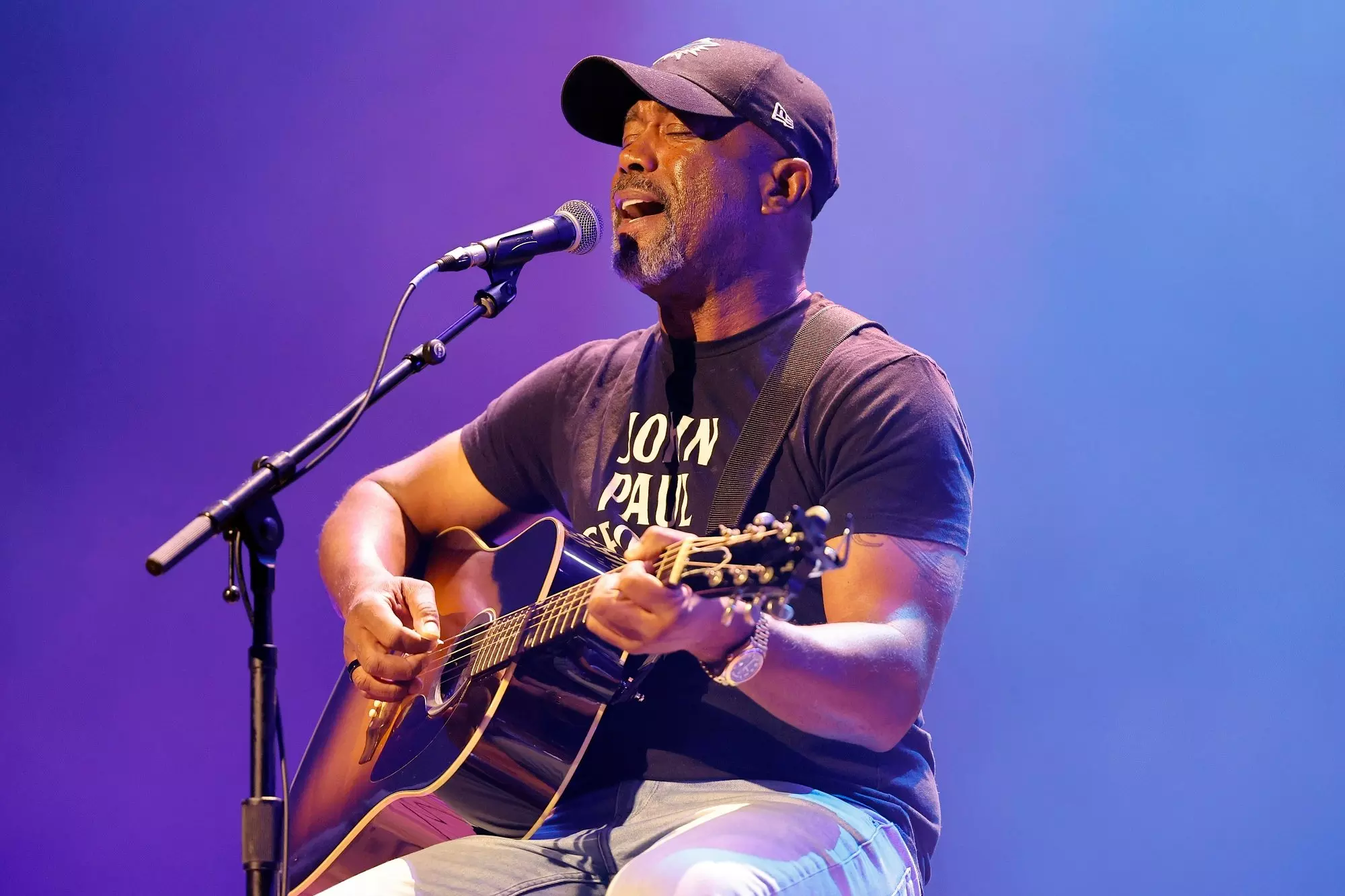

Photo: Ismael Quintanilla III

Son Volt

news

Jay Farrar On Son Volt's New Album 'Electro Melodier' & The Lifelong Draw Of Electric Guitars, Words & Melodies

During the pandemic, Jay Farrar had more time than ever to craft Son Volt's new album, 'Electro Melodier.' The result is among the 30-year-old band's most personal, oracular and muscular works to date

When the Americana heroes Uncle Tupelo broke up during the Clinton administration, they left two unbelievably different rock institutions in their wake. While Wilco spent album after album racing to the brink of experimental chaos before pulling back in the 2000s, Son Volt remained staunchly devoted to the core components of rock 'n' roll storytelling — words, melodies and chord progressions.

Flash forward more than 30 years: The pandemic has given Son Volt’s leader, Jay Farrar, more time to write songs and check out vintage gear. "I had more time to be looking at equipment," the singer/songwriter tells GRAMMY.com. "I came across two amplifiers — one called Electro, the other one Melodier — and I felt like that was emblematic as a title for what I was going for with this record: An emphasis on electric, uptempo, melodic songs."

Farrar couldn't have found two words that better sum up Son Volt's latest, which arrives July 30 via Thirty Tigers. The album is a sequence of well-crafted, warmly-recorded tunes for fans of Tom Petty, the Replacements and Bruce Springsteen. And it's bound to be catnip for those who believe a guitar, a tube amp and a pen comprise the ultimate form of human expression.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Farrar to discuss the road to Electro Melodier, dive into every song on the record and discuss everything from COVID-19 to his 25-year marriage to the civil rights upheaval of 2020.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//IN6Y7YxUlRg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You mentioned in the press release that the title comes from the names of two vintage amplifiers. Is an electric guitar through a cranked-up tube amp all one needs to genuinely express themselves?

It is if you had the background I had, yes. If you had the background I had, all you need is an acoustic guitar and a small amp and an electric guitar. It took me a while to realize what I would call the Keith Richards method of using small amps to record. You know, you get a bigger sound. On the very first Son Volt record, there's a small amp pictured on the cover.

This time around, with the pandemic, I had more time to be looking at equipment. I came across two amplifiers — one called Electro, the other one Melodier — and I felt like that was emblematic as a title for what I was going for with this record — an emphasis on electric, uptempo, melodic songs.

What other gear have you been checking out lately?

On the new recording, I used a baritone acoustic guitar, which is an Alvarez. I've also adapted some new guitars to my live [performance] — when I get back to playing live. I recently had some rotator cuff shoulder surgery from playing too much guitar. Forty years of acoustic guitar took its toll, so like a pitcher in baseball, I got the rotator cuff repair.

I was told to maybe find a thinner-bodied guitar, so I came across an old Kay Speed Demon guitar that I just put some acoustic pickups in and it sounds like an acoustic guitar. So, that's what I'll be going for whenever we start playing live.

Your debut album Trace just celebrated its 30th birthday. What feelings or memories about its making come to mind?

You know, I was living in New Orleans at the time and I had a lot of my equipment in St. Louis. Some of the other guys in the band were in Minneapolis, so I spent a lot of time driving north to south, up and down Highway 61. I used to take the 55 and the 35, just kind of soaking up those parts of the country.

I also remember that I think I hooked up a U-Haul trailer to a Honda Civic — one of the hatchbacks — so I would fit all the equipment in there. Crazy things like that that I wouldn't do now, but I did it. [Chuckles]. I put the expenses for that record on my girlfriend's credit card and away we went.

When you mentioned Highway 61, I remembered that tune ["Afterglow 61"] from Okemah and the Melody of Riot. Is that a place you continually return to in your mind?

Yeah, it runs right along the Mississippi here, near St. Louis, as well as in New Orleans and all the way up from Minneapolis. It's a thread that follows the river and, usually, good music follows the river and the road.

To connect the timeline to Electro Melodier, where would you place this record on the arc of your overall development?

That's a good question. It's hard to put it in context, I guess. Since it was a pandemic record, it was a much more hybrid approach to recording. We started doing this Zoom, remote-type recording on the song "These Are the Times," and sort of realized that some of that synergy and chemistry was lost over recording through a computer in a remote location.

So, some of us got together with masks in the studio and brought that chemistry back. Yet, at the same time, it made sense for Mark Spencer, who's the multi-instrumentalist, to add his parts because he has his own studio in Brooklyn. It was kind of a hybrid approach that I felt worked on this recording. I think the pandemic made the ingredients for this record to sound and be different.

At the very least, remote recording means the bassist and drummer can't look each other in the eye. You lose the pocket.

Yeah, absolutely. There were myriad communication-type problems since everyone had a computer with speakers and you're in different studios with audio monitors. We were just trying to mute the feedback loops from the microphone to the speaker, whether it's a computer, headphones, microphone… It was just too much.

Son Volt. Photo: Auset Sarno

Think we could go track-by-track to see what each song kicks up in your mind?

Sure, we can give it a shot.

Let's start with "Reverie."

I think that song represents what the recording is about: Getting back to basics. It starts with a melody. The song itself is just an exercise with wordplay. There's a baritone electric guitar on that song kind of inspired by Glen Campbell's work on "Wichita Lineman."

What can you tell me about "Arkey Blue"?

There's a bar in Bandera, Texas, which is outside of San Antonio, that I visited once. Its claim to fame was that Hank Williams, Sr. played there and carved his name in a table. So, I had some time off, went there, took a photo of the place. I have a sign in my music room where I play music. So, when I was writing that song, I just sort of used that Arkey Blue bar name as a placeholder title for the song itself.

A lot of lines from that song are directly from a speech Pope Francis gave, talking about turbulent rains never before seen, essentially saying that the pandemic is Earth's way of fighting back. That just sort of blew my mind, the Pope saying that, so that wound up in the song. Ultimately, I just sort of felt like the subject matter in the song has kind of a Noah's Ark vibe, so "Arkey Blue" stuck even though it has meanings that go off in different directions.

Did Hank really carve his name in the table, or was that a rumor?

Ah… well, it's there. It definitely looks the right part. The whole place is straight out of a time warp when you go in there, so it's totally believable that it was Hank, Sr.'s name carved in there. They do have it kind of roped off so people don't mess with it.

How about "The Globe"?

That song, I think, was written through a period of turmoil, both in this country — George Floyd's death protests, Black Lives Matter — and looking at news across the globe. People in Belarus or wherever getting clamped down and their freedoms being curtailed. I think the gist of that song just came out of "We're all in this together across the world." A nod of solidarity to those in this country and across the world.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//uC9XkGQNF5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

And "Diamonds and Cigarettes"?

I guess that one could have been called "Ode to a Long-Term Relationship." The clock just turned 25 years of marriage for me. I think the pandemic also made one realize the people around you are incredibly important. So, that was one takeaway. Laura Cantrell sang backups on that one. I've known her since about 1995. She was interviewing when we were playing the first Son Volt shows back in 1995.

What do you appreciate about her approach to the tune, or just her voice in general?

It kind of blew me away. Again, Mark Spencer, who's the multi-instrumentalist in the band, also plays with Laura Cantrell as her guitar player, occasionally. They had a rapport. I know Laura and her husband, Jeremy, so it was an all-in-the-family type of experience. I felt that she really did a great job.

Where does "Lucky Ones" fit into the puzzle?

There were always cross-currents of R&B, soul and country music that I've always liked, whether it was Dan Penn, Charlie Rich or the Flying Burrito Brothers. That was my take, or my attempt at tapping into that aesthetic via rhythm and blues and country soul.

I remember the old cover of the Burritos' "Sin City," so obviously, that DNA runs deep.

[Shyly] Yeah, yeah. For sure.

And "War on Misery"?

A couple of years ago, some kids in town in St. Louis had put a manifesto in my mailbox called "War on Misery." It was kind of a self-published socialist manifesto. I could concur. I could relate. So, that title kind of stuck with me. I was trying to go with a Lightnin' Hopkins type sound. Lightnin' Hopkins would often perform with a regular guitar tuned way down, so he had this deep, baritone sound.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//lZOJjos7G-0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

How about "Livin' in the USA"?

It didn't start out as an intentional thing, but in retrospect, I see it as a nod to songs like Bruce Springsteen's "Born in the USA" or Neil Young's "Rockin' in the Free World." Both of those songs have a similar thematic thing going on. I feel like those songs establish a thematic tradition, so I was just kind of taking it and running with it.

But yeah, again, a lot of turmoil going on and looking around and seeing things that don't add up and putting them into the song.

Both songs are antimatter national anthems. Widely misunderstood, too.

Yeah, exactly. There could be some of that that happens with this one as well.

How about "Someday is Now"?

We started to veer off into prog-rock land a bit with that one, but we consciously kept in check. There were a few times in the recording when we had to pull it back from sounding too much like Rush but I think it ultimately sounded more like Zeppelin.

Has prog always been part of your creative stew?

Not so much for me, but it's in there somewhere, I suppose. Once it gets in there, you can't shake it out completely.

Tell me about "Sweet Refrain."

There are some COVID-19 references, I think, in there. "Looking out the window panes" — I spent a lot of time doing that in the last year and a half. Again, there's some references to relationships and that kind of thing, but there's also a line in there: "Another hero is gone," which references people that passed during COVID, like John Prine.

That song is also an example of a stream-of-consciousness type, where it kind of goes from one verse to the next and jumps around. The final verse references some of the folks in Benton, Mississippi — [Jimmy] "Duck" Holmes and Skip James. I've used that tuning before and I felt like I wanted to tip a hat to that tuning.

And how about "The Levee On Down"? That symbolism weighs heavy in blues and country.

Yeah. I live close to the Mississippi River, so I've driven up and down the levees. They usually have roads on them. You can drive up and down. I was going to make a bad joke about a Chevy on the levee, but I'm not going to do that.

I'm going to say that from driving up and down Highway 61 into Cape Girardeau, Missouri, when you go about an hour and a half south of St. Louis, there's the Trail of Tears crossing where the Cherokee Indians crossed. Many died on their way to Oklahoma due to the Trail of Tears forced march, and the person that was part of that was Andrew Jackson. He's on the $20 bill.

Then, we've got "These Are the Times."

That was very much a COVID reference. Changing times, and this is where we're at. Let's try to find our way through this.

We're almost through with the record. "Rebetika."

I came across that word in reference to a certain kind of Greek folk music that was described as being close to blues. It had maybe a similar impetus as blues. I just found that to be kind of fascinating. I took the title "Rebetika" and just kind of ran with it.

Then, after "The Globe / Prelude," we close out with "Like You."

Yeah, that was a stripped-down version—almost like a demo—of "The Globe." We were recording that very much in the [midst of the pandemic]; I think it was when the Black Lives Matter protests were going on. We actually released, I think, on Bandcamp during that time frame.

<iframe style="border: 0; width: 100%; height: 120px;" src="https://bandcamp.com/EmbeddedPlayer/track=1288164418/size=large/bgcol=ffffff/linkcol=0687f5/tracklist=false/artwork=small/transparent=true/" seamless><a href="https://sonvolt.bandcamp.com/track/the-globe">The Globe by Son Volt</a></iframe>

I always tend to forget about the very last song, but then it sticks in my mind. I guess the way I would summarize this whole project is that I had more time to work on the song structures and arrangements — the writing itself — and more time spent recording the vocals. Really, all of it.

It spanned the course months where often, in the past, the recording would happen between the gigs. With that song, Jacob Detering, who did the engineering, played a sort of drone, a Mellotron-type instrument on that. More time, more team. I think those were elements that went into the making of this record.

Photo: Robby Klein

interview

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

On his third album, the self-described "black sheep" of country music proves he's here to stay.

Haters take note: nothing fires up a country boy like HARDY more than a naysayer. And this redneck has a long memory.

Despite the coveted catalog of country music hits to his credit — tunes he wrote for artists like Florida Georgia Line, Blake Shelton and Morgan Wallen, plus his own work as a solo artist — HARDY's third album begins with a three-minute response to a heckler who once left a nasty note in his jar in place of a tip.

That moment may have occurred a decade ago, but it's key to HARDY's defiant persona. In fact, the album's title is exactly what that note read — Quit!! — and its cover art is the actual napkin the message was written on, which the singer/songwriter has held on to all these years.

HARDY laughs off the memory at first, but as the title track plays on, his olive branch soon turns to coal. "I'm not the GOAT, I'm the black sheep hell-bent to find closure," he barks as the song escalates. "I can't let go — a note somebody wrote like ten years ago put a chip on my shoulder. If you wanted me to quit, you should've saved it, bro."

The takeaway here? HARDY won't quit. Or, to quote another Quit!! banger, "I DON'T MISS," when a hit is in the crosshairs, he "don't hit nothing but the bull's eye."

No doubt, he has the numbers to back it up. HARDY linked up with Florida Georgia Line after moving to Nashville in the 2010s, and landed his first country No. 1 as a songwriter in 2018 thanks to the duo and Wallen, with the smash "Up Down." As he began building a solo career — releasing a pair of EPs in 2018 (This Ole Boy) and 2019 (Where to Find Me) — he continued delivering chart-topping hits for FGL, Shelton, LOCASH, Wallen, Dierks Bentley, and more. As Quit!! arrives, HARDY boasts 15 No. 1 hits: 11 as a songwriter, and four as an artist.

Along the way, HARDY also established his Hixtape series, a countrified version of a hip-hop mixtape now three volumes deep, bringing together friends and superstars like Keith Urban, Trace Adkins, Thomas Rhett and a host of other stars to collaborate. Not only did Hixtape Vol. 1 land HARDY his first No. 1 as an artist in his own right — the Lauren Alaina and Devin Dawson team-up "ONE BEER" — but it put HARDY's shapeshifting musicality front and center.

"A lot of people ask, 'When did you decide to jump into the rock and roll thing?' HARDY, who uses his last name as his stage name, says. "I feel like I've always dipped my toes in it here and there, and a lot of my songs have been really close to it but not quite there. Hixtape, especially Vol. 1, I was definitely foreshadowing my sound, and I really didn't even know it at the time."

By now, modern country musicians regularly reflect influences from beyond Nashville's confines. But HARDY has played a big role in rock's country crossover, as he gradually showed more of his Mississippi-bred, guitar-riffing roots on his 2020 debut album, A ROCK. He fully embraced them on the 2023 double album, the mockingbird & THE CROW; while the first half has more country-oriented tunes like the Lainey Wilson-featuring murder ballad "wait in the truck," he lets loose on THE CROW.

"THE CROW will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am," he asserts. "It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record."

HARDY has not only been an architect of this genre blending, but also its chief proponent — so much that in 2023, the L.A. Times crowned him "Nashville's nu-metal king." On Quit!!, he cashes in that currency with the gargantuan guitar riffs and bombastic beats popularized by acts like Limp Bizkit, and leans deeper into the rhythms and playful lyricism of hip-hop, a skill he recently flexed at the request of Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre on a hicked-up rendition of Snoop Dogg's G-funk classic "Gin and Juice."

Ironically, the further HARDY gets from straightforward country music, the closer he gets to who he really is as an artist. Below, the chart-topping star details the backstory of Quit!!, his conflicted relationship with the country-music formula, and how he'll continue pushing boundaries within the genre and beyond.

You grew up in the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. What role did music play in your upbringing?

My dad introduced me to rock and roll in general, but it was his era of rock and roll. Whatever you define as classic rock and everything under that umbrella. But music was a big deal in Philadelphia and it still is. There were tons of cover bands, and a lot of [my] buddies were into music. So that had a big influence on me.

I, thankfully, was in that last era of kids that the only time they got to hear a song was on MTV or on the radio. And I remember hearing "In the End" [by] Linkin Park, and then getting Hybrid Theory on CD. I remember the first time I saw [Limp Bizkit's] "Nookie" video on MTV. I was heavily influenced by all that stuff. I'm very thankful that I grew up in the era before the internet was really big.

Were you into country music back then?

Surprisingly, not at all. Not until Eric Church, Brad Paisley, a couple of people started singing about stuff that really piqued my interest. But no, I didn't really listen to much country.

I think the only country that I listened to, if you even call it that, was Charlie Daniels. He played at the Neshoba County Fair. I got to see him twice. But even he was more of, like, you'd almost call it more Southern rock. For some reason, country music at the time didn't do it for me. It took me a long time to get into it.

You recently re-envisioned "Gin and Juice." Were Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre big artists for you when you were younger?

Yeah, especially Snoop. Snoop was in his later years when he started doing more pop stuff. I was a little too young for Doggystyle. I was 4 years old when Doggystyle came out, so my folks weren't letting me listen to that. But I will say, [Dr. Dre's 1992 album] The Chronic and especially [1999's] Chronic II, those records were huge. And anything that Dre touched after that, like all the beats he produced for 50 Cent, and obviously I'm a huge Eminem fan. I mean, all the way up to Kendrick [Lamar]'s early stuff.

I don't know how much they influenced me musically, but I definitely listened to both of them at the time.

You've got so many projects and co-writes and stuff going on, always. Is it easy to pinpoint where your journey to Quit!! began?

I can tell you for a stone-cold fact that "BOOTS" [from A ROCK] is responsible for the album Quit!! That was the first song that I ever wrote that had a breakdown in it. And when I played that live before it came out, people didn't know it, so it was a little different then. But once the song came out, and we started playing it live, it was bigger than "ONE BEER." It was bigger than "REDNECKER." It was the biggest song in our set, and to this day, it's still one of the biggest songs in the set.

But because I love the rock and roll sound so much, that's the song that I was like, Okay, this is working, because these people are losing their s— when we go into this song. So, then, that inspired me to write "SOLD OUT," and once "SOLD OUT" came out, and we started playing that song, that song was even bigger than "BOOTS," and it was heavier than "BOOTS." After "SOLD OUT," it was "JACK," and it's just a snowball of writing heavier songs and having the courage to keep going. "BOOTS" crawled so that Quit!! could run, you know? That was definitely the song that started it all.

The new album builds on the mockingbird & THE CROW and the direction you were heading.

Yeah, I think it builds on it maybe in the sense that there's a lot more screams, and maybe more breakdowns, and it's a little heavier than the mockingbird & THE CROW at times. But it is also very different. There's a lot more, like, pop-punk stuff and, I don't even know what you would call it, post-hardcore-sounding s—.

But all of the rock and roll stuff stands on the shoulders of THE CROW. It will always be that cornerstone moment that defined who I am. I mean, it definitely teed me up. It gave me the courage to do this Quit!! record.

I like that word, courage. It's not a word I expected to hear out of you based on your persona, but that's a very interesting way to phrase it.

No, I mean, the metal and country cultures are very, very, very different. There's never fear, but there's definitely, what's the right way to say that? You know, there's like when we throw like the goat horns and s— on the screen. Country has a big Christian background, and metal is like the exact opposite of that, and those can clash a lot, but there's definitely a little bit of some reserve — it seems to not get too much push back — mixing the two. My mom's not crazy about it, but what can you do?

And you have moments like "wait in the truck," where you're not writing for the party. Do you see yourself pursuing those avenues more often? Does the world want to hear HARDY reflect?

You mean like more of the deeper country stuff?

Correct, yeah.

I hope. That's the s— I love. I feel like they're so few and far between. Like, "wait in the truck," we just got so lucky. I feel like "ONE BEER" was kind of the same. Like, it's gotta be the right day, and the right time, and the right people in the room to really tell a story. It's tough. But I would love to continue to have those cool story songs.

But what I will say is there's a lot of gray area between the black-and-white of HARDY country and HARDY rock and roll. I'm still going to put out country songs. The gray area is that to me and to a lot of people, they're all just HARDY songs. But I have so many songs that I have written that I wanna put out that are so, maybe if they're not storylines, they're even deeper down the rabbit hole of thought-provoking stuff, like "A ROCK," or maybe even "wait in the truck," or even a song I have called "happy," on the last record — just songs that are very, very thought-provoking.

Just trying to push my own boundaries of country music, and not everything is right down the gut, you know, "let's go to radio with it." But just really trying to experiment with what I wanna say with country music. So, yes, there's definitely more of that coming.

You're playing your first headlining stadium gig in September. How has performing in those venues, and anticipating that, informed how you write? Are you writing for the stage?

Yeah, 100 percent. I would say, 75 percent of the time you're writing for the stage — even if it's not for myself, if I'm writing for somebody else — I'm definitely writing for the stage. I cannot tell you how many times I've sat in the room and been like, This s— is going to pop off live! And then try to put the other writers in that headspace.

Like on [Quit!! track] "JIM BOB," when we did the pow-pow-pow! thing, I'm like, just think about how cool it's gonna be live, and living in that headspace, because that's where it all comes to life. That's the end product.

Writing for the stage is something that a lot of people do. And that's why songwriters love going out on the road, is because they go out and they write songs with these artists, but they love watching the show because they get to see what really translates live, and then take that back to the writing room and try to recreate that.

Did that kind of experience have anything to do with you making the move to a marquee artist? Because not all songwriters can make that jump. Or was that always the plan?

Yeah, I mean, it was always that kind of thing. I was fortunate that I got to see Morgan [Wallen] perform "Up Down," and FGL perform a couple of their songs before I made the jump into an artist. I kind of already scratched that itch a little bit.

The Nashville writing scene can seem like a 9-to-5 kind of boring thing. But it doesn't sound that way from the way you describe it.

It's a little bit of both. The funny thing about that is like, if you walk into a publishing company, 10:30, 11 o'clock, whenever people start getting there, it's a bunch of dudes or girls standing around drinking coffee, hanging out. It's like a break room, and then everybody's like, "All right, well, y'all get a good one." And then everybody goes into their own rooms. That part of it is very 9 to 5.

But there is definitely — especially with our group of people, when you get on something that is so special, it's beyond, like, "We're writing a hit today." There's just something that transcends that. I don't know how to describe it, man. That's when it's really, really, really, really great. The Nashville process, that's what it's all about — having those moments in the room where you're like, "This is special," and, like, "We're witnessing something special that is going to affect people on a global or on a nationwide scale."

I remember when we wrote "wait In the truck" and how we were all just gassing each other up because we were like, "Dude, this song is gonna help a lot of people." And that's when the 9 to 5 goes away. We're being creative together, and it's a special thing.

There's been so many moments like that, where you're just so thankful to be a part of a great song, and how hyped everybody is. It's a feeling that's really, really hard to beat.

More Of The Latest Country News & Music

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Koe Wetzel On How New Album '9 Lives' Helped Him Tap Into His Feelings

Katelyn Tarver's "Everyday Is A Winding Road"

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

Amy Grant Shares Where She Keeps Her GRAMMYs

Photo: Rich Fury

list

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Not a Phish phan? No worries. Ahead of their 26-date tour and new album, 'Evolve,' dig into this primer on the music and the subculture of the most popular jam band since the Grateful Dead.

Mainstream rock or pop, Phish are not. While the foursome from Vermont are definitely a jam band, that label does not capture their unique sound and varied influences. Both on record and live, Phish's extended improvisations noodle from reggae and all forms of rock, to bluegrass and funk, with healthy doses of country, blues and jazz.

Like the jam band godfathers the Grateful Dead, Phish built its devoted fanbase not through singles and airplay, but via tireless touring and word of mouth. On some nights — okay most nights — even the band has no clue where their rambling live shows will go. This spontaneity has been Phish's guiding ideology from its earliest days playing college campuses to their annual residency at Madison Square Garden; there is nothing contrived or calculated about a Phish show; instead, the band's filled with surprises and set lists that change more frequently than you change your bedsheets.

For more than 35 years now these four souls have been taking Phish-heads along on this joyous musical ride to unknown soundscapes. Concerts are fueled by passion, not perfection. Ask 10 Phish phans what their favorite live show is from the band’s history and likely each will offer a different answer and argue the reasons for their choice as if it were a thesis defense.

Read more: A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

For Phish, it’s not about awards and accolades. The group has just one GRAMMY nomination and its highest charting single came and record came 30 years ago. In 1994, Billy Breathes peaked at No. 7 on the Billboard 200; its lead single "Free" hit No. 24 on the Billboard Hot Modern Rock charts and No. 11 on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart.

What attracts people to Phish's music and subculture is the mood, the groove and the community; that’s why the band perennially have been one of the highest grossing live acts throughout their career. The band is also part of American pop culture: They have a Ben & Jerry’s flavor (Phish food), have appeared on "The Simpsons" and been parodied on "South Park."

This spring, Phish became only the second band (after U2) to perform at the Sphere in Las Vegas. Over the weekend of April 20, the foursome played four shows with a completely different set each night. The final show on Sunday evening featured an epic second set, even by Phish standards: the band performed for nearly two hours and jammed on for 34-minutes on "Down with Disease."

Surprises like this musical meandering abound at Phish shows and it’s another reason fans shell out a hefty chunk of their pay cheques to see them live again and again and again; it’s also what makes attending one of their concerts a unique experience. The relationship between the band and these devotees is symbiotic. Both inspire and guide the other.

Phish does not take itself too seriously. This is reflected in their songs, their artistic approach and their love of a good prank. Ready to go Phishing? Not the dictionary adjective that conjures negative connotations of scams and identity theft, but rather, a new word we suggest adding to the Urban Dictionary meaning to take a deep dive into the weird and wonderful world of Phish.

In advance of the band’s 26-date tour that starts with a three-night run in Mansfield, Massachusetts to promote Evolve — its 16th studio record that arrives July 12 — GRAMMY.com offers a lowdown on these musical merrymakers. Read on for a guide to appreciating and approaching Phish's lingo, lore, and lengthy discography.

Phish 101

Before the band had a name, a following, or conferences and university courses dedicated to the study of their music, they were just a bunch of college kids jamming in their dorm. The original members of the band met while attending the University of Vermont in Burlington. Initially formed as a trio in 1983 that featured guitarists Trey Anastasio and Jeff Holdsworth, along with drummer Jon Fishman. Bassist Mike Gordon joined that fall. In 1985, keyboardist Page McConnell was added and Holdsworth left. Today, it's these four (Anastasio, Gordon, Fishman and McConnell) that comprise Phish.

Junta, the band’s self-released debut arrived on cassette in 1989, followed by Lawn Boy the next year on Absolute A Go Go Records. The industry buzz created by their live shows then led to a multi-album deal with Elektra Records, who, in 1992, released their major label debut A Picture of Nectar, along with reissues of Junta and Lawn Boy.

What’s with the name? Everyone loves a good band name origin story, and there are often several versions of Phish's. The simplest and most popular one cited is that Fishman was asked at an early gig for the band’s name and thought they were asking for his name, so replied with his college nickname, "Fish." It stuck and they just changed the spelling.

A Lesson In Lingo: 4 Phish Phrases

Next up on the Phish syllabus is a lingo lesson in lingo. Overhear a pair of Phish fanatics chatting in a coffee shop, and you’ll wonder if they are speaking a different language. These devotees have developed their own lingo to express their love for all things Phish. Here’s a quick primer to help you converse with phans as if you know what you are talking about.

First, phans label each era of the band a number and these labels describe when their love of Phish began: 1.0 refers to the band’s beginnings until its first break in 2000; 2.0 is a short period and a small cohort of fans that starts when Phish returned from its first hiatus in 2002 and ends before they officially broke up in 2004. Finally, 3.0 refers to new converts: fans who discovered the band only after they reunited for good in 2009.

As this schooling on Phish continues, here are four words to drop into a conversation with a Phish fan to make you sound educated. "Noob" is a condescending word referring to a newbie, like post-2009 phans. A "chomper" is someone who talks during songs at a Phish concert (definitely a no-no). "Spunion" is someone whose appearance, actions and speech indicate they’ve taken way too many drugs. Finally, "hose" is a free-flowing improvisational jam where the music feels like it just flows directly into the listener’s ears.

Down On The Farm: Hits & A Few Phan Favorites

From the 2000 record of the same name, "Farmhouse" is one of the few Phish songs that made a splash beyond just their fans thanks to this radio-friendly chorus: "I never ever saw the Northern lights/I never really heard of cluster flies/ I never ever saw the stars so bright/ In the farmhouse, things will be alright." Besides this earworm, the ninth record from the band also featured another one of its biggest charting radio hits: "Heavy Things," which reached No. 29 on Billboard’s Adult Top 40 chart and No. 2 on the Adult Alternative Songs charts.

Some other key studio tracks to explore and listen to that show the depth and breadth of the band’s talents include: "Golgi Apparatus," "Chalkdust," "Torture," "Sample in a Jar," "Character Zero" and "Sand."

Into The Studio: A Choice Phish Records

Phish have released 20 studio albums and 53 live records. That’s a lot of music to sift through for any newbie. Three key albums to help understand and get into the band include: A Picture of Nectar (their major-label debut from 1992 that was certified gold), Hoist (1994) and The Story of the Ghost (1998), recorded at famed Bearsville Studios in in Woodstock, NY - a record Trey Anastasio described as "cow-funk." Listen carefully to this trio of records and you’ll come away from these deep dives either loving the band and ready to take the next step on this phishing trip or not.

Make sure to also check out the conceptual album Rift. This follow-up to their major-label debut is a fan favorite and also a critical darling. It’s possibly the band’s greatest studio creation, but it’s also an acquired taste. Rift follows the story of a man who dreams about the rift in his relationship with his girlfriend. The listener follows this protagonist on a dark and heavy ride as his emotional journey turns from a pleasant dream to a nightmare. The narrative is told backed by a sonic palette that showcases all of Phish’ colors and musical influences: from jazz and blues to psychedelic rock and funk.

Go See Phish Live

As Neil Young sang in "Union Man," that is often-quoted by concert lovers, "live music is better bumper stickers should be issued." Phish subscribe to this mantra and are known to plaster their cars in bumper stickers. The centerpiece of a Phish show is extended jams and the communion between Phish fans, but their concerts also feature amazing light shows, props, and pranks.

To get a sense of what attending a Phish concert is like, start with the six-disc set Hampton Comes Alive. Released Nov. 23, 1999, the collection consists of two concerts in their entirety captured at the Hampton Coliseum in Hampton, Virginia in 1998. The title plays on Frampton Comes Alive! — one of the best-selling live albums of all time.

In the band’s early days before the Internet came of age, bootleg tapes abounded. Trading these — just like Grateful Dead fans do — was always a part of Phish culture. LivePhish captured all of the band’s live shows. This is now an Android app where you can stream shows, past and present. Mere minutes after each Phish concert ends, the newest show is uploaded.

Before the streaming age, the band frequently released CDs up to six discs in length (most Phish concerts run more than three hours). One of these essential listening live releases is Darien Lake from Sept. 14, 2000 that includes a cover of Neil Young’s "Albuquerque."

Order Up The Baker’s Dozen

For Phish fans, the 13 concerts dubbed The Baker’s Dozen are pure bliss. The residency occurred at the Manhattan mecca from July 21 to Aug. 6, 2017. Every night featured a different set list (26 total sets as they played two each night). No song was repeated and each night had a theme.

Over the course of 13 shows, Phish played 237 songs. A highlight of The Baker’s Dozen was a 30-minute jam of "Lawn Boy" — a song that usually clocks in under four minutes.

Cover Me

Many consider the group the greatest cover band on earth, so go down the Phish YouTube rabbit hole and what matters at this moment in your life is sure to get neglected for a while.

An understanding of Phish's many collaborations and covers tis also essential to better appreciate the band. Phish has paid homage to everyone from classic rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd, ZZ Top, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, to Frank Zappa and the Talking Heads. Collabs include: Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, and weird as it sounds, even Jay-Z, who the band invited on stage during a Brooklyn gig in 2004, to sing-along on the 24-time GRAMMY-winner’s hits: "99 Problems" and "Big Pimpin.’"

Trick Or Treat Tributes & Auld Lang Syne Shenanigans

Halloween shows always feature musical costumes where Phish plays another artist’s album from front to back. The Beatles' White Album in 1994 is especially good and the first time the band premiered this concept. Many fans claim the 1998 Halloween show where the band covered the Velvet Underground’s Loaded is one of the most underrated and was mind blowing. But the best might be from 2018 when they invented a fake Scandinavian synth-rock outfit called Kasvot Växt.

For years, Phish have celebrated another year come and gone along with their fans, often playing a string of shows leading up to New Year’s Eve. Pranks are always a part of these special occasion gigs and there's often a theme with stages being transformed to transport their phlock to other realms.

Many of Phish’ most legendary end-of-year celebratory concerts occurred in New York City at Madison Square Garden where they’ve performed to close out the year 15 times. One of the most memorable saw the band "send in the clones" on Dec. 31, 2019, to ring in another new year.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Photo: Danielle Ernst

interview

Mexican Rockers The Warning On 'Keep Me Fed' & "The Possibility That We Could Literally Do Everything"

The three sisters of the whiplashing Mexican rock band The Warning sat down with GRAMMY.com to talk about their biggest recorded leap to date, 'Keep Me Fed.'

The Warning have been around for over a decade, with three previous albums under their belt — but they've never hit with gale force quite like their single "S!CK." Get a load of them on a recent "Kimmel" performance below; when singer/guitarist Daniela "Dany" Villarreal Vélez screams the title, her bandmates — her sisters, bassist Alejandra "Ale" Villarreal and drummer Paulina "Pau" Villarreal — respond with a groovy, steamrolling riff.

From harmonies to songwriting to sheer charisma, The Warning have reached a new pinnacle with their fourth album, Keep Me Fed, which arrived June 28. It's packed with bangers: the boiling-over "Apologize," the chugging, Spanish-language "Qué Más Quieres," and pop-laced detours that stick, like "Hell You Call a Dream."

The Monterrey, Mexico trio have opened for some of rock's titans over the past few years: Guns N' Roses, Foo Fighters, and Muse. This only incentivized them to make Keep Me Fed hit as hard as humanly possible.

This involved reaching out to rock's blue-chip writers, like Dan Lancaster and Mike Elizondo, to help the songs truly hit the jackpot. But speaking to the three on a four-way call, it's clear their success really relies on their sisterly synergy: they effortlessly bounce off each other in conversation, just like they do in the studio or on a stage.

Read on for a full interview with The Warning about the road to Keep Me Fed, songwriting in Spanish and English, and how supporting the greats spurred them to make a swing that connected.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

**Bring us from the Error era to Keep Me Fed. What transpired in The Warning's history?**

Pau: We grew so much as people, through our experiences touring with Foo Fighters, Muse and Guns N' Roses. You can't help but learn and grow from all of these experiences and shows.

We were very inspired, and I feel like Keep Me Fed was the first opportunity we had to sit down and actually process everything that we had been through, and just put it directly into the music.

Ale: We were recording and writing in between tours; we had a hectic schedule. I feel like you can definitely hear that chaotic energy, and everything we lived through this past year while writing the album.

You opened for some of the biggest rock bands on the planet. Tell me more about how that fed into the music.

Pau: Seeing these amazing musicians playing every night, you can't help but want to push yourself. What made us grow was that hunger to be better. We wanted to be a good opener for these legendary bands. We wanted the crowd to be impressed; we wanted to prove ourselves to these new crowds.

And, not only with our live performances: we knew we were going to write this album, and release new music. And if these new people were going to look for our new music, we wanted it to be this insanely huge step forward in our careers.

Musically, our biggest references are Muse and Royal Blood — and we toured with them. So, by seeing what they do live, and how their ideas are [executed], we had a really good idea of how we wanted our ideas to sound live.

Dany: Coming home from the tours to process everything that you went through, I think unconsciously you let everything out, and let everything go when you're writing music. I think that played a big part in what we came back to express in the Keep Me Fed songs.

Can you talk about working with outside writers on Keep Me Fed?

Ale: We've always only worked within the few of us, so adding someone else to the mix was very different. It's so interesting to see how other people work, and working with them, and hearing all of these different ideas. I feel like we learned so much from every person we wrote with.

Dany: We have three songs with Dan Lancaster, who is touring with Muse now; he's a great producer as well. We worked alongside our producer, Anton DeLost, for the whole record. They are such a dream team, honestly. They knew how to push us toward a direction that made us get the best out of us.

We were so surprised by the stuff we lived through — very intense, specific feelings, that they can relate to in a totally different way. We managed to connect the dots between feelings and what we wanted to express.

Pau: Also, they're not necessarily rock writers. Some of them are pop. Some of them are R&B writers. It's a really big melting pot of styles and inspirations and experiences.

You start learning little tricks and tips from each person. So now, even when we're writing alone, we channel everything that we learned from these individual writing sessions.

And I feel like we look at songwriting in a new way — especially because we are Mexican, and English is not our first language. So, we write in English with a very different mindset; we think in Spanish while we are writing in English. We see language in a more phonetic way.

So, finding new ways to look at the language that we write in, and new ways to communicate what we want to say through the words or eyes of these other writers, was a very enlightening experience.

The Warning - Qué Más Quieres (Official Video)

Keep Me Fed sounds absolutely massive. How did you craft that sound?

Dany: We were very focused on making it sound as big as possible, and as close to our live performance energy as we could. Guitar-wise, we explored a lot of different fuzz pedals, which was very new to me. I wasn't very much of a fuzz girl, but oh my god, it adds so much texture, and it added to the sound that we wanted to hear.

Also, we went a lot heavier with this album. I experimented with playing with baritone guitars, so I could be a lot lower than I usually am. I love that; it makes me feel so powerful, and I think it adds a lot to the songs.

Ale: I recorded all my bass parts with a pick, which is something I don't do; I only play with my fingers. But for the recording, it sounded clearer, and made the bass stand out, as we're only a three-piece. So, I liked exploring that.

Dany: I learned to play with a slide. I had never done that before. And I had to figure out how to play it live down the road. It really pushed us, and me, to stay sharp and do what was necessary for what we wanted to express in the music.

Vocally, I experimented with a lot of different textures. We usually just go all out and do this angry screaming that I know how to do from our 10-year career. But this time, I [explored] the dynamics more and more. I went soft, I went a little more airy, and then I screamed. It was fun to get to know myself more as a singer and guitar player.

Pau: We explored a lot of different styles. You can hear different [unexpected] influences. "Burnout" is really funky and groove-driven. "Apologize" is just a very angry song. "Sharks" is this type of new thing. It's just so varied.

We let ourselves be open to the possibility that we could literally do everything. We could try everything out, and it would still fit in this album, because it was still us.

Explore The World Of Rock

HARDY On New Album 'Quit!!' & How "Trying To Push My Own Boundaries" Has Paid Off

A Beginner’s Guide To Phish: 8 Ways To Get Into The Popular Jam Band

Mexican Rockers The Warning On 'Keep Me Fed' & "The Possibility That We Could Literally Do Everything"

Watch Red Hot Chili Peppers Win Best Rock Album

Darius Rucker Shares Stories Behind 'Cracked Rear View' Hits & Why He's Still Reveling In "A Dream Come True"

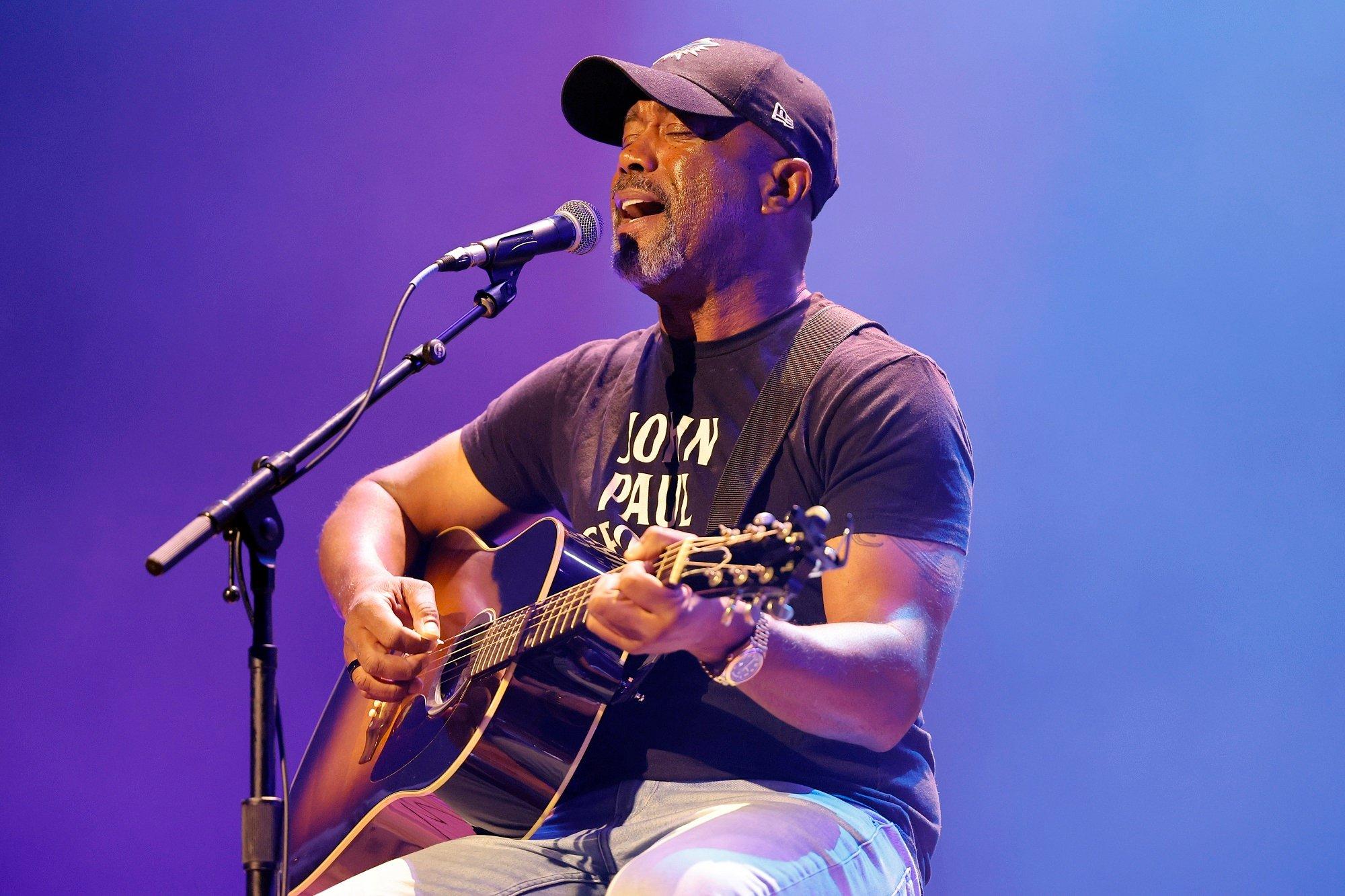

Photo: Jason Kempin/Getty Images

interview

Darius Rucker Shares Stories Behind 'Cracked Rear View' Hits & Why He's Still Reveling In "A Dream Come True"

Thirty years after Hootie & the Blowfish's seminal debut — and nearly 20 since he forayed into country music — Darius Rucker looks back on some of his fondest memories that he further explores in a new memoir, 'Life's Too Short.'

July 5, 1994 was the day Darius Rucker's life forever changed.

That was when his band, Hootie and the Blowfish, released their seminal debut, Cracked Rear View. Within a matter of months, the album went on to launch his band into the mainstream stratosphere. By mid-1995, Cracked Rear View topped the Billboard 200 — where it stayed for eight weeks — and by February 1996, the band went two-for-two at the 38th GRAMMY Awards, where they were awarded Best New Artist. Three decades on, Cracked Rear View remains one of the best-selling albums in U.S. history.

For Rucker, who has also enjoyed a successful run as a solo country act since 2008, it's all part of a triumphant journey that he recalls in his new memoir, Life's Too Short. A candid retelling of his eventful life, the book recounts the high-highs of musical dreams gloriously come true and the love of his family — including his late mother Carolyn, a frequent inspiration, particularly on his latest set, 2023's Carolyn's Boy. Rucker is also frank about his run-ins with the struggles of his massive success, including the scourge of racism he encountered along the way.

In celebration of Cracked Rear View's big anniversary and the recent release of Life's Too Short, Rucker spoke to GRAMMY.com about his band's biggest hits and career-making success, as well as the moments he knew Hootie, and his country venture, were about to be big.

How would you say Hootie's sound came about? Was it a natural evolution, or did you have a very clear sound in your head?

It was definitely natural. It all started with Mark and I in the USC dorms, realizing how much of the same music we knew and [were] jamming together — R.E.M., the Eagles, the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Hank Williams, Jr. and KISS. We both grew up on a huge variety of music, and all of those influences shaped our own songs once we started performing and writing together.

There was a brief moment where we tried to do some heavier stuff as grunge was getting popular, but that wasn't us. Hootie was always going to sound like Hootie.

Congratulations on the the 30th anniversary of 'Cracked Rear View.' When you think about that time in your life and the album, I'm sure the memories just come flooding right back?

Oh, so many. You know, we'd been writing songs for so long and playing them at our live shows, doing everything independently and having pretty good success with it. But making this one was different, because we had a real record deal finally, after so many "almost" deals falling apart, and we went out to a studio in L.A. to record the album. We had Don Gehman there producing, and I just remember feeling so much joy being in that room making music together.

Does any one story stand out?

One of my favorites, and I talk about this in the book, is David Crosby coming to sing harmonies on "Hold My Hand." We were trying to figure out who would do it, and our friend Gena Rankin threw out David's name. She said it so casually, we all thought she was messing with us. There was no way a legend like him was going to come be part of this project! Sure enough, two days later he walked into the studio [to record it]. I still can't believe that happened.

Looking back, the album launched a variety of iconic singles. For example, I know "Hold My Hand" is a special one for you.

Jim "Soni" Sonefeld actually brought "Hold My Hand" to us when we were holding auditions for a drummer. He finished playing and told us he heard we were starting to write original music, so he popped a cassette in with this song on it. We obviously canceled the rest of the auditions.

What about a song like "Let Her Cry"?

I was sitting at a bar in Columbia [South Carolina] when I heard The Black Crowes sing "She Talks to Angels" for the first time. I was transfixed. I made them play it again and again until they wouldn't anymore, and then I went to every bar on the street and made them all play it.

When I finally went home, I tried to shake the song off by listening to something else great, so I put on Bonnie Raitt's Home Plate CD, and eventually decided I was going to write my own "She Talks to Angels," for Bonnie Raitt. The next morning I told Dean [Felber, the band's bassist], who I was living with at the time, that I had drunkenly recorded a song on our little four-track last night and we should listen to it because it was probably pretty funny. It wasn't funny, but it was pretty good.

"Only Wanna Be With You" was another one of the album's many hits. Where did that song come from? I'm especially wondering about one line in there: "I'm such a baby 'cause the Dolphins make me cry."

Anyone who knows my story knows that my mom, Carolyn, had a huge impact on my life and still does to this day, even though we lost her a long time ago. But she also had a specific impact on this song.

I had started writing it, with the chorus and some pretty good lyrics down, but I wanted to add more personal details and couldn't really get it right. I had taken a break from writing to watch the Dolphins game, and as they were about to lose once again after blowing a lead, my mom called. She heard me sniffling, and even though I blamed allergies, she immediately knew it was because of the game. "Unbelievable. Are those Dolphins making you cry again?!" The rest is history.

When did you realize 'Cracked Rear View' was something special?

Our fourth single "Time" really pushed us over the edge in dominating radio airwaves in a way that was hard to wrap our heads around, and really still is. I remember being in a car one time, and "Hold My Hand" was playing as soon as we turned on the radio, which was funny — but honestly, pretty expected at that point. We hit seek through the next few stations and — you can't make this up — "Only Wanna Be With You," "Let Her Cry" and, yep, "Time." Four stations, four Hootie songs. It was wild.

How did your life change?

Oh, it was a rocket ship. I always tell this story, but David Letterman heard our song on a Tuesday, put us on his show on a Friday, and by Monday, we were the biggest band in the world. It happened that quickly, and the opportunities that came from that changed our lives.

Aside from the big hits, were there any songs on the album that particularly meant something to you?

"Drowning" was an important song for me because I wrote it during the early days when we first started transitioning from covers to our own music, and I wanted to get deeply personal in what I put in songs. I put the hurt I felt from all of the racism surrounding us in that song. The lyrics literally ask, "Why is there a rebel flag hanging from the statehouse walls?"

The band supported me with that song, just like they did at shows where people casually threw the N-word at the stage. Like it has been my whole life, music was my outlet for dealing with that hurt. And I resolved that such ignorance would never stop me.

From 'Cracked Rear View' to 'Carolyn's Boy,' your songwriting as a whole has gotten much more personal. Why has that changed?

I actually think Cracked Rear View was pretty personal. The example of "Drowning" I mentioned earlier kind of shows that. But the vibe of Hootie was so happy-go-lucky that sometimes the deeper meaning of the lyrics got missed.

Country music is all about the lyrics and the storytelling, though, so I think that shows through in my newer music in a more prominent way. And with Carolyn's Boy specifically, I experienced a lot of life during the time we were writing that album. From the pandemic, to relationships, to my kids getting older and leaving the house, there was a lot of life to process and I put all of that into song.

Lightning struck twice when you branched out as a solo act and embarked into country music. When did you realize you made the correct gamble?

It was on Oct. 3, 2008. I had always wanted to make a country record, just because I love country music. When I came to Nashville, I wasn't hoping for immediate success, number one songs or platinum albums. I was just hopeful someone would give me a chance to make a record, and then maybe a chance to make another one.

But on that day in 2008, [my] debut single "Don't Think I Don't Think About It" hit the top of the charts at country radio. It was humbling, and it reaffirmed my belief in myself and my music. No matter what any of the doubters had to say about a Black man in country music, the Hootie singer in country music. The genre embraced [me], and it is still a dream come true almost 20 years later.

What was it like revisiting all of the old memories you delve into in 'Life's Too Short?'

It was therapy in a lot of ways. There are some parts, like about my dad, or my brother, that I didn't expect to talk so much about. But as you start revisiting the different chapters of your life, a lot comes to the surface that you might not have planned on, and you really start to process it, sometimes for the first time.

And then when we got into recording the audio book, reading it back added a whole other layer of emotion to the story. There were parts where I got choked up, and they kept that in the recording, which I think is really powerful — because it shows how much these stories mean to me.

Incubus On Revisiting 'Morning View' & Finding Rejuvenation By Looking To The Past