight CMI co-developer Peter Vogel in the Manor Mobile with the prototype of the digital synthesizer/sampler used on 'PG III.'

Photo courtesy of Larry Fast

The third Gabriel album didn't have any singles in the commercial stratosphere of "Sledgehammer," but it did spawn a few minor hits, including the chilly, electronic "Jeux San Frontieres," which landed at Number Four on the U.K. charts. That song also featured a memorable backing vocal ("Jeux sans frontières": the song title in French) from a kindred creative spirit, Kate Bush.

Fast: It's based on the "Jeux San Frontieres" TV show, this multi-national game show competition. Instead of war from these various countries, many of which had been combatants during WWII, they would just have games for national pride. So they're "games without frontiers and war without tears." It all factors in. But Peter was drawing these analogies between the shooting wars and the kind of games that are in the words.

I was reading a book in the studio: Michael Herr's Dispatches, which was one of the first reexaminations of how ugly the Vietnam War had been. Peter was fascinated by it, and I don't know if he bought a copy or borrowed my copy, but a couple of the images showed up. One of the most vivid ones was an American G.I. pissing on a dead Vietnamese soldier. And it was a reflection of, "What have we become as Americans that that could happen?" That image found its way into the lyrics, except Peter used "goons in the jungle" instead of [the derogatory] "'g**ks' in the jungle."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/OJWJE0x7T4Q' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

As usual, the band went nuts on the recording: jamming the groove for minutes longer than the final version, bashing on instruments, doubling the tape speed of the final section.

Marotta: We kind of played the song and then got into a jam, and that jam went on. It went on to a point where the song was over and we were just having fun. I do remember smashing a milk bottle and either me or Steve Lillywhite wandering around the room screaming and breaking things with a microphone in our hands.

Fast: I did a panel appearance at the Audio Engineering Society Convention with Wendy Carlos, and we were talking about recording. One of the things she'd come up with for [her 1968 album] Switched on Bach and some of the earlier albums was a technique called "hocketing," which took a complex line and exploded it into a lot of separate sonic sounds and played separately and re-combined for a much richer sound that kept the listener's interest. I thought, "If that worked for Mozart and Bach and worked for Haydn," I wonder if we can apply that to something Peter's got?" I broke out a few of the parts in a similar manner on a number of turnaround points. For a simple song, it has a lot of synthesizer overdubs that you wouldn't normally think would be done. It's very fussy and precise—it's more of the way I built electronic records than the way rock records get recorded. But it worked. And he liked it, which was the most gratifying part.

Lillywhite: By the time we finished the album, "Games Without Frontiers" was more like, [groans]. It was like, "We get it. OK, Peter. It's got a chant, and a cute lyric and Kate Bush," but the weirder ones for me resonate with me.

Fast: Everybody was falling all over [Kate Bush]. [Laughs.] I don't know if it was Steve or Hugh—of course, they were huge fans—but it was a huge race getting out to the control room to see who would get there first to adjust her microphones or fix her headphones. She came with at least one of her brothers, sort of her family bodyguards. She was just charming, just wonderful. She did exactly what everyone hoped we'd come up with.

Padgham: I think everybody fancied her really, particularly Peter. I ended up doing some stuff with her on [Bush's 1982 album] The Dreaming. Anyone involved in the sound of Peter's album she wanted as well. She was as much star-struck by him as he was with her. She was literally, musically speaking after that, trying to become the female version of Peter Gabriel, I think.

She was great. She's pretty crazy, as well. She just used to smoke spliff—joints—the whole time. She probably didn't on our sessions, but when I worked with her afterward, I was amazed that anything got done, particularly. She was so sweet, and she had this little tiny voice like this [imitates pixie voice].

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/3xZmlUV8muY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Though Lillywhite was nominally the producer and Padgham nominally the engineer, they took an all-hands-on-deck approach to record-making. But it was still a crucial album (and "Games Without Frontiers" a crucial song) for Lillywhite's personal confidence, proving that—even at the young age of 23 or 24—he could earn the respect of a full studio team.

Lillywhite: There was a real person moment on this involving Robert Fripp. Kate Bush is in the studio singing on "Games Without Frontiers," and Robert Fripp is in the control room because he'd come to do a guitar overdub on something. He's gone from producer to session guitarist, but if you know anything about Robert Fripp, he's very confident and full of himself. He's like the alpha male in the room. Kate's doing "Jeux sans frontières," but it doesn't sound great, so I'm coaching her to get the vocal how I want it to be. I hear this voice from the back of the control room, saying, "I'm sure she's got it right by now." I'm shaking inside. This is a real play by him because he's been the producer. I just completely ignored him, pressed the button and said, "Can you try that again please?" It was just a fleeting moment, and no one knows about this except for me. But as a producer, it was a pivotal moment in me keeping to my guns and getting what I wanted.

"I Don't Remember," the album's fourth single, pre-dated the recording sessions and was played on Gabriel's previous tour. It's the album's only appearance from Levin, who dominates the track with his monster Chapman Stick, a string instrument that allows players to simultaneously perform bass lines, chords and melodic lines. (On this track, Levin sticks to the low-end.) It's also one of two tracks featuring XTC guitarist Dave Gregory, who describes himself as a "Genesis fanboy" who was beyond intimidated by the bucket list studio experience.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/87yl5pbF-ZI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Dave Gregory, guitarist: The date was October 16, 1979. I remember that was date was printed on my memory. I was in awe of just being in the presence of this man I'd admired for a long, long time. He couldn't have been nicer—a decent man, no pretension about him at all. After we'd gotten over the initial embarrassment and handshakes and cups of tea and basic chit-chat, we got down to to work. He said, "Here's the song I'm having trouble with. I've had a couple guitar players in here, but they've not quite nailed the song I'm looking for." He said, "I'm wondering if we could work on an alternative tuning." The big guitar riff just goes "bang bang bang" and it's this downbeat with a long, ringing chord. I listened to it and thought, "Getting power out of that chord will probably require an open tuning."

We sat around the piano, and I said, "Can you show me the notes you played, and I can see if it's possible to tune the guitar to it?" Unfortunately, it was a six-note chord, and it meant that I had to retune the guitar to the most bizarre tuning alteration I've ever used. I'm winding away, thinking, "Oh, no. This [string] is going to pop at any time." This was a test for the guitar, but it coped OK. I didn't break any strings. When the part modulated halfway through the verse, it was just a simple matter of moving my thumb and two fingers up three frets. It still worked.

Pictured: Guitar tuning that Dave Gregory used on "I Don't Remember"

Photo courtesy of Dave Gregory

It was just a couple of hours. I was nervous as hell, as you can imagine. The studio assistants, one of whom who was a German lady named Marlis Dunklaus, was very helpful and reassuring. She could tell I was nervous. We had the amp set up in the stone room, which is where Phil Collins' famous first album was recorded. I was sitting there next to this amplifier, listening to the headphones as the track started. All that was on there was a guide vocal, Jerry Marotta's drums, Tony Levin's Stick, and some keyboard. That was it. It was very, very sparse, but it sounded amazing, just those basic elements. I thought, "I'm gonna f**k this up if I play over this. This is too good. What am I doing here?" [Laughs.] It took a few passes. It wasn't a first-take miracle by any means. I've listened to the song many times since then and thought, "I could have done that so much better if I hadn't been so nervous." There are a few wobbly moments that aren't quite in the pocket. I'd only been a professional musician for six months, and it was a bit intimidating.

Gregory also played a simple part on "Family Snapshot," one of the album's most progressive, elaborately arranged tunes, featuring a scene-stealing solo from saxophonist Dick Morrissey.

Fast: The whole back half of the song was part of an instrumental that grew out of soundcheck jams on the second album's tour. But it wasn't really a song. It didn't firm up until the tour and the third album's writing.

Marotta: It's got that epic [quality]. We were playing it, and the sections were kind of there, but we didn't know where to put them. As we played them, I had the idea, "Let's start here, go here." We played that, and Peter liked it. That solidified it.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/Uh9wIVZBhT0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Gregory: He said, "I'll play you the part on piano." I just want some electric rhythm guitar in the second verse. I had my notes there and wrote the changes down. They ran the track, and I played along, but I thought, "Oh, my god. Something's wrong. What's happened?" I said, "Sorry, guys, this sound's like it's in a different key." They all remembered, because they hadn't revised the track for a number of weeks, that they'd changed the key so it suited his voice better.

We did start work on a third song, "Bully for You." He said, "I haven't done much of this yet, but see what you can do with it." I was kind of tired—it was late afternoon. I was sort of playing along to what they had on tape and wasn't getting very far. It required a bit more thought because it wasn't straight-ahead chords. Then the phone rang, and it was XTC's manager, who said, "David, don't go back to Swindon tonight. We're been booked for "Top Of The Pops" tomorrow. We'll meet you at the hotel [in London] and go to the BBC tomorrow." My fate was decided. They were talking about coming back in the morning to work on this song. I had to say, "Sorry, guys. We're promoting 'Making Plans for Nigel,' and I've got to do the most important pop show on British television." I couldn't believe I was turning down a studio opportunity with Peter Gabriel to do the television show "Top Of The Pops." I must have arrived! This time last year I was driving a van around Bristol delivering mail, and now this!

Pictured: [From left to right] Hugh Padgham, Steve Lillywhite, Peter Gabriel and Atlantic A&R John David Kalodner at Townhouse Studios in Shepherd’s Bush, London

Photo courtesy of Larry Fast

The team recruited Paul Weller, guitarist of mod/punk band the Jam, to record a guitar track for "And Through the Wire," one of the album's most straightforward, rock-flavored moments.

Padgham: He was a sort of angry young man. I remember it was very funny when we asked him to come do a session. In the Townhouse, there were two studios, and the Jam was in studio one when we were in studio two. He came down to the session, but he didn't have a guitar. He'd never done a session, but he didn't think he had to bring a guitar! He turned up, and there were no guitars around.

Lillywhite: With "And Through the Wire," one of the problems is that the guitar was overdubbed and wasn't played with the band. It has this sort of overdubbed thing to it—it's not in the DNA of the recording. A lot of the electric guitar that David Rhodes did is fantastic—the "Intruder" acoustic against those drums, the long-note sustained stuff in "Biko" and "Games Without Frontiers." But the worst thing about [the album] is the rock guitar. I'm sorry to say. "And Through the Wire" and "Not One of Us" don't have that classic, mysterious thing. Rock music probably needs cymbals. Maybe that's why there's something a little disconcerting about them.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/qDHpbZ_0n6E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Penultimate track "Lead a Normal Life" is the farthest vibe imaginable from "rock." Over a chiming piano line and stark marimba riff, Gabriel channels the isolation one might experience in a mental hospital.

Fast: "Lead a Normal Life" was built by subtracting things until there was virtually nothing left but the essence of the song: a single piano line and a little wispiness. If you heard the original rhythm track, you'd recognize it was the same song melodically, but it's hard to believe the transformation.

There was a big band recording. I don't remember if everybody was live on it, but it was a huge Phil Collins drum [piece], with Morris Pert on percussion, a full bassline. Linearly, it's all there. I have reference mixes over the four or five months that this album was going, and each one becomes more sparse. It's the exact opposite of what most bands do, and that's one of those creative Peter things that was facilitated by the team around him—by Hugh and Steve and me throwing in my ideas. Peter kind of led the transition: "What would it sound like if we took this out?" Until there was almost nothing left.

Lillywhite: "Lead a Normal Life": Oh, my god! Incredible. The second U2 album had the song "October" on it, and it has a similar sort of feel. It really gets you, that stark thing. When I listen to this, it's like I'm in a mental hospital. That's what you want from a record, isn't it? To paint a picture that's just mind-blowing.

Marotta: That was fun to play live because the idea was to annoy the audience by playing that little riff [hums melody] over and over again to make people uncomfortable.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/-GgEu0Sbiv8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

And the album ends with the anthemic "Biko," a sort of eulogy for the South African anti-apartheid activist Steven Biko, who died in police custody in 1977. The arrangement is thrillingly minimal, each note and beat vibrating with emotion — from the chanted choruses to Fast's climactic solo on "synthesized bagpipes."

Lillywhite: I don't know whether the bagpipes are such an ethnic sound for Africa. It is [a strange combination], but maybe we couldn't think of a better sound to do those sort of pads.

Fast: We had to reverse-engineer the story on that. As it turned out, the drone was a through-piece along with the drums, and there was the big surdo drums and electronic pattern on the PAiA that formed the core of the song. But it had these breaks where there was nothing there. I was playing around with melodic structures over a drone. In the patches, I was working with these narrow-width pulse waves, and it started sounding like a bagpipe if I detuned it enough with harmonizers and things. We said, "That sounds pretty good," and then we tried to figure out how it tied in to this story about Stephen Biko and South Africa. After a little bit of research, it turned out that during the Boer War in South Africa between the British Colonial, Dutch and German forces, one of the Scottish military units was very instrumental. So we went, "OK, there's our hook!" So we had a historical legitimacy to using a bagpipe sound other than "That works musically."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/luVpsM3YAgw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Gabriel isn't always an "easy" collaborator. His slow, often tedious process of analysis and reflection doesn't appeal to everyone. But for the main contributors on his third LP, it's part of the magic that makes him tick.

Marotta: We were very close-knit, kind of a family dynamic. We were around each other a lot, and it could get frustrating. Everybody loved Peter and would do anything for Peter. Everybody at some point wanted to kill Peter. He'd have these ideas he'd want to do, and the last thing you'd want to say to is "You can't do that" because that's exactly the thing he'll want to do. But in a nice way, not in a nasty way. I remember we played a big festival in France, like 180,000 people. And they said, "Whatever you do, don't throw yourself into the audience because from the moment you're in the audience and they're passing you around, we may never see you again. Just don't do that." And, of course, he threw himself into the audience.

Fast: He's one of the few artists where I learned things from him. There are a lot of talented people I've worked with over the years. They'd usually bring me in to layer a little extra something into what they're already doing. But with Peter, it was challenging—learning how to approach things differently, think of things in an unconventional way. He's really good at that, and that's why he's the talent that he is.

Lillywhite: It was a coming-of-age for me as a producer.

Padgham: It was a magical time. It freaks me out that it was 40 years ago.

Gregory: After we'd finished for the afternoon [after his session], we all went to the canteen and had dinner. We had a nice chat around the dinner table, and the subject of touring internationally came up—passports and all that. Someone said, "What occupation have you got on your passport?" Peter said, "I think mine says 'musician,' but when I renew it, I'm going to change that to 'humanist.'" I thought, "That's very interesting because that's exactly who he is." He's such a decent man. They say, "Don't meet your heroes," and that's good advice. But with Peter Gabriel, you make an exception.