Photo: Anshil Popli

White Dave

news

White Dave On The Producers That Inspire Him, Why He's "Not A Rapper By Nature" & His New EP, 'Porch Sessions'

The jubilant rapper White Dave's blunted new EP, 'Porch Sessions,' which dropped on 4/20, is all about the reason for the season

If White Dave doesn't have the right beat in front of him, it's hard for him to get creative. Luckily, one transported him to the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.

Upon hearing the beat that would become "Peek," the rapper born Noah David Coogler suddenly hurtled through time and space; his street threads transformed into chain mail; his mic became Excalibur itself. "It gave me an old-school, stone-castles, moat-with-an-alligator-type vibe," he recalls to GRAMMY.com. "I was like, "Oh, man, this s**t sounds like some medieval-type, 'I'm on a horse,' jousting [scenario]. The horn felt like Merlin and wizards and s**t."

While that description may recall a D&D match on shag carpet with the shades drawn, White Dave hears the potential for the opposite: Ladies' night at the club. "It's got the crazy-ass beat; it's got the sexy-ass horn," he says of the tune’s appeal to the fairer sex. "I was like, "Let me do something for the ladies that will make them want to move and spark some imagination."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//R0bGxnTDefw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"Peek" is a slinky highlight from this month's Porch Sessions, White Dave's latest in a series of releases dropping on 4/20. The Richmond, California, rapper born Noah David Coogler has mostly gotten ink for contributing to films by his brother, Ryan, like Black Panther and Judas and the Black Messiah. But the EP's energy, vivacity and humor points to a future far afield from his brother's shadow.

White Dave takes a long toke on the cover of Porch Sessions, but if the weed imagery conjures an unmotivated couch potato, think again. His work ethic is second to none, and when the pandemic finally wraps up, expect this talented MC to make a massive splash onstage and in the studio.

"I want to connect more, build more with other artists and build up the bread," White Dave proclaims. "The best way to build up the bread is to expand and network, and that means working with other individuals who are like-minded and have a similar hustle."

GRAMMY.com gave White Dave a ring about the dynamo producers that made Porch Sessions possible, why he's had to work harder than most MCs and the inspiration behind each track on the EP.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

This is one of a few records you've released on 4/20. What's special about that day to you?

Brand reinforcement, brother. Brand reinforcement. I'm a fan of weed. My fans and people who listen to me are fans of weed. I felt like it would be not only on brand but a nice gift to connect with the fans on 4/20, the day of herb. It gives them something to look forward to every year.

I know if my favorite artist promised that they'd release something every year on 4/20, man, I'd be kept in. It's a good way to connect with the audience and give back to the people.

What was your approach for Porch Sessions as opposed to some of the other 4/20 albums?

Typically, if I'm making an EP, I just sit down, get a couple of beats together and start writing. What makes this a little bit more special is that I linked up with some new producers that I hadn't worked with before. Anytime I work with new producers, I always get excited because working with new people unlocks new creative energy.

That's why DP [Beats] and Beats By Holly are the two new producers I linked up with for the EP. They inspired me, man. Of course, I've got Boom production on there, but they really drove it home for me. I've got J-Mac vibing to the production as well. They all inspired me to make these records.

I made a bunch of records, we trimmed the fat and I've got these five records I felt could stand on their own and were an accurate representation of me. So, we put them together and got it out.

What do you specifically appreciate about these producers?

Man, anytime I turn on a beat and it sounds fresh—it doesn't sound like anything else that I've heard—I try to remain in my lane, you know? Kind of carve out my own sound, my own kind of lane. All the beats on the project, in my opinion, were really unique and kind of captured different artistic levels and sides of me.

Anytime I'm able to get inspired by the production, it makes the studio session that much easier. Sometimes, I'll be writing to a beat and the beat doesn't move me; the production doesn't move me. Which isn't to say that it's a bad beat; it just doesn't connect to me the way I'd like for it to.

The producers and production on this project spoke to me and I was able to sit down and get some nice records together. I'm excited about the feedback and I'm excited for people to be introduced.

It seems like it's not just the sound of the record; it's putting the right beat in front of you so the creativity can flow. The producer's role applies throughout the music-making process.

Absolutely. I'm not a rapper by nature. I talk about this all the time; I love making beats. And because I'm not a rapper by nature, I've got to really, really, really rock it with the production because that will encourage and unlock that rap energy.

I grew up making beats, so when I hear beats, I'm listening to it like a solo producer: "Yeah, yeah, yeah, this is tight, this is tight." Oftentimes, I hear a beat and it unlocks that rapper mentality, that rapper mind-state. Those are the beats that I usually put on my EPs and albums: the beats that unlock that type of creativity.

These producers, they did it for me. I'm so excited about the sound of this project. And it sounds so much different than all my other 4/20 projects. All my 4/20 projects sound different, and that's what I'm definitely going to do as an artist: continue to grow, continue to mature, continue to push the boundaries.

Photo: Anshil Popli

You said you're not a rapper by nature. Do you mean to say you're technically limited in some way? Which is not a slight, because many of my favorite singers and guitarists are very technically limited.

Yeah, absolutely. Man, I grew up with acts who can rap. And when I say "rap," I mean you can turn on anything and they just bar the s**t up. I never grew up with the innate ability to just rap off-the-cuff.

Of course, I could freestyle with friends and s**t like that and X, Y and Z, but I had to really sit down and learn and teach myself how to structure bars and how to ride the beat and how to format songs—hook, chorus, bridge, intro and outro. I had to really sit down and learn the fine technique and intricate detail of being a rapper.

For me, the way my brain works, producing is second nature because I've been banging on tables and making melodies and cutting rhythms since I came into the Earth. But layering words over beats was something that I had to teach myself.

I started freestyling and rapping and putting bars down when I was 10 or so, but I didn't record my first record until I was 12 years old. That's because I was teaching myself. Making beats came so easy, man. I don't even know how to explain it.

I had a keyboard at my house when I was growing up and I used to play on that thing all night, making beats, just because it connected. It sounds that way connected to my brain. But for me, personally, rapping activates a whole different hemisphere of my brain. That's why I'm always thankful when I meet and work with producers that activate that.

Technically speaking, what's the most important aspect of rapping?

That's a layered question, and I'll tell you why: It's different for every artist. I say that because as a rapper, you've got your tone as a whole—just how you sound on a record. Then, you've got your delivery. You've got your pitch. You've got how you're rapping—if it's super laid-back, if it's super amped-up. If you're changing your voice. All of these things factor into how your message is perceived.

Looking at myself as an artist, I'm a huge fan of how I deliver my raps. If something I'm saying has a comedic edge, it's kind of funny, it's kind of nonchalant, it's how I deliver it, too. I'm a real big fan of how you're delivering the raps.

Let me give you an example. I'm a huge 21 Savage fan. And the reason I'm a huge 21 Savage fan is because his beats are easy to follow along with. But that doesn't make them simple, you know? Having the ability to rap an entire song and have people rap with you bar-for-bar, not everyone can do that.

On the other hand, you've got artists like Eminem. Massive Eminem fans are able to rap along with him, but his delivery and technique is a little bit more intricate and precise. That's not to say one is better than the other; they just do things differently.

For me, personally, I think how I deliver the bars is not necessarily what sets me apart, but what makes me a little bit unique. A lot of artists sound similar but you can distinguish between them because of how they're presenting to you.

I'm a huge fan of Kendrick [Lamar]'s delivery. Huge fan of Kendrick's delivery. And it's because it travels a fine line of God-tier technicality but still resides in that realm of ear candy. Maybe it's not easy to rap along to, but easy to follow along with.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//eUP3-AgMVlY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Let's go through the tunes on Porch Sessions. What can you tell me about "That's a Play"?

"That's a Play" is probably the newest record on there. Originally, my 4/20 albums were only four tracks. I kind of like the theme of four tracks.

But my boy J-Mac, who's a producer out of North Carolina, I met him a couple of years ago. He always sends me beats here and there. He sent that over and was like, "Hey, I made this beat, man. It's kind of got a cushy pop sheen to it. It's not a pop record, but it's got a poppy feel, almost."

I turned on the beat and, like I was saying earlier, it activated that part of the brain. It activated that lyric-writing portion, that "I have words to say" portion. I laid down a rough hook and I was like, "This might be a jam!" It kind of had a mellow-hype thing. You can either turn it on and chill to it or turn it on and get hype to it.

When I finished the record, I sent it over to my management team and they were like, "Aye, this record's tight. We want to put it on Porch Sessions. This has to go on there. This is a hell of record."

Right on. How about "Hotel Motel"?

"Hotel Motel" is one of my personal favorites. My boy Boom, who's a phenomenal producer, man—phenomenal producer—sent that beat over. I'd been telling him, "Say, bro, we need more uptempo shit, some party-type s**t!"

He sent the beat over, I was chewing on it for a bit, and I actually came up with a couple of different hooks for it. But I said, "We need something that will represent Bay Area culture a little bit." When I was growing up, we used to have hotel parties. And depending on the crowd you were hanging with, it was either a hotel party or a motel party.

That energy and that type of vibe, I wanted to capture that on the record. If you're from the Bay, you recognize that this is the Bay Area life. That is the Bay Area anthem for the album, if you will. I wanted to make sure I had at least one on there that was like that.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//i-38UcStjLQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Tell me about "Odor."

It speaks for itself, man. If you're going to be dropping a project every 4/20, you've got to make sure you have a type of weed anthem on there. "Odor" is also produced by Boom. Boom is the GOAT. He's the backbone to my sound. He keeps me motivated.

Once again, Boom sent that beat over and I listened to it and I was like, "Yo, that s**t, that is such a unique sound." There is nobody rapping over these types of beats. I feel like that's what kind of separates me from everybody else. They always have a nice groove on them.

I hate when I turn on a beat and the beat's tight but it's got too much going on. You can overproduce. There's such a thing as overproducing. Boom does the exact amount every time—the perfect amount every time. For example, "Hotel Motel," it took me a while to get that song where I needed it to be. "Odor" wrote itself. He sent it over and I was like, "OK, this is the weed anthem. Now let's get it going."

I feel like "odor" is a word that kind of has negative connotations. People think of an odor as a negative thing. For me, an odor isn't necessarily a bad smell. It's a distinct smell. So I was like, "'Odor' is a good word for trees." Some people think weed stinks and other people think it's one of the best smells on Earth.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//bNVF9T6sfpY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

And how about "Peek"?

"Peek," man! Ah, man! One of my personal favorites from the project.

Beats By Holly—he's the guy on IG, man. He reached out to me a couple of months ago and goddamnit, man, he sent me, like 80 beats, man. Which I love. Because not only does it show me that you're serious about your craft; you're serious about working.

I can't tell you how many times somebody would hit me on IG telling me, "Let's do some work," and that's it. That is the full extent of the conversation. Holly hit me, he said, "Let's do some work," I said "Bro, let's go," and he sent me 80 beats the next day. Eighty beats!

And me, I'm very picky. Beats can be tight, but they may not speak to me. I'm going through the beats, brother, and I came up on the beat for "Peek." I was like, "Oh, man, this s**t sounds like some medieval-type, 'I'm on a horse,' jousting [scenario]." I felt like I was in a suit of armor. The horn felt like Merlin and wizards and s**t. It gave me an old-school, stone-castles, moat-with-an-alligator-type vibe.

I didn't come up with the words right off the bat, but the beat was talking to me. So, I said, "Let me chew on this for a little bit." I'm chewing on the beat for a little bit and I'm realizing … Something I think about all the time is that I'll be hovering over my listener's breakdown—not my streams, but my listener's breakdown—and it sounds funny, but I only have, like, eight percent female listeners.

I'm like, "Let me see if I can do something for the ladies, but not, like, super, super, super down the line. I've got R&B records for the ladies on the albums and s**t, but I was like, "Let me do something for the ladies that will make them want to move and spark some imagination," you know? "Peek" is my song that's for the ladies.

It's not a sex song, but it's kind of sexy, you know what I mean? It's got the crazy-ass beat; it's got the sexy-ass horn. It's got a certain feel to it. The way I did the hook, it's got a swing. Sometimes, I write my bars to be very precise and on-point because that's how I taught myself, and other times, I'll do something with a little more swing.

And the hook on "Peek," if you're looking at it from a musical standpoint, is a little more bluesy, a little more funky, because it lacks traditional structure. It holds notes, it starts at off times, and it gives the song a unique kind of swing when it gets to the hook portion. And that's what I really like. That's what I really f**k with.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//7u00vRrqS3s' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Lastly, we've got "Brand New."

Yeah, yeah, that's DP, man. French producer, bro. He hit me about doing some work, brother, and he sent over, like, 10 beats. So, I'm going through them, I'm going through them, and I pulled up on this beat. I was like, "This s**t is wild!" I loaded it into ProTools, man, and once again—and I can't make this s**t up, bro—the song wrote itself.

It gave me this sliding-type feeling. Where I'm just sliding. I'm in a good mental space, I'm in a huge spiritual space, and I'm just vibing out. "Brand New" always felt like a phrase that was meant for rebirth. I'm reinvigorated. I'm full of fresh, new energy. That's what I wanted to capture on that record.

The guitar on that record is hella sexy. The bass gets to kickin'. It's kind of an aggressive record, and I don't have an aggressive sound, so that kind of gives it a layer. It was funny because, originally, that was going to be the opening track. But at the last minute, we moved "That's a Play" to the beginning and we moved "Brand New" to the end.

Now that I look at it, I'm like, "God, we should have put 'Brand New' at the front," just because of that energy. It's got a very unique energy that no other song has.

When things settle down, what are your plans for the remainder of 2021 and 2022?

I want to get on stage, man. I don't want to oversell myself, but I put on a pretty good live show. I want to do it safely. I know COVID is still poppin'. But the biggest thing, man, is I want to continue to make records. I want to branch out and make records with more artists.

It's more difficult to do as an independent artist—working with bigger artists and with bigger budgets and s**t. But I've made moves here and there, so I want to just continue to grow. Continue to hone my craft. Learn the industry better. Also, do more production. I still make beats. I make beats every day.

At the moment, I only produce for myself. I have a couple of artists I produce for here and there, but for the most part, I only produce for myself. I want to venture out more. I want to connect more, build more with other artists and build up the bread.

The best way to build up the bread is to expand and network, and that means working with other individuals who are like-minded and have a similar hustle. I want to continue to grow, get better, get smarter, mature and continue to make steps.

I really appreciate your drive and commitment to improve as an artist. It's inspiring stuff.

Oh, for sure, man. If you're not trying to get better, what are you doing?

Photo: Giovanni Mourin

interview

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

Over a decade after he released 'King of the Mischievous South Vol. 1,' Denzel Curry is back with 'Vol. 2.' The Miami rapper details his love of Southern hip-hop, working on multiple projects, and the importance of staying real.

Denzel Curry isn’t typically one for repetition. His recent run of critically acclaimed projects have all contrasted in concept and musicality.

The Miami Gardens native has cascaded through boom-bap, synth-soaked trap metal, and cloud rap throughout his catalog. But on his upcoming project, King of the Mischievous South Vol. 2, Curry returns to the muddied, subwoofer-thudding soundscape that he captured on the first installment back in 2012.

Curry was just 16 when he released King of the Mischievous South Vol. 1 Underground Tape 1996]. "I was a kid, man," Curry tells GRAMMY.com. "I was just trying to emulate my favorite rappers at the time who really represented the South. That was pretty much what I was on at the time – the Soulja Slims, the No Limits, but mostly Three 6 Mafia. And then I just put Miami culture on top of that."

Curry first explored the rough-cut "phonk" of Southern acts like DJ Screw and Pimp C as a teenager. His first mixtape, King Remembered Underground Tape 1991-1995, caught the attention of then-rising rapper and producer SpaceGhostPurrp. He shared Curry’s project on his social media accounts, making him an official member of South Florida’s Raider Klan.

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

The now-defunct group is well behind Curry, who’s ascended from the infancy of his early SoundCloud days to mainstream success. But the rapid-fire delivery and hazy, rough-cut sounds of early Southern rap are still soaked into his musical fibers.

Reignited by the same musical heroes that led to Vol. 1, Curry is comfortable in old sonic form. Vol. 2's lead singles "Hot One" (feat. A$AP Ferg and TiaCorine) and "Black Flag Freestyle" with That Mexican OT fully capture the sharp-edged sound that stretched from Port Arthur, Texas to the Carolinas.

The rapper wanted to go back to the KOTMS series nearly a decade ago, but other projects and outside ventures derailed his return. "I tried to do this thing multiple times," Curry tells GRAMMY.com. "I remember revisiting a [social media post] from 2015 that was like, ‘KOTMS Vol. 2055 is now going to be called Imperial.’ I’ve been trying to do this for the longest."

A string of bouncy, syrup-pouring, and playalistic Southern trap songs led him back to familiar grounds. The new 15-song capsule features Juicy J, 2 Chainz, Project Pat, That Mexican OT, Maxo Kream, and others inspired by the same pioneers that fall below the Mason-Dixon line.

GRAMMY.com sat down with Curry before the release of King of the Mischievous South Vol. 2 on July 19. The "Ultimate" rapper revealed his "Big Ultra" persona, his ability to crank out hits from his bedroom, and his recent discoveries being "outside."

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

What inspired you to revisit the 'King of the Mischievous South' series?

I was making two projects at once, and there was a through-line from the second half of the project. The second one I was working on kind of just manifested itself into what it is today, 12 years later. And it’s called King of the Mischievous South Vol. 2 because it has the same sonics as the first one.

You mentioned Three 6 Mafia being a big inspiration for Vol. 1. But what about Vol. 2?

The first KOTMS was obviously Three 6 Mafia, and then Lord Infamous was really the person I looked up to, God rest his soul. I get my rap style from him — the rapid flows and stuff like that. You can even hear it on "Walkin’" and "Clout Cobain." But since I’m from Miami, I’m talking about stuff that predominantly happens in Miami. And I’m influenced by Soulja Slim, Master P, DJ Screw, UGK, Trina, Trick Daddy, and Rick Ross.

How did you juggle the two different projects at once?

When I wasn’t working on one project, I was working on the other one. Sometimes I would be working on the same two projects on the same day. I was like, If this one won’t see the light of day until next year, this one has to hold fans over. And the one that was supposed to hold fans over ended up having a crazy through-line.

What were the studio sessions like?

When it came down to the production, I was just making these songs on the fly. A couple came out of Ultraground sessions, but the majority of the songs were made in my bed — just how it was with the first one. "Hot One" was made in my house downstairs, and "Hit The Floor" was made in a random room in an AirBnb. And I think the rest of the songs were made in an actual studio.

I was just flowing, doing my thing, and figuring things out. I was working on one project, and when I wasn’t getting called back to the studio, I was working on another one on the side. The grind didn’t stop.

Was there an element or feature that you really wanted to explore?

I just knew I wanted certain rappers to be featured on [project]. When I was working on "Set It," I originally wanted PlayThatBoiZay. But he didn’t get the record done or whatever the case may be. So, I sent it to Maxo Kream, and he ended up just doing it. And when I made "Wish List," I got Armani White on it. Me and him came off of doing "Goated," so getting that record done was really simple. He pulled up to the studio and he said, "This is tight," and then jumped on the record.

Some stuff didn’t make the cut because we couldn’t get certain people. But the majority of the stuff that made the cut, we were like, "Yes, we did that." Then having people like Ski Mask the Slump God, 2 Chainz, Project Pat, and Juicy J — all these guys played a role. I’m getting people from the South, whether they’re from Texas, Florida, or the Carolinas. And even people outside of the South, like A$AP Ferg and Armani White, they’re all influenced by the same artists.

Learn more: A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

Your persona on the album, "Big Ultra." Break that down for me.

This is how the name came about — my boy’s nickname is Mr. Don’t Fold. It’s kind of a play on "Mr. Don’t Play," so we came up with "Big Ultra" because I’m doing "ultraground" stuff. It wasn’t on some superpower s—, it’s just me, pretty much. It’s how I wanted to be presented on this tape. It’s just me at the end of the day, it’s no persona.

You’ve been in the rap game for a while. Do you consider yourself a veteran?

I think I’m mostly in a formation period because my best years haven’t even happened yet. I feel like I’m just getting my reps in, preparing myself for my 30s. You know, going through the bulls—, having good times, having bad times.

By the time I get to 30, 35, and 40 — God willing — I could have a fruitful career and not be backtracked by dumb s—. I see myself as someone with a lot to offer because I’m still young.

Do you care about garnering more fame or acclaim? Or is there no need for it?

All my projects are critically acclaimed. The main thing is staying good at what I do. That comes with a lot of effort, a lot of studying, and a lot of work. I take pride in my job and I have fun making music.

I think the hardest part is putting myself out there and being visible. I’m starting to understand that’s what I had to do. I got asked the same question five times in a row about when my album was dropping. I’ve been saying July 19 for the longest. Like, people really haven’t been paying attention? C’mon, bro.

What do you feel is the next step?

I’m just trying to be more visible where the younger generation is at. Most people know me for "Ultimate," "Clout Cobain," or the [XXL Freshman Class] Cypher if I’m being totally real with you. But in due time, everybody has blessings in certain parts of their career. And I’ve been blessed to have a career this long.

All I have to do is just deliver, be real with myself, and do what I have to do. I got to lean into being outside. I didn’t know who messed with me or who liked my stuff until I started going outside and talking to people. You never know who rocks with you until you're outside.

As far as the music and experience, where does the album rank for you?

I didn’t think about where I’d rank this. We had a whole decade of producing great records, and people look forward to the album experience more than the single when it comes to me. This is what it is, and I just want people to enjoy it. It’s not something to put too much effort or thought into. It’s something you can bump into the club, or you could go to a show and turn up to it. That’s where I’m at with it.

Are there any other sounds or genres you want to explore?

It’s going to happen when it’s supposed to happen naturally. But I do want to explore pop and R&B a year from now. I want people to be able to sing my songs and stuff like that.

Latest Rap News & Music

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

On Rakim's 'G.O.D's Network (REB7RTH)' The MC Turned Producer Continues His Legacy With An All-Star Cast

5 Ways Mac Dre's Final Living Albums Shaped Bay Area Rap

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

Photo: Oye Diran

interview

Meet Derrick Hodge, The Composer Orchestrating Hip-Hop's Symphony

From Nas' 'Illmatic' to modern hip-hop symphonies, Derrick Hodge seamlessly bridges the worlds of classical and hip-hop music, bringing orchestral elegance to iconic rap anthems.

Over the last 50 years, hip-hop culture has shown it can catalyze trends in fashion and music across numerous styles and genres, from streetwear to classical music. On June 30, Nas took his place at Red Rocks Amphitheater in a full tuxedo, blending the worlds of hip-hop and Black Tie once again, with the help of Derrick Hodge.

On this warm summer eve in Morrison, Colorado, Nas performed his opus, Illmatic, with Hodge conducting the Colorado Symphony Orchestra. The show marked a belated 30-year celebration of the album, originally released on April 19, 1994.

As Nas delivered his icy rhymes on classics like "N.Y. State of Mind," "Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)," and "Halftime," the orchestra held down the beat with a wave of Hodge's baton. The winds, strings, and percussion seamlessly transitioned from underscoring Nas's lyrics with sweeping harmonic layers to leading melodic orchestral flourishes and interludes. For the album's final track, "Ain't Hard to Tell," the orchestra expanded on Michael Jackson's "Human Nature," expertly sampled originally by producer Large Professor.

Derrick Hodge is a pivotal figure in modern music. His career spans writing and performing the famous bassline on Common's "Be," composing for Spike Lee's HBO documentary "When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts," and his own solo career that includes his latest experimental jazz album, COLOR OF NOIZE. Hodge also made history by bringing hip-hop to the Kennedy Center with orchestra accompaniments for Illmatic to celebrate the album's 20th anniversary in 2014.

"That was the first time hip-hop was accepted in those walls," Hodge says sitting backstage at Red Rocks. It was also the first time Hodge composed orchestral accompaniments to a hip-hop album.

Since then, Hodge has composed symphonic works for other rappers including Jeezy and Common, and is set to deliver a symphonic rendition of Anderson .Paak's 2016 album, Malibu, at the Hollywood Bowl in September.

Hodge's passion for orchestral composition began when he was very young. He played upright bass by age seven and continued to practice classical composition in his spare moments while touring as a bassist with Terence Blanchard and Robert Glasper. On planes. In dressing rooms. In the van to and from the gig.

"It started as a dream. I didn't know how it was going to be realized. My only way to pursue that dream was just to do it without an opportunity in sight," Hodge says. "Who would've known that all that time people were watching? Friends were watching and word-of-mouth."

His dedication and word-of-mouth reputation eventually led Nas to entrust him with the orchestral arrangements for Illmatic. He asked Hodge and another arranger, Tim Davies, to write for the performance at the Kennedy Center.

"[Nas] didn't know much about me at all," Hodge says. "For him to trust how I was going to paint that story for an album that is very important to him and important to the culture, I have not taken that for granted."

Read more: How 'Illmatic' Defined East Coast Rap: Nas’ Landmark Debut Turns 30

Those parts Hodge wrote for the Kennedy Center are the same parts he conducted at Red Rocks. Over a decade later, he channels the same drive and hunger he had when he was practicing his compositions between gigs. "I hope that I never let go of that. I feel like these opportunities keep coming because I'm approaching each one with that conviction. Like this could be my last."

Before this latest performance, GRAMMY.com spoke with Hodge about bridging the worlds of classical and hip-hop, influencing the next generation of classical musicians, and how his experience as a bassist helps him lead an orchestra.

Throughout history, orchestral music has been celebrated by the highest echelons of society, whereas hip-hop has often been shunned by that echelon. What is it like for you to bring those two worlds together?

I love it. I've embraced the opportunity since day one. I was a young man showing up with Timberlands on and cornrows in my hair, and I knew the tendency to act and move in a certain perception was there. I knew then I have to represent hope in everything I do. I choose to this day to walk with a certain pair of blinders on because I feel like it's necessary. Because of that I never worry about how the classical world perceives me.

Oftentimes I'll stand before them and I know there may be questions but the love I show them, what I demand of them, and how I show appreciation when they take the music seriously…almost every situation has led to lifelong friendships.

I believe that's been part of my purpose. It's not even been to change minds or change perceptions. In serving the moment, even when people have preconceptions, they're in front of me playing music I wrote. How do I serve them best? How do I bring out the best in them just like I'm trying to bring out the best in the storyline of a hip-hop artist that may not relate to their story at all? The answer is just to be selfless. That's eliminated the distraction of trying to convince minds.

With that unifying principle, would you consider conducting the orchestra the same thing as playing bass with Robert Glasper?

The way I try to be selfless and serve the moment, it's no different. Maybe the skillset that's required. For example, conducting or working within a framework of composed music requires a certain way of making sure everybody's on the same page so we can get through these things on time and keep going. But I serve that moment no differently than when myself and Robert Glasper, Chris Dave, Casey Benjamin RIP, are creating a song in the moment.

I actually don't even think about how one thing is affecting the other. I will say the beauty of the bass and the bassists that have influenced me — from Ron Carter to the great Marcus Miller, Victor Wooten — is the way they can stand out while never abandoning the emotion of the moment. Remembering what is perceived as the role of the bass and how it glues things in a unique way. Harmonically and rhythmically. Being aware of the responsibility of being aware of everything.

I think that's one thing that's carried over to orchestrating and thinking about balances and how to convey emotion. I think some things are innate with bassists. We're always navigating through harmony and having a conversation through a lens of placement with drums. Placement with the diction if they're singers or rappers. There are a lot of decisions bass players are making in the moment that we don't even think about. It's just secondhand. But it's how are we serving what's necessary to make the conversation unified. I think that's one thing that's served me well in composition.

What's one song you're particularly excited to dive into for the Anderson .Paak arrangements?

So I'm intentionally not thinking in that way because we decided to treat it like a movie. Start to finish no matter what. With that in mind, I'm trying to approach it as if the whole thing is an arcing story because I didn't realize the succession of how he placed that record was really important to him.

**Hip-hop is often a very minimalist genre while an orchestra is frequently the opposite with dozens of instruments. How do you maintain that minimalist feel when writing orchestra parts for hip-hop albums like Illmatic?**

I'm so glad you asked that because that was the biggest overarching thing I had to deal with on the first one. With Nas. Because Illmatic, people love that as it is. Every little thing. It wasn't just the production. Nas's diction in between it, how he wrote it, how he told the story, and the pace he spoke through it. That's what made it. So the biggest thing is how do I honor that but also try to tell the story that honors the narrative of symphonic works? [The orchestra is] fully involved. How do I do things in a way where they are engaged without forcing them?

Illmatic was a part of my soundtrack. So I started with the song that meant the most to me at that time: "The World is Yours." That was the first piece I finished, and I emailed Pete Rock and asked "How is this feeling to you?" If the spirit of the song is speaking to him then I feel like this is something I can give to the people no matter how I feel about it. And he gave the thumbs up.

So instead of overly trying to prove a point within the flow of the lyrics, how do we pick those moments when the orchestra is exposed? Let them be fully exposed. Let them tell a story leading into that. Make what they do best marry well into what Nas and the spirit of hip-hop and hip-hop sampling do best. And then let there be a dance in between.

That first [Illmatic] show was a great experiment for me. I try to carve out moments whenever I can. Let me figure out what's a story that can combine this moment with this moment. That's become the beauty. Especially within the rap genre. To let something new that they're not familiar with lead into this story.

*Derrick Hodge conducts the Colorado Symphony Orchestra at Red Rocks* | Amanda Tipton

The orchestra is just as excited to play it as Nas is to have them behind him.

And that reflects my story. I try to dedicate more time to thinking about that, and that normally ends up reciprocated back in the way they're phrasing. In the way they're honoring the bowings. In the way they're honoring the breaths that I wrote in for them. They start to honor that in a way because they know we're coming to try and have a conversation with these orchestras. That's one thing I try to make sure no matter what. It's a conversation and that goes back to the moment as well.

I've seen other composers put an orchestral touch on hip-hop in recent years. For example, Miguel Atwood-Ferguson wrote orchestral parts to celebrate Biggie's 50th birthday. Would you say integrating an orchestra into hip-hop is becoming more popular?

It has become popular, especially in terms of catching the eyes of a lot of the different symphonies that might not have opened up their doors to that as frequently in the past. These opportunities — I appreciate the love shown where my name is mentioned in terms of the inception of things. But I approach it with a lot of gratitude because others were doing it and were willing to honor the music the same. There are many that wish they had that opportunity so I try to represent them.

With these more modern applications of orchestral music, I feel like there will be an explosion of talent within the classical realm in the next few years. Kids will think it's cool to play classical again.

The possibility of that just brings joy to me. Not just because it's a spark, but hopefully the feeling in the music they relate to. Hopefully there is something in it, aside from seeing it done, that feels that it relates to their story. I have confidence if I'm true to myself, hopefully, each time in the music it's going to feel like it's something relevant to the people. The more I can help foster platforms where people are free to be themselves, and where they can honor the music—I hope that mentality becomes infectious.

More Rap News

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

On Rakim's 'G.O.D's Network (REB7RTH)' The MC Turned Producer Continues His Legacy With An All-Star Cast

5 Ways Mac Dre's Final Living Albums Shaped Bay Area Rap

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

Photo: Amy Lee

list

5 Rising L.A. Rappers To Know: Jayson Cash, 310babii & More

From San Diego to the Bay Area, Seattle and beyond, the West Coast bursts with talent. Los Angeles is at the heart of this expanse, and these five rappers are just a few who are showcasing the vibrant sounds of West Coast hip-hop.

GRAMMY winners Kendrick Lamar and Mustard have long repped their California roots. Earlier this summer, their powerhouse anthem "Not Like Us" brought West Coast rap back to its roots and shone a global spotlight on the scene.

Lamar and Mustard are at the forefront of a renaissance in West Coast rap. Their shared roots in Southern California cities — Mustard from Los Angeles and Kendrick from Compton — adds authenticity and resonance to their partnership. Their undeniable chemistry was on display in the video for "Not Like Us," which received a million views less than an hour after its release.

Mustard's signature beats and Lamar's profound lyricism has resurfaced the sound and culture that makes West Coast rap so unique and paved the way for a new generation of artists. All signs suggest that another impactful collaboration may appear on Mustard's upcoming album, Faith of A Mustard Seed.

Learn more: A Guide To Southern California Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From L.A. & Beyond

Kendrick Lamar headlined the electrifying Pop Out concert on Juneteenth, which also featured sets from Mustard and DJ Hed. The event saw a handful of L.A. rappers, opening for Lamar in a showcase of the vibrant talent that defines the region's rap scene.

The West Coast is a vast reservoir of talent, stretching from the Bay Area to Seattle. At the heart of this creative expanse is Los Angeles, which brings fresh perspectives, innovative styles, and renewed energy to hip-hop, ensuring the genre thrives. With the stage set for these newcomers to shine, it's the perfect time to take a closer look at some of the rising talents poised to impact the rap scene. While this list only scratches the surface, it offers a glimpse into the diverse and exciting talent from SoCal, the epicenter of the West.

Blxst

Arising from Los Angeles, Blxst initially played the background as a producer but soon demonstrated his ability to excel across all facets of music creation. Blxst's breakout moment came with his platinum-certified single "Chosen," which solidified his place in the music industry. His collaboration on Kendrick Lamar's "Die Hard" from Mr. Morale And The Big Steppers further showcased his skill for crafting hooks that elevate tracks, resulting in two GRAMMY nominations.

As he prepares to release his debut album, I'll Always Come Find You on July 19, Blxst stands at a pivotal point in his career. With a great resume already to his name, his forthcoming album promises to showcase his undeniable talent and leave a lasting impact on the West Coast music scene.

Bino Rideaux

Bino Rideaux is a South Central native and frequent collaborator with the GRAMMY-winning rapper Nipsey Hussle. He is the only artist to have a joint project with Hussle, No Pressure, released before the prolific rapper's untimely death. Rideaux has hinted at having a treasure of unreleased music with Hussle, saved for the perfect moment and album.

Rideaux is known for creating tracks that get the city outside and dancing. He has made three beloved projects with Blxst, titled Sixtape, Sixtape 2, and Sixtape 3 resulting in sold-out shows and a special place in West Coast Rap fans' hearts. Endorsed by industry heavyweights like Young Thug, Rideaux continues to carve his path at his own pace. His journey is nothing short of a marathon, echoing the enduring legacy of his mentor.

Kalan.FrFr

Kalan.FrFr, whose name stands for "For Real For Real," is an artist whose music is as genuine as his name suggests. Growing up in Compton and Carson, Kalan.FrFr has always stayed true to his roots, and exudes the unyielding confidence essential to making it in the City of Angels.

His breakthrough mixtape, TwoFr, showcased his ability to shine without major features, delivering verses with catchy hooks and melodic rap. He's shown he's not confined to one sound, delivering vulnerable tracks like "Going Through Things'' and "Never Lose You." His EP Make the West Great Again, Kalan.FrFr both proves his loyalty to his origins and highlights his versatility. Kalan.FrFr's signature punch-in, no-writing-lyrics-down style keeps his fans on their toes, ensuring that whatever comes next is unpredictable but authentic.

Jayson Cash

Jayson Cash, a rapper hailing from Carson — the same city as TDE artist Ab-Soul — stays true to West Coast rap, from his lyrics to his beat selection. Listening to Jayson Cash's music is like diving into a vivid life narrative. His prowess as a lyricist and storyteller shines through in every verse. He gives his fans an insight into his journey, making it a relatable music experience.

Cash made waves with his debut mixtape, Read The Room, and scored a Mustard beat on the song "Top Down." Two years later, their collaboration continues, with Cash writing on Mustard's upcoming album. Though often seen as an underdog, Cash is not to be underestimated, earning cosigns from West Coast legends like Suga Free and Snoop Dogg. His latest project, Alright Bet, includes a notable feature from Dom Kennedy.

310babii

310babii has achieved platinum-selling status at just 18 years old, while successfully graduating high school. Yet 310babii's career began in seventh grade, when he recording songs on his phone showing early signs of motivation and creativity. His 2023 breakout hit "Soak City (Do It)" quickly gained traction on TikTok — and caught the ears of Travis Scott and NFL player CJ Stroud.

As the song grew in popularity, it led to a remix produced by Mustard, who invited the Inglewood native to join him onstage during his set at The Pop Out. 310babii's innovative spirit shines through in his distinctive visuals, exemplified by the captivating video for his song "Back It Up." His recent debut album, Nights and Weekends, released in February, underscores his evolving talent and promise within the music industry.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

Photo: Aaron J. Thornton/GettyImages

news

New Music Friday: Listen To New Releases From Katy Perry, Eminem, Nelly Furtado & More

As temperatures rise, chill out with these fresh tracks, albums, and collaborations from Nelly Furtado, One OK Rock, Uncle Kraker, and more, all released the week of July 12.

As summer rolls on, more tracks from artists across all genres continue to drop, and we couldn't be more excited. With album releases from John Summit, HARDY, OneRepublic, and Cat Burns to fresh singles from collaborations including Alesso and Nate Smith, July 12 brings a handful of new music to enjoy.

As you stroll through the weekend, make sure to check out these nine musical projects:

Katy Perry — "Woman's World"

Serving as the lead single from 143, her first studio album since 2020, Katy Perry releases "Woman's World," a new pop track celebrating girl power and womanhood. Perry wrote the track alongside songwriter Chloe Angelides and producers Dr. Luke, Vaughn Oliver, Rocco Did It Again!, and Aaron Joseph.

Initially teasing the track through social media, the song drew attention from pop fans globally. The lead single from 143 marks both a comeback and a new era for the American Idol judge. "I set out to create a bold, exuberant, celebratory dance-pop album with the symbolic 143 numerical expression of love as a throughline message," Perry explains in a press statement.

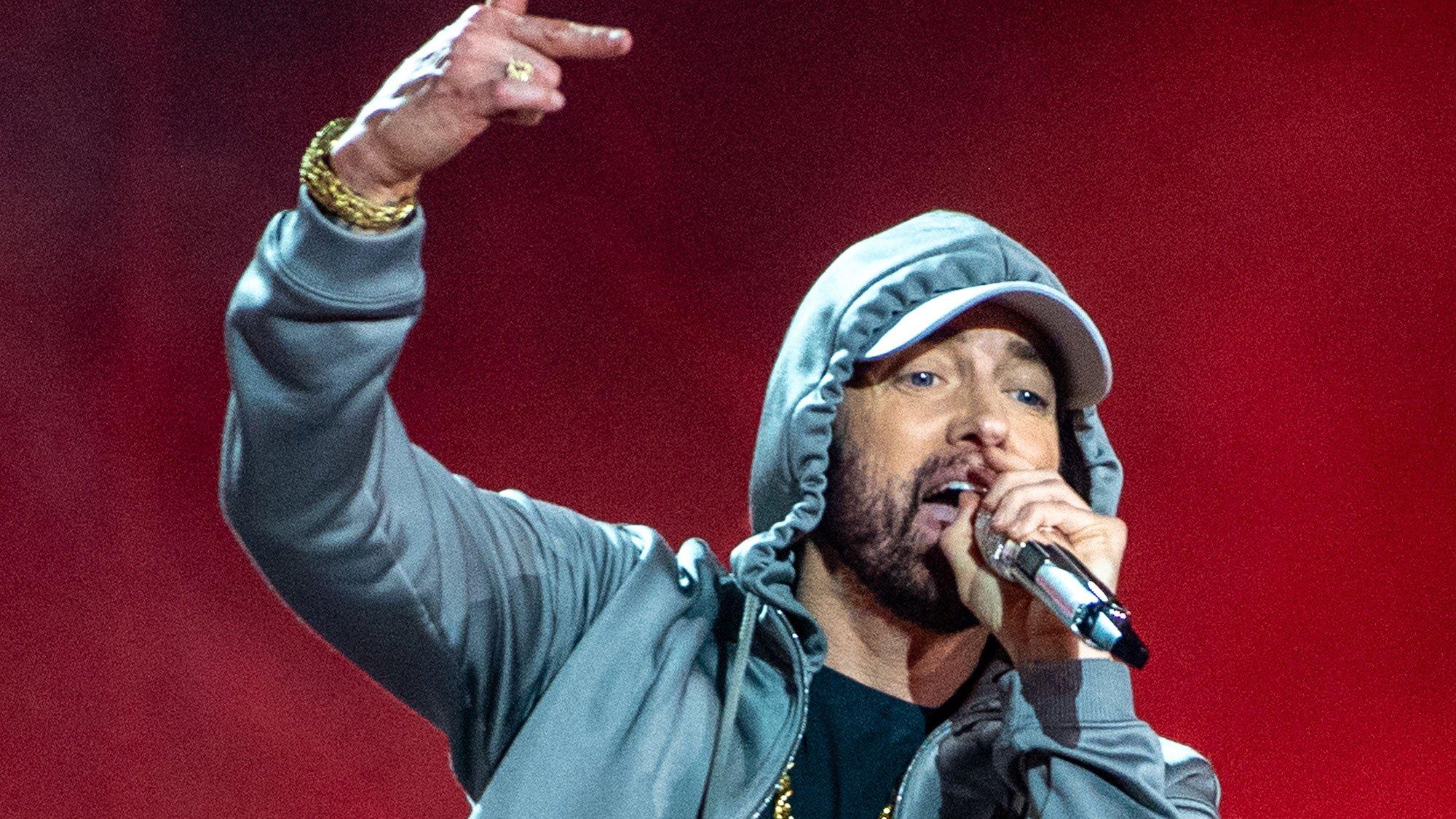

Eminem — 'The Death of Slim Shady (Coup De Grâce)'

Guess who's back? Eminem returns with his twelfth studio album, The Death of Slim Shady (Coup De Grâce). The album appears to be his last project before retiring his notorious alter ego, Slim Shady.

A standout track on the album is "Guilty Conscience 2," a sequel to the 1999 collaboration with Dr. Dre. Leading up to the album release, Eminem dropped two singles, "Houdini" and "Tobey," featuring Big Sean and BabyTron. The album is both a blast from the past and a revived representation of the renowned Detroit-raised rapper.

Nelly Furtado — "Corazón"

Premiering the song at her Machaca Fest set, Nelly Furtado returns to music with "Corazón," the lead single off her new album 7. The track is an upbeat dance song with lyrics in both Spanish and English, along with drums and flutes that bring it to life. The track was two years in the making, according to Furtado on Instagram.

"The essence of the song is that we're just out here living and trying to do our best," Furtado told Vogue. "Even when we make mistakes, it's coming from the heart. When it comes from the heart, it's never a mistake."

7 is set to captivate both loyal fans and new listeners. Centered around the vibrant theme of community, Furtado felt an irresistible pull toward creating new music, inspired by the diverse communities around her. The spirited energy of the DJ community that breathes new life into her pop classics to this day and the passionate online community yearning for her return, spurred by her collaborations with Dom Dolla and Tove Lo and SG Lewis, have both played a crucial role in Furtado's renewed artistic journey.

Clairo — 'Charm'

Amidst the viral resurgence of her 2019 track "Bags" on TikTok, indie sensation Clairo unveils her eagerly anticipated third studio album, Charm. Co-produced with GRAMMY-nominated Leon Michels of El Michels Affair, this enchanting project underscores a striking blend of musical artistry and innovation.

"I want afterglowing, and when I call a car / Send me eyes with the knowing that I could pull it off," she sings in "Sexy To Someone," the lead single from the album. Putting introspective lyricism at the forefront of all her projects without sacrificing quality instrumentals, this album is no exception.

Alesso & Nate Smith — "I Like It"

In this genre-crossing collaboration, electronic artist Alesso joins forces with country singer Nate Smith on their new single, "I Like It." Though an unexpected blend of styles, the song blends elements from both artists' sounds, seamlessly combining country and dance as they proudly declare, they "like it like that."

With Alesso's electrifying instrumentals perfectly complementing Smith's spirited country vocals, the track captures the essence of summer in a song and is set to make waves throughout the season.

One OK Rock — "Delusion:All"

Featured as the official theme song for the upcoming movie "Kingdom IV: Return of the Great General", Japanese rock band One Ok Rock releases "Delusion:All." The upbeat, cinematic track is the band's latest contribution to the "Kingdom" movie soundtrack series, following their 2019 song "Wasted Nights."

"It's been a while since we wrote 'Wasted Nights' for the first series of 'Kingdom,' and we are very honored to be a part of the movie again," said vocalist Taka in a press statement. "We tried to reflect "the various conflicts going on in the world today and the modern society" in the song, while making it blend into the worldview of 'Kingdom.'"

Cat Burns — 'early twenties'

A love letter to her community and a deep dive into the intricacies of adulthood, Cat Burns presents her debut album, Early Twenties. Accompanying the album is a captivating short film directed by Libby Burke Wilde. The film tells the individual narratives of each character, touching on themes of mental health, relationships, and personal identity, mirroring the album's essence.

With this well-rounded creative project, Burns showcases her full artistic prowess, making these releases a testament to her pioneering creative vision.

Uncle Kracker — 'Coffee & Beer'

Making a triumphant return to music after 12 years, Uncle Kracker breaks down the boundaries between genres once again with his latest album, Coffee & Beer. The 13-track album intertwines country, pop, and rock, offering a musical journey that ranges from high-spirited anthems to laid-back, mellow tracks.

"I wanted to give my fans a soundtrack to summer and what's better than the balance of first coffee…then beer? Coffee & Beer is going to be a fun one. Cheers," Uncle Kracker said in a press statement.

Meridian Brothers — 'Mi Latinoamérica Sufre'

Drawing inspiration from the golden era of '70s Congolese rumba, Ghanaian highlife, and Nigerian afrobeat, the Meridian Brothers unveil Mi Latinoamérica Sufre. This concept album integrates the electric guitar into tropical Latin music in an innovative fashion. The album showcases a dynamic tapestry of sounds, blending cumbia, champeta, soukous, Brazilian tropicalia, and psychedelic rock, making it an exciting sonic journey.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'