Photo: Austin Lord

Peter Frampton Band

news

Peter Frampton On Whether He'll Perform Live Again, Hanging With George Harrison & David Bowie And New Album 'Frampton Forgets the Words'

At 70 years old, Peter Frampton is happy, creative and generally healthy. But whether he'll finish his thwarted farewell tour depends on when the world reopens—and if he can keep his degenerative muscle condition at bay

A year and a half ago, Peter Frampton may have played his final concert. Standing alone at the Concord Pavilion, just north of San Francisco, on October 12, 2019, he didn't want to follow his band offstage at the end of his performance. He didn't want to stop.

"I had to wait until the crowd would calm down," Frampton tells GRAMMY.com. "In the end, I had to shut them up to say 'Thank you.' And I never said goodbye. I just said, 'I'm not going to say goodbye.'" Despite the fact the 70-year-old is creatively active and taking care of himself, the time will come when he has to say goodbye to touring. When? His inclusion body myositis, or IBM, will dictate that.

The degenerative muscle condition, which has no cure, may one day claim his guitar mastery. And at that point, Frampton says, he will stop. But if it's cruel that the COVID-19 pandemic potentially robbed him of his final viable year as a live performer, Frampton doesn't carry any detectable resentment about it. The one-time GRAMMY winner and five-time nominee is too busy playing guitar—and every time he picks up the instrument, he says, it feels like the last time.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/8gOob5hoOEI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

That bittersweet parting between a man and his lifelong communication tool colors the Peter Frampton Band's latest instrumental album, Frampton Forgets the Words, which drops April 23 via UMe. (His last album 2007's Fingerprints, won a GRAMMY for Best Pop Instrumental Album; his cover of Soundgarden's "Black Hole Sun" won Best Rock Instrumental Performance.)

Frampton Forgets the Words is a grab-bag of 10 covers of rock songs that just plain move Frampton, and he imbues every lick and line of tunes by Radiohead ("Reckoner"), Roxy Music ("Avalon") Lenny Kravitz ("Are You Gonna Go My Way") and other legacy artists with deep feeling and panache.

GRAMMY.com gave Frampton a ring about the future of his touring career, why he chose these songs, and his relationships with David Bowie and George Harrison—both of whom he covered on this album. Check out Frampton Forgets the Words' version of Bowie's "Loving the Alien," which premieres exclusively above, and read on for the interview.

The pandemic interrupted your farewell tour, yeah?

Yes. We were lucky. I was so, so lucky that we decided to start it in May of '19 because we managed to get halfway through. We finished the U.S.-Canada portion in mid-October. And then, of course, by March, we were shut down. We were supposed to go to Europe in 2020, in May. Realistically, it was the right thing. We're all in the same boat, so it was definitely the right thing to do. But, yeah, it was disappointing.

Did you record Frampton Forgets the Words before or after COVID-19 hit?

Before. It was recorded before the finale tour. We did three, nay, four albums before coming off the road in 2018—again, in October-ish—with Steve Miller. Then, took nine or 10 days off, went straight into the studio and did the All Blues album and another blues album, which has yet to come out. Then, we took Christmas off and in early 2019, we did Forgets the Words.

And then, we started after that, all the way up to April sometime, we were working on my first new solo album since the last one.

Peter Frampton in 1973. Photo: George Wilkes/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Were you playing some of the Frampton Forgets the Words tunes during the farewell tour?

No, we were playing stuff off All Blues, but we were not playing anything off the instrumental record. Because it wasn't out yet, and also, that meant we could do some of the Fingerprints instrumentals, like "Black Hole Sun" and occasionally some of the other ones in there from that album.

This album feels very personal, in a sense. I remember reading a past interview where you said your playing has become more soulful over the past few years due to some of the physical issues you've been facing. It sounds like you're profoundly feeling every note of these songs.

I think it's a combination of things. I treasure being able to play so much, and of course, it's weighing on my mind that I do have my muscle disease clock—the IBM clock, I call it. Because I am slowly, slowly, slowly… but it's very slow.

I think it's a combination of having played so many notes over the years—I've chosen what not to play anymore [laughs]—and I feel like every time I pick the guitar up, it's like I'm playing for the last time. So, I put my heart and soul into it, especially on stage. Especially on the finale tour, because the audiences were different every night, but the feeling I got from every audience was exactly the same. It was a phenomenal feeling of them all putting their arms around me and saying, "It's going to be OK." I got chills saying that. But I did, I felt that, and I realized I've touched a lot of people and their lives.

It really brought it home to me, how much my music has meant to so many people. It was just a two-way "Thank you" the whole night, on every show. I have to say, every show. And at the end, I would be left on my own on the stage, the band would leave, and I had to wait until the crowd would calm down. In the end, I had to shut them up to say "Thank you."

They didn't want us to leave. And I never said goodbye. I just said, "I'm not going to say goodbye. I'm just waving." It was just phenomenal. The best experience of my whole career of touring.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//sfqucAJ3w1I' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

That's lovely, truly. I noticed while listening to Frampton Forgets the Words that even without lyrics, each song's intent came through loud and clear. Just your guitar "singing" them. Do you feel the emotions of "Isn't It a Pity" or "Reckoner" come through simply in the melodies and performances when you strip away the verbal element?

Well, I started as an instrumental player because of The Shadows, this incredible pre-Beatles instrumental band that was Cliff Richard's backup band as well. They had so many hits. You would call it "surf music," but we would call it The Shadows. So that's how I started—with very melodic stuff.

Let's home in on "Isn't It a Pity," a song of compassion and tender concern. Your instrumental version telegraphs those emotions even without George's words.

My guitar is another voice. It's like I sing with my voice and I play with another voice. It's always been the most expressive part of what I do, is play. So, when I chose these songs to do instrumental versions of, I chose them because of my capability, of what I thought I could do.

"Isn't It a Pity," I tried to sound like George's voice but in my voice, if you know what I'm saying. It was an emulation of what he was singing. Obviously, with an instrumental, you don't have the second verse with different words to keep peoples' attention. So you have to make it more interesting as it goes along, with the notes you choose.

So, that one is what I enjoyed doing the most. That one and also Roxy Music's "Avalon." I'll play my own trumpet here, even though I play guitar: Brian Ferry's voice on "Avalon" is like, "Is there something coming out?" It's so laid back and I wanted to be able to emulate not the sound of his voice, but the effect his voice had on the listener. I'm very, very proud of the sound and the playing, especially on the verses of "Avalon."

You're terrific at building drama, too. You may not be able to add a second verse, but you can add embellishments that up the ante.

You have to do that. Otherwise, it would be boring.

We're touching a lot of spheres in rock history with this tracklist. What's the common thread between these 10 tunes, beyond the simple fact that you love them?

It's something that these songs all stir emotion within me. Especially Radiohead and even "Dreamland," which is the Jaco Pastorius tribute. I couldn't do most of these songs because as a guitar player, I can't play as fast as he could play on bass!

But it's all a choice of notes. That's the common thread. If you compare "Dreamland" with [Alison Krauss’] "Maybe," which is the end track, it's about the melody. It's about that choice of notes over that chord sequence. And I think it rings true with all of them.

"Isn't It a Pity" has got that diminished kind of chord that George does on the second line, and that just sets it apart from every other song on All Things Must Pass. And it was the first one I heard when I went into the studio. They had already done that track when I sat down and started cutting tracks with them, with George.

I've never forgotten… well, first of all, it's my first time walking into Abbey Road. I'm not going on a tour; I'm going to play on an album with George Harrison and all these incredible players, you know? Ringo, Jim Gordon, Klaus Voormann, Billy Preston. It was just unbelievable. So, I've never forgotten that moment when I heard "Isn't It a Pity."

It's always been the one that just… again if I get goosebumps, you're in!

What was your relationship like with George?

I had a very, very good relationship with George. Apart from meeting him the same day as he asked me to play on the Doris Troy album, and then asked me back for All Things Must Pass, my wife and I—Mary, at the time—would go down to Friar Park, where they lived, and spend time on the weekends with George and Pattie. It became kind of a thing. He was a dear friend and I miss him terribly.

We've got David Bowie in there, with "Loving the Alien." Did you know him as well?

We went to school together. I met David when I was 12 or 13 [years old.] My father was his art teacher in high school for three years. He became—as well as my friend—almost closer to my dad because my dad was the head of the art department and it was every form of visual art known to man, from typography to fine art to you-name-it. History of architecture, the whole bit.

My dad obviously taught everybody, but when there was a student—in this case, a couple; there was George Underwood, who did the Ziggy Stardust cover as well as many others for David, who's a fantastic fine artist, a painter. I have some of his work here. He was Dave's best friend for life.

So, it was the two of them I met. At one point, my dad said, "Well, you boys all play these guitars and this rock 'n' roll music. Why don't you bring your guitars to school, and I'll stick 'em in my office, and you can play them at lunchtime? So we did, and David became sort of more of a family friend.

When we did the introduction to the Glass Spider tour in London, my parents came up and afterward, there was a press conference and we played about four or five numbers. So afterward, my parents were backstage. And I'm talking to Mom and I'm saying, "Where's Dad?" She's saying, "Oh, I don't know. He went off with Dave somewhere!" They would just disappear off together.

When I lost my dad, Dave was the first person to call. That gives you some idea.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//mX75M_ONZgU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Such intimate connections! I also wanted to touch on Radiohead, since they're the most contemporary act of the bunch. What's your relationship with those guys and/or their music? I'm not sure if you know them personally.

No, I don't know them. But from afar, I'm amazed by that band. It's one of the most inventive bands ever, I think, and they keep reinventing themselves with every album, every piece. It's something so special; it's very unique. I mean, every band is unique in some way, but Radiohead are way ahead of their time, I think, which is wonderful.

I can learn so much from them just listening to the way [Thom Yorke] sings, plays, the way they all write, the basic chord sequence and the track and the riff. You know, I delve in there. It's a lesson for a musician. It's a really big lesson listening to any one of their songs.

Let's say, best case scenario, venues start to open this summer. Are you going to try to finish up your farewell tour?

This is where I have to give you the realistic chat. Not you—I have to be realistic because we all have one clock. Well, we've got two clocks right now, worldwide, that we live with. One is our life-clock and one is the COVID clock.

The COVID clock is stopping everybody from being around each other, for good reason, right now, obviously. And the more we stay away from each other, unfortunately, at this time, the better it is. But I have a third clock, which is my IBM—inclusion body myositis—clock. Slowly but surely, unfortunately, I'm losing strength in my hands, my arms and my legs.

It's specific muscles it hits. It picks and chooses the muscles and there's no rhyme or reason for it. They don't know; there's no cure. If it takes another year before we can reschedule any dates, I will have to be realistic to see if my hands work or my legs will keep me up.

That's what I have to deal with, and I think there's a certain level of playing where I won't perform anymore. If I can't play certain things the way I want to—I don't want to be that person to go out there and people feel bad for me because I don't play as good but I am Peter Frampton. That's not going to happen.

If I go out having played my last show [near] San Francisco on October 12, 2019, if that's my last show, then so be it. But obviously, I am hoping more than anybody else that within a year—or if it is a year; I'm imagining it's going to be at least a year—if things aren't doing good, then that will be it for me, unfortunately.

In the meantime, it seems like you're feeling good and you're creatively percolating. What are you listening to lately? If you were to make another instrumental record, what might be on it, based on what you're checking out these days?

Oh, gosh. I can't answer that question. That's a whole thought process I'd need, like, a month for!

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

list

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

This week in 1964, the Beatles changed the world with their iconic debut film, and its fresh, exuberant soundtrack. If you like music videos, folk-rock and the song "Layla," thank 'A Hard Day's Night.'

Throughout his ongoing Got Back tour, Paul McCartney has reliably opened with "Can't Buy Me Love."

It's not the Beatles' deepest song, nor their most beloved hit — though a hit it was. But its zippy, rollicking exuberance still shines brightly; like the rest of the oldies on his setlist, the 82-year-old launches into it in its original key. For two minutes and change, we're plunged back into 1964 — and all the humor, melody, friendship and fun the Beatles bestowed with A Hard Day's Night.

This week in 1964 — at the zenith of Beatlemania, after their seismic appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" — the planet received Richard Lester's silly, surreal and innovative film of that name. Days after, its classic soundtrack dropped — a volley of uber-catchy bangers and philosophical ballads, and the only Beatles LP to solely feature Lennon-McCartney songs.

As with almost everything Beatles, the impact of the film and album have been etched in stone. But considering the breadth of pop culture history in its wake, Fab disciples can always use a reminder. Here are six things that wouldn't be the same without A Hard Day's Night.

All Music Videos, Forever

Right from that starting gun of an opening chord, A Hard Day's Night's camerawork alone — black and white, inspired by French New Wave and British kitchen sink dramas — pioneers everything from British spy thrillers to "The Monkees."

Across the film's 87 minutes, you're viscerally dragged into the action; you tumble through the cityscapes right along with John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Not to mention the entire music video revolution; techniques we think of as stock were brand-new here.

According to Roger Ebert: "Today when we watch TV and see quick cutting, hand-held cameras, interviews conducted on the run with moving targets, quickly intercut snatches of dialogue, music under documentary action and all the other trademarks of the modern style, we are looking at the children of A Hard Day's Night."

Emergent Folk-Rock

George Harrison's 12-string Rickenbacker didn't just lend itself to a jangly undercurrent on the A Hard Day's Night songs; the shots of Harrison playing it galvanized Roger McGuinn to pick up the futuristic instrument — and via the Byrds, give the folk canon a welcome jolt of electricity.

Entire reams of alternative rock, post-punk, power pop, indie rock, and more would follow — and if any of those mean anything to you, partly thank Lester for casting a spotlight on that Rick.

The Ultimate Love Triangle Jam

From the Byrds' "Triad" to Leonard Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat," music history is replete with odes to love triangles.

But none are as desperate, as mannish, as garment-rending, as Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla," where Eric Clapton lays bare his affections for his friend Harrison's wife, Pattie Boyd. Where did Harrison meet her? Why, on the set of A Hard Day's Night, where she was cast as a schoolgirl.

Debates, Debates, Debates

Say, what is that famous, clamorous opening chord of A Hard Day's Night's title track? Turns out YouTube's still trying to suss that one out.

"It is F with a G on top, but you'll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story," Harrison told an online chat in 2001 — the last year of his life.

A Certain Strain Of Loopy Humor

No wonder Harrison got in with Monty Python later in life: the effortlessly witty lads were born to play these roles — mostly a tumble of non sequiturs, one-liners and daffy retorts. (They were all brought up on the Goons, after all.) When A Hard Day's Night codified their Liverpudlian slant on everything, everyone from the Pythons to Tim and Eric received their blueprint.

The Legitimacy Of The Rock Flick

What did rock 'n' roll contribute to the film canon before the Beatles? A stream of lightweight Elvis flicks? Granted, the Beatles would churn out a few headscratchers in its wake — Magical Mystery Tour, anyone? — but A Hard Day's Night remains a game-changer for guitar boys on screen.

The best part? The Beatles would go on to change the game again, and again, and again, in so many ways. Don't say they didn't warn you — as you revisit the iconic A Hard Day's Night.

Explore The World Of The Beatles

.webp)

5 Reasons John Lennon's 'Mind Games' Is Worth Another Shot

'A Hard Day's Night' Turns 60: 6 Things You Can Thank The Beatles Film & Soundtrack For

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

feature

On This Day In Music: 2 Live Crew's 'As Nasty As They Wanna Be' Becomes First Album Declared Legally Obscene, Anticipates First Amendment Cases

Known for their raunchy take on hip-hop, 2 Live Crew made history when 'As Nasty As They Wanna Be' was declared legally obscene. Thirty-four years later, here's how they fought back and turned their battle into a landmark First Amendment case.

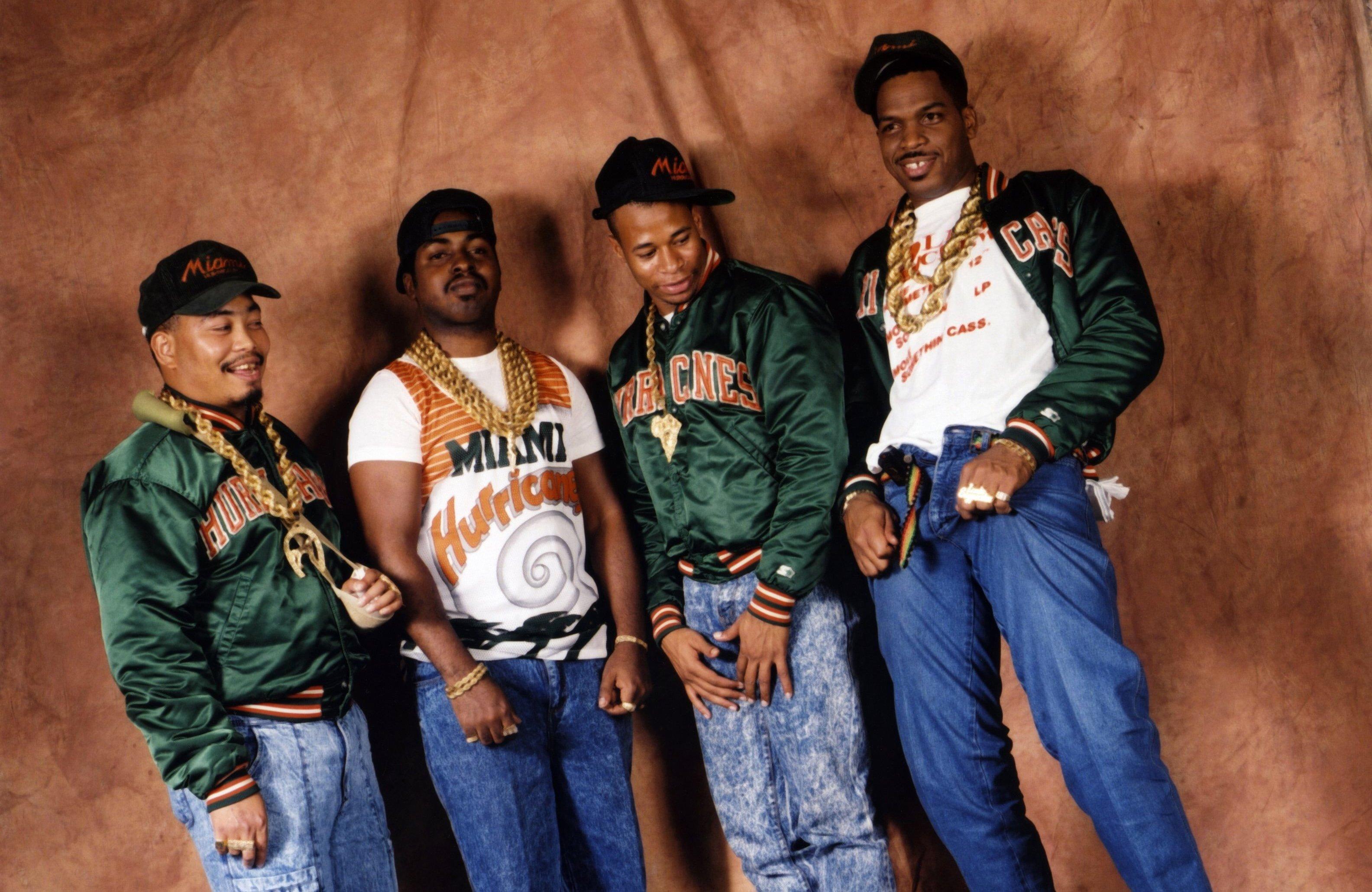

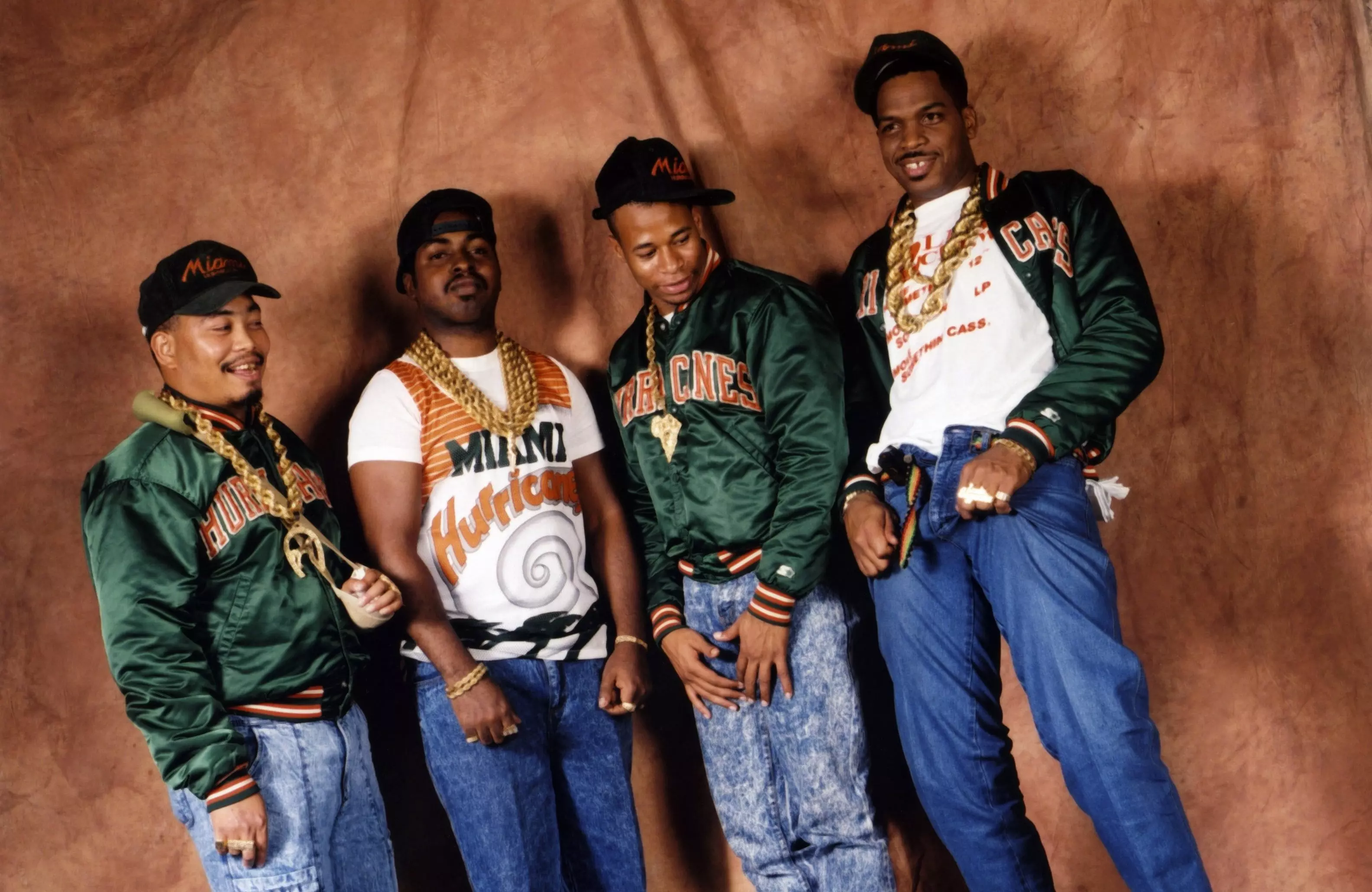

When 2 Live Crew released their third studio album, they never imagined it would lead to a mammoth of legal entanglements. In 1989, the Miami-based hip-hop group dropped As Nasty As They Wanna Be, a title that held true throughout the ensuing legal battle.

In an effort to put their music on the map and distinguish themselves in the rap game, amidst one of hip-hops finest eras, the album featured sexually explicit themes and graphic content, leading to extreme popularity within pop culture. However, this widespread attention wasn’t all in a good light.

In Broward County, Florida, Sheriff Nick Navarro took a stand against the group, endeavoring to prevent local record store owners from selling the provocative album. In defiance of this censorship, 2 Live Crew filed a lawsuit in federal court, seeking legal recourse to halt the sheriff’s crackdown, prevent restrictions on album sales and legally defend their work as non-obscene.

Through the court's ruling, they deemed the work legally obscene and prohibited retailers from selling the album in Florida’s Broward, Dade, and Palm Beach counties.

Following the ruling, Florida record store owner Charles Freeman was arrested for selling As Nasty As They Wanna Be and three 2 Live Crew members were also arrested for performing their explicit music live at a nightclub in Hollywood, Florida.

Challenging the initial ruling with tenacity, the group’s record label, Luke Records, founded by 2 Live Crew member Luther Campbell, brought the case in front of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

In this legal battle, the Eleventh Circuit Court applied the Miller Test, a benchmark for obscenity set by the United States Supreme Court’s test in the 1973 Miller v. California case. To meet the standards of the test, the work being challenged must appeal to a prurient, or shameful interest in sex, depict sexual materials in a patently offensive way, and lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. Luke Records called four experts in their fields to the stand, while Navarro failed to provide concrete evidence that the album met the standards outlined by the Miller Test.

In the Court of Appeals, it was found that the album did not meet the standards of obscenity that were set forth in the Miller Test. Since As Nasty As They Wanna Be was a creative work of music, the court ruled that the album had artistic value and thus did not meet all the standards to be deemed as obscene.

"I’ve been listening to the album by 2 Live Crew. It’s not the best album that’s ever been made, but when I heard they banned it, I went out and bought it," said David Bowie during his 1990 tour in Philadelphia, stopping in the middle of his performance to defend the group. "Freedom of thought, freedom of speech — it’s one of the most important things we have."

Last week, 2 Live Crew member Brother Marquis passed away, prompting Campbell to take to Twitter and honor his friend and fellow member, stating, "We took on so many fights for the culture, made great music together, something I will never forget."

To this day, the case against 2 Live Crew serves as a legal standard for First Amendment Rights, upholding the boundaries between censorship and freedom of speech within music.

"They really set a legal precedent for hip-hop artists today to be able to create in the way that they choose to," says Kiana Fitzgerald in her book "Ode to Hip-Hop." In the book, she also cites contemporary examples of hip-hop artists who openly speak about sex in their discography, like Megan Thee Stallion, Cardi B, Lil Wayne, and others.

Through 2 Live Crew’s legal fight, they paved the way as trailblazers for hip-hop artists to be As Nasty As They Wanna Be — without facing speech-smothering legal repercussions.

Explore More History-Making Moments In Music

On This Day In Music: Spice Girls Release "Wannabe," Their Iconic Debut Single

On This Day In Music: Michael Jackson Passes Away In Los Angeles At Age 50

On This Day In Music: Mariah Carey Releases Her Self-Titled Debut Album

On This Day In Music: "American Idol" Premieres On Fox Network

On This Day In Music: 2 Live Crew's 'As Nasty As They Wanna Be' Becomes First Album Declared Legally Obscene, Anticipates First Amendment Cases

Photo: Christopher Caldwell

news

Blues Music Awards 2024 and Blues Hall Of Fame Inductee Ceremony Honor the Past, Present, & Future Of The Blues

The Blues Music Awards kicked off several days of events honoring the genre's legacy, which included the Blues Hall of Fame Inductee ceremony and the opening of an innovative new exhibit at the Blues Hall of Fame featuring a hologram of Taj Mahal.

It was a big week for music in Memphis. The 45th annual Blues Music Awards, a top honor in the genre, were handed out on Thursday, May 9, in Memphis, Tenn. in a ceremony sponsored by the Recording Academy. The awards were the capstone to several days of blues-related events, including the annual Blues Hall of Fame induction ceremony the day before.

An audience of approximately 1,000 — including industry professionals, fans, and some of the genre's biggest artists — packed the grand main exhibit hall of the recently renovated Renasant Convention Center for the BMAs banquet, produced by the Memphis-based Blues Foundation. With 25 awards and more than a dozen performances, the awards show, hosted by broadcast veteran Tavis Smiley, often felt more like a homecoming than an industry event.

Read below for four key takeaways from this year's Blues Music Awards and Blue Hall of Fame Ceremony.

Mississippi's Blues Roots Remain Strong

Located right next to Memphis, Mississippi is home to one of the country's four GRAMMY Museums and is widely regarded as one of the birthplaces — if not the birthplace — of the blues. The state has nurtured some of the genre's greatest talents, including Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and B.B. King. The Magnolia State's deep connection to the blues was evident during the awards, with Mississippi mainstays and GRAMMY winners Bobby Rush and Christone "Kingfish" Ingram among the top winners.

Despite a 65-year age difference, Rush and Ingram share a deep devotion to the blues. At 90 years old, Rush, an incredibly spry chitlin' circuit road warrior who has re-emerged in recent years as perhaps one the blues' biggest stars, won Best Soul Blues Album for All My Love for You and his second B.B. King Entertainer of the Year award. Ingram, only 25 years old and already a GRAMMY winner for Best Contemporary Blues Album in 2022, was the night's top winner, taking home four awards: Album of the Year and Contemporary Blues Album of the Year for Live in London, Contemporary Blues Male Artist, and Instrumentalist-Guitar.

Other multiple award winners included another artist originally from Mississippi, 79-year-old Chicago guitarist John Primer, who won Traditional Blues Male Artist and Traditional Blues Album for Teardrops for Magic Slim, and Texas' Ruthie Foster, who captured top vocalist honors and won Song of the Year for "What Kind Of Fool," co-written with Hadden Sayers and Scottie Miller.

The Blues Need To Be Seen To Be Heard

Though the BMAs largely honor recorded works, the show itself emphasized that the blues are a genre best experienced live. The ceremony, which ran about four hours (historically on the shorter side for this event), was packed full of performances, most running longer than your typical awards show slots.

Highlights included the opening set by emerging artist nominee Candice Ivory, who performed selections from her BMA-nominated album When the Levee Breaks: The Music of Memphis Minnie, backed by keyboardist Ben Levin and guitarist William Lee Ellis, who also played songs from his album Ghost Hymns, a nominee for Best Acoustic Album.

Another Mississippi artist, powerhouse bandleader Castro Coleman, known as Mr. Sipp, who has one GRAMMY nomination and an appearance on a GRAMMY-winning Count Basie Orchestra album, brought the crowd to their feet early with his gospel-fueled segment. To cement his Best Guitarist win, Ingram delivered a blistering performance with his band, wading into the audience for one of his beautifully precise, soaring solos.

There was so much music to be heard that it spilled out into the streets. Most nights following BMA-related events, fans and fellow artists could be found in the clubs on Beale Street, the famous Home of the Blues, for showcases and impromptu jam sessions. These were highlighted by the 10th annual Down In the Basement fundraiser for the Blues Foundation on Wednesday. Organized and hosted by Big Llou Johnson, a blues musician and host of Sirius XM's B.B. King's Bluesville channel, the show featured appearances by Mr. Sipp, GRAMMY nominees Southern Avenue, and more.

Honoring The Blues' Past

Among the other events that made up BMA week was the Blues Hall of Fame Induction ceremony, held on May 8 at Memphis' Cannon Center for the Performing Arts before a crowd of about 200, including past inductees Bobby Rush and Taj Mahal. Hosted by artists Gaye Adegbalola (Saffire — the Uppity Blues Women), GRAMMY winner Dom Flemons (Carolina Chocolate Drops), and veteran blues radio deejay Bill Wax, the observance saw the induction of seven artists, five blues singles, one album, a book, and a blues academic into the Hall of Fame.

Highlights from the evening included Alligator Records head Bruce Iglauer's humor-filled induction of Chicago house stompers Lil' Ed & the Blues Imperials in the performers category; the heartfelt introduction of the late folk singer Odetta by her friend Maria Muldaur and the emotional acceptance by Odetta's daughter, Michelle Esrick; and former National Endowment for the Humanities chairman William R. Ferris, inducted as a non-performer, delivering a circuitous-but-engrossing recounting of his life documenting blues music and culture.

Bringing The Blues To Life

Taj Mahal stands in front of the exhibit featuring his own hologram. | Photo: Kimberly Horton

One of the non-award related highlights of the week was the opening of a new exhibit at the Blues Foundation's Blues Hall of Fame, also on May 8, which introduced a high-tech element to the down-home genre. Musician Taj Mahal was on hand the day before for the unveiling of a cutting-edge AI-powered hologram of himself that acts as a virtual tour guide for the Half of Fame, allowing visitors to interact with the blues great.

This hologram, only the second exhibit of its kind in America (the first is in the Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame in Boston), uses Holobox, a new technology from Holoconnects, to render a life-like image that can answer questions, talk about exhibits, and play instruments. Taj Mahal, who had to sit and talk for several hours for the technology to scan his likeness and voice, is the first artist to receive the virtual treatment from the Blues Foundation. Bobby Rush and Keb' Mo' are expected to be added later.

Explore the full list of 2024 BMA winners below to celebrate the artists keeping the blues alive and discover who took home the top honors this year.

2024 BMA Winners

B.B. King Entertainer of the Year

Bobby Rush

Album of the Year

Live In London, Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Band of the Year

Nick Moss Band

Song of the Year

"What Kind Of Fool," written by Ruthie Foster, Hadden Sayers & Scottie Miller

Best Emerging Artist Album

The Right Man, D.K. Harrell

Acoustic Blues Album

Raw Blues 1, Doug MacLeod

Blues Rock Album

Blood Brothers, Mike Zito/ Albert Castiglia

Contemporary Blues Album

Live In London, Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Soul Blues Album

All My Love For You, Bobby Rush

Traditional Blues Album

Teardrops for Magic Slim, John Primer

Acoustic Blues Artist

Keb' Mo'

Blues Rock Artist

Mike Zito

Contemporary Blues Female Artist

Danielle Nicole

Contemporary Blues Male Artist

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Soul Blues Female Artist

Annika Chambers

Soul Blues Male Artist

John Nemeth

Traditional Blues Female Artist (Koko Taylor Award)

Sue Foley

Traditional Blues Male Artist

John Primer

Instrumentalist – Bass

Bob Stroger

Instrumentalist – Drums

Kenny "Beedy Eyes" Smith

Instrumentalist – Guitarist

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Instrumentalist – Harmonica

Jason Ricci

Instrumentalist – Horn

Vanessa Collier

Instrumentalist – Piano (Pinetop Perkins Award)

Kenny "Blues Boss" Wayne

Instrumentalist – Vocals

Ruthie Foster

Washington D.C. Chapter Dinner & Conversation Answers "Can We Have Rhythm Without the Blues?"

Photo: Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd

list

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

More than five decades after its 1970 release, Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 'Let it Be' film is restored and re-released on Disney+. With a little help from the director himself, here are some less-trodden tidbits from this much-debated film and its album era.

What is about the Beatles' Let it Be sessions that continues to bedevil diehards?

Even after their aperture was tremendously widened with Get Back — Peter Jackson's three-part, almost eight hour, 2021 doc — something's always been missing. Because it was meant as a corrective to a film that, well, most of us haven't seen in a long time — if at all.

That's Let it Be, the original 1970 documentary on those contested, pivotal, hot-and-cold sessions, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Much of the calcified lore around the Beatles' last stand comes not from the film itself, but what we think is in the film.

Let it Be does contain a couple of emotionally charged moments between maturing Beatles. The most famous one: George Harrison getting snippy with Paul McCartney over a guitar part, which might just be the most blown-out-of-proportion squabble in rock history.

But superfans smelled blood in the water: the film had to be a locus for the Beatles' untimely demise. To which the film's director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, might say: did we see the same movie?

"Looking back from history's vantage point, it seems like everybody drank the bad batch of Kool-Aid," he tells GRAMMY.com. Lindsay-Hogg had just appeared at an NYC screening, and seemed as surprised by it as the fans: "Because the opinion that was first formed about the movie, you could not form on the actual movie we saw the other night."

He's correct. If you saw Get Back, Lindsay-Hogg is the babyfaced, cigar-puffing auteur seen throughout; today, at 84, his original vision has been reclaimed. On May 8, Disney+ unveiled a restored and refreshed version of the Let it Be film — a historical counterweight to Get Back. Temperamentally, though, it's right on the same wavelength, which is bound to surprise some Fabs disciples.

With the benefit of Peter Jackson's sound-polishing magic and Giles Martin's inspired remixes of performances, Let it Be offers a quieter, more muted, more atmospheric take on these sessions. (Think fewer goofy antics, and more tight, lingering shots of four of rock's most evocative faces.)

As you absorb the long-on-ice Let it Be, here are some lesser-known facts about this film, and the era of the Beatles it captures — with a little help from Lindsay-Hogg himself.

The Beatles Were Happy With The Let It Be Film

After Lindsay-Hogg showed the Beatles the final rough cut, he says they all went out to a jovial meal and drinks: "Nice food, collegial, pleasant, witty conversation, nice wine."

Afterward, they went downstairs to a discotheque for nightcaps. "Paul said he thought Let it Be was good. We'd all done a good job," Lindsay-Hogg remembers. "And Ringo and [wife] Maureen were jiving to the music until two in the morning."

"They had a really, really good time," he adds. "And you can see like [in the film], on their faces, their interactions — it was like it always was."

About "That" Fight: Neither Paul Nor George Made A Big Deal

At this point, Beatles fanatics can recite this Harrison-in-a-snit quote to McCartney: "I'll play, you know, whatever you want me to play, or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you… I'll do it." (Yes, that's widely viewed among fans as a tremendous deal.)

If this was such a fissure, why did McCartney and Harrison allow it in the film? After all, they had say in the final cut, like the other Beatles.

"Nothing was going to be in the picture that they didn't want," Lindsay-Hogg asserts. "They never commented on that. They took that exchange as like many other exchanges they'd had over the years… but, of course, since they'd broken up a month before [the film's release], everyone was looking for little bits of sharp metal on the sand to think why they'd broken up."

About Ringo's "Not A Lot Of Joy" Comment…

Recently, Ringo Starr opined that there was "not a lot of joy" in the Let it Be film; Lindsay-Hogg says Starr framed it to him as "no joy."

Of course, that's Starr's prerogative. But it's not quite borne out by what we see — especially that merry scene where he and Harrison work out an early draft of Abbey Road's "Octopus's Garden."

"And Ringo's a combination of so pleased to be working on the song, pleased to be working with his friend, glad for the input," Lindsay-Hogg says. "He's a wonderful guy. I mean, he can think what he wants and I will always have greater affection for him.

"Let's see if he changes his mind by the time he's 100," he added mirthfully.

Lindsay-Hogg Thought It'd Never Be Released Again

"I went through many years of thinking, It's not going to come out," Lindsay-Hogg says. In this regard, he characterizes 25 or 30 years of his life as "solitary confinement," although he was "pushing for it, and educating for it."

"Then, suddenly, the sun comes out" — which may be thanks to Peter Jackson, and renewed interest via Get Back. "And someone opens the cell door, and Let it Be walks out."

Nobody Asked Him What The Sessions Were Like

All four Beatles, and many of their associates, have spoken their piece on Let it Be sessions — and journalists, authors, documentarians, and fans all have their own slant on them.

But what was this time like from Lindsay-Hogg's perspective? Incredibly, nobody ever thought to check. "You asked the one question which no one has asked," he says. "No one."

So, give us the vibe check. Were the Let it Be sessions ever remotely as tense as they've been described, since man landed on the moon? And to that, Lindsay-Hogg's response is a chuckle, and a resounding, "No, no, no."