Photo: Oluseyi Adegeye

Laycon

news

Herbal Tea & White Sofas: Afrorap/Afrobeats Star Laycon Explains His Love For Local Food & Why He Bans The Color Red

Nigerian Afrorap/Afrobeats artist Laycon details his tour rider in the latest edition of GRAMMY.com's Herbal Tea & White Sofas video series

We've all experienced the emotional impact of color in our lives, be it a sparkling turquoise body of water, a soft pink and orange sunset, or a painting that calms your mind. Colors also signify different meanings in different cultures and contexts, and from a young age, we identify with our favorite color(s).

For Nigerian singer/rapper Laycon, red is a color he doesn't want around him to mess with his vibes before he gets on stage, as he explains in the latest episode of Herbal Tea & White Sofas below.

The Afrorap/Afrobeats artist also discusses his love for local food while on tour, video games, and, most of all, his fan family, dubbed the iCONs.

Press Play At Home: Watch Laycon Perform An Earthy Version Of "All Over Me"

Photo: Courtesy of Michael Jason Lloyd

video

Global Spin: Watch Chike Light Up The Stage With A Technicolor Performance Of “Egwu”

Nigerian Afrobeats singer Chike celebrates the joy that music brings to the spirit in this electrifying performance of his latest single, “Egwu.”

Nigerian Afrobeats singer Chike recognizes music's ability to release inhibitions freely. Instantly, it'll improve your mood or make you want to dance — and his new track, "Egwu," is a celebration of that movement.

“Music need no permission to enter your spirit,” Chike declares in the chorus of the song. “Anywhere, anyhow, you know say you go feel/ Life is life, life is life.”

In this episode of Global Spin, watch Chike deliver a vibrant live performance of “Egwu,” made complete by his intricately patterned colorful suit and neon stage lighting.

The original version of “Egwu,” released on Dec. 15 via Brothers Records, features the late Nigerian rapper Mohbad: “I made a ton of music with a great guy, and I’m happy I can share the first one with the world,” Chike revealed on Instagram. On March 29, he dropped a remix of “Egwu” with DJ Call Me.

In another social media post, Chike announced that he will offer “an intimate musical experience as well tell stories of love, romance, and life” at his upcoming show, Apple of London’s Eye, in England this July.

Press play on the video above to watch Chike’s technicolor performance of “Egwu,” and don’t forget to keep checking back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of Global Spin.

Photo: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Megan Thee Stallion Went From "Savage" To Speechless After Winning Best New Artist In 2021

Relive the moment Megan Thee Stallion won the coveted Best New Artist honor at the 2021 GRAMMYs, where she took home three golden gramophones thanks in part to her chart-topping smash "Savage."

In 2020, Megan Thee Stallion solidified herself as one of rap's most promising new stars, thanks to her hit single "Savage." Not only was it her first No. 1 song on the Billboard Hot 100, but the "sassy, moody, nasty" single also helped Megan win three GRAMMYs in 2021.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, revisit the sentimental moment the Houston "Hottie" accepted one of those golden gramophones, for Best New Artist.

"I don't want to cry," Megan Thee Stallion said after a speechless moment at the microphone. Before starting her praises, she gave a round of applause to her fellow nominees in the category, who she called "amazing."

Along with thanking God, she also acknowledged her manager, T. Farris, for "always being with me, being by my side"; her record label, 300 Entertainment, for "always believing in me, sticking by through my craziness"; and her mother, who "always believed I could do it."

Megan Thee Stallion's "Savage" remix with Beyoncé also helped her win Best Rap Song and Best Rap Performance that night — marking the first wins in the category by a female lead rapper.

Press play on the video above to watch Megan Thee Stallion's complete acceptance speech for Best New Artist at the 2021 GRAMMY Awards, and remember to check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind.

Black Sounds Beautiful: How Megan Thee Stallion Turned Viral Fame Into A GRAMMY-Winning Rap Career

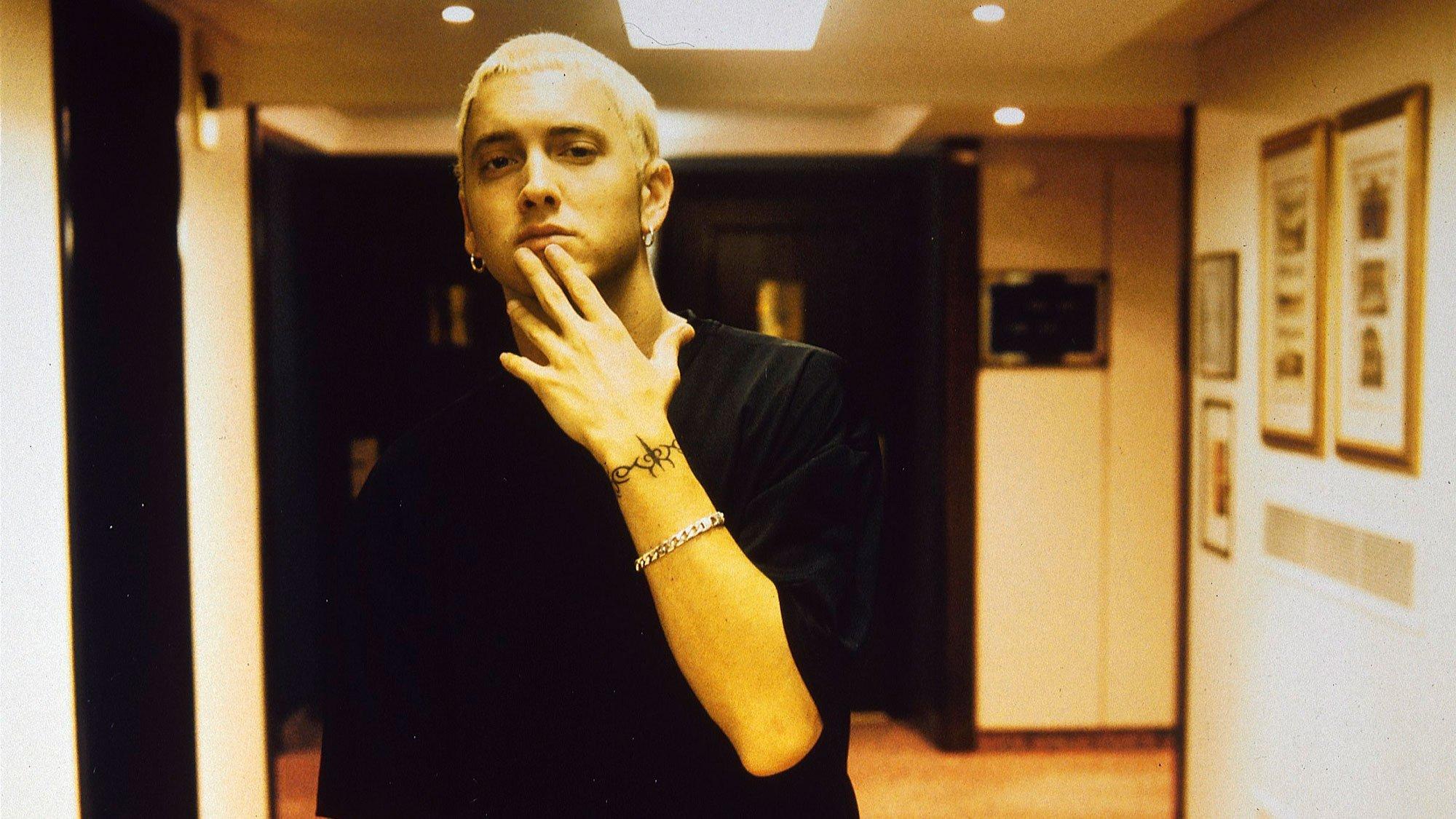

Photo: Sal Idriss/Redferns/GettyImages

list

4 Reasons Why Eminem's 'The Slim Shady LP' Is One Of The Most Influential Rap Records

Eminem’s major label debut, 'The Slim Shady LP,' turns 25 on Feb. 23. The album left an indelible imprint on hip-hop, and introduced the man who would go on to be the biggest-selling artist of any genre in the ensuing decade.

A quarter century has passed since the mainstream music world was first introduced to a bottle-blonde enfant terrible virtuoso who grabbed everyone’s attention and wouldn’t let go

But enough about Christina Aguilera.

Just kidding. Another artist also exploded into stardom in 1999 — one who would become a big enough pop star, despite not singing a note, that he would soon be feuding with Xtina. Eminem’s biting major label debut The Slim Shady LP turns 25 on Feb. 23. While it was Eminem's second release, the album was the first taste most rap fans got of the man who would go on to be the biggest-selling artist in any genre during the ensuing decade. It also left an indelible imprint on hip-hop.

The Slim Shady LP is a record of a rapper who was white (still a comparative novelty back in 1999), working class and thus seemingly from a different universe than many mainstream rappers in the "shiny suit era." And where many of those contemporaries were braggadocious, Eminem was the loser in his rhymes more often than he was the winner. In fact, he talked so much about his real-life childhood bully on the album that the bully ended up suing him.

It was also a record that played with truth and identity in ways that would become much more difficult once Em became world famous. Did he mean the outrageous things he was saying? Where were the knowing winks, and where were they absent? The guessing games that the album forced listeners to play were thrilling — and made all the more intense by his use of three personas (Marshall Mathers the person; Eminem the battle rapper; and Slim Shady the unhinged alter ego) that bled into each other.

And, of course, there was the rhyming. Eminem created a dizzying array of complicated compound rhymes and assonances, even finding time to rhyme "orange" — twice. (If you’re playing at home, he paired "foreign tools" with "orange juice" and "ignoring skill" with "orange bill.")

While the above are reason enough to revisit this classic album, pinpointing The Slim Shady LP's influence is a more complicated task. Other records from that year — releases from Jay-Z, Nas, Lil Wayne, Ludacris, and even the Ruff Ryders compilation Ryde or Die Vol. 1 — have a more direct throughline to the state of mainstream rap music today. So much of SSLP, on the other hand, is tied into Eminem’s particular personality and position. This makes Slim Shady inimitable; there aren’t many mainstream rappers complaining about their precarious minimum wage job, as Em does on "If I Had." (By the time of his next LP, Em had gone triple-platinum and couldn’t complain about that again himself.)

But there are aspects of SSLP that went on to have a major impact. Here are a few of the most important ones.

It Made Space For Different Narratives In Hip-Hop

Before Kanye rapped about working at The Gap, Eminem rapped about working at a burger joint. The Slim Shady LP opened up space for different narratives in mainstream rap music.

The Slim Shady LP didn't feature typical rags-to-riches stories, tales of living the high life or stories from the street. Instead, there were bizarre trailer-park narratives (in fact, Eminem was living in a trailer months after the record was released), admissions of suicidal ideation ("That’s why I write songs where I die at the end," he explained on "Cum on Everybody"), memories of a neglectful mother, and even a disturbing story-song about dumping the corpse of his baby’s mother, rapped to his actual child (who cameos on the song).

Marshall Mathers’ life experience was specific, of course, but every rapper has a story of their own. The fact that this one found such a wide audience demonstrated that audiences would accept tales with unique perspectives. Soon enough, popular rappers would be everything from middle-class college dropouts to theater kids and teen drama TV stars.

The Album Explored The Double-Edged Sword Of The White Rapper

Even as late in the game as 1999, being a white rapper was still a comparative novelty. There’s a reason that Em felt compelled to diss pretty much every white rapper he could think of on "Just Don’t Give a F—," and threatened to rip out Vanilla Ice’s dreadlocks on "Role Model": he didn’t want to be thought of like those guys.

"People don't have a problem with white rappers now because Eminem ended up being the greatest artist," Kanye West said in 2015. You can take the "greatest artist" designation however you like, but it’s very true that Eminem’s success meant a categorical change in the status of white rappers in the mainstream.

This turned out to be a mixed blessing. While the genre has not, as some feared, turned into a mostly-white phenomenon, America’s racial disparities are often played out in the way white rappers are treated. Sales aside, they have more room to maneuver artistically — playing with different genres while insulting rap a la Post Malone, or even changing styles completely like Machine Gun Kelly — to commercial approbation. Black artists who attempt similar moves are frequently met with skepticism or disinterest (see André 3000’s New Blue Sun rollout, which was largely spent explaining why the album features no rapping).

Sales are worth speaking about, too. As Eminem has repeatedly said in song, no small amount of his popularity comes from his race — from the fact that white audiences could finally buy music from a rapper who looked like them. This was, as he has also bemusedly noted, the exact opposite of how his whiteness worked for him before his fame, when it was a barrier to being taken seriously as a rapper.

For better, worse, or somewhere in between, the sheer volume of white rappers who are currently in the mainstream is largely traceable to the world-beating success of The Slim Shady LP.

It Was Headed Towards An Odd Future

SSLP laid groundwork for the next generation of unconventional rappers, including Tyler, the Creator.

Tyler is a huge Eminem fan. He’s said that listening to Em’s SSLP follow-up The Marshall Mathers LP was "how I learned to rap." And he’s noted that Em’s Relapse was "one of the greatest albums to me."

"I just wanted to rap like Eminem on my first two albums," he once told GQ. More than flow, the idea of shocking people, being alternately angry and vulnerable, and playing with audience reaction is reflected heavily on Tyler’s first two albums, Goblin and Wolf. That is the template The Slim Shady LP set up. While Tyler may have graduated out of that world and moved on to more mature things, it was following Em’s template that first gained him wide notice.

Eminem Brought Heat To Cold Detroit

The only guest artist to spit a verse on The Slim Shady LP is Royce da 5’9". This set the template for the next few years of Eminem’s career: Detroit, and especially his pre-fame crew from that city, would be his focus. There was his duo with Royce, Bad Meets Evil, whose pre-SSLP single of "Nuttin’ to Do"/"Scary Movies" would get renewed attention once those same two rappers had a duet, smartly titled "Bad Meets Evil," appear on a triple-platinum album. And of course there was the group D12, five Detroit rappers including his best friend Proof, with whom Eminem would release a whole album at the height of his fame.

This was not the only mainstream rap attention Detroit received in the late 1990s. For one thing, legendary producer James "J Dilla" Yancey, was a native of the city. But Eminem’s explosion helped make way for rappers in the city, even ones he didn’t know personally, to get attention.

The after-effects of the Eminem tsunami can still be seen. Just look at the rise of so-called "scam rap" over the past few years. Or the success of artists like Babyface Ray, Kash Doll, 42 Dugg, and Veeze. They may owe little to Em artistically, but they admit that he’s done great things for the city — even if they may wish he was a little less reclusive these days.

Is Eminem's "Stan" Based On A True Story? 10 Facts You Didn't Know About The GRAMMY-Winning Rapper

Photo: Dan Mbonu

news

"Wake Up" With Bloody Civilian: How Owning Her Perspective & The Support Of Women Allowed The Afrobeats Artist To Thrive

The Nigerian singer and songwriter contributed to the GRAMMY-nominated 'Black Panther: Wakanda Forever' soundtrack — but Bloody Civilian's contributions to the ever-expanding world of Afrobeats go far beyond the Marvel Universe.

Emoseh Angela Khamofu began crafting beats at age 12 and wrote her first song on a piece of tissue paper. This innocuous interest quickly developed an obsession with music that, later, propelled her to incredible heights.

Within a year, the 25-year-old singer and songwriter now known as Bloody Civilian released two EPs: Anger Management and a remixed version, Anger Management: At Least We Tried, and signed to 0270 Def Jam. Her song "Wake Up" featuring Rema is on the GRAMMY-nominated Black Panther: Wakanda Forever soundtrack.

Bloody understood early on that she'd have to approach her career holistically. Across her body of work, Bloody uses her "unparalleled” storytelling ability and lyrical dexterity to take listeners through personal and societal hardships.

The moniker Bloody Civilian refers to the struggles encapsulated by the often-derogatory term directed at Nigerian citizens by the military, and is also a poignant homage to a challenging chapter in her life. Born into a religious family in northern Nigeria, a young Bloody and her family relocated to the national capital, Abuja, due to unrest; she later moved to Lagos to pursue music.

"Growing up as a female in Nigeria is unnecessarily hard. It's unnecessarily complicated, especially when you do something unconventional," Bloody Civilian tells GRAMMY.com. "I had to fight for a lot of the leniences that I experienced."

Ahead of the 2024 GRAMMYs, Bloody Civilian discusses pursuing music as a girl in a religious home, becoming a serial entrepreneur just to buy recording equipment, and the art of production.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You gravitated toward music started at such a young age. What was it like charting a path that went against the pious, conservative norm you were born into?

It was a difficult process. Stopping making a beat to go wash plates just doesn't bang. As a Nigerian female, my brothers don't have the same home experience as I did. They had enough time to cultivate various skills and for me — if not for the level of obsession that I had for what I was doing — this could have been impossible. The chances of you being distracted at home as a female, is way higher than as a male.

Your dad played as a bassist in a band. Surely, you wanting to be an artist could have been seen as following in his footsteps…

But he's a man, so no one told him what to do. Whereas in my case, having that same creative hunger as the person that gave birth to me wasn't an easy journey. I had to fight for a lot of the leniences that I experienced. I had to rent things out and sell merch, to raise enough funding to buy equipment. I was a serial entrepreneur due to circumstance.

I understand that your parents didn't support you financially until further into your career. What was their reaction to you doing all you had to do to pursue what they probably thought was a hobby?

At the beginning, the little wins that I'd get and the little bit of popularity — people in the church saying "We saw her content from my daughter's phone" or one thing or the other — I think that's when my parents had an element of there's something to be proud of rather than be ashamed of me as a daughter. It became easier along the way.

But it definitely was tough. Very tough. Especially production; beat making, they really couldn't fathom or understand. It came to a point where they understood that I wanted to become a singer but this beat making thing, why not go and work with a producer?

And did they take you to a producer?

Yes, the first producer my mother took me to and paid for a session, I did most of the work. And I could tell that it wasn't easy taking instructions from a 12-year-old. I could see how hard it was. But I think in that session, him trying the things I asked for and seeing that it worked out, and he'd kind of give me this look of she knows.

I went to the studio, didn't know much. I was fascinated by the mic — stared at it for, like, a while [laughs]. I still remember looking around. The deafening sound of a studio; I was just taken back by it. Everything was just so fancy. Production started out as equal parts bad belle [Nigerian slang for resentful, jealous or bitter] and equal parts necessity.

**On "Family Meeting” off Anger Management, you sing: "Before you return me back to God, I think I'm going to pack my s— and run” hinting at how you moved to Lagos. Did you really run to Lagos?**

Something like that, yeah. I had to leave Abuja…urgently. And ending up in Lagos was definitely something that was a do or die, but not necessarily die. More like do or nothing.

It's been two years since you moved to Lagos from Abuja. How much of an adjustment was that move for you?

When I came, I was slightly more impressionable and very gullible. Typical JJC ["Johnny just come," a Nigerian term for a newbie/ novice to a place or situation]. And that's something about my psychology that really shocks me. I have a chameleon-like ability to evolve over a short period of time. The last two years of being in Lagos, I'm almost unrecognizable to my old self.

When I came to Lagos, I was the person I needed to be. I connected with different creatives. I went to people with experience and a good heart to get advice. I knew where to go to listen, I knew where to go to record. I knew different things because I explored a lot. And the reason I'm not in a screwed up situation is that I went and got advice from Osagie [Osarenz, Director of A&R and Operations at ONErpm]. It is because of her that I didn't sign a contract that I'll be crying about today. She basically told me "don’t sign anything, make sure you show me."

Honestly, I was just lucky. I didn't have anything that differentiated me from anyone. I'm just lucky I met the people I met and was coincidentally lucky to listen when they spoke.

How did you get signed to 0270 Def Jam?

I got signed off of a demo tape. A bunch of songs I wanted to sell to other artists. I wrote "How To Kill A Man" to sell [and] a lot of the tracks on the EP [like] "Escapism" to sell. I wanted to kind of just write for other people. But because of the way I put the tracks together, people felt, this is an EP and you're an artist.

I just kept getting nudged to take the artist route. And I always wanted to be an artist even prior to coming to Lagos because when I write songs, I write from my perspective; it's my voice, it's my music. Someone else could sing it out, but it's my story. I was pretty ready to become a writer-producer, but the way things panned out, [the EP] kind of sent my name around town.

But two women put me here. Remove those two women, I'm in the trenches.

The second woman was in the creative scene, high up. She was at an event with top executives and sent my music to multiple people, hoping a few would respond. Well, pretty much everyone she sent it to was sending me offers. My life changed [snaps fingers] in that instance. That's when I shut down all conversations with everybody in Lagos. I said, "I'm definitely not signing my deal here" because it was hard to get people to see the value in what I was doing. We're here today because two women decided let me clear some time in my schedule to talk to this girl.

Take us on the journey of how your song "Wake Up," which is featured on the GRAMMY-nominated Black Panther: Wakanda Forever album, came to be.

Since the film is about Africa and had a very women-led cast, they really wanted to portray the strength of women in general. So, even with the way they made the music, they wanted it to involve women creatives. They wanted female songwriters, producers, and when you run a search for female producers in Nigeria, there's very few that come up. I just happened to be one of them.

Got in the studio, met [composer] Ludwig [Göransson], played beats for him. He took the one that you hear and worked on it, added some cool synths and stuff. They had brought instrumentalists, and they spent a year sampling traditional music, so they pretty much had a bunch of sounds that he was playing with. He took it from what the demo beat was to what it is now.

What ranks higher for you, producing or creating your own music?

Producing, then music. You wouldn't even have me if I couldn't produce. Maybe now in Nigeria, you can go 'round and find people that are experimenting outside of the norms [of conventional music]. Now it's a better time. These songs were made years ago. I was there before everyone else.

My first viral video on Instagram was because I carried a Travis Scott-type melody loop, and I put on Afrodrums. It went viral because, one, no one does this combo — and then a girl did it. I had a hunger; I wanted to create a specific sonic, and I was just struggling to piece it together.

I can tell you that production came first. It was when I put that part of my artistry together that my lyrics started to shine.

You've spent years crafting your sound we hear today. There's a trend of Afrobeats artists trying to break away from the label and form subgenres, like Burna Boy with Afro fusion and Rema with Afro rave. Is "Afro-escapism" your attempt at that break away?

[Laughs.] Why are they attacking me with that Afro-escapism? It's weird, I love the different Afro subgenres: Afro-depression, Afro-escapism, Afro-sapa. There are no bad songs. I hate it that we eat away at each other.

There's so many styles of intelligence. You can't come and say this person's music is more deep or profound than another person's music. Everyone has their perspective, their language, but the content of what they're saying has value. As listeners, we should just never forget that it is important for us to also train ourselves to be good listeners for the music to thrive.

The cover art for Anger Management represented you being sort of alone, but Anger Management: At Least We Tried looks different with bright colors. Is it safe to say that this depiction represents how you feel now?

Yeah, it is. Being the "number one breakout artist of 2023" [laughs] made me see that Nigerian music is in trouble. [My team] worked hard, but it definitely just lets you see how hard it is to break in new acts. The way I see it, if you're not expressing yourself and you're not being authentically yourself, whatever you stand for, it's gonna be harder now than ever.

Looking back at [Anger Management], it wasn't really a happy time. But despite that, on-air-personalities literally reached out to me and were playing the music before we had worked out business and everything. It was very organic.

With a lot of my accomplishments, I usually have to be made to understand the worth of it because it doesn't really dawn on me. I just felt this EP was made with me in a sunken place. I'm no longer in a sunken place, but I want to remix my EP.

I'm feeling happy, excited. And it feels like a point in my life where so much can happen. It was also the first time people would see me interact with other artists, which for some reason fans like to see.