Photo courtesy of the artist

interview

Meet The First-Time GRAMMY Nominee: Kabaka Pyramid On Embracing His Voice & The Bold Future Of Reggae

Kingston-born reggae star Kabaka Pyramid is one of a handful of artists bringing positivity back into the genre. His messages of consciousness are more powerful than ever on his third album, 'The Kalling' — and now, he’s a GRAMMY nominee because of it.

Kabaka Pyramid answers to a higher power — and his third album, fittingly titled The Kalling, is a testament to his beliefs.

The Kingston-born rapper, singer and producer is one of a handful of artists bringing positivity back into reggae, often channeling the empowered, political, and spiritual vibes of roots artists. Kabaka Pyramid is often labeled a "reggae revivalist" for this reason, but The Kalling manages to be both classic and incredibly of the moment. And while his previous albums Victory Rock and Kontraband are testaments of lyrical and genre-blending prowess, Kabaka's latest is a notable ascension.

One of five nominees for Best Reggae Album at the 65th GRAMMY Awards, The Kalling showcases Kabaka's passion for using hip-hop, soul and dancehall to iterate on the sound of conscious reggae. The record also overflows with messages of growth, contemplation of addiction, and gratitude — an antidote to some of the more crude attitudes present in Kabaka's favorite genres.

"The older I got, the more I felt responsible to represent myself in a certain way," Kabaka tells GRAMMY.com from his home in Miami. “I wanted to inspire, like how artists like Sizzla and Damian Marley inspired me. I wanted to have a similar effect, and I knew I needed to put out positive music to do that.”

Kabaka called upon his community to achieve this vision. The Kalling was produced by the reggae scion also known as Jr Gong, and features the late icon Peter Tosh in addition to Buju Banton, Jesse Royal and fellow 2023 nominee Protoje. Together, they created an album that pulls from contemporary pop, rap and '80s era reggae, with songs that are meditative ("Stand Up"), club-ready ("Energy" and "Mystik Man"), and fit for a kickback ("Mary Jane").

Ahead of the 2023 GRAMMYs, the first-time nominee spoke to GRAMMY.com about inspiring higher vibrations through music and action.

Was the GRAMMY nomination a milestone you were working towards, or one that caught you by surprise?

I was shouting, screaming, everything; a couple tears of joy. I'm probably the only person on my team and label that it kind of caught by surprise. I just always thought that the GRAMMY was just this huge thing and something that is best if I don't think about it too much, because I feel like that can lead to disappointment.

So I was just more focused on putting in the work and really representing myself with the music, and then let the awards come. But it's definitely a huge achievement for me. I wouldn't have dreamed of it when I was back in high school, but here I am now, so I have to give thanks.

It's cool to reflect on how far you've come — like, man, I'm living out my dreams from high school or dreams you didn't even know you had.

I'm 37 now, so it's been a 20-year journey since I first started to pencil down some lyrics. And most people start super early, whether they're in the church, or in the choir, or whatever it is. Or they come from a musical family, so they watch their parents do it or whatever. But for me, it wasn't that.

I always loved music, particularly hip-hop and dancehall. So I was just inspired by music, but I never thought of it as something I'd actually be doing until around 17, 18. That's when I realized that I have a talent for actually writing lyrics. And from then it was just working on my voice. A lot of self recording at home, home studios over the years, different places.

Tell me a bit about the creation of the album; what was going on in your life at that time?

The recording and writing and stuff was mostly throughout the pandemic. For the first few months, I was in Jamaica; Damien was sending me beats that he was working on from his studio in Miami. And eventually, I flew up and we started just going at it together in studio and from just jam sessions with me, him and his musicians, just coming up with ideas from scratch.

There were some conversations about what we want to do differently from the last album and what kind of song we wanted to go for, what kind of vibe. We wanted some traditional reggae, we wanted some hip-hop vibes in it, wanted to sample some classic reggae records as well as some soulful stuff. "Grateful" was a soul record that was sampled, and of course, "Mystik Man" [featuring] Peter Tosh is originally "Fade Away" by Junior Byles, a classic reggae record too.

Over two years, it just slowly but surely started to shape itself. We did "The Kalling" and Protoje and Jesse came to studio while Stephen [Marley] was recording, and they ended up dropping their verses that night. And I knew from that night that this would end up being the title track for the album. And we just kind of themed the whole album around "The Kalling." Having a higher calling, a higher purpose to the music, tying it into the teachings of Rastafari and what it means to me. It was just a beautiful process.

What do those Rastafari teachings mean to you and how are they presented on this album?

For me, Rastafari is first and foremost about knowing where you come from, seeing yourself as royalty, as kings and queens — especially for Black people who have been through slavery and coming to the West by force. So it's really a reconnection to Africa, but it applies to anybody that wants to reconnect with who they are, where they're from, and their identity.

We practice a vegan diet, ital, and man and woman relationships — being wholesome, the family unit. These are all Rastafari is and is coming from his Imperial Majesty, the emperor of Ethiopia. Ethiopia being the country that was never colonized in Africa, that really maintained their identity. That's really where Rastafari culture and expression stems from.

This record also has a lot of messaging around being aware of yourself and your addictions, and things that you're doing in your daily life that might not be so healthy. Was that something that you've been thinking about for a long time, or was it something that came to you during this production process?

As Rasta, we reason about these things all the time. It's all about looking at how we live, what's our mentality towards life. And a song like "Addiction" just came out of countless reasonings about social media, about our phones, about the radiation and our phones give off. I don't sleep with my phone near me because I wake up with headaches.

I felt like that song was so important because with the pandemic, we're taught to social distance, we're taught to stay inside and we just turned to our phones and our devices. So we're even more technologically oriented now after the pandemic than even before. It’s kind of continuing from a song I did from Kontrabrand called "Everywhere I Go."

The Kalling is much more centered in traditional reggae, though "Energy" is sort of pop and R&B, and the opening track from your last record is a pop tune. Yet you're branded as this revival reggae artist. What are your thoughts on that?

The whole revival thing came about in like 2011, 2012 when my first reggae project came out; Protoje's album was out, Chronixx [had] transitioned from being a producer/songwriter to being a recording artist, and he took Jamaica by storm. We started going to Europe with our bands, and I think that is what really cemented the whole idea of a revival, because …there was kind of a dying down of Jamaicans coming with their bands. And you had [Jamaican artists using] these backing bands that were local in Europe because it was more economical. And then a lot of artists couldn't travel anymore because of what I consider their freedom of speech being questioned and violated. So you had a lot of key artists that couldn't travel.

So because of that, when we came on the scene, it was very refreshing for people to see these young acts in their 20s coming with their bands and sacrificing where we could have made more money if we went with backing bands, or with track shows or whatever. And then not only that though, we were sampling Black Uhuru records and Sly and Robbie bass lines, and drum and bass.

If you check my song "Revival," "Here Comes Trouble" [by] Chronixx, and Protoje's "Kingston Be Wise," all of these tracks kind of brought back an '80s vibe. And then when we translate them on stage with the bands, people felt like it was a revival of the '70s and '80s.

Musically we definitely fuse a lot of the sounds. There's modern elements, there's hip-hop elements, R&B, pop elements to it too, because we're all influenced by that. We're in an era where artists kind of have more creative control with their sound — it's not like you just go to one producer that has one sound. We can call on different producers, we produce ourselves and the stuff that we are influenced by, that's what we try and recreate.

So it's partially a revival of sound but also a revival of style and performance.

Definitely.

Are there any tracks on The Kalling that you're particularly proud of?

"Mystik Man," I’m really proud of that, especially with the whole Peter Tosh family behind the song. We were able to list it officially as featuring Peter Tosh, so I have a song with one of my idols. Overall, his life, what he represents, his mission — him and Sizzla are right up there in terms of who inspire me the most. "Addiction" from a songwriting perspective, I'm really proud of that one.

I'm proud of the fact that I stuck to my roots. When I was early in my career, I couldn't sing to save my life; rapping was easier for me to do. I was working on my reggae, but I wouldn't let anybody hear those songs. So doing a song like "Kontraband pt. 2" where I'm rapping with this Jamaican accent, [or] "Mystik Man," — being able to represent that and still maintain my identity as a Jamaican [and] as a reggae artist, and to get nominated, is a great achievement for me.

I read in Dancehall Magazine that you think that the subject of a lot of Jamaican music is holding artists back. How did you try to combat that notion on The Kalling?

I think my music is naturally more wholesome. It's more readily accessible to older and the young. Maybe it can be a bit too deep for some people, but just generally speaking, I don't put a bunch of slack lyrics or derogatory lyrics to women or violence, gun violence. And that's kind of typical for Jamaican music. But I feel these younger artists are kind of pushing the limits of it. There's a lot of talk about drug use now in songs, and scamming, and all of them kind of things.

I've seen artists that are on the verge of breaking into mainstream do collaborations with other mainstream acts, but then it's just crazy curse words in the song and super derogatory lyrics. I could see somebody at a radio station like, "no, I can't playlist this because it's too difficult." Especially, being an international artist. So it's trying not to shoot ourselves in the foot by having too extreme lyrics.

How did you meet Damien Marley and what did he bring to this project?

I met him at the Bob Marley Museum, I think it was around 2013. He was shooting some videos with Nas for Distant Relatives.

The first time working with him, he sent me a riddim that he wanted to do a juggling [on]. It was originally a Wayne Marshall record, but he wanted to voice some other artists on it and Chronixx, Juliann Marley, others are on it too. I wrote the song "Well Done" on it, and we all loved the song. I was there when the song was being mixed and prepared, and that's when we really bonded, and we started to just hold our vibe, reason about music.

We played football at the field at his house. And it just felt like a brother kind of relationship from early. He's like a mentor to me; I ask him advice and everything musically. And just being with him, I learned so much about sharpening up my songwriting skills and making my lyrics more potent and more absorbable for people. From there, we just grew to the point where we had a discussion about doing two albums at minimum, and we did Kontrabrand.

He produced five of the tracks [on The Kalling], but it was all put together in his studio, [and] he executive produced the project. I wanted to give him the chance of doing a whole entire album. I felt like there was enough versatility with his production style to do it. I think he really did an excellent job. It's almost like it doesn't make sense to not do an album with him anymore.

Is there somebody who gave you props about this record that were really meaningful?

I just got a very long voicemail from Pressure Buss Pipe, who is an artist I'm really inspired by. He was telling me how much I stepped up with this album, and I'm just in the right gear now. It was really a heartfelt voice note. He's somebody that I listen to a lot, and his vocal ability inspires me, and his songwriting. I have five, six, maybe seven songs with him too.

I should say Protoje was one of the first people to call me when I got nominated. And obviously, I congratulated him as well. And even how excited Damian is [means a lot], because he's not somebody that gets excited very easy. There’s not many others who can impress you more than Damian Marley, you know what I mean?

Why did you want to feature Protoje on The Kalling and, together, what are you guys showcasing about contemporary Jamaican music?

Protoje is somebody I always want to collaborate with. He was instrumental in the start of my career; most of [my 2011 EP] Rebel Music was recorded at his home studio. About four of the beats were beats that he gave me and from other producers. Europe knew about me because Protoje kind of helped me to get my name out there. And I respect him so much.

We're all about innovation. I think Protoje's [nominated] album is super cool. The intro and "Family" and "Hills" kind of go back to his original, more hip-hop flavor. Both of us have evolved so much vocally; I love the vocal tones that he experimented with on his album. And sonically, he's always pushing the genre further and I really appreciate that about him. And similar with me, there's so much versatility around the album, but still rooted in reggae.

The two of you are nominated in a category that has a next generation artist and very established musicians. How do these nominees reflect the state of reggae?

It means a lot for everybody now because of who won last year. Big up to SOJA; I really think they put in a lot of work in this music industry, especially in the U.S. And they unified the whole U.S. reggae industry on their album; they featured all of the major acts in the U.S. and I really think it was effective.

But people see it and say, "Oh, reggae is being taken away from Jamaica" and there was a lot of backlash for that. Based on that, it's very refreshing to see an all-Jamaican lineup of artists; artists that have done so much for the industry who have been on the frontline internationally, who put out wholesome music too. It's not like any real slackness is being represented.

I would hope that this lineup of artists inspires the younger generation that you can do music without all of the negativity and it can reach the highest level. It's not that the U.S. is greater than any other nation, but it's our biggest market for the music. So to be recognized within the U.S. with this GRAMMY Award is tremendous, and everybody feels it and appreciates it.

There’s so much versatility represented: Shaggy, did a Frank Sinatra cover album. Sean Paul is modern dancehall pop. Koffee is kind of similar, but there's so much fusion going on there and she's so lyrical and so young and, just blowing up all over the place. Me and Protoje are kind of in a similar bracket. It's an interesting group.

Speaking of the next generation, who or what are you listening to these days that's giving you life? Anybody you want to big up?

There's a bunch of artists, Medicine, who actually did some songwriting on my album. Irie Soldier, Nattali Rize, Runkus, Royal Blue, Blvk H3ro, Imeru Tefari, Five Star. There's a bunch of artists out there that's doing good music, and I'm always here to support them and want to do some more production with them as well. The future is bright, for sure.

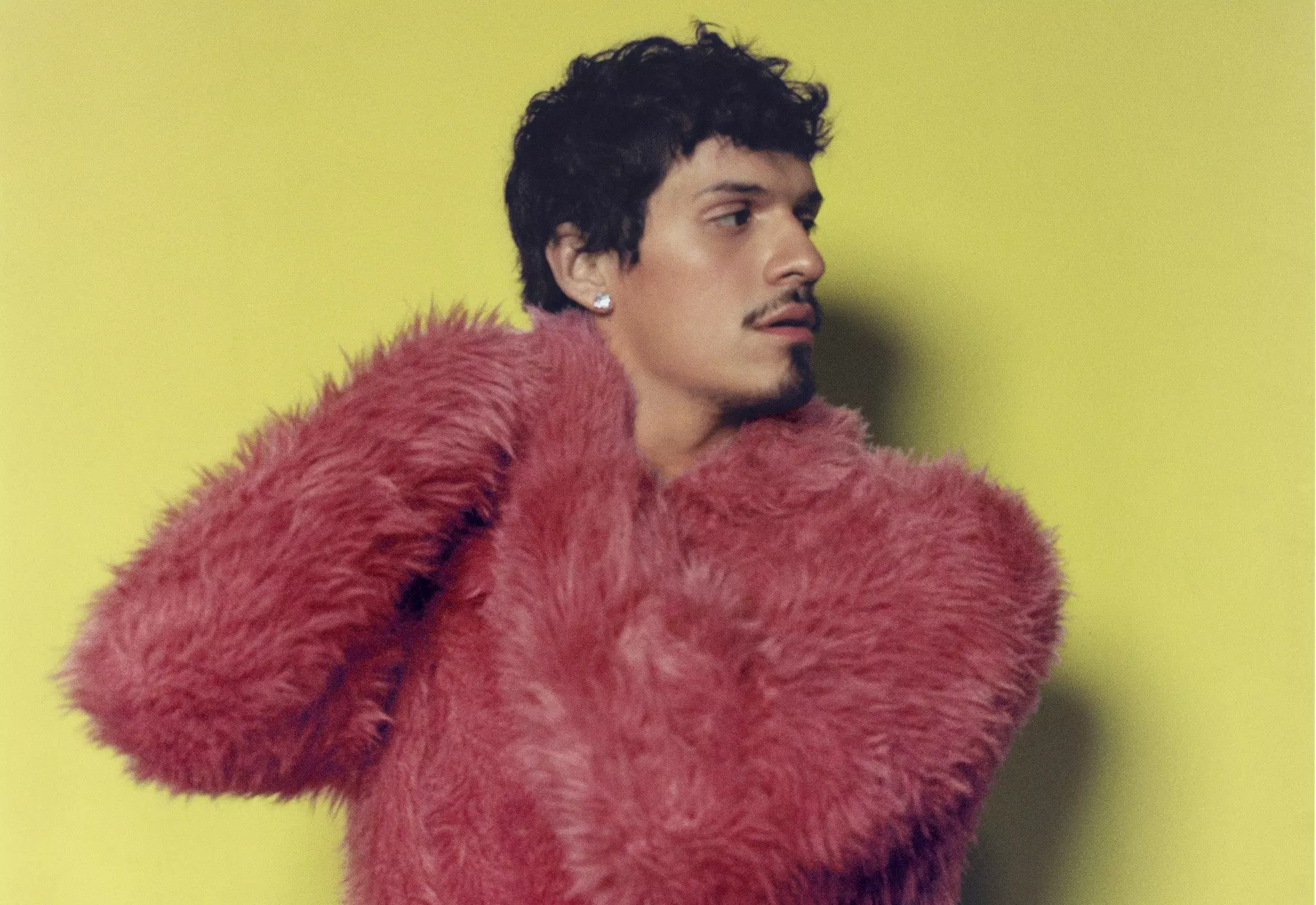

Photo: Aitor Laspiur

interview

Omar Apollo Embraces Heartbreak And Enters His "Zaddy" Era On 'God Said No'

Alongside producer Teo Halm, Omar Apollo discusses creating 'God Said No' in London, the role of poetry in the writing process, and eventually finding comfort in the record's "proof of pain."

"Honestly, I feel like a zaddy," Omar Apollo says with a roguish grin, "because I'm 6'5" so, like, you can run up in my arms and stay there, you know what I mean?"

As a bonafide R&B sensation and one of the internet’s favorite boyfriends, Apollo is likely used to the labels, attention and online swooning that come with modern fame. But in this instance, there’s a valid reason for asking about his particular brand of "zaddyhood": he’s been turned into a Bratz doll.

In the middle of June, the popular toy company blasted a video to its nearly 5 million social media followers showing off the singer as a real-life Bratz Boy — the plastic version draped in a long fur coat (shirtless, naturally), with a blinged-out cross necklace and matching silver earrings as he belts out his 2023 single "3 Boys" from a smoke-covered stage.

The video, which was captioned "Zaddy coded," promptly went viral, helped along by an amused Apollo reposting the clip to his own Instagram Story. "It was so funny," he adds. "And it's so accurate; that's literally how my shows go. It made me look so glamorous, I loved it."

The unexpected viral moment came with rather auspicious timing, considering Apollo is prepping for the release of his hotly anticipated sophomore album. God Said No arrives June 28 via Warner Records.

In fact, the star is so busy with the roll-out that, on the afternoon of our interview, he’s FaceTiming from the back of a car. The day prior, he’d filmed the music video for "Done With You," the album’s next single. Now he’s headed to the airport to jet off to Paris, where he’ll be photographed front row at the LOEWE SS25 men’s runway show in between Sabrina Carpenter and Mustafa — the latter of whom is one of the few collaborators featured on God Said No.

Apollo’s trusted co-writer and producer, Teo Halm, is also joining the conversation from his home studio in L.A. In between amassing credits for Beyoncé (The Lion King: The Gift), Rosalía and J Balvin (the Latin GRAMMY-winning "Con Altura"), SZA ("Notice Me" and "Open Arms" featuring Travis Scott) and others, the 25-year-old virtuoso behind the boards had teamed up with Apollo on multiple occasions. Notably, the two collabed on "Evergreen (You Didn’t Deserve Me At All)," which helped Apollo score his nomination for Best New Artist at the 2023 GRAMMYs.

In the wake of that triumph, Apollo doubled down on their creative chemistry by asking Halm to executive produce God Said No. (The producer is also quick to second his pal’s magnetic mystique: "Don't get it twisted, he's zaddy, for sure.")

Apollo bares his soul like never before across the album’s 14 tracks, as he processes the bitter end of a two-year relationship with an unnamed paramour. The resulting portrait of heartbreak is a new level of emotional exposure for a singer already known for his unguarded vulnerability and naked candor. (He commissioned artist Doron Langberg to paint a revealing portrait of him for the cover of his 2023 EP Live For Me, and unapologetically included a painting of his erect penis as the back cover of the vinyl release.)

On lead single "Spite," he’s pulled between longing and resentment in the wake of the break-up over a bouncing guitar riff. Second single "Dispose of Me" finds Apollo heartsick and feeling abandoned as he laments, "It don’t matter if it’s 25 years, 25 months/ It don’t matter if it’s 25 days, it was real love/ We got too much history/ So don’t just dispose of me."

Elsewhere, the singer offers the stunning admission that "I would’ve married you" on album cut "Life’s Unfair." Then, on the very next song — the bumping, braggadocious "Against Me" — Apollo grapples with the reality that he’s been permanently altered by the love affair while on the prowl for a rebound. "I cannot act like I’m average/ You know that I am the baddest bitch," he proclaims on the opening verse, only to later admit, "I’ve changed so much, but have you heard?/ I can’t move how I used to."

More Omar Apollo News & Videos

Omar Apollo Embraces Heartbreak And Enters His "Zaddy" Era On 'God Said No'

How Danna Paola Created 'CHILDSTAR' By Deconstructing Herself

On Omar Apollo's New EP 'Live for Me,’ Limitless Experimentation Created Catharsis

Listen To GRAMMY.com's LGBTQIA+ Pride Month 2023 Playlist Featuring Demi Lovato, Sam Smith, Kim Petras, Frank Ocean, Omar Apollo & More

Omar Apollo On “Evergreen,” Growth & Longing

Given the personal subject matter filling God Said No — not to mention the amount of acclaim he earned with Ivory — it would be understandable if Apollo felt a degree of pressure or anxiety when it came to crafting his sophomore studio set. But according to the singer, that was entirely not the case.

"I feel like I wouldn’t be able to make art if I felt pressure," he says. "Why would I be nervous about going back and making more music? If anything, I'm more excited and my mind is opened up in a whole other way and I've learned so much."

In order to throw his entire focus into the album’s creation, Apollo invited Halm to join him in London. The duo set up shop in the famous Abbey Road Studios, where the singer often spent 12- to 13-hour days attempting to exorcize his heartbreak fueled by a steady stream of Aperol spritzes and cigarettes.

The change of scenery infused the music with new sonic possibilities, like the kinetic synths and pulsating bass line that set flight to "Less of You." Apollo and Halm agree that the single was directly inspired by London’s unique energy.

"It's so funny because we were out there in London, but we weren't poppin' out at all," the Halm says. "Our London scene was really just, like, studio, food. Omar was a frickin' beast. He was hitting the gym every day…. But it was more like feeding off the culture on a day-to-day basis. Like, literally just on the walk to the studio or something as simple as getting a little coffee. I don't think that song would've happened in L.A."

Poetry played a surprisingly vital role in the album’s creation as well, with Apollo littering the studio with collections by "all of the greats," including the likes of Ocean Vuong, Victoria Chang, Philip Larkin, Alan Ginsberg, Mary Oliver and more.

"Could you imagine making films, but never watching a film?" the singer posits, turning his appreciation for the written art form into a metaphor about cinema. "Imagine if I never saw [films by] the greats, the beauty of words and language, and how it's manipulated and how it flows. So I was so inspired."

Perhaps a natural result of consuming so much poetic prose, Apollo was also led to experiment with his own writing style. While on a day trip with his parents to the Palace of Versailles, he wrote a poem that ultimately became the soaring album highlight "Plane Trees," which sends the singer’s voice to new, shiver-inducing heights.

"I'd been telling Teo that I wanted to challenge myself vocally and do a power ballad," he says. "But it wasn't coming and we had attempted those songs before. And I was exhausted with writing about love; I was so sick of it. I was like, Argh, I don't want to write anymore songs with this person in my mind."

Instead, the GRAMMY nominee sat on the palace grounds with his parents, listening to his mom tell stories about her childhood spent in Mexico. He challenged himself to write about the majestic plane tree they were sitting under in order to capture the special moment.

Back at the studio, Apollo’s dad asked Halm to simply "make a beat" and, soon enough, the singer was setting his poem to music. (Later, Mustafa’s hushed coda perfected the song’s denouement as the final piece of the puzzle.) And if Apollo’s dad is at least partially responsible for how "Plane Trees" turned out, his mom can take some credit for a different song on the album — that’s her voice, recorded beneath the same plane tree, on the outro of delicate closer "Glow."

Both the artist and the producer ward off any lingering expectations that a happy ending will arrive by the time "Glow" fades to black, however. "The music that we make walks a tightrope of balancing beauty and tragedy," Halm says. "It's always got this optimism in it, but it's never just, like, one-stop shop happy. It's always got this inevitable pain that just life has.

"You know, even if maybe there wasn't peace in the end for Omar, or if that wasn't his full journey with getting through that pain, I think a lot of people are dealing with broken hearts who it really is going to help," the producer continues. "I can only just hope that the music imparts leaving people with hope."

Apollo agrees that God Said No contains a "hopeful thread," even if his perspective on the project remains achingly visceral. Did making the album help heal his broken heart? "No," he says with a sad smile on his face. "But it is proof of pain. And it’s a beautiful thing that is immortalized now, forever.

"One day, I can look back at it and be like, Wow, what a beautiful thing I experienced. But yeah, no, it didn't help me," he says with a laugh.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

2024 Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony: Watch Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Gojira & More Perform

Ice Spice Is The Drill Queen On 'Y2K!': 5 Takeaways From Her Debut Album

New Music Friday: Listen To New Songs From Halsey, MGK And Jelly Roll, XG & More

Watch Young MC Win Best Rap Performance In 1990

The Red Clay Strays Offer A New Kind Of Religion With 'Made By These Moments'

.jpg)

Photo: Michael Kovac/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Beyoncé's Heartfelt Speech For Her Record-Breaking Win In 2023

Relive the night Beyoncé received a gramophone for Best Dance/Electronic Album for 'RENAISSANCE' at the 2023 GRAMMYS — the award that made her the most decorated musician in GRAMMY history.

Six years after her last solo studio album, Beyoncé returned to the music industry with a bang thanks to RENAISSANCE. In homage to her late Uncle Johnny, she created a work of art inspired by the sounds of disco and house that wasn't just culturally impactful — it was history-making.

At the 2023 GRAMMYs, RENAISSANCE won Best Dance/Electronic Album. Marking Beyoncé's 32nd golden gramophone, the win gave the superstar the record for most gramophones won by an individual act.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, revisit the historic moment Queen Bey took the stage to accept her record-breaking GRAMMY at the 65th Annual GRAMMY Awards.

"Thank you so much. I'm trying not to be too emotional," Beyoncé said at the start of her acceptance speech. "I'm just trying to receive this night."

With a deep breath, she began to list her praises that included God, her family, and the Recording Academy for their continued support throughout her career.

"I'd like to thank my Uncle Johnny, who is not here, but he's here in spirit," Beyoncé proclaimed. "I'd like to thank the queer community for your love and inventing this genre."

Watch the video above for Beyoncé's full speech for Best Dance/Electronic Album at the 2023 GRAMMYs. Check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind.

Tune into the 2024 GRAMMYs on Sunday, Feb. 4, airing live on the CBS Television Network (8-11:30 p.m. LIVE ET/5-8:30 p.m. LIVE PT) and streaming on Paramount+ (live and on-demand for Paramount+ with SHOWTIME subscribers, or on-demand for Paramount+ Essential subscribers the day after the special airs).

Photo: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Lizzo Thanks Prince For His Influence After "About Damn Time" Wins Record Of The Year In 2023

Watch Lizzo describe how Prince’s empowering sound led her to “dedicate my life to positive music” during her Record Of The Year acceptance speech for “About Damn Time” at the 2023 GRAMMYs.

Since the start of her career, four-time GRAMMY winner Lizzo has been making music that radiates positive energy. Her Record Of The Year win for "About Damn Time" at the 2023 GRAMMYs proved that being true to yourself and kind to one another always wins.

Travel back to revisit the moment Lizzo won her award in the coveted category in this episode of GRAMMY Rewind.

"Um, huh?" Lizzo exclaimed at the start of her acceptance speech. "Let me tell you something. Me and Adele are having a good time, just enjoying ourselves and rooting for our friends. So, this is an amazing night. This is so unexpected."

Lizzo kicked off her GRAMMY acceptance speech by acknowledging Prince's influence on her sound. "When we lost Prince, I decided to dedicate my life to making positive music," she said. "This was at a time when positive music and feel-good music wasn't mainstream at that point and I felt very misunderstood. I felt on the outside looking in. But I stayed true to myself because I wanted to make the world a better place so I had to be that change."

As tracks like "Good as Hell" and "Truth Hurts" scaled the charts, she noticed more body positivity and self-love anthems from other artists. "I'm just so proud to be a part of it," she cheered.

Most importantly, Lizzo credited staying true to herself despite the pushback for her win. "I promise that you will attract people in your life who believe in you and support you," she said in front of a tearful audience that included Beyoncé and Taylor Swift in standing ovation, before giving a shout-out to her team, family, partner and producers on the record, Blake Slatkin and Ricky Reed.

Watch the video above for Lizzo's complete acceptance speech for Record Of The Year at the 2023 GRAMMYs. Check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind, and be sure to tune into the 2024 GRAMMYs on Sunday, Feb. 4, airing live on the CBS Television Network (8-11:30 p.m. LIVE ET/5-8:30 p.m. LIVE PT) and streaming on Paramount+ (live and on-demand for Paramount+ with SHOWTIME subscribers, or on-demand for Paramount+ Essential subscribers the day after the special airs).

Photo: Kevin Mazur

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Harry Styles Celebrates His Fellow Nominees (And His Biggest Fan) After Album Of The Year Win In 2023

Revisit the moment Harry Styles accepted the most coveted award of the evening for 'Harry's House' and offered a heartfelt nod to his competitors — Beyoncé, Adele, Lizzo, Coldplay and more.

After a wildly successful debut and sophomore record, you'd think it was impossible for Harry Styles to top himself. Yet, his third album, Harry's House, proved to be his most prolific yet.

The critically acclaimed project first birthed Styles' record-breaking, chart-topping single, "As It Was," then landed three more top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 with "Late Night Talking," "Music for a Sushi Restaurant" and "Matilda." The album and "As It Was" scored Styles six nominations at the 2023 GRAMMYs — and helped the star top off his massive Harry's House era with an Album Of The Year win.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, revisit Styles' big moment from last year's ceremony, which was made even more special by his superfan, Reina Lafantaisie. Host Trevor Noah (who will return as emcee for the 2024 GRAMMYs) handed the mic to Lafantaisie to announce Styles as the winner, and the two shared a celebratory hug before Styles took the mic.

"I've been so, so inspired by every artist in this category," said Styles, who was up against other industry titans like Beyoncé, Adele, Lizzo and Coldplay. "On nights like tonight, it's important for us to remember that there is no such thing as 'best' in music. I don't think any of us sit in the studio, making decisions based on what will get us [an award]."

Watch the video above to see Harry Styles' complete acceptance speech alongside his collaborators Kid Harpoon and Tyler Johnson. Check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind, and be sure to tune into the 2024 GRAMMYs on Sunday, Feb. 4, airing live on the CBS Television Network (8 -11:30 p.m. LIVE ET/5-8:30 p.m. LIVE PT) and streaming on Paramount+ (live and on demand for Paramount+ with SHOWTIME subscribers, or on demand for Paramount+ Essential subscribers the day after the special airs).