PHOTO: Jeff Kravitz / Contributor

news

Arooj Aftab's "Mohabbat" Wins Best Global Music Performance | 2022 GRAMMYs

Arooj Aftab's "Mohabbat" wins Best Global Music Performance at the 2022 GRAMMYs. Aftab is the first Pakistani woman to win a GRAMMY and is also nominated for Best New Artist.

Arooj Aftab won the GRAMMY for Best Global Music Performance for "Mohabbat" at the 2022 GRAMMYs; she is the first artist to win in the new category. This is the composer’s first GRAMMY win of the 2022 GRAMMYs, and of their career. Aftab, who is the first Pakistani woman to be nominated for a GRAMMY, is also up for Best New Artist.

"I feel like this category in of itself has been insane… it should this be called yacht party category,” Aftab said onstage at the 64th GRAMMY Awards. “I made [this record] about everything that broke me and put me back together. Thank you for listening to it and making it yours."

Angelique Kidjo and Burna Boy, Femi Kuti, Yo-Yo Ma with Angelique Kidjo, and Wizkid ft. Tems were the other nominees in the prestigious category.

Check out the complete list of winners and nominees at the 2022 GRAMMYs.

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic via Getty Images

list

New Music Friday: Listen To New Albums & Songs From Eminem, Maya Hawke, ATEEZ & More

Dive into the weekend with music that’ll make you dance, brood and think — by Jessie Reyez, Ayra Starr, Adam Lambert, and many more.

After the cookouts and kickbacks of Memorial Day weekend, getting through the workweek is never easy. But you made it through — and now it's time for another weekend of however you decompress. As always, killer jams and musical food for thought have arrived down the pipeline.

As you freshen up your late-spring playlist, don't miss these offerings by artists across generations, moods, genres, and vibes — from K-pop to classic country and beyond.

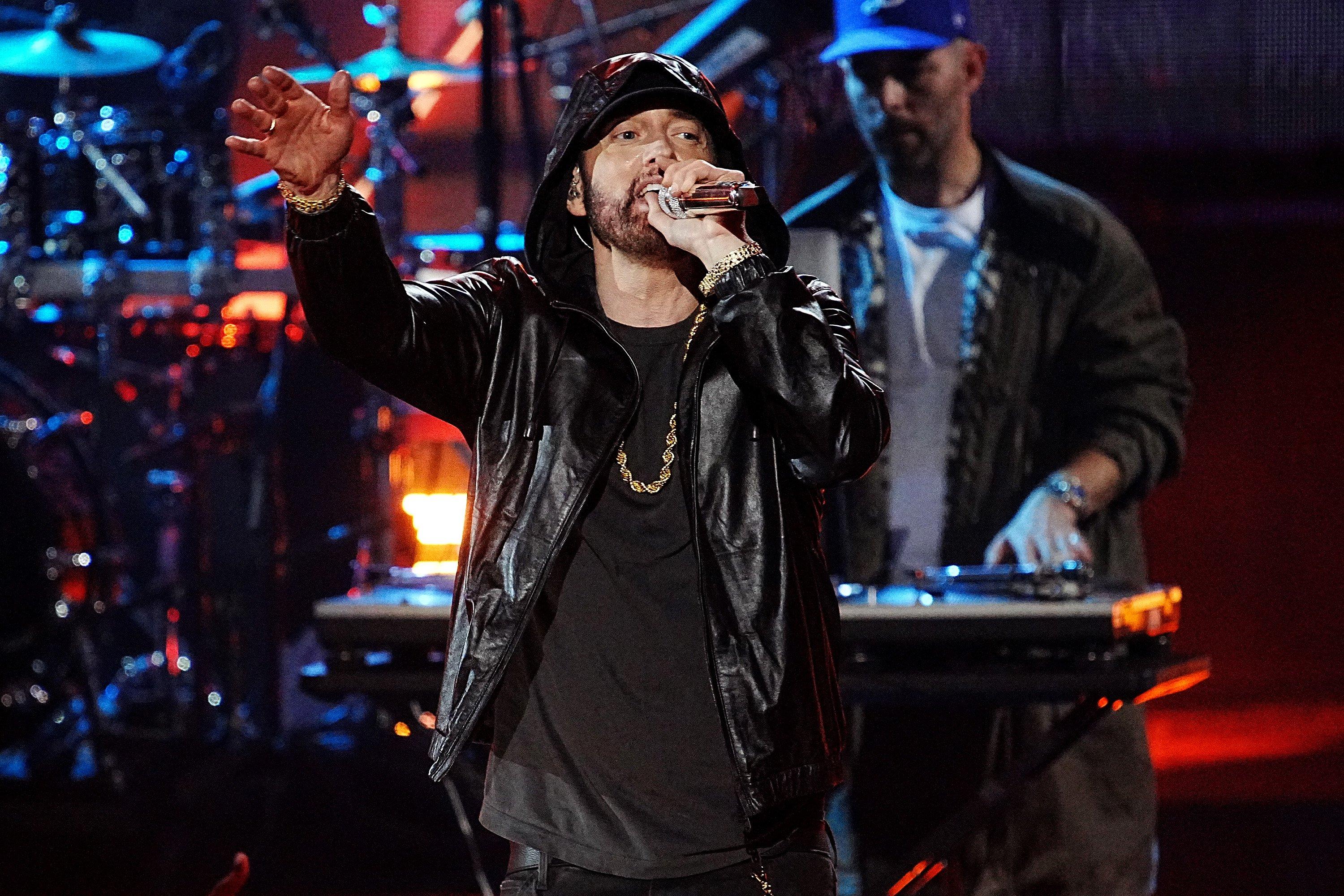

Eminem — "Houdini"

It looks like Dua Lipa isn't the only artist to name-drop Erik Weisz this year. In a recent Instagram video with magician David Blaine, Eminem hinted at a major career move, quipping, "For my last trick, I'm going to make my career disappear," as Blaine casually noshed on a broken wineglass.

With Em's next album titled The Death of Slim Shady, fans were left in a frenzy — was he putting the mic down for good? If "Houdini" is in fact part of Eminem's final act, it seems he'll be paying homage to his career along the way: the song includes snippets of Em classics "Without Me," "The Real Slim Shady," "Just Lose It" and "My Name Is."

The superhero comic-themed video also calls back to some of the rapper's iconic moments, including the "Without Me" visual and his 2000 MTV Video Music Awards performance. It also features cameos from the likes of Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, 50 Cent, and Pete Davidson — making for a star-studded thrill ride of a beginning to what may be his end.

Read More: Is Eminem's “Stan” Based On A True Story? 10 Facts You Didn't Know About The GRAMMY-Winning Rapper

Maya Hawke — 'Chaos Angel'

"What the Chaos Angel is to me," Maya Hawke explained in a recent Instagram video, "is an angel that was raised in heaven to believe they're the angel of love, then sent down to do loving duties."

Chaos Angel, the third album by Maya Hawke, out via Mom+Pop Records, is an alt-rock treasure with a psychologically penetrating bent. Smoldering tracks like "Dark" and "Missing Out" plumb themes of betrayal and bedlam masterfully.

Jessie Reyez & Big Sean — "Shut Up"

Before May 31, Jessie Reyez's 2024 releases have come in the form of airy contributions for Bob Marley: One Love and Rebel Moon. And for the first release of her own, she's bringing the heat.

Teaming up with fellow rapper Big Sean for "Shut Up," Reyez delivers some fiery lines on the thumping track: "They b—es plastic, that b— is a catfish, oh-so dramatic/ And I'm sittin' pretty with my little-ass t—es winnin' pageants." Big Sean throws down, too: "B—, better read the room like you telepromptin'/ And watch how you speak to a n—a 'cause I'm not them."

Foster the People — "Lost In Space"

Indie dance-pop favorites Foster The People — yes, of the once-inescapable "Pumped Up Kicks" fame — are back with their first new music since 2017's Sacred Hearts Club. The teaser for their future-forward, disco-powered new song, "Lost in Space," brings a psychedelic riot of colors to your eyeballs.

The song is equally as trippy. Over a swirling, disco-tinged techno beat, the group bring their signature echoing vocals to the funky track, which feels like the soundtrack to an '80s adventure flick.

"Lost in Space" is the first taste of Foster The People's forthcoming fourth studio album, Paradise State of Mind, which will arrive Aug. 16. If the lead single is any indication — along with frontman Mark Foster's tease that the album started "as a case study of the late Seventies crossover between disco, funk, gospel, jazz, and all those sounds" — fans are in for quite the psychedelic ride.

Arooj Aftab — 'Night Reign'

Arooj Aftab landed on the scene with the exquisitely blue Vulture Prince, which bridged modern jazz and folk idioms with what she calls "heritage material" from Pakistan and South Asia. The album's pandemic-era success threatened to box her in, though; Aftab is a funny, well-rounded cat who's crazy about pop music, too. Crucially, the guest-stuffed Night Reign shows many more sides of this GRAMMY-winning artist — her sound is still instantly recognizable, but has a more iridescent tint — a well-roundedness. By the strength of songs like "Raat Ki Rani" and "Whiskey," and the patina of guests like Moor Mother and Vijay Iyer, this Reign is for the long haul.

Learn More: Arooj Aftab, Vijay Iyer & Shahzad Ismaily On New Album Love In Exile, Improvisation Versus Co-Construction And The Primacy Of The Pulse

Willie Nelson — 'The Border'

By some counts, Willie Nelson has released more than 150 albums — try and let that soak in. The Red Headed Stranger tends to crank out a Buddy Cannon-produced album or two per year in his autumn years, each with a slight conceptual tilt: bluegrass, family matters, tributes to Harlan Howard or the Great American Songbook. Earthy, muted The Border is another helping of the good stuff — this time homing in on songwriters like Rodney Crowell ("The Border"), Shawn Camp ("Made in Texas") and Mike Reid ("Nobody Knows Me Like You.") Elsewhere, Nelson-Cannon originals like "What If I'm Out of My Mind" and "How Much Does It Cost" fold it all into the 12-time GRAMMY winner's manifold musical universe.

ATEEZ — 'GOLDEN HOUR : Part.1'

South Korean boy band ATEEZ last released new material with late 2023's The World EP.Fin: Will. Now, they're bringing the K-pop fire once again with their 10th mini-album, GOLDEN HOUR Part.1.

Released in a rainbow of physical editions, the release was teased by a short clip for "WORK," where ATEEZ pans for gold like old prospectors in an off-kilter desert scene, then proceeds to throw the mother of all parties. As for the rest of GOLDEN HOUR, they bring flavors of reggaeton ("Blind), wavy R&B ("Empty Box") and reggae ("Shaboom") — further displaying their versatility as a group, and setting an exciting stage for Part.2.

Learn More: Inside The GRAMMY Museum's ATEEZ & Xikers Pop-Up: 5 Things We Learned

Ayra Starr — 'The Year I Turned 21'

Beninese-Nigerian singer and GRAMMY nominee for Best African Music Performance Ayra Starr pays homage to the big two-one with her second album, The Year I Turned 21, which she's been teasing all month. We've seen the crimson, windswept cover art; we've soaked up the 14 track titles, which reveal collaborations with the likes of ASAKE, Anitta, Coco Jones, and Giveon. Now, after small tastes in singles "Commas,""Rhythm & Blues" and "Santa" (with Rvssian and Rauw Alejandro), we can behold what the "Rush" star has called "excellent, sonically amazing" and "unique, because I've been evolving sonically."

Watch: Ayra Starr’s Most Essential “Item” On The Road Is Her Brother | Herbal Tea & White Sofas

Adam Lambert — "LUBE" & "WET DREAM"

The "American Idol" and Queen + Adam Lambert star is turning heads — for very good reason. He's going to release AFTERS, a new EP of house music and an unflinching exploration of queerness and sex-positivity. "I throw many house parties and my aim was to create a soundtrack inspired by wild nights, giving a voice to our communities' hedonistic desires and exploits," Lambert explained in a press release.

The first two singles, "LUBE" and "WET DREAM," achieve exactly that. From the pulsing beat of "LUBE" (along with the "Move your body like I do" demand of the chorus) to the racing melody of "WET DREAM," it's clear AFTERS will bring listeners straight to a sweaty dance floor — right where Lambert wants them.

Wallows Talk New Album Model, "Entering Uncharted Territory" With World Tour & That Unexpected Sabrina Carpenter Cover

Photo: Williams Peters

interview

Meet Usher Collaborator Pheelz, The Nigerian Producer & Singer Who Wants You To 'Pheelz Good'

After working with Usher on two tracks for his latest album, 'Coming Home,' Lagos' Pheelz is looking inward. His new EP, 'Pheelz Good II' drops May 10 and promises to be an embrace of the artist's unabashed self.

If you were online during the summer of 2022, chances are you’ve heard Pheelz’s viral hit single "Finesse." The swanky Afro-fusion track (featuring fellow Nigerian artist Bnxn) ushered in a world of crossover success for Pheelz, who began his career as a producer for the likes of Omah Lay, Davido, and Fireboy DML.

Born Phillip Kayode Moses, Pheelz’s religious upbringing in Lagos state contributed to his development as a musician. He manned the choir at his father’s church while actively working on his solo music. Those solo efforts garnered praise from his peers and music executives, culminating in Pheelz's debut EP in 2021. Hear Me Out saw Pheelz fully embrace his talent as a vocalist, songwriter, and producer.

"I feel important, like I’m just molding clay, and I have control over each decision," Pheelz tells GRAMMY.com about creating his own music.

2022 saw the release of the first two tapes in his Pheelz Good trilogy: Pheelz Good I and Pheelz Good (Triibe Tape), which was almost entirely self-produced. The 29-year-old's consistency has paid off: he produced and sang on Usher’s "Ruin," the lead single from his latest album Coming Home, and also produced the album's title track featuring Burna Boy. But Pheelz isn't only about racking up big-name collaborators; the self-proclaimed African rockstar's forthcoming projects will center on profound vulnerability and interpersonal honesty. First up: Pheelz Good II EP, out May 10, followed by a studio album in late summer.

Both releases will see the multi-hyphenate "being unapologetically myself," Pheelz tells GRAMMY.com. "It will also be me being as vulnerable as I can be. And it’s going to be me embracing my "crayge" [crazy rage]...being myself, and allowing my people to gravitate towards me."

Ahead of his new project, Pheelz spoke with GRAMMY.com about his transition from producer artist, designing all his own 3D cover art, his rockstar aesthetic, and what listeners can expect from Pheelz Good II.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What sparked your transition from singing in church to realizing your passion for creating music?

For me, it wasn’t really a transition. I just always loved making music so for me I felt like it was just wherever I go to make music, that’s where I wanna be. I would be in church and I was the choirmaster at some point in my life, so I would write songs for Sunday service as well. And then I would go to school as well and write in school, and people heard me and they would love it. And I would want to do more of that as well.

A friend of my dad played some of my records for the biggest producers in Nigeria back then and took me on as an intern in his studio. I guess that’s the transition from church music into the industry. My brothers and sisters were in the choir, but that came with the job of being the children of the pastor, I guess. None of them really did music like me; I’m the only one who took music as a career and pursued it.

You made a name for yourself as a producer before ever releasing your music, earning Producer Of The Year at Nigeria’s Headies Awards numerous times. What finally pushed you to get into the booth?

I’ve always wanted to get into the booth. The reason why I actually started producing was to produce beats for songs that I had written. I’ve always been in the booth, but always had something holding me back. Like a kind of subconscious feeling over what my childhood has been. I wasn’t really outspoken as a child growing up, so I wouldn’t want people to really hear me and would shy away from the camera in a sense. I think that stuck with me and held me back.

But then COVID happened and then I caught COVID and I’m like Oh my god and like that [snaps fingers] What I am doing? Why am I not going full steam? Like why do I have all this amazing awesomeness inside of me and no one gets to it because I’m scared of this or that?

There was this phrase that kept ringing in my head: You have to die empty. You can’t leave this earth with all of this gift that God has given you; you have to make sure you empty yourself. And since then, it’s just been back-to-back, which just gave me the courage.

How did you react to " Finesse" in former President Barack Obama’s annual summer playlist in 2022?

Bro, I reacted crazy but my dad went bananas. [Laughs.] I was really grateful for that moment, but just watching my dad react like that to that experience was the highlight of that moment for me. He's such a fan of Barack Obama and to see that his son’s music is on the playlist, it just made his whole month. Literally. He still talks about it to this day.

Experiences like that just make me feel very grateful to be here. Life has really been a movie, just watching a movie and just watching God work and being grateful for everything.

At first he [my dad] [didn’t support my career] because every parent wants their child to be a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer. But when he saw the hunger [I have], and I was stubborn with [wanting] to do music, he just had to let me do it. And now he’s my number one fan.

Your latest single, "Go Low" arrived just in time for festival season. What was it like exploring the live elements of your art at SXSW and your headlining show in London at the end of April?

I have always wanted to perform live. I’ve always loved performing; Pheelz on stage is the best Pheelz. Coming from church every Sunday, I would perform, lead prayers and worship, so I’ve always wanted to experience that again.

Having to perform live with my band around the world is incredible man. And I’ll forever raise the flag of amazing Afro live music because there’s a difference, you know? [Laughs.] There are so many elements and so many rhythms and so many grooves

I’ve noticed that much of your recent cover art for your singles and EPs is animated or digitally crafted. What’s the significance, if any, of this stylistic choice?

It still goes back to my childhood because I wasn’t expressive as a child; I wouldn’t really talk or say how I felt. I’d rather write about it, write a song about it, write a poem about it, or draw about it. I’d draw this mask and then put how I’m feeling into that character, so if I was angry, the mask would be raging and just angry.

The angry ones were the best ones, so that stuck with me even after I started coming out of my shell and talking and being expressive; that act of drawing a mask still stuck with me. And then I got into 3D, and I made a 3D version of the mask and I made a 3D character of the mask. So I made that the main character, and then I just started making my lyric videos, again post-COVID, and making them [lyric videos] to the characters and making the actual video mine as well.

In the future, I’m gonna get into fashion with the characters, I’m gonna get into animation and cartoons and video games, but I just wanna take it one step at a time with the music first. So, in all of my lyric videos, you get to experience the characters. There’s a fight [scene] among them in one of the lyric videos called "Ewele"; there is the lover boy in the lyric video for "Stand by You"; there are the bad boys in the lyric video for "Balling." They all have their own different characters so hopefully in the near future, I will get to make a feature film with them and just tell their story [and] build a world with them. I make sure I put extra energy into that, make most of them myself so the imprint of my energy is gonna be on it as well because it’s very important to me.

You and Usher have a lengthy working relationship. You first performed together in 2022 at the Global Citizen Festival, then produced/co-wrote "Coming Home" and "Ruin." Take us through the journey of how you two began collaborating.

It started through a meeting with [Epic Records CEO] L.A. Reid; he was telling me about the album that they were working on for Usher and I’m like, "Get me into the studio and lemme see what I can cook up." And they got me into the studio, [with Warner Records A&R] Marc Byers, and I wrote and produced "Coming Home." I already had "Ruin" a year before that.

["Ruin"] was inspired by a breakup I just went through. Some of the greatest art comes from pain, I guess. That record was gonna be for my album but after I came home I saw how L.A. Reid and Usher reacted and how they loved it. I told them, "I have this other song, and I think you guys would like it for this album." And I played "Ruin," and the rest was history.

Before your upcoming EP, you’ve worked with Pharrell Williams, Kail Uchis, and the Chainsmokers in the studio. What do you consider when selecting potential collaborators?

To be honest, I did not look for these collabs. It was like life just brought them my way, because for me I’m open to any experience. I’m open to life; I do it the best I can at any moment, you understand?

Having worked with Pharrell now, Dr. Dre, Timbaland, and the Chainsmokers, I’m still shocked at the fact that this is happening. But ultimately, I am grateful for the fact that this is happening. I am proud of myself as well for how far I’ve come. Someone like Timbaland — they are literally the reason why I started producing music; I would literally copy their beats, and try to sound like them growing up.

[Now] I have them in the same room talking, and we’re teaching and learning, making music and feeding off of each others’ energy. It’s a dream come true, literally.

What's it like working with am electro-pop group like the Chainsmokers? How’d you keep your musical authenticity on "PTSD"?

That experiment ["PTSD"] was actually something I would play with back home. But the crazy thing is, it’s gonna be on the album now, not the EP. I would play it back home, like just trying to get the EDM and Afrohouse world to connect, cause I get in my Albert Einstein bag sometimes and just try and experiment. So when I met the Chainsmokers and like. "Okay, this is an opportunity to actually do it now," and we had a very lengthy conversation.

We bonded first as friends before we went into the studio. We had an amazing conversation talking about music, [them] talking about pop and electronic music, and me talking about African music. So it was just a bunch of producers geeking out on what they love to do. And then we just talk through how we think the sound would be like really technical terms. Then we get into the studio and just bang it out. Hopefully, we get to make some more music because I think we can create something for the world together.

I’ve noticed you dress a bit eccentrically. Have you always had this aesthetic?

I’ve always dabbled in fashion. Even growing up, I would sketch for my sister and make this little clothing, so like I would kick up my uniform as well, make it baggy, make it flare pants, make it fly.

I think that stuck with me until now, trying different things with fashion. And now I have like stylists I can talk to and throw ideas off of and create something together. So yeah, I want to get into the fashion space and see what the world has in store for me.

What can fans expect as you’re putting the finishing touches on your upcoming EP Pheelz Good II and your album?

Pheelz Good II, [will be] a close to the Pheelz Good trilogy of Pheelz Good I, Pheelz Good Triibe Tape and Pheelz Good II. The album is going to be me being unapologetically myself still. But it will also be me being as vulnerable as I can be.

It’s going to be me embracing my crayge [crazy rage]. Like just embracing me unapologetically and being me, being myself, and allowing my people to gravitate towards me, you get me. But I’m working on some really amazing music that I am so proud of. I’m so proud of the EP and the album.

Mr. Eazi’s Gallery: How The Afrobeats Star Brought His Long-Awaited Album To Life With African Art

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?: Autumn Rowe Revisits Her Unexpected Album Of The Year Win With Jon Batiste

Acclaimed songwriter Autumn Rowe reveals the inspirational location where her Album Of The Year golden gramophone resides, and details the "really funny way" she first met Jon Batiste.

Ever since Autumn Rowe won a GRAMMY in 2022, it's been her biggest motivation. That's why the musical multi-hyphenate keeps the award nestled in her writing room — to keep her creative juices flowing.

"It reminds me that anything is possible," she says in the latest episode of Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?

Rowe won her first-ever career GRAMMY in 2022 with an Album Of The Year award for Jon Batiste's We Are. "It was very stressful," she recalls with a laugh.

"Right before they announced Album Of The Year, the pressure started getting to me," Rowe explains. "Album Of The Year is the biggest possible award you can win. So, I'm like, 'We didn't win any of these [categories], how are we going to win the biggest award?"

The win also taught her one unforgettable, valuable lesson: "We matter. The music matters. Everything matters. We just have to create it. If there isn't space for it, we have to make space for it. Don't wait for something to open."

Rowe says she grew up "super dirt poor" and never even had the opportunity to watch the awards ceremony on television. "To be a GRAMMY winner means it is possible for everyone," she declares.

Press play on the video above to learn more about the backstory of Autumn Rowe's Album Of The Year award, and remember to check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?

Photo: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Doja Cat & SZA Tearfully Accept Their First GRAMMYs For "Kiss Me More"

Relive the moment the pair's hit "Kiss Me More" took home Best Pop Duo/Group Performance, which marked the first GRAMMY win of their careers.

As Doja Cat put it herself, the 2022 GRAMMYs were a "big deal" for her and SZA.

Doja Cat walked in with eight nominations, while SZA entered the ceremony with five. Three of those respective nods were for their 2021 smash "Kiss Me More," which ultimately helped the superstars win their first GRAMMYs.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, revisit the night SZA and Doja Cat accepted the golden gramophone for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance — a milestone moment that Doja Cat almost missed.

"Listen. I have never taken such a fast piss in my whole life," Doja Cat quipped after beelining to the stage. "Thank you to everybody — my family, my team. I wouldn't be here without you, and I wouldn't be here without my fans."

Before passing the mic to SZA, Doja also gave a message of appreciation to the "Kill Bill" singer: "You are everything to me. You are incredible. You are the epitome of talent. You're a lyricist. You're everything."

SZA began listing her praises for her mother, God, her supporters, and, of course, Doja Cat. "I love you! Thank you, Doja. I'm glad you made it back in time!" she teased.

"I like to downplay a lot of s— but this is a big deal," Doja tearfully concluded. "Thank you, everybody."

Press play on the video above to hear Doja Cat and SZA's complete acceptance speech for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance at the 2022 GRAMMY Awards, and check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind.

How 'SOS' Transformed SZA Into A Superstar & Solidified Her As The Vulnerability Queen