Photo: Erika Goldring/WireImage.com

news

The Making Of Wayne Shorter's "Orbits"

GRAMMY winner details his adventure in rerecording his Best Improvised Jazz Solo-winning "Orbits"

(The Making Of GRAMMY-Winning Recordings … series presents firsthand accounts of the creative process behind some of music's biggest recordings. The series' current installments present in-depth insight and details about recordings that won 56th GRAMMY Awards.)

(As told to Don Heckman)

"Orbits" goes way back. As far as the '60s. I wrote the original version, called it "Orbits," and first recorded it in 1967 with Miles Davis [for his album] Miles Smiles. After that, we recorded it with a larger ensemble with woodwinds in 2003 on an album called Alegria, which also won a GRAMMY.

The whole album had a spontaneous [feel]. In fact, every step was a surprise because the "Orbits" from [2013's] Without A Net that won the GRAMMY was done without any rehearsal. And I think that's where the world is at today. We have to learn how to negotiate the unexpected. Everyone has to learn how to break free [from] any kind of handcuffs [or] images of grandeur. Both music and life should be an adventure, not a job.

We were working at Yoshi's in San Francisco before "Orbits" came out on Without A Net and Vonetta McGee, the actress, was there. I'd known her since she was 16. She came backstage and said, "You know, these guys are playing without a net." And later on, when we were performing in North Carolina for a fundraiser, we were having dinner at a restaurant, with [a professor]. And I mentioned the phrase again, "without a net." And he said "What does that mean?" And I said, "It means that it isn't important what we play, it's how we play it."

But I was really surprised when "Orbits" won the GRAMMY. When something like this happens, you don't want to go back and second guess yourself. Like starting to think that you should have done this, or you should have done that. Which [reminds] me that one of the first things we were asked when I was in Japan with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers back in the '60s was, "What is originality? What is the creative process?" And I said that I think the creative process is the courage to take leaps into the unknown. To take chances. Deal with the unfamiliar and the unexpected. Risk removing yourself from [your] comfort zone.

And it takes a lot of work along the way to do that. They used to say, "Hey, Jackson Pollock is just throwing stuff at the canvas. That's not creative." And my response was, "Hey, how he was applying it to the canvas [and] how he was doing it is what matters." And each how he did was different. Which [reminds] me of what Miles used to say: "If you don't have anything to say when you play, don't play."

The way I look at it — at "Orbits" or anything else I've done — is that the creative process always has an element of surprise. And even if the surprise is ignored, or the surprise is not recognized by the recipient, it's there anyway. It's like when it's dark outside and raining, but the sun is still there, still shining.

(At the 56th GRAMMY Awards, Wayne Shorter won for Best Improvised Jazz Solo for "Orbits." The song, which was previously recorded and released on Miles Davis' 1967 album Miles Smiles, is featured on Shorter's 2013 album Without A Net, which peaked at No. 2 on Billboard's Jazz Albums chart. Shorter has won nine prior GRAMMY Awards, including those as part of the Wayne Shorter Quartet and Weather Report.)

(Don Heckman has been writing about jazz and other music for five decades in The New York Times,Los Angeles Times, Jazz Times, Down Beat, Metronome, High Fidelity, and his personal blog, the International Review of Music.)

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

list

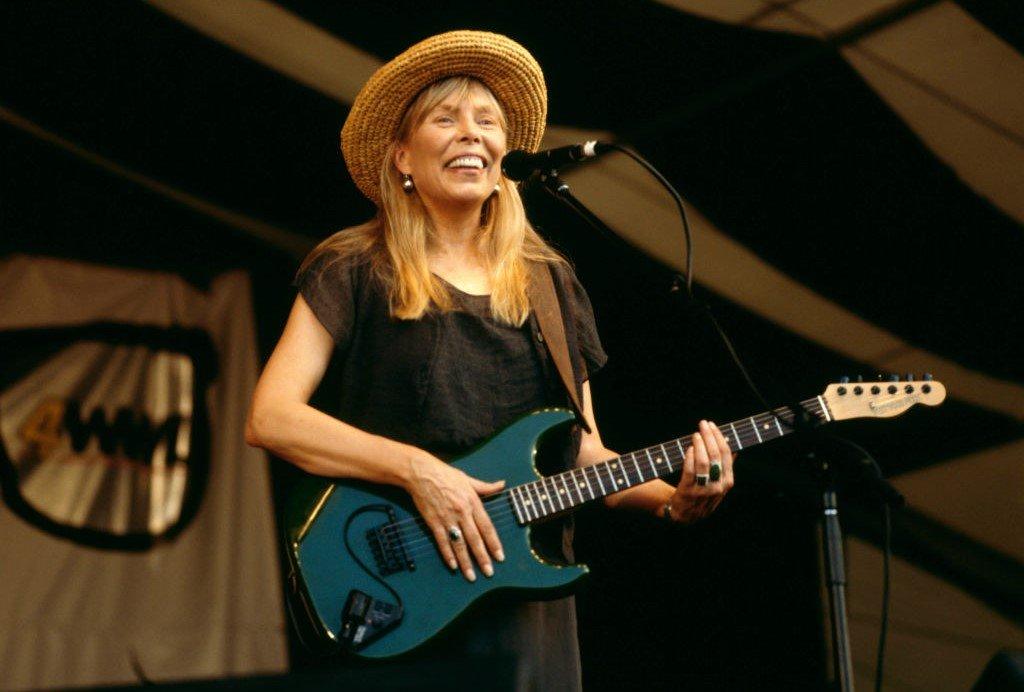

10 Lesser-Known Joni Mitchell Songs You Need To Hear

In celebration of Joni Mitchell's 80th birthday, here are 10 essential deep cuts from the nine-time GRAMMY winner and MusiCares Person Of The Year.

Having rebounded from a 2015 aneurysm, the nine-time GRAMMY winner and 17-time nominee has made a thrilling and inspiring return to the stage. Many of us have seen the images of Mitchell, enthroned in a mockup of her living room, exuding a regal air, clutching a wolf’s-head cane.

Again, this adulation is apt. But adulation can have a flattening effect, especially for those new to this colossal artist. At the MusiCares Person Of The Year event honoring Mitchell ahead of the 2022 GRAMMYs, concert curators Jon Batiste — and Mitchell ambassador Brandi Carlile — illustrated the breadth of her Miles Davis-esque trajectory, of innovation after innovation.

At the three-hour, star-studded bash, the audience got "The Circle Game" and "Big Yellow Taxi" and the other crowd pleasers. But there were also cuts from Hejira and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Night Ride Home, and other dark horses. There were selections that even eluded this Mitchell fan’s knowledge, like "Urge for Going." Batiste and Carlile did their homework.

But what of the general listening public — do they grasp Mitchell’s multitudes like they might her male peers, like Bob Dylan? Is her album-by-album evolution to be poured over with care and nuance, or is she Blue to you?

Of course, everyone’s entitled to commune with the greats at their own pace. However, if you’re out to plumb Mitchell’s depths beyond a superficial level, her 80th birthday — which falls on Nov. 8 — is the perfect time to get to know this still-underrated singer/songwriter legend better. Here are 10 deeper Mitchell cuts to start that journey, into this woman of heart and mind.

"The Gallery" (Clouds, 1969)

Mitchell blew everyone’s minds when David Crosby discovered her in a small club in South Florida. Her 1968 debut, Song to a Seagull, contains key songs from that initial flashpoint, like "Michael from Mountains" and "The Dawntreader."

Mitchell’s artistic vision truly coalesced on her second album, Clouds. Although the production is a little wan and bare-boned, Clouds contains a handful of all-time classics, including "Chelsea Morning," "The Fiddle and the Drum" and the epochal "Both Sides, Now."

That said, "The Gallery," which kicks off side two, belongs at the top of the heap. There remain rumblings that it’s about Leonard Cohen. But whatever the case, Mitchell’s excoriating burst of a pretentious cad’s bubble ("And now you're flying back this way/ Like some lost homing pigeon/ They've monitored your brain, you say/ And changed you with religion") remains incisive, with a gorgeous melody to boot.

(And, it must be said: "That Song About the Midway," also found on Clouds, is a kiss-off to Croz, whom she enjoyed a fleeting fling with and a must-hear.)

"Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire" (For the Roses, 1972)

If you think you’ve got a grasp of Mitchell’s early talents, a new archival release proves they were more prodigious than you could imagine.

Joni Mitchell Archives, Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975) kicks off with a solo version of "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire." And as great as the studio version is, from 1972’s For the Roses, this version, from a session with Crosby and Graham Nash, arguably eats its lunch.

While Neil Young’s "The Needle and the Damage Done" has proved to be the epochal junkie-warning song of the 1970s, Mitchell’s song about the same subject easily goes toe to toe with it.

Images like "Pawn shops crisscrossed and padlocked/ Corridors spit on prayers and pleas" and "Red water in the bathroom sink/ Fever and the scum brown bowl" are quietly harrowing. Via Mitchell’s acoustic guitar, they’re underpinned by downcast, harmonically teeming blues.

"Sweet Bird" (The Hissing of Summer Lawns, 1975)

The Hissing of Summer Lawns is an unquestionable masterstroke of Mitchell’s fusion era.

Highlights are genuinely everywhere within Lawns — from the swinging and swaying "In France They Kiss on Main Street," to the Dr. Dre-predicting "The Jungle Line," to the title track, a hallucinatory lament for a trophy wife.

But amid these manifold high points, don’t miss "Sweet Bird," the penultimate track on The Hissing of Summer Lawns, tucked between "Harry’s House/Centerpiece" and "Shadows and Light."

"Give me some time/ I feel like I'm losing mine/ Out here on this horizon line," Mitchell sings through her dusky soprano, as the ECM-like atmosphere seems to whirl heavenward. "With the earth spinning/ And the sky forever rushing/ No one knows/ They can never get that close/ Guesses at most."

"A Strange Boy" (Hejira, 1976)

Much like The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira — retroactively, and rightly, canonized as one of Mitchell’s very best albums — is nearly flawless from front to back.

The highs are so high — "Amelia," "Hejira," "Refuge of the Roads" — that almost-as-good tracks might slip through the cracks. "A Strange Boy," about an airline steward with Peter Pan syndrome she briefly linked with.

"He was psychologically astute and severely adolescent at the same time," Mitchell said later. "There was something seductive and charming about his childlike qualities, but I never harbored any illusions about him being my man. He was just a big kid in the end."

As "A Strange Boil" smolders and begins to catch flame, Mitchell delivers the clincher line: "I gave him clothes and jewelry/ I gave him my warm body/ I gave him power over me."

"Otis and Marlena" (Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, 1977)

One of Mitchell’s most challenging and thorny albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is one of Mitchell’s least accessible offerings from her most expressionist era. (Mitchell in blackface on the cover, as a character named Art Nouveau, doesn’t exactly grease the wheels — to put it mildly.)

But across the sprawling and head-scratching tracklisting — which includes a seven-minute percussion interlude, in "The Tenth World" — are certain tunes that belong in the Mitchell time capsule.

One is "Otis and Marlena," one of the funniest and most evocative moments on an album full of strange wonders. Mitchell paints a picture of a cheap vacation scene, rife with "rented girls" and "the grand parades of cellulite" against a "neon-mercury vapor-stained Miami sky."

And the kicker of a chorus juxtaposes this dowdy Floridan outing with the realities up north, e.g. the 1977 Hanafi Siege: "They’ve come for fun and sun," MItchell sings, "while Muslims stick up Washington."

"A Chair in the Sky" (Mingus, 1979)

While Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is rather glowering and unwelcoming, Mingus is a cracked, cubist realm that’s fully inhabitable.

Initially conceived as a collaboration between Mitchell and four-time GRAMMY nominee Charles Mingus, it ended up being a eulogy: Mingus died before the album could be completed.

Despite its lopsided nature — it contains five spoken-word "raps," as well as a true oddity in the eerie, braying "The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" — Mingus remains rewarding almost 45 years later. And the Mingus-composed "A Chair in the Sky," with lyrics by Mitchell, is arguably its apogee.

Like the rest of Hejira, "A Chair in the Sky" features Jaco Pastorius and Wayne Shorter from Weather Report, as well as the one and only Herbie Hancock; this ethereal, ascendant track demonstrates the magic of when this phenomenal ensemble truly gels.

"Moon at the Window" (Wild Things Run Fast, 1982)

In Mitchell’s trajectory, Wild Things Run Fast represents the conclusion of her fusion phase, in favor of a more rock-driven sound — and, with it, the sunset of her second epoch.

Following Wild Things Run Fast would be 1985’s critically panned Dog Eat Dog and 1988’s even more assailed Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm. But for every arguable misstep, like the guitar-squealing "You Dream Flat Tires," there’s a baby that shouldn’t be thrown out with the bathwater.

One is "Chinese Cafe/Unchained Melody," another is "Ladies’ Man," and perhaps best of all is the luminous "Moon at the Window," where bassist/husband Larry Klein and Shorter wrap Mitchell’s sumptuous lyric, and melody, in spun gold.

"Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" (Night Ride Home, 1991)

At the dawn of the grunge era, Mitchell found her way back to her atmospheric best, with the gorgeously written, performed and produced Night Ride Home.

While its follow-up, Turbulent Indigo, won the GRAMMY for Best Pop Album (and is certainly worth savoring), Night Ride Home might have more to offer those who were enraptured by the majestic Hejira, and thirsted for a continuation of its aural universe.

The equally excellent "Come in From the Cold" is the one that has ended up on Mitchell setlists in the 2020s, but "Passion Play (When All the Slaves Are Free)" is even more transportive.

Despite the early 1900s sonics, "Passion Play" feels ageless and eternal, tapped into some Jungian collective unconscious as a wizened Mitchell posits, "Who’re you going to get to do your dirty work/ When all the slaves are free?"

"No Apologies" (Taming the Tiger, 1998)

If Night Ride Home sounds less played than conjured Taming the Tiger is like the steam that twists and disperses from its broiling, potent stew.

As much ambience pervaded Night Ride Home, Hejira and the like, Taming the Tiger is the only album in Mitchell’s estimable catalog to feel ambient.

Much of this is owed to Mitchell’s employment of the Roland VG-8 virtual guitar system, which allowed her to change her byzantine guitar tunings at the push of a button; the ensuing sound is a suggestion of a guitar, which enhances Taming the Tiger’s diaphanous and ephemeral feel.

"No Apologies" is something of a centerpiece, where Mitchell sings of war and a dilapidated homeland, sailing forth on a cloud of Greg Liestz’s sonorous lap steel.

"Bad Dreams" (Shine, 2007)

Mitchell has always cast a jaundiced eye at the music industry machine, so it’s no wonder she hasn’t released a new album in 16 years. (Although, as she revealed to Rolling Stone, she’s eyeing a small-ensemble album of standards with her old mates in the jazz scene.)

But if Shine ends up being her swan song, it’d be a fine farewell. "Bad Dreams" — written around a quote from Mitchell’s 3-year-old grandson: "Bad dreams are good / In the great plan" — is impossibly moving.

Therein, Mitchell considers an Edenic tableau as opposed to our modern world, where "these lesions once were lakes." Movingly, the song’s final lines accept reality for what it is ("Who will come to save the day? / Mighty Mouse? Superman?") rather than what she wishes it could be.

With that, Mitchell’s studio discography — as we know it today — reaches its conclusion. But although the artist is only fully getting her flowers today, we’ve only scratched the surface of the gifts she’s bestowed upon us.

Living Legends: Judy Collins On Cats, Joni Mitchell & Spellbound, Her First Album Of All-Original Material

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post via Getty Images

list

Remembering Wayne Shorter: 7 Gateway Tracks From The Jazz Titan's 1960s Run

The pioneering composer and tenor and soprano saxophonist passed away on March 2. His influence and legacy spans decades and permutations of jazz, but for the uninitiated, here are seven highlights from his 1960s leader albums.

When the world learned of the pioneering saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter's death on March 2, it did so partly through a quote from the maestro itself: "It's time to go get a new body and come back to continue the mission."

This evocation of reincarnation not only speaks to Shorter's elaborate psychospiritual universe — he followed Nichiren Buddhism for half a century — but his multitudes as an artistic behemoth. In his 89-year life, Shorter irrevocably altered so many sectors of jazz and related forms that he seemed to inhabit many bodies at once.

To trace the 12-time GRAMMY winner's artistic evolution is to tell the story of the music as it evolved and propagated through the latter half of the 20th century. He was a member of two of the most crucial groups in jazz history: the brilliant, hotheaded drummer Art Blakey's unofficial jazz academy the Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis' so-called Second Great Quintet.

But even that's just the tip of the iceberg. After an astonishing run of leader albums on Blue Note — including all-timers like JuJu, Speak No Evil and The All Seeing Eye — Shorter formed Weather Report, a fundamental group in '70s and '80s jazz fusion. Along the way, he also collaborated with AOR legends — Joni Mitchell on a slew of mid-period records, and on the title track to Aja, Steely Dan.

In the 21st century, he continued hurtling forward as a composer, and work only seemed to grow more eclectic and multifarious, arguably culminating with (Iphigenia), an expansive opera co-created with bassist and vocalist Esperanza Spalding. At the 2023 GRAMMYs, he won Best Improvised Jazz Solo alongside pianist Leo Genovese for "Endangered Species," a cut on Live at the Detroit Jazz Festival, which also features Spalding and drummer Terri Lyne Carrington.

In 2015, the Recording Academy bestowed upon him a Lifetime Achievement Award. "Wayne Shorter's influence on the jazz community has left an indelible mark on the music industry," Harvey Mason jr., CEO of the Recording Academy, said in part. "It's been a privilege to celebrate his contributions to our culture throughout his incredible career."

As bandleader Darcy James Argue put it, "There isn't a jazz composer today who does not owe an absolutely immeasurable debt to Wayne Shorter. Whether you assimilated his harmonic language, or consciously rejected it, or tried to thread a path somewhere in between, his influence is as unavoidable as the elements."

But with this vast cosmology established, how can Shorter neophytes find their own way in? To traverse the universe of the self-dubbed Mr. Weird — from a line about person or thing X being “as weird as Wayne” — one need not enter it at random.

Arguably, the gateway is Shorter's aforementioned '60s run as a leader; from there, one can venture out in a dozen directions and be rewarded with a lifetime of cerebrality and majesty.

So, for those looking for a way in, here are seven essential tracks from that specific period and component of Shorter's culture-quaking legacy.

"Night Dreamer" (Night Dreamer, 1964)

Shorter was terrific as a leader from the jump, but he arguably came into his own with his fourth album under his own name, Night Dreamer. Much of this had to do with paring down his compositions to their haunting essence. "I used to see a lot of chord changes, for instance, but now I can separate the wheat from the chaff," Shorter said at the time.

Immerse yourself into the fittingly crepuscular title track, which Shorter crafted for a nighttime brood. "The minor keys often connotes evening or night to me," he wrote in the liner notes. "Although the beat does float, it also is set in a heavy groove. It's a paradox, in a way — like you'd have in a dream, something that's both light and heavy."

"Juju" (Juju, 1965)

Night Dreamer and Juju feature a rhythm section closely associated with John Coltrane — the classic Olé Coltrane one, composed of pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Elvin Jones.

As a tenorist influenced by Coltrane, Shorter invited comparisons to his inspiration. But alongside Trane's accompanists, he had developed his own style — with the raw, unvarnished quality of said legend, but a barer tone and more elliptical sense of articulation. Juxtaposed against his accompanists' dazzling, shattered-glass approach, the side-eyeing Shorter is enchanting.

"House of Jade" (Juju, 1965)

After the rainshower of piano notes that initiates "House of Jade," Shorter demonstrates his inimitable way with a ballad, hung on Jones' weighty swing and sway. As jazz author and columnist Mark Stryker put it in an edifying Twitter thread compiling the best of Shorter at a gentler pace: "The ballads are everything. It's all there, now and forever."

"Indian Song" (Etcetera, rec. 1965 rel. 1980)

Featuring bassist Cecil McBee, drummer Joe Chambers, and harmonic mastermind Herbie Hancock — Shorter's lifelong ride-or-die — on piano, Etcetera was recorded the same year as Juju but remained on the shelf for a decade. Better late than never: it stands tall among Shorter's Blue Notes of its time.

All five tracks are fantastic — four Shorters, one Gil Evans, in "Barracudas (General Assembly)." But regarding its final track, "Indian Song," one reviewer might have hit the nail on the head: "At times the rest of the album seems like a warm-up for that amazing tune."

Across more than 11 minutes, "Indian Song" expands and retracts, inhales and exhales, on a spectral path into the unknown. Want an immediate example of how Shorter and Hancock twinned and intertwined their musical spirits to intoxicating effect? Look no further.

"Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum" (Speak No Evil, 1966)

As per compositional mastery, evocative interplay and plain old vibe, Speak No Evil represents something of an apogee for Shorter — and many in the know regard it as the crown jewel.

The majestic, mid-tempo "Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum" is just one highlight of this quintessential, classic-stuffed Blue Note. Hear how Hancock's elusive harmonic shades and Shorter's simple yet impassioned approach just gel — with support from trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Elvin Jones.

"Wayne isn't playing the changes, but plays around the composition—he's creative within the composition," saxophonist David Sanchez once explicated. "[It's] distinct from a lot of other Blue Note recordings of the period on which, generally speaking, people would improvise on the changes once the head or theme was over."

But you don't need to know what's under the hood to hear how this classic thrillingly pushes and pulls.

"Infant Eyes" (Speak No Evil, 1966)

"Infant Eyes" is a Shorter ballad of almost surreal atmosphere and beauty: on a compositional and emotional level, it's difficult to compare it to much else. It's "doom jazz" decades before that was ever a thing.

Down to Shorter's sheer note choices and the grain of his tone, "Infant Eyes" will make your heart leap into your throat. As per Stryker's Twitter litany of enchanting Shorter ballads, the combination is stiff — but if one is supreme, it's difficult to not pick this one.

"Footprints" (Adam's Apple, 1967)

This loping waltz-not-waltz from 1967's Adam's Apple is one of Shorter's most well-known tunes; even without close analysis of its sneaky rhythms, it's downright irresistible. And talk about gateways: it's a launchpad for any young musician who wants to give his tunes a shot.

"Footprints" continues to be a standard; it titled his biography; the Facebook post announcing Shorter's death bore footprint emojis. Shorter may have transitioned from this body, but his impressions are everywhere — and we'll never see the likes of Mr. Weird again.

No Accreditation? No Problem! 10 Potential Routes To Get Into Jazz As A Beginner

Photo: Rachel Kupfer

list

A Guide To Modern Funk For The Dance Floor: L'Imperatrice, Shiro Schwarz, Franc Moody, Say She She & Moniquea

James Brown changed the sound of popular music when he found the power of the one and unleashed the funk with "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." Today, funk lives on in many forms, including these exciting bands from across the world.

It's rare that a genre can be traced back to a single artist or group, but for funk, that was James Brown. The Godfather of Soul coined the phrase and style of playing known as "on the one," where the first downbeat is emphasized, instead of the typical second and fourth beats in pop, soul and other styles. As David Cheal eloquently explains, playing on the one "left space for phrases and riffs, often syncopated around the beat, creating an intricate, interlocking grid which could go on and on." You know a funky bassline when you hear it; its fat chords beg your body to get up and groove.

Brown's 1965 classic, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," became one of the first funk hits, and has been endlessly sampled and covered over the years, along with his other groovy tracks. Of course, many other funk acts followed in the '60s, and the genre thrived in the '70s and '80s as the disco craze came and went, and the originators of hip-hop and house music created new music from funk and disco's strong, flexible bones built for dancing.

Legendary funk bassist Bootsy Collins learned the power of the one from playing in Brown's band, and brought it to George Clinton, who created P-funk, an expansive, Afrofuturistic, psychedelic exploration of funk with his various bands and projects, including Parliament-Funkadelic. Both Collins and Clinton remain active and funkin', and have offered their timeless grooves to collabs with younger artists, including Kali Uchis, Silk Sonic, and Omar Apollo; and Kendrick Lamar, Flying Lotus, and Thundercat, respectively.

In the 1980s, electro-funk was born when artists like Afrika Bambaataa, Man Parrish, and Egyptian Lover began making futuristic beats with the Roland TR-808 drum machine — often with robotic vocals distorted through a talk box. A key distinguishing factor of electro-funk is a de-emphasis on vocals, with more phrases than choruses and verses. The sound influenced contemporaneous hip-hop, funk and electronica, along with acts around the globe, while current acts like Chromeo, DJ Stingray, and even Egyptian Lover himself keep electro-funk alive and well.

Today, funk lives in many places, with its heavy bass and syncopated grooves finding way into many nooks and crannies of music. There's nu-disco and boogie funk, nodding back to disco bands with soaring vocals and dance floor-designed instrumentation. G-funk continues to influence Los Angeles hip-hop, with innovative artists like Dam-Funk and Channel Tres bringing the funk and G-funk, into electro territory. Funk and disco-centered '70s revival is definitely having a moment, with acts like Ghost Funk Orchestra and Parcels, while its sparkly sprinklings can be heard in pop from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, and, in full "Soul Train" character, Silk Sonic. There are also acts making dreamy, atmospheric music with a solid dose of funk, such as Khruangbin’s global sonic collage.

There are many bands that play heavily with funk, creating lush grooves designed to get you moving. Read on for a taste of five current modern funk and nu-disco artists making band-led uptempo funk built for the dance floor. Be sure to press play on the Spotify playlist above, and check out GRAMMY.com's playlist on Apple Music, Amazon Music and Pandora.

Say She She

Aptly self-described as "discodelic soul," Brooklyn-based seven-piece Say She She make dreamy, operatic funk, led by singer-songwriters Nya Gazelle Brown, Piya Malik and Sabrina Mileo Cunningham. Their '70s girl group-inspired vocal harmonies echo, sooth and enchant as they cover poignant topics with feminist flair.

While they’ve been active in the New York scene for a few years, they’ve gained wider acclaim for the irresistible music they began releasing this year, including their debut album, Prism. Their 2022 debut single "Forget Me Not" is an ode to ground-breaking New York art collective Guerilla Girls, and "Norma" is their protest anthem in response to the news that Roe vs. Wade could be (and was) overturned. The band name is a nod to funk legend Nile Rodgers, from the "Le freak, c'est chi" exclamation in Chic's legendary tune "Le Freak."

Moniquea

Moniquea's unique voice oozes confidence, yet invites you in to dance with her to the super funky boogie rhythms. The Pasadena, California artist was raised on funk music; her mom was in a cover band that would play classics like Aretha Franklin’s "Get It Right" and Gladys Knight’s "Love Overboard." Moniquea released her first boogie funk track at 20 and, in 2011, met local producer XL Middelton — a bonafide purveyor of funk. She's been a star artist on his MoFunk Records ever since, and they've collabed on countless tracks, channeling West Coast energy with a heavy dose of G-funk, sunny lyrics and upbeat, roller disco-ready rhythms.

Her latest release is an upbeat nod to classic West Coast funk, produced by Middleton, and follows her February 2022 groovy, collab-filled album, On Repeat.

Shiro Schwarz

Shiro Schwarz is a Mexico City-based duo, consisting of Pammela Rojas and Rafael Marfil, who helped establish a modern funk scene in the richly creative Mexican metropolis. On "Electrify" — originally released in 2016 on Fat Beats Records and reissued in 2021 by MoFunk — Shiro Schwarz's vocals playfully contrast each other, floating over an insistent, upbeat bassline and an '80s throwback electro-funk rhythm with synth flourishes.

Their music manages to be both nostalgic and futuristic — and impossible to sit still to. 2021 single "Be Kind" is sweet, mellow and groovy, perfect chic lounge funk. Shiro Schwarz’s latest track, the joyfully nostalgic "Hey DJ," is a collab with funkstress Saucy Lady and U-Key.

L'Impératrice

L'Impératrice (the empress in French) are a six-piece Parisian group serving an infectiously joyful blend of French pop, nu-disco, funk and psychedelia. Flore Benguigui's vocals are light and dreamy, yet commanding of your attention, while lyrics have a feminist touch.

During their energetic live sets, L'Impératrice members Charles de Boisseguin and Hagni Gwon (keys), David Gaugué (bass), Achille Trocellier (guitar), and Tom Daveau (drums) deliver extended instrumental jam sessions to expand and connect their music. Gaugué emphasizes the thick funky bass, and Benguigui jumps around the stage while sounding like an angel. L’Impératrice’s latest album, 2021’s Tako Tsubo, is a sunny, playful French disco journey.

Franc Moody

Franc Moody's bio fittingly describes their music as "a soul funk and cosmic disco sound." The London outfit was birthed by friends Ned Franc and Jon Moody in the early 2010s, when they were living together and throwing parties in North London's warehouse scene. In 2017, the group grew to six members, including singer and multi-instrumentalist Amber-Simone.

Their music feels at home with other electro-pop bands like fellow Londoners Jungle and Aussie act Parcels. While much of it is upbeat and euphoric, Franc Moody also dips into the more chilled, dreamy realm, such as the vibey, sultry title track from their recently released Into the Ether.