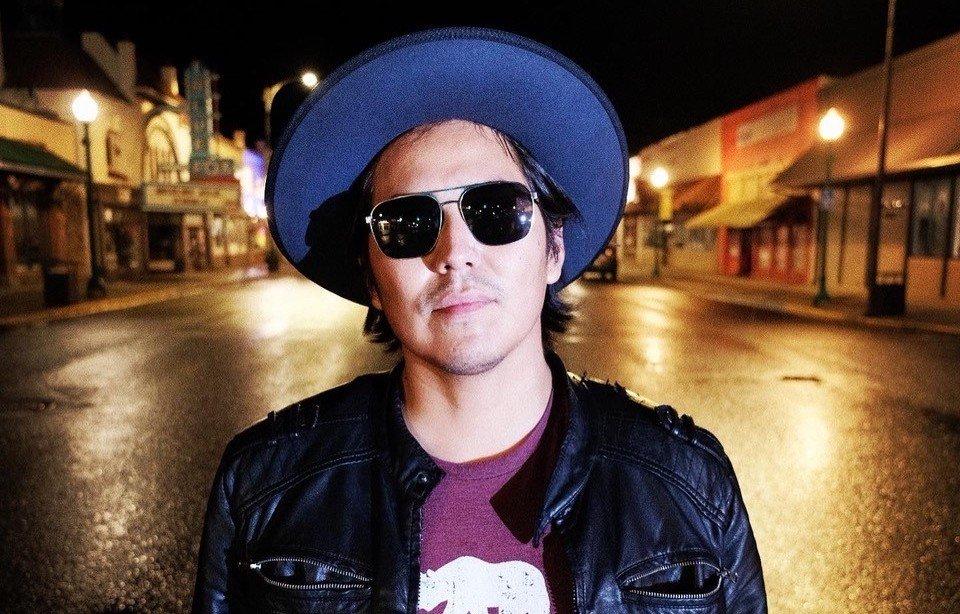

Photo: Jacob Shije

interview

Meet Levi Platero, A Formidable Guitarist Bringing Blues-Rock To The Navajo Nation

"I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar," the guitar scorcher tells GRAMMY.com. But limelight or not, Levi Platero's illuminating a path forward for blues-rock in Indigenous communities.

Back in 2022, Levi Platero spoke to GRAMMY.com about his then-new album, Dying Breed. Two days later, a city bus slammed into his touring van.

The Arizonan blues-rock guitarist, who hails from the Eastern Agency of the Navajo Nation, was on a West Coast tour. After lunch in downtown Portland, kaboom: their van was totaled. When hearing about this close call, something poignant Platero had said came to mind.

"I just want to be able to keep going, man. Especially with blues music, you can kind of play forever," he expressed near the end of the interview. "Not to put down any other musical genres, but I can't see myself being a rap artist at, like, 60 or 70 years old. I can see myself being a blues-rock guy until the day I die."

Looking decades into the future, it's hard not to imagine Platero and his music being buoyed by the community he helped create.

An absolute burner on his instrument — behold Dying Breed highlights like "Fire Water Whiskey" and "Red Wild Woman" as examples — he stands with few others as a blues-rock great in the Navajo Nation. Or just one, in his estimation: Mato Nanji of the band Indigenous, who he affectionately calls "Big Brother."

Perhaps Platero — who's eyeing a new van, and getting ready to head back into the studio in late spring — will also inspire others in his wake. And the more he sings and plays, the more likely that outcome seems — that his "dying breed" will flourish forever.

Read on for an in-depth interview with Platero about his latest album, how Indigenousness inspires his artistry, and why he "doesn't want to be a superstar — I just love to play."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Tell me about your background, and the musical community that brought you up.

I grew up in church. My dad was an evangelist. He went out, did things for the church and that kind of community. I would sometimes tag along, but I was getting involved with some of the worship leading and stuff like that. But my dad would write his own tunes, and he would make his own music later on. And I would go out and help him just play drums. I was just in the background area.

Later on, I started playing guitar, and listening to a lot of old gospel tunes and gospel hymns. That's where I got introduced to the blues. And after I learned about the blues, from then on, that's all I ever really listened to.

Now, a lot of things have changed. I'm out in the world doing my own thing and writing my own music about some things that I feel — not necessarily anything that has to do with the church community. But, that's where I got started.

What's your conception of the blues? To me, it's kind of like the word punk. It can be a certain way of playing power chords, or an entire state of being — an opposition to the status quo. Likewise, the blues can mean 12 bars, or the totality of human angst.

I think it's probably the rawest form of musical emotion that I can feel — that I've ever really felt for myself. But that's only my own opinion. That's my perception of it. I always hear a lot of people say that it's a little redundant, and it's kind of boring and whatnot. But for me, it's something that's just really raw, emotional, really straightforward.

And as far as the lifestyle, I mean, I would have to say that being a part of a blues community, I'm really [grounded among] people who are really respectful.

And the people who are respected the most are the people who generally [may] not have the most talent, but collectively, they're a great person — they have a great personality. They really enjoy one another's music, and they're really involved in the blues community where they help each other out, or they get each other's gigs, they sit in.

It's just this really friendly dynamic in that area. Rather enjoyable. I love it.

Living or dead, whether you know them or not, who are the guitarists that formed you?

I have to say my biggest influence was Mato Nanji from Indigenous. They were a Native American blues-rock group back in the day, probably in the early 2000s. They made a really good name for themselves in the blues circuit, and I [had] the opportunity to actually travel and open up for him and also join his band.

I really learned a lot from kind of hanging out with him and just being a part of his group. He's one of my biggest guitar influences and as a person — as a role model.

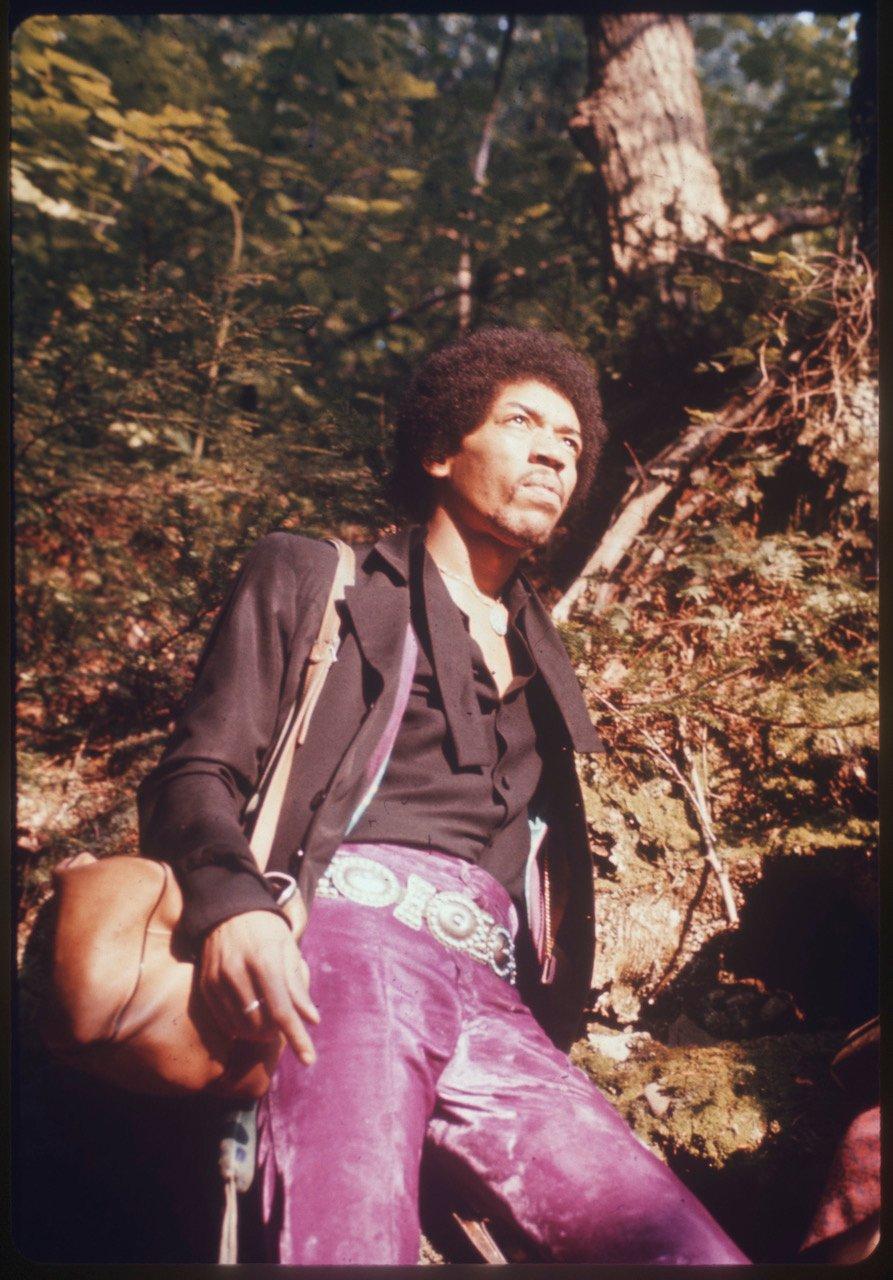

Otherwise — people who I have not met — I have to say, of course, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan. David Gilmour was a good influence. Doyle Bramhall II — little Doyle, big Doyle.

And then as far as in my community, back in Albuquerque, Darin Goldston — he plays for the Memphis P-Tails. He hosts the blues jam every Wednesday night. Whoever is upcoming and just wants to play some blues, they come out and jam. It's pretty awesome.

And, of course, Ryan McGarvey. If you don't know who that is, he's in the blues-rock circuit. He's a great guy — a pretty influential person.

With all those inspirations on the table, how did you start to develop your own voice on the guitar?

Just being well-seasoned, I guess. Just constantly playing over time. For some people, it doesn't happen right away, to find their own sound. With other people, they have to go through seasons and learn new things, until one day, they really become identifiable just by the first couple of notes they play.

I don't think it was a hard thing for me. I was just playing until it started becoming identifiable to some people's ears.

I'm sure specifically Indigenous influences must make it into your sound in some way.

Yeah, of course. I mean, those drum patterns, those drum beats — they're really similar to all that chain gang stuff they used to do back in the day. Those call-and-repeats and stuff like that.

Sometimes I try to incorporate that into some of the music I have. Indigenous influences are there, as far as jewelry and hats. Even as far as a little bit of graphic design. That stuff definitely makes its way into the fashion part, and the promotion.

Tell me what you were trying to artistically impart with Dying Breed.

I just wanted to put out an album, because I need to. I love writing my own music, and of course, the ultimate goal is to make music that inspires and reaches people — and also inspires Indigenous artists and people at reservations to go after whatever they want to go after.

Because it's like: yeah, there's education on the rez, but as far as outlets — fashion, music, art, film — some of those things don't make it as far as the reservation.

So, just being an Indigenous artist in itself — to be able to write and put out music like that, for others to hear — I guess that's kind of the ultimate accomplishment in what I'm trying to do. Just to keep inspiring people — inspiring my own people, natives all across the U.S.

**Can you talk about your collaborators on Dying Breed?**

That's actually kind of funny, because I'm doing most of the work on the album.

I did all the guitars. I did all the bass guitars. I did the lead vocals. My cousin [Royce Platero] did the drums. I only had my rhythm player [Jacob Shije] play on, like, two tracks, and he was only doing small-fill guitars and that's it. I had a good friend of mine named Tony Orant come in and play keys on two of the songs as well.

As far as all the songs go, I wrote all of them. I composed everything. I came up with the arrangements and the core progressions. I mean, it's all mine.

One of my favorite people and producers right now, a sound engineer who helped me with the album: his name is Ken Riley and he's based out of Albuquerque. He has a really beautiful and awesome old adobe recording studio, right by the Rio Grande. It's called Rio Grande Studios. He's kind of a legend. He's worked with so many artists and still works with big-name, major artists.

I think he recently just worked on Micki Free's album. He worked on a couple of songs with Santana and Gary Clark Jr. Christone ["Kingfish"] Ingram. He works with some heavy hitters, and I approached him. I was introduced to him by a friend of mine named Felix Peralta. He told me to meet this guy and said, "You need to do your next record here."

So, we finally got to meet, me and Ken, and it just kind of went from there and everything came out really good. I really enjoy this record. It's probably my favorite one that I've done so far.

*Levi Platero. Photo: Jacob Shije*

Are there any other Indigenous musicians in the blues and/or Americana world that you want to shout out in this interview?

Foremost, as far as blues guitarists: I have to give a shout-out to my — I call him Big Brother. Mato Nanji, and that means "standing bear." He's a big role model, and probably the only other Indigenous blues-rock guitarist out there besides me who is trying to do it.

Anything else you want to mention before we get out of here?

No, I just want to keep playing. I just want to keep doing this — meet more people, keep expanding. I don't want to be in some crazy-a— limelight. I don't want to be a superstar. I just love to play. I just want people to enjoy my music and come vibe at the shows. That's it.

Photo: Rick Kern/WireImage

list

10 Must-See Acts At BottleRock 2023: Cimafunk, Christone "Kingfish" Ingram, Danielle Ponder & More

Ahead of the 2023 BottleRock festival in California’s Napa Valley, held May 26-28, preview some of the notable up-and-coming acts who will hit the festival’s four stages.

Roughly 120,000 people will head to California's wine country May 26-28 for the 10th BottleRock festival, which serves up music, food and libations at the Napa Valley Expo. BottleRock leans in on the food and beverage experience: on social media they refer to themselves as "a food festival with music playing in the background."

On the festival’s culinary stage, headline musical acts join celebrity chefs and personalities for cooking demonstrations: at past festivals, Martha Stewart has chopped vegetables alongside Seattle rapper Macklemore, and Snoop Dogg has rolled sushi with Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto. More than a dozen wineries participate, as well as breweries and distilleries. The festival also features a silent disco, spa, pop-up live music jam sessions and art installations.

But beverages, food, art, and massages are not the headline act: Spread across four music stages, more than 20 musical artists perform each day. Post Malone and Smashing Pumpkins headline on Friday, Lizzo and Duran Duran on Saturday, and Red Hot Chili Peppers and Lil Nas X headline Sunday. Well-known marquee acts will play early-evening sets: Billy Strings and Bastille on Friday, Leon Bridges and Japanese Breakfast on Saturday, Wu-Tang Clan and the National on Sunday.

A handful of festival acts will also feature at BottleRock Presents "after show" performances at venues in Napa, San Francisco and around the Bay Area May 23-28. Some of these after-show performances are sold out, but tickets are still available for Cautious Clay, Lucius, the Wrecks and several other acts. At the time of writing, three-day festival tickets are sold out but individual day tickets are still available.

In addition to the many big-name acts on the bill, noteworthy artists further down the roster will be performing from about noon onward. Representing pop, punk, blues, hip-hop, indie rock and more, the following 10 rising artists stand out for their originality, style, and approach.

Oke Junior

Oakland, California-born, Napa-raised Matthew Osivwemu raps under the name Oke Junior. He made music throughout middle school and high school: his song "Elmhurst" is a reference to Elmhurst Middle School in Oakland.

An older brother mentored Osivwemu , encouraging his early musical pursuits and making sure he was a student of the rap game. "The first time I rapped for him, I thought I was raw. He broke it down straight up and said ‘Man, that ain’t it. If you’re gonna rap, you gotta make sure it has meaning…don’t be out here just saying anything," Osivwemu said during a "Sway in the Morning" interview last year.

In 2017, Oakland hyphy rapper Mistah F.A.B. spotted Osivwemu at open mic nights in Sacramento, and took the young rapper under his wing. In 2016, Oke Junior tweeted that he wished he could have performed at BottleRock, and then joined Too Short onstage in 2019. He’ll perform at 1 p.m. on the Truly Stage on Sunday.

Cimafunk

Erik Alejandro Iglesias Rodríguez, a.k.a. Cimafunk, is a Cuban singer who performs funky Afro-Cuban music with a nine-piece band with an energetic intensity that has drawn comparisons to James Brown.

For his 2021 album El Alimento he collaborated with Lupe Fiasco, CeeLo Green, and funk legend George Clinton, an experience he said was like "talking to a friend." The album was nominated for a GRAMMY Award for Best Latin Rock or Alternative Album at the 2023 GRAMMY Awards.

Rodríguez grew up in a tight-knit community in Western Cuba, surrounded by music: Mexican music, Christian music, and salsa, mixed with African rhythms. "We had a big family. We were always dancing in the house and every Sunday, we were dancing– salsa and other types," Rodríguez told GRAMMY.com. "Everybody loved music and we all listened to music the whole day. In any house, at some point, many types of music would be playing — Mexican music, reggaetón, Lionel Richie, or Michael Jackson, that was my fave."

Cimafunk performs at 4:15 p.m. Sunday on the Allianz stage.

Danielle Ponder

Ponder, a former public defender from Rochester, New York, is also a powerful R&B/soul singer who has performed on late-night talk shows and at festivals like Bonnaroo and Lollapalooza. Ponder was serious about her legal work, but was also making music on the side for several years She made the jump full-time to music after she turned 40.

Released in 2022, Ponder's debut album Some of Us are Brave is filled with upbeat, spiritual bangers and chilled-out confessionals. The music often pulls way back, allowing Ponder the quiet space to convey to listeners that she feels their pain and their joy, and she wants to uplift them. The album's title track is a timely anthem for social justice: "all we want is to be ourselves … we don’t want problems," she sings.

"We did an album and everything through law school. I just always felt like I didn't want to be struggling. I had this fear of financial instability, and so I just was like, I can't do music full time. But eventually it just pulled me," she told NPR.

Ponder performs at 1:45 p.m. Saturday on the Jam Cellars stage.

Joey Valance & Brae

This Pennsylvania hip-hop duo, with their cocky, high energy Beastie Boys vibes and pop culture references to topics like Star Wars and fresh produce bring a heavy dose of prankster, '90s hip-hop style — but from a humorous, adolescent Gen Z perspective. Scroll to the bottom of their Spotify page and you’ll see this: "Who tf reads Spotify bios."

The rapper-producers — real names Joey Bertolino and Braedan Lugue — are longtime fans of early rap innovators like Biz Markie, Eric B. & Rakim and the Beastie Boys, but also EDM. They met at Penn State University and both credit their fathers with being big musical inspirations. The duo make most of their music in Valance’s bedroom. "He comes over and we just mess around until something fun comes out of it what we f—ing love," Valence told Ones To Watch.

After gaining traction on TikTok, the duo performed their song "Double Jump" on the "Ellen DeGeneres Show" and won a $10,000 talent show grand prize. They now have more than 850,000 followers on TikTok.

Joey Valance & Brae perform at 7:15 p.m. Sunday on the Truly Stage.

Maude Latour

The Sweden-born singer has an enviable breakout story In March 2020, during the early pandemic lockdown, Latour — who was a student at Columbia University — posted a video of herself singing "One More Weekend," an upbeat tune about college heartbreak, to TikTok, where it has since been viewed more than 455,000 times. A year later, Latour was applying to summer jobs when record labels approached her and she signed with Warner Records. Last summer, she performed at Lollapalooza on the same day as Metallica.

A child of journalists, Latour studied philosophy in college, and her songs explore a range of emotions tied to relationships, death, messy bedrooms, and existentialism.

"I feel connected to this overpowering awareness of my mortality. It is what makes life beautiful. This is my ‘thank you’ to existence," she told Billboard.

Maude Latour performs at 2:45 p.m. Saturday on the Allianz Stage.

Thunderstorm Artis

Growing up in Oahu, Thunderstorm Kahekhili Artis played in a family band with his dad, Ron Artis, an artist and Motown session musician who, played with artists such as Michael Jackson, Van Halen and Stevie Wonder.

After touring with his older brother Ron Artis II, Thunderstorm was invited to perform at the wedding of Crazy Rich Asians director Jon M. Chu, and was a finalist in the 2020 Spring season of "The Voice," where he performed renditions of "Blackbird" by the Beatles and songs from artists like Louis Armstrong.

Thunderstorm has gone on to perform his blendings of folk, rock, soul and country music alongside artists like Jack Johnson and Booker T. He’s been known to play renditions of songs from artists such as David Bowie, Leonard Cohen and Elton John.

Thunderstorm Artis performs at 12:15 p.m. Sunday on the Verizon stage.

Ayleen Valentine

The 21-year-old from Miami dropped out of Berklee College of Music in 2021 to pursue music full time. She combines guitar, piano, and saxophone with electronic beats to make moody dream pop.

Valentine has said that she loves to watch videos of her favorite artists before she takes the stage, listing a who's who of famous rock stars that inspire her: "Thom Yorke of Radiohead. Mitski. I used to love Kanye — not so much anymore. James Blake. Axl Rose is very theatrical. Fiona Apple is cool and very scary."

Valentine released Tonight I Don't Exist, a seven-song EP of bedroom pop, last year, and more recently released a video for the song "Next Life" from that EP.

Ayleen Valentine performs at 12:30 p.m. Friday on the Jam Cellars Stage.

Meute

The head-bobbing, dancing crowd and flashy, bright lights of a Meute show look almost exactly like any average club scene, but instead of a DJ and turntables and laptops, crowds see 11 people wearing marching band uniforms and holding brass instruments.

Like most brass bands, the 11-piece German brass collective Meute offers up lush harmonies and expressive horn solos backed by marching band percussion. But Meute is a "techno marching band," that aims to create a high-energy, hypnotic club vibe with marching band instruments. Meute founder and trumpet player Thomas Burhorn loved the ecstasy and intensity of going to raves, but thought it would be more interesting and exciting if there was a live band onstage instead of a DJ.

"We do interpretations…It’s a nice part of art, and a nice part of the history of music… when you can give the composition something new, when you can see it from another point of view, it’s a beautiful thing," Meute founder and trumpet player Thomas Burhorn told Variety.

The group toured 18 cities across North America last summer and performed at Goldenvoice’s Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.

Meute performs at 8:45 p.m. Saturday on the Allianz stage.

The Alive

The members of The Alive are teenagers from Southern California, but they make music that sounds like a collage of '90s and early 2000s alternative rock.

"We’d grow up going surfing and skating. In the car, our parents would start playing music," singer and guitarist Bastian Evans told an interviewer. "I didn’t pay attention the first four or five years I was alive – but after a while, I started really listening to what was playing, and got a connection to some of the bands, especially Queens of the Stone Age. My dad would play it all the time in the morning, especially on the way to school."

The Alive have performed at Lollapalooza Chile and Ohana Fest, and opened up the main stage at BottleRock in 2021 and played an after-party show with fellow Laguna Beach musician Taylor Hawkins and his former side band Chevy Metal.

The Alive was named one of Stab Magazine’s "30 Under 30 Culture Shifters of Tomorrow" and has performed benefit concerts for the Surfrider Foundation, Surfers Against Sewage in England, Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii, and Save The Waves.

The Alive perform at 12:30 p.m. Sunday on the Jam Cellars Stage.

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

When 24-year-old Christone "Kingfish" Ingram won the Best Contemporary Blues Album award at the 2022 GRAMMYs, he told the crowd, "For years I had to sit and watch the myth that young Black kids are not into the blues, and I just hope I can show the world something different."

His debut album, Kingfish, produced by Tom Hambridge, was released on Alligator Records in 2019, and earned him a nomination for Best Traditional Blues Album at the 62nd annual GRAMMY Awards.

Ingram grew up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, playing drums, bass, and guitar. He studied music at the Delta Blues Museum under Bill "Howl-N- Mad" Perry and Richard "Daddy Rich" Crisman, and was playing gigs around town by seventh grade.

In 2014, he performed for Michelle Obama at the White House with the Delta Blues Museum band. Ingram joins a long legacy of artists to emerge from Clarksdale: John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, Sam Cooke, Muddy Waters are just a few.

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram performs at 5:45 p.m, Sunday on the Allianz Stage.

Get To Know 5 Asian Artists Taking Center Stage At 2023 Festivals

Dave Mason

Photo: Chris Jensen

news

Dave Mason On Recording With Rock Royalty & Why He Reimagined His Debut Solo Album, 'Alone Together'

The ex-Traffic guitarist has played with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to George Harrison to Fleetwood Mac—now, he's taken another stab at his classic 1970 debut solo album

Dave Mason is charmingly blasé when looking back at his life and career, which any guitarist would rightfully give their fretting hand to have. "I did 'All Along The Watchtower' with Hendrix," he flatly tells GRAMMY.com, as if announcing that he checked the mail today. "George [Harrison] played me Sgt. Pepper's at his house before it came out," he adds with a level of awe applicable to an evening at the neighbors' for casserole.

Last year, Mason re-recorded his 1970 debut solo album, Alone Together, which most artists would consider a career-capping milestone. When describing the project's origins, he remains nonchalant: "It was for my own amusement, to be honest with you."

Fifteen years ago, when the Rock And Roll Hall Of Famer started to kick around the album's songs once again in the studio, he didn't think it was for public consumption—until his wife and colleagues encouraged him to reverse that stance. On his latest release, Mason gives longtime listeners and new fans an updated take on the timeless Alone Together, this time featuring his modern-day road dogs, a fresh coat of production paint and a winking addendum in the title: Again.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//Xd56ap_aa4k' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Alone Together…Again, which was released last November physically via Barham Productions and digitally via Shelter Records, does what In The Blue Light (2018) and Tea For The Tillerman² (2020) did for Paul Simon and Yusuf / Cat Stevens, respectively. It allows Mason, a prestige artist, to take another stab at songs from his young manhood. Now, songs like "Only You Know And I Know," "Shouldn't Have Took More Than You Gave" and "Just A Song," which demonstrated Mason's ahead-of-the-curve writing ability so early in his career, get rawer, edgier redos here.

Mason cofounded Traffic in 1967 and appeared on the Birmingham rock band's first two albums, Mr. Fantasy (1967) and Traffic (1968). The latter featured one of Mason's signature songs: "Feelin' Alright?" which Joe Cocker, Three Dog Night and The Jackson 5 recorded. After weaving in and out of Traffic's ranks multiple times, Mason took the tunes he planned for their next album and tracked them with a murderers' row of studio greats in 1970. (That year, Traffic released John Barleycorn Must Die, sans Mason, which is widely regarded as their progressive folk masterpiece.)

Over the ensuing half-century, Mason has toured steadily while accruing an impressive body of work as a solo artist; Alone Together...Again is a welcomed reminder of where it all began.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Dave Mason to talk about his departure from Traffic, his memories of the original Alone Together and why the new 2020 takes are, in his words, "so much better."

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/bOV7dsNsnd4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Where do you feel Alone Together stands in your body of work? Is it your favorite album you've made?

No, I wouldn't say it's the favorite, but it's sort of spread out. When people ask me, "Well, what's your favorite music? What are you listening to?" I'm like, "I don't know. Which genre do you want me to talk about?" I can't pick it out and say it's my all-time favorite. There are other things I like just as much.

I mean from your solo canon, specifically.

Well, even from a solo thing, 26 Letters, 12 Notes, which I put out [in 2008], went right under the radar, because trying to put new stuff out these days is … an exercise in futility. And that was a great album! Really good. [Alone Together] definitely had great songs on it, and it still holds up, redone. So, from that point of view, it's great. It's probably one of my faves, yes.

When you made the original album, you had just left Traffic, correct?

Pretty much after the second album [1968's Traffic], I moved over here in 1969, to the U.S., for a couple of reasons. Traffic was not a viable option for me anymore, from the other three's point of view. So I decided to come to the place where everything originated from, which is America. Bluegrass, which had its roots in Europe and everything else, is uniquely American music. So that, and probably the 98-cents-to-the-dollar taxes, too. But I mostly came here for musical reasons.

Which divergent creative directions did you and the other Traffic guys wish to go in?

Had that not have happened, all those songs on Alone Together would have been on the next Traffic album.

Read: WATCH: Dave Mason & The Quarantines Uplift With New Video Version Of "Feelin' Alright"

You had quite an ensemble for the original Alone Together: pianist Leon Russell, vocalist Rita Coolidge, bassist Chris Etheridge and others. Were there specific creative reasons for involving these musicians? Or was it more in the spirit of getting some friends together?

I knew Rita and a few other people from early on, being in Delaney & Bonnie. All those people kind of knew each other. Leon Russell was new. I think Rita was going out with Leon at the time. A lot of them were gathered together by Tommy LiPuma, who coproduced Alone Together with me. Otherwise, I was just new here. I didn't know who was who.

Many of those guys were the top session guys in town: [drummers] Jim Keltner, Jim Gordon and [keyboardist] Larry Knechtel, for instance. Leon, I had him play on a couple of songs because I'd met him, I knew him, and I wanted his piano style to be on a couple of things. He put the piano on after the tracks were cut.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/k5fn0dbSw18' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Let's flash-forward to Alone Together… Again. Tell me about the musicians you wrangled for this one.

Well, that's my band, the road band that I tour with. [Drummer] Alvino Bennett, [guitarist and background vocalist] Johnne Sambataro—Johnne's been with me for nearly 40 years, on and off—and [keyboardist and bassist] Tony Patler.

Other than the slight differences in arrangements, there's more energy in the tracks. Other than the vocals, they were pretty much all cut live in the studio. The solos were cut live, because that's my live road band. "Only You Know And I Know," "Look At You Look At Me," "Shouldn't Have Took More Than You Gave," all those songs have been in my set for 50 years, on and off, so they knew them.

If I never had that session band on the original album and could have taken them on the road for a month, then that original album would have had a little more of an edge to it, probably. This new incarnation of it has more of that live feel. Those boys knew the songs. They didn't really have to think about them, but just get in there and play.

Aside from that, there are slightly different arrangements. "World In Changes" is a major departure, "Sad And Deep As You" was basically a live track cut on XM Radio probably 12, 14 years ago and "Can't Stop Worrying, Can't Stop Loving" is a little bit more fleshed out, which I like. The other songs pretty much stick to the originals.

"Just A Song," I think, has a little more zip to it. It's got the addition of John McFee from The Doobie Brothers, who put that banjo on it, which is cool. Then there's Gretchen Rhodes, who does a lot of the girl background vocals on these tracks.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/7G1p7MBreu8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

What compelled you to change up the rhythm of "World In Changes"?

I just wanted to see what would happen, taking one of my songs and adapting it to something else. I have a version of it cut the way it was originally done, and it was a question of whether I stick to that and put that on the album or do something exciting and totally different. To me, it came out so cool. The sentiment is timeless, and I wanted something on there that was new—an older song, done in a new way.

It seems like you still feel poignancy and urgency in these songs. Besides the fact that the album's 50th anniversary just passed, why did you return to the well of Alone Together?

Well, I started playing around with doing this 15 years ago. Mostly, it was for my own amusement, to be honest with you. But then, as it started to come together, and it was approaching 50 years since the [release of the] original, my wife and some people around me were like, "You should put this out." That's how it all led up to this.

Any other lyrical or musical changes that the average listener may not notice?

As to whether this ever reaches the ears of some new people, it would be nice. It seems unless you have some Twitter trick or social media thing happen, trying to get people aware [is difficult]. In other words, if a younger audience could hear this, I'm pretty sure they would like it. You'll probably have some people out there—the purists—but otherwise, I don't know.

"Sad And Deep As You" is so much better than the original version, frankly. To me, it holds up. I think my vocals are better, which is one of the big reasons why I decided to redo it in the first place.

When you said "purists," there was an edge in your voice.

[Long chuckle.] Everybody's got their tastes and opinions, and that's the way that is. Same reason they booed Bob Dylan when he had The Band behind him. Some people are that way.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//CHh_ox0HtyA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Even if people aren't familiar with the original album, I'd think your backstory would resonate with them. Your role in George Harrison's All Things Must Pass comes to mind.

Yeah, I played on a bunch of things. With All Things Must Pass, I pretty much just played acoustic guitar stuff in there with a group of people … George gave me my first sitar and played me Sgt. Pepper's at his house before it came out. I did "All Along The Watchtower" with Hendrix.

A lot of it's available on my website. There's a lot of cool stuff on there. On my YouTube channel, there's a great live version of "Watchtower" from the Journey and Doobie Brothers tour we did four years ago. But we'd be here for another half hour or more if we went over everybody I appeared with and everything I've been on.

Read: It's Not Always Going To Be This Grey: George Harrison's 'All Things Must Pass' At 50

Regarding Hendrix, that's an experience that not many other people can say they've had.

Very few. Very few. There are a lot of great guitar players out there, but there are no more Jimi Hendrixes.

You also played with Fleetwood Mac in the '90s, yeah?

I was with Fleetwood Mac from '94 to '96. We did an album called Time, which sort of went under the radar somehow. It didn't get promoted.

Why was that?

I don't know. It's not a bad album, but Warner Bros. was trying to force the issue of getting Stevie Nicks and whatshisname back in there.

Yeah, Lindsey. Christine McVie was on the album, but she didn't go on the road with us. It was kind of weird. The only original members were Mick [Fleetwood] and John [McVie]. It was a little bit like a Fleetwood Mac cover band, but it was cool. It was fun to do for a couple of years, but then they got back together again. C'est la vie. There you go.

Anything else you want to express about reimagining Alone Together 50 years down the road?

I don't think it's just the fact that it's my stuff because there are certain songs I've done that I would not address again. But the thing about those songs is that they all have very timeless themes. "World In Changes," I mean, that could have been written a month ago. To redo them doesn't seem that out of place to me.

Jimi Hendrix

Photo: Daniel Teheney/Authentic Hendrix LLC

news

Director John McDermott Talks New Jimi Hendrix Documentary, 'Music, Money, Madness … Jimi Hendrix in Maui'

Ahead of an exclusive premiere of the film this week, presented as part of the GRAMMY Museum's COLLECTION:live programming, GRAMMY.com caught up with McDermott to discuss how the documentary continues Hendrix's lasting legacy

Jimi Hendrix accomplished more in five years than most artists achieve in a lifetime. Songs like "Hey Joe," "Purple Haze" and "Voodoo Child" are classic rock staples. His innovation on the electric guitar influenced generations. He's responsible for seminal moments now emblazoned in the annals of rock: the time he set his axe ablaze at the Monterey Pop Festival or the time he played an instrumental version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" on a Sunday morning coming down at Woodstock. In the late 1960s, Hendrix was also the pensive leader of America's counterculture movement.

The Seattle-born musician left us far too soon. On Sept. 18, 1970, the 27-year-old died at the bohemian Samarkand Hotel in Notting Hill, England. The cause: asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates. Fortunately for fans, old and new, Hendrix left a cache of unreleased music. Now, thanks to archivist John McDermott and the Experience Hendrix family-run company, his lost music allows us to discover another untold chapter in the life of this mercurial musician.

The new narrative: the backstory on the making of Rainbow Bridge, a bizarre and controversial independent movie released in 1971. Directed by Warhol acolyte Chuck Wein, the project was financed by a $500,000 advance from Reprise Records, with the promise of a Hendrix soundtrack.

In his new documentary, Music, Money, Madness … Jimi Hendrix in Maui, McDermott attempts to set the record straight about this boondoggle. The feature-length film, which drops Nov. 20, includes never-before-released original footage and new interviews with those who were there. (Live In Maui, a two-CD/three-LP package that includes the free Maui concert at the foot of the Haleakalā volcano on July 30, 1970, in its entirety, arrives the same day.)

On Wednesday (Nov. 18), the GRAMMY Museum will host an exclusive premiere of Music, Money, Madness as part of its COLLECTION:live programming. The event will also include a live panel discussion featuring some of Hendrix's closest family members and associates, including younger sister Janie Hendrix, former bassist Billy Cox, engineer Eddie Kramer and McDermott.

Ahead of the premiere, GRAMMY.com caught up with director John McDermott to discuss his personal Hendrix history, his insights on Music, Money, Madness … Jimi Hendrix in Maui, and why, 50 years on, the groundbreaking electric guitarist's music still resonates.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//jUwvRQv77HA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Before we talk about the documentary, I'm curious how you landed this dream job as "keeper of the Hendrix vault" in the first place.

In the late 1980s, I was working as a writer, producer and a director on various music projects. I was always fascinated by the Hendrix story. I had previously written about him for a major music magazine, and that opened up a friendship with Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer. From there, we worked on a book together, Hendrix: Setting The Record Straight, which came out in 1992. It was not a traditional biography. We presented Jimi through the eyes of those closest to him.

The idea of a tribute album came next [Stone Free: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix]. Released in 1993, the record featured artists like Seal, Buddy Guy and Eric Clapton. Some proceeds went to a United Negro College Fund scholarship fund created in Jimi's name.

Shortly after, Eddie heard Jimi's father [James Al Hendrix] was involved in litigation over the ownership of his son's legacy, including the rights to Jimi's music, name and likeness. The Hendrix family asked me to help. Eventually, Al was victorious and all rights were returned to the Hendrix estate. That's when Al asked me to manage Jimi's music catalog. It's hard to believe that was 25 years ago. Since our first archival releases of unreleased Hendrix music in 1997, our mission has remained the same: keep Jimi in front of as many fans as possible. As a fan myself, I only came to truly appreciate Hendrix after his death … I never saw him live. For me, he was always this extraordinary artist with a fascinating story.

Speaking of fascinating stories, Music, Money, Madness … Jimi Hendrix in Maui certainly fits the bill. It's a captivating tale of a strange yet seminal time for the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

What makes this show so fascinating is its uniqueness. Three weeks before he was playing to 500,000 [people] at the second Atlanta International Pop Festival. Then, he arrives on Maui to play for 700 people seated by astrological order at the side of a volcano … that was something only Jimi could do.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//zv97c3W6lw8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Why did you decide to tell the story of the making of Rainbow Bridge and the Jimi Hendrix Experience's Maui sojourn in the summer of 1970?

We've told the arc of Jimi's story before: from birth to death in Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child [2010]. In other archival releases, we've examined temporal moments such as the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock.

The Maui performance is always one fans request the most. With this film, we wanted to drill down and recalibrate what this whole thing represented. If we were going to do it, we wanted to do it in a way that provided the context for this story and share all of what exists of film—using the complete concert performance at Haleakalā to tell the real story. Rainbow Bridge was clearly not a Jimi Hendrix project, but it only could have taken the form it did with him dying. Had he lived, it never would have taken this form. Maybe it might have been just an instrumental score for a surfing documentary … no one really knows.

Since Jimi died in September, less than two months following these concerts, the Rainbow Bridge movie and accompanying soundtrack played a larger role in Jimi's initial posthumous legacy. With this movie, we want to reframe that story.

How did you reframe the story to specifically focus more on Jimi's story and the free Haleakalā concert?

First, we recovered original footage from Jimi's time in Maui. This documentary was more about extracting that new footage and providing fresh context. In Rainbow Bridge, there [were] only 17 minutes of performance footage that was haphazardly put in the movie. Mitch [Mitchell] had to overdub his drums at Electric Lady Studios just to save the audio.

Read: Jimi Hendrix's 'Electric Ladyland' Turns 50

At the same time, you wanted to present an objective story, correct? How did you achieve this balance?

Definitely. You get the Hendrix side of the story listening to new interviews with surviving bandmates Mitchell and Billy Cox; Warner Bros. record executives; his engineer, Eddie Kramer; and others close to Jimi. We chatted with some of the original participants in the movie and included interview clips with [Rainbow Bridge director] Chuck Wein to tell their side.

Fans need to understand how this chapter in Hendrix's career became blown up because of his death. To hear his bandmates talk about that time in Maui … that fascination that attracted me decades ago happens anew for kids around the world who appreciate the phenomena that was Jimi Hendrix. Take the Beatles film Eight Days A Week. Those who lived through that understand about the girls screaming at their shows—the tsunami and energy about the creation of that music—but that movie showed a new generation of global audiences what The Beatles really meant. In the same way, you can't fathom how amazing Jimi was until you see, hear and learn more about him.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//qFfnlYbFEiE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Why now? Did you plan the film's release to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Hendrix's death?

Not at all. Restoring the footage and the original audio took time. This is a project we had on the broiler for quite a while. We wanted to take time to get it right and speak to the right people. There is a temptation sometimes to get the easiest folks to speak, but often these people don't shed the greatest light on a subject. Originally, we had hoped to screen it at the Maui Film Festival this past June, but because of the pandemic, that didn't happen.

Why, a half-century since the electric guitar innovator and Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award recipient died, is the Hendrix legacy still important to preserve?

First, Jimi alone keeps his legacy alive. He is the guy who does the heavy lifting. Why is his legacy still so important? Compare it to what people would give to hear just one more wire recording from Robert Johnson. Because Jimi died so young, he left so many questions unanswered. Every one of these projects we release is another clue to that puzzle, from both a sonic and a visual perspective. Hendrix's appeal [resonates] with young people and remains with original fans. They, along with a growing global audience, see him as an ongoing touchstone: No matter the country where they are from, their gender, their race or their age … something about Jimi cuts right through.

'Band Of Gypsys': 5 Facts About Jimi Hendrix's Final Living Release | GRAMMY Hall Of Fame

Ace Of Cups

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

news

Fame Eluded The Ace Of Cups In The 1960s. Can They Reclaim It In 2020?

The all-female psychedelic band petered out before making an album. Now, as senior citizens, they’re sharing their second via GRAMMY.com — and they have one hell of a story to tell

Mary Alfiler was in the middle of a rough patch when she found a poem about death written on a bar napkin. "We thank with brief thanksgiving / Whatever gods may be, That no life lives forever / That dead men rise up never / That even the weariest river / Winds somewhere safe to sea,” one verse read. She didn’t know it then, but those words were from “The Garden of Proserpine” by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

At the time, Alfiler — then Gannon — just knew it meant something to her. It was 1971, she was a single mother on food stamps, and her band, the Ace of Cups, was hanging on by a thread. Still, Swinburne’s poem, which she found at the Sleeping Lady Café in Fairfax, California, became the germ of a new song, "Slowest River," which flips the theme of death into one of renewal and return to one's life-source. Forty-nine years later, the stirring piano ballad concludes Sing Your Dreams, a new record by the Ace of Cups. On that track, Jackson Browne shares lead vocals with founding member Denise Kaufman.

Confident, joyful and eclectic, Sing Your Dreams follows the band’s 2018 self-titled debut. The album features reworkings of Ace oldies, like “Waller Street Blues,” and “Boy, What’ll You Do Then”; a trippy devotional to the Feminine Divine (“Jai Ma”); and a fiery call for female leadership (a cover of Keb’ Mo’s “Put a Woman in Charge”). Before it’s released Oct. 2 via High Moon Records, check it out exclusively below via GRAMMY.com.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/kG4r-M0jgUE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Back in the 1960s, the Ace of Cups shared stages with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Big Brother and the Grateful Dead. While they may not appear in biopics and on blacklight posters, the Ace of Cups have something ultimately sweeter than public adulation. Unlike their old associates Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jerry Garcia, who all died too young, the Ace are happy, creative and healthy in their autumn years.

Before the Ace of Cups, hardly anyone had heard of an all-female rock band. In that way, they paved the way for the Runaways, the Go-Go’s, the Slits and so many others. Despite having the talent, the drive and the charisma, the Ace of Cups missed the major-label feeding frenzy that gobbled up many of their Bay Area peers.

Which may have been for the best, they say. "If we had gotten signed, things might have played out differently, Alfiler says. "Knowing me and knowing the way we were acting, we might have gone the way of a lot of bands.”

"A lot of bands that we played with and musicians we loved aren’t even on Earth anymore," Kaufman tells GRAMMY.com. "We’re grateful to all not only be alive but be alive and up for playing."

But as septuagenarians, the Ace of Cups has been given an unlikely second chance in the music business — and they’re seizing it.

Hear Every Sound

From an early age, each Ace member had musical impulses that they struggled to manifest in an uncomprehending world. Alfiler, their bassist and a native of New York state, sang in a girls’ choir that performed Gregorian chants and Irish reels. She longed to play an instrument but hadn’t received piano lessons, and the guitar was out of the question. "I’m not complaining; I’m so happy about my vocal training," she tells GRAMMY.com. "But what opportunities were there for me?" Alfiler went to college out west in Monterey, where she joined a theater group.

Mary Mercy (née Simpson), their lead guitarist, loved Joan Baez and won first prize at a high school talent show for her renditions of "Silver Dagger" and "Banks of the Ohio." In 1964, while attending San Jose State, she saw the Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen play at a coffeehouse owned by his bandmate Paul Kantner, and Kaukonen agreed to give Simpson guitar lessons. "I abruptly left San Jose State, so I never did pay him [for the last lesson]," Mercy tells GRAMMY.com with a laugh. (She’d reimburse him two years later.)

After her lessons with Kaukonen, Mercy functionally learned lead guitar backward. "Most guitar players I ever met would copy every guitar player they heard," she explains. "In a song, I would play whatever notes, but sometimes the notes wouldn’t sound right. So I learned the scales sort of by trial and error. Looking back, I think that was probably a mistake because you have to learn from what other people have done."

Of all their backstories, Kaufman’s is the most bonkers. In her freshman year of college, she was Merry Prankster, traveling on the bus with countercultural figures Neal Cassady (of On the Road fame) and Ken Kesey. Under the name Mary Microgram, she appears several times in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe’s 1968 document of the Pranksters’ hallucinogenic sojourns. “At last Kesey returns with the last to be rescued, Mary Microgram,” one passage reads, “looking like a countryside after a long and fierce war.”

"Neal was tuned in on such an amazing level," Kaufman says. "I’d ride shotgun with Neal and close my eyes. It wasn’t like you were in your thoughts, and he was in his thoughts. He was a weaver, a combiner of consciousness." Soon after Kaufman got off the bus, she sang in a band called Luminous Marsh Gas, which later evolved into Moby Grape.

During her freshman year at UC Berkeley, Kaufman met future Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner and shepherded him through his first acid trip. "I thought it wasn’t a good idea for him to do that himself with no experience," she says. The pair bought a Sandy Bull record, went to his house, and he did the deed. Kaufman and Wenner eventually dated and were briefly engaged until she, in her word, "bailed."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/mqP6npBuZuI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Wenner partly inspired Kaufman’s first solo single, "Boy, What’ll You Do Then," which would become an Ace calling card and appears on Sing Your Dreams. (There are only two known copies of the original 45, one of which recently sold for $10,000; the masters went up in the Oakland fire of 1991.)

Growing up with a white father and a Black stepmother, Ace keyboardist Marla Hanson (née Hunt) was exposed to gospel music and R&B. "I came from a musical family. Everyone played an instrument and sang," she wrote on her website. I’m told that the first song I learned on the piano was Brahms’ ‘Lullaby,’ and by the time I was eight, I had taught myself the first two movements of [Beethoven’s] Moonlight Sonata by listening to a 78 record."

Ace drummer Diane Vitalich got her musical itch watching marching bands. "I could hardly see the drummers’ strokes because they were moving so fast," she tells GRAMMY.com. "They had a little music class in grammar school, and I told them I wanted to play the drums. They said, ‘No, you’re a girl. Girls don’t play the drums.’ I wished I was a boy because my brother could do all these different things I wasn’t allowed to do."

Photo by Casey Sonnabend

The Ace Begins

Alfiler and Hanson were the first two members of the Ace to play together. (Alfiler’s last band was the Daemon Lover, which she joined "because I thought the guitar player was cute.") "Forming an all-woman band was Mary’s idea," Hanson stated in the liner notes of the band’s 2003 odds-and-ends collection It’s Bad For You But Buy It!. "She just talked about having a band like it was the most natural thing in the world."

At this point, the concept for the band was amorphous, even crossing over into performance art. Alfiler once considered wiring up her college friend Val Risely with bird wings to soar over the audience to the folk song "The Cuckoo." One night in 1966, while party-hopping in Upper Haight, Alfiler met a kindred soul and the next member of their nascent band.

"I just wandered into one of these Victorian houses on a side street," she remembers. "They had all the Zig-Zag papers they’d licked all night long to make crepe paper decorations." In one room, she found a girl bashing a drum kit all by her lonesome. That girl was Vitalich, and Alfiler invited her to come over and jam. "It was a very innocent thing," Alfiler says. "We had no image of what we were doing." After transferring from San Jose State for San Francisco City College, Mercy heard through mutual friends about Alfiler and Hanson, called them up, and came over to jam.

Kaufman was the last member to join. At the time, she lived in the psychiatric wing of Mount Zion Hospital, where her parents had committed her due to her LSD use. Before acid attracted rough publicity, Kaufman’s parents were open to it, going as far as to schedule a therapist-supervised psychedelic experience with her. (That therapist, Dr. James Watt, went on to be arrested for possessing 300 milligrams of liquid LSD on his yacht.)

Upstairs at Mount Zion, she met the eccentric beatnik and band manager Ambrose Hollingsworth Redmoon, who had been rendered paraplegic by a 1966 car wreck. As per a family therapy program, Kaufman could keep an organ, a guitar and an amplifier in her room. She could also breeze in and out as she pleased.

On New Year’s Eve 1966, Kaufman attended a party at the proto-metal band Blue Cheer’s house in the Haight. "I wandered upstairs, and that’s where I met Mary Ellen," she says. "I always travel with at least an A harmonica in my purse or pocket in case some guitar player is playing blues in E." Which is just what Mercy was doing, and the two women began to jam.

The five women played together for the first time at Alfiler’s and Hanson’s pad at 1480 Waller Street. "I’ll never forget when [Denise] walked in," Hanson said in a 1995 interview. "She’s wearing cowboy boots, a very short skirt, a wild fur coat and a fireman’s hat. Her hair’s stickin’ straight out on the side. She’s got these big glasses and this big guitar case — she’s like 5’ 3, and it’s almost as big as she is. Even in San Francisco, she stood out."

The fivesome wrote their first song, "Waller Street Blues," about the realities of bohemia in the Haight. "That funky blues described, with a few exaggerations — our life at the time," Alfiler says. No bread, lousy food and a pot bust next door." There was no template for what the five women were doing: the Ace was simply a raw expression of creativity and camaraderie.

"All the social mores about what you were supposed to do, like get a boyfriend, were all out the window," Alfiler says. "It was a brave new world, and we didn’t know where it was going." Even Kaufman admitted to being skeptical: "I couldn’t imagine women playing like that. I’d never seen a woman kick ass on the drums," she says. "I knew there were jazz bands with women and all that, but I’d never seen any women play the kind of music we were playing. I had no context."

As part of the deal with Mount Zion, Kaufman ran the office and did PR at Fantasy Records, taking the bus there every day from the hospital. One of her co-workers was a young John Fogerty, then in the pre-CCR band the Golliwogs, who worked in the vinyl packing room. Upstairs were senior partners Max and Sol Weiss and junior partner Saul Zaentz.

Max Weiss helped the Ace rent their first real gear from an Oakland music shop and let them and the Golliwogs practice at the Fantasy headquarters three nights a week. Hollingsworth became the band’s manager. One night, while the nameless band sang around Hollingsworth's bed, he pulled a Tarot card and passed it to each member. It was the Ace of Cups, which depicts a divine hand holding a cup with five streams of water flowing forth.

The women saw the five streams as representing themselves. As such, the Ace of Cups had a name and a band prayer, which they recited in a circle before every practice: "May the Ace of Cups overflow and fill the world with happiness."

Because he was physically indisposed, Hollingsworth, who also managed Quicksilver Messenger Service, handed the reins to Ron Polte. Polte had been enamored with the Ace ever since he saw them at the Continental Ballroom in Santa Clara in early 1967. “I heard their little tinkling voices, went over and saw all these beautiful women playing music,” Polte remembered in It’s Bad For You But Buy It!’s liner notes. “So at the end of the show, when I was paying Denise, I said, ‘You know, you guys are great.’ And she gave me a big hug and a kiss and said thanks.”

Because the Ace didn’t have an album, promoters had to consider them on face value. “When we were first looking for gigs, Ron called the Peppermint Lounge on Broadway, and the manager said ‘An all-women band? Yeah, we’ll hire them.’” Ron said, ‘Well, do you want them to come in and audition?’ The guy goes, ‘No, no. We’ll hire them, but we want them to play topless.’ Ron called me afterward, and I said ‘Well, we’ll play naked, but we won’t play topless!'"

At their house on Autumn Lane looking toward Mount Tamalpais, the Electric Flag shared the band’s equipment and invited them to their "coming-out party" at Monterey Pop Festival. Vitalich didn’t go, and Kaufman rain checked because she had a sitar lesson that Monday. But Alfiler, Mercy, and Hanson went, and they returned raving about a dazzling new guitarist: Jimi Hendrix.

"We were in their motel room, and I was in the bathroom, just combing my hair or whatever. The window was open, and I heard this guitar player. I go to Mary [Alfiler] and say, ‘We have to go there right now. We have to see who that is!’ We rushed over, and it was Jimi Hendrix playing." One week later, Polte got a call asking if the Ace of Cups would open for Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Panhandle in Golden Gate Park.

Hendrix watched the Ace and became their most high-profile fan, asking if the Experience could use their equipment and running around during their set taking pictures. Sadly, the Ace never got to see them. (“I’ve never seen any photos taken by Jimi Hendrix,” High Moon founder George Wallace remarks.)

Mercy was perturbed by Hendrix’s guitar antics but charmed anyway. "My guitar teacher Namoi Healy had always told me ‘Whenever you play your guitar, when you’re done, put it in its case. Don’t take it to the beach. Take very good care of your guitar,’” she says. “So when he burned his guitar, I thought he must have flipped out or something. I couldn’t fathom it!"

That December, Hendrix raved about the girls to Melody Maker. "I heard some groovy sounds last time in the States, like this girl group, Ace of Cups, who write their own songs and the lead guitarist is hell, really great." To be praised by Hendrix means a guitarist has reached the top of the mountain — a notion that makes Mercy laugh long and hard.

"I just wish, in some ways, that he had just said ‘The Ace of Cups were a great band,'" she demurs. "I don’t think my guitar playing was up to what he said it was. I think he was just being nice."

Later in 1967, the Ace set up their practice space at a hangar in the Sausalito heliport. Word was getting out about the Ace of Cups, and a few potential deals materialized. One day, Capitol Records stopped by the heliport. "They had to leave fast. They said, ‘You have five minutes to play us something,'" Vitalich says. "The song we chose may not have been the best one for them to get who we were. They thought ‘Eh.’ They weren’t that interested."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/oLmHLNX2kdE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Cracks In The Cups

At this point, the Ace of Cups had friends in high places. In 1968, they sang backups on Quicksilver Messenger Service’s “The Fool,” a nearly sidelong jam from their 1968 debut. (They’d later do the same on Jefferson Airplane’s 1969 album Volunteers.) Despite their rising profile, the pressure was mounting to put down their guitars and focus on family. “It was always a dilemma when we were thinking about it,” Kaufman says. “If we got a chance to do that, how would we pull it off?”

Hanson and Alfiler had babies at this point; Hanson’s daughter Scarlet Hunt had been born in April 1968, and Alfiler’s daughter Thelina Allegra arrived on Valentine’s Day 1969. While they had nannies to watch the babies during practices, being away from them on tour was virtually impossible. While Alfiler was nursing Thelina, she had to leave for Chicago to play a festival without her. "That was painful for her," Kaufman says.

“One of the hard things for us which freaked us out whenever we got close to signing a record deal,” Kaufman said in the It’s Bad For You But Buy It! liner notes, “was that in those days, you had to promise that you would tour. So when we began to have kids, it was such a dilemma… they were offering so much money, but it was hard. Even us just going away for short trips was difficult for the babies.”

Friction developed between Kaufman and Hanson. “Marla and I had some difficult times working together,” Kaufman says. “We could spark off each other and write well, but my experience with Marla was that she was volatile, and I could never count on what might happen. That was hard for me. She was a real talent and had wonderful musical gifts, but I never knew if she would give them or withhold them.”

Meanwhile, Polte’s agency West-Pole, which also booked Big Brother and Electric Flag, was, in Alfiler’s words, “disabling themselves” in a cocaine haze. “The drug scene was starting to be pretty bad,” Mercy says. “It was disheartening and just seemed dirty. That bothered me. I used LSD for sure, and I smoked pot, but I didn’t do these harder drugs. I started feeling like I needed to get out of this whole scene.”

At the time, Mercy was in a relationship with Francis Roth, who managed the Bay Area rock band Sons of Champlin, and domesticity was on her mind. “I started feeling like what I was supposed to be doing was having a family and living a life in that way,” she says. “There was a cultural impression of what I should be doing. There was arguing going on. I decided, ‘I don’t need this.”

In 1969, Mercy became the first to leave the Ace. (That fall, she returned briefly for one gig.) “Without [Mercy], it wasn’t the same ever again,” Hanson said in the liner notes. “I got more and more depressed as the weeks and months went on… we had all worked so hard for so many years and still had nothing to show for it.”

That year, Kaufman, who was five months pregnant with her daughter Tora, was shoulder-to-shoulder with 20,000 people at the Altamont Free Concert when a 32-ounce beer bottle landed on her head. The bottle cracked Kaufman’s skull, requiring emergency neurosurgery to remove shards of bone from her brain. If the doctors had used anesthetic, she would have lost her baby. (Over Zoom, Kaufman lifts her hair to show the quarter-sized dent in her head. Today, Tora lives on her Kauai farm and co-owns the music shop Hanalei Strings.)

The following year, the Ace of Cups got their only authentic offer from Saul Zaentz at Fantasy Records. Given this is the same Zaentz, who later sued John Fogerty for performing his own songs, one can imagine how this went down. “They sat down, and they wanted all our publishing!” Kaufman says, and Fantasy made a paltry offer that Polte refused.

Hanson soon exited the band. To fill the void she and Mercy left, three men temporarily join the Ace of Cups — Kaufman’s then-husband Noel Jewkes on horns, guitarist Joe Allegra, and drummer Jerry Granelli on an occasional second drum kit. By 1972, the Ace had evaporated completely. “I wouldn’t say it was a breakup. We just kind of faded out,” Vitalich explains. “The five of us just kind of drifted apart.”

What'll You Do Then?

That year, Alfiler and her baby daughter Thelina flew to her bandmate Denise Kaufman’s house on Kauai with 11 pieces of luggage, including a sitar and tamboura wrapped in blankets. She ended up staying on the island permanently. At that point, Vitalich and Jewkes lived in converted chicken coops outside Kaufman and Jewkes’ house on Creamery Road in San Geronimo Valley. ("There weren’t any chickens in it," she clarifies.) When that living situation ended, Vitalich moved into a tent on the next-door neighbors’ property, where she kept a queen-sized bed, a rug, a dresser and her drum pads.

Vitalich briefly played in the band Saving Grace with Hanson, the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart, Quicksilver’s David Frieberg, and singer Cyretta Ryan, which rehearsed for months, played one gig, and called it a day. Alfiler and Kaufman soon moved to a house in Novato with a woman named Joellen Lapidus, who built ornate dulcimers for Joni Mitchell.

In 1974, Alfiler returned to Marin County for a year; she met her husband Andy on Kauai, he joined her back in California, he returned to the island, and she followed him. She had five more children, taught music at Island School in Kauai, and played in church and local bands. For a year and a half, Alfiler and Kaufman played in the all-women band Tropical Punch, which played at Club Med in Hanalei. But for a while afterward, the two didn’t see much of each other.

“That’s the house where I remember working with Mary Gannon on ‘Slowest River,’” Kaufman says. “When I went to Kauai, I left everything there because I thought I’d be back in a few weeks. I left everything and took my pop-tent, a dulcimer, and my baby.” That Thanksgiving, Alfiler arrived by plane with the remnants of the band.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/nkwcNE1aXfg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In 1972, Mercy lost her son Kodak at 22 months old from a heart condition, a tragedy Alfiler alludes to in the song "Macushla." "At that point, I got into all kinds of spiritual ideas because I kept thinking, ‘What’s the point of life?’ I had a baby die, and I was young,” she says. She attended a three-day Tibetan Buddhist retreat and underwent a series of initiations, including fasting from food and water for a full day. "I remember thinking, ‘I can’t do this. This isn’t for me,'" Mercy says.

For the next 13 years, Mercy, her then-husband Roth and her two children lived rent-free on 120 acres of land in Willow Creek, halfway between the California coast and where she lives now in Weaverville. “That’s where I learned how to can food,” she says. “We had eggs; we had chickens. We had bees; I had a bee suit and gathered honey. It was the back-to-the-land movement, which was one of the things that happened during the ‘60s.”

While in Willow Creek, Mercy played in the country-western band the Cosmic Cowgirls, then moved to Arcata and played in the band Roundup (later called Still Pickin’) then-partner Dave Trabue. She worked in the Behavioral and Social Services department at Humboldt, then in a detox center, as a substance abuse counselor, and as a case manager for behavioral health services.

In 1983, Kaufman moved to a guest house in Laurel Canyon to attend the bass program at Musicians Institute. While in Los Angeles, she taught yoga to Kareem Abdul-Jabaar, Quincy Jones, Jane Fonda, Sting and Madonna. In a 1997 Rolling Stone profile, Madge sang Kaufman’s praises. “She was in one of the first all-female bands,” she said. “Have you heard of the Ace of Cups? They [played] with the Grateful Dead. I like to poke her brain, get information out of her.”

For her part, Hanson spent many of her post-Ace years as the pianist and director of Fairfax Street Choir, a collective she formed in 1972 from jam sessions at the Sleeping Lady. (Alfiler, Vitalich and the Monkees’ Peter Tork also had stints in the choir, which reunited in 2013 for a new album and performance at the Marin County Fair.)

Come the 1990s, “I was living in Hawaii, not connected to anything,” Kaufman says of the band, whose name was quietly bubbling up in music collectors' and historians' circles. She’d heard about Ace of Cups songs, like “Boy, What’ll You Do Then” and “Stones,” circulating among bootleggers under false band names and track titles. In 1997, Kaufman got a letter from Alec Palao, who ran a magazine about the Berkeley music scene, and the pair began a correspondence. Palao knew about their boxes of reel-to-reel tapes and wanted to release some of the music therein.

Palao listened to their assortment of rehearsals, live gigs, and demos and cleaned up the audio. Then, Kaufman tracked down the one collector known to own a copy of “Boy, What’ll You Do Then” and Vitalich came over with an ADAT recorder to capture the audio. Thus, this nearly-lost recording — and so many others — were included on 2003’s It’s Bad For You But Buy It!. One person who eagerly bought it was the eccentric George Wallace, who then was dreaming up his boutique reissue label High Moon Records.

Reading about Kaufman in the liner notes, “I thought ‘Well, this is somebody who knew everybody,’” he says. “Maybe she’ll know where there are some lost tapes from the Avalon Ballroom [or something].” Wallace flew to Los Angeles for dinner with Denise, came to her house, and the pair listened to music all night.

Wallace is still amazed the Ace wasn't successful in the 1960s. “I would think the fact they were all women — and so good! — would make record companies drool,” he says. “No one knows why exactly the Ace didn’t get signed to a record deal. To me, it’s astounding.” He encouraged Kaufman to do more with the Ace and gauge the other members’ interest in continuing it.

An Unlikely Reunion

In 2011, the five original Ace members reunited to perform for Wavy Gravy’s 75th birthday celebration in support of his Seva Foundation. “The reason we could do that show was that George rented us a house and a rehearsal space,” Kaufman says. “It was only because of George’s support that we could do that.” Due to personal differences, Hanson didn’t join the other members for future performances.

About a year after Wavy Gravy’s party, Vitalich, Kaufman, and Mercy began flying to Marin County to jam together. (At that point, Alfiler, who lived 3,000 miles away, “wasn’t in with two feet at all,” Kaufman says. “She was interested, but she wasn’t committing to be part of it. Eventually, she did.”) In 2015, after discussing the matter with Kaufman, Wallace decided to help the Ace make the debut album of their dreams.

And he was the man for the job, Kaufman says. “When he listens to music, he hears things I certainly don’t hear and has such interesting ideas. He believes in artists and artistry. And who else would take a group of women in their seventies and say ‘This music needs to be heard?’”

With Vitalich’s old collaborator Dan Shea behind the boards, the band entered Laughing Tiger Studios in Marin County sans Hanson. “My first thought was ‘What would this record have sounded like if they had recorded it in 1968 or 1969?’” Shea tells The Recording Academy about the experience of recording 2018’s Ace of Cups. “We tried to get the most vintage sound possible, which is harder than you might think.”

On Ace of Cups, Shea ultimately went more George Martin than Nuggets, giving songs like “Pretty Boy,” “Taste of One,” and “Stones” the lavish production he felt they deserved.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/6KqPCFw-VHQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

The Ace of Cups had their record release show in 2018. Soon after, their new manager Rachel Anne — who the Ace calls their “un-manager” due to being unmanageable — took the septuagenarians on a West Coast tour. At the time, Shea filled in on the keyboard but didn’t want to commit to touring. Dallis Craft, a Bay Area musician who is more than a dozen years the others’ junior, stepped up as their fifth member.

Photo by Jamie Soja

"I’ve always been a scrapper, making my living making music,” Craft tells GRAMMY.com. "I guess people floated my name around." She sees herself as the glue between the larger-than-life personalities in the Ace. “I’m just a happy first mate or whatever. Just tell me what to do to facilitate this whole thing, and I’m there. They’re strong. And it’s so good for me to be around strong women because I’m not.”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/POUghoLOC60' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In February of 2019, the Ace played at the Mercury Lounge and Rockwood Music Hall in New York. That November, they returned to perform on The Today Show. “That was the biggest gig,” Alfiler says. “The big time, right? I met all these people, normal people with headphones on, running around. Everything’s on time; the makeup is downstairs. Maybe in my 20s, I would have thought it was the cat’s meow, but now it’s like ‘Thank you for doing this because I know what it is. It’s so hard.'"

“They schlepped all their gear,” Rachel Anne says. “We sometimes fight because they do shit and I’m like ‘‘Could you please not touch anything? We have roadies.’ I would go in with a load, come back, and there they’d be, like a trail of ants, carrying their gear. They’d say things like ‘Rachel, we’ve been schlepping our gear for 50 years! Back off!’ I’m like, ‘I can’t let anything happen to you!'"

Singing Their Dreams

For Sing Your Dreams, Shea adopted what he calls "a more contemporary approach." "There are more songs that they’ve written in the past 20 years as opposed to 50 years ago,” he says, despite two of the first songs they ever wrote, “Gemini” and “Waller St. Blues,” popping up on the tracklist. “I would say it’s less produced than a lot of the songs on the first record.”

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/s2E8LpjhnDA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Kaufman calls “Jai Ma” a “sort of Latin, sort of African, sort of Sanskrit, sort of Yogic dance to the feminine.” “It’s looking again at the story of Eve and the apple,” she explains. “In many cultures and traditions coming from patriarchy through thousands of years, women are kind of blamed or demeaned or made nameless. She brings up the story of Siddhartha, specifically his harem of women from whom he flees in disgust: “I always wondered when I heard that story, ‘What are their names? What do they want?’”