The legend of Jay-Z's 13th solo studio album preceded the actual work.

Following 2014's "Elevator Gate" and Beyoncé's candid GRAMMY-winning project Lemonade, rumors swirled that Hova would release his own album in response.

Once the New York City buses with 4:44 emblazoned on the sides started rolling around in late spring 2017, speculation ran rampant about the title being informed by the incident — a hotel elevator camera capturing Solange attacking him as Beyoncé looked on. (The address of Le Bain, the hotel's rooftop bar, is 444 West 13th Street. Meanwhile, Jay-Z's favorite number is 4.)

Just how intimate was Jay-Z planning to be?

On June 30, 2017, we found out.

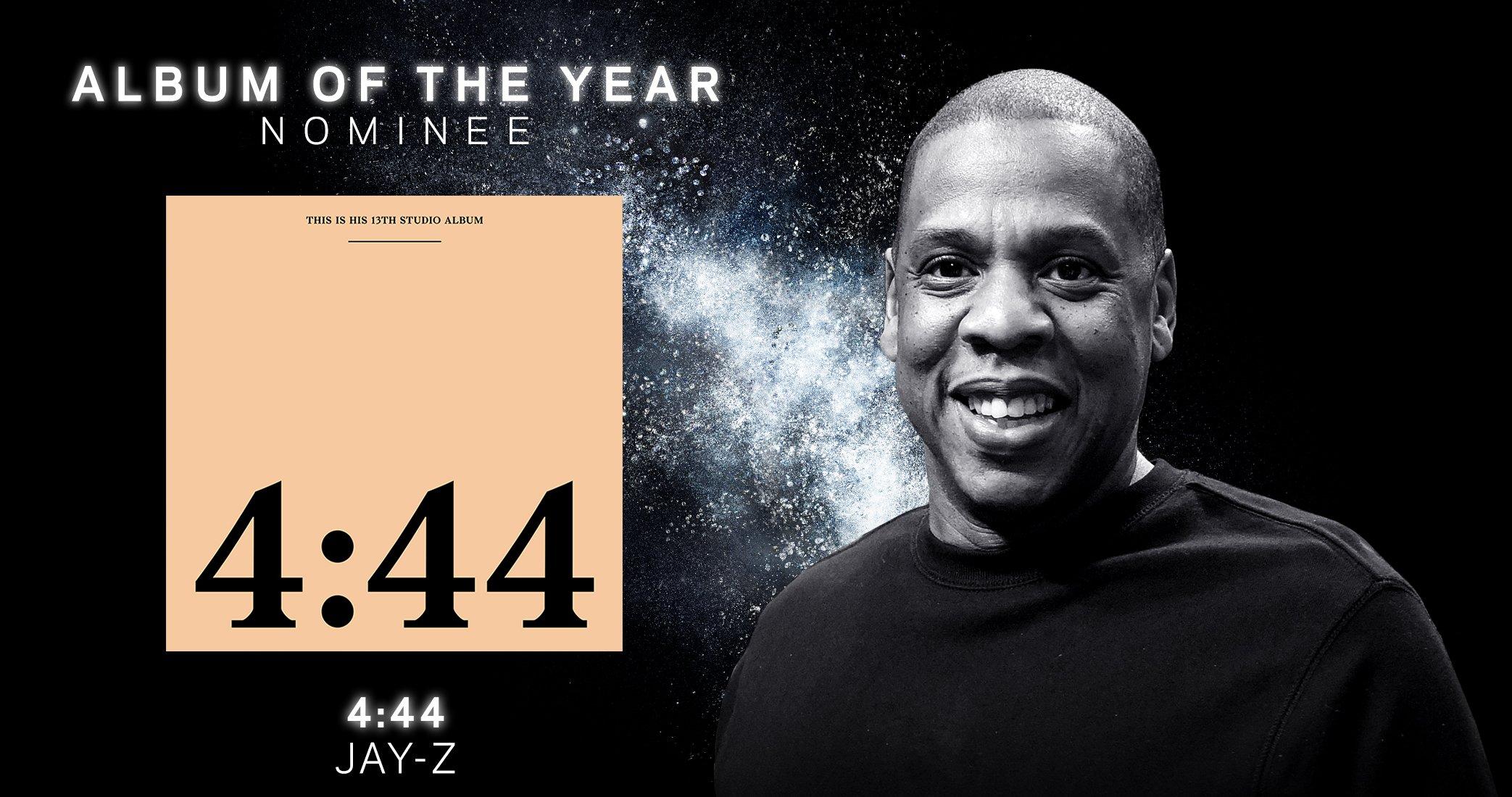

4:44 is much more than the sum of its parts. On one hand, it's the quintessential one artist/one producer masterpiece, as Jay and super producer No I.D. pieced the LP together (with famed engineer Young Guru) until perfection was achieved. On another hand, it's a coming of age project for not just Jay-Z, but hip-hop in general. 4:44 travels beyond the ageism crossroads rappers have often reached and lost their way. Jay-Z proved that grown rap music can exist and punctuated it by being an open book and stripping away his mystique. He admitted past sins, acknowledged failures (for perhaps the first time in two decades) and the result was his most personal project to date — yielding eight 60th GRAMMY nominations, including Album Of The Year.

<iframe src="https://tools.applemusic.com/embed/v1/album/1256675529?country=us&itscg=30200&itsct=afftoolset_1" height="500px" width="100%" frameborder="0"></iframe>

No I.D., Jimmy Douglass, Chaka Pilgrim and other key participants revisit the making of the album and how the magnum opus came together.

*Jay-Z (artist/co-producer): Before I started this album I studied — not just hip-hop — any genre. I studied Prince, I studied Mike [Jackson], Bono had "Beautiful Day" [when] he was like 40, I think. Just like from the beginning of someone's career, and that sort of album that really means something that touches the culture. The touchpoint that moves, that starts a conversation, and be really f***ing good. It's a hard thing to do because you're so removed from where you were at the beginning.

No I.D. (producer): We had discussed this type of project for a couple years. When he first came to me — two, two and a half years ago — he told me he wanted to do something that was a little more revealing. I think at the time I didn't have a sonic direction; he didn't have a sonic direction. It kind of led to us running back and forth into each other. I really was just trying find something sonically to do that would be different, but familiar.

*Jay-Z: No I.D. came to me with a technique. He said, "I got this thing. … I got your next Blueprint. … I know that's a lot to say."

No I.D.: I told him, "I got something," and played him tons of beats that kind of had the technique, and some of the stuff we ended up using was in that batch.

*Jay-Z: We were at the Roc Nation offices here in L.A., and he played me what he was working on, and I was like, "That's amazing."

"4:44 was putting all of the marbles on the table on every front — between the home front, the fan front, all of it. It's like, 'Here it is: all or nothing.'"

No I.D.: As we began to actually hone in and work and [Jay-Z] knowing I had the specific technique, I was like, "What direction do you want to go in?" He had a playlist, and he was saying, "This is what inspires me at this moment." I was like, "Give it to me and let me work off this template, so to speak."

Ron Gilmore Jr. (keys/bass/vocoder): When I came in, a lot of the samples were already done — a lot of the drums were already done, and what I was doing was embellishing, maybe adding a bassline here or there.

No I.D.: For the majority of the time it was me, [Jay-Z], and [Young] Guru, and it would either be at my studio or his house, which automatically made it super intimate. No one knew that we were even doing it. So once he made an announcement — if we really got going in January, then he kind of walked in by April and told everybody "Hey, I've got an album." And it was out by June.

Dave Kutch (mastering engineer): It was pretty close to the release date that we did everything. It all happened very, very fast.

Jay-Z: We kind of moved on the fly because in the beginning, I wanted to drop the title — which we did, we put the 4:44 all around on buses and on billboards.

Will Perron (creative director): We went back to the old way of doing things — billboards and posters and subways.

*Jay-Z: By the night it was like on the Channel 11 News everywhere. CNN was like, "I think Jay-Z is dropping an album." I dropped the billboard and it got figured out in 24 hours, and I was like OK we've got three more weeks.

Jimmy Douglass (engineer): The nature of it was quite simple: There's only one surprise element, one time.

Chaka Pilgrim (video producer): Jay came up with the deeper meaning of the songs on the project overall, and we kind of figured what was the visual accompaniment to it. We wanted to do something that was non-traditional, not music videos but a little more esoteric that allowed you to put yourself in the place of [Jay-Z] in being honest and open on where that can lead.

Kutch: The first song I worked on was "Kill Jay-Z," and I was like "Oh my god." It was similar to the first time I got to listen to Lemonade entirely when I mastered that. When you heard the full lyric, and you heard the full storyline. It hits you like a ton of bricks. This much honesty. This much difficult honesty coming through in a project. It shows you why Jay-Z is Jay-Z.

<iframe src="https://tools.applemusic.com/embed/v1/song/1256675686?country=us&itscg=30200&itsct=afftoolset_1" height="110px" width="100%" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Douglass: At first I was like, "This is an amazing piece of work. It's amazing that he can actually be able to bare his soul and be able to apologize to his wife for his ill behavior. This was a really unique way of doing that, and it's amazing that he's in a position to have a platform like this to do that instead of bringing roses and chocolate home." That was my first impression. As I listened more, I was like, "He's saying some real s***." I was blown away.

Jay-Z: I've never been so open for so long; usually it's been one song, two songs, three songs on an album — then it's sprinkled in other songs. But for an entire album, to make 10 "You Must Love Mes" is new and kinda makes people uncomfortable.

Pilgrim: It's like the song ["Kill Jay-Z"] says, "You can't heal what you never reveal."

<blockquote class="twitter-tweet" data-lang="en"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">4:44. WOW. MASTER TEACHER.</p>— Kendrick Lamar (@kendricklamar) <a href="https://twitter.com/kendricklamar/status/880861466227757056?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">June 30, 2017</a></blockquote><script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>

Perron: Originally, we'd thrown some ideas around about what the album was going to be called. It was meant to be this really stripped away record, very didactic and super honest. We threw around ideas of doing like these grotesquely honest photos, and throughout the exploration of this — and the record was getting closer and closer to being done — it seemed obvious that "4:44 was the lead song on the record and what the record was anchored on. We landed on that being the title."

Douglass: I was awestruck by what he was doing and the courage that he had. It was putting all of the marbles on the table on every front — between the home front, the fan front, all of it. It's like, "Here it is: all or nothing."

*As told to Rap Radar podcast

(Kathy Iandoli has penned pieces for Pitchfork, VICE, Maxim, O, Cosmopolitan, The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Billboard, and more. She co-authored the book Commissary Kitchen with Mobb Deep's late Albert "Prodigy" Johnson, and is a professor of music business at select universities throughout New York and New Jersey.)