Photo: Pooneh Ghana

Fiddlehead's Next Show Isn't Guaranteed. As Their New Album Stresses, Neither Is Tomorrow.

"The band is clearly not our life," says Pat Flynn of Fiddlehead's relative scarcity onstage. But their new album, 'Death is Nothing to Us,' is drenched in life, consumed with the quandaries of existence.

You don't see Fiddlehead crisscrossing the globe over and over; if you miss them in your area, chances are they won't be back in a few months. In fact, there's no assurance they'll return in the foreseeable future — or ever.

"There's no guarantee that it's going to happen again," says vocalist Pat Flynn, in an interview about their new album, Death is Nothing to Us. "Because the band is clearly not our life."

The rhythms of domesticity rumble around Flynn; because "my office was invaded by my children," he's Zooming from another room. (When he told them he was "talking to GRAMMY," the kids misunderstood it to mean Grandma.)

For the hardcore-adjacent supergroup — composed of members of Basement, Have Heart and more — life responsibilities have engendered a "scarcity effect."

But instead of rendering Fiddlehead lost in the shuffle, this has made their performances unforgettable — both for the audience and band.

"I've been in bands where we've toured for three to six weeks at a time, and I can barely remember one from the other," adds their guitarist, Alex Henery, from a parallel Zoom window.

But with Fiddlehead? "I can track down most shows in my brain when I think about it because there's not that many," Henery says. "It really does feel special, and I really never want to wish away that time."

Out Aug. 18, Death is Nothing to Us frequently evokes a feeling of holding onto the present. "Face it all/ Replace with love," Flynn repeatedly exhorts in the combustible "Sullenboy." In the aching "Fifteen to Infinity," he sings of heaven being attainable on the sofa, "in the nothingness of our night."

And the final line, from closer "Going to Die," seems to encapsulate the album's mortality-haunted essence: "See you on the other side/ I know I will/ But I don't wanna die."

Granted, Fiddlehead didn't become a "grief band" by some grand design. But from their first demo, that's been a major component of their emotional landscape.

"It just so happened that I was in a pretty thick stage of dealing with the loss of my father," Flynn says. "So, that first record [2018’s Springtime and Blind] really connected and I think a lot of people connected with it in sharing stories of profound losses in their lives. The positive response was motivating to continue the band."

This theme has seemingly crescendoed with Death is Nothing to Us, a 12-song, 27-minute volley of life-affirming, kinetic rock. Read on for an interview with Flynn and Henery about how Fiddlehead's third album came to be.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Pat, you grew up Catholic; in "True Hardcore (II)," you sing about scenesters who are "pseudo and false to the core/ keeping the gates closed." What's the overlap between religious sanctimony and subcultural gatekeeping?

Pat Flynn: Growing up in a Catholic education, perhaps I've always been skeptical of those who are trying to draw too firm of a line.

But in just terms of gatekeeping, to me, it's more like that's how you kill art, that's just how you destroy it. When you start to codify too many things and you label the genre, you make it really intensively small.. .it becomes like you have to look a certain way to sound a certain way.

I'm skeptical of retrospective psychoanalysis, but, sure, I think that there's probably some type of overlap of there being too many strict codes — which is a lot of what a Catholic education has to be. And I've always really appreciated the power of the individual as opposed to the mediator.

[Catholicism is] a top-down structure. And when I was in high school, the top-down structure was definitely a motivator to find something like the hardcore scene really appealing; it was an equalizer.

I know why I felt compelled to write the lyrics for "True Hardcore (II)" more specifically, but the record in itself seems to really follow my own path with my struggles of hitting the low points.

I can't deny the fact that for the last 24 to 25 years, I've always found hardcore to be a place that's kind of uplifting and helped me bounce back. I just see it as totally precious and valuable.

And so the idea when some people try to make it too exclusive, or a selectively chosen community, it really agitated me. It's taken away the human appeal to thriving in life. I don't know if that sounds all corny, but it's an interesting song.

Has that individual-over-group ethos always been at the core of Fiddlehead's music?

Flynn: I specifically and explicitly remember saying, "Hey, let's just write as if we're never going to play out and play live," so that we can keep a pure sound.

And I think I was definitely burnt out with too much exposure to a community, and dealing with the noise of the community with my previous band [Have Heart]. And so I just wanted to get back to just writing for the sake of the enjoyment of creation.

However, when it began to connect with people in a really positive way, I was very quickly reminded of the value of sharing your art with a larger world around you. It very much went on to inspire writing the second record, and it continues to inspire the band to continue creating art.

Alex Henery: I was thinking back to early shows the other day, and it was awesome, honestly.

Back then, all you'd care about is just playing the show. There were no distractions; we weren't trying to win anyone over. It was purely just that we'd written these songs we liked and we wanted to play them.

We always talk about some of those early shows, as it doesn't get much more pure than that or us. Getting back to the core of it was definitely really important to me.

How would you guys characterize the period of time between Between the Richness and Death is Nothing to Us?

Flynn: It's been pretty positive. We actually started writing this record before Between the Richness came out. Between the Richness was recorded in February of 2020, and obviously, the world kind of stopped.

We didn't know if shows were ever coming back. There was actually no guarantee that we would ever play music live again. And yet we were still meeting up in our barn just putting music together because that just felt right.

We don't play too much, and so it really does create a nice scarcity effect, if you will. People feel like they really have to — and especially, very much so us — really soak up the live moment.

We all have different lives; we all have very different ambitions. It's not that we're always teetering on the brink of breaking up or anything like that. But it does make us savor the moment, and it makes the shows to be as sacred as you can make them — and as intense, in the moment, and cathartic, in many ways.

We're just playing and continuing to write, and allowing for the interactions with the people to inform our ideas about writing. And it's been a pretty great reciprocal relationship with the people who have been supporting us through the last few years.

I think the record has been a bit of a reflection of areas that we wanted to explore musically and lyrically that we had not before.

Henery: I was writing out of the really strong desire, after being cooped up in my room for so long, of getting to play loud — practicing and just turning the amps up loud and letting it out. It was awesome, and I think we all needed that at that point.

Fast forward all the way 'til now — where everything has changed again, and we do have shows and I feel like we appreciate it even more than we already did.

I'm very excited to be able to travel and play music. We're about to go to Southeast Asia. I'm excited to go to some places I've never been before and play in front of a bunch of different audiences, and play this new record for people.

It's crazy to think about it starting all the way back then, and coming to fruition now. I forgot how long this journey's been.

Flynn: [Regarding] the record — it's cool in a sense. We don't really tinker too much with the songs. It's a fairly organic process when we're writing it. Ideas just sort of pop out and we don't want to overdo it, overproduce it.

I think a lot of that has to do with trying to keep the magic of the writing moment. A lot of these songs that end up getting recorded in the studio are pretty raw, other than the fact that we're just recording them again. We didn't change too many things.

I like that. It's special. Nothing is perfect. In a day in which there's increasing motivation to try and make it and do the right thing that the masses want to hear, what's going to be digestible and yada, yada, yada… this has felt pretty pure.

Henery: We've never had the luxury of going in for a month, two months and being in the studio and really just musing over the song. One song is maybe three days, four days.

I don't even know if I believe in the perfect take. I think we all just, we go until we feel that it's good and then we keep it moving. And I think that you hear that in this record. It has a natural feel rather than OK, again, again, again.

I think we're more of a "feel band" and we go off that, so there are imperfections here and there. But I think that adds to the charm of it.

And we have an amazing engineer, Chris Teti. I'm glad that we're not with someone who's like, "No, let's just do it another 50 times; maybe there's something extra we could find in there." Let's just keep it moving and see what else we can come up with.

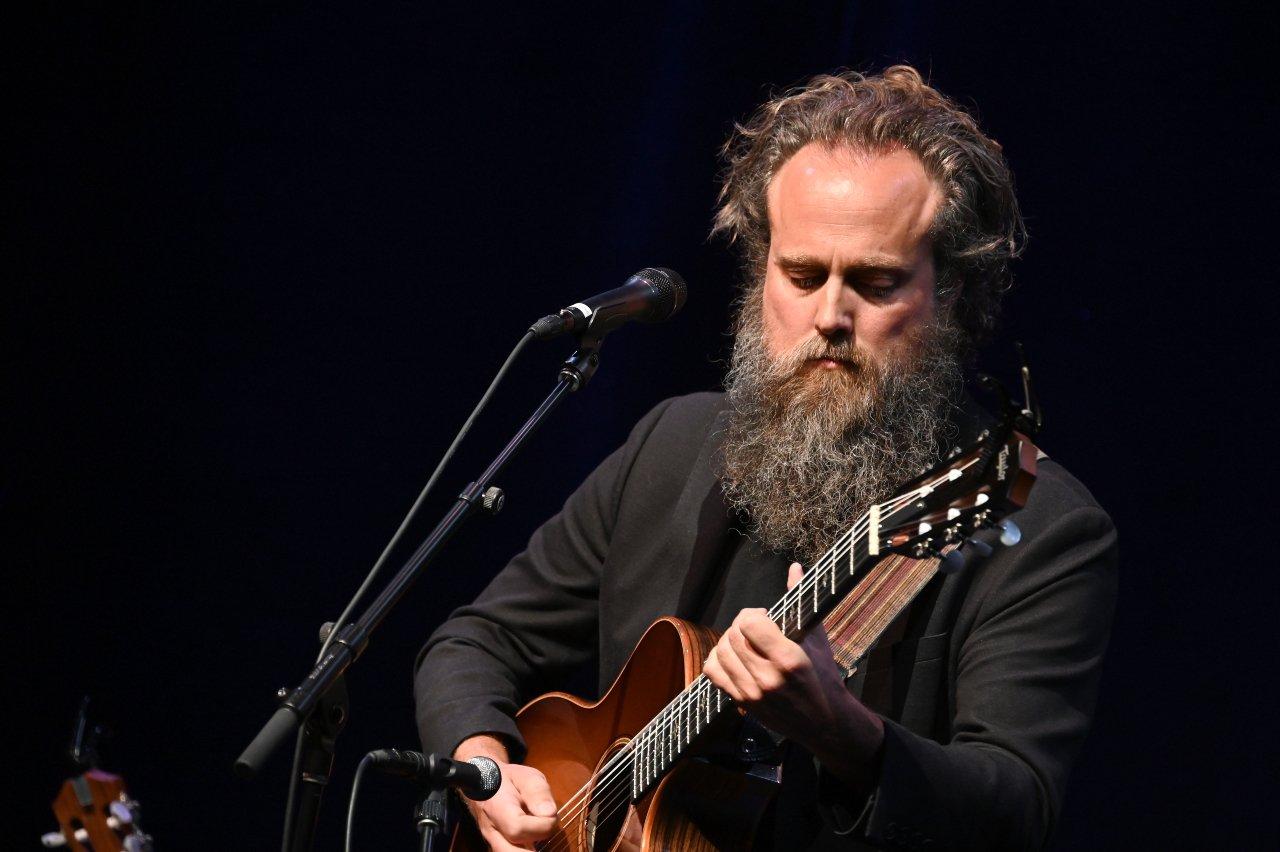

*Fiddlehead. Photo: Pooneh Ghana*

With that in mind, tell me how you wanted the album to grab people on an aural, visceral level.

Henery: [Alex] Dow, our guitarist, brought the riff for the opening record ["The Deathlife"]. He showed it to Pat, and the two of them instantly had the vision. I was the last person to gain that vision. It just wasn't clicking.

It wasn't until we fully hit the studio that, hearing the lyrics and the way that Pat performed the vocals, [I realized] it's just such a stark contrast to our last record, which is such a build and then a final release. This was just straight "bash over the head."

I love that it is such a different approach and I just couldn't see the vision straight away. But we got there in the end, and maybe it's just that I was hungry and tired or something. I think I'd flown in from a different tour to go practice — not a good combo for me.

It is kind of interesting how we work. I don't have any experience in musical theory, didn't go to music school. It's very feel-based, and Pat really has that too.

Pat, you have a good perception of what story you want this song to tell, or what journey we want to go on. I'm more just like: if this feels good, I'm going to play it. Then I'll go from there and the building blocks then begin to stack up.

Flynn: Yeah, the opening track is definitely a clamoring at the gates.

If you're interested in creating a collection of songs that work together to take a listener on a journey, the sequencing is so, so important. There's a desperation that I thought we didn't really explore on previous records, and I just thought that a really great way to create this [feeling]. We're not ringing the doorbell; we're slamming it, breaking it open.

And then it's followed by a very pleasant sounding song that is very bright, but somehow has some of the most dreadful, depressed lyrics on top of it. So if it's not this sonic bashing, it really is this tug and pull of a variety of emotions.

The record ends at the antithesis, lyrically, of where it began. And it's fun: if you put it on repeat, you're going through a variety of human emotions.

Henery: I definitely think this isn't an unbelievably massive hard left or right turn with this new record. But I think we've established that we're not going to try and recreate what we just did.

Hopefully, that's enjoyable from a listener standpoint: that there's a story here that can continue as opposed to being capped out.

On Militarie Gun's Life Under The Gun, Ian Shelton Invites You Inside His Hornet's Nest Of A Mind

Photo: PLEDIS Entertainment

news

5 Songs To Get Into Seventeen, Ahead Of New Album '17 Is Right Here'

The 13-member K-pop group has been going strong, selling over 16 million albums since 2015. On April 29, they'll release '17 Is Right Here,' a compilation of some of their most impactful songs. Dive into the world of Seventeen with five essential songs.

Seventeen is more than just a K-pop group; it's a musical phenomenon that challenges conventions and redefines what it means to be a star in the South Korean music scene. Formed in 2015, the group consists of 13 members who are divided into vocal, hip-hop, and performance sub-units.

S.Coups, Jeonghan, Joshua, Jun, Hoshi, Wonwoo, Woozi, Dk, Mingyu, The8, Seungkwan, Vernon, and Dino have garnered a growing and dedicated global fandom known as Carats, who closely follow their every move. For the group, their fans are a significant part of their growth.

"We're definitely more confident than before through our growth. The growth of our Carats and the amount of support that they show us just gives us so much confidence", member Joshua told GRAMMY.com in 2022.

The self-produced group has a clear philosophy: Create relevant and innovative music that resonates. They don't adhere to stereotypes or definitions, but constantly strive to evolve and explore new sonic territories. This creative and authentic approach has been an integral part of the group's enduring success.

Seventeen wrapped up 2023 with over 16 million albums sold. On April 29, they'll release 17 Is Right Here, a compilation of some of their most impactful songs. For those looking to dive into the world of Seventeen, here are five essential songs to kickstart this exciting musical journey.

"Don't Wanna Cry" (2017)

The lead single from the mini album Al1, "Don't Wanna Cry" details the struggle of dealing with pain and loss. The track delves into the complex feelings of no longer having a loved one around, while holding onto the hope that they might return.

"Don't Wanna Cry" is a striking example of the group's openness and vulnerability with their fans. The song's raw emotions are deeply personal and relatable, depicting a struggle with pain and loss.

"To You" (2021)

The lively and heartwarming track "To You," from the ninth mini album Attacca, is a beautiful reflection on love and gratitude. It's the kind of song that inspires you to throw your arms open wide, sing out loud, and feel every word with your eyes closed.

With its repeated phrase of "I always need you," the song emphasizes the comfort of having someone dependable in your life. "To You" exemplifies Seventeen's remarkable ability to seamlessly combine emotional depth with infectious dance rhythms, showcasing their talent for creating simultaneously heartfelt and energetic tracks.

"Hot" (2022)

A song to enjoy not just in the summer, but on any day of the year, "Hot" was released in 2022 as part of the album Face the Sun.

Through metaphors involving fire and the sun, the group repeatedly chants the word "Hot" reflecting a sense of confidence and the freedom to live passionately, while also encouraging listeners to express themselves boldly without fear.

Reflecting the group's identity, "Hot" embraces themes of confidence, passion, and fearless self-expression — qualities that resonate with the group's image and message.

"Super" (2023)

An authentic anthem about unity, "Super" celebrates the power of teamwork and mutual support, as highlighted by the iconic chorus "I love my team, I love my crew." "Super" exemplifies how Seventeen functions as one cohesive group despite its numerous members, emphasizing their strong bond and collective spirit.

The song's title — a reference to Son Goku (손오공) from the famous anime "Dragon Ball" — is featured on the album FML, which in sold over 6.4 million copies in 2023 according to Pledis Entertainment, earning the title of the world's best-selling album.

"God of Music" (2023)

An anthem to the universal language of music and its remarkable ability to forge connections across continents, "God of Music," from Seventeen's 11th mini album, Seventeenth Heaven, is a track that moves you to dance from the very first beat.

The group emphasizes how music breaks down barriers, turning strangers into friends and uplifting people worldwide, regardless of language differences. In their accompanying music video, the members conclude with a heartfelt message: Music is a force that brings people together.

SEVENTEEN Performs A High-Octane Version Of "VERY NICE" | Press Play At Home

Photo: Stephen J. Cohen/Getty Images

news

Iron & Wine Offers 'Light Verse': Sam Beam On His New Album, 2000s-Era Pigeonholing & Turning Up The Whimsy

If your memories of Iron & Wine are of melancholic folk songs for drizzly days, wipe your glasses dry: singer Sam Beam is a richly multidimensional artist. As displayed on his sophisticated, fancy-free new album with killer collaborators, 'Light Verse.'

Upon first impression, Sam Beam of Iron & Wine’s got a wildly endearing trait: he laughs even when something’s not explicitly funny. Even through Zoom, the man most of us know for aching, desolate folk songs will give you a tremendous lift.

"I like to joke around and stuff with my friends," the beardy and serene Beam tells GRAMMY.com — those friends including fellow mellow 2000s favorites, like Andrew Bird and Calexico. "Honestly, it's harder to be serious than it is to joke around most of my friends."

That’s partly what spurred the four-time GRAMMY nominee to make the shimmering, whimsical Light Verse. While it follows 2023’s soundtrack to the documentary Who Can See Forever, and 2019’s Calexico collaboration Years to Born, in relatively short order, it’s still the first proper Iron & Wine album since 2017’s Beast Epic.

Getting to the space to write waggish songs like "Anyone’s Game" ("First they kiss their lucky dice and then they dig themselves a grave/ They do this until it’s killing them to try") wasn’t easy. In conversation, Beam mentions "the pandemic that put me on my ear." In press materials, he expanded on exactly how it did.

"While so many artists, fortunately, found inspiration in the chaos, I was the opposite and withered with the constant background noise of uncertainty and fear," Beam wrote. "The last thing I wanted to write about was COVID."

"And yet, every moment I sat with my pen," he continued, "it lingered around the edges and wouldn’t leave. I struggled to focus until I gave up, and this lasted for over two years."

Thankfully, a Memphis session with singer/songwriter Lori McKenna relaxed his "creative muscles" and a series of tours and collaborations loosened him up even more. Beam assembled a dream team of musicians in Laurel Canyon, and the rest is history — Light Verse is a sumptuous delight.

Read on for how it came to be — and much more.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Light Verse is the first non-collaborative Iron & Wine album since 2017. I imagine there’s sometimes pressure to just put music out for the sake of having it out. Whatever the case, I appreciate that you put time and thought into it.

Yeah, I mean, honestly, I just like making records with other people. You can only smell your own breath so long. I enjoy putting out records, but I feel like I grow more as a musician and person by working with other people. So, I’ll probably be doing more and more of that.

I don’t feel a whole lot of pressure, one way or the other. Maybe I’m just deaf and those things are screaming at me. But I just don’t listen.

What pressures have you faced in the music industry?

Oh, there are certainly lots of pressures. One is, I should probably be on top of my social media game, but I just can't seem to engage with it. I don’t know. That's how people make their entire careers these days, but I can't find a way to sustain it.

I can't think of a way that I could, because I definitely go through days without picking up my phone at all, so I just can't. I think if I could figure out a way to make it fun, I would do it.

What do you do with the time most people spend on their screens?

Playing guitar, or I do a lot of painting. I’m not saying I never pick up my phone, but I don't think about what could I share about my breakfast to the world, I just don't think about it. I'm private.

What was the germ of the concept behind Light Verse?

I don't really usually go in with a specific idea in mind. I just like to stack the deck with people that I like to play with, or that I like what they do. And so just see what happens, throwing a bunch of ingredients that you like individually, and just seeing if it makes a soup that you like.

My idea was to go in with these folks from L.A. that I had met along the way. David Garza, I'd been wanting to play with for a long time. I'd met Tyler Chester, who plays keys, when he was playing with Andrew Bird. Griffin Goldsmith plays with Dawes.

The songs were all developed. They were a bit lighter than some of the fare that I've put out before, far as just silly rhymes. They're a little more off the cuff.

I'm kinda mining the territory of the early '70s, where the folk writers were playing with jazz musicians. It just becomes a little more orchestra, or however you want to describe it. Not quite so straightforward.

But I had these off-kilter tunes and I got an off-kilter, talented band from LA, and I was just going to see what happened. And this is what happened.

Naturally, my mind goes to Joni Mitchell playing with Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter. What are your touchstones?

Well, those Van records — Astral Weeks and stuff. All the stuff in that time when people started playing cluster-y chords. I love that music. It’s so expressive. Ron Carter playing with Roberta Flack, even. They’re gospel-blues sorts of tunes, but they’re also folky [in their] structures and melodies.

Are you a super technically proficient guitarist? Can you play those crazy chords?

[Grins] I wouldn’t be able to tell you what chord it was, but I might be able to get my hand in the shape. I don’t read music. I just learned to play by ear, but I like to play guitar a lot, so I end up stumbling on most stuff.

I also fool around with a lot of open tunings, so you end up with some cluster-y, bizarre stuff with that, for sure.

Even just paying attention to Brian Wilson — he’s not a guitarist, but I feel like his work can teach guitarists a lot about voice leading and stuff.

Definitely. A lot of those jazz voices have been absorbed by pop music. You can hear Bill Evans all over pop music, especially in the ‘90s.

**Can you take readers through the orchestration on Light Verse? It’s so shimmery and rich and unconventional.**

Thanks. Yeah, we were borrowing from some of those jazz ensembles we’re talking about, and also Brazilian music.

Honestly, that Gal Costa tune, "Baby" — it’s the most famous one — it’s my spirit animal for this record. Just between the strings and the way the guitars and rhythm section work — the sparse way it comes and goes.

We approached it fairly intuitively. But I do feel like Paul Cartwright, who did a lot of those strings and charts and stuff, played a huge role as far as the identity of this record. Outside of the lyrics and the forms and stuff, just the way that he interpreted in this really expressive way. His charts and stuff were really great — and a lot of it's him playing, stacking stuff on his own. He's really, really talented.

He also grew up in Bakersfield, and since the violin is strung the way a mandolin is, he rocks a mean mandolin. He had all these different bass mandocellos and all this stuff. He was just, "What are we working on now? Hand me that thing," and just did all kinds of coloring. It's great.

Can you talk about approaching your work with more whimsy and color?

I feel like for some reason, for the longest time when I sat down to write a song, it was a time to say what I mean. And so when it came time to write a song, it ended up being really somber. Some of it is acidic, but somber for the most part.

Whereas for this one, I was just looking for more balance. Maybe I'm just too old to be impressed by that stuff, so I like balance — something that can resonate on something that people recognize but also is fun at the same time.

You can embrace both things at one time, that life is hard and also silly. And so that was the MO going into this one, and a lot of the songs that I chose to record were because they had both of those things going on at one time.

You’re a three-dimensional artist, but marketing can flatten musicians. Growing up with Iron & Wine, it tended to be packaged as "chill music for rainy days" or some such. Primary colors.

We all do that. We always try to define something. You know what I mean? You want to understand it, and by understanding, control it and define it.

All artists deal with that, for sure. It's frustrating when you want to be recognized. You want them to pay attention to other things, but it's also that we just want to be appreciated. Artists want to be appreciated for every little gesture we make, and it's not realistic. We do our best.

I feel like if you work hard, hopefully the stars will align and people will appreciate what you do.

What do you remember about the atmosphere of the music industry, back when big songs I don’t need to name came out?

You mean the vampire song and stuff?

Yeah.

It's definitely a lot different. The internet upended everything. I squeezed and slipped in the door just as the door was closing on the closed circuit of records and stuff.

It was more of a monoculture, where everyone was having the same conversation about the same groups of musicians. Now, [you can have] the entire history of recorded music at any moment of the day. It's hard to have the same conversation about things. That's been a big difference.

When you hang out and collaborate with friends like Andrew Bird, is there ever a sense of "We survived, we’re the class of 2000-whatever"?

Well, for one thing, it's hard to realize that you've been making music that long. Most bands don't even last that long. It's insane.

But it's also, I just feel really blessed. Maybe it's because I never studied music — my career feels like a fluke. I still feel blessed that people are still interested, blessed that I'm able to do this. I never thought it was in the cards, and so I just feel really lucky.

Sam Beam of Iron & Wine. Photo: Kim Black

I feel like one route to longevity is self-containment. Namely, self-production, which you’ve done forever. Where are you at with that journey?

I like autonomy. I see the musicians who are also producers in their own right, so usually I have a room full of producers and I don't end up using them. We all think everyone should get a producer credit, but I take it because I'm selfish.

But I like having the autonomy. That's why I still release on an independent record label. I like steering the boat. We're all steering around the same fog, but I don't like to have someone else to bitch about. I just bitch about myself.

It releases you from those moments where it’s like, "Sam, sales are down. We’ve got to get you in with Danger Mouse," or something.

Well, hell, man, I’d do that. But I know what you mean. The idea committees I imagine for most artists are really brutal.

Trend-wise, there’s pressure to chase trains that can lead to all music sounding the same.

The things that you're offered, really teach you a lot about what you're in it for. Or it's also after a while, your reasons for doing it change. I don't fault people for reaching for the ring, but I also feel like I was lucky in the sense that I was just doing it for fun.

And all the songs that have been popular were a surprise to me. The songs of mine that were embraced in a way were a surprise. I felt like there were others that might've been more popular or something, or I would've chosen to promote.

So, the lesson I learned is you have no idea. Just put your best into each one and see what happens because you really can't predict what's going to happen. In that sense, if you're trying to be popular or record something that sticks, you're trying to emulate something that's proven to be popular. And for me, that seemed like a recipe for disaster from the beginning.

I feel like if you wrote a really great song in the ‘90s or 2000s, it’d get heard. Not so much in 2024. You need to take it to market and bother everybody about it.

Yeah, it's a tricky thing. The internet has been wonderful as far as we have access to all kinds of stuff that we didn't have access to before, but it just also disperses all the attention. It's hard. There's a lot of great music happening right now — but like you say, you might never know.

What are you checking out lately that you’re really connecting with? Past or present.

I heard a great tune the other day by this woman named Barbara Keith, "Detroit or Buffalo," from 1972. Obviously not contemporary, but it was incredible. I'd never heard it before. I'm checking out stuff, trying to keep up. It's hard.

What do you like that would make people say, "Sam Beam likes that?"

Oh, in my case, it’s all over the place. I’m not real proprietorial with music. It’s something to experience. I’m not so much into dance music, but I like a lot of really intense electronic music. That might be surprising. Who knows?

Everything’s out there for the taking. It’s the universal buffet.

I think everyone can recognize a musical omnivore, and then not be surprised.

Anything else about Light Verse you’re raring to talk about?

We did get to sing with Fiona Apple, which was really a treat. That was unexpected, but a very welcome experience. And she turned a regular song into an incredible duet, which was really a surprise and a blessing.

What was it like working with Fiona?

I never actually met her. Because of the way technology works these days, she was in a whole other state and sent us the track. But a lot of the people that were playing and a lot of people in the room; we share band members like Sebastian Steinberg, and David Garza plays with her a lot too.

One of the reasons that I recorded there in LA with Dave Way is because they had made their last few records with Dave, and Sebastian had been in my ear about, "You got to go record Dave." And it turns out he was right. It was great. She had a lot of friends in the room, so it wasn't too hard to convince her.

Beirut's Zach Condon Lost His Sense Of Self — Then Found It Within A Church Organ

Photo: Apex Visions

interview

On 'Princess Pop That,' Rapper Anycia Wants You To Feel Like "The Baddest Bitch"

"It's a no judgment zone," Anycia says of her new album. The Atlanta rapper discusses the importance of maintaining individuality, and using her music for healing.

Twenty-six-year-old rapper Anycia truly lives in the present. The Atlanta-born artist describes her most viral hits as if they were everyday experiences — she's simply going out of town on "BRB" and mad at a partner in "Back Outside" featuring Latto.

Despite her calm demeanor and cadence, Anycia is a self-proclaimed "firecracker" and credits her success to her long-held confidence.

"I [command] any room I walk in, I like to introduce myself first — you never have to worry about me walking into the room and not speaking," Anycia tells GRAMMY.com. "I speak, I yell, I twerk, I do the whole nine," adding, "I see tweets all the time [saying] ‘I like Anycia because she doesn’t rap about her private parts’... are y’all not listening?"

With authenticity as her cornerstone, Anycia's genuine nature and versatile sound appeal broadly. On her recently released sophomore LP, Princess Pop That, Anycia's playful personality, unique vocal style and skillful flow are on full display. Over 14 tracks, Anycia keeps her usual relaxed delivery while experimenting with different beats from New Orleans, New York, California, and of course, Georgia.

"I'm learning to be myself in different elements. I'm starting to take my sound and make it adapt to other beats and genres," she says. "But this whole album is definitely a little showing of me dibbling and dabbling.

The rising hip-hop star gained traction in June 2023 with her sultry single, "So What," which samples the song of the same name by Georgia natives Field Mob and Ciara. When Anycia dropped the snippet on her Instagram, she only had a "GoPro and a dream." Today, she has millions of views on her music videos, collaborations with artists like Flo Milli, and a critically acclaimed EP, Extra. On April 26, she'll release her debut album, Princess Pop That, featuring Cash Cobain, Luh Tyler, Kenny Beats, Karrahbooo and others.

Ahead of the release of Princess Pop That, Anycia spoke with GRAMMY.com about her influences, maintaining individuality, working with female rappers, and using her music as a therapeutic outlet.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Where did the title Princess Pop That come from?

Princess Pop That is my little alter ego, and my Twitter and finsta name. It's kind of like a Sasha Fierce/Beyoncé type of situation.

The cover of your album gives early 2000 vibes. Is that where you draw most of your inspiration from?

Yeah. My everyday playlist is literally early 2000s music. I even still listen to [music] from the '70s – I just like old music!

My mom is a big influence on a lot of the music that I like. She had me when she was like 19, 20. She's a Cali girl and has great taste in music. I grew up on everything and I feel like a lot of the stuff that I'm doing, you can kind of see that influence.

I grew up on Usher, Cherish, 112, Jagged Edge, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Teena Marie, Luther Vandross and Sam Cooke. Usher was my first concert, ever and actually my last concert — I went to his residency in Vegas with my mom. That's like our thing.

I know you had your hand in many different professions — including barbering and working at a daycare — how did you get into rapping?

I always liked music, but [thought] girl, we need some money right now. Rapping and music is cool, but I always had one foot in and one foot out. When I was [working] my jobs, it was more this is what I need to be doing right now — but I wasn't happy.

It got to a point where I noticed that I was doing all these things, and it worked but it wasn't working for me. I didn't want to get caught up; I didn't want to be stuck doing something just because it works. I wanted to do something that I actually love to do. I decided to quit both jobs because I was literally making me miserable.

I feel like that's what happened with a lot of our parents — they lose focus of their actual goals or what they actually wanted to do, and they get so caught up in what works in the moment. One thing about me, if I don't like something I'm done. I don't care how much money I put into it, if I'm not happy and it doesn’t feed me spiritually and mentally I'm not doing it. Right after [I quit] I was in the studio back-to-back making music. It eventually paid off.

Walk us through your music making process.

A blunt, a little Don Julio Reposado, a space heater because I’m anemic. Eating some tacos and chicken wings or whatever I’m feeling at the moment. It’s not that deep to me, I like to be surrounded by good energy in the studio.

People like to say female rappers aren’t welcoming or don’t like to work with each other. You’re clearly debunking this myth with songs like "Back Outside" featuring Latto and "Splash Brothers'' featuring Karrahbooo. What was it like working with them and how did these collaborations come about?

Karrahbooo and I were already friends before we started rapping. It was harder for people to get us to do music because when we were around each other we weren't like, "Oh we need to do a song together." We had a friendship.

Working with Latto, we didn't collab on that song in the studio. I did the song myself after being really upset at a man. I made the song just venting. I didn't even think that I was ever gonna put that song out, honestly. Latto ended up hitting me up within a week's span just giving me my flowers and telling me she wanted to do a song [together]. I ended up sending her "Back Outside" because I felt like she would eat [it up] and she did just that.

She did! Are there any other female rappers you’d like to work with?

I really want to work with Cardi B — I love her! I'm also looking forward to collaborating with GloRilla.

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

Many female rappers come into the industry and feel like they have to start changing themself to fit a certain aesthetic or archetype. However, everything about you seems super unique — from your voice to your style and appearance. How do you maintain your individuality?

Being yourself is literally the easiest job ever. When you're doing everything you're supposed to be doing, you're being genuine while you're doing it and you’re just being 110 percent authentically yourself — I feel like everything works out for you perfectly fine.

I haven't had the urge to change anything or do anything different. The reason people started liking me was because I was being myself. Even if it wasn't accepted, I'm not going to stop being myself. I do what works for me and I feel like everybody should just do what works for them and not what works for the people outside of them.

That's what creates discomfort for yourself, that’s how you become a depressed artist — trying to please everybody [but] yourself. I feel like people lose sight of that fact. Aside from this being a job or a career for me now, it’s still my outlet and a way I express myself; it's still my form of art. I will never let anybody take that from me. It's intimate for me.

Speaking of intimacy, what was the inspiration behind "Nene’s Prayer"? I want to know who was playing with you.

I was just having a little therapy session in the booth and everyone ended up liking it. Instead of getting mad, flipping out and wanting to go to jail I just put in a song. Even though I said some messed up things in the song, it’s better than me doing those messed up things.

Have you ever written a lyric or song that you felt went too far or was too personal?

Nope. A lot of the [topics] that I [rap about] is just stuff girls really want to say, but don't have the courage to say. But me, I don’t give a damn! If it resonates with you then it does, and if it doesn't — listen to somebody else.

Exactly! What advice would you give to upcoming artists trying to get noticed or have that one song that pops?

If you got something that you want to put out into the world, you just have to have that confidence for yourself, and you have to do it for you and not for other people. I feel like people make music and do certain things for other people. That's why [their song] doesn't do what it needs to do because it’s a perspective of what other people want, rather than doing [a song] that you're comfortable with and what you like.

How do you want people to feel after listening to ‘Princess Pop That?’

I just want the girls, and even the boys, to get in their bag. Regardless of how you went into listening to the album, I want you to leave with just a little bit more self confidence. If you’re feeling low, I want you to feel like "I am that bitch."

It's a no judgment zone. I want everybody to find their purpose, walk in their truth and feel like "that girl" with everything they do. You could even be in a grocery store, I want you to feel like the baddest bitch.

10 Women In African Hip-Hop You Should Know: SGaWD, Nadai Nakai, Sho Madjozi & More

Photo: Screenshot from video

video

Family Matters: How Mike Piacentini’s Family Fuels His Success As His Biggest Champions

Mastering engineer Mike Piacentini shares how his family supported his career, from switching to a music major in college to accompanying him to the GRAMMY ceremony for his Best Immersive Album nomination.

Since Mike Piacentini’s switch from computer science to audio engineering in college, his family has been his biggest champions. So, when he received his nomination for Best Immersive Album for Madison Beer's pop album Silence Between Songs, at the 2024 GRAMMYs, it was a no-brainer to invite his parents and wife.

“He’s always been into music. He had his own band, so [the shift] wasn’t surprising at all,” Piacentini’s mother says in the newest episode of Family Matters. “He’s very talented. I knew one day he would be here. It’s great to see it actually happen.”

In homage to his parents’ support, Piacentini offered to let his father write a short but simple acceptance in case he won: “Thank you, Mom and Dad,” he jokes.

Alongside his blood relatives, Piacentini also had support from his colleague Sean Brennan. "It's a tremendous honor, especially to be here with [Piacentini]. We work day in and day out in the studio," Brennan explains. "He's someone who's always there."

Press play on the video above to learn more about Mike Piacentini's support system, and remember to check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of Family Matters.