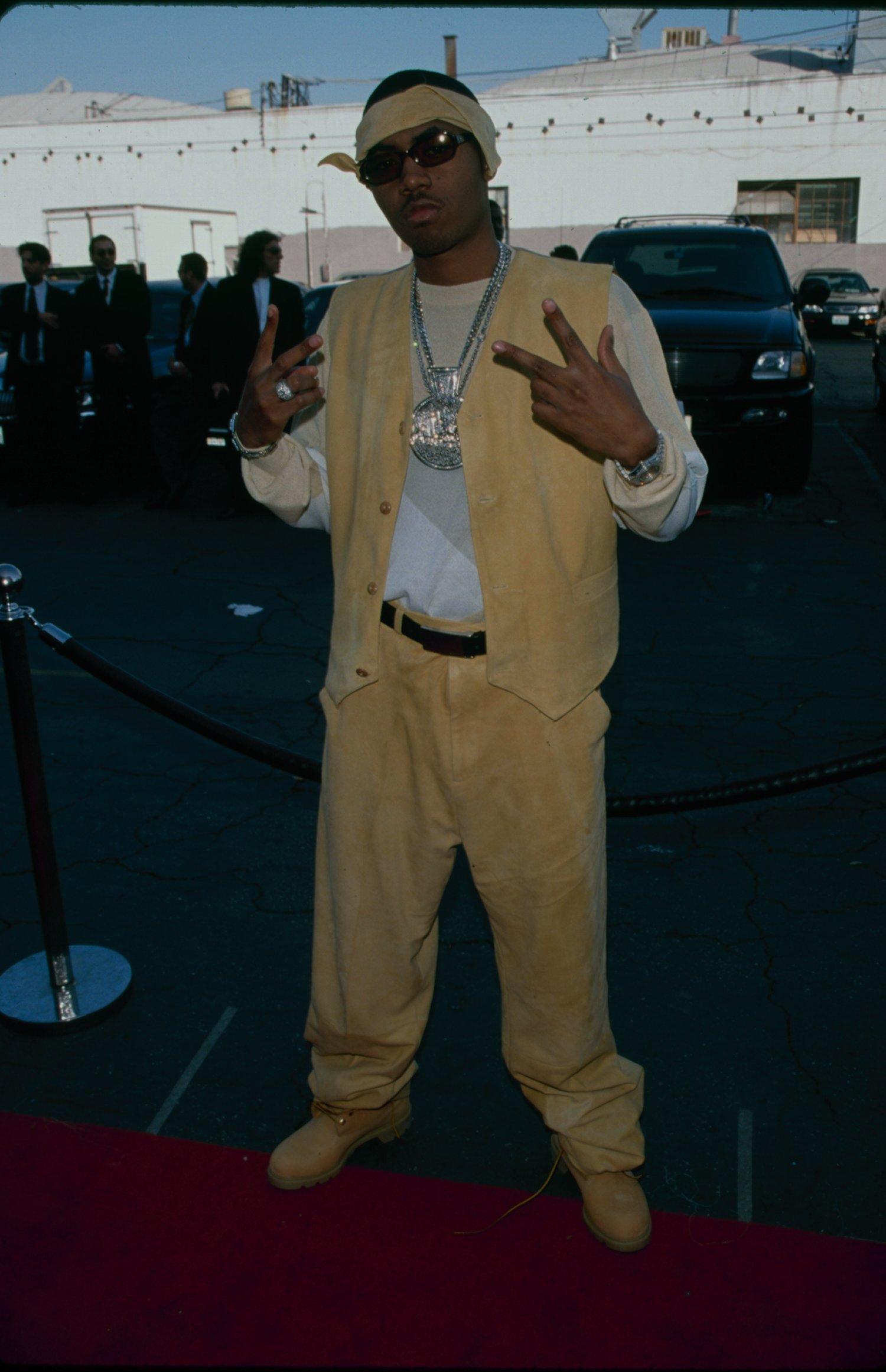

Photo: The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Nas

news

Nas' 'Illmatic' | For The Record

Revisit the streets of New York City in 1994 when the rapper's debut album set the stage for the resurgence of East Coast hip-hop

The GRAMMY-nominated rapper Nas is nothing short of legendary, giving the world plenty of his smooth lyricism and iconic verses in his releases over the years. To date, he has released 11 studio albums, the most recent being the Kanye West-produced Nasir, which dropped this summer as part of West's Wyoming sessions releases. Since the start Nas has been turning heads and paving the way for other hip-hop artists. His debut LP, Illmatic, not only put him firmly on the map, but also provided a revitalization of the East Coast rap sound.

A 20-year-old Nas released his first full-length album, Illmatic on April 19, 1994, to much critical acclaim. Source blessed it with a rare 5 Mic rating when it came out, an honor they had only given to 15 albums at the time of release. The LP was a work of love. It was produced by DJ Premier, Pete Rock, Q-Tip, Large Professor, L.E.S. and Nas, in the rapper's hometown of New York City and shared a snapshot of life in the streets of NYC, set to melodic hip-hop beats. Nas shared his experience with the world in a raw yet refreshing way. As he raps on "N.Y. State of Mind," "Life is parallel to hell but I must maintain."

Source's Shortie captured the anticipation and excitement around the album in her 1994 review. "After peeping his soul on 'Live at the BBQ,' 'Back to the Grill,' and the official bomb, 'Halftime,' street dwellers and industry folks alike were predicting Nas' first album to be monumental," she shared. "I must maintain that this is one of the best hip-hop albums I have ever heard. Musically, when Nas hooked up with four of hip-hop's purest producers, it seems like all of the parties involved took their game to a higher level of expression," she furthered. Those would be echoed by countless fans and critics at the time and retrospectively.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/hxce_qvhi5I" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

As the rapper said himself when explaining the meaning of the title, the album most definitely is "supreme ill" or "as ill as it gets." The album debuted and peaked at No. 12 on the Billboard 200, and although its singles surprisingly did not chart, the songs, including "The World Is Yours" and "One Love," featuring co-producer Q-Tip, have had a long-lasting impact and staying power through speakers and in the hip-hop arsenal of records. These tracks, and the album as a whole, are often credited as creating the blueprint for the new East Coast hip-hop sound that thrived following its release.

<iframe allow="autoplay *; encrypted-media *;" frameborder="0" height="450" style="width:100%;max-width:660px;overflow:hidden;background:transparent;" sandbox="allow-forms allow-popups allow-same-origin allow-scripts allow-storage-access-by-user-activation allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation" src="https://embed.music.apple.com/us/album/illmatic/662324135"></iframe>

Photo: Oye Diran

interview

Meet Derrick Hodge, The Composer Orchestrating Hip-Hop's Symphony

From Nas' 'Illmatic' to modern hip-hop symphonies, Derrick Hodge seamlessly bridges the worlds of classical and hip-hop music, bringing orchestral elegance to iconic rap anthems.

Over the last 50 years, hip-hop culture has shown it can catalyze trends in fashion and music across numerous styles and genres, from streetwear to classical music. On June 30, Nas took his place at Red Rocks Amphitheater in a full tuxedo, blending the worlds of hip-hop and Black Tie once again, with the help of Derrick Hodge.

On this warm summer eve in Morrison, Colorado, Nas performed his opus, Illmatic, with Hodge conducting the Colorado Symphony Orchestra. The show marked a belated 30-year celebration of the album, originally released on April 19, 1994.

As Nas delivered his icy rhymes on classics like "N.Y. State of Mind," "Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)," and "Halftime," the orchestra held down the beat with a wave of Hodge's baton. The winds, strings, and percussion seamlessly transitioned from underscoring Nas's lyrics with sweeping harmonic layers to leading melodic orchestral flourishes and interludes. For the album's final track, "Ain't Hard to Tell," the orchestra expanded on Michael Jackson's "Human Nature," expertly sampled originally by producer Large Professor.

Derrick Hodge is a pivotal figure in modern music. His career spans writing and performing the famous bassline on Common's "Be," composing for Spike Lee's HBO documentary "When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts," and his own solo career that includes his latest experimental jazz album, COLOR OF NOIZE. Hodge also made history by bringing hip-hop to the Kennedy Center with orchestra accompaniments for Illmatic to celebrate the album's 20th anniversary in 2014.

"That was the first time hip-hop was accepted in those walls," Hodge says sitting backstage at Red Rocks. It was also the first time Hodge composed orchestral accompaniments to a hip-hop album.

Since then, Hodge has composed symphonic works for other rappers including Jeezy and Common, and is set to deliver a symphonic rendition of Anderson .Paak's 2016 album, Malibu, at the Hollywood Bowl in September.

Hodge's passion for orchestral composition began when he was very young. He played upright bass by age seven and continued to practice classical composition in his spare moments while touring as a bassist with Terence Blanchard and Robert Glasper. On planes. In dressing rooms. In the van to and from the gig.

"It started as a dream. I didn't know how it was going to be realized. My only way to pursue that dream was just to do it without an opportunity in sight," Hodge says. "Who would've known that all that time people were watching? Friends were watching and word-of-mouth."

His dedication and word-of-mouth reputation eventually led Nas to entrust him with the orchestral arrangements for Illmatic. He asked Hodge and another arranger, Tim Davies, to write for the performance at the Kennedy Center.

"[Nas] didn't know much about me at all," Hodge says. "For him to trust how I was going to paint that story for an album that is very important to him and important to the culture, I have not taken that for granted."

Read more: How 'Illmatic' Defined East Coast Rap: Nas’ Landmark Debut Turns 30

Those parts Hodge wrote for the Kennedy Center are the same parts he conducted at Red Rocks. Over a decade later, he channels the same drive and hunger he had when he was practicing his compositions between gigs. "I hope that I never let go of that. I feel like these opportunities keep coming because I'm approaching each one with that conviction. Like this could be my last."

Before this latest performance, GRAMMY.com spoke with Hodge about bridging the worlds of classical and hip-hop, influencing the next generation of classical musicians, and how his experience as a bassist helps him lead an orchestra.

Throughout history, orchestral music has been celebrated by the highest echelons of society, whereas hip-hop has often been shunned by that echelon. What is it like for you to bring those two worlds together?

I love it. I've embraced the opportunity since day one. I was a young man showing up with Timberlands on and cornrows in my hair, and I knew the tendency to act and move in a certain perception was there. I knew then I have to represent hope in everything I do. I choose to this day to walk with a certain pair of blinders on because I feel like it's necessary. Because of that I never worry about how the classical world perceives me.

Oftentimes I'll stand before them and I know there may be questions but the love I show them, what I demand of them, and how I show appreciation when they take the music seriously…almost every situation has led to lifelong friendships.

I believe that's been part of my purpose. It's not even been to change minds or change perceptions. In serving the moment, even when people have preconceptions, they're in front of me playing music I wrote. How do I serve them best? How do I bring out the best in them just like I'm trying to bring out the best in the storyline of a hip-hop artist that may not relate to their story at all? The answer is just to be selfless. That's eliminated the distraction of trying to convince minds.

With that unifying principle, would you consider conducting the orchestra the same thing as playing bass with Robert Glasper?

The way I try to be selfless and serve the moment, it's no different. Maybe the skillset that's required. For example, conducting or working within a framework of composed music requires a certain way of making sure everybody's on the same page so we can get through these things on time and keep going. But I serve that moment no differently than when myself and Robert Glasper, Chris Dave, Casey Benjamin RIP, are creating a song in the moment.

I actually don't even think about how one thing is affecting the other. I will say the beauty of the bass and the bassists that have influenced me — from Ron Carter to the great Marcus Miller, Victor Wooten — is the way they can stand out while never abandoning the emotion of the moment. Remembering what is perceived as the role of the bass and how it glues things in a unique way. Harmonically and rhythmically. Being aware of the responsibility of being aware of everything.

I think that's one thing that's carried over to orchestrating and thinking about balances and how to convey emotion. I think some things are innate with bassists. We're always navigating through harmony and having a conversation through a lens of placement with drums. Placement with the diction if they're singers or rappers. There are a lot of decisions bass players are making in the moment that we don't even think about. It's just secondhand. But it's how are we serving what's necessary to make the conversation unified. I think that's one thing that's served me well in composition.

What's one song you're particularly excited to dive into for the Anderson .Paak arrangements?

So I'm intentionally not thinking in that way because we decided to treat it like a movie. Start to finish no matter what. With that in mind, I'm trying to approach it as if the whole thing is an arcing story because I didn't realize the succession of how he placed that record was really important to him.

**Hip-hop is often a very minimalist genre while an orchestra is frequently the opposite with dozens of instruments. How do you maintain that minimalist feel when writing orchestra parts for hip-hop albums like Illmatic?**

I'm so glad you asked that because that was the biggest overarching thing I had to deal with on the first one. With Nas. Because Illmatic, people love that as it is. Every little thing. It wasn't just the production. Nas's diction in between it, how he wrote it, how he told the story, and the pace he spoke through it. That's what made it. So the biggest thing is how do I honor that but also try to tell the story that honors the narrative of symphonic works? [The orchestra is] fully involved. How do I do things in a way where they are engaged without forcing them?

Illmatic was a part of my soundtrack. So I started with the song that meant the most to me at that time: "The World is Yours." That was the first piece I finished, and I emailed Pete Rock and asked "How is this feeling to you?" If the spirit of the song is speaking to him then I feel like this is something I can give to the people no matter how I feel about it. And he gave the thumbs up.

So instead of overly trying to prove a point within the flow of the lyrics, how do we pick those moments when the orchestra is exposed? Let them be fully exposed. Let them tell a story leading into that. Make what they do best marry well into what Nas and the spirit of hip-hop and hip-hop sampling do best. And then let there be a dance in between.

That first [Illmatic] show was a great experiment for me. I try to carve out moments whenever I can. Let me figure out what's a story that can combine this moment with this moment. That's become the beauty. Especially within the rap genre. To let something new that they're not familiar with lead into this story.

*Derrick Hodge conducts the Colorado Symphony Orchestra at Red Rocks* | Amanda Tipton

The orchestra is just as excited to play it as Nas is to have them behind him.

And that reflects my story. I try to dedicate more time to thinking about that, and that normally ends up reciprocated back in the way they're phrasing. In the way they're honoring the bowings. In the way they're honoring the breaths that I wrote in for them. They start to honor that in a way because they know we're coming to try and have a conversation with these orchestras. That's one thing I try to make sure no matter what. It's a conversation and that goes back to the moment as well.

I've seen other composers put an orchestral touch on hip-hop in recent years. For example, Miguel Atwood-Ferguson wrote orchestral parts to celebrate Biggie's 50th birthday. Would you say integrating an orchestra into hip-hop is becoming more popular?

It has become popular, especially in terms of catching the eyes of a lot of the different symphonies that might not have opened up their doors to that as frequently in the past. These opportunities — I appreciate the love shown where my name is mentioned in terms of the inception of things. But I approach it with a lot of gratitude because others were doing it and were willing to honor the music the same. There are many that wish they had that opportunity so I try to represent them.

With these more modern applications of orchestral music, I feel like there will be an explosion of talent within the classical realm in the next few years. Kids will think it's cool to play classical again.

The possibility of that just brings joy to me. Not just because it's a spark, but hopefully the feeling in the music they relate to. Hopefully there is something in it, aside from seeing it done, that feels that it relates to their story. I have confidence if I'm true to myself, hopefully, each time in the music it's going to feel like it's something relevant to the people. The more I can help foster platforms where people are free to be themselves, and where they can honor the music—I hope that mentality becomes infectious.

More Rap News

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

On Rakim's 'G.O.D's Network (REB7RTH)' The MC Turned Producer Continues His Legacy With An All-Star Cast

5 Ways Mac Dre's Final Living Albums Shaped Bay Area Rap

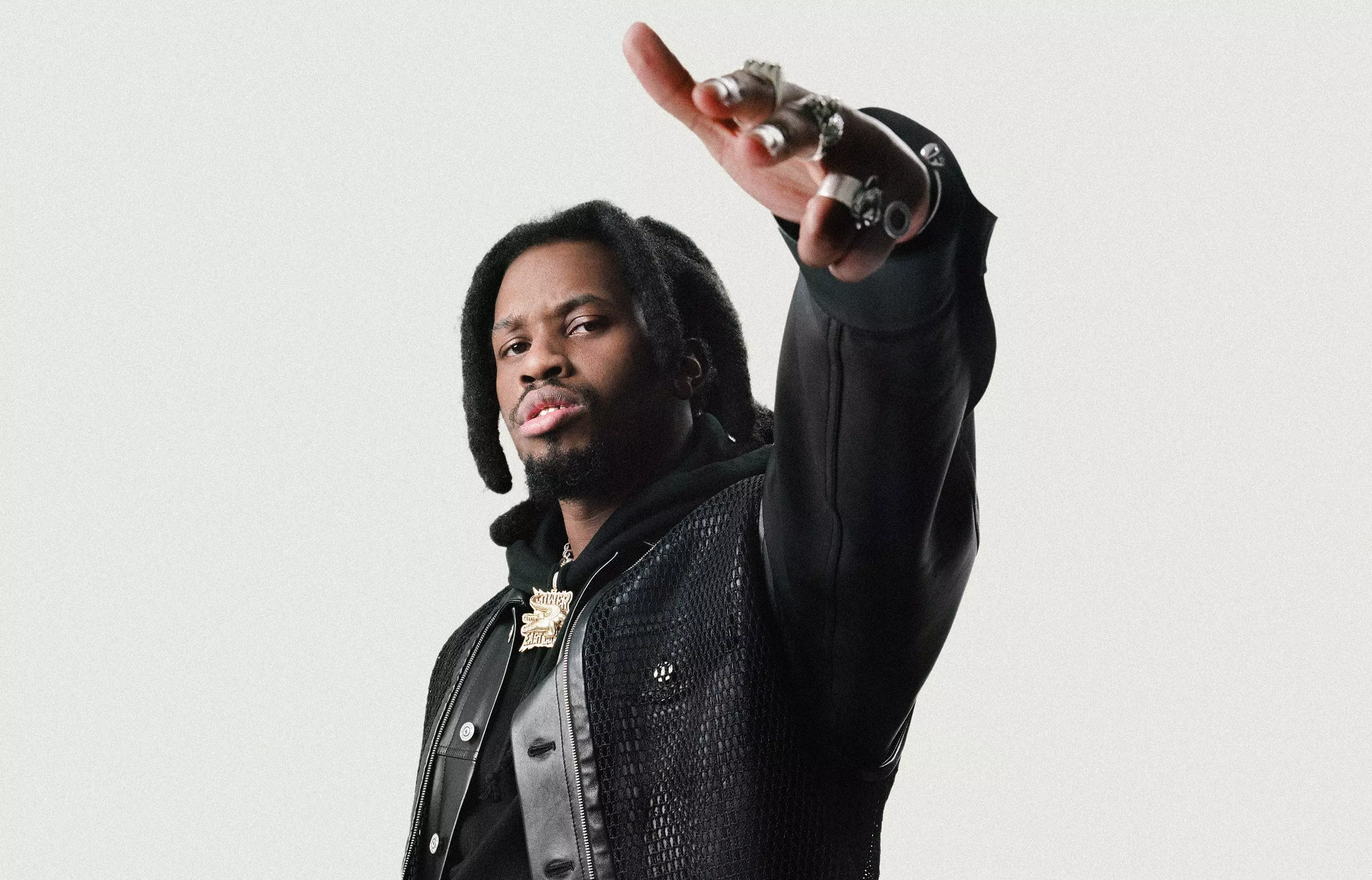

Denzel Curry Returns To The Mischievous South: "I've Been Trying To Do This For The Longest"

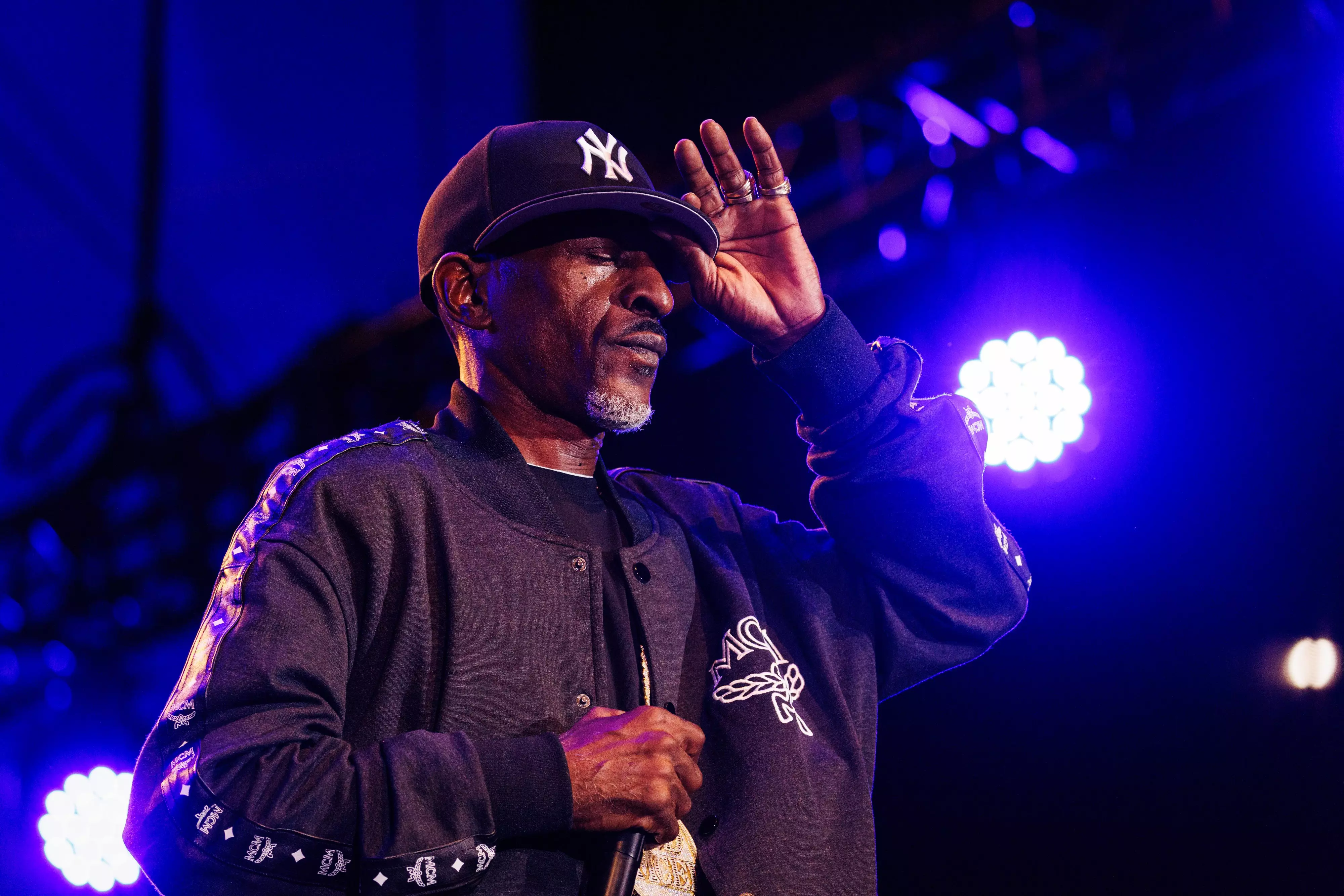

Photo: Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Live Nation Urban

list

9 Lively Sets From The 2024 Roots Picnic: Jill Scott, Lil Wayne, Nas, Sexyy Red, & More

From hit-filled sets by The-Dream and Babyface to a star-studded tribute to New Orleans, the 2024 iteration of the Roots Picnic was action-packed. Check out a round-up of some of the most exciting sets here.

As June kicked off over the weekend, The Roots notched another glorious celebration at West Philadelphia's Fairmount Park with the 16th annual Roots Picnic. This year's festival featured even more activations, food vendors, attendees, and lively performances.

On Saturday, June 1, the action was established from the onset. October London and Marsha Ambrosius enlivened the soul of R&B lovers, while Method Man and Redman brought out surprise guests like Chi-town spitter Common and A$AP Ferg for a showstopping outing.

Elsewhere, rappers Smino and Sexyy Red flashed their St. Louis roots and incited fans to twerk through the aisles of the TD Pavilion. And Philly-born Jill Scott's sultry vocals made for a memorable homecoming performance during her headlining set.

The momentum carried over to day two on Sunday, June 2, with rising stars like Shaboozey and N3WYRKLA showing the Roots Picnic crowd why their names have garnered buzz. Later in the day, rapper Wale brought his signature D.C. swag to the Presser Stage. And while Gunna's performance was shorter than planned, it still lit the fire of younger festgoers.

Closing out the weekend was a savory tribute to New Orleans courtesy of The Roots themselves, which also starred Lil Wayne, acclaimed R&B vocalists, an illustrious jazz band, and some beloved NoLa natives.

Read on for some of the most captivating moments and exciting sets from the 2024 Roots Picnic.

The-Dream Serenaded On The Main Stage

The-Dream | Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Live Nation Urban

After years away from the bright lights of solo stardom, The-Dream made a triumphant return to the festival stage on Saturday. The GRAMMY-winning songwriter and producer played his timeless R&B hits like "Falsetto" and "Shawty Is Da S––," reminding fans of his mesmerizing voice and renowned penmanship.

His vocals melted into the sunset overlooking Fairmount Park Saturday evening. And even in moments of audio malfunctions, he was able to conjure the greatness he's displayed as a solo act. Although, it may have looked easier than it was for the Atlanta-born musician: "Oh, y'all testing me," he said jokingly.

The-Dream slowed it down with the moodier Love vs. Money album cut "Fancy," then dug into the pop-funk jam "Fast Car" and the bouncy "Walkin' On The Moon." He takes fans on a ride through his past sexual exploits on the classic "I Luv Your Girl," and closes on a fiery note with the "Rockin' That S—." While even he acknowledged that his set wasn't perfect, it left fans hoping to see more from the artist soon.

Smino Rocked Out With His Philly "Kousins"

Smino | Shaun Llewellyn

Despite somewhat of a "niche" or cult-like following, Smino galvanized music lovers from all corners to the Presser Stage. The St. Louis-bred neo-soul rapper played silky jams like "No L's" and "Pro Freak" from 2022's Luv 4 Rent, then dove into the sultry records from his earlier projects.

"Klink" set the tone for the amplified showcase, with fans dancing in their seats and through the aisles. His day-one fans — or "kousins," as he lovingly refers to them — joined him on songs like the head-bopping "Z4L," and crooned across the amphitheater on the impassioned "I Deserve."

Under Smino's musical guidance, the crowd followed without a hitch anywhere in the performance. It further proved how magnetic the "Netflix & Dusse" artist is live, and how extensive his reach has become since his 2017 debut, blkswn.

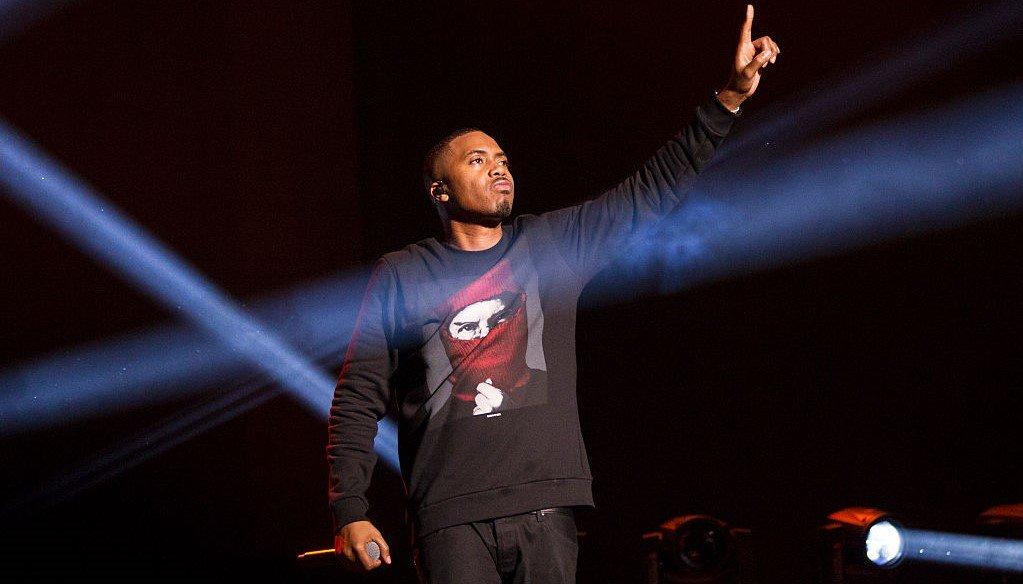

Nas Took Fans Down Memory Lane

Nas | Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Live Nation Urban

The New York and Philadelphia connection was undeniable Saturday, as legendary Queensbridge MC Nas forged the two distinctive cities for a performance that harnessed an "Illadelph State of Mind."

The "I Gave You Power" rapper played his first show in Philadelphia as a teenager, when he only had one verse under his belt: Main Source's 1991 song "Live at the BBQ." Back then, Nas admitted to underplaying the city's influence, but he knew then what he knows now — "I had to step my s— up." And he did.

The rapper played iconic songs like "Life's a B–" and "Represent" from his landmark debut Illmatic, which celebrated 30 years back in April. He even brought out Wu-Tang Clan's Ghostface Killah to add to the lyrical onslaught, and played records like "Oochie Wally" and "You Owe Me" to enliven his female fans.

Sexyy Red Incited A Twerk Fest

Sexyy Red | Frankie Vergara

Hot-ticket rapper Sexyy Red arrived on the Presser Stage with a message: "Make America Sexyy Again." And as soon as Madam Sexyy arrived, she ignited a riot throughout the TD Pavilion aisles. Twerkers clung onto friends and grasped nearby railings to dance to strip club joints like "Bow Bow Bow (F My Baby Dad)" and "Hood Rats."

Red matched the energy and BPM-attuned twerks from her fans, which only intensified as her lyrics grew more explicit. Sexyy encouraged all of the antics with a middle finger to the sky, her tongue out, and her daring lyrics filling the air. Songs like "SkeeYee" and "Pound Town" added to the nonstop action, leaving fans in a hot sweat — and with their inner sexyy fully unlocked.

Jill Scott Delivered Some Homegrown Magic

Jill Scott (left) and Tierra Whack | Marcus McDonald

To close out night one, the Roots Picnic crowd congregated at the Park Stage for a glimpse of Philadelphia's native child, Jill Scott. The famed soulstress swooned with her fiery voice and neo-soul classics like "A Long Walk" and "The Way." Fans swayed their hips and sang to the night sky as Scott sprinkled her musical magic.

Scott, wrapped up in warm, sapphire-toned garments, was welcomed to the stage by Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle L. Parker. The newly elected official rallied the audience for a "Philly nostalgic" evening, and the GRAMMY-winning icon delivered a soaring performance that mirrored her vocal hero, Kathleen Battle. "Philadelphia, you have all of my love," Scott gushed. "I'm meant to be here tonight at this Roots Picnic."

"Jilly from Philly" invited some of the city's finest MCs to the stage for the jam session. Black Thought rapped along her side for The Roots' "You Got Me," and Tierra Whack stepped in for the premiere of her and Scott's unreleased rap song, a booming ode to North Philly.

Fantasia & Tasha Cobbs Leonard Brought Electrifying Energy

Fantasia | Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Live Nation Urban

Led by the musical maestro Adam Blackstone, singers Tasha Cobbs Leonard and Fantasia set the warmness of Sunday service and their Southern flare with a "Legacy Experience." And as the title of the performance suggests, their fiery passion was a thread of musical mastery.

As fans danced across the lawn, it was just as much a moment of worship as it was a soulful jam — and only the dynamic voices of the two Southern acts could do the job. "Aren't y'all glad I took y'all there this Sunday," Blackstone said.

The sanctity of Tasha Cobbs Leonard's vocals was most potent on "Put A Praise On It," and Fantasia's power brought the house down even further with classics like "Free Yourself" and "When I See U."

"I wasn't supposed to come up here and cut. I'm trying to be cute," Fantasia joked after removing her shoes on stage. The North Carolina native's lips quivered and her hands shook in excitement, as she continued to uplift the audience — fittingly closing with a roaring rendition of Tina Turner's "Proud Mary."

Babyface Reminded Of His Icon Status

Babyface | Marcus McDonald

There are few artists who could dedicate a full set to their own records, or the hits they've penned for other musicians. And if you don't know how special that is, Babyface won't hesitate to remind you. "I wrote this back in 1987," he said before singing the Whispers' "Rock Steady."

Throughout the legendary R&B singer's 45-minute set, he switched between his timeless records like "Every Time I Close My Eyes" and "Keeps on Fallin'," and those shared by the very artists he's inspired — among them, Bobby Brown's "Don't Be Cruel" and "Every Little Step,"

Fans across several generations gathered to enjoy the classic jams. There was a look of awe in their eyes, as they marveled at the work and memories Babyface has created over more than four decades.

André 3000 Offered Layers Of Creativity

André 3000 | Marcus McDonald

Speculation over what André 3000 would bring to his Sunday night set was the buzz all weekend. Fans weren't sure if they were going to hear the "old André," or the one blowing grandiose tones from a flute on his solo debut, 2023's New Blue Sun.

The former Outkast musician went for the latter, and while some fans were dismayed by the lack of bars, hundreds stayed for the highly rhythmic set. "Welcome to New Blue Sun live," André said. The majestic chimes and flowy notes of his performance reflect a new creative outlook, and as the performance went on, there was a cloud of coolness that loomed over the amphitheater.

His artistic approach is new to many fans, but he never stopped showcasing the personality they have grown to love. After delivering a message in an indistinguishable language, he panned to the crowd with a look of deep thought and said, "I just want y'all to know, I made all that s— up." It's the kind of humor fans have admired from him for decades, and moments like those are one of many reasons they stayed to watch the nuances of the MC's set.

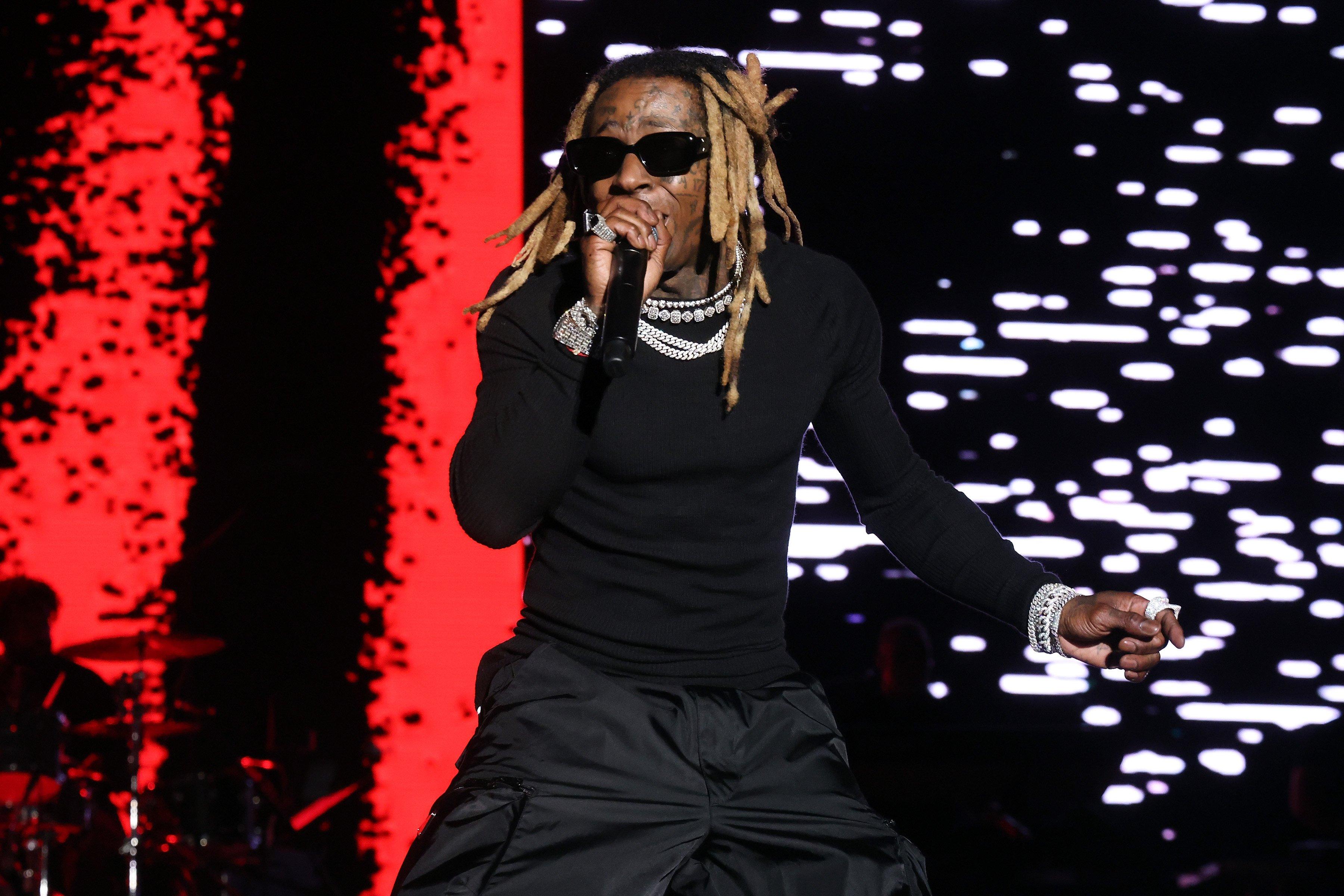

Lil Wayne & The Roots Gave New Orleans Its Magnolias

Trombone Shorty (left) and Black Thought | Taylor Hill/Getty Images for Live Nation Urban

The sound of jazz trombones and the gleam of Mardi Gras colors transported West Philly to the bustling streets of New Orleans for the closing set of Roots Picnic 2024. The ode to the Big Easy featured natives like Lloyd, PJ Morton and the marvelous Trombone Shorty, all of whom helped deliver a celebratory tribute that matched the city's vibrance.

Lloyd floated to the stage singing The Roots' "Break You Off," and delved into his own catalog with "Get It Shawty" and "You." Morton soon followed with a soulful run of his R&B records, including "The Sweetest Thing" and "Please Be Good."

With anticipation on full tilt, Black Thought welcomed the festival closer to the stage with a message: "It's only right if Philly pays homage to New Orleans that we bring out Lil Wayne." And right on cue, Wayne drew a wave of cheers as he began "Mr. Carter."

Wayne strung together his biggest Billboard-charting and street hits, including "Uproar," "Hustler's Muzik" and "Fireman." The performance was a rousing cap-off to the weekend — and it clearly meant a lot to the rapper to rep his city in such grand fashion.

"This is a dream come true," Wayne said. "It's a motherf–ing honor."

11 New Music Festivals To Attend In 2024: No Values, We Belong Here & More

Photo: Kimberly White/Getty Images for Hennessy

feature

How 'Illmatic' Defined East Coast Rap: Nas’ Landmark Debut Turns 30

Three decades after Nas released his debut album, 'Illmatic' remains the holy grail of East Coast rap. From poetic, pulled-from-life lyrics to its all-star cast of producers, learn how 'Illmatic' reignited New York’s rap supremacy in the mid-1990s.

After shaking up the rap game with a breakout verse on the Main Source’s "Live at the Barbeque," a 17-year-old, chip-toothed MC named Nasir "Nas" Jones was crowned a prophet. His silk-smooth delivery and poetic rhymes on the 1991 jam were reminiscent of hip-hop greats like Kool G Rap and Rakim.

The verse — which included the line "Verbal assassin, my architect pleases. When I was 12, I went to hell for snuffin’ Jesus" — bestowed heavy expectations on the Queens native. While Nas was discovered by Main Source’s Large Professor, the young MC was soon drawing the attention of music label heads who wanted to ink a deal with the emerging artist.

"I must have rewinded that [verse] like a hundred times," former 3rd Bass rhymer MC Search said in the 2014 documentary Nas: Time Is Illmatic. "This Main Source album is brilliant, but who’s that kid? It almost felt like within a week, everybody wanted to know who that guy was."

Through Nas’ connection with Search, he found a home at Sony Music’s Columbia, and notched another memorable verse on 1992’s "Back To The Grill." But on April 19, 1994, Nas delivered the greatest debut in rap history: Illmatic.

Thirty years later,. Nas’ masterful stroke of poeticism and the gritty boom-bap loops on songs "It Ain’t Hard to Tell," "The World Is Yours," and "N.Y. State of Mind" still resonate. The album also revived the fleeting dominance of NY rap, and unexpectedly inspired other rappers to release albums with their baby pictures on the cover. Its influential power, and the amalgam of musical forces that threaded the album together, made Illmatic one of the definitive East Coast rap albums of the golden age. Few hip-hop albums have been as widely heralded for as long as Illmatic.

The landmark project chronicled Nas’ life growing up in the Queensbridge housing projects while helping restore the influence of East Coast rap on a now bicoastal scene. By '94, the West coast was taking the reins for the first time in the genre’s history. In Southern California, Dr. Dre’s The Chronic and Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle popularized G-funk, which soon permeated the airwaves and topped the Billboard charts. Alternative West Coast acts like Oakland's Souls of Mischief and South Central's the Pharcyde were also establishing firm ground.

The mecca of hip-hop was no longer atop the leaderboard, but with his first full-length release, Nas was inspired to reclaim New York’s dominance and rekindle Queenbridge’s spark from the late 1980s. "I had to represent," Nas said in a 2019 interview with Drink Champs. "The pressure was on the borough and my project. And just getting into the game, you had to have something to say, so I definitely had to push the pen hard because, if not, it would’ve never [flown]."

Queensbrige is home to the largest housing project in the U.S., and birthed pioneers like MC Shan, Marley Marl, and the fearsome Juice Crew. They fell to South Bronx’s KRS-One and the Boogie Down Productions collective in the infamous "Bridge Wars," which left the Long Island City section seeking a new heir. And Nas, inspired by the lyrical warfare, took up the mantle.

Nas and Large Professor hired legendary producers DJ Premier, Pete Rock, Q-Tip, L.E.S, and others to work on Illmatic. They set the sonic lines, and Nas filled the gaps in spoken word form.

Read more: A Guide To New York Hip-Hop: Unpacking The Sound Of Rap's Birthplace From The Bronx To Staten Island

From their first studio session together, Q-Tip knew Nas’ skills were unlike any other he’d seen before. "You automatically knew," the A Tribe Called Quest legend (and fellow son of Queens) said in an interview with Red Bull Music Academy. "When Large Professor first played him for me, I heard him on the Live at the Barbeque,’ but then Large [Professor] played me his s— and I was like, ‘This dude is crazy, you know what I’m saying?’ I knew it was going to be the impact it was."

The project was a storybook of lived experiences, even down to the iconic album cover. Nas peeled back the layers of street violence, mass incarceration, and generations of disenfranchisement throughout the 10-track LP. "Memory Lane (Sitin’ in da Park)" and "One Time 4 Your Mind" transported listeners to the hardened corners of Queens, where the air was filled with marijuana smoke and the distant whispers from street hustlers.

On the Tri-State anthem "N.Y. State of Mind," Nas’ creative equilibrium was at full balance. In Time Is Illmatic, Nas said the song’s early placement on the LP was intentional. He knew it would "bring [listeners] to hell and back."

"One Love" captured the pain of incarceration, with Nas’ descriptive story of distrust and heartbreak overlaying a chillingly euphoric beat. The AZ-assisted "Life’s a Bitch" is a celebratory toast to survival, and "It Ain’t Hard to Tell" is a masterful showcase of braggadocious rap.

The topics that I talk about were topics that were around before ‘Illmatic’; streets, social economic status, people’s struggles," Nas told Clash magazine. "I just told it crazy real, and it just talks about how to live in the circumstances and goes beyond, dreaming at the same time. Never just stay in the situation that you’re in."

The album was showered with praise upon release, with the Source blessing the album with a highly-coveted five-mic review. The rare score was administered by former Hot 97 radio personality and then-Source intern Minya Oh, who declared it one of the best albums she had ever heard. "Lyrically, the whole s— is on point. No cliched metaphors, no gimmicks. Never too abstract, never superficial."

The rave responses didn’t initially translate to album sales. Ilmatic debuted at No. 12 on the Billboard 200, only selling around 60,000 copies in its first week. The low sales were attributed to pre-Internet leaks, with renderings of Illmatic in circulation up to a year before its official release date, according to Clash. The standout singles also failed to scratch the charts.

Illmatic eventually sold more than two million copies, but the underwhelming start surprised DJ Premier. "We knew it was going to be that big of a deal, that’s why I never understood why it didn’t go like super platinum quick," Premier said to Mass Appeal. "I thought it was going to be super fast and it didn’t. I thought this one was going to be a big platinum album."

But three decades after its release, Illmatic influenced several generations of rap stars and retained its status as one of the best albums in rap history. In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked the album no. 44 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Large Professor, who continued to work with Nas on later albums, said Illmatic is a pillar of hip-hop history. "It’s one of the roots of the tree of hip-hop because a lot of styles came from that. A lot of rhyme styles. He got people thinking outside of the norm," the producer said to HipHopDX in 2014. The stuff that he was rhyming was just crazy, man. But, it’s definitely one of the roots that hold the tree of hip-hop up strong."

Nas’ contributions has placed him among the best MCs of all time, and justifiably so. He’s continued to deliver No. 1 albums and hit singles throughout the decades, and scored his first GRAMMY Award for Best Rap Album in 2021 after more than a dozen nominations.

While Nas no longer listens to Illmatic and avoids celebrating the project, telling Haute Living that it’s "corny" to continue championing one album when he’s done so many others. But fans’ continued admiration for the album proves that his early goals were met. The reputation of East Coast rap and Queensbridge was restored, and Nas’ legacy will forever be immortalized. Mission accomplished, Esco.

'Run-DMC' At 40: The Debut Album That Paved The Way For Hip-Hop's Future

Photo: Clarence Davis/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

feature

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

With debuts from major artists including Biggie and Outkast, to the apex of boom bap, the dominance of multi-producer albums, and the arrival of the South as an epicenter of hip-hop, 1994 was one of the most important years in the culture's history.

While significant attention was devoted to the celebration of hip-hop in 2023 — an acknowledgement of what is widely acknowledged as its 50th anniversary — another important anniversary in hip-hop is happening this year as well. Specifically, it’s been 30 years since 1994, when a new generation entered the music industry and set the genre on a course that in many ways continues until today.

There are many ways to look at 1994: lists of great albums (here’s a top 50 to get you started); a look back at what fans and tastemakers were actually listening to at the time; the best overlooked obscurities. But the best way to really understand why a single 365 three decades ago had such an impact is to narrow our focus to look at the important debut albums released that year.

An artist’s or group’s debut is their entry into the wider musical conversation, their first full statement about who they are and where in the landscape they see themselves. The debuts released in 1994 — which include the Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die, Nas' Illmatic and Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik from Outkast — were notable not only in their own right, but because of the insight they give us into wider trends in rap.

Read on for some of the ways that 1994's debut records demonstrated what was happening in rap at the time, and showed us the way forward.

Hip-Hop Became More Than Just An East & West Coast Thing

The debut albums that moved rap music in 1994 were geographically varied, which was important for a music scene that was still, from a national perspective, largely tied to the media centers at the coasts. Yes, there were New York artists (Biggie and Nas most notably, as well as O.C., Jeru the Damaja, the Beatnuts, and Keith Murray). The West Coast G-funk domination, which began in late 1992 with Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, continued with Dre’s step brother Warren G.

But the huge number of important debuts from other places around the country in 1994 showed that rap music had developed mature scenes in multiple cities — scenes that fans from around the country were starting to pay significant attention to.

To begin with, there was Houston. The Geto Boys were arguably the first artists from the city to gain national attention (and controversy) several years prior. By 1994, the city’s scene had expanded enough to allow a variety of notable debuts, of wildly different styles, to make their way into the marketplace.

Read more: A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

The Rap-A-Lot label that first brought the Geto Boys to the world’s attention branched out with Big Mike’s Somethin’ Serious and the Odd Squad’s Fadanuf Fa Erybody!! Both had bluesy, soulful sounds that were quickly becoming the label’s trademark — in no small part due to their main producers, N.O. Joe and Mike Dean. In addition, an entirely separate style centered around the slowed-down mixes of DJ Screw began to expand outside of the South Side with the debut release by Screwed Up Click member E.S.G.

There were also notable debut albums by artists and groups from Cleveland (Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Creepin on ah Come Up), Oakland (Saafir and Casual), and of course Atlanta — more about that last one later.

1994 Saw The Pinnacle Of Boom-Bap

Popularized by KRS-One’s 1993 album Return of the Boom Bap, the term "boom bap" started as an onomatopoeic way of referring to the sound of a standard rap drum pattern — the "boom" of a kick drum on the downbeat, followed by the "bap" of a snare on the backbeat.

The style that would grow to be associated with that name (though it was not much-used at the time) was at its apex in 1994. A handful of primarily East Coast producers and groups were beginning a new sonic conversation, using innovations like filtered bass lines while competing to see who could flip the now standard sample sources in ever-more creative ways.

Most of the producers at the height of this style — DJ Premier, Buckwild, RZA, Large Professor, Pete Rock and the Beatnuts, to name a few — worked on notable debuts that year. Premier produced all of Jeru the Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East. Buckwild helmed nearly the entirety of O.C.’s debut Word…Life. RZA was responsible for Method Man’s Tical. The Beatnuts took care of their own full-length Street Level. Easy Mo Bee and Premier both played a part in Biggie’s Ready to Die. And then there was Illmatic, which featured a veritable who’s who of production elites: Premier, L.E.S., Large Professor, Pete Rock, and Q-Tip.

The work the producers did on these records was some of the best of their respective careers. Even now, putting on tracks like O.C.’s "Time’s Up" (Buckwild), Jeru’s "Come Clean" (Premier), Meth’s "Bring the Pain" (RZA), Biggie’s "The What" (Easy Mo Bee), or Nas’ "The World Is Yours" (Pete Rock) will get heads nodding.

Major Releases Balanced Street Sounds & Commercial Appeal

"Rap is not pop/If you call it that, then stop," spit Q-Tip on 1991’s "Check the Rhime." Two years later, De La Soul were adamant that "It might blow up, but it won’t go pop." In 1994, the division between rap and pop — under attack at least since Biz Markie made something for the radio back in the ‘80s — began to collapse entirely thanks to the team of the Notorious B.I.G. and his label head and producer Sean "Puffy" Combs.

Biggie was the hardcore rhymer who wanted to impress his peers while spitting about "Party & Bulls—." Puff was the businessman who wanted his artist to sell millions and be on the radio. The result of their yin-and-yang was Ready to Die, an album that perfectly balanced these ambitions.

This template — hardcore songs like "Machine Gun Funk" for the die-hards, sing-a-longs like "Juicy" for the newly curious — is one that Big’s good friend Jay-Z would employ while climbing to his current iconic status.

Solo Stars Broke Out Of Crews

One major thing that happened in 1994 is that new artists were created not out of whole cloth, but out of existing rap crews. Warren G exploded into stardom with his debut Regulate… G Funk Era. He came out of the Death Row Records axis — he was Dre’s stepbrother, and had been in a group with a pre-fame Snoop Dogg. Across the country, Method Man sprang out of the Wu-Tang collective and within a year had his own hit single with "I’ll Be There For You/You’re All I Need To Get By."

Anyone who listened to the Odd Squad’s album could tell that there was a group member bound for solo success: Devin the Dude. Keith Murray popped out of the Def Squad. Casual came out of the Bay Area’s Hieroglyphics.

Read more: A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

This would be the model for years to come: Create a group of artists and attempt, one by one, to break them out as stars. You could see it in Roc-a-fella, Ruff Ryders, and countless other crews towards the end of the ‘90s and the beginning of the new millennium.

Multi-Producer Albums Began To Dominate

Illmatic was not the first rap album to feature multiple prominent producers. However, it quickly became the most influential. The album’s near-universal critical acclaim — it earned a perfect five-mic score in The Source — meant that its strategy of gathering all of the top production talent together for one album would quickly become the standard.

Within less than a decade, the production credits on major rap albums would begin to look nearly identical: names like the Neptunes, Timbaland, Premier, Kanye West, and the Trackmasters would pop up on album after album. By the time Jay-Z said he’d get you "bling like the Neptunes sound," it became de rigueur to have a Neptunes beat on your album, and to fill out the rest of the tracklist with other big names (and perhaps a few lesser-known ones to save money).

The South Got Something To Say

If there’s one city that can safely be said to be the center of rap music for the past decade or so, it’s Atlanta. While the ATL has had rappers of note since Shy-D and Raheem the Dream, it was a group that debuted in 1994 that really set the stage for the city’s takeover.

Outkast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was the work of two young, ambitious teenagers, along with the production collective Organized Noize. The group’s first video was directed by none other than Puffy. Biggie fell so in love with the city that he toyed with moving there.

Outkast's debut album won Best New Artist and Best New Rap of the Year at the 1995 Source Awards, though the duo of André 3000 and Big Boi walked on stage to accept their award to a chorus of boos. The disrespect only pushed André to affirm the South's place on the rap map, famously telling the audience, "The South got something to say."

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

Outkast’s success meant that they kept on making innovative albums for several more years, as did other members of their Dungeon Family crew. This brought energy and attention to the city, as did the success of Jermain Dupri’s So So Def label. Then came the "snap" movement of the 2000s, and of course trap music, which had its roots in aughts-era Atlanta artists like T.I. and producers like Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp.

But in the 2010s a new artist would make Atlanta explode, and he traced his lineage straight back to the Dungeon. Future is the first cousin of Organized Noize member Rico Wade, and was part of the so-called "second generation" of the Dungeon Family back when he went by "Meathead." His world-beating success over the past decade-plus has been a cornerstone in Atlanta’s rise to the top of the rap world. Young Thug, who has cited Future as an influence, has sparked a veritable ecosystem of sound-alikes and proteges, some of whom have themselves gone on to be major artists.

Atlanta’s reign at the top of the rap world, some theorize, may finally be coming to an end, at least in part because of police pressure. But the city has had a decade-plus run as the de facto capital of rap, and that’s thanks in no small part to Outkast.

Why 1998 Was Hip-Hop's Most Mature Year: From The Rise Of The Underground To Artist Masterworks