Photo: Assunta Opahle

feature

Ian Anderson Of Jethro Tull’s Themes & Inspirations, From 'RökFlöte' Backward

Jethro Tull's new album 'RökFlöte' is deeply influenced by old Norse paganism. And as per Ian Anderson's bank of lyrical concepts, it only scratches the surface.

Ian Anderson was finishing up an interview about the first Jethro Tull album in almost two decades, 2022’s The Zealot Gene, when he offered GRAMMY.com some tantalizing news: the next one would arrive sooner rather than later.

"At 9 o'clock on the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse," Anderson said two weeks before the end of 2021. "Should she decide to visit — hopefully, by 10 o'clock, I'll have the beginnings of some kind of flicker of an idea."

Where might Anderson, a voracious reader with a sweeping purview and a learned, gentlemanly air, go from there?

Fast forward to today, and we have the result: RökFlöte, which arrived April 21 and is based on "the characters and roles of some of the princip[al] gods of the old Norse paganism."

The GRAMMY-winning prog-rock heroes’ catalog has always been flecked with similar mythology, especially on 1977's fantastical, bucolic Songs From the Wood. But never had Anderson dedicated an entire album to this specific system of concepts.

RökFlöte’s opener, "Voluspo," is titled after the most famous poem in the Poetic Edda, which dates back centuries. Lead single "Ginnungagap" refers to the bottomless abyss that encompassed all things prior to the creation of the cosmos. "Ithavoll" is the meeting place of the gods.

This sheer depth of reference is not new for Anderson and company. A band less cited for their musical and philosophical depth than mined for cheap codpiece and Anchorman jokes, Jethro Tull contain multitudes just beneath the surface.

Take a stroll through the band's discography, and you'll find Anderson doesn't linger on one topic for long — and often addresses many concepts within the same album, or even song. Even Tull's most straightforward hits often contain richer meaning than what immediately meets the ear.

To celebrate the release of RökFlöte, here's a by-no-means-comprehensive breakdown of the poles Anderson and crew have tended to touch on throughout the band' almost 60-year career.

Love (With Some Caveats)

"I am a descriptive writer," Anderson wrote in the preface to his career-spanning compendium of lyrics, Silent Singing. "Not so often a storyteller, and almost never a heart-on-sleeve love-rat. Social documentary that you can hum along to."

True, this applies to the lion's share of his songs. But there are a couple of major exceptions — perhaps ones that prove the rule.

Take "Wond'ring Aloud," his gorgeous acoustic ballad on 1971's Aqualung that clocks in at less than two minutes. If there's any kind of social commentary or obscure meaning in "Wond'ring Aloud," it's difficult to tease out. Rather, the tune unfurls a quiet, domestic tableau of romantic bliss:

"Last night sipped the sunset/ My hand in her hair," he sings. "We are our own saviors as we start/ Both our hearts beating life into each other." The aroma of breakfast wafts through the kitchen; he considers their years ahead. Then, the unforgettable closing line: "And it's only the giving that makes you what you are."

Flash forward to "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All," another gobsmacking acoustic-with-strings centerpiece, from 1975's Minstrel in the Gallery.

Online chatter seems to suggest that the image of "one white duck on your wall" refers to a domestic split. Whatever the case, the darkly romantic song is suggestive of packing and leaving: "There's a haze on the skyline to wish me on my way/ There's a note on the telephone, some roses on a tray." From there, the song unfurls into a litany of images, commensurately puzzling and evocative — and full of arcane British-isms.

Like every other arena of life represented in Jethro Tull songs, romance comes with bottomless shades and nuances — and Anderson's seemingly attuned to the full spectrum.

Religion (As A Nonbeliever)

Jethro Tull classics that address faith, like Aqualung's "My God," "Hymn 43" and "Wind Up," excoriate religious corruption and dogma — to the degree that Anderson comes across as defensive of God.

"It's about turning God into a vehicle for personal power and the glitz and paraphernalia that sometimes surrounds religion," Anderson wrote of "My God" in 2019's oral history of the band, The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "It's actually quite pro-God in asking: 'People what have you done/ Locked him in his golden cage?'"

In "Wind Up," he rails: "I don't believe you/ You have the whole damn thing all wrong/ He's not the kind you have to wind up on Sundays." But it's crucial to stress that Anderson is decidedly not a man of faith.

Read More: Jethro Tull's Aqualung At 50: Ian Anderson On How Whimsy, Inquiry & Religious Skepticism Forged The Progressive Rock Classic

"I've learned to describe myself as somewhere between a pantheist and a deist," he wrote. "I'm not a Christian, but I like to do things for the church. I've always believed there are certain aspects of our society that, while anachronistic, are still worth preserving."

In an Olde English font in the Aqualung sleeve, Anderson printed a facsimile of Genesis 1:1: "In the beginning Man created God; and in the image of Man created He him."

Of the religious commentary scattered throughout Tull's discography, none seem to summarize Anderson's views like the above.

Nature (The Non-Human Kind)

Jethro Tull's so-called "folk trilogy" in the late 1970s — Songs From the Wood, Heavy Horses, and Stormwatch — address the natural world from three different angles.

Songs From the Wood is drenched in the atmosphere of the English countryside, where “fairytale creatures, ley lines, naughty equestriennes and the pre-Christian era old gods all came to call," Anderson writes in Silent Singing. The jangling "Jack-in-the-Green," about a raggy character somewhere between a hobbit and the wizard Radagast, is one irresistible highlight.

The majestic Heavy Horses is something of a song cycle about animal life. The serrating opener "...And the Mouse Police Never Sleeps" nails cats, with evocative lines including "Claws that rake a furrow red/ License to mutilate" and "Windy rooftop weathercock/ Warm-blooded night on a cold tile." From there: dogs, moths, weathervanes, the passing of equine generations.

While Stormwatch's compartmentalization as a "folk album" is somewhat suspect — only "Dun Ringill" really fits the mold — it's spiritually connected to Songs From the Wood and Heavy Horses on that conceptual front.

Anderson had addressed climate change before, as on "Skating Away on the Thin Ice of a New Day" on 1974's War Child. ("Predicated on the then-mistaken belief, in popular science circles, that we were headed toward another ice age," Anderson writes in Silent Singing.)

The gloomy Stormwatch takes that theme all the way home; the 1979 album draws its power from the weather and the ocean — as well as paranoia about humanity's bludgeoning impact on it.

As jabs at Exxon and their ilk go, "North Sea Oil" is up there with Neil Young's "Vampire Blues." The heavenward "Orion" is an awestruck gaze at the celestial panorama. And "Dun Ringill" warns "The weather's on the change/ Ice clouds invading and pressure forming."

Nature (The Human Kind)

Anderson may write his songs like a documentarian, but he’s arguably at his most powerful when writes from the human side of the equation.

Their barreling hit “Locomotive Breath,” from Aqualung, is about runaway population growth, through the lens of an “all-time loser” on a brakeless train, “headlong to his death.”

Thirteen tracks into Tull's 1972 odds-and-ends album Living in the Past is their deep cut to end all deep cuts: "Wond'ring Again." A sequel to "Wond'ring Aloud," it's about as angry and voluble as the band ever got.

"The excrement bubbles, this century's slime decays/ And the brainwashing government's lackeys would have us say/ It's under control and we'll soon be on our way/ To a grand year for babies and quiz panel games," goes just one of its dizzying lines.

But Anderson’s perspective isn’t always from a 50,000-foot view. In other tunes, he cuts to the chase regarding what makes humanity tick.

Read More: Ian Anderson On The Historical Threads Of Fanaticism, Playing Ageless Instruments & Jethro Tull's New Album The Zealot Gene

A goof on what Anderson perceived as bloated concept albums of the day, the narrative of 1972's one-song album Thick as a Brick flows in all directions. Yet the opening salvo, titled "Ready Don't Mind" on later editions, is especially incisive in its needling of small-minded biases.

"I may make you feel, but I can't make you think," Anderson declares amid the backdrop of "the sandcastle virtues… all swept away/In the tidal destruction, the moral melee."

On "Aqualung," Tull's classic portrait of a seedy, streetbound derelict, Anderson zooms in on how the straights perceive this loathsome character.

"[It's] more in terms of our reaction to the homeless," Anderson explained to GRAMMY.com in 2021. "I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel — compassion, fear, embarrassment. It's a very mixed and contradictory set of emotions."

Anderson’s reflections on human nature and the social order are not always that heavy; 1976's underrated Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! explores "the cyclical nature of fashion, music and youth culture" through the lens of a hapless, aging protagonist, trapped in the mire of his youthful interests.

The American rocker in "Said She Was a Dancer" from 1987's Crest of a Knave is similarly over-the-hill, as he flirts with a disinterested Muscovite. What a clash between "Eastern steel and Western gold": "You've seen me in your magazines, or maybe on state television," he complains. "I'm your Pepsi-Cola, but you won't take me out the can."

From here, you can open Silent Singing and head in any direction — horny Tull ("Kissing Willie," "Roll Yer Own"), tech-curious Tull ("Dot Com"), and even odes to household objects ("Wicked Windows," about eyeglasses.)

If you're already a Tull fan, chances are a dozen more examples of these umbrella concepts have already popped into your head. If you're a newbie, you've stumbled on one of the most eclectic, intelligent, criminally misunderstood rock bands of all time. Cheerio!

Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From This Was To The Zealot Gene

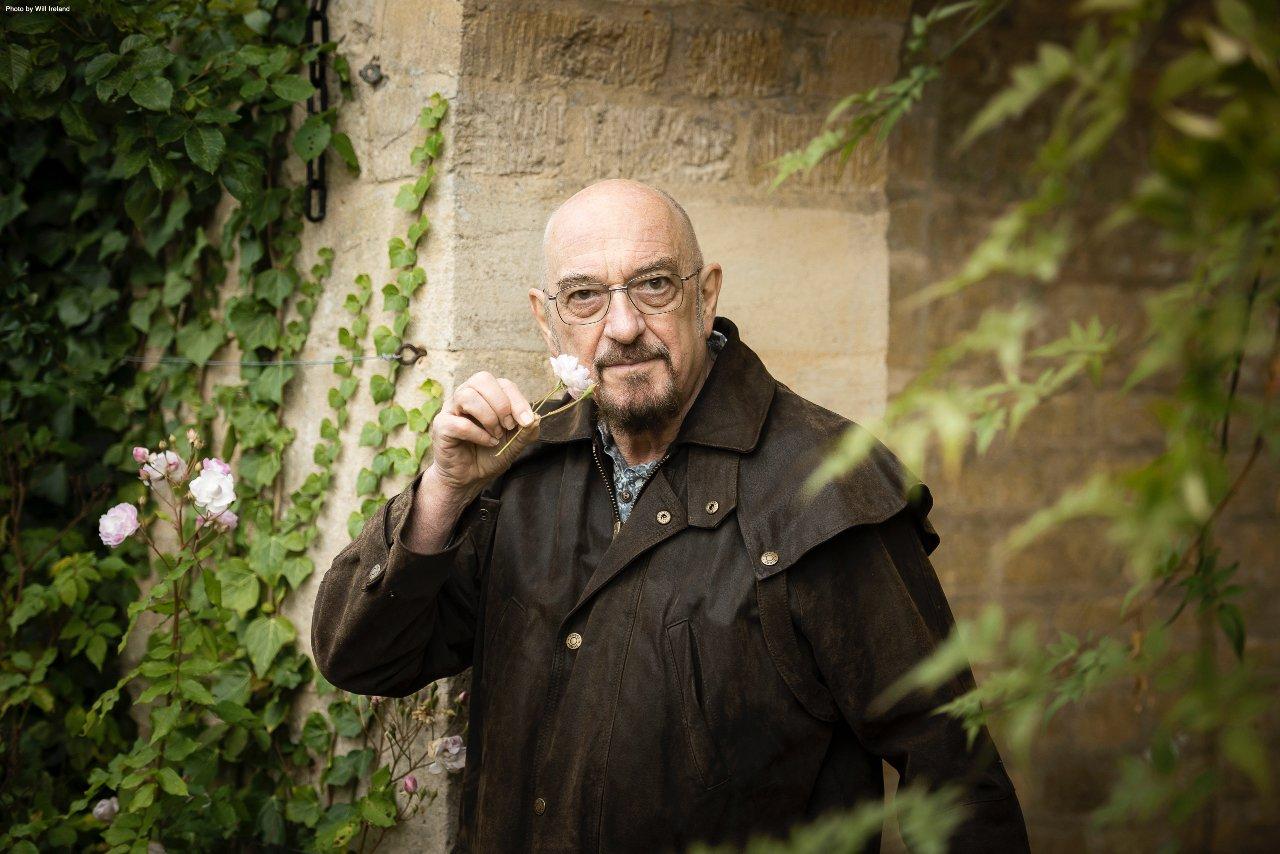

Photo: Will Ireland

interview

Ian Anderson On The Historical Threads Of Fanaticism, Playing Ageless Instruments & Jethro Tull's New Album 'The Zealot Gene'

Ian Anderson never stopped recording and touring, but 'The Zealot Gene' is the first album by his long-running band, Jethro Tull, in 18 years. Here, Anderson opens up about why it took so long — and why he plumbed humanity's capacity for militancy.

Jethro Tull has spent more than 50 years pigeonholed as the classic rock band with the flute — and largely undervalued for their wit, intelligence and heart. But that doesn't stop bandleader Ian Anderson from marveling at the very physicality of his instrument.

"Other than fine-tuning some of the mechanics and the intonation and scale of it, it's the instrument that is 175 years old now," Anderson tells GRAMMY.com, noting that Theobald Boehm perfected the Western concert flute a century before his birth. "I'm a fan of those 'forever' kind of aspects of music-making. They just go on and on and on."

This eternality doesn't just imbue Anderson's instruments of choice — he also plays the acoustic guitar, mandolin and Irish whistle — but informs what he writes and sings about. Sure, he's fascinated by modern technology — he named an album J-Tull Dot Com back in 1999, and any discussion with him is bound to be sprinkled with references to aircraft and artillery.

Read More: Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From This Was To The Zealot Gene

But these days, Anderson wants to know where our political discourse's wild-eyed fervor and immutable rhetoric flows from. And while nobody can pinpoint an ultimate origin for this psychological strain, the GRAMMY-winning progressive-rock giants' latest offering, The Zealot Gene — which arrives Jan. 28 — argues that it's millennia-old at this point. In fact, it's Biblical.

That's the name of the first Jethro Tull album in 18 years — despite several Anderson solo albums since then. (The last one was 2003's The Jethro Tull Christmas Album, partly an album of re-recordings.) Open up Anderson's 2021 lyrics compendium, Silent Singing, and you'll find scriptural citations for each song — "Mrs. Tibbets" comes from Genesis, "Shoshanna Sleeping" from the Song of Solomon, "The Betrayal of Joshua Kynde" from the Gospel of Matthew, and so forth.

Then, you'll notice the Andersonian dimensions of the lyrics — peppered with an English professor's vocabulary. And when you actually listen, you'll hear quintessential Tull — commensurately delicate and thunderous, with opportunities galore to hop on one leg a little.

Despite Anderson being the only remaining original member of the band — fan-favorite guitarist Martin Barre has been out for more than a decade — The Zealot Gene is a treasure box for Tull neophytes and diehards alike. Once an acoustic wafts in on side 2 — nodding toward those on classics like 1971's ***Aqualung ***— it's hard to hear it as anything but a return to form.

GRAMMY.com sat down with Anderson over Zoom to discuss the narrative power of Christianity, the contents of his bookshelf, and how a list of positive and negative words led him to crack open the Bible — and write the first Tull album in ages.

The last Jethro Tull album came out almost 20 years ago — obviously, you've recorded solo albums and toured all over the place since then. But why did you step away from the name for so long?

In 2011, I announced to the band that I was going to embark on a project unspecified for some point in the future. I told Martin Barre and Duane Perry, our drummer, that for the next period of time — whatever that turned out to be — I would be doing some other stuff.

I set out to do the Thick as a Brick 2 album, which is what it turned out to be once I started applying myself to a project, and since it didn't involve two members of the band who had been around for many members, I decided I should release it as a solo album rather than a Jethro Tull album.

And then, subsequently, in 2014, I released Homo Erraticus, which I also released as a solo album. Although, with hindsight, it probably would have been better to have said that was a Jethro Tull album because the guys on the album had been playing with me for many years at that point.

Later on still, when I started working on The Zealot Gene, I decided at that point that I would release it as a Jethro Tull album because the guys in the band had been playing with me as members of Jethro Tull for an average of 15 years.

It seemed like the decent thing to do — to release it as Jethro Tull so they could actually be on a Jethro Tull album, as opposed to just Jethro Tull live concert dates. So, it was written and conceived as a band album, and indeed, it started off to be just that in 2017, when we spent five days in rehearsal and four days recording to do the first seven tracks.

But because of the pressures of touring and other commitments, it didn't get finished. I think I finished four tracks in that year — that I completed vocals and flute and mixed and so on.

Then, it kept getting delayed and delayed because of the very short periods between tours, until the pandemic struck — at which point, I hoped we would get in the studio to finish it off and do the last five songs. But it was not to be, since we were in lockdown and it was unwise for us to be together in a room.

So, I ended up, at the beginning of [2021], deciding I really had to finish the album, and I would just finish the last five tracks at home. And the other guys, some of them sent in their contributions as audio files to be incorporated into the mix.

I presented it to the record company — finished, mixed and mastered — in June. Due to the delays of pressing vinyl, it was never going to be released in [that] calendar year. So, the 28th of January is the official release date due to the seven, eight months of delay and waiting to have the slot at the pressing plant to be able to manufacture.

I'm sure there are Tull fan groups grumbling about the lack of one member or another, but I think this lineup is as valid and powerful as any — especially given that some members have played with you for many years.

Well, the guitarist who is on almost all of The Zealot Gene is Florian Opahle, who left the band at the end of 2019 when he completed his recording studio near Munich, in Germany — a photographic studio to work with his wife, who's a professional photographer.

And so, he decided his touring days were over — although he did come back to do some shows in August and early September of this year, because Joe Parrish, his replacement, was not fully vaccinated at that point — a much younger guy.

So, Florian stepped in to do a few shows to help us out. It was great to have him back, but he is indeed the guitarist on The Zealot Gene — at least on seven of the tracks. Joe Parrish- James contributed a little bit of guitar on one of the remaining five tracks, just so his presence would be there on the album.

But yeah, the guys have been around for a long time. I mean, David Goodier started with me in 2004, John O'Hara in 2005. It goes back a long way working with these same members of the band. So, it's time for recognition that they are well and truly members of Jethro Tull.

After looking up all the scriptures cited in Silent Singing, I think the word "gene" says it all. You're drawing a thread from extremism in ancient history — like that account in Ezekiel of slaughtering the idolators — to what we're seeing today.

Well, it's a fanciful supposition that the human condition embraces something genetic that makes us want — as we say in English vernacular — to get our knickers in a twist.

What I'm really meaning by "zealot" is not a Biblical reference or a reference to Christian zealots, per se. I'm just talking about zealots as being fanatics — people who are fanatical about a certain topic. They could be fanatical about building model railways or attending football matches or following Formula One Grand Prix racing — or fanatical about Michelin-starred restaurants.

But, really, what I'm getting at is "fanatical" in the sense of being very firm and loudly of an opinion — which most people feel, increasingly these days, necessary to express. And freedom of speech, of course, is absolutely vital to us.

But when it starts to hurt other people — when it starts to be divisive socially in the way that populist politicians and national leaders use social media to create division in their society, to set people against each other in order to have a majority, they hope, that will allow them to maintain power — then it gets very ugly.

So, it would be easy to say that "The Zealot Gene," the title track, is modeled on Donald Trump, but that is too easy. It could be one of half a dozen people who immediately spring to mind, who are national leaders of a pretty aggressive and unpleasant sort, who epitomize that idea of being fanatical about their cause and clinging to power at all costs. That idea of fanaticism or powerful emotions runs through the album.

Indeed, it started out as a list of words. I decided I would write each song about a different kind of strong human emotion. And I made a list: some of the good stuff like companionship, loyalty, faithfulness, love — platonic love, brotherly love, spiritual love, erotic love — compassion. And then, I wrote down some bad words: things like "anger," "greed," "jealousy," "retribution."

And I looked at my list of words that I was going to, each one, pick as a subject for a song, and thought, "Oh, these are all words I recall from reading the Bible." So, I looked up all the Biblical references that readily came up in a search that would apply to those descriptions — those words.

I copied and pasted some of those verses from the Bible and put them on a file on my computer that I could use as a ready reference to draw a little comparison from. On really all but one song, I'm taking those ideas and trying to give them relevance to the world we live in today.

I think the only exception, really, is "Mine is the Mountain," which is really set in the Biblical, historical story of Moses going up the mountain to receive the tablets of stone to take down and satisfy his followers — that he was in possession of something powerful and strong that would allow him to maintain his authority and lead his followers to a promised land.

That's something I appreciate as a good narrative and gives Christianity its strength and power. It's a good story. Unlike other religions, it has a continuous narrative. It has a beginning, a fairly short middle and a very powerful ending. But the ending of it brings the promise of something more to come — i.e. series 3 on Netflix.

That's why Christianity has this enormous power as a religion worldwide. It's a narrative. It's a story. And we all love a good story — even if some of it is not entirely credible, historically speaking, or unprovable factually. But I'm a big supporter of Christianity; I just don't choose to call myself a Christian.

My favorite song on the album is "In Brief Visitation," which frames Christ as a "fall guy." It feels charged with love and wonder, but also biting humor — it's quintessential Tull in its outlook. What was going on with that song?

Well, yes, obviously, going back to my notes and the Biblical texts, we are talking about Jesus of Nazareth being, if you like, the "fall guy" for a cause. As a rather radical Jewish prophet as he was, in historical terms, almost certainly. But it's applicable to anybody who perhaps has a brief period of time to try to achieve something, but ends up suffering for the cause and being cast aside.

I think it has lots of applications in the modern world. Sometimes, bad things — because, right now, there is a trial concluding in America where a certain woman is likely to spend the rest of her life in prison if a jury finds that she should so do.

She could be referred to as a "fall guy" — carrying the can for a very dreadful person who is not allowed to face the music because he committed suicide. That's another kind of fall guy — someone who takes the rap because it's easier to pick on somebody who you can actually identify and punish.

That's a bad example in the sense of bad deeds, but there are probably other cases where people who probably do good things still end up being pilloried in some way because they're easy targets.

I think the important thing is, for me, as a writer, that I have a reason for writing something. I can bring it under an overall topic. It can sit under the umbrella of a concept, and the concept is quite simple: it's just to write a bunch of individual songs about extreme emotion.

But I like to tie it together, and that's the fact of using Biblical texts — not as an inspiration, but a little constant reminder of some examples that I can draw upon and flesh out in often contemporary terms.

I appreciate that you've never succumbed to any urge or pressure to streamline or dumb down your ideas for a wider audience. It seems like you've engendered an intelligent following for it.

I don't think it's so important that I do that to the majority of listeners. I think they are perfectly entitled to — and perhaps best advised to — just listen to the music and sing along or tap their foot and enjoy it on a relatively basic level. I don't expect people to go into the detail of what's there.

But I think for those who do want to go into what lies behind something…the general feeling was: yes, we should give the dedicated fans the detail, the information behind the album, how it came to be written, and even include the very first, rough demos that I made and sent out to the members of the band back in early March of 2017.

But I don't think that's necessarily important for the majority of people who will listen to the album — having hopefully paid for it, or downloaded it, or streamed it or whatever. They're not all necessarily interested in what lies behind it, and that's fine by me.

"Jacob's Tales" sounds like it could have been on This Was. "Mine is the Mountain" has a "My God" feeling. The synths throughout the album make me think of Crest of a Knave. Was it a conscious decision to touch on the sounds of Tull's various eras?

Hardly at all. They're just the instruments we play. Essentially, the instruments I play are the instruments I've been playing since I first began professionally.

I play the acoustic guitar; I use it for writing the majority of songs I've written over the years. And I play the flute — another acoustic instrument — and other acoustic instruments which occasionally appear on records. Mandolin, harmonica and the Irish whistle — these things appear on this album in small measure, but they're there.

So, I'm an analog, acoustic kind of guy as a performer. And when you look at the guitars that get played — our bass player plays a Fender Jazz Bass. It's from the 1960s. Our guitar player — well, Florian, on the album — he's playing a Gibson Les Paul, which is another vintage, late-'50s, early-'60s.

And John O'Hara plays the piano and Hammond organ, which, again, are instruments that are part of the history of pop and rock music as well as jazz. And, in the case of piano, of course, it forms a major part of classical music.

So, the instruments we use are fundamentally embedded in the world of contemporary and older forms of music — there's nothing particularly clever about that, technologically. I think where the technology comes in is into the actual recording process, where everything is digitally recorded, mixed and mastered. That's the bit where the technology is contemporary.

I like to embrace the traditions of music-making and incorporate those into modern technological ways of bringing it to the ears of the public. That's my approach to making music, really — it's a mixture of old and new.

And when I get on an aeroplane, very often, I'm sitting on a Boeing 737 — another product of the '60s, still flying today. [There are] several editions further on, but nonetheless, it still looks like the Boeing 737; it smells like the Boeing 737. You know, if you were to pick up the average handgun belonging to a policeman — assuming he would let you do it — you would see inside the magazine some 9mm Parabellum ammunition.

It's been around since the very beginning of the 20th century as the ammunition caliber that is probably, more than any other — in terms of sidearms — been the gold standard. If you can call it that, given that it is something primarily used for killing people. Except, if I have it in my hands, I'm just making holes in a paper target, so that's OK. However, a lot of things seem to go on forever. They seem relatively unchanged in many ways. I rather like that.

The flute I play is an instrument that was designed by Theobald Boehm exactly 100 years before I was born. And essentially, it's still the flute that you would buy if you were a student learning to play the flute, or you were a soloist in the world of classical music… I'm a fan of those "forever" kind of aspects of music-making. They just go on and on and on.

Obviously, we've all flirted with the analog synthesizers of the '70s and the more exotic sampling and sequencing keyboards of the '80s and the '90s. But they are there almost as a substitute for the real thing…for a classical grand piano, or a substitute for a church organ or Hammond organ. It's a matter of convenience, but essentially, not a busting amount has really changed.

So, we're still flying in a Boeing 737 most of the time, in musical terms.

You mentioned the Ghislaine Maxwell trial, and I remember you telling me you'd read George W. Bush's memoir. What else are you reading about these days?

Well, I read a mixture of Nordic noir crime thrillers — just for a bit of light entertainment — and then weightier books on subjects. Comparative religion, spirituality, things to do with fairly deep, philosophical thoughts.

Sometimes, they're more contemporary, but nonetheless, somewhat philosophical by contemporary popular writers who will go into topics of everything from ecology, to climate change, through to the societal changes happening these days and where we might be headed in the future.

Again, it's the contrast that appeals to me, I suppose. If I only read one kind of thing all the time, it would be a little dull.

It seems like you're always working on Tull-related books or putting out boxed sets for various anniversaries. How would you break down an average day in your life, from a professional standpoint?

I usually get up at six in the morning — sometimes a little earlier. I come down, do a couple of hours' work in the office. And then, I usually have my morning round of promo interviews to do, if I'm working with a new project, like the album — [which] is, for me, quite demanding from a promo point of view.

So, I've got a few hours of press and promo to do in the morning, as per the European side of things, and then I've got press and promo to do in North America and other territories on very different time zones. That happens in the afternoon. I'm probably at my office desk much of the day, but I'm not actually rehearsing, practicing and playing the flute.

I'm about to start a new project on Jan. 1 of [2022]. In a couple of weeks, I will begin the next album. The great thing is that I have no idea what it's going to be about.

At nine o'clock on the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse, who — should she decide to visit — hopefully, by 10 o'clock, I'll have the beginnings of some kind of flicker of an idea. And by lunchtime, I might have a few ideas. And over the period of the next three or four weeks, I might think I'd completed the first draft of something — musically and lyrically — for a new album.

That's partly wishful thinking, and partly putting myself on the spot. I like the idea of challenging myself to do what I say I'm going to do, and usually managing to do it, as I have done since 2011 with Thick as a Brick 2, the Homo Erraticus album, the String Quartets album, the Zealot Gene album. I've set out to do those things at a certain point, and I like to think I get results.

But sooner or later, I will meet the dreaded writer's block and probably burst into tears or have to be carried into my bed.

So there's nothing to reveal about the next album, because you haven't even opened your mind to the ether yet.

Well, no. I think the thing is that if I started dwelling on that now, I would start to have some ideas, and it's too early. I just want to wait for that magic moment to present itself.

Jethro Tull

Photos (L-R): Ricrdo Rubio/Europa Press via Getty Images, Martyn Goddard/Corbis, Pete Cronin/Redferns, Hulton Archive via Getty Images

feature

Songbook: A Guide To Every Album By Progressive Rock Giants Jethro Tull, From 'This Was' To 'The Zealot Gene'

Despite being a staple of 1970s rock, Jethro Tull remain bizarrely underrated — they're one of the most cerebral, idiosyncratic and affecting bands of all time. With their comeback LP 'The Zealot Gene' on the way, here's a guide to their 22 albums.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond.

Ian Anderson recently released Silent Singing, a full compendium of his lyrics with his band, Jethro Tull, and from his solo career. He doesn't expect most people to seek it out, much less absorb it — and he's perfectly OK with that.

"They are perfectly entitled to — and perhaps best advised to — just listen to the music and sing along, or tap their foot and enjoy it on a relatively basic level," the bandleader tells GRAMMY.com of the book, which spans his life's work since 1968. "They're not all necessarily interested in what lies behind it."

In other words, Anderson's not here to lecture listeners about the wonders of cutting-edge technology, the corruption of organized religion, or the joys of animal life. He makes rock songs, not TED Talks.

But what if you do want to dig deeper than the top-line information about Tull? Anderson put out Silent Singing for the more invested portion of his fan base — those who know his art beyond the famous Anchorman scene.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//f7SGq7jMdSU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Flip to even the most obscure entry, like the one for "Wond'ring Again," a sequel to Aqualung's love song "Wond'ring Aloud," buried in the 1972 compilation Living in the Past, and the cerebral, furious and evocative lyrics might blow your hair back.

"The excrement bubbles / The century's slime decays," it goes. "Incestuous ancestry's charabanc ride / Spawning new millions, throws the world on its side." Unfurling its predecessor's purview until it encompasses everything, Anderson condemns an overpopulated, coarsening society plundering its only home. It’ll give you goosebumps if you're in the right mood. It's quintessential Tull.

Wielding a freight-train intellect, a bookworm's vocabulary, and underdiscussed melodic gifts (despite his limited vocal range), Anderson has penned a few dozen tunes that belong in the Tower of Song — from the white-knuckled "Locomotive Breath" to the enchanting "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All" to the exquisite "Moths." And the more you plumb beneath the surface — the riffs, the flute, the, er, codpiece — the more rewarded you'll be.

On Jan. 28, the English progressive rock titans are back with The Zealot Gene. It may be their first album in almost two decades, but their idiosyncratic vision remains undeterred. Drawn from Biblical accounts and morality lessons, songs like "Shoshana Sleeping," "The Betrayal of Joshua Kynde" and "In Brief Visitation" peer under the hood of the human condition like only Anderson can.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://open.spotify.com/embed/playlist/2dwK0Gx6D9s3YotJLMeBuC' width='100%' height='380' frameBorder='0' allowtransparency='true' allow='encrypted-media'></iframe></div>

Despite Tull's considerable creative powers — and being a staple of hard-rock radio — they remain bizarrely underrated. Like fellow '70s hitmakers Randy Newman and Steely Dan, the press has pigeonholed them with superficial characterizations. The mordant Newman is most famous for Toy Story, so he must be a cuddly, harmless artist; the black-humored Steely Dan jammed with jazz legends and projected laconic cool, so they must be a yuppie-friendly yacht-rock act.

As for the erudite Tull, perhaps their theatrical goofiness and "Dungeons & Dragons"-style album art backfired in that department. But they've always had bigger fish to fry than being cool. Leave your preconceptions at the door, maybe hop around on one foot a little, and you're in for musical treasures galore — from poetic outpourings to horny musings to sober inquiries into a higher power.

These days, Anderson is the only remaining original member of Jethro Tull. They've had numberless lineups across the decades, and longtime, fan-favorite guitarist Martin Barre left in 2011. But if the patina of The Zealot Gene is any indication, still more captivating work may lie ahead of Anderson and his cohorts — even with their best-known music a half-century behind them.

In the latest edition of Songbook, GRAMMY.com rings in the impending release of The Zealot Gene with a deep dive into every album from the band's still-underdiscussed discography — from their blues-rock beginnings to the folk trilogy to their work in the 21st century.

(Editor's note: This list focuses on the core Jethro Tull discography and excludes compilations and Anderson's solo albums.)

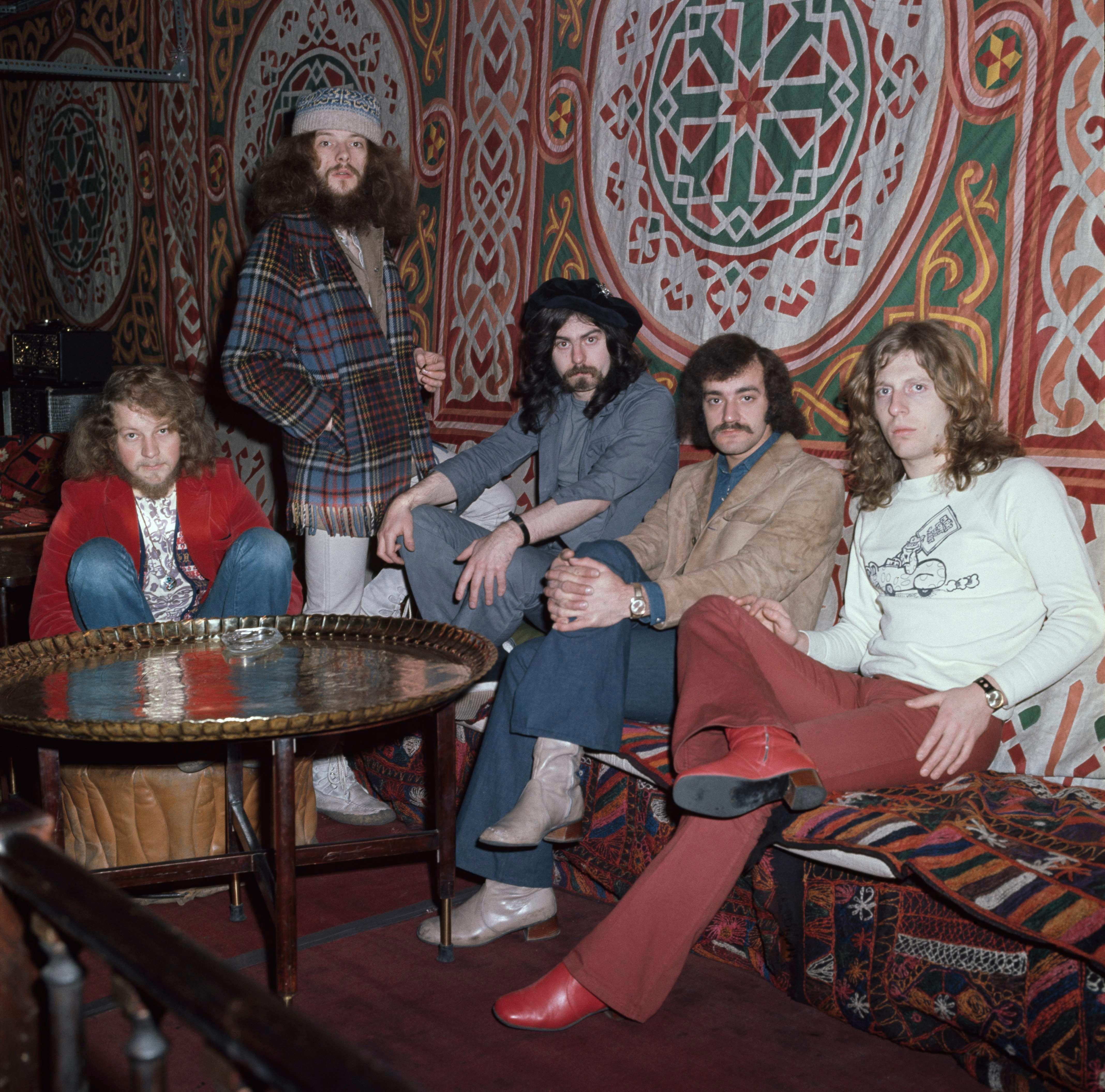

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images

Named after an 18th-century agriculturist, Jethro Tull began as a fairly typical blues/rock combo with one important distinction: the flute.

This Was (1968)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//6dPsGwnsdtk' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Jethro Tull's debut is less the vision of Anderson than of their original lead guitarist, Mick Abrahams, who appeared on a grand total of one record — this one.

A mostly straightforward blues/rock album, This Was features an instrument that immediately distinguished Tull from their peers. (Try and guess which one.)

This was intentional on Anderson's part. In a British rock scene with a preponderance of white-boy guitar shredders, Anderson demurred and took a different tack.

"I wasn't sure when Ian turned up with the flute," Tull's drummer at the time, Clive Bunker, said in their 2019 oral history The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I said, 'Look, Ian, it's a blues band, not a jazz band.'"

The eccentric Anderson stood out in other ways, too. "Ian was a good performer, but he was a strange man and I was confused," Abrahams recalled in the same book. "I remember seeing him shambling down the street wearing an old shabby overcoat, hair and beard all over the place, carrying a toilet bowl he'd pinched from the Savoy cinema."

As creative partners, the open-minded Anderson and blues-purist Abrahams weren't to be, but the one album they made together is a low-demand pleasure — and an enjoyable product of its time and place.

This especially goes for the rollin'-and-tumblin' "My Sunday Feeling," and "Dharma for One.” The latter features an invented "claghorn" — an amalgam of an ethnic bamboo flute, the mouthpiece of a saxophone and the bell of a child's trumpet.

The most well-known tune here is "A Song for Jeffrey," a harmonica-driven tribute to future Tull bassist Jeffey Hammond that doubles as a roast (before Hammond officially joined the band, he and Anderson were classmates). "Gonna lose my way tomorrow/ Gonna give away my car," Anderson sings. "Can't see, see, see where I'm going."

But Anderson had a pretty good idea of where he was headed — as foreshadowed by that rearview mirror of a title.

Stand Up (1969)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//MkF_dn3ni5g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

By 1969, Abrahams was out of the band. And in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, Anderson claims the pair were “never close,” noting his diametrically opposite nature: "I wasn't one of the lads. I didn't drink beer or smoke marijuana and hang out."

Barre soon replaced Abrahams; he would stay in the band for decades and perform on their most beloved works. And from the outset, he proved himself to be as eclectic and open-minded as Anderson needed him to be.

"Martin Barre wasn't a blues guitarist like Mick Abrahams," Anderson noted in the book. "I could see the possibilities."

With a simpatico co-pilot on board, Tull recorded their first truly excellent album — one that acts as a Rosetta Stone for their output throughout the following decades.

Barre's scorching lead parts on "A New Day Yesterday" foreshadow the mighty Aqualung, a jazzy rendition of Bach's "Bourée" displays their high-minded purview, and the international flavor of "Fat Man" gestures toward their '90s embrace of global sounds.

"It's progressive in that it reflects more eclectic influences, bringing things together and mixing and matching and being more creative," Anderson told Louder Sound in 2018. "For me, it's a very important album — a pivotal album."

Benefit (1970)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//9OZMgUu3B9s' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

An album borne of exhaustion with the touring lifestyle, Benefit introduced an anxiety and ache to Tull's sound — a vibe that would take flower on Aqualung. The songs also became slippier, more mysterious, more elliptical — partly thanks to a key influence in an English progressive folkie.

"Roy Harper, who I came to know quite well, wrote songs that were so personal and frighteningly intimate," Anderson noted in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I found it fascinating being drawn into this sexual intimacy, but having no idea who the other person in the song was."

This vibe made it into songs like "Alive and Well and Living In," which obscures its subject: "Nobody sees her here/ Her eyes are slowly closing," "If she should want some peace, she sits there without moving/ And puts a pillow over the phone."

Elsewhere, "Sossity: You're a Woman" is their first knockout acoustic ballad in a career full of them. (Honestly, if you only seek out Tull's quieter selections, you'll still find the essence of the band.)

But most telling of all is "For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me." The track was inspired by astronaut Collins, who remained in the command module of Apollo 11 as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked the lunar surface. (Advertently or not, that sums up the loneliness of touring life.)

Despite intriguing moments like these, Benefit mostly functions as the connective tissue between two eras of Tull and the ramp-up to a stone-cold classic.

Photo: Michael Putland via Getty Images

Jethro Tull's sound became increasingly dynamic and diverse, dealing in themes including organized religion. On successive releases, their ambition only grew more outsized.

Aqualung (1971)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//61PMgwdGOQg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

If you can believe it, Tull's signature song, “Aqualung,” contains no flute. But it contains more than most give it credit for — an ocean of pathos.

Atop Barre's six-note thunderclap of a riff, Anderson snarlingly describes the titular, itinerant character, who wanders the frigid streets in raggy threads, leering at neighborhood girls.

If that was all "Aqualung" was, though, it wouldn't be much — a sudden dynamic shift into a hushed, acoustic ballad goes for the heart. Instead of judging the pathetic vagabond, Anderson notes his loneliness, isolation and marginalization. Most touchingly, he addresses him as "my friend."

"[I was] not trying to imagine much about his life, but more in terms of our reaction to the homeless," Anderson told GRAMMY.com in 2021. "I felt it had a degree of poignancy because of the very mixed emotions we feel — compassion, fear, embarrassment."

After that momentous introduction, Tull leads listeners through an astonishing song cycle about the rot of organized religion ("My God"), domestic tranquility ("Wond'ring Aloud") and the dangers of overpopulation ("Locomotive Breath").

"'Locomotive Breath' was incredibly difficult to do," Anderson recalled in the oral history. "You have to keep the lid on the thing, like a boiler building up pressure."

Aqualung crescendos with perhaps the most powerful song ever written about the difference between God and church: "Wind Up," where the Highest addresses Anderson directly. He's a personage with thoughts and feelings, He informs Anderson — not just on Sunday morning, but 365 days per year.

In the bridge of "Wind Up," Anderson's incredulity and rage say it all. While he says his spiritual beliefs haven't changed since 1971, his rejection of dogma only seems to stoke his fires as a seeker of truth.

Thick as a Brick (1972)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//9jNLYCudQW4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Is there any more tired rock-critic construction than the "concept album"? Back in 1972, Anderson didn't seem to think so.

"I figured … that I'd give people the mother of all concept albums," he said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, "by taking the mickey out of some of our peer group who were now doing concept albums that were overblown and silly." (Genesis and Yes, he was looking at you.)

Thus was the impetus for Thick as a Brick, which Tull originally released as one 43-minute song across two sides. After the umpteenth shifted meter and goofy breakdown, the gag wears somewhat thin across its runtime — even with lovely moments sprinkled throughout, like the "Poet and the Painter" section.

But its flaws takes nothing away from the album's sublime first movement, titled "Really Don't Mind” in a 2015 remix and remaster. Seemingly taking shots at intellectual elitism and a drain-circling culture, it’s one of the clearest available windows into Anderson's worldview.

"The sandcastle virtues are all swept away," he warns, "in the tidal destruction/ The moral melee." And if only for the radiant and pointed three minutes that open the record, Thick as a Brick belongs in any rock fan’s collection.

A Passion Play (1973)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//-z0MvdOdV3Y' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

By far, the most priceless take on A Passion Play comes from a Melody Maker clip about a Wembley concert, where Tull played this baffling, colossal suite front to back. Think Thick as a Brick but even more scattered, with Anderson skronking on the saxophone throughout.

"The lyrics or story of A Passion Play did not communicate one whit," journalist Chris Welch wrote, horrified, in a piece headlined "Crime of Passion." Even more dramatically, "After the show, I felt uncomfortable and filled with inner torment."

An ambitious program about an afterlife-dweller accompanied by a bonkers stage show upon its release, A Passion Play is a head-scratcher — and its creator admits it.

"I didn't practice enough, I wasn't trained, and it hurt my lip," Anderson admitted in the oral history of his questionable sax chops, calling A Passion Play "in the bottom third of Jethro Tull albums." (Elsewhere, he called it "the step-too-far album.")

Are there decent moments? Sure, like the relieving appearance of acoustic guitar in "The Silver Cord" and "Overseer Overture," and the percolating ending of "Memory Bank."

But at the end of the day, if you're looking for Extravagant Tull, there are more effective places to start.

War Child (1974)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//S5D9HZyYI6g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Written for a film that would never be made, War Child is a scaled-back, middle-of-the-road entry before five superb albums in a row. While Anderson himself called it "the last multiple outing of the dreaded saxophone" and "kind of OK," it offers three all-timers on Side 2.

First, cue up the gorgeous "Skating Away (On the Thin Ice of a New Day)," a xylophone-buoyed ode to the fragility of life. "Bungle in the Jungle" — which views citydwellers through a zoonotic lens — remains one of the band's biggest radio hits.

Another for your ongoing Acoustic Tull playlist is "Only Solitaire," which marries a gently winding melody with a lyrical purview that's acrid even for Anderson: "Brain-storming, habit-forming, battle-warning, weary winsome actor/ Spewing spineless, chilling lines."

Minstrel in the Gallery (1975)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KSqnqjLI5Dc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Finally: a worthy follow-up to Aqualung.

Recorded with a mobile studio in Monaco, Minstrel in a Gallery elegantly splits the difference between multifarious heavy rock (the title track) and string-swept balladry (almost everything else), with an unwavering eye for dynamics and atmosphere.

Its creator called it "an angrier record" and its sessions as "a little divisive"; Barre didn't see it that way. "Ian was at his writing peak on Minstrel," he said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "I don't recall any friction at all. It's just that Ian took it very, very seriously."

Anderson's single-minded vision paid off in some of his loveliest songs to date. "Cold Wind to Valhalla" is a Norse daydream where "breakfast with the gods/ Night-angels serve with ice-bound majesty." "Baker St. Muse," for its part, is a gorgeous suite about quotidian London scenes.

But then, oh: the time-capsule track. "One White Duck / 0¹⁰ = Nothing at All," a heartstopping acoustic serenade suggestive of packing and leaving, remains one of Anderson's grand slams and potentially the most bewitching tune in the Tull songbook.

A puzzle as much as a song, this darkly seductive masterwork is less listened to than communed with — preferably in solitude, deep into the night.

Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! (1976)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//wt4RA2hHoRA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Initially conceived as a stage musical, Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll: Too Young to Die! follows a washed-up character who learns lessons about youth and rebirth and nostalgia… or something. But the real hero of this story is the mixing and mastering engineer Steven Wilson.

Here’s why Wilson, who has remixed and remastered many Tull albums by now, is a magical being. What everyone thought was a just-OK Tull album, he revealed to be nearly perfect. As it turns out, the original mix was just murky enough to dull the album’s impact.

In Wilson's hands, Too Old to Rock 'n' Roll isn't just saved; it's potentially the most accessible gateway to this band. Shone until they gleam, "Salamander," "Bad-Eyed and Loveless" and "Pied Piper" contain sneaky hooks that might burrow into your consciousness.

While the cornerstones of the album might be the triumphant title track and closer, "The Chequered Flag (Dead or Alive)," the finest of them all is a very deep cut: “From A Dead Beat to an Old Greaser.”

Climbing a stair-step melody with an exquisite string arrangement, this affecting hipster tableau name-drops Charlie Parker, Jack Kerouac and René Magritte as it builds to a lithe sax solo.

Photo: Stan Frgacic/Corbis via Getty Images

Using pastoral instrumentation as a canvas, Ian Anderson explored themes of agriculture, woodland mythology and the environment under siege.

Songs From the Wood (1977)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//_XM-u9jBsMs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Spurred by the book Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain and a relocation to the Buckinghamshire countryside, Songs From The Wood is a jolly, earthy affair preoccupied with the pre-Christian old gods and all things verdant and growing.

Still, a faint thread of anxiety runs throughout, as if Anderson is clinging to the old country as it fades.

"Does the green still run deep in your heart/ Or will these changing times, motorways, powerlines keep us apart?" Anderson asks of the titular, woodland character in "Jack-in-the-Green." (Think Radagast, the wizard of nature from Tolkien's works — but small enough to drink from an “empty acorn cup.”)

Songs from the Wood isn't perfect — Side 2’s seemingly endless, guitar-squealing “Pibroch (Cap in Hand)” is seemingly included here to run the clock. Still, the litany of folky gems throughout makes it a top-shelf Tull offering.

From the springy "Cup of Wonder" to the wintry delight "Ring Out, Solstice Bells" to the randy "Velvet Green," Songs from the Wood exudes giddy, punch-drunk joy at the gift of the green country.

Heavy Horses (1978)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//7Pq55hLi6VM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Sure, songs about broken guns and hunting clothes and making love in the woods are all well and good. But on Heavy Horses, Tull took the theme further by zeroing in on animals — several songs roughly correspond to a critter found in the English countryside.

It all kicks off with "...And The Mouse Police Never Sleeps," the most deliciously bloody toast to the housecat this side of T.S. Eliot. To wit: "Savage bed foot warmer/ Of purest feline ancestry… With claws that rake a furrow red/ License to mutilate." If that doesn't sum them up, what does?

Powered by the kinetic rhythm section of bassist John Glascock and drummer Barriemore Barlow, Heavy Horses only gains steam as it hits gem after gem. "Moths" is an oblique love story imbued with magical realism; the majestic, nine-minute title track laments the obsolescence of workhorses amid the encroaching industrial age.

The crown jewel, though, is "One Brown Mouse," a rapturous ode to the banalest of household pests with a dizzying, key-toggling bridge. Drop every one of your defenses, and the song a rush of unadulterated feeling; it will pry open your heart if you let it. Smile your little smile.

Stormwatch (1979)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//M1ivxxPISZc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

With country air behind Tull, something wicked this way came. Stormwatch flips the script on its (mostly) carefree predecessors, zeroing in on weather and the environment. Appropriately, the music sounds salty and eroded, like a schooner battered by a tempest.

After the opener "North Sea Oil” needles the petroleum business, the fraught vibe only unspools from there. In "Orion," Anderson addresses the titular constellation as it indifferently observes the world’s dramas; in "Something's On The Move," he tackles climate change decades before Greta Thunberg.

Sure, it’s all a touch dreary and monochromatic, but that’s part of its charm: Stormwatch is a rock-solid Tull album with a vividly rendered moral compass.

The power ballad "Home," with guitar-monies beamed overhead like the Aurora Borealis, stands out in particular. So does the weatherbeaten ballad "Dun Ringill" — which, with its disembodied, spectral whispers, sounds like a dispatch from Davy Jones' Locker.

Photo: Pete Cronin/Redferns

At the top of the 1980s, Tull sensed the winds of change and interwove synthesizers into their sound.

A (1980)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KLiNxL7RrcQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Is it jarring to see Jethro Tull playing synth-inflected music in jumpsuits? That’s fair: A was never meant to be a Tull album, but — hence the initial in the title — an Anderson solo album. hence the title. But thire record label, Chrysalis, didn't think it would sell under his name.

"Barrie, [keyboardist] John Evan and I all received the same, cheap carbon copy of a letter explaining that the record company had decided to release Ian's latest recordings as a Jethro Tull album," synthesist and arranger Dee Palmer said in the oral history. "Our services were no longer required."

This, along with other factors, led to upheaval within the camp and the departure of multiple members. Taken together, these factors make A an odd duck in the catalog, but listening today, it's by no means an embarrassment.

Thanks in no small part to its remaster — thanks again, Steven Wilson — songs like "Crossfire," "Fylingdale Flyer" and "Protect and Survive" show that Anderson's pop instincts remained undimmed, no matter the aesthetic or context.

Plus, it ends with two great, underdiscussed tunes — the giddy instrumental workout "The Pine Marten's Jig" and capacious closer "And Further On."

The Broadsword and the Beast (1982)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//yvHPaRGcv8g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

While synths occasionally trapped A in amber; they're woven in far more seamlessly on its follow-up. "We took the new technology and married it with folk-rock," Anderson explained in The Ballad of Jethro Tull, calling it "a good album and full of light and shade."

Indeed, The Broadsword and the Beast is a welcome return to form, with synth textures adding vividness and color to the songs. Despite tanking in America — probably due to the very non-single title track being the single — the record fits snugly with their '70s masterworks.

From the feisty "Beastie" to the irresistible "Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow," excellent tunes abound here. But the inarguable centerpiece is "Jack-A-Lynn": a downcast acoustic ballad studded by a melancholic synth motif and, eventually, detonating into stadium rock.

Under Wraps (1984)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//eo9fJO8JD5E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Speaking of the 1980s, "I don't think Ian should have ever attempted to keep up with the modern trends," then-bassist Dave Pegg said in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. ("But he wasn't alone — everybody else was doing it too,” he qualifies.)

This seems to sum up the problem with the leaden, electronics-heavy Under Wraps. While the majority of tracks, like "Lap of Luxury," "European Legacy" and "Saboteur," are probably best left uninvestigated, there's one decent tune here — and one gorgeous one — to add to circulation.

Respectively, those are "Paparazzi" — which actually does something angular and intriguing with the dated palette — and "Under Wraps #2," which strips down the instrumentation for a sweet, simmering love song with charming call-and-response verses.

Crest of a Knave (1987)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//LySTISqaH9o' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Crest of a Knave may be one of Tull’s most surprising and thrilling returns to form, but its reputation precedes it in a different way.

Sadly, it's forever tethered to the upset at the 1989 GRAMMY Awards, where it beat Metallica's …And Justice For All in the Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance category. (Afterward, Anderson took out a full-page Billboard ad, which simply read "The flute is a heavy, metal instrument.")

At this point, however, it's time to consider Crest of a Knave apart from this well-worn anecdote. Fact is, it may be Tull's final truly great album until The Zealot Gene more than 30 years later.

The album begins thrillingly with the vertiginous "Steel Monkey," where a knuckleheaded skyscraper worker tries to get fresh with a woman. The obviously sequenced synths and programmed drums don't stifle the tune one iota — true to the industrial theme, they make it pump and slam like hydraulics. As Anderson's character gloats about his high-flying lifestyle, a skyward key change puts you right there — 300 feet above the ground.

Elsewhere, "Farm on the Freeway" addresses infrastructure's threat to American farmers, and "She Said She Was a Dancer" sardonically casts Anderson as an out-of-his-depth Western rocker trying to pick up an Eastern European.

Despite its very 1987 production, Crest of a Knave is a triumph purely on its own terms.

Photo: Martyn Goddard/Corbis via Getty Images

While grunge reigned in the '90s, Tull returned to their heavy-blues roots and branched into global sounds.

Rock Island (1989)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//cKhw2H8jaic' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Like A Passion Play and Under Wraps before it, Rock Island could probably vanish from the catalog without altering the narrative. Which doesn't make it bad, exactly — save for the wince-worthy sexual innuendo of "Kissing Willie."

Anderson has publicly expressed fondness for at least three tunes. In the oral history, he praised "The Whaler's Dues," which he praised as "representing something that had happened historically but still had some relevance today"; and closer "Strange Avenues," which he called a "very spooky, moody piece of music."

In Silent Singing, he cited "Another Christmas Song" as "probably my long-term favorite, oozing nostalgia, reflection, and dislocated family relationships.”

But after you throw those tunes on your Tull playlist, seek out Rock Island's follow-up, Catfish Rising, for a far more engaging example of what the band could do at the close of the '80s.

Catfish Rising (1991)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//lj0IV9ZTVnU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

That's more like it: Catfish Rising was Tull's richest, loamiest album since Crest of a Knave.

A return to ballsy hard rock in the ballpark of Stand Up, Catfish remains strangely overlooked in the oeuvre. It's the moment they emerged from the miasma of the '80s, happily remembering what made them special in the first place.

This doesn't just mean 12-bar shuffling — although "Still Loving You Tonight" is a decent throwback in that regard — but outfitting that palette with acoustic instruments like mandolin and mandola, which has always been Tull’s specialty.

Despite not containing their deepest material, Tull listeners should know a few selections on Catfish Rising: "Sparrow on the Schoolyard Wall," "White Innocence" and "Gold Tipped Boots, Black Jacket and Tie," to name a few.

Even while miles away from the heights of Aqualung and Minstrel in the Gallery, returning to the blues’ gravitational center kept Tull healthy and robust into the '90s.

Roots to Branches (1995)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//VN8VJp8Gdn4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Could Tull have successfully drifted into the remainder of the '90s as a new-age band with a Middle Eastern tint, like latter-day Popol Vuh? Roots and Branches makes a compelling case for that direction.

For once, the songs are secondary to the feeling: Roots to Branches captures the specific moment where classic rockers made "exotic" works during the CD reign. With each synth sweep and reverberated sidestick, the humid-rainforest vibe deepens.

While the album contains more ambiance than anything, a few gems reveal themselves with time — such as the Arabic-influenced ode to jewelry, "Rare and Precious Chain" and the atmospheric, after-hours piano ballad, "Stuck in the August Rain."

Altogether, though, Roots to Branches is one for deep heads, not neophytes. (Unless "dreamily dated" is your jam — in that case, fire it up.)

J-Tull Dot Com (1999)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//gOqUvK9ZvSg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

From the title to the typography to the too-anatomically-correct album art of the Egyptian god Amun, J-Tull Dot Com can be a tough one to defend at first. But if you can get past the packaging, there's very little actually wrong with the album — well, other than "Hot Mango Flush."

The skulking "Hunt By Numbers" is another one of Anderson's (always welcome) songs about cats. Following that is the beguiling "Wicked Windows," which may be the only song ever written about eyeglasses — and despite the stilted drum production, it’s an imaginative beauty.

Named after the band's first registered website, "We did it in my studio and we rehearsed it and played it live in the same way as we did Thick as a Brick,” Anderson explained in The Ballad of Jethro Tull. "J-Tull Dot Com had a high-tech title but was relatively low-tech music."

With that clarification in mind, feel free to find a used copy and party with Amun. Still, there are so many worthy alternatives — especially for first-time listeners.

The Jethro Tull Christmas Album (2003)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//GCkOKhCEQNw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

What would be Jethro Tull's final album for 18 years —Anderson released solo albums Homo Erraticus and Thick as a Brick 2 in the interim — wasn't really a collection of new material. Rather, it contains re-recordings of old songs and variations on Christmas classics, like "God Rest Ye Merry Gentleman."

If you're a committed fan who needs a little yuletide Tull, it'll do in a pinch. For everybody else, The Jethro Tull Christmas Album is mostly worth hearing for the lovely, updated versions of oldies "A Christmas Song" and "Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow."

Photo: Ricardo Rubio/Europa Press via Getty Images

After time off from the name and the departure of longstanding guitarist Martin Barre, Anderson and his latest cohorts have made a triumphant Tull album.

The Zealot Gene (2022)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://open.spotify.com/embed/track/1IhW1JjA4A8euFYXV2swU5?utm_source=generator' width='100%' height='380' frameBorder='0' allowfullscreen='' allow='autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; fullscreen; picture-in-picture'></iframe></div>

Even though Anderson's never stopped recording and touring, it's bracing to hear the first music under the Jethro Tull name in ages.

Questions abounded upon its announcement: would it be a bunt, like J-Tull Dot Com, or a grand slam, like Crest of a Knave? Would the absence of Martin Barre diminish the music?

Fortunately, this lineup, which includes longtime bassist David Goodier and keyboardist John O'Hara, is as valid and robust as any before it. And the album they made together, The Zealot Gene, hits all the marks that make the band stupendous and singular.

For starters, Anderson is as literate and layered a lyricist as he ever was. Still, he's never out to merely flaunt his vocabulary (despite employing verbiage like "sacrum," "perfidious" and "rostrom"). There's a refreshing, human element to the songs, which pull from accounts as old as time to explain how our species got in such a mess.

In "Mine is the Mountain," the wrath of the God of the Pentateuch radiates — you feel His judgment. True to its roots in the erotic Song of Solomon, "Shoshana Sleeping" has an anticipatory, heart-racing quality. And "In Brief Visitation" flips the account of Christ's death into a meditation on the concept of "fall guys."

Just as happily, The Zealot Gene isn't an aural monolith, but something of a tour through Tull's various styles over the years. The harmonica in "Jacob's Tales" recalls This Was; the synths in "Mrs. Tibbets" recall Crest of a Knave; the acoustic suite near the end recalls Minstrel in the Gallery.

Seemingly galvanized by the finished product, Anderson is already writing another Tull album: "On the first of January, I will open my mind and heart to the visiting muse," he recently told GRAMMY.com. "That's partly wishful thinking, partly me putting myself on the spot."

Even after half a century, the minstrel has reams left to sing — and say.

Bob Dylan

Photo: Deborah Feingold | Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment

news

Bob Dylan's Latest Box Set Proves He Remained Stellar In The '80s. These '60s Classic Rock Artists Did, Too.

A revelatory new box set, 'Springtime In New York,' proves that Bob Dylan was still a force of nature in the '80s. It's worth reexamining other classic rock artists' output during the rocky decade.

What do you think of when you consider 1960s artists in the '80s? Washed up, adrift, lost in a sea of emerging technology? You're not alone — Bob Dylan considered himself as such in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles.

"I hadn't actually disappeared from the scene, but the road had narrowed," he wrote. "There was a missing person inside of myself and I needed to find him." (He also calls himself "whitewashed and wasted out professionally" and "in the bottomless pit of cultural oblivion.")

This is coming from the guy who gave us "Every Grain of Sand," "Jokerman" and "Blind Willie McTell" during that decade, went full wild-eyed Christian-preacher mode in concert, and destroyed the universe on "Late Night With David Letterman" backed by fiery punk band the Plugz. Whatever his internal state at the time, he was selling his creative output short.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//di6wU11_4Wg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Read More: Here's What Went Down At Bob Dylan's Mysterious "Shadow Kingdom" Livestream Concert

This suspicion — or conviction — that true Dylan heads have always had is now Gospel truth. Springtime in New York, a five-disc smorgasbord that arrived in September, strips away the sometimes-overbearing production of albums like Empire Burlesque, revealing their core components: Dylan in the midst of a spiritual awakening, backed by killer accompanists like the Dire Straits' Mark Knopfler.

So, Dylan has been handed a liferaft from the '80s, a decade thought too often as a sinking ship for him and his contemporaries. Sure, some '60s artists hit creative snags in big ways, and admit as much. Paul McCartney's film and soundtrack Give My Regards to Broad Street didn't quite make it out of the era; the now-prolific David Crosby only released one album, Oh Yes I Can; so on and so forth.

But does this hold true for George Harrison, who rejoined the music industry with a blazing smile on Cloud Nine? What about the Kinks, who handled the curves of the arena-rock and punk eras then hit a grand slam with State of Confusion? Or Jethro Tull, whose Crest of a Knave earned them their first GRAMMY (to the chagrin of Metallica fans)?

Clearly, there's a larger disconnect at play. So let's examine 10 excellent albums by artists most associated with the '60s who put out great work in the '80s.

John Lennon & Yoko Ono — Double Fantasy (1980)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/5ZfxwZ0y558' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Believe it or not, Lennon's final album — the one that gave us jewels like "(Just Like) Starting Over," "Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)" and "Watching the Wheels" — earned scathing reviews upon its release.

NME, in particular, wished Lennon had "kept his big happy trap shut until he had something to say that was even vaguely relevant to those of us not married to Yoko Ono." The critics changed their tune after Lennon's slaying mere weeks after its release. But even if he were still with us (and how sweet would that be?), Double Fantasy would remain a milestone.

Picture this: After four chaotic decades in which Lennon lost his mother young and made (and unmade) the most significant rock band of all time, he had a transformative experience on a yacht from Rhode Island to Bermuda, in which a severe tempest forced him to take the wheel alone for several hours. He whooped sea shanties and took it as a baptism.

"I was so centred after the experience at sea that I was tuned in to the cosmos – and all these songs came!" he later said. They were unlike any others he'd written.

The Rolling Stones — Tattoo You (1981)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed/SGyOaCXr8Lw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

It's fascinating to watch the "Beatles or Stones?" debate percolating in the media again, because we get to be reminded of how it's a false dichotomy.