Photo: Courtesy of Apple TV+

The Velvet Underground

news

Watch New 'The Velvet Underground' Documentary Trailer From Apple TV+

The upcoming Todd Haynes-directed documentary chronicles the Velvet Underground’s upstart in the 1960s and their eventual global superstardom

Today, Apple TV+ unveiled the first trailer for The Velvet Underground, a long-awaited documentary about the New York City rock band beloved for their unapologetic sound and experimental high art appeal.

Arriving in select theaters and Apple TV+ on Oct. 15, the film features never-before-seen performances, interviews with surviving group members, music recordings and segments of Andy Warhol collaborations. Accompanying the film is a two-disc and digital soundtrack of legendary tracks and rarities by The Velvet Underground, curated by the film’s director Todd Haynes—his debut documentary—and music supervisor Randall Poster. Known for his experimental touch behind musical films I’m Not There and Velvet Goldmine, Haynes is sure to bring the same immersive experience to The Velvet Underground.

An Official Selection of Festival de Cannes 2021, The Velvet Underground follows the band’s roots from New York City underground street culture to the mainstream through their presence in music and pop art.

The film follows a series of music documentaries featured on Apple TV+, including Beastie Boys Story, Aretha Franklin’s 1972 gospel return Amazing Grace and Billie Eilish documentary The World’s A Little Blurry.

Remembering The Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts: 5 Essential Performances By The Drum Legend

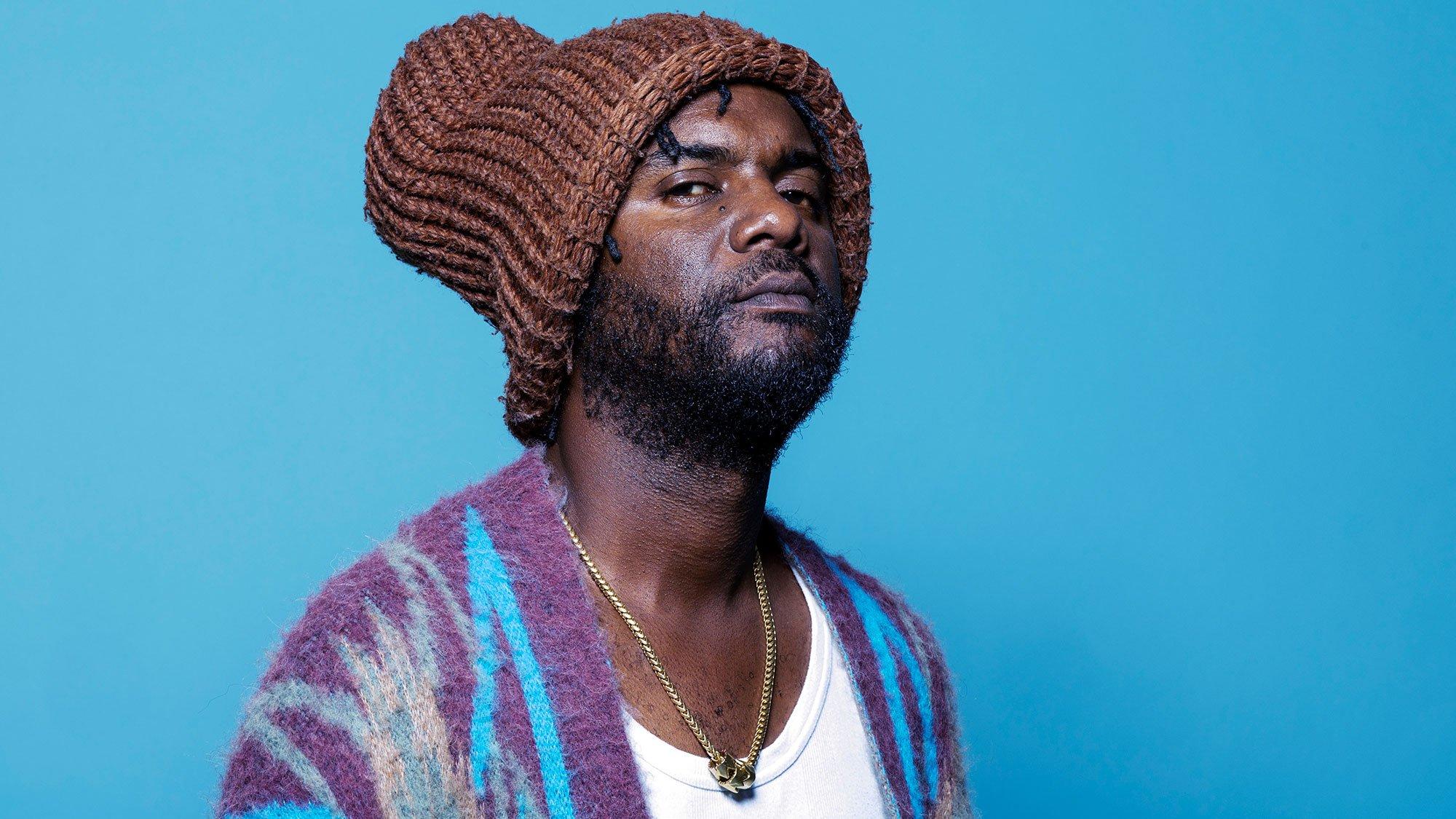

Photo: Mike Miller

interview

Gary Clark, Jr. On 'JPEG RAW': How A Lockdown Jam Session, Bagpipes & Musical Manipulation Led To His Most Eclectic Album Yet

Gary Clark, Jr.'s latest record, 'JPEG RAW,' is an evolution in the GRAMMY-winning singer and guitarist's already eclectic sound. Clark shares the process behind his new record, which features everything from African chants to a duet with Stevie Wonder.

Stevie Wonder once said "you can’t base your life on people’s expectations." It’s something guitarist and singer Gary Clark, Jr. has taken to heart as he’s built his own career.

"You’ve got to find your own thing," Clark tells GRAMMY.com.

Clark recently duetted with Wonder on "What About The Children," a song on his forthcoming album. Out March 22, JPEG RAW sees Clark continue to evolve with a mixtape-like kaleidoscope of sounds.

Over the years, Clark has ventured into rock, R&B, hip-hop blues, soul, and country. JPEG RAW is the next step in Clark's eclectic sound and sensibility, the result of a free-flowing jam session held during COVID-19 lockdown. Clark and his bandmates found freedom in not having a set path, adding elements of traditional African music and chants, electronic music, and jazz into the milieu.

"We just kind of took it upon ourselves to find our own way and inspire ourselves," says Clark, a four-time GRAMMY winner. "And that was just putting our heads together and making music that we collectively felt was good and we liked, music we wanted to listen to again."

The creation process was simultaneously freeing and scary.

"It was a little of the unknown and then a sense of hope, but also after there was acceptance and then it was freeing. I was like, all right, well, I guess we’re just doing this," Clark recalls. "It was an emotional, mental rollercoaster at that time, but it was great to have these guys to navigate through it and create something in the midst of it."

JPEG RAW is also deeply personal, with lyrics reflecting on the future for Clark himself, his family, and others around the globe. While Clark has long reflected on political and social uncertainties, his new release widens the lens. Songs like "Habits" examine a universal humanity in his desire to avoid bad habits, while "Maktub" details life's common struggles and hopes.

Clark and his band were aided in their pursuit by longtime collaborator and co-producer Jacob Sciba and a wide array of collaborators. Clark’s prolific streak of collaborations continued, with the album also featuring funk master George Clinton, electronic R&B/alt-pop artist Naala, session trumpeter Keyon Harrold, and Clark’s sisters Shanan, Shawn, and Savannah. He also sampled songs by Thelonious Monk and Sonny Boy Williamson.

Clark has also remained busy as an actor (he played American blues legend Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis) and as a music ambassador (he was the Music Director for the 23rd Annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor).

GRAMMY.com recently caught up with Clark, who will kick off his U.S. tour May 8, about his inspirations for JPEG RAW, collaborating with legendary musicians, and how creating music for a film helped give him a boost of confidence in the studio.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You incorporated traditional African music on JPEG RAW. How did it affect your songwriting process?

Well, I think traveling is how it affected my songwriting process. I was over in London, and we played a show with Songhoy Blues, and I was immediately influenced. I was like, "dang, these are my musical brothers from all the way across the world."

I always kind of listened to West African funk and all that kind of stuff. So, I was just listening to that in the studio, and just kind of started messing around with the thing. And that just kind of evolved from there. I was later told by Jacob Sciba that he was playing that music trying to brainwash me into leaning more in that direction. I thought we were just genuinely having a good time exploring music together, and he was trying to manipulate me. [Laughs.]

I quit caring about what people thought about me wanting to be a certain thing. I think that being compared to Jimi Hendrix is a blessing and a curse for me because I'm not that. I will never be that. I never wanted to imitate or copy that, no disrespect.

You’ve got to find your own thing. And my own thing is incorporating all the styles of music that I love, that I grew up on, and [was] influenced by as a pre-teen/teenager. To stay in one space and just be content doing that has never been my personality ever…I do what I like.

I read that you play trumpet at home and also have a set of bagpipes, just in case the mood strikes.

I used to go collect instruments and old cameras from thrift stores and vintage shops and flea markets. So, I saw some bagpipes and I just picked them up. I've got a couple of violins. I don't play well at all — if you could consider that even playing. I've got trumpet, saxophone, flutes, all kinds of stuff just in case I can use these instruments in a way that'll make me think differently about music. It'll inspire me to go in a different direction that I've maybe never explored before, or I can translate some of that into playing guitar.

One of my favorite guitarists, Albert Collins, was really inspired by horn players. So, if you can understand that and apply that to your number one instrument, maybe it could affect you.

Given recent discussions about advancements in AI and our general inundation with technology, the title of your album is very relevant. What about people seeing life through that filter concerns you? Why does the descriptor seem apt?

During the pandemic, since I wasn't out in the world, I was on my phone and the information I was getting was through whatever social media platforms and what was going on in certain news outlets, all the news outlets. I'm just paying attention and I'm just like, man, there's devastation.

I realized that I don't have to let it affect me. Just because things are accessible doesn't mean that you need to [access them]. It just made me think that I needed to do less of this and more of being appreciative of my world that's right in front of me, because right now it is really beautiful.

You’ve said the album plays out like a film, with a wide range of emotions throughout. What was it like seeing the album have that film-like quality?

I had conversations with the band, and I'd expressed to them that I want to be able to see it. I want to be able to see it on film, not just hear it. Keyboardist Jon Deas is great with [creating a] sonic palate and serving a mood along with [Eric] "King" Zapata who plays [rhythm] guitar. What he does with the guitar, it serves up a mood to you. You automatically see a color, you see a set design or something, and I just said, "Let's explore that. Let's make these things as dense as possible. Let's go like Hans Zimmer meets John Lee Hooker. Let's just make big songs that kind of tell some sort of a story."

Also, we were stuck to our own devices, so we had to use our imagination. There was time, there was no schedule. So, we were free, open space, blank canvas.

The album opens with "Maktub," which is the Arabic word for fate or destiny. How has looking at different traditions given you added clarity with looking at what's happening here in the U.S.?

I was sitting in the studio with Jacob Sciba and my friend Sama'an Ashrawi and we were talking about the history of the blues. And then we started talking about the real history of the blues, not just in its American form, in an evolution back to Africa. You listen to a song like "Maktub," and then you listen to a song like, "Baby What You Want Me to Do" by Jimmy Reed….

The last record was This Land, but what about the whole world? What about not just focusing on this, but what else is going on out there? And we drew from these influences. We talked about family, we talked about culture, we talked about tradition, we talked about everything. And it's like, let's make it inclusive, build the people up. Let's build ourselves up. It’s not just about your small world, it’s about everybody’s feelings. Sometimes they're dealt with injustice and devastation everywhere, but there's also this global sense of hope. So, I just wanted to have a song that had the sentiment of that.

I really enjoyed the song’s hopeful message of trying to move forward.

Obviously, things are a little bit funky around here, and I don't have any answers. But maybe if we got our heads together and brainstorm, we could all figure something out instead of … struggling or suffering in silence. It's like, let's find some light here.

But part of the talks that I had with Sama'an and his parents over a [video] call was music. He’s from Palestine, and growing up music was a way to connect. Music was a way to find happiness in a place where that wasn't an everyday convenience, and that was really powerful. That music is what brought folks together and brought joy and built a community and a common way of thinking globally. They were listening to music from all over the world, American music, rock music, and that was an influence.

The final song on the album, "Habits," sounds like it was the most challenging song to put together. What did you learn from putting that song together?

Well, that song originally was a bunch of different pieces, and I thought that they were different songs, and I was singing the different parts to them, and then I decided to put them all together. I think I was afraid to put them all together because we were like, "let's not do these long self-indulgent pieces of music. Let's keep it cool." But once I put these parts together and put these lyrics together, it just kind of made sense.

I got emotional when I was singing it, and I was like, This is part of using this as an outlet for the things that are going on in life. We went and recorded it in Nashville with Mike Elizondo and his amazing crew, and it's like, yep, we're doing it all nine minutes of it.

You collaborated with a bunch of musicians on this album, including Naala on "This Is Who We Are." What was that experience like?

Working with Naala was great. That song was following me around for a couple of years, and I knew what I wanted it to sound like, but I didn't know how I was going to sing it. I had already laid the musical bed, and I think it was one of the last songs that we recorded vocals on for the album.

Lyrically, it’s like a knight in shining armor or a samurai, and there's fire and there's war, and this guy's got to go find something. It was like this medieval fairytale type thing that I had in my head. Naala really helped lyrically guide me in a way that told that story, but was a little more personal and a little more vulnerable. I was about to give up on that song until she showed up in the studio.

"What About the Children" is based on a demo that you got from Stevie Wonder. You got to duet with him, what was that collaboration like?

Oh, it was great. It was a life-changing experience. The guy's the greatest in everything, he was sweet, the most talented, hardworking, gracious, humble, but strong human being I've been in a room with and been able to create with.

I was in shock when I left the studio at how powerful that was and how game changing and eye-opening it was. It was educational and inspiring. It was like before Stevie and after Stevie.

I imagine it was also extra special getting to have your sisters on the album.

Absolutely. We got to sing with Stevie Wonder; we used to grow up listening to George Clinton. They've stuck with us throughout my whole life. So, to be able to work with him and George Clinton — they came in wanting to do the work, hardworking, badass, nice, funny — it was a dream.

Stevie Wonder and George Clinton are just different. They're pioneers and risk takers. For a young Black kid from Texas to see that and then later to be able to be in a room with that and get direct education and conversation…. It's an experience that not everybody gets to experience, and I'm grateful that I did, and hopefully we can do it again.

In 2022, you acted in Elvis. What are the biggest things you've learned from expanding into new creative areas?

I really have to give it up to a guy named Jeremy Grody…I went to his studio with these terrible demos that I had done on Pro Tools…and this guy helped save them and recreate them. I realized the importance of quality recordings. Jeremy Grody was my introduction to the game and really set me up to have the confidence to be able to step in rooms like that again.

I played some songs in the film, and I really understood how long a film day was. It takes all day long, a lot of takes, a lot of lights, a lot of big crews, big production.

I got to meet Lou Reed [while screening the film] at the San Sebastian Film Festival, and I was super nervous in interviews. I was giving away the whole movie. And Lou Reed said, "Just relax and have fun with all this s—." I really appreciated that.

Do you have a dream role?

I don't have a dream role, but I do know that if I was to get into acting, I’d really dive into it. I would want to do things that are challenging. I like taking risks. I want to push it to the limit. I would really like to understand what it's like to immerse yourself in the character and in the script and do it for real.

You're about to go out on tour. How will the show and production on this tour compare with the past ones?

We're building it currently, but I'm excited about what we got in store as far as the band goes. There are a few additions. I've got my sisters coming out with me. It's just going to be a big show.There's a new energy here, and I'm excited to share that with folks.

Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Kendrick Lamar Honors Hip-Hop's Greats While Accepting Best Rap Album GRAMMY For 'To Pimp a Butterfly' In 2016

Upon winning the GRAMMY for Best Rap Album for 'To Pimp a Butterfly,' Kendrick Lamar thanked those that helped him get to the stage, and the artists that blazed the trail for him.

Updated Friday Oct. 13, 2023 to include info about Kendrick Lamar's most recent GRAMMY wins, as of the 2023 GRAMMYs.

A GRAMMY veteran these days, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 47 GRAMMY nominations overall. A sizable chunk of his trophies came from the 58th annual GRAMMY Awards in 2016, when he walked away with five — including his first-ever win in the Best Rap Album category.

This installment of GRAMMY Rewind turns back the clock to 2016, revisiting Lamar's acceptance speech upon winning Best Rap Album for To Pimp A Butterfly. Though Lamar was alone on stage, he made it clear that he wouldn't be at the top of his game without the help of a broad support system.

"First off, all glory to God, that's for sure," he said, kicking off a speech that went on to thank his parents, who he described as his "those who gave me the responsibility of knowing, of accepting the good with the bad."

Looking for more GRAMMYs news? The 2024 GRAMMY nominations are here!

He also extended his love and gratitude to his fiancée, Whitney Alford, and shouted out his Top Dawg Entertainment labelmates. Lamar specifically praised Top Dawg's CEO, Anthony Tiffith, for finding and developing raw talent that might not otherwise get the chance to pursue their musical dreams.

"We'd never forget that: Taking these kids out of the projects, out of Compton, and putting them right here on this stage, to be the best that they can be," Lamar — a Compton native himself — continued, leading into an impassioned conclusion spotlighting some of the cornerstone rap albums that came before To Pimp a Butterfly.

"Hip-hop. Ice Cube. This is for hip-hop," he said. "This is for Snoop Dogg, Doggystyle. This is for Illmatic, this is for Nas. We will live forever. Believe that."

To Pimp a Butterfly singles "Alright" and "These Walls" earned Lamar three more GRAMMYs that night, the former winning Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song and the latter taking Best Rap/Sung Collaboration (the song features Bilal, Anna Wise and Thundercat). He also won Best Music Video for the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood."

Lamar has since won Best Rap Album two more times, taking home the golden gramophone in 2018 for his blockbuster LP DAMN., and in 2023 for his bold fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.

Watch Lamar's full acceptance speech above, and check back at GRAMMY.com every Friday for more GRAMMY Rewind episodes.

10 Essential Facts To Know About GRAMMY-Winning Rapper J. Cole

Photo: Gus Stewart/Getty Images

feature

Lou Reed's 'Berlin' Is One Of Rock's Darkest Albums. So Why Does It Sound Like So Much Fun?

Lou Reed's third album is a harrowing examination of addiction, abuse and suicide. Yet the bleakness lands because it's so beautifully counterweighted.

Lou Reed's Berlin begins with a nightmarishly tape-destroyed German count-in — eins, zwei, drei, zugabe — followed by the "Happy Birthday" song. It ends with a bloody suicide in a bed.

Wait, that's the second-to-last track; Berlin actually ends as the narrator callously brushes off said suicide — which happened to be of the mother of his children. The lynchpin track, "The Kids," features a harrowing soundbite of children screaming for their mother.

In between, Reed relates the tale of a relationship that spins out into addiction, prostitution and domestic abuse against the backdrop of the titular city — which, at the time, Reed had never been to.

Berlin profoundly alienated some critics. Rolling Stone castigated it as one of "certain records so patently offensive that one wishes to take some kind of physical vengeance on the artists that perpetrate them...a distorted and degenerate demimonde of paranoia, schizophrenia, degradation, pill-induced violence and suicide."

Likewise, Robert Christgau called the notion of Berlin's artistic accomplishment "horses—" and added that the story of the couple "lousy," with the ambitious, operatic music "only competent." By all accounts, the incomprehension hurt Reed; he pulled a 180 with 1974's glammy Sally Can't Dance.

But despite the content, and the chaos in Reed's personal life at the time — fathoms of drugs, a failing marriage — Berlin is no druggie disaster. In reality, it's one of the crown jewels of the GRAMMY winner's voluminous discography, and a masterclass in finding beauty in the sordid depths of the human condition.

And it's difficult to imagine Berlin's story landing without utterly gonzo music — and a fair amount of ink-black humor.

The key to the former is the GRAMMY-nominated producer Bob Ezrin, who's helped craft any number of epic, ridiculous, fall-on-your-face rock classics. Case in point: a year prior to Berlin, he'd produced Alice Cooper's School's Out; just after, he'd helm Aerosmith's Get Your Wings.

Berlin followed 1972's Transformer — his second album and breakthrough, by way of the epochal "Walk on the Wild Side." Both the album and single's successes were helped along by a very high-profile producer — an ascendant David Bowie.

But as Anthony DeCurtis lays out in his 2017 biography Lou Reed: A Life, Bowie had been attracting credit for Transformer, and Reed started to look like his imitator.

"From the industry perspective, the aesthetic differences between Bowie, Reed and Cooper were meaningless," DeCurtis explains in the book. "Broadly speaking, they were all working the same side of the street — bending gender categories and stunning conventional sensibilities."

Given this perception — and a brawl they'd undergone in a London club over Reed's habits — it was time for Reed to untether from Bowie, just as the latter launched into the stratosphere.

"Lou is out of the glitter thing. He really denounces it," crowed Reed's manager at the time, Dennis Katz. "He's not interested in glam rock or glitter rock. Lou Reed is a rock and roller." Reed and Katz went with the 23-year-old Ezrin, who was riding high on Alice Cooper's success — and seemed like the obvious choice.

With the success of Transformer in the rearview, Ezrin and Reed felt emboldened to devise a work of boundless aspiration. It would be a rock opera — a double concept album with an elaborate booklet, with photographs that depict the downfall of the central couple, Caroline and Jim.

Ezrin booked a wild backing ensemble — including keyboardist Steve Winwood of the Spencer Davis Group, Blind Faith and Traffic; bassist Jack Bruce of Cream; drummer B.J. Wilson of Procol Harum; and Michael and Randy Brecker, respectively on tenor sax and trumpet. As the sessions rolled on, hype broiled around the project.

"It's not an overstatement to say that Berlin will be the Sgt. Pepper of the seventies," blustered Larry "Ratso" Sloman in Rolling Stone. Which is laughable today — but it helps frame Berlin in its time and context.

"When people thought of a concept album, they thought Sgt. Pepper," singer/songwriter Elliott Murphy, who befriended Reed around this period, tells GRAMMY.com. "And Berlin is kind of the Antichrist of Sgt. Pepper."

Just as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band used childhood and nostalgia as a launching pad rather than a set of rigid parameters, Berlin — which ended up being a single-disc release — doesn't simply bludgeon you with misery for 49 minutes.

Berlin takes flower from its title track, a barely-there sketch of a romantic scene in the titular city, originally released on Reed's self-titled 1972 debut. As DeCurtis opines in Lou Reed: A Life, "Perhaps it was the song's unfinished quality that appealed to them, leaving space for them to fill with their fantasies of what it might become."

Whatever the case, Reed had a natural facility for expansive narratives. As author Will Hermes explains, Reed's early "mentor and model" was Delmore Schwartz, his English professor at Syracuse University.

"There's humor and there's pathos in equal parts," says Hermes, whose sprawling, fascinating biography, Lou Reed: The King of New York, was released Oct. 3. He's referring to Schwartz and his work, but this extends to his mentee: "Reed was a hilarious guy, from everybody I spoke to, and certainly reading his interviews. So that darkness and humor came together. I don't think a lot of people got that about Berlin when it was first produced."

Reed had taken a theater class at Syracuse, loved Federico Fellini in college, and remained a cinephile for life. By its very nature, the episodic, operatic format of Berlin precludes monotony; each song examines this doomed coupling from a different angle.

Sure, every facet of the Berlin tale is cursed. But Reed explains why it's cursed — including from Jim and Caroline's warring perspectives, as on "Jim Says," "Caroline I" and "II" and beyond. Which gives it innate narrative variety, as the listener ping-pongs through the sordid tale.

"'The Bed' and 'The Kids' are very powerful experiences, but not really a hoot," Stickles says of Berlin's B-side. "But the A-side is a pretty big hoot. Like, 'Caroline Says I' rocks. 'How Do You Think It Feels' — these are fun, big rockers, and it's got the funny flutes and clarinets as well."

And while Reed is unflinching in his depictions of violence and suffering, that quality doesn't render him a bore on Berlin — Reed being Reed, it makes him a live wire.

"Berlin is not that one-dimensional; it's not a single-note record," singer/songwriter and Reed head Jerry David DeCicca, who's just released his latest album New Shadows, tells GRAMMY.com. "It might be shades of some of those things, but that's what makes it interesting."

This eclecticism extends to the music, which never rolls over and cries in its milk, but frequently detonates with goofy, stadium-sized, Meat Loaf-esque jubilance. But despite its pedigree and context within a specific chapter of hard rock, Berlin sounds oddly singular.

Patrick Stickles, the lead singer of the rock band Titus Andronicus and a Reed acolyte, calls Berlin "far more proggy than your typical Lou Reed material."

"It's very ornate, but it doesn't really sound like Yes or King Crimson or whatever was going on at that time," Stickles tells GRAMMY.com," because he's still writing with his favorite two or three chords."

"It just doesn't sound like a lot of records from that time period," DeCicca says. "So I don't think he was trying to fit in."

DeCicca then considers the wider scope of Reed's catalog: "He made another record after that, the next year, that was just incredibly different [Sally Can’t Dance]. Which I'm sure was in some part a reaction to it. But how conscious or unconscious is probably a little bit debatable. I mean, he was not somebody who wanted to repeat himself."

In the end, Berlin resonates due to Reed's boundless audacity — and the sheer oddness that permeates its grooves, from start to finish.

"That's probably his No. 1 virtue as a writer — that he always goes there," GRAMMY nominee Will Sheff, who's struck out solo after two decades fronting Okkervil River, tells GRAMMY.com. "I think his main innovation is that he took the guardrails off of subject matter." (Tonalities, too: whether this was intentional or not, Sheff calls 1967's The Velvet Underground & Nico "one of the most f—ed up, cheap, amateurish things that you've ever heard.")

Sheff and his Okkervil River bandmates clung to Berlin during desperate, ragged tours of yore: today, he marvels at the contradictions of its studio dynamic.

"Based on a lot of the accounts, it sounds a little bit like Bob Ezrin was kind of dragging him through the process of making it," Sheff says. "It kind of sounds like a f—ed up, surly, stuck in molasses guy, who's being sort of dragged out of bed and forced into the studio, where there's a string section waiting for him."

(Was Reed on fire in the studio, or being "dragged" by Ezrin? "I think it was a bit of both," Hermes says. "There were a lot of drugs and alcohol involved, but they were working really hard, being really ambitious.")

However checked out Reed was or wasn't, Ezrin brought his consummate showmanship to the party. "And that's part of what makes Berlin fun — he really honors Lou Reed's ambitions, maybe more than Lou was honoring them at the time. I wouldn't call it joyous, but there is a lot very butch [energy], like, 'I'm just a guy strutting down the street in Berlin, and I'm a tough man.' I find that stuff very charming."

Sure, Berlin may be exactly how Sheff describes it: "excessively dark…sick, diseased, kind of broken heart of a masculine anger and sorrow." Against that pitch-black backdrop, every overenthusiastic drumfill, expensive string flourish and brutal joke truly sparkle. (As per the latter: ("This is a bum trip," Caroline complains about domestic battery.)

Despite the sting of critical rejection, Reed continued pursuing long-form, narrative works throughout his career. These included what Hermes calls "three experimental quote-unquote musical theater pieces.") These were with the visionary Robert Wilson — one based on H.G. Wells' The Time Machine, another based on Edgar Allen Poe, and another in Lulu, which germinated into a polarizing 2011 album of the same name with Metallica.

And Reed always felt strongly about Berlin. In 2006, he revived it for a stage show, which would be released two years later as Berlin: Live at St. Ann's Warehouse. As Hermes put it, "The performance was frequently gorgeous and a bitter pill: magnificent, overwrought, pretentious, full of thematic misogyny." In other words, it's a lot — and it deals in far more than you-know-what quality.

"Lots of content in life is depressing," DeCicca says, "but that doesn't mean you write off people's experiences as not being worth engaging with."

Half a century on, Berlin isn't merely worth engaging with — it remains brazen and captivating, a looking glass into the heart of darkness.

Living Legends: John Cale On How His Velvet Underground Days & Love Of Hip-Hop Influenced New Album Mercy

Photo: Edward Wong/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

feature

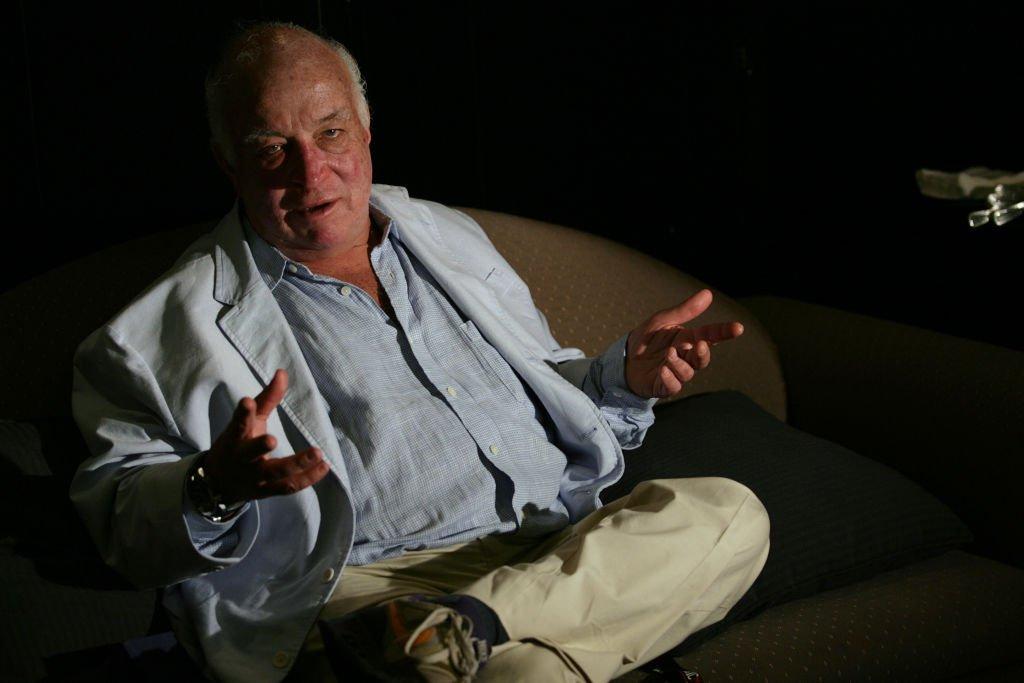

Remembering Seymour Stein: Without The Record Business Giant, Music Would Be Unrecognizable

The music man who signed everyone from the Ramones to Madonna will be profoundly missed throughout the global music community. He passed away on Apr. 8 at 80.

There’s a Belle and Sebastian song titled “Seymour Stein” that evokes a real-life, lavish feast between the soft-spoken Scottish indie band and the record company executive.

In the 1998 ballad, singer Stuart Murdoch details the tension between their working class identities and the dizzying prospects that Stein held in the palm of his hand. “Promises of fame, promises of fortune/ L.A. to New York/ San Francisco, back to Boston,” Murdoch dreamily sings. But he demurs, thinking of a girl back home in the country: “My thoughts are far away.”

There was a very good reason Murdoch and company associated Stein with an almost blindingly paradisiacal vision of music success. For an entire generation of alternative weirdos, Stein — the co-founder of Sire Records and vice president of Warner Bros. Records — was the guy who made it happen.

Sadly, Stein passed away on April 2 at his home in Los Angeles of cancer at the age of 80. This seismic loss to the global music community has rightfully earned tributes from far-flung corners of the music industry. Many, like his signee Madonna, openly pondered where their lives would be without his razor-sharp perception and adoration of all things music.

Think of the three-or-four-chord powderkeg of the Ramones’ 1977 self-titled debut, and the CBGB-adjacent army that answered to its detonation: Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Richard Hell and the Voldoids — on and on. Stein signed them all to Sire, either initiating their careers, as per the Ramones, or heralding their second acts, as he did the Replacements.

That paradigm arguably amounted to the biggest shift in guitar-based music since the Beatles — the ratcheting-down of opulent ‘70s rock into something leaner, meaner, and arguably more honest. But even that’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Stein's influence on music and culture at large.

Stein was the man who signed Madge, a profoundly pivotal figure in the following decade. And the rest of his resume was staggering: the Smiths, the Cure, Seal, k.d. lang, Brian Wilson, Lou Reed, Body Count… the list goes on.

He helped to establish the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, by way of the foundation of the same name, initiated by Ahmet Ertegun in 1983 — and was himself inducted in 2005. In 2018, the Recording Academy bestowed him with a coveted Trustees Award, which acknowledged his decades of service to the music community.

Indeed, the music man’s loss reverberates throughout the world’s leading society of music people.

“Seymour Stein was one of the greatest A&R executives of all time,” Ruby Marchand, the Chief Awards & Industry Officer at the Recording Academy, tells GRAMMY.com. “His passion, magnetic energy and natural curiosity underscored a lifelong dedication to unique artistry.

“He especially prized the art of songwriting and had an encyclopedic knowledge of songs, often bursting out in song to regale and delight friends and colleagues,” recalls Marchand, who worked with Stein for decades. “Seymour traveled the globe for decades and basked in the glow of discovering emerging artists singing to small audiences, from Edmonton to Seoul.

“He was a doting mentor, advisor, cheerleader and advocate for hundreds of us in the industry worldwide,” she concludes. “We cherish him and miss him terribly, and know how fortunate we were to have had him in our lives.”

The Recording Academy hails the late, great Stein for his monumental achievements in the music industry — ones that have fundamentally altered humanity’s universal language forever.

Mogul Moment: How Quincy Jones Became An Architect Of Black Music