Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

interview

"Rhapsody In Blue" At 100: Why George Gershwin's Hotly Debated Masterpiece Still Resonates

What a tangled web we weave with "Rhapsody in Blue," from race to class to the classical repertoire and beyond. But a talented pianist's reimagining underlines that Gershwin's 1924 crossover hit still pulses with life.

It was weeks before the "Rhapsody in Blue" centenary, but Ethan Iverson still tore a hole in the Gershwinverse.

In a controversial New York Times opinion piece titled "The Worst Masterpiece: 'Rhapsody in Blue' at 100," the jazz pianist and composer called the classical crossover hit "corny and caucasian." And despite applause from the Black musical architects it drew from, like Art Blakey, Billy Strayhorn and Tadd Dameron, "The promise of 1924 hasn't been honored," Iverson asserted.

While a fairly even-handed read, "The Worst Masterpiece" reopened online fissures over race, genre, heritage, academia, the classical repertoire… the list goes on. (At press time, the debate's still actively raging on Jazz Facebook and the rest.)

Is George Gershwin's catchy, world-renowned fusion of European classical with jazz and ragtime really "naïve and corny"? Or is it a bridge built, a barrier busted, a bastion of unity in a fractionated world? What's most heartening is that we still care enough to argue about it.

Love it or loathe it, "Rhapsody in Blue" still pulses with life 100 years after its New York City premiere.

Enter Lara Downes, a celebrated American pianist who's given this "Rhapsody" her own spin via Rhapsody in Blue Reimagined. Out Feb. 2 via Pentatone, Downes' take reflects on immigration, American musical roots, and a whole lot more on her psyche.

"He was really, really influential in laying the groundwork for a lot of ideas about the way that things can go," Downes tells GRAMMY.com, "where you can infuse a symphony with jazz music music, but you're also letting symphonic sounds come into pop music."

That being said, a century has come and gone, and we're in a wildly different space regarding cultural exchange and race relations than we were in Gershwin's day.

So, for Rhapsody in Blue Reimagined, Downes felt compelled to dig much deeper into its diasporic roots — like expanding its purview to include the diasporas of Central and South America, Asia, the Middle East, and many other regions intrinsic to the development of Black American music.

"We are blessed and stuck with this piece, a flawed classic that exemplifies our nation's unsettled relationship with the originators of African American music and technique," Iverson concluded.

Which is a perfect way to sum up a piece practically begging to be built upon, in more ways than one — which will ensure we'll still be talking about it in 2124. Turn up Rhapsody in Blue Reimagined — and, then, perhaps Iverson's excellent new Blue Note album, Technically Acceptable — and keep reading for a partial list of why "Rhapsody in Blue" resonates.

It Truly Is A Melting Pot

Sure, it's a cliché, but a cliché for a reason. With "Rhapsody in Blue," Gershwin gamely attempted to cross-pollinate Black and white traditions, to at least partial success.

"Rhapsody in Blue" was commissioned by Paul Whiteman, a key figure in symphonic jazz and — for good or ill — another lightning rod as regards race and the music. The title of the concert? "An Experiment in Modern Music."

"My idea for the concert," Whiteman explained in his autobiography, "was to show these skeptical people the advance which had been made in popular music from the day of the discordant early jazz to the melodious form of the present."

Which, to be clear, is quite the claim about early jazz — at best, contestable, at worst, offensive. But Gershwin's heart was in the right place, and the result isn't just catchy as hell, but on a certain level, admirable.

"Gershwin is well aware of what he's doing, and he really doesn't give a damn what people think," Joseph Horowitz, the author of Classical Music in America: A History of its Rise and Fall, told NPR. "He wanted to bridge musical worlds that were separate."

It's Permeated With Joy

About those catchy melodies — "Rhapsody in Blue" is absolutely stuffed with them, which lends itself to a sense of effervescent joy. (No wonder so many, with such warm memories of this music, leapt out in response to that alleged Times takedown.)

Of course, race relations in America have largely been the opposite of glowing. But as a pure listening experience — an idealized space — it's easy to get swept away in its giddy grandeur.

By expanding "Rhapsody in Blue" in more ways than one, Downes has given its disciples even more to love. Not only has she extended the composition by some 10 minutes — through sheer inclusivity of forms, sounds and colors, Downes honors the immigration that still constitutes America's essence.

Its Influence Is All Over The Place

The genre-crossing visionary perhaps most vocally influenced by "Rhapsody in Blue" is Brian Wilson: when you consider the ingredients for the Beach Boys' inimitable sound, it's right up there with Chuck Berry, surf music, Phil Spector, and the Four Freshmen.

"I must have been two or three, which meant that the record was only about a year old," Wilson wrote in his memoir of the Glenn Miller version of "Rhapsody in Blue." "When [my grandmother] played it for me, I was blown away. I was transported somewhere else."

Elsewhere, you can hear its yearning, patriotic strains throughout the works of Randy Newman — albeit often sarcastically, as in the slaver's sales pitch for America, "Sail Away." Béla Fleck transcribed it.

While Gershwin's effort wasn't universally beloved by any stretch, the likes of Maurice Ravel and Arnold Schoenberg took him abundantly seriously.

And as Downes' take on "Rhapsody in Blue" demonstrates, the 100-year-old composition is best seen as a canvas for us all to paint on, not a dead-in-the-water work trotted out in concert to fill seats.

This "Rhapsody" doesn't belong to one composer, or one set of gatekeepers; it belongs to all of us.

Photo: Lauren Desberg

feature

We Pass The Ball To Other Ages: Inside Blue Note's Creative Resurgence In The 2020s

The foundational jazz label Blue Note Records has ebbed and flowed over the years, but they’re charging into the 2020s with renewed energy. Streams are way up; fresh talent is being signed left and right. And label president Don Was has a few ideas why.

When Ethan Iverson sent Don Was his new song, the crackle of frying eggs mixed with the sound of Was weeping in awe.

During the frightening early days of the pandemic, pianist and composer Iverson enlisted 44 friends and colleagues — including pianist Marta Sanchez, choreographer Mark Morris and drummer Vinnie Sperrazza — to join in song via an accumulation of voice memos on top of Iverson’s reedy, tenor voice. The tune was "The More it Changes," with the lyrics written by Iverson’s wife, writer Sarah Deming. Despite never being in the same room, they sounded like a small-town congregation — songbooks out, shoulder to shoulder.

As he cooked breakfast, Iverson’s plucky virtual choir "just made me burst out in tears, man," Was tells GRAMMY.com. "It’s one of the most beautiful summations of the eternal nature of music and the musicians who make it." On Zoom, the five-time GRAMMY winner is framed by voluminous dreads, with various wide-brimmed hats perched on instruments and furniture behind him. And as usual, when rhapsodizing about music he deems "staggering," Was zooms out, considering the whole timeline.

"It’s about us being carbon-based life forms — that carbon will just keep going, man," Was says. He raps his desk with his knuckles. "This desk was a tree." And by invoking that natural cycle of permutation and proliferation — matter never being created nor destroyed, only assuming new forms — Was sums up his job. He’s been the president of the almost century-old jazz label Blue Note Records since 2012. And when he examines the history, lineage and ancestry of Blue Note, he finds that change — transformation — is the constant.

He sees that change in Charles Lloyd, the saxophone titan who Was says is playing better at 84 than he did at 34. ("I think I’m coming into my own!" Lloyd recently quipped to Was.) He sees it in Bill Frisell, the lopsided guitar genius who still endlessly challenges himself at 71.

It permeates his day-to-day operations at the label, too. As a musician himself, Was knows the value of making adjustments when needed — like when he corrected an inconsistent batch of audiophile vinyl from the label’s 75th-anniversary campaign, without fuss or ego. Being open to adjustments is how you evolve. And Blue Note has never stopped evolving, even when some years or decades are stronger than others.

Read More: Bill Frisell On His New Trio Album, Missing Hal Willner & How COVID-19 Robbed Jazz Of Its Rapport

Like the luminaries in its roster do in their craft from time to time, Blue Note is experiencing a growth spurt — despite already making innumerable contributions to the cultural canon. Since being founded by German immigrants Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff in 1939, the label has accumulated a wealth of musical treasures from various generations, scenes and subgenres.

But as recent developments have shown, Blue Note isn’t a "dusty museum" of ancient history — Was’s words — but a still-dynamic entity with plenty of surprises left in it.

"It seemed like in every era, the artists that were signed to Blue Note were artists who had absorbed the traditions, understood the foundations of the music that came before, but pushed the boundaries and turned it into something new," Was says. "They turned it upside down, maybe, and did something brand new with it."

And by adding bricks to Blue Note’s architecture every day, newcomers to the label are doing the same thing.

Building On Tradition With New Signees

The most conspicuous sign of development at Blue Note is its intriguing array of new signees, marking another boom period for the label at the dawn of the 2020s.

Over the last few years, musicians at the helm of the New York scene — saxophonists Melissa Aldana and Immanuel Wilkins, pianists Gerald Clayton and Ethan Iverson, vibraphonist Joel Ross, and guitarist Julian Lage — have joined jazz’s arguably most prestigious family. What explains all these new notches in the Blue Note lineage?

"Probably the pandemic — more time to listen!" Was replies with a hearty laugh. Granted, they’ve always had an ebb and flow of new arrivals and folks moving on. But this latest class of musicians has him particularly enthused. Speaking to Was, one doesn’t get the impression of a honcho selling you something, but a pal who’s an authentic music fan. Even the mere evocation of Aldana’s tone on the horn seems to send shivers down his spine.

But back to the question. Is it really just that Was had "more time to listen"? The answer is more complex, of course. And it has to do with the cash flow from Blue Note’s voluminous catalog, which includes albums that represent the apogee of the artform — by John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Hank Mobley, Kenny Burrell, Lee Morgan, Andrew Hill, and scores of other leading lights.

Read More: Hank Mobley's Soul Station At 60: How The Tenor Saxophonist's Mellow Masterpiece Inspires Jazz Musicians In 2020

Was and his colleagues are always finding ways to present the Blue Note catalog in fresh and innovative ways. Their Tone Poet audiophile vinyl series, which highlights deeper selections with cutting-edge sound quality, is a particular hit; Was says they sold half a million units last year. "We could have done more, except we couldn’t get enough records pressed," Was adds. "But it’s looking better this year."

Plus, a certain singer/songwriter, signed to Blue Note at the turn of the millennium, helps keep the operation flush. "Norah Jones has really helped us to underwrite new music at the rate we’ve released — which is at least one thing a month, sometimes two things a month," Was explains. (Blue Note put out Jones' first holiday album, I Dream of Christmas, last fall.)

Take Jones’ commercial appeal with increasingly detailed and dynamic reissues of agreed-upon classics (like Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch! and Joe Henderson’s Page One) and deep cuts by well-known names (like Grant Green’s Feelin’ the Spirit and Stanley Turrentine’s Rough ‘n Tumble), and you’ve got a healthy cash flow for embracing and nurturing rising talent.

"It’s a lot of new music to subsidize," Was continues. "If you were going to start a jazz record label without a catalog, it’d be an almost impossible business."

At Blue Note’s weekly A&R meeting, Was and his colleagues comb through new music — both what they get in their inboxes and who they’re hearing murmurs about. Some of it’s great — even impressive — but they have to pass on the vast majority of it. So what’s the "wow factor" that makes Was bolt up and sign someone? To answer that, he digs into his decades as a musician, producer, record executive and all-around industry cat.

That Ineffable Something

A quarter-century ago, Was found himself producing an album by Garth Brooks. He knew Brooks as the "biggest star in the world" back then — was mightily talented and a great live act. But something ineffable happened in the studio: "He went to do his vocal, and his vocal jumped," Was recalls, comparing the line of speakers to a 50-yard line on a football field. "It was like he was behind me."

He’d only experienced that phenomenon with a handful of artists — Aretha Franklin, Mick Jagger, Bonnie Raitt. "I’ve seen [Jagger] play to 100,000 people. I saw him play to a million people in Rio, man," Was says. "If you’re far back, he’s an inch tall." He leans his scruffy visage into the camera, making eye contact: "But you feel like he’s talking right to you."

And that ability to jump — with their voice, horn, or whatever their instrument is — is what separated Melissa Aldana, Immanuel Wilkins, Gerald Clayton, Joel Ross and Julian Lage from the rest. And it’s less edifying to comb through the forensics of who met who, and when, and where, than to examine how certain Blue Note signees act as hubs of talent.

Thelonious Monk was one. Herbie Hancock is one. So is pianist Jason Moran, who recorded for Blue Note for years before striking out on his own. And so is Ross, a vibraphonist only in his late twenties.

Ross released his third Blue Note album, The Parable of the Poet, on April 15 — and it’s by far his most ambitious to date. A seven-movement work featuring heavy hitters such as alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, tenor saxophonist Maria Grand, and trumpeter Marquis Hill, the album represents a high watermark and an enticing hint as to how expansive Ross’ vision could become.

"I’ve just been about creating music with my friends, in general, and like-minded individuals," Ross tells GRAMMY.com, noting that some of these connections date back to high school. "And now that I have some opportunities to create some music and open some spaces, I’m just like, ‘I know these great musicians. I want to play with them. Also, Don, you should listen to them."

One of these friends and collaborators happens to be Ross’s best friend: Wilkins, who’s a few years younger. In Jan. 2022, Wilkins released his second album on Blue Note, The 7th Hand; Was hails it a work of sophistication and profundity. "He’s a deep thinker. There’s a conceptual foundation behind what he’s doing," Was says. "But you don’t have to know that to feel the music."

While recording for Blue Note, Wilkins feels a sense of pressure — the good kind. "I think the pressure comes from the canon, the catalog and the archive. It's just like thinking of all these musicians who have come through Blue Note and all of my favorite records that have been on Blue Note," Wilkins tells GRAMMY.com. "It's a pressure that I welcome and love, and it forces me to make sure that I produce music at the highest level possible for myself at all times."

Tenor saxophonist Aldana, who hails from Santiago, Chile, felt that importance too, while recording her 2022 debut album for Blue Note, 12 Stars. In her case, the impetus was more to be herself than to be perfect — and it resulted in intensely personal playing.

"I feel more connected to myself and my own imperfections — and I've discovered that it's the same process with music," she said in a press release. "Embracing everything I hear, everything I play — even mistakes — is more meaningful than perfection." And speaking to GRAMMY.com, Aldana reflects on her experience thus far with Blue Note.

"I haven’t experienced anything but extreme support," she says, "allowing me to record the music the way I want, like really supporting my vision." It’s this sense of solidarity, of being backed up, that allowed Aldana to take the biggest swing she could on 12 Stars. She knew the results would be part of the canon that got her going — Sonny Rollins’ A Night at the Village Vanguard chief among them. And that’s a weight to carry.

"The most meaningful thing is to be part of that legacy, to be honest," Aldana says.

Read More: Tenor Saxophonist Melissa Aldana On Emerging From Chaos, Finding Her Chilean Identity & Her Blue Note Debut 12 Stars

Speaking to GRAMMY.com in 2021 after releasing his Blue Note debut, Squint, Julian Lage laid down what signing to the label means to a jazz musician.

“Blue Note is the mecca of recorded music. All the greatest records come from Blue Note,” he said. “So, I think there's always a sense that as a jazz musician, it would be a dream to be on Blue Note because they cultivate musicians, support innovation and understand jazz as an artform — the social constructs that exist within jazz and the fact that it is an abstract art.”

Pianist Gerald Clayton, who made his Blue Note debut in 2020, tapped into the rich ore of Blue Note's legacy with his 2022 follow-up, Bells on Sand. Most notably, in the majestic "Peace Invocation," an intergenerational duet with Charles Lloyd — the legend who joked he was "coming into his own." "It’s just staggering, man," Was says of the track, as well as three other duets with his father, bassist John Clayton.

While meditating on the significance of Lloyd and his participation in "Peace Invocation," Clayton — a six-time GRAMMY nominee — considers the entire lineage that came before him.

"To feel the connection to Lloyd and to the legends of the music that recorded for the label, who aren’t even with us anymore," Clayton tells GRAMMY.com, "to feel that you’re somehow, in an official history book way, sort of connected to that, is a really honorable, wonderful feeling."

Celebrating The Past, Investing In The Future

In addition to welcoming new talent, Blue Note will honor both their history and potential in innovative ways in coming years.

The label recently announced Blue Note Africa, a co-creation with Universal that spotlights the multitudes of its continental namesake, with inaugural release In the Spirit of Ntu, a majestic album by South African pianist Nduduzo Makhathini. The label also recently acquired an archive of tens of thousands of Francis Wolff photographs from their early history, which includes alternate takes of classic jazz images that might make diehards flip. (At press time, they’re mum on plans for the images.)

Iverson is thrilled that Blue Note has the financial leverage to stay robust into the 2020s and beyond. "[Don has] got the leeway to invest in the future," Iverson tells GRAMMY.com. "And if he was a suit — just a business guy — he wouldn’t bother. But Don is actually interested in the future, and young musicians, and he’s like, 'Yeah, let’s sign the best and brightest. Give them a shot.'"

And on a personal level, Iverson finds Was a breath of fresh air in an evermore strangulating, formatted world. "As the world’s gotten smaller — as the internet has made everything sort of like a steel bearing, that’s one smooth surface, and everyone moves in a certain lockstep — I really love those old-school New Yorkers that are always fresh and idiosyncratic."

On Iverson’s 2022 Blue Note debut, Every Note is True, the communal "The More it Changes" leads off a program by a sumptuous, intergenerational trio — Iverson, bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jack DeJohnette. With a simple, diatonic approach to harmony and a classical sense of swing, the record is a psychological balm, a cozy fireplace for the brain during traumatic times. Which makes it perfect for Blue Note.

"Through COVID, people have been treating our catalog like comfort food," Was says. "It’s the same way you eat a grilled-cheese sandwich and Campbell’s tomato soup because your mom made it for you when you were a little kid and it makes you feel good in hard times."

With this momentum, Blue Note seems poised to embrace the future of music while deftly stewarding the treasures of the past. And Iverson’s "The More it Changes" seems to sum up the give-and-take through the decades and the label’s potential to keep the lamps of tradition trimmed and burning for a long time.

"The more it changes, the more it stays the same," the rough-hewn choir sings, bound by common purpose and undeterred by global turbulence. "We pass the ball to other ages; it’s how we play the game." At Blue Note, the ball rolls forward unabated; the game has rarely been this much fun.

No Accreditation? No Problem! 10 Potential Routes To Get Into Jazz As A Beginner

Photo: Kevin Mazur/WireImage.com

news

Ebony And Ivory Celebration

The GRAMMY National Piano Month playlist

Where would music as we know it be without the piano? The sound and versatile range of the instrument is unparalleled, evidenced by the instrument's prevalence in nearly every genre of music, including rock, pop, jazz, classical, R&B, blues, country, and even polka.

In 2009 the National Piano Foundation celebrated the 10th anniversary of National Piano Month, a 30-day celebration of all things piano. While news regarding a 2010 celebration has been scarce, we couldn't pass up the opportunity to help celebrate arguably the most important instrument in the history of music. On that note, here are a few randomly fun tidbits sure to augment your piano knowledge:

Johann Behrent built the first piano in the United States in Philadelphia in 1775

The term "pianist" during World War II implied a clandestine spy using radio or wireless telegraphy

In addition to musicians, many celebrities have been known to tickle the ivories including actors Clint Eastwood, Jeff Goldblum, Dustin Hoffman, and Dudley Moore. Telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell and Nobel Prize winner Albert Einstein also played the piano. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice is a classically trained pianist

A concert grand piano may have a combined string tension of up to 30 tons. (The total string tension resulting from the Pocket Piano iTunes app does not compute.)

The first note on a standard 88-note keyboard is A. The last note on the keyboard is C

Beethoven devotee Schroeder of "Peanuts" fame played "Für Elise" in "A Charlie Brown Christmas"

With the benefit of YouTube, one can find lessons on an infinite number of popular piano songs. Here you can view a brief tutorial on how to play the classic piano part for Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'"

In recognizing that music and the piano live together in perfect harmony, we present our piano-themed GRAMMY playlist featuring not only talented pianists, but recordings that would likely sound naked without the benefit of sounds emanating from black-and-white keys, strings and slabs of wood.

"Let It Be"

The Beatles, Best Original Score Written For A Motion Picture Or A Television Special, 1970

A tried-and-true Lennon/McCartney classic, McCartney has said the theme of the song came to him following a dream about his mother during a tense period surrounding the sessions for The Beatles (aka "White Album.") Macca was able to get over his tension enough to supply both piano and vocals on the track. "Let It Be" ranked No. 8 on Rolling Stone magazine's recent top 10 Beatles songs list and remains a McCartney solo concert favorite.

"How To Save A Life" (iTunes>)

The Fray, Best Rock Performance By A Duo Or Group With Vocal nominee, 2006

Perhaps an anomaly in the alternative rock genre, the Fray utilize the piano as a centerpiece to their sound, courtesy of lead singer Isaac Slade. Slade has described the lyrics for "How To Save A Life" as being inspired by a mentor experience he had with a teen musician. The song peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and has been certified triple-platinum by the RIAA.

The Romantic Master — Works Of Saint-Saens, Handel

Earl Wild, Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (Without Orchestra), 1996

Virtuoso pianist Wild is considered a true legend in the grand tradition of Romantic pianists. A prodigy at a young age, he also possessed the rare skill of perfect pitch. Among his many career highlights, in 1986 Wild was honored with the Liszt Medal by the People's Republic of Hungary on the 100th anniversary of the death of Franz Liszt. In addition to his GRAMMY win, The Recording Academy honored Wild at the 2008 GRAMMY Salute To Classical Music. Unfortunately, two years later Wild died at his home in Palm Springs, Calif.

Alone (iTunes>)

Bill Evans, Best Jazz Performance — Small Group Or Soloist With Small Group, 1970

One of jazz's preeminent pianists, Evans' playing was marked by an unparalleled combination of harmonic sophistication, skillfully articulated improvisations, complex rhythms, and soaring melodies. Fellow jazz pianists such as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock and Keith Jarrett, among others, have cited him as an influence. Alone was an album true to its title, consisting of just Evans and his piano.

"Bohemian Rhapsody" (iTunes>)

Queen, Best Pop Vocal Performance By A Duo, Group Or Chorus nominee, 1976; GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 2004

While discussion regarding this Queen classic typically centers around its lyrical meaning, beautifully layered vocals, fandangos, or air-guitar-worthy instrumental break, it's hard to forget the piano stylings of Freddie Mercury. As a young boy, Mercury studied piano formally, which served him well in his exploits in Queen. Mercury was said to have utilized the piano in writing his songs, and he played the instrument on other notable Queen tracks such as "Killer Queen," "Somebody To Love" and "We Are The Champions."

"Imagine" (iTunes>)

John Lennon Plastic Ono Band, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 1999

Arguably his most popular post-Beatles composition, "Imagine" is the title-track off Lennon's 1971 album of the same name. Written and performed by Lennon, the song not only became his signature, but a hymn for worldwide peace. The piano Lennon used to write the song is currently on display at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix.

"If I Ain't Got You" (iTunes>)

Alicia Keys, Best Female R&B Vocal Performance, 2004

At an early age, Keys took piano lessons and studied the works of renowned composers such as Beethoven, Mozart and her personal favorite, Chopin. ("I love Chopin.... He's my dawg," Keys said in an interview with The Guardian.) By the time she was a teenager, she was writing her own songs. Keys parlayed her passion for the piano into a successful recording career, evidenced by her impressive 12 GRAMMY Awards.

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas (32) (iTunes>)

Artur Schnabel, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 1975

Despite being deaf, Beethoven was not only a prolific composer, but a virtuoso pianist and a dedicated student of the instrument. Spanning the length of his career, Beethoven's 32 piano sonatas provide a captivating look at not only his musical development and proclivity for experimentation, but also a window into some of his timeless works, including the elegant "Moonlight Sonata." Schnabel, considered to be one of the 20th century's finest classical pianists, was heralded for not only his interpretations of the works of Beethoven, but also Liszt, Chopin and Schubert.

Chopin: Mazurkas (Complete) (iTunes>)

Artur Rubinstein, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 2003

Born in Poland, Rubinstein is considered to be one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. At the age of 3, he developed perfect pitch and was soon recognized as a piano prodigy. The New York Times has described Rubinstein's recordings of Chopin's 51 mazurkas, a Polish folk dance in triple meter, as unrivaled: "Chopin was his specialty...it was as a Chopinist that he was considered by many without peer."

"Ain't Misbehavin'" (Piano Solo) (iTunes>)

Thomas "Fats" Waller, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 1984

Born Thomas Wright Waller, "Fats" began playing piano at the tender age of 6 and would go on to be renowned for his mastery of the jazz stride piano style. Written by Waller, along with Harry Brooks and Andy Razaf, "Ain't Misbehavin'" was covered by luminaries such as Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and fellow jazz pianist Art Tatum. The popular jazz standard also featured rock and roll and country treatments, courtesy of Bill Haley & His Comets and Hank Williams Jr., respectively.

Gerswhin: "Rhapsody In Blue"

George Gershwin With Paul Whiteman, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 1974

Written by master songwriter and pianist Gerswhin, "Rhapsody In Blue" uniquely incorporated elements of classical and jazz music. The piece received its premiere in 1924 in New York, featuring Whiteman and his band with Gershwin playing piano. Those flying the friendly skies with United Airlines may recognize the song as it has been featured in the airline's ad campaigns dating back to the mid-'70s.

"Desperado" (iTunes>)

The Eagles, GRAMMY Hall Of Fame, 2000

Despite never being released as a single, "Desperado" is a favorite among Eagles fans, no doubt due to the dynamic combination of Don Henley's somber vocal with tasteful instrumentation marked by a memorable piano introduction. The song proved to be an early glimpse into the successful Henley/Glenn Frey Eagles songwriting partnership. "Glenn leapt right on it — filled in the blanks and brought structure," said Henley. "And that was the beginning of our songwriting partnership — that's when we became a team."

"Candle In The Wind 1997" (iTunes>)

Elton John, Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, 1997

Sir Elton began playing the piano at the age of 3 and soon after started formal lessons. Eventually he would go on to craft a piano style incorporating elements of classical, soul and pop music, and John has sustained a career spanning more than four decades. Re-recorded as a tribute to Princess Diana, "Candle In The Wind 1997" debuted at No. 1 on both sides of the Atlantic and he performed a heartfelt rendition at Princess Diana's memorial service on Sept. 6, 1997.

"Piano Man" (iTunes>)

Billy Joel, as featured on Piano Man, 1973

Though this song did not yield a GRAMMY Award for Joel, we'd be hard-pressed to not include a song describing the travails of a struggling lounge piano player on our playlist. (Besides, Joel is a five-time GRAMMY winner.)

Who are some of your favorite pianists and what are some of your favorite piano-based songs? Drop us a comment.

Chick Corea

Photo: Leon Morris/Redferns via Getty Images

news

In Remembrance: Chick Corea Played In More Ways Than One

The through-line of Chick Corea, a 23-time GRAMMY-winning pianist, and his body of work was a sense of childlike joy and discovery

Chick Corea was one of the most advanced thinkers ever to grace the piano, but he rarely spoke in terms of minor-third intervals or the Mixolydian scale. Drop into virtually anything the man said about his art, and it’ll probably hinge on two words: fun and games.

"Trust yourself to say, 'I don't know what I'm going to do next, but I'm just going to do it because it's fun,'" Corea advised in a YouTube clip in 2020 while talking about his old colleague, Miles Davis. That year, when speaking to JazzTimes, he continually circled back to the phrase, "That's not the game I'm playing." "Oh, would you call that music?" he asked in the 2019 documentary Chick Corea: In the Mind of a Master, between virtuosic runs on the keyboard. "I don't know; I don't care what it is. It's just a lot of fun, you know?"

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KOnHPr6CL3U' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Corea's fealty to fun made him into a boundless, filterless fount of ideas—great ones. They're all over his boundary-busting 1970s band Return to Forever, his luminous albums with vibraphonist Gary Burton, his Akoustic and Elektric Bands, and beyond. Talk about a batting average: across almost 90 albums, he won 23 GRAMMYs and was nominated fo/r 67. Currently, he's in the running for the 63rd GRAMMY Awards for his trio album Trilogy 2, featuring bassist Christian McBride and drummer Brian Blade.

Sadly, Corea won't find out if he'll add a 24th GRAMMY to his shelf. After a brief battle with recently-diagnosed cancer, the piano titan died Tuesday, Feb. 9, at his home in Tampa Bay, Florida. He was 79. "It is my hope that those who have an inkling to play, write, perform or otherwise, do so," he said in a statement. "If not for yourself, then for the rest of us. It's not only that the world needs more artists; it's also just a lot of fun."

And fun was arguably Corea's entire MO, from his stylistic interplay to his pianistic touch to the way he dealt with his audiences.

Armando Anthony Corea was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, on June 12, 1941. "Chick" came from "cheeky," his aunt's baby-name for him due to his chubby cheeks. His trumpeter father sat him in front of a piano at four; at eight, he began taking lessons from the Boston concert pianist Salvatore Sullo. After high school, he moved to New York City to study at Columbia and Julliard but soon drifted from academia into the nightclub circuit. Initially steeped in bebop artists like trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, Corea soon became enamored with music from south of the border.

The music of [the bebop] era was quite demanding. You had to be into it to really grasp it," Chick told All About Jazz in 2020. "Whereas when I heard Latin music, that beat I heard coming out of New York and out of Puerto Rico and out of Cuba—Eddie Palmieri and Machito and these bands—that gave me a whole other emotional outlook to music. I thought, 'Wow, this is uplifting, happy music, and it struck something.'" Corea touched on this sense of exuberance in his work with Latin-adjacent artists, like saxophonist Stan Getz, trumpeter Blue Mitchell and flutist Herbie Mann.

Corea's interest in this sphere also led him to the guitar master Paco de Lucía, a close friend and collaborator for decades; Corea wrote "The Yellow Nimbus" as a duet with him. "When we played together, I thought I would see a yellow cloud around his head, like a circle," he explained in his 2020 live, solo album Plays. ("Paco inspired me in the construction of my own musical world as much as Miles Davis and John Coltrane, or Bartok and Mozart," Corea said six years prior upon de Lucía's death.)

Latin influences also permeated Return to Forever, Corea's enchanting fusion band that always seemed to hover a few inches above the ground. But even though albums like 1972's Return to Forever and 1973's Light as a Feather were commercial successes, this wedding of musical hemispheres wasn't to court crossover success, but chase that ineffable feeling of freedom.

"It's the media that are so interested in categorizing music," he told The New York Times in 1983, a year after "The Yellow Nimbus" came out. "If critics would ask musicians their views about what is happening, you would find that there is always a fusion of sorts taking place. All this means is a continual development—a continual merging of different streams."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//jlNQBmBTiME' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Genre aside, Corea spent his life combing through every mood and format he could think of, from starlit, quasi-ambient duets (1973's Crystal Silence, with Gary Burton, to classically-minded post-bop (1981's Three Quartets, with tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker). The last few years of Corea's life marked an explosion of diversity and prolificity. In 2016, he underwent a six-week stand at New York's Blue Note club with more than 20 different groups.

Three years later, his Latin interest crescendoed with Antidote, a jubilant collaboration with the eight-piece Spanish Heart Band. "The game I like is where we become a unit," Corea said in In the Mind of a Master, released concurrently with Antidote. "Everyone's giving and taking, and all [are] creating the music."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//KFclSfwU8oY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

No matter which context he was in, Corea's effervescence is evident in his playing itself. His fluid phrasing and jewellike tone, which appeared almost fully-formed with his first two albums, 1968's Tones for Joan's Bones and Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, made even his knottiest material pleasing to the ear. About his way with a Fender Rhodes, "It's almost like his fingers bounce off the keys," WBGO's Nate Chinen told NPR in 2016. "His touch on that instrument is really distinctive. You know it's him within a note or two."

This accessibility and distinctiveness are testaments to Corea's emphasis on communicating to the listener, and he couldn't have done so if the music flew over peoples' heads. This became a primary value to Corea in the mid-'70s, when he converted to Scientology and underwent an auditing system that set him on a lifelong psychospiritual journey.

"A very simple thing happened to me right in the very beginning," Corea told The Village Voice in 1977. "I experience this in live hundreds or thousands of people in front of me—I now have the ability to give across a musical communication with clear intent. I know what I'm doing and who I'm communicating to, and I give the communication across, and I see what happens in front of me." (Corea dedicated myriad albums to Hubbard and remained a highly visible member of the controversial religion until the end of his life.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//YfG1P0nm2v8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

In what would be Corea's final album, Plays, he eschews a superstar's trappings: no backing band, no staid reverence, no canned commentary. "Here I am with my piano," he declares at the top, alone onstage. "The piano's tuned up all nice, but now we have to tune up. Yeah, we." At first, it's an awkward moment. He plays a middle A; the giggling crowd tentatively sings it back to him. One note becomes two; two becomes three, and so on.

But by the time Corea lays into a medley of Mozart's Piano Sonata in F, and George Gershwin's "Something to Watch Over Me," the gag reveals itself to be something much more profound. Suddenly, the barriers vanish. His game opens up to everyone. His fun becomes ours.

10 Essential Cuts From Jazz Piano Great McCoy Tyner

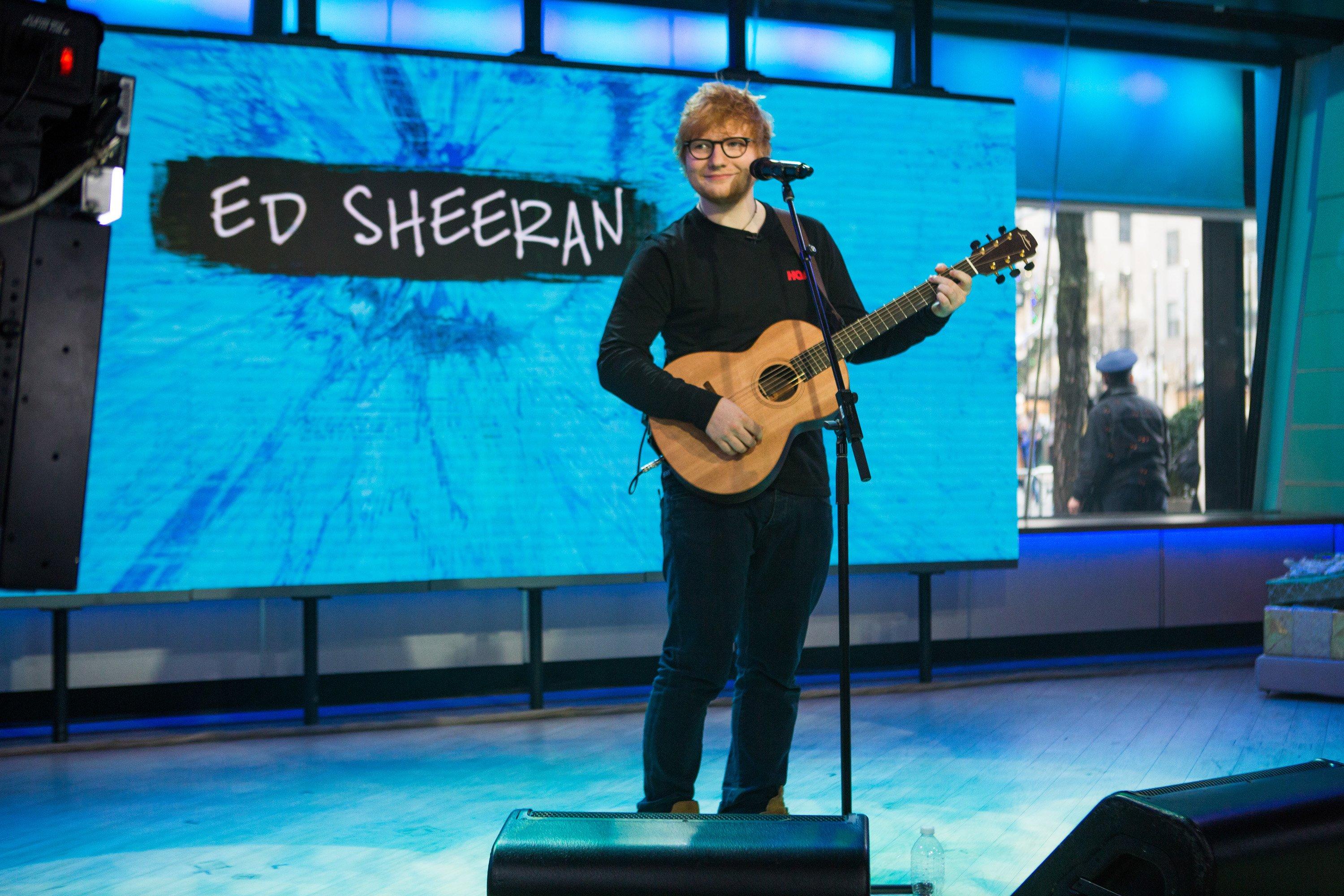

Ed Sheeran

Photo: Nathan Congleton/NBC/NBCU/Getty Images

feature

What Makes The Ultimate Love Song?

Whether it's "Shape Of You," "You Belong With Me," "I Will Always Love You," "Un-Break My Heart," or "Earth Angel," go inside the anatomy of a great love song

The Beatles proclaimed that it was all you needed. Whitney Houston sang that she'd found the greatest of all. Kendrick Lamar rapped that it made him feel as powerful as Mike Tyson. And Bruno Mars insists that it's best served with strawberry champagne on ice.

The element in question is, of course, love — an emotion potent enough to have inspired all manner of singers and songwriters for centuries. Words of love were set to music by the poets of ancient Greece and Rome, and passionate desire was a popular topic for medieval troubadours. The earliest example of a recorded voice is an 1860 phonautograph recording of "Au Clair De Lune," a traditional French folk song that is arguably about a late-night romantic encounter.

Whether spoken or sung, "I love you" would seem to be a fairly straightforward statement, but the feelings and circumstances behind those words can be complicated, which would explain why love songs come in an uncanny number of varieties.

There are songs for brand-new love (Ed Sheeran's "Shape Of You"); love that's stood the test of time (George Gershwin's much-covered "Our Love Is Here To Stay"); breakup songs (Taylor Swift's "We Are Never Getting Back Together"); make-up songs (Peaches And Herb's "Reunited"); songs that express love as something selfless and noble (Dolly Parton's "I Will Always Love You") and songs that express love as something a little more physical (Marvin Gaye's "Sexual Healing").

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/JGwWNGJdvx8" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Love has clearly served as a well-tapped source of inspiration, but not all loves — and not all loves songs — are equal. While some love songs endure as classics — happily danced to at generations of weddings — plenty of others fade as quickly as a bad first date. Just a few bars of the best love songs can make hearts swell and eyes tear up, while other more-syrupy contenders induce cringes of horror or shrugs of indifference.

So, what is it that makes a great love song great?

"What makes a love song great is what makes any song great — you have to feel it, " says Diane Warren, a GRAMMY-winning songwriter who has added to the love song canon with such hits as "Because You Loved Me," sung by Celine Dion, "Un-Break My Heart, " sung by Toni Braxton, "There You'll Be," sung by Faith Hill, and the Cher No. 1 single "If I Could Turn Back Time."

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/p2Rch6WvPJE" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"I think a great love song obviously has to have great lyrics and great content," says GRAMMY nominee Thomas Rhett, writer of romantic ditties such as "Sweetheart." "But I think sometimes, above that, melody is what attracts people."

"[A] perfect melody is always good because it allows you to dance to something that you've never felt before," says Anthony Hamilton, whose love song catalog includes "So In Love" with fellow GRAMMY winner Jill Scott. "Great lyrics and the perfect vocal tone [are also] very important."

"The best love songs are something that someone hears and it instantly becomes theirs," Warren adds. "Listeners might have their own unique experience of why a certain song means something to them, but if it's meaningful enough it becomes a part of their own personal soundtrack. In a way, a love song is a canvas that you paint yourself onto, and when a truly great love song comes along, everybody feels they can paint themselves onto it. It becomes a part of everybody's inner life."

"It's writing about something that everybody can relate to but looking at it at a slightly different angle," says Shelly Peiken, a GRAMMY-nominated songwriter who has collaborated with Britney Spears, Keith Urban and Celine Dion, among others. "So when your audience hears it, they go, 'I know how that feels and I never thought about it that way.'"

Perhaps no one has had more experience playing personal soundtracks in public than disc jockey Art Laboe, who is currently in his 74th year as an on-air personality. His syndicated program, "The Art Laboe Connection," regularly mixes love songs from every decade since the '50s, and a long-time signature feature of Laboe's program has been the listener dedications he reads as song intros. Laboe agrees that the most powerful and popular love songs have always had a way of connecting with listeners in a uniquely intimate way.

"The one thing that's been true through the decades that I've been on is that the great love songs feel personal to each listener," says Laboe. "I don't think there's any one way to make that happen, because musically and lyrically love songs can come from all sorts of directions. But with the ones that really work there's something in them that moves a person beyond the actual melody or the vocalist's performance or the quality of the production, and the big songs that really last continue to move people in that personal way."

As evidence of just how lasting a love song can be, Laboe cites the fact that he still receives weekly requests for "Earth Angel," a No. 1 hit for the doo-wop group the Penguins back in 1955. He points to a more contemporary artist — Swift — to explain how an artist's personal, musical expression can connect with the public at-large.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/vSSdBD-Mae4" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"She's a talented writer who can come up with something like 'You Belong With Me,'" says Laboe. "That song goes sailing out there and smacks right into the bulls-eye of what a lot of people are feeling, or have felt, or can relate to. Just about everybody — man or woman — has had the experience of looking at somebody else you're interested in and thinking what the song is saying. So Taylor Swift may have been writing about something very specific and personal to her, but she ended up with a song that millions and millions of people felt personally connected to in their own way."

"A very important ingredient in a love song is pain," adds GRAMMY winner Gillian Welch. "Because even when love is good and true, there's part of it that's painful."

Emotional considerations aside, the writing of a love song requires craft and technical skill. But Warren says her best work can't simply be summoned through craft alone — it comes when she feels as moved at the beginning of the creative process as a listener might be by the finished recording.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/VuNIsY6JdUw" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"On a technical level, every song is an individual and what works for one song might not work for another," she says. "Sometimes I'll start writing with a title in mind, or have some chords to work with. Sometimes I've got a basic concept for a song. But the main thing is that I have to feel something as I'm writing it. If I don't feel something, that song isn't going to be great. And if it seems like more of an exercise than a real expression of emotion, I'm probably not even going to finish writing it. But if I feel moved just getting to work on something, then there's a good chance it's going to move somebody else too."

Love songs — even the great ones — can become so familiar that it may be easy to underestimate their effect on both individuals and entire cultures. But at least one historian with a keen understanding of the evolution of love songs contends that their power to move, and the specific way they get people to move, should not be dismissed.

"What makes a love song great is what makes any song great — you have to feel it." — Diane Warren

"People are wrong to view these songs as mere entertainment or escapism," says Ted Gioia, author of Love Songs: The Hidden History. "The purpose of a successful love song is to create love. The first love songs were part of fertility rites and they aimed at changing the world, not just describing it. When the Beatles sang 'All You Need Is Love' or John Coltrane performed A Love Supreme, they wanted to transform the world in which they lived. And on a personal level, many of us would not be here today if our parents hadn't heard a love song at the right time and place. Those love songs aren't just life-changing, they are life-creating."

Catching Up On Music News By The Recording Academy Just Got Easier. Have A Google Home Device? "Talk To GRAMMYs"

(Chuck Crisafulli is an L.A.-based journalist and author whose most recent works include Go To Hell: A Heated History Of The Underworld, Me And A Guy Named Elvis, Elvis: My Best Man, and Running With The Champ: My Forty-Year Friendship With Muhammad Ali.)