Photo: Terry O'Neill/Getty Images

Mick Ronson

news

What Was Life Like Beside Bowie? New Doc On Guitarist Mick Ronson

Guitar great and David Bowie's early '70s musical partner is the subject of a new documentary out this fall

As of late, more and more compelling music documentaries have been unearthing the stories behind the eras and albums we love. This fall, glam-rock guitar great Mick Ronson's story gets its own rock doc.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/d1BxmWVr-lc" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Behind Bowie: The Mick Ronson Story follows Ronson's prolific career from his work with David Bowie as guitarist in the Spiders From Mars to his work with Lou Reed on his 1972 classic album, Transformer, and then with Bob Dylan as part of the Rolling Thunder Review live band in 1975–1976.

"I spent a little time with David [Bowie]," Queen drummer Roger Taylor says in the trailer, "and he used to say when I found Mick Ronson, I found my Jeff Beck."

Ronson's untimely death in 1993 at age 46 came far too soon, and Bowie said of his musical sideman, "If Mick had lived on, he would have become a major producer and arranger, and of course, he would have remained one of rock's great guitar players."

The film hits select theaters Sept. 1 and home video Oct. 27.

Read More: James Murphy On Advice From David Bowie, Being "Done" With Producing

Photo: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Live Nation

list

10 Record Store Day 2024 Releases We're Excited About: The Beatles, Notorious B.I.G. & More

In honor of Record Store Day 2024, which falls on April 20, learn about 10 limited, exclusive drops to watch out for when browsing your local participating record store.

From vinyl records by the 1975 and U2, to album reissues and previously unreleased music, record stores around the world are stocking limited and exclusive releases for Record Store Day 2024.

The first Record Store Day kicked off in 2008 and every year since, the event supporting independently owned record stores has grown exponentially. On Record Store Day 2024, which falls on April 20, there will be more than 300 special releases available from artists as diverse as the Beatles and Buena Vista Social Club.

In honor of Record Store Day 2024 on April 20, here are 10 limited and exclusive drops to watch out for when browsing your local participating record store.

David Bowie — Waiting in the Sky (Before The Starman Came To Earth

British glam rocker David Bowie was a starman and an icon. Throughout his career, he won five GRAMMY Awards and was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006.

On RSD 2024, Bowie's estate is dialing it back to his Ziggy Stardust days to make Waiting in the Sky (Before The Starman Came To Earth) available for the first time. The record features recordings of Bowie's sessions at Trident Studios in 1971, and many songs from those sessions would be polished for his 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

The tracklisting for Waiting in the Sky differs from Ziggy Stardust and features four songs that didn’t make the final album.

Talking Heads — Live at WCOZ 77

New York City-based outfit Talking Heads defined the sound of new wave in the late '70s and into the next decade. For their massive influence, the group received two GRAMMY nominations and was later honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2021.

While promoting their debut album Talking Heads: 77, the quartet recorded a live performance for the New Albany, Pennsylvania radio station WCOZ in 1977. The Live at WCOZ 77 LP will include 14 songs from that performance at Northern Studios, including seven that will be released for the first time. Among the previously unheard cuts are "Love Goes To A Building On Fire" and "Uh-Oh, Love Comes To Town." During that session, Talking Heads also performed songs like "Psycho Killer" and "Pulled Up."

The Doors — Live at Konserthuset, Stockholm, September 20, 1968

The Doors were at the forefront of the psychedelic rock movement of the 1960s and early '70s. One of Jim Morrison's most epic performances with the band will be available on vinyl for the first time.

Live at Konserthuset, Stockholm, September 20, 1968 includes recordings from a radio broadcast that was never commercially released. The 3-LP release includes performances of songs from the Doors’ first three albums, including 1967’s self-titled and Strange Days. In addition to performing their classics like "Light My Fire" and "You're Lost Little Girl," the Doors and Morrison also covered "Mack the Knife" and Barret Strong's "Money (That's What I Want)" live during this session.

Dwight Yoakam — The Beginning And Then Some: The Albums of the '80s

Over the course of his 40-year career, country music icon Dwight Yoakam has received 18 GRAMMY nominations and won two golden gramophones for Best Male Country Vocal Performance in 1994 and Best Country Collaboration with Vocals in 2000.

On Record Store Day 2024, Yoakam will celebrate the first chapter of his legacy with a new box set: The Beginning And Then Some: The Albums of the '80s. His debut album Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. and 1987’s Hillbilly Deluxe will be included in the collection alongside exclusive disc full of rarities and demos. The 4-LP set includes his classics like "Honky Tonk Man," "Little Ways," and "Streets of Bakersfield." The box set will also be available to purchase on CD.

The Beatles — The Beatles Limited Edition RSD3 Turntable

Beatlemania swept across the U.S. following the Beatles’ first appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" in February 1964, setting the stage for the British Invasion. With The Beatles Limited Edition RSD3 Turntable, the band will celebrate their iconic run of appearances on Sullivan’s TV program throughout that year.

The box set will include a Beatles-styled turntable and four 3-inch records. Among those records are the hits "I Want To Hold Your Hand," "Till There Was You," "She Loves You," and "I Saw Her Standing There," which the Beatles performed on Sullivan's TV across several appearances.

Among 23 GRAMMY nominations, the Beatles won seven golden gramophones. In 2014, the Recording Academy honored them with the Lifetime Achievement Award.

Olivia Rodrigo and Noah Kahan — From The BBC Radio 1 Live Lounge LP

Olivia Rodrigo and Noah Kahan are two of the biggest pop stars in the world right now — Rodrigo hitting the stage with No Doubt at Coachella and near the end of her global GUTS Tour; Kahan fresh off a Best New Artist nomination at the 2024 GRAMMYs. Now, they're teaming up for the split single From The BBC Radio 1 Live Lounge LP, a release culled from each artist's "BBC Radio 1 Live Lounge" sessions.

The special vinyl release will include Rodrigo's live cover of Kahan's breakout hit "Stick Season." The single also includes Kahan’s cover of Rodrigo’s song "Lacy" from her second album, GUTS. This month, they performed the song live together on Rodrigo’s Guts World Tour stop in Madison Square Garden.

Buena Vista Social Club — Buena Vista Social Club

Influential Cuban group Buena Vista Social Club popularized genres and sounds from their country, including son cubano, bolero, guajira, and danzón. Buena Vista Social Club's landmark self-titled LP won the GRAMMY for Best Tropical Latin Album in 1998.

The following year, a documentary was released that captured two of the band's live performances in New York City and Amsterdam. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the documentary, the Buena Vista Social Club album will be released on a limited edition gold vinyl with remastered audio and bonus tracks.

Buena Vista Social Club is one of the 10 recordings to be newly inducted into the GRAMMY Hall Of Fame as part of the 2024 inductee class.

Danny Ocean — 54+1

Venezuelan reggaeton star Danny Ocean broke through on a global level in 2016 with his self-produced debut single "Me Rehúso," a heartbreaking track inspired by Ocean fleeing Venezuela due to the country's economic instability and the lover he had left behind.

With "Me Rehúso," Ocean became the first solo Latin artist to surpass one billion streams on Spotify, on the platform with a single song. "Me Rehúso" was included on his 2019 debut album 54+1, which will be released on vinyl for the first time for Record Store Day.

Lee "Scratch" Perry & The Upsetters — Skanking With The Upsetter

Jamaican producer Lee "Scratch" Perry pioneered dub music in the 1960s and '70s. Perry received five GRAMMY nominations in his lifetime, including winning Best Reggae Album in 2003 for Jamaican E.T.

To celebrate the legacy of Perry's earliest dub recordings, a limited edition run of his 2004 album Skanking With The Upsetter will be released on Record Store Day. His joint LP with his house band the Upsetters will be pressed on transparent yellow vinyl. Among the rare dub tracks on the album are "Bucky Skank," "Seven & Three Quarters (Skank)," and "IPA Skank."

Notorious B.I.G. — Ready To Die: The Instrumentals

The Notorious B.I.G. helped define the sound of East Coast rap in the '90s. Though he was tragically murdered in 1997, his legacy continues to live on through his two albums.

During his lifetime, the Notorious B.I.G. dropped his 1994 debut album Ready to Die, which is widely considered to be one of the greatest hip-hop releases of all-time. In honor of the 30th anniversary of the album (originally released in September '94), his estate will release Ready To Die: The Instrumentals. The limited edition vinyl will include select cuts from the LP like his hits "Big Poppa," "One More Chance/Stay With Me," and "Juicy." The album helped him garner his first GRAMMY nomination in 1996 for Best Rap Solo Performance. The Notorious B.I.G. received an additional three nominations after his death in 1998.

10 Smaller Music Festivals Happening In 2024: La Onda, Pitchfork Music Fest, Cruel World & More

list

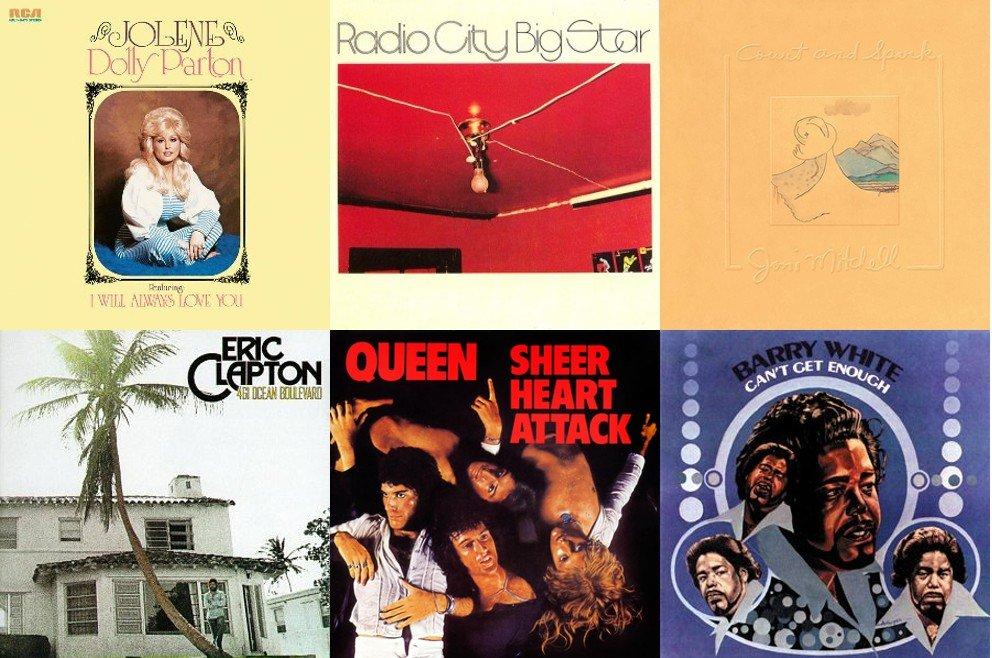

21 Albums Turning 50 In 2024: 'Diamond Dogs,' 'Jolene,' 'Natty Dread' & More

Dozens of albums were released in 1974 and, 50 years later, continue to stand the test of time. GRAMMY.com reflects on 21 records that demand another look and are guaranteed to hook first-time listeners.

Despite claims by surveyed CNN readers, 1974 was not a year marked by bad music. The Ramones played their first gig. ABBA won Eurovision with the earworm "Waterloo," which became an international hit and launched the Swedes to stardom. Those 365 days were marked by chart-topping debuts, British bangers and prog-rock dystopian masterpieces. Disenchantment, southern pride, pencil thin mustaches and tongue-in-cheek warnings to "not eat yellow snow" filled the soundwaves.

1974 was defined by uncertainty and chaos following a prolonged period of crisis. The ongoing OPEC oil embargo and the resulting energy shortage caused skyrocketing inflation, exacerbating the national turmoil that preceded President Nixon’s resignation following the Watergate scandal. Other major events also shaped the zeitgeist: Stephen King published his first novel, Carrie, Muhammad Ali and George Foreman slugged it out for the heavyweight title at "The Rumble in the Jungle," and People Magazine published its first issue.

Musicians reflected a general malaise. Themes of imprisonment, disillusionment and depression — delivered with sardonic wit and sarcasm — found their way on many of the records released that year. The mood reflects a few of the many reasons these artistic works still resonate.

From reggae to rock, cosmic country to folk fused with jazz, to the introduction of a new Afro-Trinidadian music style, take a trip back 18,262 days to recall 20 albums celebrating their 50th anniversaries in 2024.

Joni Mitchell - Court & Spark

Joni Mitchell’s Court & Spark is often hailed as the pinnacle of her artistic career and highlights the singer/songwriter’s growing interest in jazz, backed by a who’s who of West Coast session musicians including members of the Crusaders and L.A. Express.

As her most commercially successful record, the nine-time GRAMMY winner presents a mix of playful and somber songs. In an introspective tone, Mitchell searches for freedom from the shackles of big-city life and grapples with the complexities of love lost and found. The record went platinum — it hit No.1 on the Billboard charts in her native Canada and No. 2 in the U.S., received three GRAMMY nominations and featured a pair of hits: "Help Me" (her only career Top 10) and "Free Man in Paris," an autobiographical song about music mogul David Geffen.

Gordon Lightfoot - Sundown

In 2023 we lost legendary songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. He left behind a treasure trove of country-folk classics, several featured on his album Sundown. These songs resonated deeply with teenagers who came of age in the early to mid-1970s — many sang along in their bedrooms and learned to strum these storied songs on acoustic guitars.

Recorded in Toronto, at Eastern Sound Studios, the album includes the only No.1 Billboard topper of the singer/songwriter’s career. The title cut, "Sundown," speaks of "a hard-loving woman, got me feeling mean" and hit No. 1 on both the pop and the adult contemporary charts.

In Canada, the album hit No.1 on the RPM Top 100 in and stayed there for five consecutive weeks. A second single, "Carefree Highway," peaked at the tenth spot on the Billboard Hot 100, but hit No.1 on the Easy Listening charts.

Eric Clapton - 461 Ocean Boulevard

Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard sold more than two million copies worldwide. His second solo studio record followed a three-year absence while Clapton battled heroin addiction. The record’s title is the address where "Slowhand" stayed in the Sunshine State while recording this record at Miami’s Criteria Studios.

A mix of blues, funk and soulful rock, only two of the 10 songs were penned by the Englishman. Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s "I Shot the Sheriff," was a massive hit for the 17-time GRAMMY winner and the only No.1 of his career, eclipsing the Top 10 in nine countries. In 2003, the guitar virtuoso’s version of the reggae song was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

Lynyrd Skynyrd - Second Helping

No sophomore slump here. This "second helping" from these good ole boys is a serious serving of classic southern rock ‘n’ roll with cupfuls of soul. Following the commercial success of their debut the previous year, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s second studio album featured the band’s biggest hit: "Sweet Home Alabama."

The anthem is a celebration of Southern pride; it was written in response to two Neil Young songs ("Alabama" and "Southern Man") that critiqued the land below the Mason-Dixon line. The song was the band’s only Top 10, peaking at No. 8 on the Billboard Top 100. Recorded primarily at the Record Plant in Los Angeles, other songs worth a second listen here include: the swampy cover of J.J. Cale's "Call Me The Breeze," the boogie-woogie foot-stomper "Don’t Ask Me No Questions" and the country-rocker "The Ballad of Curtis Loew."

Bad Company - Bad Company

A little bit of blues, a token ballad, and plenty of hard-edged rock, Bad Company released a dazzling self-titled debut album. The English band formed from the crumbs left behind by a few other British groups: ex-Free band members including singer Paul Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke, former King Crimson member bassist Boz Burrel, and guitarist Mick Ralphs from Mott the Hoople.

Certified five-times platinum, Bad Company hit No.1 on the Billboard 200 and No. 3 in the UK, where it spent 25 weeks. Recorded at Ronnie Lane’s Mobile Studio, the album was the first record released on Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label. Five of the eight tracks were in regular FM rotation throughout 1974; "Bad Company," "Can’t Get Enough" and "Ready for Love" remain staples of classic rock radio a half century later.

Supertramp - Crime of the Century

"Dreamer, you know you are a dreamer …" sings Supertramp’s lead singer Roger Hodgson on the first single from their third studio album. The infectious B-side track "Bloody Well Right," became even more popular than fan favorite, "Dreamer."

The British rockers' dreams of stardom beyond England materialized with Crime of the Century. The album fused prog-rock with pop and hit all the right notes leading to the band’s breakthrough in several countries — a Top 5 spot in the U.S. and a No.1 spot in Canada where it stayed for more than two years and sold more than two million copies. A live version of "Dreamer," released six years later, was a Top 20 hit in the U.S.

Big Star - Radio City

As one of the year’s first releases, the reception for this sophomore effort from American band Big Star was praised by critics despite initial lukewarm sales (which were due largely to distribution problems). Today, the riveting record by these Memphis musicians is considered a touchstone of power pop; its melodic stylings influenced many indie rock bands in the 1980s and 1990s, including R.E.M. and the Replacements. One of Big Star’s biggest songs, "September Gurls," appears here and was later covered by The Bangles.

In a review, American rock critic Robert Christgau, called the record "brilliant and addictive." He wrote: "The harmonies sound like the lead sheets are upside down and backwards, the guitar solos sound like screwball readymade pastiches, and the lyrics sound like love is strange, though maybe that's just the context."

The Eagles - On the Border

The third studio record from California harmonizers, the Eagles, shows the band at a crossroads — evolving ever so slightly from acoustically-inclined country-folk to a more distinct rock ‘n’ roll sound. On the Border marks the studio debut for band member Don Felder. His contributions and influence are seen through his blistering guitar solos, especially in the chart-toppers "Already Gone" and "James Dean."

On the Border sold two million copies, driven by the chart topping ballad "Best of My Love" — the Eagles first No.1 hit song. The irony: the song was one of only two singles Glyn Johns produced at Olympic Studios in London. Searching for that harder-edged sound, the band hired Bill Szymczyk to produce the rest of the record at the Record Plant in L.A.

Jimmy Buffett - Livin’ and Dyin in ¾ Time & A1A

Back in 1974, 28-year-old Jimmy Buffett was just hitting his stride. Embracing the good life, Buffett released not just one, but two records that year. Don Grant produced both albums that were the final pair in what is dubbed Buffett’s "Key West phase" for the Florida island city where the artist hung his hat during these years.

The first album, Livin’ and Dyin’ in ¾ Time, was released in February and recorded at Woodland Sound Studio in Nashville, Tennessee. It featured the ballad "Come Monday," which hit No. 30 on the Hot 100 and "Pencil Thin Mustache," a concert staple and Parrothead favorite. A1A arrived in December and hit No. 25 on the Billboard 200 charts. The most beloved songs here are "A Pirate Looks at Forty" and "Trying to Reason with Hurricane Season."

Buffett embarked on a tour and landed some plume gigs, including opening slots for two other artists on this list: Frank Zappa and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Genesis - The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

Following a successful tour of Europe and North America for their 1973 album, Selling England by the Pound, Genesis booked a three-month stay at the historic Headley Grange in Hampshire, a former workhouse. In this bucolic setting, the band led by frontman Peter Gabriel, embarked on a spiritual journey of self discovery that evolved organically through improvisational jams and lyric-writing sessions.

This period culminated in a rock opera and English prog-rockers’s magnum opus, a double concept album that follows the surreal story of a Puerto Rican con man named Rael. Songs are rich with American imagery, purposely placed to appeal to this growing and influential fan base across the pond.

This album marked the final Genesis record with Gabriel at the helm. The divisiveness between the lyricist, Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks came to a head during tense recording sessions and led to Gabriel’s departure from the band to pursue a solo career, following a 102-date tour to promote the record. The album reached tenth spot on the UK album charts and hit 41 in the U.S.

David Bowie - Diamond Dogs

Is Ziggy Stardust truly gone? With David Bowie, the direction of his creative muse was always a mystery, as illustrated by his diverse musical legacy. What is clear is that Bowie’s biographers agree that this self-produced album is one of his finest works.

At the point of producing Diamond Dogs, the musical chameleon and art-rock outsider had disbanded the band Spiders from Mars and was at a crossroads. His plans for a musical based on the Ziggy character and TV adaptation of George Orwell’s "1984" both fell through. In a place of uncertainty and disenchantment, Bowie creates a new persona: Halloween Jack. The record is lyrically bleak and evokes hopelessness. It marks the final chapter in his glam-rock period — "Rebel Rebel" is the swaggering single that hints at the coming punk-rock movement.

Bob Marley - Natty Dread

Bob Marley’s album "Natty Dread," released first in Jamaica in October 1974 later globally in 1975, marked his first record without his Rastafari brethren in song Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer. It also introduced the back-up vocal stylings of the I Threes (Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths.)

The poet and the prophet Marley waxes on spiritual themes with songs like "So Jah Seh/Natty Dread'' and political commentary with tracks,"Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)" and "Rebel Music (3 O’clock Road Block)." The album also Includes one of the reggae legend’s best-loved songs, the ballad "No Woman No Cry," which paints a picture of "government yards in Trenchtown" where Marley’s feet are his "only carriage."

Queen - Sheer Heart Attack

The third studio album released by the British rockers, Queen, is a killer. The first single, "Killer Queen," reached No. 2 on the British charts — and was the band’s first U.S. charting single. The record also peaked at No.12 in the U.S. Billboard albums charts.

This record shows the four-time GRAMMY nominees evolving and shifting from progressive to glam rock. The album features one of the most legendary guitar solos and riffs in modern rock by Brian May on "Brighton Rock." Clocking in at three minutes, the noodling showcases the musician’s talent via his use of multi-tracking and delays to great effect.

Randy Newman - Good Old Boys

Most recognize seven-time GRAMMY winner Randy Newman for his work on Hollywood blockbuster scores. But, in the decade before composing and scoring movie soundtracks, the songwriter wrote and recorded several albums. Good Old Boys was Newman’s fourth studio effort and his first commercial breakthrough, peaking at No. 36 on the Billboard charts.

The concept record, rich in sarcasm and wit, requires a focused listen to grasp the nuances of Newman’s savvy political and social commentary. The album relies on a fictitious narrator, Johnny Cutler, to aid the songwriter in exploring themes like "Rednecks" and ingrained generational racism in the South. "Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man)" is as relevant today as when Newman penned it as a direct letter to Richard Nixon. Malcolm Gladwell described this record as "unsettling" and a "perplexing work of music."

Frank Zappa - Apostrophe

Rolling Stone once hailed Frank Zappa’s Apostrophe as "truly a mother of an album." The album cover itself, featuring Zappa’s portrait, seems to challenge listeners to delve into his eccentric musical universe. Apostrophe was the sixth solo album and the 19th record of the musician’s prolific career. The album showcases Zappa’s tight and talented band, his trademark absurdist humor and what Hunter S. Thompson described as "bad craziness."

Apostrophe was the biggest commercial success of Zappa’s career. The record peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard Top 200. The A-side leads off with a four-part suite of songs that begins with "Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow" and ends with "Father Oblivion," a tale of an Eskimo named Nanook. The track "Uncle Remus," tackles systemic racism in the U.S. with dripping irony. In less than three minutes, Zappa captures what many politicians can’t even begin to explain. Musically, Apostrophe is rich in riffs from the two-time GRAMMY winner that showcases his exceptional guitar skills in the title track that features nearly six minutes of noodling.

Gram Parsons - Grievous Angel

Grievous Angel can be summed up in one word: haunting. Recorded in 1973 during substance-fueled summer sessions in Hollywood, the album was released posthumously after Gram Parsons died of a drug overdose at 26. Grievous Angel featured only two new songs that Parsons’ penned hastily in the studio "In My Hour of Darkness" and "Return of the Grievous Angel."

This final work by the cosmic cowboy comprises nine songs that have since come to define Parson’s short-lived legacy to the Americana canon. The angelic voice of Emmylou Harris looms large — the 13-time GRAMMY winner sings harmony and backup vocals throughout. Other guests include: guitarists James Burton and Bernie Leadon, along with Linda Ronstadt’s vocals on "In My Hour of Darkness."

Neil Young - On The Beach

On the Beach, along with Tonight’s the Night (recorded in 1973, but not released until 1975) rank as Neil Young’s darkest records. Gone are the sunny sounds of Harvest, replaced with the singer/songwriter’s bleak and mellow meditations on being alone and alienated.

"Ambulance Blues" is the centerpiece. The nine-minute track takes listeners on a journey back to Young’s "old folkie days" when the "Riverboat was rockin’ in the rain '' referencing lament and pining for time and things lost. The heaviness and gloom are palpable throughout the album, with the beach serving as an extended metaphor for Young’s malaise.

Dolly Parton - Jolene

Imagine writing not just one, but two iconic classics in the same day. That’s exactly what Dolly Parton did with two tracks featured on this album. The first is the titular song, "Jolene," recorded at RCA Studio B in Nashville. The song has been covered by more than a dozen artists.

Released as the first single the previous fall, "Jolene," rocketed to No.1 on the U.S. country charts and garnered the 10-time GRAMMY winner her first Top 10 in the U.K. The song was nominated for a GRAMMY in 1975 and again in 1976 for Best Country Vocal Performance. However, it didn’t take home the golden gramophone until 2017, when a cover by the Pentatonix featuring Parton won a GRAMMY for Best Country Duo/Group Performance.

Also included on this album is "I Will Always Love You," a song that Whitney Houston famously covered in 1992 for the soundtrack of the romantic thriller, The Bodyguard, earning Parton significant royalties.

Barry White - Can’t Get Enough

The distinctive bass-baritone of two-time GRAMMY winner Barry White, is unmistakable. The singer/songwriter's sensual, deep vocal delivery is as loved today as it was then. On this record, White is backed by the 40-member strong Love Unlimited Orchestra, one of the best-selling artists of all-time.

White wrote "Can’t Get Enough of Your Love, Babe," about his wife during a sleepless night. This song is still played everywhere — from bedrooms to bar rooms, even 50 years on. In the U.S., the record hit the top of the R&B pop charts and No.1 on the Billboard 200. Although the album features only seven songs, two of them, including "You’re the First, the Last, My Everything" reached the top spot on the R&B charts.

Lord Shorty - Endless Vibrations

Lord Shorty, born Garfield Blackman, is considered the godfather and inventor of soca music. This Trindadian musician revolutionized his nation’s Calypso rhythms, creating a vibrant up-tempo style that became synonymous with their world-renowned Carnival.

Fusing Indian percussion instrumentation with well-established African calypso rhythms, Lord Shorty created what he originally dubbed "sokah," meaning, "calypso soul." The term soca, as it’s known today, emerged because of a journalist’s altered writing of the word, which stuck. The success of this crossover hit made waves across North America and made the island vibrations more accessible outside the island nation.

Artists Who Are Going On Tour In 2024: The Rolling Stones, Drake, Olivia Rodrigo & More

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: John Swannell

interview

Living Legends: Duran Duran Are Still Hungry After All These Years

In a career-spanning interview, Duran Duran bassist John Taylor and drummer Roger Taylor discuss surviving cultural shifts and the breadth of the band's discography.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music still going strong today. This week, GRAMMY.com spoke with members of Duran Duran. The band is currently on tour with Nile Rodgers.

One of the biggest bands of the 1980s, Duran Duran captured the decade's exuberant pop ethos and influenced much of its fashion sense. Four decades later, the group remains ever-popular thanks to beloved hits, a potent live show, and their particular combination of the nostalgic and contemporary.

Originally considered a teen band for their good looks, stylish dress, and sexy videos, the British pop-rock quintet have proved to be far more than an '80s time capsule, though their output from the period endures.

Duran Duran’s first three studio albums and live release Arena were big hits in the early ‘80s. Their smash "Hungry Like The Wolf" won two GRAMMY Awards in 1984: Best Video Album and Best Video, Short Form. In 1985, they temporarily split into two popular side projects, Arcadia and Power Station, while simultaneously releasing their second No.1 hit as Duran Duran (the theme song to the James Bond movie A View To A Kill).

Lineup upheaval followed. Overwhelmed by their massive success, drummer Roger Taylor departed the band and the music industry in 1986. Guitarist Andy Taylor went on to a rock-based solo career as an artist and producer. Frontman Simon LeBon, keyboardist Nick Rhodes, and bassist John Taylor continued on and brought guitarist Warren Cuccurullo into the fold in 1988.

Buoyed by the melancholy hits "Ordinary World" and "Come Undone," Duran Duran’s self-titled 1993 release (a.k.a. The Wedding Album) achieved platinum status. John Taylor departed for two albums in ‘97, but the classic line-up reunited and made the successful comeback album Astronaut in 2004. Andy departed again ahead of 2007's poppy Red Carpet Massacre (featuring appearances by Justin Timberlake and Timbaland), and current guitarist Dom Brown joined their ranks.

Since that time, Duran Duran have released three more albums (including the Top 10 seller Paper Gods), collaborated with Kiesza, Janelle Monáe, and John Frusciante, and were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame.

Duran Duran are currently touring with Nile Rodgers and Chic — a fortuitous bill as members of Chic and Duran Duran became close friends and collaborators in the ‘80s. Duran’s latest album, 2021's Future Past, combines elements of their classic sound with contemporary influence from Blur’s Graham Coxon, producer/composer Giorgio Moroder, and notable guest appearances by GRAMMY-nominated Swedish singer Tove Lo and the genre-bending Japanese band Chai.

Bassist John Taylor and drummer Roger Taylor spoke to GRAMMY.com about the band's history and what makes them tick. After these interviews were conducted, guitarist Andy Taylor announced his first solo album in 33 years, Man’s A Wolf To Man. Taylor has been battling stage four prostate cancer for several years, and Duran Duran’s first show of the current U.S. tour on Aug. 19 will raise funds for him.

You've been playing the eerie "Night Boat" from your debut, on this tour. That song goes back to your Rum Runner club days in Birmingham.

Roger Taylor: It's a pretty deep and epic piece of music, isn't it, for a bunch of 20-year olds? I was very impressed when we started to play it again because the arrangement is pretty out there. It's not your normal three or four minute pop song.

All You Need Is Now from 2010 is probably the most ‘80s of your 2000s albums. However, a song like "The Man Who Stole A Leopard" is not something you would have heard from Duran Duran back in the day.

Roger Taylor: [Producer] Mark Ronson had that idea that we shouldn't be ashamed of ourselves. He said, "There's so many bands out there that are copying you or citing you as an influence that you shouldn't be ashamed to be who you are."

And I think Mark Ronson definitely set us on the path to some sort of modern day self-discovery where we actually stopped running away from who we are. I think we did spend a lot of time completely trying to reinvent ourselves and sound completely different. I think Red Carpet Massacre [in 2007] was the tip of that iceberg. I think we've gone back into a little bit more of an organic sound. We've focused a little bit more on John and I playing together again. Nick [brought] out some of his organic synths from the early days. We've accepted ourselves and that got us to where we are now.

John, I once read that you felt you overplayed on the early albums. How do you look back now on your playing?

John Taylor: You're learning tricks as you go along. When the first record came out in ‘81, I'd probably been playing bass for two years. What I'm playing on that first album is everything I know how to play. There's no selection process. It's Roger and I just trying to come up with grooves and licks and transitions — how should we go from this bit to this — and it was great, great fun.

There was a hierarchy of musicianship [in the band], if you will, but it wasn't that great that anybody felt left out. I think that's the key to any group of musicians really. If you've only been playing a year or two you don't want to be around virtuosos because you're always going to be catching up.

Roger, you’re intensely submerged beneath your headphones onstage. You have this juggling act of keeping the groove going, but occasionally things have to be locked in if there's some sequencing or rhythm programming going on. I assume that’s very challenging?

Roger Taylor: It's always been quite a challenging gig because, as you very rightly say, we're trying to keep an organic quality within the live performance. But then Nick is playing parts that are very rhythmic. We use a lot of sequencers, rhythm boxes, and programmed pieces of rhythm, and I have to keep in time with that.

So that's quite a tough job for two hours to make sure that you don't go out of time, you don't vary the tempo. It has to be really locked in. I now use a hybrid kit which is a mix of the live sound and samples from the record which are triggered by the live drums. So when you hear in the kit up front, you're hearing some of the live kit, but you're also hearing some electronic sounds mixed in with the kit.

John, you've played alongside three very distinctive guitarists – Andy Taylor, Warren Cuccurullo, and now Dom Brown. What's it been like for you to play alongside each of them?

John Taylor: Andy was very creative, and he just landed on top of this thing that Nick, Roger, and I had developed. We'd been working on this theoretical rhythm section – well, it wasn't theoretical, we were actually doing it – and we were firing off sequencers and copying our Chic riffs and developing this vibe. Andy just came in and found his way into what we were doing and took it to another level.

Warren's artistically a very powerful, very deep musician. The period of time that we were with Warren was interesting. The first couple of records we did with Warren we would really direct what we wanted him to do, but I remember going through a period in the ‘90s where I just stepped back. I didn't have all that much energy for the band at the time, and Warren just rose into this. Probably the greatest thing we did with Warren was "MTV Unplugged." He was really given the task to arrange that, and he did some very, very clever things.

Dom is old school, meaning he takes the guitar very seriously. He's a lead guitarist. I could count the amount of bum notes he's played with us over the years on one hand. He loves to jam. I think that the journey with him really has been convincing him of the [equal] importance of rhythm playing and just getting him to think like Steve Cropper and think like Nile [Rodgers].

In the mid-1980s Simon, Nick, and Roger were in Arcadia, and John and Andy went to Power Station. They represented two driving aesthetics with the band over the years: the atmospheric and at times darker side with the former, and the groove-oriented material with the latter. Duran’s "Night Boat" is such an interesting tune because it works in both ways. I don’t think some people realize how multifaceted this band is.

Roger Taylor: I think that was overlooked in the early ‘80s. We had a young female audience that used to come to the gigs and scream for most of the shows. We used to walk out and start with “Is There Something I Should Know?” and as the curtain would rise it would just be a deafening, high-pitched squeal. We really struggled to hear what we were playing, to be honest with you.

I think people assumed that we were just a teen band that was just releasing these quite poppy singles. There was always what I call the dark side of Duran, and I think it took a few years for people to really appreciate that, that we had another side musically.

Andy loved AC/DC, Nick wanted us to sound like Kraftwerk, John and I wanted to sound like Chic. So we just had this mash of different influences that somehow created something very original. When I listen to "Hungry Like The Wolf," that couldn't be anybody else. Although we were trying to be other people at the time, I think we created something that's very original.

**I hear the darker side in a song like "The Chauffeur" from Rio or "Invisible" from Future Past. I also like the dreaminess of Arcadia’s "The Promise" a lot.**

Roger Taylor: I’ve gotta say, that [latter song] is one of my favorite piece of musics that I've ever played on. I really love that song, and [Pink Floyd’s] Dave Gilmour plays guitar on it. It had Sting on backing vocals. It was an epic song, and I think it’s really stood the test of time.

**John, you have mentioned how you felt Simon really matured as a lyricist on The Wedding Album, especially with "Ordinary World” moving into a more personal area.**

John Taylor: To some extent, there was a throwing out the baby with the bathwater at the end of the ‘80s, and Duran were struggling to stay in the game. We took a lot of criticism for the very things that actually made us special. I look back on Simon's lyrics now from the early ‘80s — lyrics like “Cracks In The Pavement” or "New Moon On Monday" — and "The Reflex" is as enigmatic a pop song as [Bob Dylan's] "A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall" and very weirdly interesting. Try getting that into the Top 30 today, you just couldn't do it.

It just felt like there'd been such a shift musically and lyrically by the end of the ‘80s. We were quite keen to try to bring a greater sense of realism. I was tired of people saying, "What are those lyrics about anyway?" So Simon started experimenting a little bit with feelings, lyrics responding to emotional circumstances. And he reached it with "Ordinary World" and "Come Undone," two of the greatest lyrics of the ‘90s on the same album.

When you're making music for as long as we've been making music…you're always questioning where you should be and what you should be doing in relation to your audience. From the ‘90s onward we had two bags that we could dip into: We had the detached, enigmatic, weird s—, and then we had the emotionally direct [songs]. I think for Simon it really helps when he has a theme.

We have this sandbox, and when we write together we get all excited. We all just set up in a room and start jamming. Simon's jamming on the voice or he might pull in a guitar, and he's got to pick his way through. I'm usually the first one [done]. “I’ve got the bass line!” Then a month later Nick's got the keyboard parts, and Simon's still trying to make sense of what his vocal sketches mean or what they could mean. And it's really difficult. I always say it's never been easy to make reasonably interesting music.

2006's Reportage was shelved, but there's a possibility it might be released. From what I understand, the album is a bit more political, which is not typical of Duran Duran. Nick once described it as more of an edgy record. Do you remember recording it?

John Taylor: David Byrne was saying on CNN yesterday — everything's political these days, it doesn't matter what you do. Reportage was realism. That's why we call it Reportage – it felt very much like music that was reflecting stories in the news.

There was a song on there that Simon had written about the Labour government in the UK, and I remember Nick and he got into a mighty argument about that. Duran Duran lyrics [should have] a fine gauze over the words, in a way. There's got to be a little bit of smoke, a little bit of atmosphere around the words. I think Simon is definitely interested in meeting the challenge of lyric writing, whether that is the perfect love song, a highly obtuse piece of intellectual wordplay, or some song that moves forward a cause of some kind.

John, a few years ago Nick told me that you and he were working on a musical, and it wasn't going to be a traditional musical. How is that coming along?

John Taylor: It's on hold at the moment. It was a really interesting exercise. I feel that we learned a lot in the writing of it – right back to that learning about a theme, learning about writing for characters, writing to move the plot forward.

It's very likely that it'll see the light of day one day. Not everything has to see the light of day. Sometimes something can be like R&D and be just as important. But getting something like that onto the stage is a big undertaking.

Duran Duran originally peaked during an incredibly decadent time in the music industry when there was a lot of money being spent. Roger, you retired from music for a decade to live a normal life. When you talk to younger musicians who want to know about it, how would you describe that period of the ‘80s?

Roger Taylor: It was certainly a crazy period, and it was incredibly decadent. The record companies seemed to have endless millions that they'd made through the ‘70s [and] they were making millions again because they were releasing CDs. I remember going into EMI in Manchester Square in London — the record executives would have grand pianos in their offices and they'd be driving Rolls Royces and Jaguars and they'd be signing a dozen bands a month.

We were just lucky that we made the next step. Very unusually, we managed to break America which was huge — and not just the edges of America. We broke all across America. It was just a wonderful period of different steps and opportunities that we just took, and everything just went right for us.