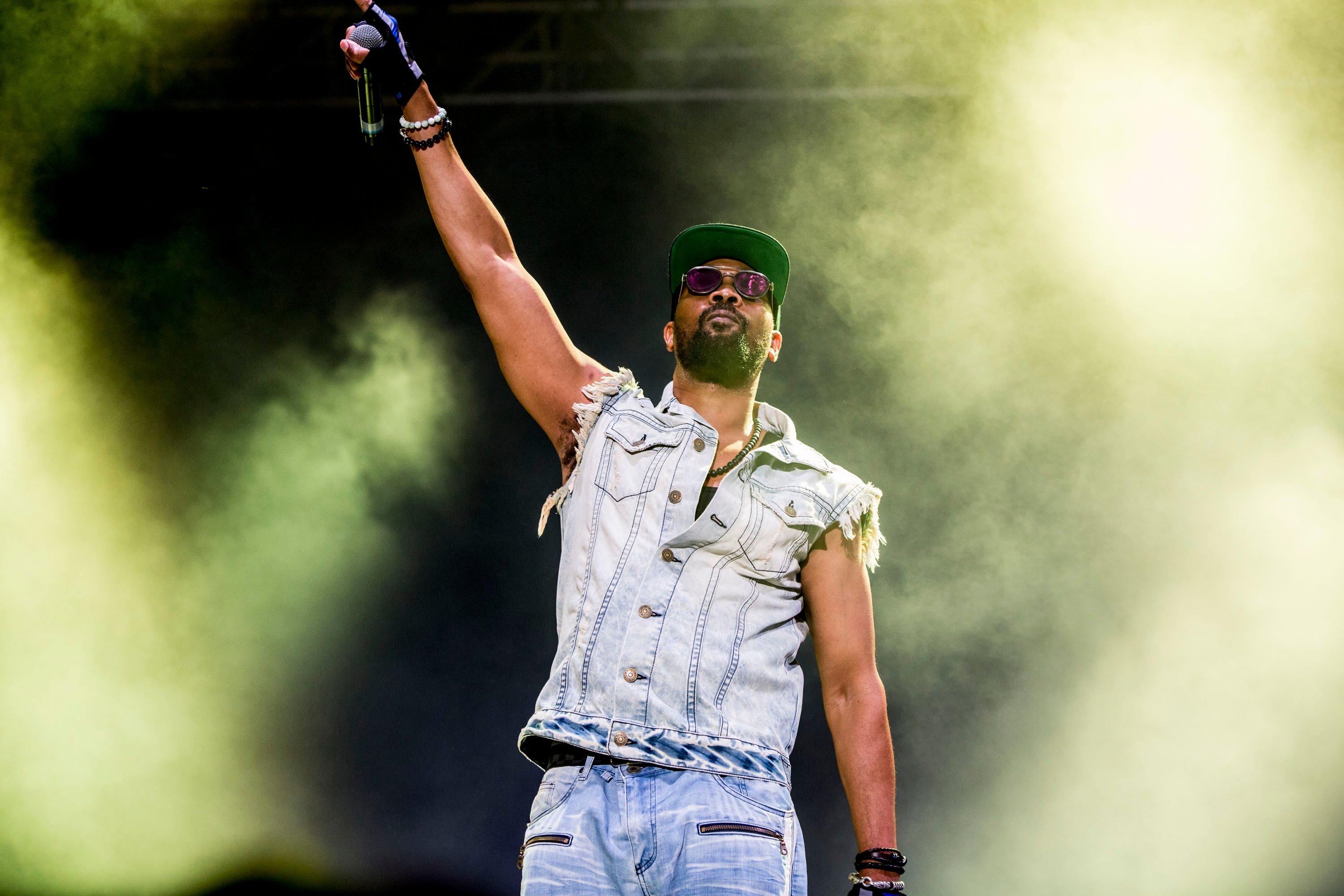

Credit: Harmony Gerber/Getty Contributor

interview

RZA’s Constant Elevation: From Wu-Tang to 'Kill Bill,' The Rapper/Producer Discusses His Creative Process And History Ahead Of Bobby Digital Reprise

“RZA has a certain responsibility ... Bobby Digital offered escapism,” rapper/producer RZA tells GRAMMY.com. Ahead of his new album as Bobby Digital, 'Saturday Afternoon Kung Fu Theater,' the multi-hyphenate discusses his artistic evolution.

Artists who’ve stretched their careers past the unimaginable often come full circle; at no point do they ever really lose the foundations that moved them to begin with. Robert Diggs — known as the RZA — is having one of those full-circle moments. After founding a record label and clothing brand, creating comic books and soundtracking Hollywood hits, today he admits: “Now, I can get back to my foundational love that started it all, which is and will always be, hip-hop.”

Diggs’ — a.k.a. Zig-Zag-Zig Allah, a.k.a. Prince Rakeem, a.k.a. the RZArector (among his many monikers through the decades) — career began through homespun demos with cousins and neighborhood friends in Staten Island. RZA’s supreme mathematics with the Wu-Tang Clan were well known by 1994, when Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) forever changed rap with uncanny ballistics not seen before or since. As Wu-Tang’s visionary, RZA famously masterminded their record deals and single-handedly produced all the vaunted material; his group mentality aiding everyone’s collective ascension.

RZA then transcended Shaolin, landing in Hollywood to oohs and ahs in the late ‘90s, where he scored Jim Jarmusch’s meditative film Ghost Dog: Way Of The Samurai. Yet it wasn’t until 2012’s The Man With The Iron Fists — a film produced by Quentin Tarantino starring Russell Crowe which RZA co-wrote and directed — that he felt he’d finally arrived. “My evolution to manhood began with that film,” he tells GRAMMY.com.

“At that point I became a master. It took me many years but I really felt like I evolved into the artist I am today after that project.” His voice now a bit dustier, but RZA’s energy and enunciation rings familiar. “I felt like I could run a small country after that.”

In 1998 he once again emerged solo, this time as Bobby Digital — a character and concept album woven with fantastical tales over fewer sampled beats, creating an atmosphere that was equal parts Blaxploitation and futuristic street narrative. Hearsay tells us that a Bobby Digital film was even in the works, though it never materialized and remained the final word regarding the Digital persona — until recently.

After 20 years, RZA has boomeranged to Bobby Digital with Saturday Afternoon Kung Fu Theater, out March 4. Bobby Digital’s return pays homage to the Shaw Brothers — Hong Kong’s largest film company, operating for an astounding 86 years, with almost every notable kung fu ever made film under their banner — while evolving the album’s namesake character. GRAMMY-nominated producer DJ Scratch nails the sample palette, creating an epic undertone of kung fu dialogue and sound effects.

Reprising the Digital the character gave RZA a sense of liberation. “It was freeing just rapping and spitting verses all over,” he says. “It was fun trying to match my words to the vibe of the beats and just using all kinds of different cadences again.”

From his pre-Wu days, to the making of “C.R.E.A.M.”, to his production epoch, and his celebrated film work, GRAMMY.com demystifies and unpacks the many histories that orbit one Robert Diggs.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I want to start at the beginning and move forward: While “Protect Ya Neck” was the first single, “C.R.E.A.M.” likely introduced Wu-Tang to many and still resonates. What comes to mind when you think of it today?

“C.R.E.A.M.” was a song that actually took three four different evolutions before it became final. At one time it was called “I’m On Some S**t.” And later on, there was a version with just me and Ghostface. Then, later there was a version with just Raekwon and [Inspectah] Deck. That one was called “Lifestyles Of The Mega Rich” and it was 12 minutes long. [Laughs]

When we got the deal to make [36 Chambers], I wanted to use it because I knew that the beat was special. I knew that the vibe between Raekwon’s voice and Deck’s voice was the best. But as we was doing it, it just seemed like something else had to happen.

For instance?

We needed a hook. And so at the time, the best person to do hooks was Method Man. He was a melodic member of the crew and was always very witty with his hooks. I was like, “Yo, I need a hook for this” and he was casual about everything and came back with “C.R.E.A.M. get the money. Dolla dolla bill.”

We touched on “C.R.E.A.M.” but does RZA have a favorite Wu-Tang song?

I don't know, my favorite changes. But recently I've just been really impressed with the way I did “Bring Da Ruckus.” I used a CD skipping as my horn. Even to me, that sounds like I really was innovative back then.

I was trying to complete a story…and it made sense to me that I needed a horn. While I was looking for samples, the CD started skipping so I sampled that sound. Then I slowed it down and it became the tata tata tata tata tata that you hear. So the orchestration of this song and how it came together finally means a lot to me. I’m just really impressed to think of my young mind being able to compose that without even knowing what a C chord was.

As the producer of Wu-Tang Clan, what an embarrassment of riches to have those MCs to produce for.

Each member had something unique and I knew them all. They all knew each other but I was the denominator; I did demos with all of them. There’s a demo with just me and Ghostface. There’s a demo of Dirty and GZA and so on. Some of these tapes go back to when I was 12.

When [my debut solo project] Prince Rakeem happened, I had a little record deal and felt like I understood the industry a little bit. Even then I was like, “The best talent my ears have heard are homies that I've been doing demos with my whole f***ing life!” So I went and told execs that we got something different and that we had that Wu-Tang slang. Bong bong.

Do you mind sharing your decision to leave high school? What was your family’s reaction?

To keep myself motivated, I just wanted to record and record. That's why I dropped out of school.

I don't think I ever made this public, but it was my mom that actually signed me out of school. At first I was just absent so much that they’d send people to our house. And my mother said she was gonna do whatever I wanted; I told her I just wanted to do music. So she drove me up to the school and the lady asked us, “You sure you want to do this?” I was 16 years old at the time and my mom signed me out, and I went for it.

Thanks for that. What strikes you now looking back on that transitional stage in life?

I came in as this young man that had his heart and energy focused on writing songs and making music. The problem that I had, though, was nobody believed in me as a producer.

Acclaimed producer Easy Mo Bee produced your first released material during your Prince Rakeem era. Tell us about your early development and how that impacted you as a young producer.

I may have had like a hundred beats at that point. And a hundred ain't enough to be at the master level. I was making these beats with the Roland and a 4-track Yamaha. I didn’t even have a sampler; I would just scratch in samples live. I met Easy Mo Bee with his brother and they had an SP 1200 and were killing it. I was just enamored by that. I saw that machine and didn’t know what it did and Mo Bee would just make a beat right in front of me. Mo was dope. I would to go to his house a lot. I wanted him to produce my whole album, and he gave me a couple tracks. I couldn't afford him at the time. [Laughs]

We’d be remiss to not mention your Gravediggaz project with Prince Paul, 1994’s 6 Feet Deep. Looking back, do you think you guys invented “horrorcore?” And please touch on Paul’s importance for us.

We never wanted to call it “horrorcore.” That was a title that the writers started calling it. But I do think we definitely pioneered it. Nobody else was doing it in front of us. You could give credit to The Geto Boys too, like “Mind Playing Tricks On Me” or “Mind Of A Lunatic.” They were pretty dark, but it wasn't spiritually dark like us.

Prince Paul is a producer who brought skits to the whole album format for hip-hop. His creativity was there before all of us. Paul was definitely a pioneer on interludes and being able to add abstractness. He made Gravediggaz happen. His choices were just different.

You have a new Bobby Digital project out soon, but I want to talk about the first one, Bobby Digital In Stereo. What did this allow you to do that was different from the RZA?

RZA has a certain responsibility, so I had to protect that persona. Bobby Digital offered escapism for me. I was in the studio smoking and drinking and I just had this insight that the whole world's gonna be digital. I felt like I became a digital being around that time. Whatever combination of drugs I had that night, I did more. And did it again. I remember I couldn’t feel my hands! And then I thought of my birth name, which is Robert Diggs, Bobby Digs. So I knew I had to be Bobby Digital.

Production wise, it had less samples, more strings and keys. What are your thoughts when you look back on that era of your production?

I didn’t want to do RZA anymore. Thinking back, I think it helped open up the fact that hip-hop could be electronic music and not only sample based. Maybe more kids got Triton keyboards after that instead of samplers. I still wasn't musically trained like I am now. What I love about the album in particular and its vibe, is that I was bold and tried weird s***. With the new Bobby Digital, I wanted to bring it back and be positive about everything.

On My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Watch The Throne, you worked with Kanye, who like yourself both raps and produces. What was that experience like and did you have any takeaways?

Working with him was great because Ye has the ability to bring a lot of energy and people together to create. He was the first artist that I met personally that treated his project like how a boxer prepares for a fight. The regimen of him and his crew and all the dedication to that moment of creativity. I had never seen that before.

When Wu did it, we were all sort of at the studio and we were all dedicated, but it wasn't scheduled. For us, the studio was like a clubhouse, it’s where you’re going. But with Kanye, the scenario was that the team would get up and eat breakfast together. Then do something recreational together and another activity. But at 4 o'clock we’re all going to be at the studio.

I want to move to your film work. There’s Afro Samurai and of course the scores for both Kill Bills. Touch on Tarantino and describe your mind state when scoring a film versus production.

Artists sometimes come together and I think it’s destiny. Our relationships come out of a love for art. With Tarantino, we’re just both big kung fu heads and our friendship started by watching movies. He’d call and say, “I'm in town, come over. I got this film.”

With scoring a movie, you lose your freedom. You’re there to complement the story and as well as have a story to tell through music. It’s more trial and error. Once your brain gets the process, it all makes sense. I had a scene where the music started right when the girl in the scene opened her eyes. It was very subtle. It was magic. You need to communicate to the audience as the composer.

Let’s touch on directing The Man with Iron Fists. You grew up on kung fu films. Was it hard to take all your influences and not make a 5-hour kung fu epic?

The first cut of the film was over three hours! But to be real with you, Dave, and to be real with your readers, I’ll tell you how I put out art. You need three things: inspiration, imagination and aspiration. All of those words, there's an action to it. There's an internal spirit and movement. All these things are important.

I was just so happy that I was able to share this with the world. It was the most difficult artistic expression I had ever done to date. It was the greatest challenge of my life. And when I finished it, I became a full-blown artist and a full-blown man. I truly believe that.

When it comes to films, what inspires you most: scoring, acting or directing? And what do you exactly mean by it helped you “evolve?"

Directing is the greatest because as a director, you have all the control. I wrote, directed, acted and scored it. My signatures were on everything. Moviemaking is the most expensive form of art creation. It is your responsibility to protect everybody's interest and money and time and still tell a story while doing it. And that's why I said I became a full-blown man because after that. To me, it was almost the epitome of artistic creation. But now, I can get back to my foundational love that started it all, which is and will always be hip-hop.

Photo: William Richards, courtesy of VP Records

feature

Morgan Heritage’s 'Don’t Haffi Dread' At 25: How Rasta Sibling Group Created A Roots Rock Anthem & Brought Spirituality To The World

In their first interview since the passing of Peetah Morgan, siblings Una, Gramps and Mojo of GRAMMY-winning reggae band Morgan Heritage reflect on the 25th anniversary of their breakthrough roots reggae album.

In the late '90s, a time when synthesized dancehall riddims dominated Jamaica’s airwaves, Rastafarian sibling band Morgan Heritage remained steadfast in their dedication to roots reggae. Their passion would resonate internationally via 1999's Don’t Haffi Dread, an album that brought renewed vitality and youthful enthusiasm to roots reggae.

Released via New York label VP Records on March 23, 1999, Don’t Haffi Dread was a personal and professional advancement for Morgan Heritage, earning the band widespread accolades and a designation as reggae’s future. Filled with rebel statements, spiritually empowering sentiments and R&B-infused lover’s rock, Don’t Haffi Dread is perhaps remembered most for its title track. The song's catchy and somewhat contentious lyric, "yuh don’t haffi dread to be rasta," asserted that listeners don't have to wear dreadlocks to embrace Rastafari’s teachings.

Decades later, the song remains one of the most popular in the group’s expansive catalog. "That was the first time a Rastafarian said something like that on record," the group’s lead singer Peetah Morgan told me at the time of Don’t Haffi Dread’s release, in an interview for Air Jamaica’s SkyWritings Magazine. "It caused a lot of controversy and got us a lot of attention, even in places we had never performed."

Although it was the band’s fourth album, Don’t Haffi Dread was the first time they recorded playing their instruments live in the studio. This was a remarkable achievement, Peetah explained, "because it was done at a time when we were told live recording would never come back to Jamaica."

Peetah’s vocal dynamism led the band’s many heartfelt appeals for unity as persuasively as his paeans to Jah can stir the souls of the most hardened non-believers. He died at age 50 on Feb. 25.

"The journey has been a blessing. May God continue to keep our brother Peetah," says keyboardist and vocalist Una Morgan. "Our dad used to compare us to a body with two hands, two feet and Peetah was our head; to be celebrating this album in Peetah’s honor is the greatest feeling ever."

In their first interview since Peetah's passing, members of Morgan Heritage reflected on the 25th anniversary of their breakthrough album. "Recording Don’t Haffi Dread…we honed our craft and became a force to be looked at; now we are called icons, legends," Una continues.

Don’t Haffi Dread established Morgan Heritage as one reggae’s most popular acts and one the very few self-contained bands to emerge from Jamaica in the 1990s. "Everything opened up for Morgan Heritage with the release of Don’t Haffi Dread," comments Cristy Barber, former Head of A&R, VP Records. "They were featured on a segment on 'CBS Sunday Morning' with their father; they played a private party for Johnny Cash, performed before an audience of millions on the televised Special Olympics and became the first reggae band on the Vans Warped Tour."

Morgan Heritage are five of the 30 children of the late Jamaican singer Denroy Morgan, whose 1981 hit "I’ll Do Anything For You" reached the Top 10 on Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart. Siblings Memmalatel "Mr. Mojo" (percussion, vocals), Nakhamyah "Lukes" (guitar), Roy "Gramps," (vocals, keyboards), and the band’s sole female member Una, and Peetah were raised in Rastafarian households. They lived in Springfield, Massachusetts, where they attended school, and spent weekends in Brooklyn, immersed in music studies.

In 1992, Morgan Heritage was an eight member aggregation that included older siblings David, Denroy Jr. and Jeffrey. Immediately following their debut performance at Jamaica’s now defunct Reggae Sunsplash festival, they were signed to MCA Records and released one album, 1994's pop-reggae leaning Miracle. Displeased with the label’s lack of support, the Morgans chose not to record a second album for the company. With their increasing personal responsibilities, including caring for their young children, David, Denroy Jr., and Jeffreyleft the group.

However, it was papa Denroy’s decision to return to his Jamaica birthplace in 1995 that put Morgan Heritage on their path to success. Morgan Heritage’s remaining five members, now in their early to mid 20s, followed their dad to Jamaica. The band spent over a year alternating between morning recording sessions with producer Lloyd "King Jammy" James and afternoons with producer Robert "Bobby Digital" Dixon. The band wrote songs and recorded their vocals over pre-made riddims (rhythm tracks), a standard practice in Jamaican music making. Their diligence yielded two albums: the Digital-produced Protect Us Jah and One Calling, produced by Jammy.

The band returned to Bobby Digital (whose extensive production resume includes landmark albums by Sizzla, the late Garnet Silk and multiple hit singles by Shabba Ranks) to produce Don’t Haffi Dread. This time, they played their own instruments alongside other musicians live on the album’s recording sessions.

"The riddim thing is part of Jamaican culture but with Don’t Haffi Dread, our father pulled the reins and said, that’s not how the greats do it," Gramps explains, adding, with a Jamaican inflection, "yuh don’t hear Michael Jackson say to Quincy Jones, 'Let mi vibe something on di riddim!'

"Our father always said, you have to do this at the highest level because you have great potential," Gramps continues. "Bobby trusted the process and gave us artistic freedom so Don’t Haffi Dread was a turning point: We got out our guitars, wrote songs, brought them to the studio and played/recorded them live."

Written by Gramps and Peetah, "Don’t Haffi Dread" utilizes shimmering guitar riffs that underscore the melodic sing-along chorus delivered by Peetah with innate emotional conviction and precocious wisdom that made it a 21st century reggae anthem. There are two versions of "Don’t Haffi Dread" on the album, including an exquisite acoustic guitar rendition that closes the set.

"We wrote that song in Brooklyn, it was our truth growing up in the Twelve Tribes of Israel branch of Rastafari (Bob Marley was a member), which was about bringing together Jah’s children from afar," explains Gramps. "We saw white Rastas, Asian Rastas, Rastas in New Zealand, Australia and Mexico. We knew it wasn’t about growing dreadlocks, wearing an Emperor Halie Selassie I button or even dietary laws. It was about how we lived, the love in our hearts. By sharing our truth, many people realized they didn’t have to wear dreadlocks to identify with the messages of Rastafari."

The Rastafari way of life originated in Jamaica in the 1930s, following the crowning of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I, whom Rastas recognize as the Messiah. Many early Rasta adherents wearing dreadlocks faced continuous persecution, their locks forcibly shorn, their housing settlements demolished while others were killed by authorities just for their way of life. Some listeners perceived "Don’t Haffi Dread" as insensitive to that suffering.

"The division, the uproar that took place…provided clarity like nothing else in our life," shares Mojo. "Seeing the impact of our music on a global scale, the effect it had on human lives was an epiphany; we realized that we’re here for more than just a good time and that gave us a sense of purpose. We started to understand the assignment before that term came about. The conviction and messages heard throughout our music is because of our experiences with Don’t Haffi Dread."

Rasta anthems and socially conscious statements abound on Don’t Haffi Dread. The rousing "Earthquake," is a "chant down Babylon" style tribute to Rasta elders; "Ready to Work" offers a clarion call to rise up, unify and change the world. The acoustic guitar-driven plea on "Freedom," a powerful missive that parallels the most effective songs that soundtracked the civil rights movement, features Gramps’ robust baritone, Mojo’s rapped rhymes and Una’s graceful harmonies, each complementing Peetah’s stunning vibrato rendering.

Bobby Digital’s burnished production utilizes a few premade riddims. A bubbling interpolation of the musical backing to Bob Marley’s "Bend Down Low" undergirds "Reggae Bring Back Love," an engaging celebration of the genre's positive vibrations, highlighted by Peetah’s exuberant vocals. While not originally intended for Don’t Haffi Dread, "Reggae Bring Back Love" became one of its biggest hits, as Gramps recollects.

"Bobby gave us a cassette of the riddim as we were leaving the studio. We got in the car, pushed in the cassette and just before we pulled off, Peetah started singing ‘reggae bring back love’ over the riddim. We went back inside and recorded the song in less than 10 minutes," he recalls. "Bobby was so excited," adds Una, "he said, ‘dis is why mi love dat group yah.’"

With the release of Don’t Haffi Dread, Morgan Heritage became — and has remained — one of reggae’s busiest touring outfits, taking their impassioned, spell-binding performances around the world, fronted by Peetah Morgan’s charismatic voice. Peetah’s passing is the profound loss of a gifted, generation-defining singer and a beloved brother whose spirit will inform his siblings’ future plans.

"When Lukes and Una came off the road (in 2015 and 2017, respectively) Peetah, Mojo and I carried it," Gramps muses. "Now Peetah is gone. We’re still grieving but we know Peetah would have kicked us in our butts and said, ‘gwaan and do Jah work,’ so, the legacy must continue."

Living Legends: Stephen Marley On Old Soul, Being A Role Model & The Bob Marley Biopic

Photo: Clarence Davis/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

feature

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

With debuts from major artists including Biggie and Outkast, to the apex of boom bap, the dominance of multi-producer albums, and the arrival of the South as an epicenter of hip-hop, 1994 was one of the most important years in the culture's history.

While significant attention was devoted to the celebration of hip-hop in 2023 — an acknowledgement of what is widely acknowledged as its 50th anniversary — another important anniversary in hip-hop is happening this year as well. Specifically, it’s been 30 years since 1994, when a new generation entered the music industry and set the genre on a course that in many ways continues until today.

There are many ways to look at 1994: lists of great albums (here’s a top 50 to get you started); a look back at what fans and tastemakers were actually listening to at the time; the best overlooked obscurities. But the best way to really understand why a single 365 three decades ago had such an impact is to narrow our focus to look at the important debut albums released that year.

An artist’s or group’s debut is their entry into the wider musical conversation, their first full statement about who they are and where in the landscape they see themselves. The debuts released in 1994 — which include the Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die, Nas' Illmatic and Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik from Outkast — were notable not only in their own right, but because of the insight they give us into wider trends in rap.

Read on for some of the ways that 1994's debut records demonstrated what was happening in rap at the time, and showed us the way forward.

Hip-Hop Became More Than Just An East & West Coast Thing

The debut albums that moved rap music in 1994 were geographically varied, which was important for a music scene that was still, from a national perspective, largely tied to the media centers at the coasts. Yes, there were New York artists (Biggie and Nas most notably, as well as O.C., Jeru the Damaja, the Beatnuts, and Keith Murray). The West Coast G-funk domination, which began in late 1992 with Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, continued with Dre’s step brother Warren G.

But the huge number of important debuts from other places around the country in 1994 showed that rap music had developed mature scenes in multiple cities — scenes that fans from around the country were starting to pay significant attention to.

To begin with, there was Houston. The Geto Boys were arguably the first artists from the city to gain national attention (and controversy) several years prior. By 1994, the city’s scene had expanded enough to allow a variety of notable debuts, of wildly different styles, to make their way into the marketplace.

Read more: A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

The Rap-A-Lot label that first brought the Geto Boys to the world’s attention branched out with Big Mike’s Somethin’ Serious and the Odd Squad’s Fadanuf Fa Erybody!! Both had bluesy, soulful sounds that were quickly becoming the label’s trademark — in no small part due to their main producers, N.O. Joe and Mike Dean. In addition, an entirely separate style centered around the slowed-down mixes of DJ Screw began to expand outside of the South Side with the debut release by Screwed Up Click member E.S.G.

There were also notable debut albums by artists and groups from Cleveland (Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Creepin on ah Come Up), Oakland (Saafir and Casual), and of course Atlanta — more about that last one later.

1994 Saw The Pinnacle Of Boom-Bap

Popularized by KRS-One’s 1993 album Return of the Boom Bap, the term "boom bap" started as an onomatopoeic way of referring to the sound of a standard rap drum pattern — the "boom" of a kick drum on the downbeat, followed by the "bap" of a snare on the backbeat.

The style that would grow to be associated with that name (though it was not much-used at the time) was at its apex in 1994. A handful of primarily East Coast producers and groups were beginning a new sonic conversation, using innovations like filtered bass lines while competing to see who could flip the now standard sample sources in ever-more creative ways.

Most of the producers at the height of this style — DJ Premier, Buckwild, RZA, Large Professor, Pete Rock and the Beatnuts, to name a few — worked on notable debuts that year. Premier produced all of Jeru the Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East. Buckwild helmed nearly the entirety of O.C.’s debut Word…Life. RZA was responsible for Method Man’s Tical. The Beatnuts took care of their own full-length Street Level. Easy Mo Bee and Premier both played a part in Biggie’s Ready to Die. And then there was Illmatic, which featured a veritable who’s who of production elites: Premier, L.E.S., Large Professor, Pete Rock, and Q-Tip.

The work the producers did on these records was some of the best of their respective careers. Even now, putting on tracks like O.C.’s "Time’s Up" (Buckwild), Jeru’s "Come Clean" (Premier), Meth’s "Bring the Pain" (RZA), Biggie’s "The What" (Easy Mo Bee), or Nas’ "The World Is Yours" (Pete Rock) will get heads nodding.

Major Releases Balanced Street Sounds & Commercial Appeal

"Rap is not pop/If you call it that, then stop," spit Q-Tip on 1991’s "Check the Rhime." Two years later, De La Soul were adamant that "It might blow up, but it won’t go pop." In 1994, the division between rap and pop — under attack at least since Biz Markie made something for the radio back in the ‘80s — began to collapse entirely thanks to the team of the Notorious B.I.G. and his label head and producer Sean "Puffy" Combs.

Biggie was the hardcore rhymer who wanted to impress his peers while spitting about "Party & Bulls—." Puff was the businessman who wanted his artist to sell millions and be on the radio. The result of their yin-and-yang was Ready to Die, an album that perfectly balanced these ambitions.

This template — hardcore songs like "Machine Gun Funk" for the die-hards, sing-a-longs like "Juicy" for the newly curious — is one that Big’s good friend Jay-Z would employ while climbing to his current iconic status.

Solo Stars Broke Out Of Crews

One major thing that happened in 1994 is that new artists were created not out of whole cloth, but out of existing rap crews. Warren G exploded into stardom with his debut Regulate… G Funk Era. He came out of the Death Row Records axis — he was Dre’s stepbrother, and had been in a group with a pre-fame Snoop Dogg. Across the country, Method Man sprang out of the Wu-Tang collective and within a year had his own hit single with "I’ll Be There For You/You’re All I Need To Get By."

Anyone who listened to the Odd Squad’s album could tell that there was a group member bound for solo success: Devin the Dude. Keith Murray popped out of the Def Squad. Casual came out of the Bay Area’s Hieroglyphics.

Read more: A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

This would be the model for years to come: Create a group of artists and attempt, one by one, to break them out as stars. You could see it in Roc-a-fella, Ruff Ryders, and countless other crews towards the end of the ‘90s and the beginning of the new millennium.

Multi-Producer Albums Began To Dominate

Illmatic was not the first rap album to feature multiple prominent producers. However, it quickly became the most influential. The album’s near-universal critical acclaim — it earned a perfect five-mic score in The Source — meant that its strategy of gathering all of the top production talent together for one album would quickly become the standard.

Within less than a decade, the production credits on major rap albums would begin to look nearly identical: names like the Neptunes, Timbaland, Premier, Kanye West, and the Trackmasters would pop up on album after album. By the time Jay-Z said he’d get you "bling like the Neptunes sound," it became de rigueur to have a Neptunes beat on your album, and to fill out the rest of the tracklist with other big names (and perhaps a few lesser-known ones to save money).

The South Got Something To Say

If there’s one city that can safely be said to be the center of rap music for the past decade or so, it’s Atlanta. While the ATL has had rappers of note since Shy-D and Raheem the Dream, it was a group that debuted in 1994 that really set the stage for the city’s takeover.

Outkast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was the work of two young, ambitious teenagers, along with the production collective Organized Noize. The group’s first video was directed by none other than Puffy. Biggie fell so in love with the city that he toyed with moving there.

Outkast's debut album won Best New Artist and Best New Rap of the Year at the 1995 Source Awards, though the duo of André 3000 and Big Boi walked on stage to accept their award to a chorus of boos. The disrespect only pushed André to affirm the South's place on the rap map, famously telling the audience, "The South got something to say."

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

Outkast’s success meant that they kept on making innovative albums for several more years, as did other members of their Dungeon Family crew. This brought energy and attention to the city, as did the success of Jermain Dupri’s So So Def label. Then came the "snap" movement of the 2000s, and of course trap music, which had its roots in aughts-era Atlanta artists like T.I. and producers like Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp.

But in the 2010s a new artist would make Atlanta explode, and he traced his lineage straight back to the Dungeon. Future is the first cousin of Organized Noize member Rico Wade, and was part of the so-called "second generation" of the Dungeon Family back when he went by "Meathead." His world-beating success over the past decade-plus has been a cornerstone in Atlanta’s rise to the top of the rap world. Young Thug, who has cited Future as an influence, has sparked a veritable ecosystem of sound-alikes and proteges, some of whom have themselves gone on to be major artists.

Atlanta’s reign at the top of the rap world, some theorize, may finally be coming to an end, at least in part because of police pressure. But the city has had a decade-plus run as the de facto capital of rap, and that’s thanks in no small part to Outkast.

Why 1998 Was Hip-Hop's Most Mature Year: From The Rise Of The Underground To Artist Masterworks

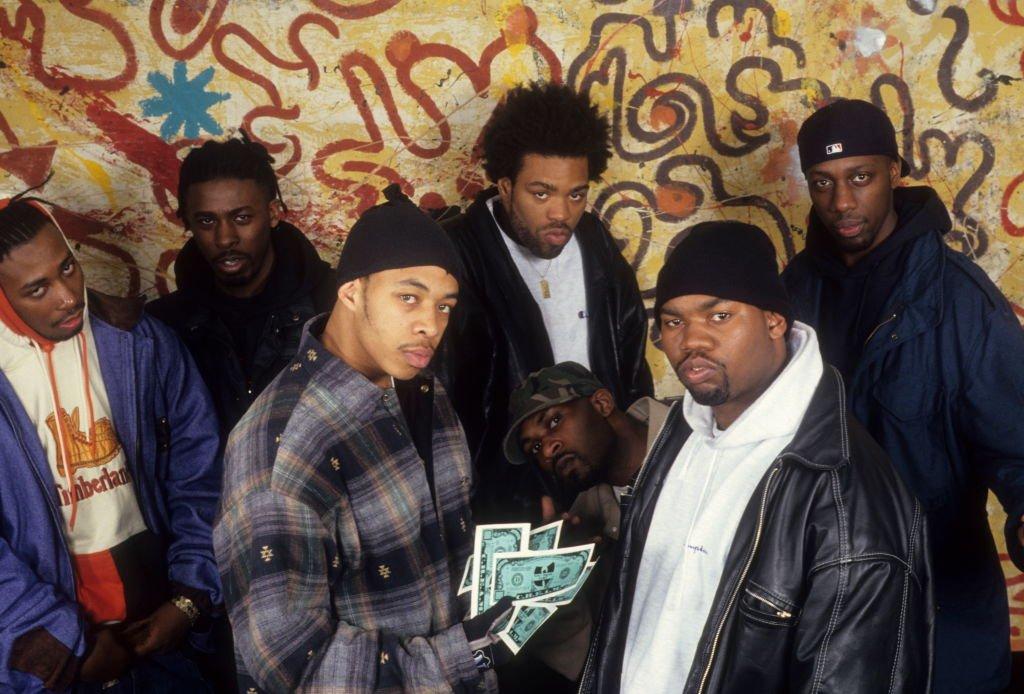

Photo: Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

feature

Nothing To F With: How 'Enter The Wu-Tang' Established One Of The Greatest Rap Groups Of All Time

In 1993, Staten Island's Wu-Tang Clan laid the ground for hardcore hip-hop acts to follow. Their weapon of choice: 'Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)' — a debut LP with an outsized impact on hip-hop and the trajectory of its members.

In the early 1990s, hip-hop was on the verge of being its broadest.

Hip-hop had grown far beyond its origins in the Bronx, as acts like Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, and De La Soul drew listeners outside New York’s five boroughs. Elsewhere, a legion of MCs from L.A., the Bay, and the South were cementing their legacies.

Amidst the plethora of sonic riches of hip-hop's golden age, Staten Island’s Wu-Tang Clan stands out. Comprised of lyrical spartans GZA, Method Man, Raekwon, Masta Killah, Ghostface Killah, Inspectah Deck, later Cappadonna, U-God, master producer RZA, and the late, charismatic force Ol’ Dirty Bastard, the group laid the ground for hardcore hip-hop acts to follow.

Their weapon of choice: 1993’s Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) — which celebrates 30 years on Nov. 9. Enter The Wu-Tang sparked a new brand of hardcore, gritty street rap that transported listeners with its dark sonic landscape.

Filled with martial arts and comic book references, loogie-spitting posse cuts, and mystifying street tales, Enter The Wu-Tang drew audiences to the borough of "Shaolin." The album's darkly-brewed beats and mixes had an amateurish charm, but all nine tracks were laced with RZA’s early musical wizardry and ear for ominous, hard-hitting instrumentals.

For every musical or budgetary limitation, Enter The Wu-Tang boasted some of the best lyrical assaults the genre has ever heard. Now-classic songs like "Da Mystery of Chessboxin’" and "Protect Ya Neck" and conjured visions of the Shaolin streets, and added to New York’s stronghold on the genre.

Unlike the more socially conscious and jazz-influenced sounds of New York rap at the time, the influential album was marked with soundbites from kung-fu flicks and sped up soul samples with an eerie, grudgeful echoe. Among the gallery of inspiring cuts, "C.R.E.A.M. (Cash Rules Everything Around Me)" features a sample of the Charmels’ 1967 song "As Long As I’ve Got You."

Despite the group’s size, every member had a stand out moment on the project. And most, with the exception of Masta Killa, have several. Method Man goes full nuclear on his self-titled track, Raekwon and Ghostface show early flashes of their collaborative magic on "Can It All Be So Simple," and the infectious charm of Ol' Dirty Bastard runs wild on "Protect Ya Neck."

The album was off-kilter in design, but Wu-Tang carved a path for hard-edged acts to follow. The album even inspired New York instrumental soul group El Michels Affair, which released their own version of the album, Enter The 37th Chamber, in 2007 in echo of the legendary beats sampled on Wu-Tang's the classic project.

Since its release, Enter The Wu-Tang has sold more than 3 million records and landed on countless all-time best album rankings. As of June 2023, the album is at the No. 27 spot on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Of All Time list. For its relatively short length, Wu-Tang Clan's debut has had an outsized impact on hip-hop — both in terms of influence and the trajectory of its members.

With Enter The Wu-Tang and their subsequent releases, Wu-Tang cornered the rap market in the 1990s. Before Wu-Tang, there were no other notable rap acts from Staten Island. While Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan and the Bronx held most of the industry’s grip, Wu-Tang helped blaze the path for acts outside of those regions to flourish.

While groups like Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, N.W.A. and Run-D.M.C. are certainly influential, the star power within Wu-Tang is unique. Between the group’s debut and follow-up album Wu-Tang Forever — which was nominated for Best Rap Album at the 1998 GRAMMYs — GZA, Method Man, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, Ol' Dirty Bastard, and others released critically acclaimed solo albums.

Method Man even received a Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group GRAMMY for Tical’s "I'll Be There For You/You're All I Need To Get By" at the 1995 GRAMMYs. Outside the accolades, Raekwon’s Only Built For Cuban Links and Ghostface’s Ironman lit up the New York streets in 1995, and GZA’s Liquid Swords remains one of the more acclaimed outings from the group’s more withdrawn characters.

While some were more commercially successful than others, they all added to the group's influence and arguably proved its distinction for best rap group of all time.

Method and New Jersey legend Redman brought their comedic chops to the big screen in How High. The pairing was like a hip-hop Cheech and Chong, and the film went on to become a cult weed movie classic. Like Meth, RZA and other members appeared in TV shows and films for decades.

In 1995, Wu-Tang Clan established the apparel brand Wu Wear, one of the first artist-inspired lines in music history. It opened the doors for hip-hop culture in retail, and inspired a global interest in Wu-Tang's simple, raw style. The group and the apparel line helped usher in the militant street style of the era, complete with baggy jeans, oversized t-shirts, Timberland boots, durags, gold fronts, sports jerseys, and puff jackets.

As the group grew in popularity, the members joined forces with business partner Oliver "Power" Grant and opened four Wu Wear stores across the country, including one on Victory Boulevard in Staten Island. The line was carried by retail giants such as Macy’s and renamed Wu-Tang Brand in 2008, and Grant discontinued the Wu-Wear line. But after RZA joined hands with Live Nation Merchandise, the brand was relaunched in 2017.

The cult interest in Wu-Tang's image continued. In 1999, Powers developed a video game centered on the group, called Wu-Tang: Shaolin Style. The 3D fighting game for PlayStation featured characters based on the group members’ stage personas and mirrored the martial arts themes in their music. They also provided voiceover work and music contributions to the four-player game.

Other artists followed Wu-Tang's blueprint in the decades since the group debuted. Acts like Mobb Deep, Nas, the Notorious B.I.G. and others adopted the hardcore rap style mastered by Wu-Tang — but none harnessed the same manpower or presence as the group over the decades. But the 2010s saw the re-emergence of rap supergroups.

In Harlem, the Diplomats and ASAP Mob captured the same collaborative and entrepreneurial spirit of Wu-Tang, but with a more varied musical approach. Out West, the Tyler, The Creator-led Odd Future surpassed the 11-member group in scale, but their work and impact haven’t matched that of the Staten Island collective.

The closest to mirror Wu-Tang was Pro Era, which adopted the classic, boom-bap sound of the '90s. The mega group also pursued an assortment of branding and entertainment ventures, and one of the group’s founders, Joey Bada$$, even played Inspectah Deck in the Hulu biographical series "Wu-Tang: An American Saga." The group’s presence also inspired future Staten Island products like Killarmy, G4 Boyz, and Cleotrapa.

Given the group’s accolades and cultural impact in the decades since their debut, it’s true: "Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothing to f— with." Its members have redefined longevity in rap by continuing to have a hand on the pulse of popular culture, both in music, film, TV, and entertainment. Few other groups have matched their successes, and as the collective continues to etch its path, there’s no telling how many more barriers they will break.

A Guide To New York Hip-Hop: Unpacking The Sound Of Rap's Birthplace From The Bronx To Staten Island

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole