Photo: Chris Phelps

interview

Jessi Colter's New Album 'Edge Of Forever' Is Timeless In Every Sense Of The Word

On 'Edge of Forever,' the 80-year-old outlaw country star doesn't sound like an elder stateswoman. Her latest could have been released in 1973 or 2013.

As one of the lone women in the outlaw country milieu, Jessi Colter has navigated the music industry with grace for more than half a century — through false starts, lulls, and the death of her husband and collaborator, Waylon Jennings.

But while some living legends can feel a touch frozen in time, Colter is constantly in motion.

"We've just returned home a few days before the Hall of Fame performance, and my house is a wreck," she reports to GRAMMY.com, upon landing back in her Arizona climes. During a brief conversation, she's speed-eating lunch and jumping in a car; she even suspects this interviewer was multitasking as well. ("Are you doing dishes?" Colter inquires, in response to an errant clank over the line.)

That consistent movement — of body, of creative practice — allowed Colter to cook up one of her most inspired albums. Edge of Forever — produced by GRAMMY nominee Margo Price, and mixed by Colter's son, three-time GRAMMY winner and five-time nominee Shooter Jennings.

Backed by Price's crack band, tunes like "Standing on the Edge of Forever," "Lost Love Song" and "Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus" crackle with potency — and have all of the impact of her early work, prior to all these spins around the sun.

But this timelessness doesn't mean it's simply retro, or '70s; it moves through time. Edge of Forever couldn't have happened without the lumps she's taken in the country machine, or the jubilations.

Furthermore, it proves that the hitmaker behind "I'm Not Lisa" and "What's Happened to Blue Eyes" back in '75 remains a force — as a feisty, vital country-music matriarch. Below, Colter chats with GRAMMY.com about Edge of Forever, and what's on the other side.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Congrats on the release of Edge of Forever. I think the word "timeless" gets thrown around a little too much, but the description fits here.

I had one fellow, I asked him how old he was. I figured he was 20 or 28 and he was 60. I think it was [for] Variety. When I first talked to him. And he said it just has such a feeling that it takes him back to the '70s, and I wasn't sure what he meant exactly. I just am who I am and that's who I'll always be.

But anyway, he loved it. He said it really felt, for him, comfortable. And I understand what he's saying. There's a whole lot out there that's not so comfortable.

Interesting. What do you hope people take away from your music?

Well, certainly that, and I hope I communicate with feelings they've had. I loved it on "I'm Not Lisa," when the little girls would send me tapes of themselves singing it. I thought I have communicated, because when I write it's very inward of my experience or somebody really close to me and so forth. So that's how it goes.

Take us back to your early conception of Edge of Forever — the spark that lit a flame.

Well, I had songs. And I became acquainted with Margo, and she helped me out on a Facebook flash [giveaway] of my book An Outlaw and a Lady, for Harper Collins, that I wrote with David Ritz.

And this was 2015. She was pregnant with Ramona when we cut this album and she was about to have the baby. So as far as the genesis, it took two or three visits together, and [her husband] Jeremy [Ivey] and she both intimated that they would love to see me do an album.

It was years later that we did it. And we did it quickly and directly, because she was about to have her baby. And so it didn't take the kind of time that I'd taken on other albums, but it's taken time to wind its path to the yellow brick road, which seems to be Appalachia Records, who she'd worked with before.

[Label owner Loney Hutchins is] great to work with, and I've never worked with a small label that worked with other indies. But anyway, they've been terrific. And so we just kind of were drawn to each other. And I had these songs that she reacted to, and then there was a couple others, then one written on the spot.

And so it just happened and now it's taken the legal teams, and the manager — this and that, so forth. Anyway, it's worked out. It worked its way to here.

Can you talk about your dynamic with Margo and Shooter?

Yeah, it's fantastic. It's easy. I've worked with Shooter before on The Passion of the Christ, where he wrote on the spot with me. It was an album that went with The Passion of the Christ; It wasn't a soundtrack.

We wrote a song called "Please Carry Me Home." If you haven't heard it, try it, because we wrote it and he produced it on the spot. Then [my daughter] Jennifer [or Jenni Eddy] and I actually wrote "Secret Place," which is on this album, a number of years ago.

Waylon was still with us, and he heard that song — and he didn't often say just this, but he said, "You've got to do that." And it's just been in my pocket.

Often, artists keep songs that inspire them. They don't use them until the time is right. And so there were a number of songs that I had been holding onto. "Lost Love Song," "Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus." I totally rewrote that spiritual except the bridge.

Anyway, the dynamic was fantastic with Margo, with Shooter, with Jennifer Eddy Jennings, my daughter; her father is Duane Eddy. Waylon was a wonderful father to her. So, it's been a gift; the whole thing has been a gift for me.

Working with Jenni Eddy must have a gift among gifts.

Oh, yes. She's so gifted and a great singer. She just hasn't come into the public yet, but she's working on a number of things.

And Struggle Jennings, my grandson, recorded a great album with her called Spiritual Warfare, where Struggle is rapping. [Jenni] sings, and she wrote the songs, and then he raps. And it's interesting.

I don't know what she'll end up doing. Her voice is much more melodic than mine, and she sings beautifully with me. It would be worth working to her and Jenny Lynn Young accompany me, if and when I perform. It''s magnetic, the whole thing.

As a singer/songwriter myself, even something I wrote a year ago can feel alien to me today. Can you talk about reacquainting yourself with tunes from many years ago?

I understand that, but if you love a song to start with, you'll always love it. And so that's how it went with me.

"Maybe You Should Have Been Listening" was one of Waylon's favorites on my classic albums, and "With or Without You" was something I wrote a number of years back for a girlfriend of mine who went through being stood up by a well-known man right before their wedding.

Little Stevie Van Zandt loved that song: "With or without you/ I'll go on alone… And like Bob Dylan said, if it's not right, it must be wrong." I love that. And if people would remember that. "Angel in the Fire" I wrote some time ago. I love it every time I sing it, with Lisa Kristofferson in mind.

"Lost Love Song" was a song that I held in my pocket to inspire me. It is talking about the prison of love. I never have been able to find who wrote it. He may be living, he may not, because I had this years before Waylon went, which was 2002.

"Hard On Easy Street" was great fun. I did it on an album that I [do not] yet have the right to publish. Never came out. It's a great song. "I Wanna Be With You" is always an upper, and percussionists particularly love that song because it's such a rhythm.

"Standing on the Edge of Forever" was a new song I wrote in the last 10 years [about]a relationship that just won't come together, and that's what that's about. But it's also, as Lenny Kaye edged me on to say, This is it, either or. It's that time you come to and it's enough of whatever it is, get on or get off.

"Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus" — oh, that's one of the great songs of all time. James Cleveland wrote it, but I rewrote it. But I don't find to ever get any income from that.It's just a great song talking about how it is. If you're going to do right, you may be alone.

"Fine Wine", Jennifer wrote that with some accompaniment by Margo, and it's talking about early widowhood. And it was how it was maybe four years ago, even though that was a 16-year mark of loss for me, I had been alone for 16 years when I said I'm open for love.

And as things work out and good things happen, I met my current husband, a rancher, horseman from Wyoming, and took it a few years to kind of get to know each other, but we're having a good time.

With Edge of Forever out in the world, what are you looking forward to in the near future?

Right now, I'm looking forward to a documentary I've been working with [a production team] on for eight years. It's called They Called Us Outlaws. Eric Gaberman, partnering with the [Country Music] Hall of Fame did so much research on our time — and the sentinel turn of music in our generation — that I said yes.

[It's a] film coming with so much fact, and then he brings it into the present. Those that have a mindset more to try to do what they wrote and how they did it. And the "outlaws" was more or less a branding in a time that branding wasn't even known, and it stuck. So, it's been useful to a lot of new artists coming with new sounds.

*Jessi Colter. Photo: Chris Phelps*

You've lived through so many epochs in the music industry, When you look back on your decades in the industry — all the triumphs and losses — what do you think of?

Well, there have certainly been chances. Don Was ran into us at the Crazy Horse in Orange County. He showed up in the dark, and scared me because I didn't know who he was. While Waylon was doing the show, and he just talked a minute and said, "You know what, Jessi? The '70s were so much fun."

There was something about that that was the beginning of a lot, but it was the ending of something. It was a major turn with the University in Austin having been exposed to a lot of rock. So when Waylon and Willie came with their sound there, they reacted more like a rock group — Waylon did not cross boundaries in those days. You didn't do it. The companies wouldn't allow it.

So, it was an amazing procedure that took place and we were so glad to be part of it. Since then, it's kind of rolled with the punches, and Americana has gotten its feet.

And Shooter has been miraculous in some of the things that he's yielded already. But Waylon and he both don't go for prizes. They do help you, but you have to have that creative want to.

When he was 16, he didn't want a car; he wanted Pro Tools. So, he started early on his path and is doing great. He was a little before his time in performance and then working through being the son of Waylon Jennings, he worked through that and did great.

He loved his father dearly, and he now is a great spokesman for his father, which I love. But all in all, we'll just have to wait and see what's going to happen around the corner.

On You're The One, Rhiannon Giddens' Craft Finds A Natural Outgrowth: Songwriting

Photo: by THOMAS CRABTREE

interview

Vincent Neil Emerson Enters The 'Golden Crystal Kingdom' Of Gut-Punching Country Music

Inspired by several years of life changes, Vincent Neil Emerson's new album, 'The Golden Crystal Kingdom,' tells Western stories that honor his past while keeping a steady eye on the future.

Growing up in Van Zandt county, Texas, it would be easy to say country singer/songwriter Vincent Neil Emerson was bound to follow in Townes Van Zandt’s footsteps, after whose family the county is named. But to Emerson, it never felt like a sure thing. It still doesn’t.

"I don't think I really had a defining moment of that feeling like, oh, I can do this, because everything's so uncertain. It's like anything in life, nothing is really guaranteed," he says.

Emerson’s nuanced, honest songwriting often draws comparisons to Van Zandt, John Prine, and Guy Clark and has earned his songs appearances on "Reservation Dogs" and "Yellowstone." His latest album, The Golden Crystal Kingdom, is produced by Shooter Jennings and out Nov. 10.

Emerging from several years of life changes — fatherhood, marriage, and a new band — Emerson crafted an album of Western stories that serve as both an ode to how he got here and a declaration of intent for the future. He deftly tackles Indigenous history (Emerson is Choctaw-Apache), reflects on how we live and what we value, and explores the life lessons in love, loss and disenfranchisement.

Drawing inspiration from across the music spectrum – he’s a huge Bob Dylan, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Neil Young fan – Emerson’s careful not to sample too much from any one style, choosing instead to focus on honesty, and letting the music serve the story. The result is a set of moving, stripped-down songs, each of which illuminate a small slice of the human experience.

Emerson started his singer/songwriter career as a teenager, getting himself a long-forgotten crappy guitar and jumping in feet first – "I learned three chords and I tried to write a song immediately." Quickly he started busking and attending open mics, gradually building a repertoire of folk song covers and eventually writing the songs for his first album, Fried Chicken & Evil Women.

At the release of his sophomore album, Vincent Neil Emerson, fellow Texas songwriter and producer Rodney Crowell summed up Emerson’s potential to carry on the Texas singer/songwriter tradition: "It’s possible young Vincent will plant the flag of his forbearers firmly in the consciousness of a whole new generation." As Emerson sings in the title track from his latest, The Golden Crystal Kingdom, "heavy is the head that wears the crown."

But it’s not a crown Emerson’s ever going to take for granted. Instead, he’s focused on making good music that’s honest and relatable. Ahead of his album release, Emerson spoke with GRAMMY.com about finding his voice, the importance of Indigenous stories, writing love songs, and artistic freedom.

The Golden Crystal Kingdom is an interesting name for an album, and for a track. I'm curious where that came from.

I'd rather just leave it up to speculation. I don't want to tell people what it means, let's leave some mystery there. I just want people to have their own opinions about it and not be swayed by what I say about it.

Okay, I can respect that. Can you tell me about writing the title track?

I wanted to write a song as my dedication to the dance halls and honkytonks that I've played over the years. A lot of bad times, actually. But some good times, too.

You said on Instagram recently that you write from the position of somebody who doesn't fit in, because that's how you feel.

I felt like that most of my life. I feel that way a lot of the time. So I'm trying to write from a place that's honest. If you're not honest, some people can never relate to you. I just want to make good art. And the best way I've tried to do that is to be honest about life.

Tell me a little bit about writing "The Man from Uvalde." It's a pretty intense song.

Well I was watching the news [of the school shooting in Uvalde, TX], I was living in San Antonio at the time. And that was right up the road from our house. The melody just kind of jumped out of nowhere, and the lyrics just started coming to me.

I saw what happened to those children. I thought about my son, it’s just a pit in my stomach. I was terrified at the thought of that, and I could only imagine what the parents of those children that lost their lives felt.

Yeah, of course. Has anything changed for you in writing songs since becoming a dad?

I guess not. I'm still trying to figure out how to write good songs.

I think you're doing okay. Speaking of which, what’s the story behind "Little Wolf’s Invincible Yellow Medicine Paint," the album’s last track?

My wife brought home this stack of old Western comics from the ‘60s. And I read a story about Little Wolf's invincible yellow paint in there. Basically, there was a medicine man who was told that he needed to motivate these warriors and try to convince them to go into battle against people who had guns. They knew they were going to die if they went, because they did not have guns.

He came up with this yellow paint and he said that no arrow would pierce you, no bullet will pierce you; if you wear this paint, you'll be protected. I don't remember the rest of the story off the top of my head, but that's where I stopped writing. I was like, I don't want to paint the end. But I do say in the song "everything is dead," like 12 times.

There's a line in there that says, "keep your prayers that I find my worthy death." There's this idea of a warrior needs like a worthy death, and I literally meant, take your prayers back. I don't need your prayers for that s—.

It's a gut punch of a concept, right? Because we know how that story ends. You don't have to put it in the song.

Then there's the whole idea of being sold something from one perspective, we're being sold this thing that's really not going to help us. And on the other side, maybe it did help. Who knows?

It meant a lot more to me when we made the music video. We had an Indian relay racer named Sharmaine Weed. It feels like it's more motivational — "I have been down but I'm not out yet." I wish I could take credit for [that casting]. But it was actually Mike Vanata from Western AF. It's sort of an old West song, but it really brought it around into modern times putting that imagery behind it.

Over the last couple of years you've gotten more comfortable or more vocal about being Indigenous yourself. Was it just natural to start talking about it more, or was there some motivation there?

Well, I'm 31 years old now. When I first started playing music and playing shows, I was young, I was in my early 20s. People change and grow up and mature, and I definitely have over the years. I wrote all those songs off my first record when I was 22, 23. And I recorded them when I was 25. And finally put it out when I was 27. And I'm still carrying around who I used to be in those old songs.

I'm ashamed to say, but I didn't really care as much about where I came from. I just wanted to go somewhere and be someone else. As I got older, I started talking to my grandmother about things and remembering where we come from and going to powwows growing up and stuff like that. I think it's important to hold on to that. I don't want to be erased. I don't want my family history or my culture to be lost or forgotten. So that's a big reason why I embraced who I am.

You’re getting put on some lists of Indigenous country musicians. Country music is notoriously really, really slow to change. And even when it starts to open up, there's often setbacks. What would you like to see from music in terms of representation and inclusion?

I feel like it’s less of a country album and more of a rock 'n' roll album. There's still some country songs on the album, but I've always loved country music.

There's not enough diversity or inclusion. And there's a lot of great, great Indians in country music and music in general. And we don't really see a lot of those people at the front. It would be nice to see more of that.

What are some of the most rock songs on this album for you?

"Little Wolf’s Invincible Yellow Medicine Paint" definitely feels like a rock 'n' roll song to me. "Hang Your Head Down Low." I was listening to a lot of Dylan at the time. And I wanted to write a Highway 61 Revisited kind of sound. It just depends on how we play it live too. Because sometimes my guitar player will play more country licks on the Telecaster over the song. And all of a sudden, it turns into a fast paced country song.

I just stopped worrying about what genre it is and just started writing whatever feels natural and good.

I sometimes think journalists and PR people are the only ones who think about this anymore.

Well, genre is very helpful for categorizing things, for promoting things and reaching certain audiences. But there’s certain combinations that come along with each genre of music and certain things that people expect. That’s why I think it gets dangerous for the art, for the artists.

"Dangerous" is a really interesting concept. Can you say a little bit more about that?

Well, I think it's dangerous to the artists, but it's also dangerous to the art. If you’re not allowing people to express themselves or if you're giving them pushback or putting someone down for moving in a certain direction or doing a certain thing that you don't like it hurts. It doesn’t belong. It feels like you're killing off parts of people.

There's a couple of love songs on this album too. And I'm curious where those come from. You just got married, right?

Yeah, I just got married. "On the Banks of the Guadalupe," I wrote that for my wife. It's hard to write love songs. It's hard to write like that and not feel like I'm sounding cheesy.

It sounds incredibly hard. I think it would be a lot easier to write songs about characters, like the album’s open track "Time of the Rambler."

I wrote that song in Shooter Jennings’ basement, while we were recording the album. It was maybe a couple of days in, and I stayed in his basement of his house. And he has a nice room setup down there, you can see the highway from the basement. I was just looking at all these cars and driving up and down the highway. And that's where some of the lines came from.

Where do you find the characters you write about?

Just from how I feel and the things that I've been through and done. Sometimes just taking inspiration from things I've seen and just hanging out in the back of my mind somewhere. I might have seen a movie or maybe I've met someone firsthand who, and told me about some experiences they had, it's all over the place.

Where do you see yourself fitting in that Texas singer/songwriter tradition?

I'm okay with people lumping me in with those guys, that's great. I love all that stuff. I don't think that it's fair to compare any artist against another. Art is so subjective, and it's personal and so open to interpretation. But it's nice to be mentioned in the same sentences as guys like Townes Van Zandt. I'd hate to be compared to him because he's an incredible writer. And he did so much. It's an honor. To have a legendary guy like [Rodney Crowell] come at you and say some really nice things, it just meant so much.

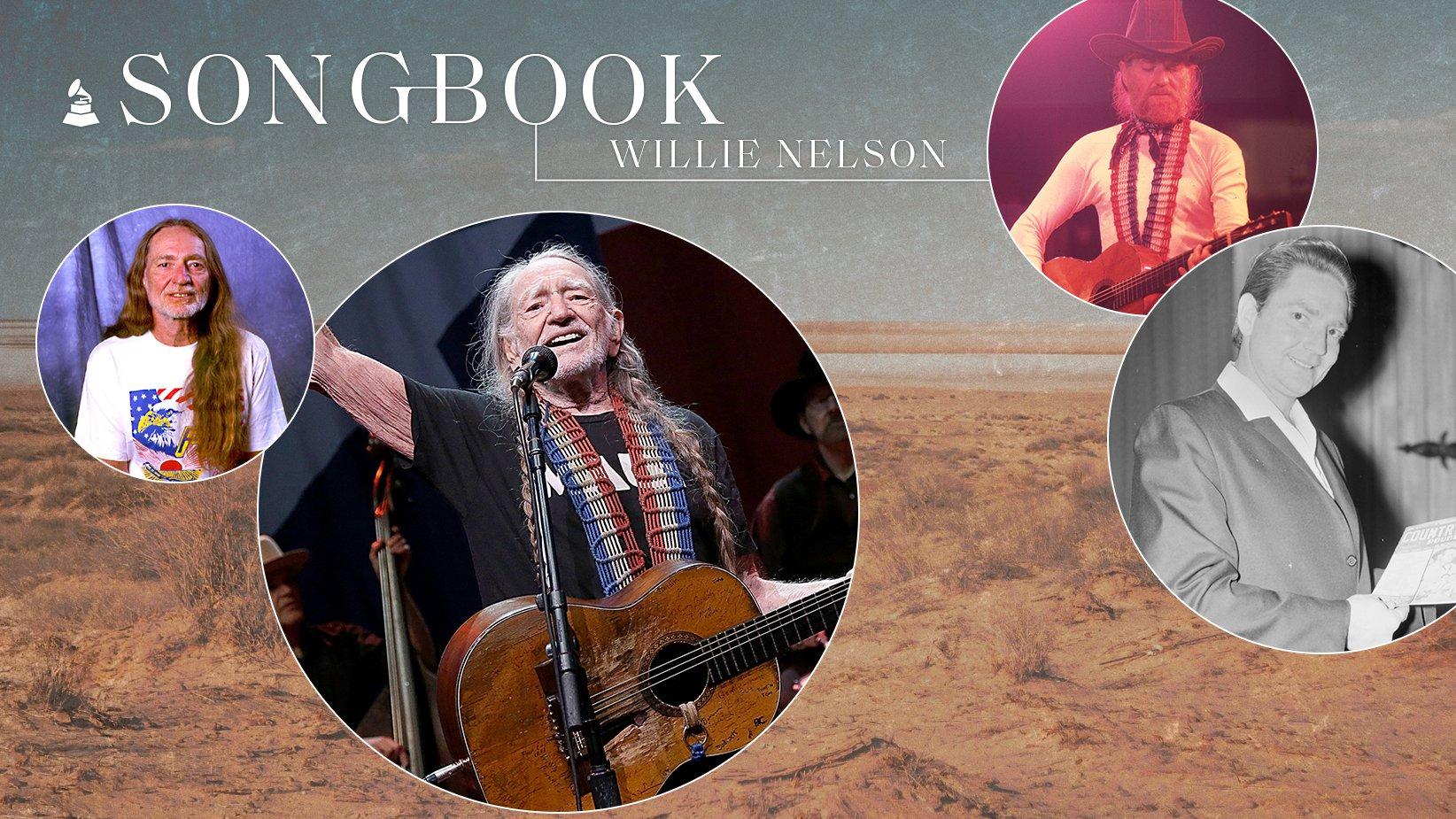

Photos (L-R): Paul Natkin/WireImage, Gary Miller/Getty Images, Chris Walter/WireImage, Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

feature

Songbook: A Guide To Willie Nelson's Voluminous Discography, From Outlaw Country To Jazzy Material & Beyond

Prodigious songwriter, interpreter and national treasure Willie Nelson has released dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on who you ask. Still, a few key entryways and rabbit holes can help you get a handle on this foundational country figure.

Presented by GRAMMY.com, Songbook is an editorial series and hub for music discovery that dives into a legendary artist's discography and art in whole — from songs to albums to music films and videos and beyond.

Cue up almost any Willie Nelson performance from the last 10 years, and you'll find something intriguing. Many other country greats are tight and precise onstage; Nelson is decidedly not.

While his Family band easily catches a groove on well-worn classics like "Family Bible," "Crazy" and "Funny How Time Slips Away," our permanently bandana-ed and pigtailed protagonist is attuned to deeper and stranger rhythmic dimensions. A Willie Nelson show is a particular kind of miasma — at times, it coheres; at times, it hovers almost beatlessly.

Sometimes, Nelson’s famously jazz-inflected syncopation threatens to swing him off the road — he'll strike his famously battered and weathered classical guitar, Trigger, at a moment that seems jarringly off the beat. His light and flinty voice has developed distinguished cracks and fissures with age. But if you're disappointed by his relative lack of polish, you're not just missing the point — you're missing the beauty.

First, nobody has ever picked up a guitar and sang a song like Nelson. The gods only made one of him, and the most fabulously expensive guitar on the market could never sound like Trigger. Second, the soul of country music is impactful storytelling and direct emotional transference, and nobody wields those twin abilities like Nelson, both as a songwriter and interpreter.

Indeed, without him as its cockeyed embodiment and one of its foundational figures, the world of country music would be unrecognizable — period.

Despite a few minor off-ramps during his almost seven-decade career, Nelson has built an astonishing body of work not via overhauling or reinvention, but becoming more himself every year. With every release, he digs deeper into his time-tested toolbox and aesthetic — often to heartening, comforting, and wizening results.

You don't approach the recently released A Beautiful Time, Nelson's fourth album in two years, for left turns; you do so because you want to know what the Beatles' "With a Little Help From My Friends" and Leonard Cohen's "Tower of Song" mean to him — as well as the state of his songwriting.

While the resin-caked hayseed vibe Nelson has embraced since the '70s may be a far cry from his crop-topped beginnings, you can drop the needle on any decade and hear an essentially unchanged artist and person. Whether he's channeling George Gershwin and crooning Broadway tunes, or running from the IRS on record — or even making reggae-inspired music, as on 1995's Countryman — Willie is Willie is Willie.

That said, the 10-time GRAMMY winner and 53-time nominee has either dozens or hundreds of albums, depending on how you count them. Where does one possibly begin? Given that he doesn't really have specific, delineated eras, it's more helpful to cherry pick the most essential albums, decade by decade, while still noting relatively minor entries of interest.

Let's go places we've never been, and see things we may never see again — in this edition of Songbook.

Listen to GRAMMY.com’s Songbook: An Essential Guide To Willie Nelson playlist on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

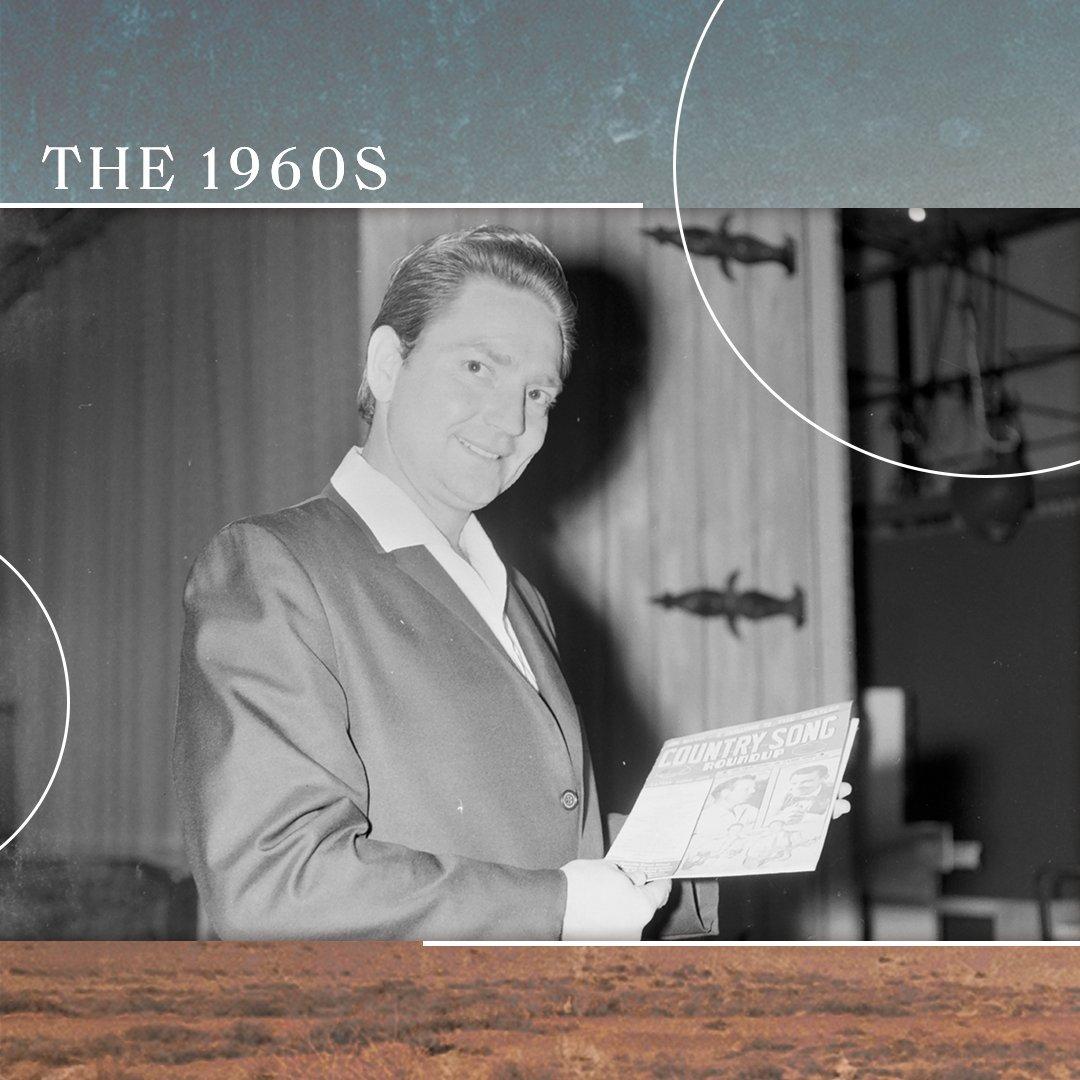

The 1960s

Willie Nelson backstage at "Arizona Hayride" TV show in November, 1964, in Phoenix, Arizona | Photo: Johnny Franklin/andmorebears/Getty Images

While Nelson made his first recordings in the mid-1950s, his discography began in earnest in 1962, with his debut album …And Then I Wrote.

…And Then I Wrote is absolutely worth hearing for its decadent production, introduction of Nelson's Django Reinhardt-inspired nylon-string picking, and key early compositions like "Funny How Time Slips Away" and "Crazy."

The baby-faced country crooner on the cover was in for the adventure of a lifetime. Listen to …And Then I Wrote, consider how Nelson's voice is pretty much the same 60 years on — albeit weathered by age and weed smoke — and you'll realize he essentially came out fully formed.

Do you dig the songs on …And Then I Wrote, but don’t like the semi-excessive reverb and instrumentation typical of Nashville back then? Head for 1965's Country Willie: His Own Songs for alternate versions of tracks like "Funny How Time Slips Away," "Mr. Record Man," and cuts from his second album, 1963's Here's Willie Nelson. But all in all, seek out 1973's The Best of Willie Nelson for a handy sampler platter from his first decade on record.

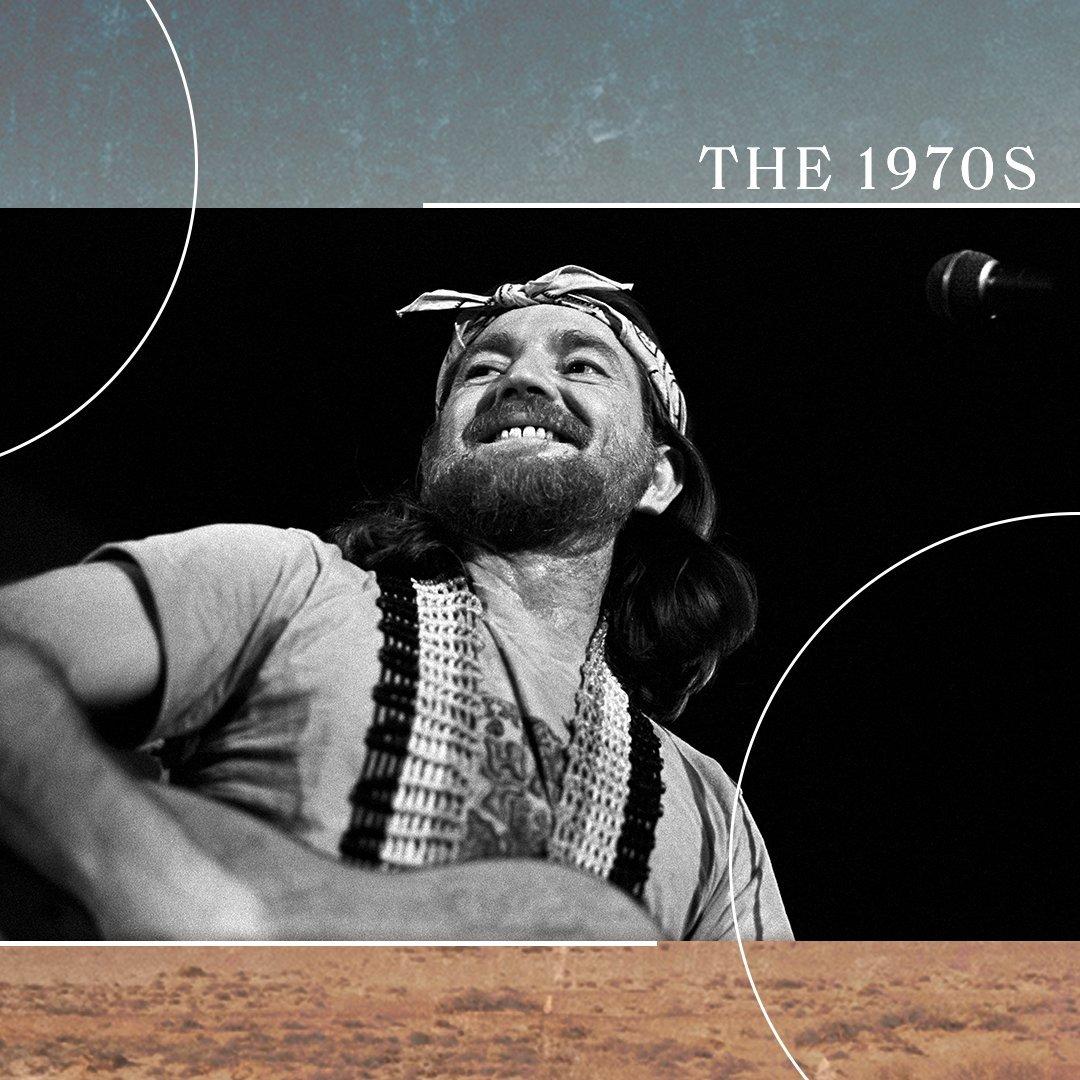

The 1970s

*Willie Nelson performs at the Great Southeast Music Hall on October 27, 1975 in Atlanta, Georgia | Photo: Tom Hill/Getty Images*

Forged and rebirthed by a ranch fire and divorce — not to mention professional bumps in the road — Nelson entered the 1970s with his first masterpiece: 1971's Yesterday's Wine, which contains classics like "Family Bible" and the title track.

Begin your trawling through Nelson's '70s with that record, then follow up with his 1973 breakthrough, Shotgun Willie, whose sound, attitude and songs helped forge the "outlaw country" subgenre. 1974's slightly less discussed Phases and Stages is a heady exploration of a marriage’s unraveling.

Then drop the needle on 1975's Red Headed Stranger, which further cemented Nelson's reputation as an outlaw-country mainstay and contained his immortal version of Fred Rose's "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain." (Talk about making a shopworn song your own!)

If you want a more raucous Nelson offering from this decade, seek out 1976's The Troublemaker, a rough-and-tumble collection of traditional songs.

1977's To Lefty From Willie, a tribute to country singer Lefty Frizzell, is Nelson's first album-length tip of the hat to another artist — he'd later do the same for Ray Price and George Gershwin. And 1978's Waylon and Willie is worth engaging with simply to hear two titans appear on the same record.

The other 1970s entry you must hear is Stardust, which veers away from Nelson's outlaw-country image in favor of jazzy renditions of traditional pop songs, like "Unchained Melody," "All of Me," "Moonlight in Vermont," and — most famously — "Georgia on My Mind."

Given there has never been a jazzier country artist than Nelson, Stardust is a pivot point in his discography by concept alone — one that shows the true depths of his artistry. Seek it out for that reason, and stay for the luminous music.

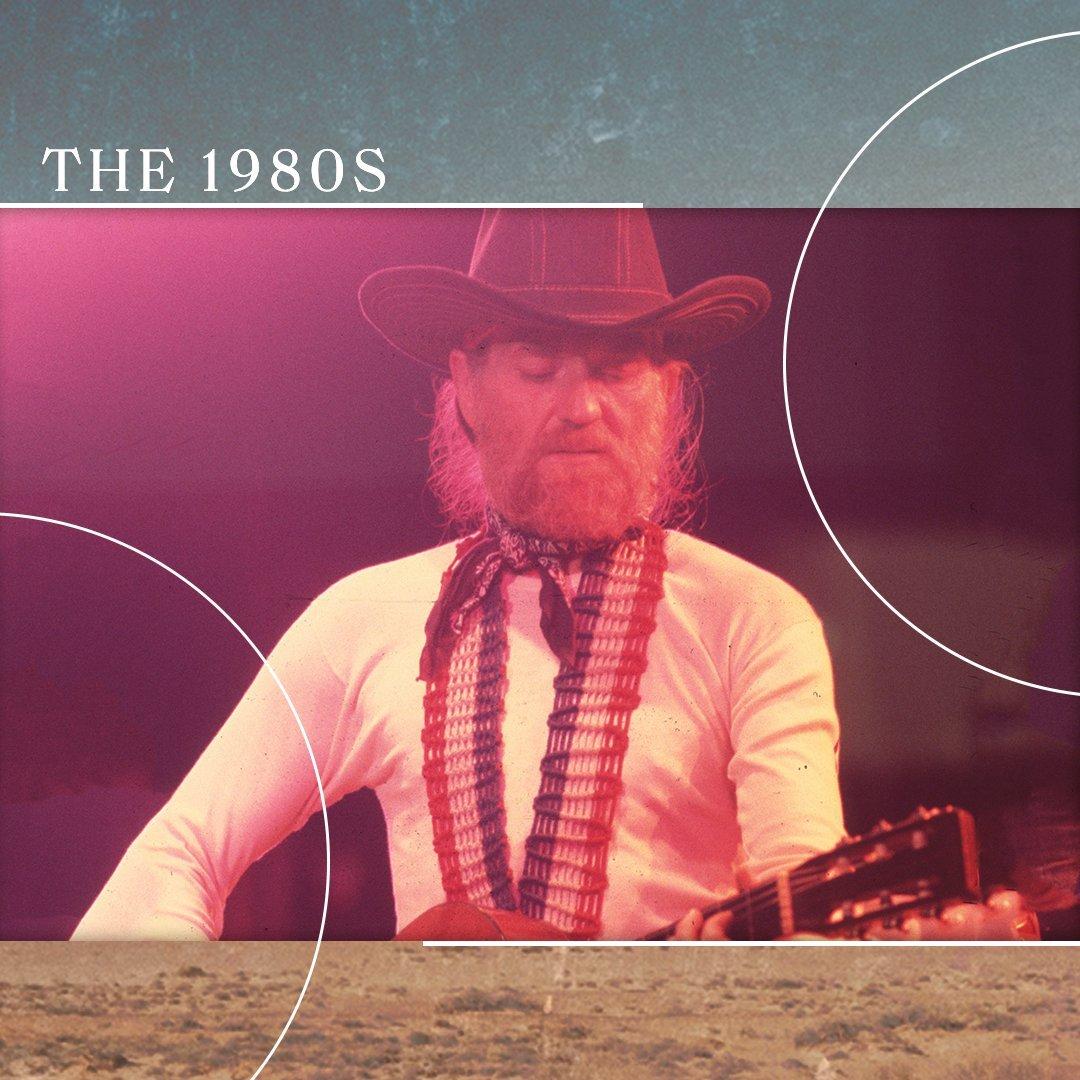

The 1980s

*Willie Nelson performs in 1980 | Photo: Chris Walter/WireImage*

Nelson kicked off the '80s with San Antonio Rose, a collaborative album with Ray Price that illustrated the profound bond between two foundational country figures. Also released in 1980, Family Bible was a duet album with Nelson's sister, pianist Bobbie, who passed away in 2022.

A successor of sorts to 1979's covers album Sings Kristofferson, Music From Songwriter was a duet between the pair. It also soundtracked the titular, well-recieved 1984 film, which starred both men.

The one drop-dead essential Nelson album of the decade, though, is 1983's Pancho & Lefty, his inspired team-up with fellow outlaw-countryman Merle Haggard.

The album featured unforgettable tunes like the Townes Van Zandt-penned title track — a narrative about a wanderer and Mexican "bandit boy" — as well as Haggard's "Reasons to Quit" and Jesse Ashlock's "Still Water Runs the Deepest." It also spawned multiple sequels, from 1987's Seashores of Old Mexico to 2015's Django & Jimmie.

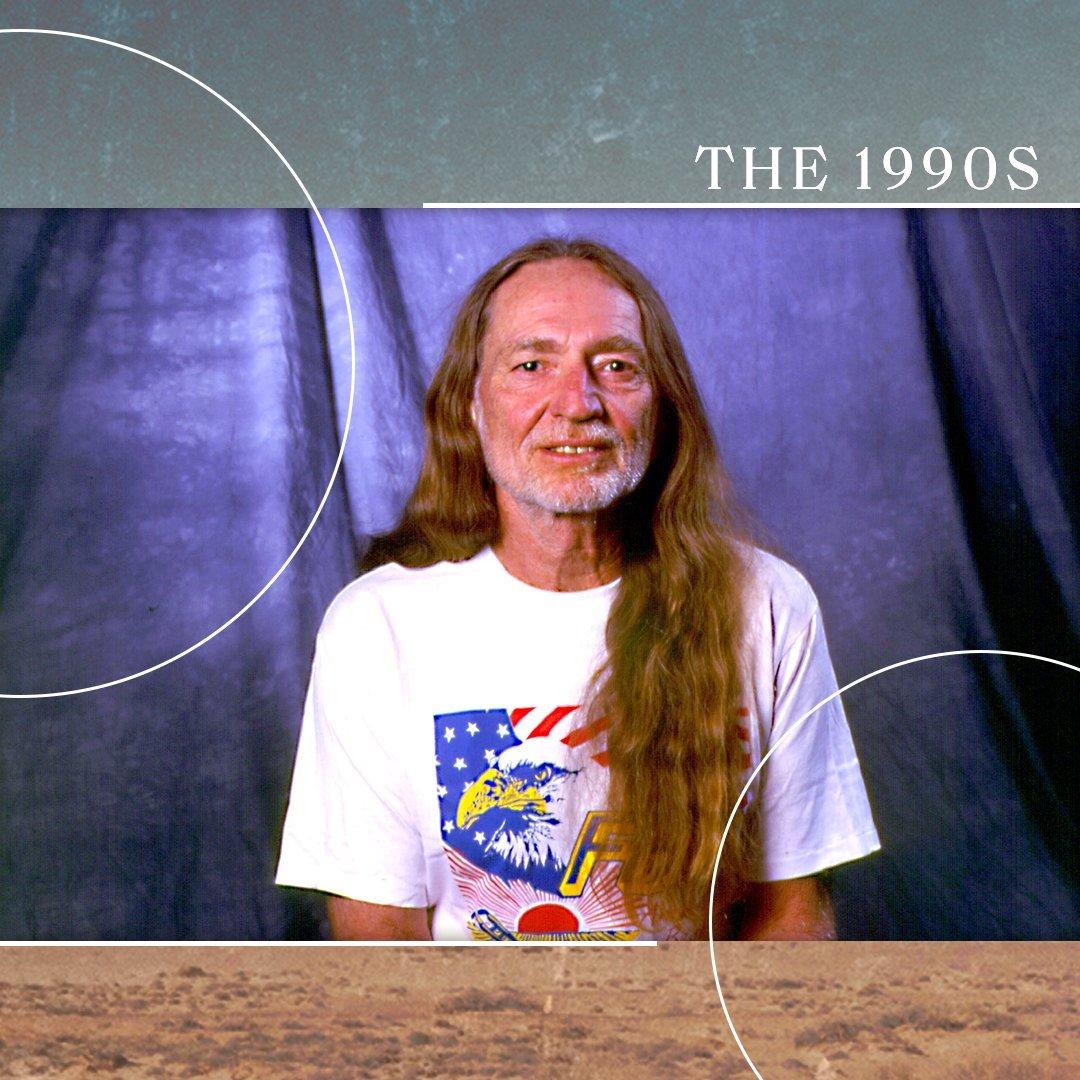

The 1990s

*Willie Nelson in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1994 | Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImage*

Nelson had a beyond rocky start to the decade: in 1990, the Internal Revenue Service seized most of his assets, claiming he owed a whopping $16 million. Long story short, he recorded Who'll Buy My Memories: The IRS Tapes to pay off part of the debt.

Although the album was well-received, it's safe to say it exists more of a reminder of this bizarre yarn than a standalone album worth cherishing. (Thank goodness Trigger survived the property seizure — Nelson's daughter, Lana, shipped it to him in Hawaii.)

A far more essential '90s Nelson listen is the haunting, stripped-down, Spanish-influenced Spirit, a quintessential "real heads only" album.

Featuring fiddler Johnny Gimble of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Spirit consists solely of crepuscular, yearning originals, like "Your Memory Won't Die in My Grave," "Too Sick to Pray" and "I Guess I've Come to Live Here in Your Eyes."

Also of interest from this decade in Nelson's discography: Teatro, which Daniel Lanois recorded in an old movie theater in Oxnard, California and features vocal contributions from the estimable Emmylou Harris.

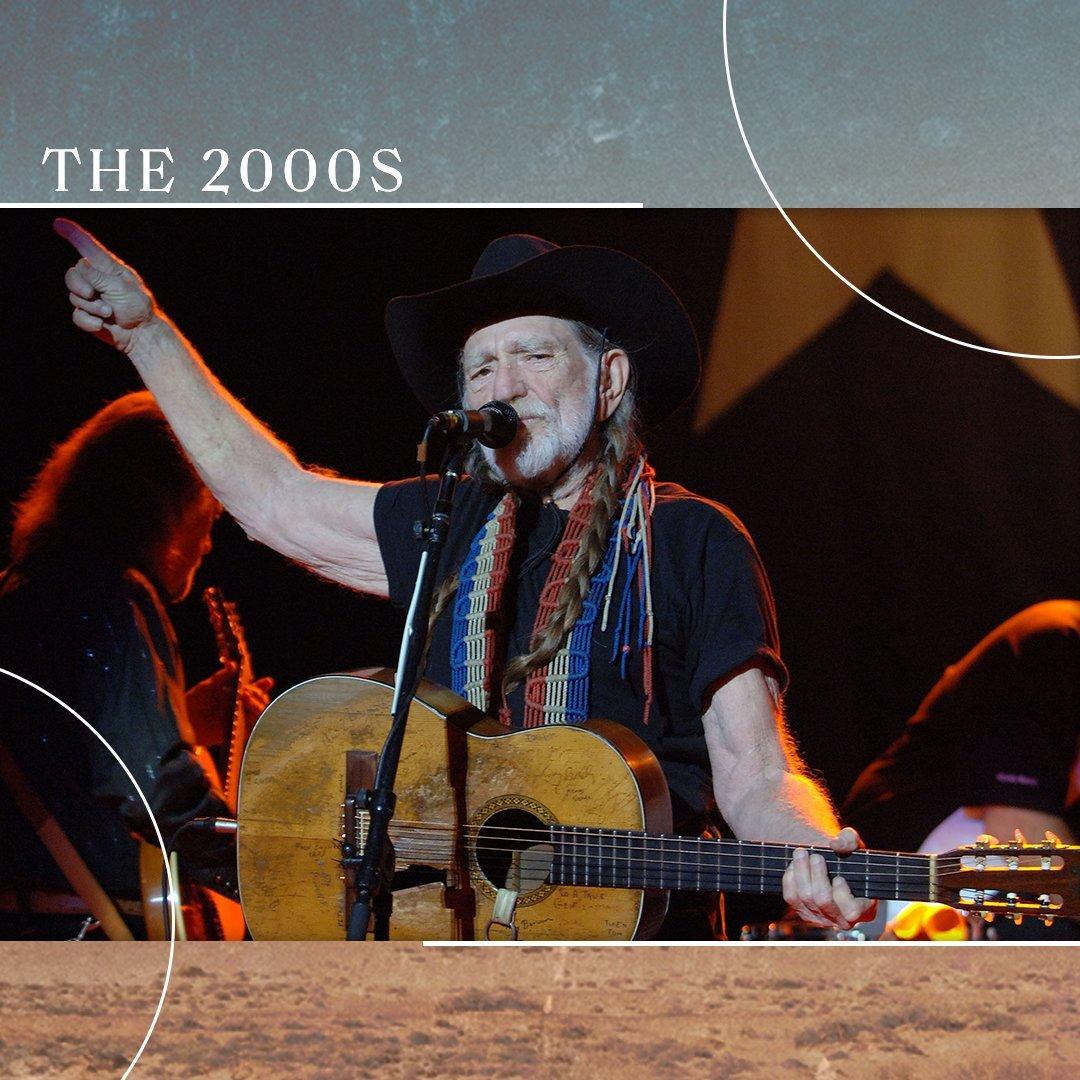

The 2000s

*Willie Nelson performs at The Mizner Park Ampitheatre in Boca Raton, Florida, in 2006 | Photo: Larry Marano/Getty Images*

In the young millennium, Nelson hit the road even harder than he did in the '90s, and collaborated with artists as divergent as Toby Keith ("Beer for My Horses"), Toots and the Maytals ("She is Still Moving to Me," "I'm a Worried Man") and Wynton Marsalis (2008's Two Men With the Blues).

The 2000s are also important in Nelson's development as they marked the start of his partnership with the two-time GRAMMY-winning producer Buddy Cannon. Their inaugural project was 2008's Moment of Forever, and Cannon produces or co-produces Nelson's yearly (or, in some cases, bi-yearly) albums to this day.

Other notable selections from this decade include 2006's Songbird, with Ryan Adams and the Cardinals, and 2007's western-swing excursion Last of the Breed, featuring the triple threat of Nelson, Haggard and Price.

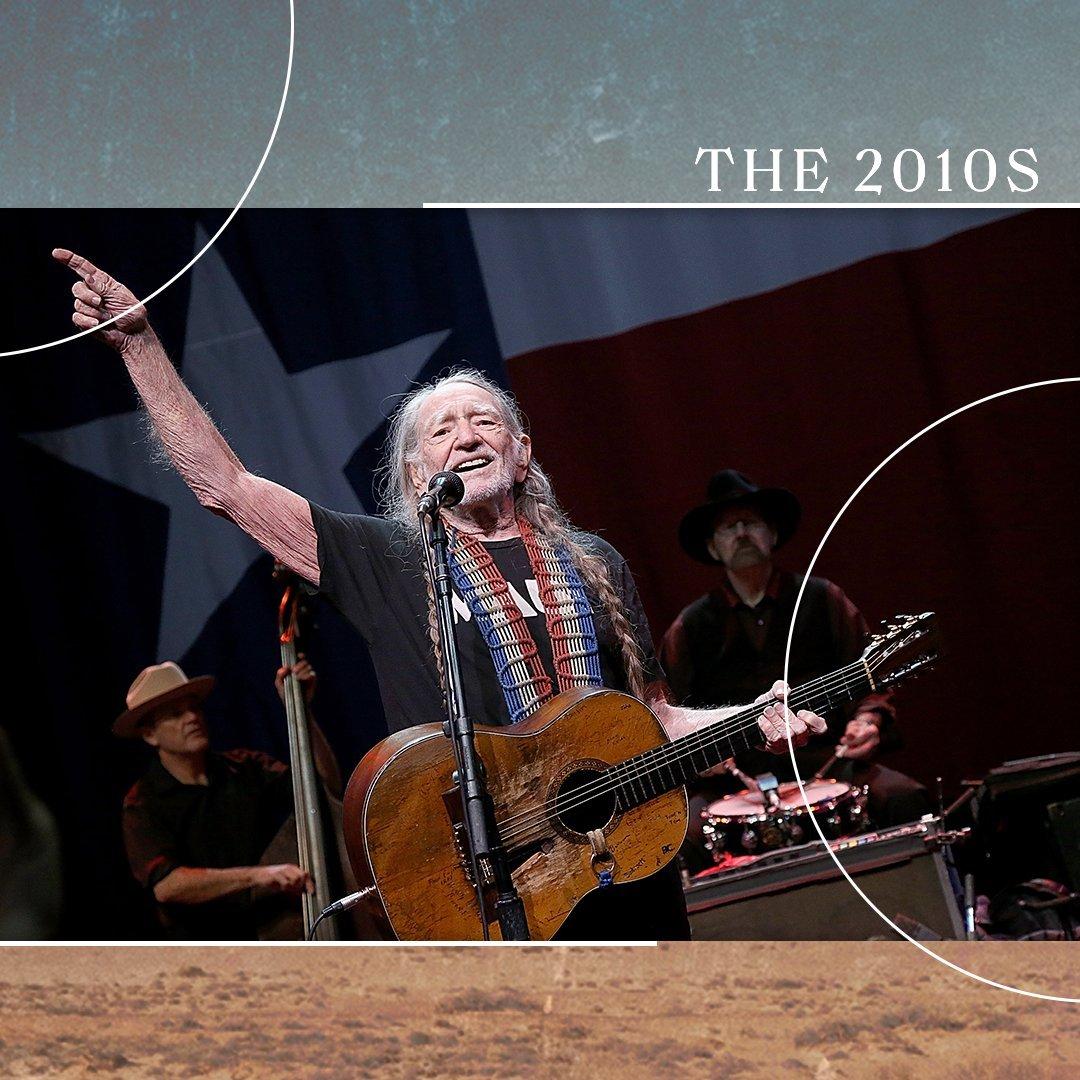

The 2010s

*Willie Nelson performs on New Year's Eve at ACL Live in 2014 in Austin, Texas | Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images*

Nelson was consistent and prolific throughout the 2010s. If you're a fan or just curious, you can conceivably drop into almost any album — from 2012's Heroes to 2014's Band of Brothers to 2018's Last Man Standing — and walk away smiling.

That said, a few stand out from the pack. Django and Jimmie, which marks Nelson and Haggard's sixth and final collaborative album, is by turns touching ("Somewhere Between") and uproarious (the irresistible stoner boogie "It's All Going to Pot").

What's more, Django and Jimmie is a glorious penultimate dispatch from the very missed Haggard, who died in 2016. Nelson touchingly paid tribute to his fallen friend on "He Won't Ever Be Gone," from 2017's excellent God's Problem Child.

Finish off your exploration of 2010s Nelson with 2018's My Way, a tribute to Frank Sinatra, and 2020's spare-yet-satisfying Ride Me Back Home.

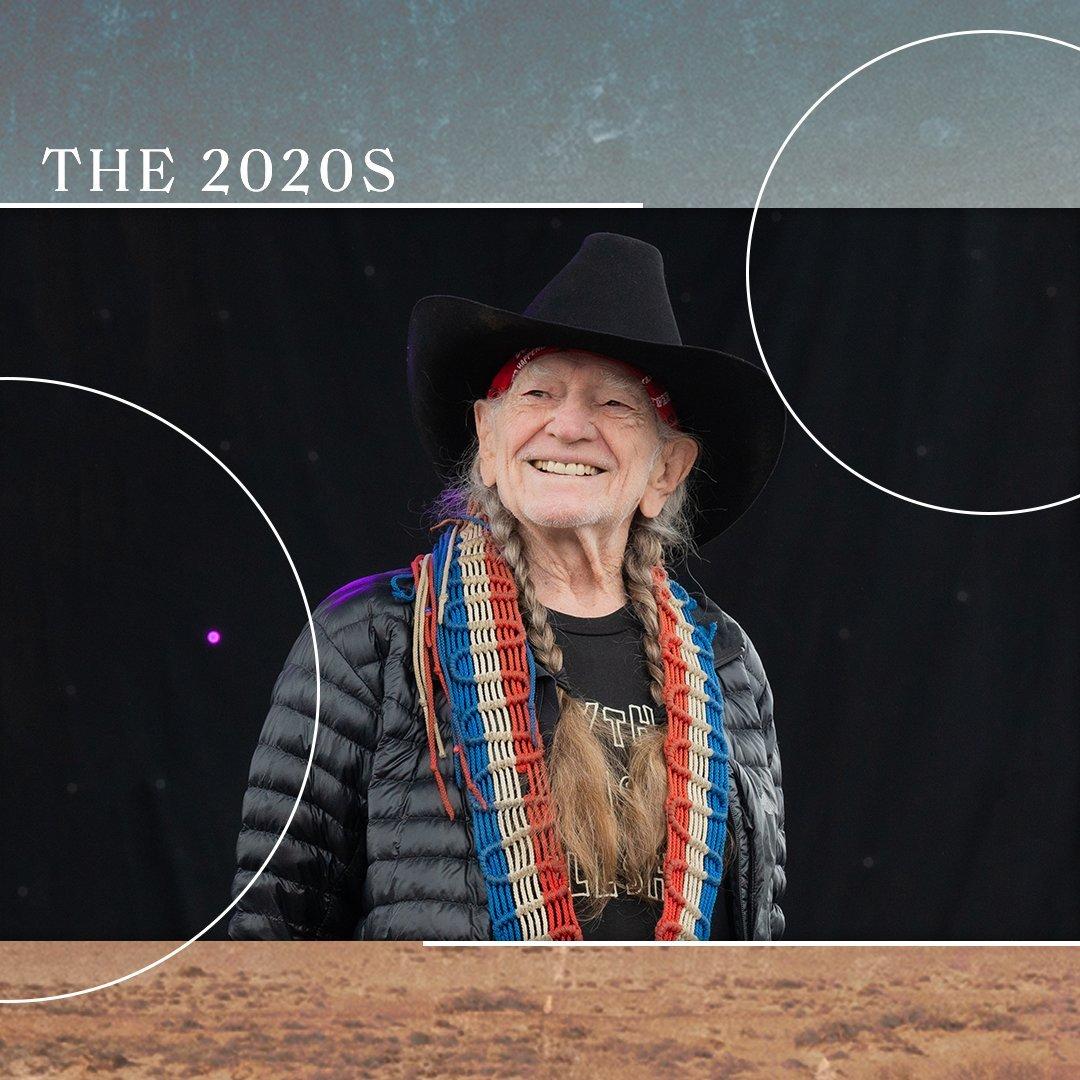

The 2020s

*Willie Nelson performs at the Luck Reunion in 2022 in Luck, Texas | Photo: Jim Bennett/WireImage*

By all available evidence, Nelson is firing on all cylinders in the 2020s. He entered the new decade with 2020's tender First Rose of Spring. Nelson followed that up almost immediately with 2021's That's Life, another excellent tribute to Sinatra.

That year's The Willie Nelson Family reflected his eternal bond with his biological and musical family — Nelsons Amy, Bobbie, Lukas, Micah and Paula. And on April 29, Nelson gave us A Beautiful Time, a gorgeous collection of originals and covers, with an especially touching title track written by Shawn Camp.

"If I ever get home/ I'll still love the road/ Still love the way that it winds," Nelson sings therein. "Now when the last song's been played/ I'll look back and say/ I sure had a beautiful time."

The song carries a tinge of finality, and on the cover, Nelson strolls into the sunset. Does it signal that Nelson is finally winding down? It'd be presumptuous to say so, even though he's numberless albums deep and will turn 90 in 2023.

Despite recent health issues, Nelson is magically, gratefully still on the road. He sings as well, or better, than ever. And his guitar playing alone remains an idiosyncratic force — to say nothing of his still-intact songwriting and interpreting talents.

For all his travails and triumphs, Nelson has remained creatively vital and deeply himself throughout his astonishing career and into his seventh active decade — partly because of his family’s support, partly for staying uncompromising, but also because he never let the old man in.

Photo: ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images

list

10 Songs You Didn't Know Dolly Parton Wrote: Hits By Whitney Houston, Kenny Rogers & More

Country icon Dolly Parton has had plenty of hits with her own name on it, but she’s also behind several songs by some of her fellow legends in country music and beyond

Dolly Parton estimates that she has written close to 3,000 songs throughout her illustrious seven-decade career. While 450 of those songs have been recorded, Parton hasn't always been the artist to sing them: Merle Haggard, Hank Williams Jr. and Kenny Rogers have famously recorded and released tracks written by the 10-time GRAMMY winner.

"I love to write songs for men," Parton says in her 2020 book, Dolly Parton, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics. "And it's a good thing I do because back then, there weren't that many women in the country-music business to write songs for. Especially ones who weren't writing their own songs, like Loretta Lynn was. I didn't have a lot of space to write songs for women so I purposefully tried to write songs that men could record. Or songs that could go either way."

That's not to say women haven't been a part of Parton's canon. She penned songs that have been recorded by Emmylou Harris and Skeeter Davis, and even gave Whitney Houston one of the biggest songs of her career.

Parton's songs have taken on new life thanks to artists across countless genres. In celebration of the Country Music Hall of Famer's 76th birthday on Jan. 19, GRAMMY.com takes a look back at 10 songs you may not have known Dolly Parton wrote.

"Put It Off Until Tomorrow," Bill Phillips

Before Parton became a household name for her own music, she was a songwriter for other artists. In January 1966, Bill Phillips released one of the songs she penned, "Put It Off Until Tomorrow," on which she provided backing vocals. The song peaked at No. 6 on Billboard's Hot Country Songs chart three months later, and the track's success helped garner Parton a recording contract with Monument Records. (Phillips also recorded Parton's "The Company You Keep," which became another top 10 hit later that year.)

"Fuel to the Flame," Skeeter Davis

Parton's career may not have taken off without her uncle Bill Owens, who recognized his niece's talent from a young age. In her early years in Nashville, Parton would frequently write with Owens and one of their earliest cuts together was when Skeeter Davis recorded and released "Fuel to the Flame" as a single in 1967. A beautiful ballad of a burgeoning love, "Fuel to the Flame" gave Davis her first major hit in two years, helping the star prolong her career while simultaneously helping launch Dolly's.

"Kentucky Gambler," Merle Haggard

A year before he wrote "Always Wanting You" for Dolly, Haggard recorded "Kentucky Gambler" in September 1974 at Nashville's Columbia Studios while Parton provided harmony. A song about a miner who left behind his wife and kids, "Kentucky Gambler" is a classic Dolly Parton story song providing a lesson on greed.

Released as a single with the Strangers later that year, Haggard's version of "Kentucky Gambler" reached No. 1 on Jan. 18, 1975. Parton recorded her own version of the song in 1973 and included it on her 1975 album The Bargain Store, but Haggard's rendition is most recognized today.

"There'll Always Be Music," Tina Turner

Two years after Tina Turner and then-husband Ike Turner got the world dancing with their iconic hit "Proud Mary," Tina kicked off her solo career by dabbling in country music. Her 10-track debut solo studio album, Tina Turns the Country On!, had an A-list roster of songwriters including Kris Kristofferson, Bob Dylan, James Taylor, Hank Snow and Parton, who penned "There'll Always Be Music."

The piano ballad showcased Turner's soulful vocals and was an introduction to Turner apart from the Ike & Tina Turner Revue. While the album didn't chart, it did earn Turner a GRAMMY nomination for Best R&B Vocal Performance, Female.

"I'm In No Condition," Hank Williams Jr.

Like many of Parton's songs that were recorded by someone else, the singer still included her own version of "I'm In No Condition" on her 1967 album Hello, I'm Dolly. But after listening to Hank Williams Jr.'s rendition, it's hard to believe it was written for anyone but him.

An honest portrayal of the struggle in the aftermath of a breakup, the song laments a love he didn't want to end — underlined by the song's titular chorus line, "I'm in no condition to try to love again." Though it wasn't one of Williams Jr.'s most successful singles, it certainly encapsulated the vulnerability the bellowing star brought to the genre.

"Circle of Love," Jennifer Nettles

Jennifer Nettles played the role of Parton's mother, Avie Lee Parton, in the 2016 television movie "Dolly Parton's Christmas of Many Colors: Circle of Love" based on a true story from Parton's childhood. In classic Dolly fashion, she penned the film's heartfelt title track by herself.

Moved by the waltzing song's biblical message, Nettles also included her version on her solo To Celebrate Christmas holiday album released that year. Parton shared her own recording on her 2020 holiday album, A Holly Dolly Christmas, which is nominated for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album this year, and teamed up with Nettles to duet the song on "The Voice" that December.

"The Stranger," Kenny Rogers

One month before Parton and her longtime collaborator Kenny Rogers released their revered Once Upon a Christmas holiday album, Rogers unveiled his What About Me? album in October 1984. Though that project didn't include vocals from his singing partner, Rogers still had a touch of Dolly on the record: the powerful story song "The Stranger," written by Parton.

It's a tale of a boy wondering why his father deserted him before he was born only to meet him a decade after his mother's death. "The Stranger" is a descriptive and heart-wrenching tune that pulls the listener right into the song. "It was me and mamma that you left behind," Rogers croons at the song's close. "You're just a stranger."

"Waltz Me to Heaven," Waylon Jennings

While Parton reportedly wrote "Waltz Me to Heaven" for Waylon Jennings, the song first appeared on the 1984 film soundtrack for "Rhinestone," starring Parton and Sylvester Stallone. Her youngest brother, Floyd Parton, sang on the original track.

Later that year, Jennings included "Waltz Me to Heaven" on Waylon's Greatest Hits, Vol. 2. The stirring waltz highlights Jennings' memorable baritone alongside sweeping pedal steel and delicate fiddle accompaniment. Jennings' "Waltz Me to Heaven" made the soundtrack song a hit, reaching No. 10 on Billboard's Hot Country Songs chart.

"To Daddy," Emmylou Harris

A song written from the perspective of a teenager watching an unhappy relationship between her parents transpire, "To Daddy" sees the mother leaving her unaffectionate husband. The poignant tale clearly meant a lot to Harris and Parton, as Emmylou released it as a single from her 1977 album, Quarter Moon in Cent Town, and Dolly included it in her 1995 compilation, The Essential Dolly Parton, Vol. 1.

Harris' version also resonated with fans: It scored her a No. 3 hit on Billboard's Hot Country Songs chart in 1978, and it was the only song featured on the 2003 tribute album Just Because I'm a Woman: Songs of Dolly Parton that wasn't recorded specifically for the project.

"I Will Always Love You," Whitney Houston

Long before Whitney Houston broke countless records with her rendition of "I Will Always Love You," Parton wrote and released the song as a letter to Porter Wagoner. After telling Wagoner she wanted to leave The Porter Wagoner Show countless times and Wagoner ignoring those wishes, Parton decided to do what she does best: write a song.

"I wrote the song, took it back in the next day, and I said, 'Porter, sit down. I've got something I have to sing to you,'" Parton recalled in Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns' Country Music book and documentary. "So, I sang it, and he was sitting at his desk, and he was crying. He said, 'That's the best thing you ever wrote. Okay, you can go, but only if I can produce that record.'"

While Parton's recording landed at No. 1 on two different occasions (upon its release in 1974 and again in 1982, when a new version was recorded and released for the film The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas), it was Houston's spellbinding 1992 version from The Bodyguard that took the world by storm.

Spending 14 consecutive weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, Houston's "I Will Always Love You" became the best-selling physical single by a woman, with 20 million copies sold to date. Houston's version also took home Record Of The Year and Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female at the 1994 GRAMMYs — creating an everlasting legacy for Whitney and Dolly alike.

Travis Tritt

David Abbott

news

Travis Tritt On His 'Gratifying' Legacy and Why He Made His First Album in 14 Years

Country veteran Travis Tritt recounts the meaningful conversations and collaborations that led to his 11th studio album, 'Set in Stone'

Travis Tritt was faced with an almost unfamiliar feeling when the COVID pandemic put the live market on pause in March 2020. After dedicating more than a decade to touring, Tritt—a self-proclaimed "road dog"—went back into the studio for the first time in 13 years.

The timing was a convenient coincidence, as Tritt's manager, Mike "Cheez" Brown, had floated the idea in 2019. "One of the first things [Mike] told me when we started working together was, 'I still think you've got a lot of music left in you,'" Tritt recalls to GRAMMY.com. "The more we started talking about an album, the more I started thinking that was a really good idea. But I had been out of the studio for so long, I still had a little bit of concern about it."

Luckily for Tritt, Brown had just finished working with GRAMMY-winning producer Dave Cobb (Brandi Carlile, Chris Stapleton) on the Dirty Heads' 2019 LP Super Moon. Cobb not only eased Tritt's worries but opened up an entirely new realm of co-writers for the superstar—many of whom reminded Tritt of the legacy he's built. The result is Set in Stone, which dropped May 7 via Big Noise. The album celebrates Tritt's classic outlaw country sound as well as his influence on the genre that is, well, set in stone.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Travis Tritt about Set in Stone and how it served as a reminder of his lasting impact.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//qZDrI3KlpFE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

It's been nearly 14 years since you last released an album. With all that has changed about music in that time, were you nervous about getting back into the studio?

Prior to sitting down and talking with Dave about his process, I did have a good bit of anxiety and nervousness about it. He records with a live band—no digital sampling going on—and tries to record as many live vocals as possible during that same period. That's the way I've done it since I first started recording back in the '80s. I don't think this album would be what it is if it hadn't been for that opportunity to work together.

Did he bring anything different to the table, since your recording processes were similar?

He set me up with some of his favorite writers, like Brent Cobb, Adam Hood, Wyatt Durette, Channing Wilson, Ashley Monroe, Dillon Carmichael. Pretty much every writer that I worked with told me how much my music had influenced them when they were young. That was humbling and gratifying. It was something that I really didn't expect.

In the first writing session [with Brent], he said, "Man, I was thinking about the kind of influence and impact that you had on so many people, including me. You don't have anything left to prove to anybody. Your legacy is pretty much set in stone." He had the first verse of "Set in Stone" and a couple of lines for the chorus already in his head. I heard it and immediately fell in love with the idea.

That's a pretty big statement! Did any other conversations result in songs for the album?

The first track, "Stand Your Ground," came from getting to know [co-writers] Channing Wilson and Wyatt Durrette. They were asking me about how I got started in Nashville, and I told them about the first time I met Waylon Jennings.

It was at a time when I was getting a good bit of criticism for doing things my own way, and a little bit different than the average country artist at the time. Waylon told me, "Listen, I've been hearing all the things that they've been saying about you. Just remember that [it's] exactly the same things they said about me, and about Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, Jr., and David Allan Coe.

The only people you need to be concerned about are your fans, your audience. Those are the only people that matter." I told that story to Channing and Wyatt, and they immediately said, "We've got to write that."

Did any of your co-writers tell you that your less-traditional approach inspired them?

Almost all of them. A lot of those younger artists gave me a lot of credit for being able to stand up to record labels and say, "I think I know my audience better than any of you people, and I'm going to just stick with what I know." Some of them actually said, "You had a lot of balls to be able to do that." [Laughs.]

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//no49WL0OVig' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Had you thought about your legacy before making this album?

I'll be honest with you—prior to meeting all these writers, I never really thought about what my potential legacy would be, and how much my influence would be affecting so many of these young people.

To realize that you've had—not only a successful career—but a positive influence on other people that want to follow their dream the same way that you did is something that I am amazed by. It's something that I am humbled by, and it's something that, quite frankly, I take a lot of pride in.

So many of these younger artists, songwriters, producers and people involved in the industry look up to me the same way that I looked up to some of my heroes, like Johnny Cash and George Jones. To be thought of in that way is an extreme honor. It's kind of like gravy on top of everything else.

I thought it was awesome that you ended the album with an homage to your home state with "Way Down in Georgia." How have your Georgia roots played a part in your career?

Georgia has influenced me tremendously. Very early on when I was first starting to have success, I had a ton of people that said, "You've got to move to Nashville." I always resisted that. Not because I had anything against Nashville, but because no place felt like home to me the way that Georgia has. It keeps me grounded, it keeps me centered.

The other advantage is that I can still drive by places I went as a young man and have a specific memory come back, and end up writing a song about that. So many of the songs that I've written over the years were triggered by a memory that came from being close to where I grew up. Including songs for this album, like "They Don't Make 'Em Like That No More." I drove by a park where I took a beautiful girl on a date, and all of those memories came back and [inspired the lyric] "She was the prettiest thing this ol' boy had ever seen."

You've been able to play some shows recently. Has the energy felt different, considering your concert has likely been the first post-pandemic live show for many?

Definitely. I've noticed a palatable hunger. It's like a caged animal, you know? You keep an animal in a cage for a long period of time and when they get out, the first thing they're gonna do is sprint and go crazy, just to be enjoying a little bit of that freedom again. I think that's what we're seeing every single night. The excitement is overwhelming.

The sentiment of your hit "It's a Great Day to Be Alive" is all about enjoying life. Does it feel like fans are embracing that even more so now, considering the difficult year we've all endured?

I was doing a show in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and I noticed when I did that particular song, there were a few people running up and down the aisles high-fiving people. That's always been a song about celebration and the celebration of life, but I think you're exactly right. It's even more so now because people are not taking opportunities to enjoy their life for granted any longer.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//YDBTlv1z0dA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Now that you've been back in the studio and writing again, it sounds like there probably won't be another 14-year gap before your next album?

No, I don't think so. Now that I've had opportunities to work with these younger songwriters, and some of these producers that are current and relevant today, I think you can anticipate that I will be not having these long hiatuses in the future. I'm definitely going to be writing and recording more, and I'm going to try to bring new music to the table as often as I can. [Dave Cobb], my manager, and these young songwriters all contributed to helping light a fire underneath me.

Is there anything left on your career bucket list?

I have worked with just about everybody that I've ever wanted to work with. I really don't see a whole lot of things that I would look at and say, "That's something I've never done or experienced."

All I ever wanted to do was just make music that moved me. To be able to look back on selling over 30 million albums and having the opportunity to perform in front of millions of people over the years—and still be able to honestly say that I love it just as much now as I ever did—it's an honor, a privilege, and a pleasure.

I've had the blessing of so many great experiences in my life. I just want to keep on doing it. There's an old expression, "Dance with the one that brought you." I just want to keep dancing.