Photo: Max Wanger

interview

Chamber Ensemble yMusic Step Into The Light On New LP: "We've Been In Training For This Moment"

Contemporary chamber ensemble yMusic have backed up GRAMMY winners from Paul Simon to John Legend and St. Vincent. On their eponymous new LP, they reveal themselves to be a self-contained universe.

Over the course of a decade and a half, yMusic have pointed their arrow toward collaborators, happy to exist chiefly as facilitators and augmenters — until Paul Simon had something to say about it.

"Every time we'd work with songwriters and bands, they'd say 'So, when are you guys going to write your own stuff?'" the chamber group's violist, Nadia Sirota, recalls to GRAMMY.com. "And we'd be like, 'Oh no, what are you talking about?'"

If you know classical, you'll know this is par for the course. But when yMusic appeared with Simon on his 2018 album of reimagined deep cuts, In the Blue Light, "He was like, 'You guys have to figure out what your voice is as an ensemble yourself,'" Sirota says. "We took him seriously."

With that encouragement from the 16-time GRAMMY winner under their belts, yMusic partitioned time in their rehearsal schedule for writing — and that built a bridge to their autonomous, eponymous new album of originals, which arrived May 5.

YMUSIC places the young sextet — Sirota, flutist/vocalist Alex Sopp, clarinetist Hideaki Aomori, trumpeter CJ Camerieri, violinist Rob Moose, and cellist Gabriel Cabezas — within a concise framework, emphasizing each composition's innate singability and dramatic arc.

"One organizing principle that we kept coming back to was the idea of song form, because that almost felt foreign to our body of work in a cool way," Moose, who has won two golden gramophones, tells GRAMMY.com. "But also, because we've collaborated with songwriters so much, it felt at home to us."

As you absorb YMUSIC's multivalent highlights like "Zebras," "Three Elephants" and "Cloud," read on for an interview with Sirota and Moose about the group's 15-year creative journey, what they bring to the table for singer/songwriters and how this consolidative work came to be.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

The press release for YMUSIC says it finds "the group focused on discovering an artistic voice all their own."

Nadia Sirota: A really important thing to know about the group is that we've been around for 15 years, but every single thing that we've done prior to the album has been a collaboration with another artist.

We have worked with a ton of amazing composers, bands and songwriters, and it's been a joy and a pleasure to work with all those people, but we had never created any original music until we started the process that resulted in this album.

So, it's been really amazing to double down on the creativity within the group. We've always been pretty hands-on in our collaborations with other people — and certainly super-opinionated, and very into editing and honing and re-orchestrating.

The whole time, we had a very creatorly hand, I think, on these collaborations, but we've never really made music ourselves — so that's what this is about.

Was this by design over the past 15 years? To augment other musicians?

Sirota: Yeah, and I think a lot of it, honestly, comes from the fact that we all come from a pretty classical background despite where we ended up in the world. In the classical-music world, it's more common than not that you are either a composer or a performer.

There are some people who do both things in an explicit way, but if you're training as a performer, you're training as an interpreter…. who's working on Brahms and Beethoven and Rebecca Clarke and all that stuff.

Even if you're doing new music, you're working with composers. We took that as we became a young new music ensemble, like so many other new music ensembles.

Rob Moose: I feel like our origin story — our mission from the beginning — was about empowerment.

We were active as freelance performers equally in new classical or classical music, but also in working with songwriters and bands. We had a lot of respect for the groups we were working with outside of classical music, and felt like they were being underrepresented in who was performing their music — or even how they were looking at their collaborative work.

So, I think built into the group's DNA was this idea of helping to — not elevate by our presence, but just lift up these people who were doing great work and give the best possible presentation to it.

We were always interested in underdogs, in a sense, and it just took us a long time to look at ourselves in the same way: Can we help our own voices get out there?

I think we realized that we've been in training for this moment all those years and we're really excited to step into this new role.

Sirota: Another angle of this is that these pieces have really been written collaboratively. It's not like one of us came with a whole bunch of ideas and doled out parts and figured it out.

In the very earliest phases of this, the six of us would get into a room with nothing and just try to create something — and six people is a lot of people to be in that creative space. I think we were all just delighted at how well it worked.

Then the pandemic hit. Everyone had to go our separate ways, but because we had forged this way of working together, we were able to keep that up over digital spaces and figure out how to collaboratively write and hone and record all this stuff.

**I'm most intimately aware of your work on Okkervil River's Away and Paul Simon's In the Blue Light, although I've heard yMusic in any number of other contexts. How do you tailor your approach and methodology to each artist you work with?**

Moose: I think each collaborator we've worked with has really set a tone for the way in which we'll approach the results we're looking for.

Ben Folds and Bruce Hornsby were two really important people for us that helped us get off the page and encouraged us to do the homework and create the parts — but also find freedom in live shows, or in recording studios, to create in a less conventional way for us.

Paul Simon did too, but also, he was the most meticulous about editing and refining the ideas. Which makes sense, because if you look at his work — his words, the stories, the structures of what he's created, the interaction with different styles and cultures of music — I think thoroughness is something you would never imagine would be a missing ingredient there. I feel in some ways, he pushed us to be in the moment, but also be the most under the microscope.

I think our group always approaches collaborations the same way: with great seriousness and joy and admiration for who we're working with. We take cues from the people we're working with about what's going to work best for them, as well as their audience.

Sirota: We've learned to be adaptable to all different processes, whether it's from audio first or chords first or written notation or just a vibe.

Sometimes, when I'm trying to create something alone, I get mired in my critical brain and it's really hard to work. I think the cool thing about the systems yMusic has built to work with is that they don't start from a critical place — although we get super-critical.

Moose: Being there's so many people in the group, one of the benefits is that we're still able to observe each other and pull ideas out of each other like those collaborators did for us.

A lot of pieces of music that we composed for the record started with almost eavesdropping on our neighbors as they were warming up, like: "What was that sound you just made? What is that technique that you're doing?" We would be able to shine a light on somebody else's idea that they might consider completely insignificant and perfunctory, not the basis of a composition.

To be able to bear witness to that and encourage it, that's something we learned from our collaborators; they helped us see that in ourselves, and I think we also helped them find things in that way. So, we've been really excited to keep that as part of our process.

As the violist and violinist in yMusic, how would you two characterize your interplay and function as cogs in the musical machine — both between you two and the ensemble as a whole?

Sirota: I feel like there's definitely a certain amount of rhythm viola that I sometimes play in the group. There are our most obvious functions, and then our auxiliary functions.

In the group, the only tools we have as a bassline are the cello and bass clarinet, really. So, there are ways in which those guys really end up functioning that way, and then sometimes, we totally subvert that.

The broadest spectrum of the group is piccolo to bass clarinet, kind of. Sometimes, we use that spread to kick it up a little bit. If we want to add some energy, we'll either pull something up or pull something down in a really nice way.

Being a violist is a funny thing, because you're always adding butter to the sauce. You're not necessarily the main thought of it, there's a way in which you can really add an unctuousness to the sound. Usually, I'm just trying to add a little bit of texture and excitement.

Sometimes, Rob and I are in the stratosphere doing light disco string lines or whatever. There's all sorts of flexibility in the way that this group works. Sometimes, we throw viola over to the wind side and have flute and violin do string things. There are really so many different options with the group.

I don't know if you know this, but the [template of] instrumentation that we have hasn't existed before. So, we have had the great luxury of trying to figure out every single thing that it can do, and there's some neat stuff.

Sometimes, the cello is up in the violin and viola range, too, so we have this crazy high-string section for the violin section, but made up of things that are in that register, with timbres that are slightly more exciting, in my mind.

Moose: I think, in some ways, the role that you have, Nadia, is maybe the most diverse in the group.

With cello, you can form that core low-string, warmth, support thing. Then, some of my favorite combinations are when we pair bass clarinet with viola and horn for that warm triadic lifestyle. Then, like you pointed out, you'll be doing high stuff in octaves or unison with me.

Sometimes, two or three of us can represent what the guitar or piano would do. I do love being on this bright team, sometimes, with trumpet and flute. Part of my journey has been to learn how to attempt to mimic the way their notes end, which is so abrupt compared to the way our notes end.

*yMusic. Photo: Max Wanger*

What were the core ideas that dictated the framework of YMUSIC?

Moose: We didn't start with an intention to write a record, necessarily. It was more of a commitment to figure out what would happen if the six of us, 13 years into our journey, decided to collaboratively compose in real time with no cheat sheets, no prep, no collaborators.

Sirota: Anything can inspire the beginning of something, and then the material itself dictates where it ends up having to go. Oftentimes, we set out to do something that was not where we ended up, but it brought us somewhere else that was really cool. I think that's the nature of writing.

YMUSIC really breathes as a listening experience; it's sequenced rather well, in my opinion, and the drama seems to expand and retract.

Sirota: That was certainly the goal, and I will say we had a lot of material for this album. Pulling it together in a way that felt both exciting and kind to the listener was the goal.

The thing about the six of us is we can get in this hyper twin-language thing where we keep wanting to gild the lily, and keep on wanting to work. We could probably obsessively rewrite every single one of these songs until we die, if we wanted to.

Moose: We have pieces in there that felt like anchors that you want to arrive at in different moments, like "Baragon," "The Wolf" and "Three Elephants" — the structural beams that are [tracks] one, four and seven.

I think it felt important to end with the piece "Cloud" — the last piece that we worked together on in the room before the pandemic started. The idea of that piece was to try to introduce something positive and soothing and nurturing in a moment of uncertainty.

Sirota: Interestingly, "Baragon" is one of the most recent things that we wrote. So, we bookended the album with these two works that were important for us in the process of writing, and figured out a way to get from point A to point B.

As 2023 rolls on, what's in the works for yMusic, and what would you like to eventually do?

Moose: We got to play the entire record for the first time at Carnegie Hall in January, which was really exciting.

I know we're really looking forward to presenting the work more — especially the concert that we did — the first half being music we composed, and then the second half being two premieres from two composers that we really admire.

I think it's important] to hear our work alongside work like that, and not separate them and be like, We did that before, we're doing this now, but be like, All of these things are who we are.

Sirota: We've got some upcoming collaborations we can't quite talk about yet. So, there's the stuff on the songwriter side that will be percolating.

The stuff on the composer side that we can talk about is: we're excited to record this brand-new major work by Andrew Norman soon, and a new piece by Gabriela Smith coming in the next season or so. Alongside this, we're going to carve out more time to write more stuff.

A neat thing about this group, which has always been true, is it's not the only thing that any one of us is supposed to do. We have always treated it like an extremely important part of our lives, but we all also do other creative things, and they're not all in the same realm at all.

So, I feel like a nice thing is that when we do come together, we're always coming with a fresh perspective.

Yo-Yo Ma On His Lifelong Friendships, Music's Connection To Nature & His New Audible Original, Beginner's Mind

photo_gallery

The Oral History Of Alabama Shakes' Sound & Color

58th GRAMMY nominees Brittany Howard, Shawn Everett, Blake Mills, and others tell the inside story of the Album Of The Year-nominated Sound & Color

Alabama Shakes' Boys & Girls was among the most soulful and celebrated debuts of 2012, yet few anticipated the degree to which frontwoman Brittany Howard and her Southern cohorts would up the ante on Sound & Color. The band's evolution earned four 58th GRAMMY nominations, including Album Of The Year and Best Alternative Music Album.

With a spacious and evocative sound that defies genre barriers, Alabama Shakes' Sound & Color was written and recorded over the course of a year, during which time Howard would hole up in her basement with a stash of granola bars for 12-hour songwriting marathons. Most of the songs were recorded during four two-week sessions at Sound Emporium in Nashville, Tenn., followed by a final recording and mixing session at Ocean Way Recording in Los Angeles. The process included recording furnace vibrations, therapeutic coloring books and escaping into a world of one's own creativity.

Following, Howard and other key participants behind the chart-topping collection give the inside story of Alabama Shakes' Sound & Color.

Brittany Howard (artist/co-producer): Instead of saying this record is really, really different, I would just say it's more evolved. Recording a Boys & Girls Part 2 would have been really boring for me. We'd had plenty of time to learn more, to learn different types of music, and of course our tastes are always growing. So this record was half looking forward and half looking back. It was like, "I've always wanted to do this. I've always wanted a vibraphone, I've always wanted to arrange a string section." But I can only play a few instruments, so when I was doing a demo for a song like "Gemini," everything was on keyboards. And then we'd go into the studio and have to figure out how to map that across the band.

Shawn Everett (engineer/mixer): I always loved "Gemini" a lot. In the initial demo Brittany had this insane digital harmony on her voice and it made her sound like a god. She already sounds like a god, so it was like a god times two. We tried to approximate that effect in our version as well. I also love the crazy guitar that keeps appearing out of nowhere on that song.

Blake Mills (co-producer): Generally the band felt that their wide range of influences weren’t necessarily making their way into their own music. Their sound previous to this record felt like an attempt to capture the live sound of the band, like you might approach recording an orchestra. Many of the records they love don't sound like a recording of an artist's rehearsal, but rather an attempt to transport their listeners to a world of their own making.

Howard: I was definitely making it up as I went along. I was like, "OK, there's four days before we go into the studio. How many songs do I have ready?" Sometimes it'd be two and sometimes it'd be none. And that's when I'd go down to my basement and just keep writing songs without taking a break. I've worked on [my basement] a lot, but there's still a bat that lives in there, and there's a little mouse family. So I wasn't lonely.

Rob Moose (string arranger): The main challenge we faced was to not make [the album] feel like "Alabama Shakes plus strings." The idea was certainly not to have bells and whistles, or something that just sounds expensive, or even to play a huge role in the emotional expression of the record, as strings can do. It was really "detail work" that we wanted to do, and I'm proud of some of the touches, especially the ones that most listeners wouldn't know are strings.

Everett: In addition to Rob Moose's incredible string parts, there are several moments in which you think you're hearing strings but it's actually furnace vibrations or other strange acoustic sounds rattling. The individual frequencies have been melted and distorted into sounding like a string section or some other otherworldly texture.

Howard: When you're in the studio, you might be listening to someone hit a snare drum for about an hour and a half. So while that's going on, we're doing coloring books — you know, adult coloring books, not children's coloring, not The Lion King — and we're doing art, and we'll sit in the lounge writing country songs. And sometimes, before the session would start, we'd go in there and record country songs. Then Blake would come in and we'd be, "OK, back to work!"

Mario Hugo (art designer/video producer): The label had me come in and listen to the new music, and I was taken by it right away. It was very visual, enigmatic and spacey, but also honest and raw. And challenging as well. I listened to the final mixes through the entire design process, which is exceedingly rare. I can say that Sound & Color was, musically, one of my favorite albums to work on.

Mills: I think it's very unusual these days to find a majorly successful band who can be this fearless in challenging their audience. We dumbed nothing down, no one seemed to second guess their convictions and their fans have really stepped up to the plate and supported that bravery.

Moose: The band had some friends visiting the studio and they cooked a southern feast, which was actually amazing. I've never seen home-cooked food in the studio, and the vibe that day kind of summed up the soulful, down-to-earth qualities of the band for me.

Howard: We're just a normal group of people who believe in writing and making something. And honestly, it was truly from a point of having fun. It wasn't to get famous or anything like that. We wanted to play gigs, that was our goal, but we didn't have anywhere to gig. So it's crazy now that we're nominated for [an Album Of The Year] GRAMMY. It's remarkable and really divine, I think. But we also worked really, really hard to get here. And I won't let something like this make me relax.

Bill Forman is a writer and music editor for the Colorado Springs Independent and the former publications director for The Recording Academy.

Tune in to the 58th Annual GRAMMY Awards live from Staples Center in Los Angeles on Monday, Feb. 15 at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT on CBS.

Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images

list

Inside Neil Young & Crazy Horse's 'F##IN' UP': Where All 9 Songs Came From

Two-time GRAMMY winner and 28-time nominee Neil Young is back with 'F##IN' UP,' another album of re-recorded oldies, this time with Crazy Horse. But if that sounds like old hat, this is Young — and the script is flipped yet again.

Neil Young has never stopped writing songs, but for almost a decade, he's been stringing together old songs like paper lanterns, and observing how their hues harmonize.

2016's Earth, where live performances of ecologically themed songs were interspersed with animal and nature sounds, was certainly one of his most bizarre. 2018's Paradox, a soundtrack to said experimental film with wife/collaborator Darryl Hannah, took a similarly off-kilter tack.

He's played it straight for others. Homegrown and Chrome Dreams were recorded in the ‘70s, then shelved, and stripped for parts. Both were finally released in their original forms over the past few years; while most of the songs were familiar, it was fascinating envisioning an alternate Neil timeline where they were properly released.

Last year's Before and After — likely recorded live on a recent West Coast solo tour — was less a collection of oldies than a spyglass into his consciousness: this is how Young thinks of these decades-old songs at 78.

Now, we have F##IN' UP, recorded at a secret show in Toronto with the current version of Crazy Horse. (That's decades-long auxiliary Horseman Nils Lofgren, or recent one Micah Nelson on second guitar, with bassist Billy Talbot and drummer Ralph Molina from the original lineup.)

Every song's been christened an informal new title, drawn from the lyrics; the effect is of turning over a mossy rock to reveal its smooth, untouched inverse.

It's named after a fan favorite from 1990's Ragged Glory; in fact, all of its songs stem from that back-to-the-garage reset album. Of course, that's how they relate; they're drawn from a single source. But Young being Young, it's not that simple: some of these nine songs have had a long, strange journey to F##IN' UP.

Before you see Neil and the Horse on tour across the U.S., here's the breakdown.

"City Life" ("Country Home")

The Horse bolts out of the gate with "Country Home," from Ragged Glory; in 2002's Shakey, Young biographer Jimmy McDonough characterized it as "a tribute to the [Broken Arrow] ranch that is surely one of Young's most euphoric songs."

As McDonough points out, it dates back to the '70s, around the Zuma period. With spring sprung, another go-round of this wooly, bucolic rocker feels right on time.

"Feels Like a Railroad (River Of Pride)" ("White Line")

Like "Country Home," "White Line" also dates back to the mid-'70s — but we've gotten to hear the original version, as released on 2020's (via-1974-and-'75) Homegrown.

The original was an aching acoustic duet with the Band's Robbie Robertson; when the Horse kicks it in the ass, it's just as powerful. (As for Homegrown, it was shelved in favor of the funereal classic Tonight's the Night.)

"Heart Of Steel" ("F##in' Up")

As with almost every Horse jam out there, the title track to F##IN' UP defies analysis. Think of a reverse car wash: the uglier and grungier the Horse renders this song, the more beautiful it is.

"Broken Circle" ("Over and Over")

Title-wise, it’s excusable if you mix this one up with "Round and Round," a round-robin deep cut from the first Neil and the Horse album, 1969's Everybody Knows This is Nowhere. Rather, this is yet another sturdy, loping rocker from Ragged Glory.

"Valley of Hearts" ("Love to Burn")

As McDonough points out in Shakey, "Love to Burn" has an acrid, accusatory edge that might slot it next to "Stupid Girl" in the pantheon of Neil's Mad At An Ex jams: "Where you takin' my kid / Why'd you ruin my life?"

But the chorus salves the burn: "You better take your chance on love / You got to let your guard down."

"She Moves Me" ("Farmer John")

The only non-Young original on F##IN' UP speaks to his lifelong inspiration from Black R&B music — a flavor OG guitarist Danny Whitten brought to the Horse, and has persisted in their sound decades after his tragic death.

Don "Sugarcane" Harris and Dewey Terry wrote "Farmer John" for their duo Don and Dewey; it dates back to Young's pre-Buffalo Springfield surf-band the Squires.

"Not much of a tune, but we made it happen," Bill Edmundson, who drummed with the band for a time, said in Shakey. "We kept that song goin' for 10 minutes. People just never wanted it to end." Sound familiar?

"Walkin' in My Place (Road of Tears)" ("Mansion on the Hill")

"Mansion on the Hill" was one of two singles from Ragged Glory; "Over and Over" was the other.

While it's mostly just another Ragged Glory rocker with tossed-off, goofy lyrics, Young clearly felt something potent stirring within its DNA; back in the early '90s, he stripped it down for acoustic guitar on the Harvest Moon tour.

"To Follow One's Own Dream" ("Days That Used To Be")

Briefly called "Letter to Bob," "Days That Used to Be" is Dylanesque in every way — from its circular, folkloric melody to its shimmering, multidimensional lyrics.

"But possessions and concession are not often what they seem/ They drag you down and load you down in disguise of security" could be yanked straight from Blonde on Blonde.

For more of Young's thoughts on Bob Dylan, consult "Twisted Road," from his 2012 masterpiece with the Horse, Psychedelic Pill. "Poetry rolling off his tongue/ Like Hank Williams chewing bubble gum," he sings, sounding like a still-awestruck fan rather than a peer.

"A Chance On Love" ("Love and Only Love")

Possibly the most resonant song on Ragged Glory — and, by extension, F##IN' UP — "Love and Only Love" is like the final boss of the album, where Young battles hate and division with Old Black as his battleaxe.

(Also see: Psychedelic Pill's "Walk Like a Giant," where Young violently squares up with the '60s dream.)

The 15-minute workout (which feels like Ramones brevity in Horse Time) It's a fitting end to F##IN' UP. There will be more Young soon. A lot more, his team promises. But although his output is a firehose, take it under advisement to savor every last drop.

Inside Neil Young's Before and After: Where All 13 Songs Came From

Photo: Julie Vincent

interview

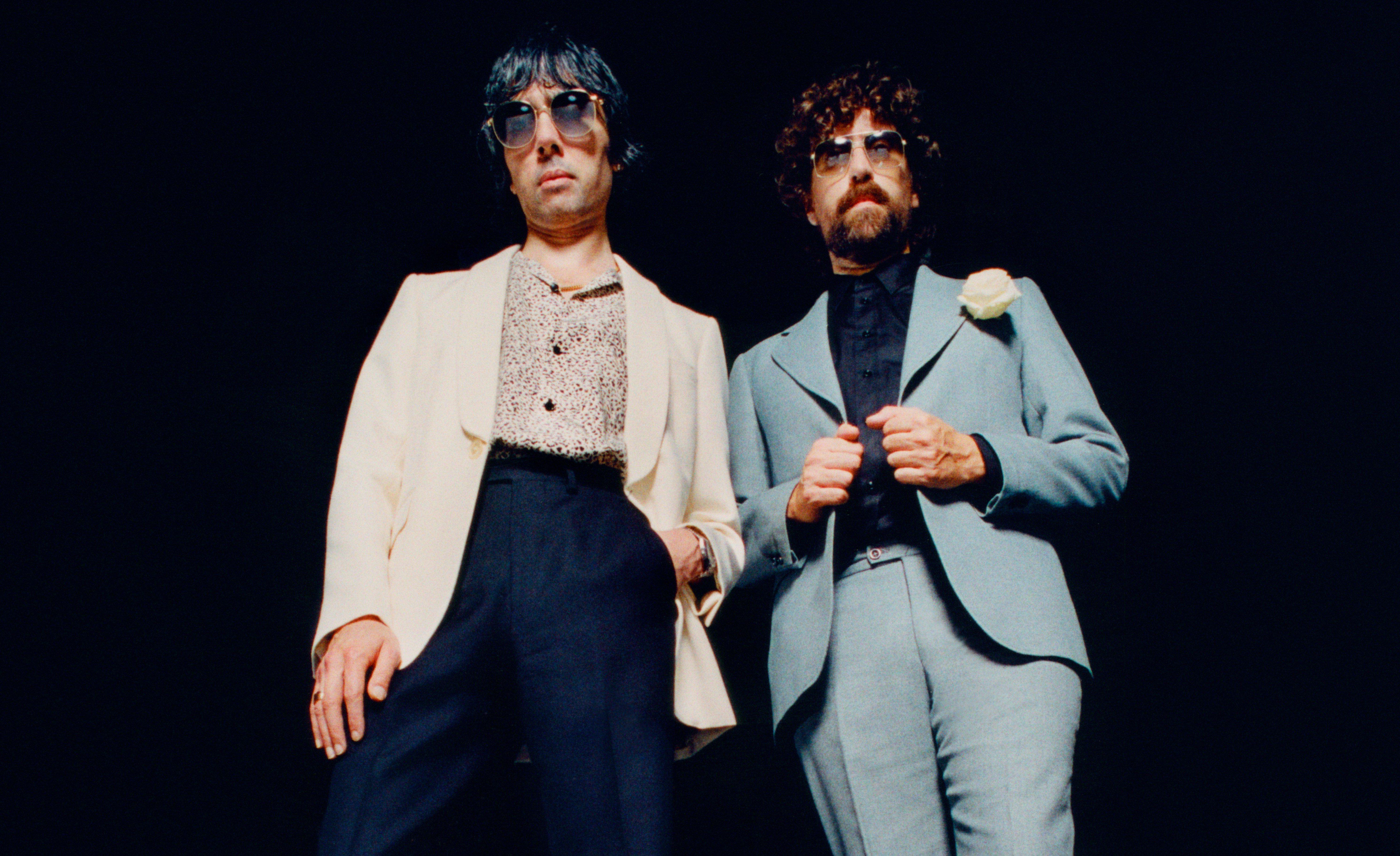

Justice On Creating New Album 'Hyperdrama': "We'll Always Try To Make Everything Sound A Bit Like A Space Odyssey"

"Every time we go back to the studio, we start a bit from zero again, mainly because we try to get rid of old habits every time we start something new," Justice's Xavier de Rosnay says of creating their fourth studio album, 'Hyperdrama.'

GRAMMY-winning French electro duo Justice have always moved to the tune of their own drum machine.

Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay's debut release, 2003's "We Are Your Friends," was a radical reimagining of a tune from experimental psych-rock group Simian. Originally a remix made for a Parisian college radio contest, "We Are Your Friends" didn't win, but grabbed the attention of Daft Punk's manager Pedro Winter, who had just founded his impactful indie dance label Ed Banger Records. The track eventually became an anthem of the bloghouse era.

Response to their second single — 2005's glitchy, fuzzy "Waters of Nazareth" — nearly made them reconsider their decision to switch careers from graphic design to electronic music. Two years later, the duo had another major hit — along with their first GRAMMY nominations and some international chart success — with their third single, "D.A.N.C.E.", a joyous bop sung by a youth chorus.

While their core influences of disco, electro, funk and psych rock remain, Justice is not interested in rehashing the same sounds. They are interested in making you feel, and the sounds that get them the most excited in the studio are the strange and boundary-pushing ones.

They're beloved for their high-production live show, where they mashup and reimagine their biggest tunes into a frenzy of sound and lights. They debuted a new live show at Coachella 2024, which features a dizzying new light contraption created over 18 months by their long-time lightning designer Vincent Lérisson. After each studio album, they produce a live album from the subsequent tour, a costly and time-consuming project which they recently told Billboard nearly bankrupts them every time. Yet their last, 2018's Woman Worldwide, won a GRAMMY award for Best Dance/Electronic Album.

Justice is just as meticulous in the studio. For their first studio album in eight years, Hyperdrama, (out on April 26 on Ed Banger/Because Music), they created hundreds of versions of each track and spent an extra year on the album stitching the best parts together. While they've produced for and remixed plenty of big names over the years, the new album is their first to feature recognizable stars like Tame Impala, Miguel and Thundercat, along with Rimon, Connan Mockasin and the Flints.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Xavier de Rosnay to dive deep into the creation of Hyperdrama, the album's new collabs, Justice's new live show, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

How were your performances at Coachella?

It was good. It was only the second show of the tour. And the beginning of the tool is generally where there's a lot of space for improvement. We could definitely feel that we did better [on weekend 2] than the week before because we were a bit more relaxed, a bit more accustomed to the stage setup and to what we used to conduct the music and everything. Everything felt more fluid. But there can be a difference between what we feel and how the crowd feels, and that's impossible for us to say.

How did you envision this new live show and what are you excited about bringing it around the world?

The way we envision it is as has been the same since the beginning, it's just now we have access to a larger array of technologies to be able to do that. We've always liked the idea of instead of hiding the technical aspects of the stage, enhancing them in every way possible. Everything you see on stage at the beginning [of the show] is stuff that is very mechanical, technical and that are meant to be on stage. As it evolves, everything is moving and lit up.

We hope that there's a lot of moments where the audience can actually get lost [in the moment] and not fully understand what's happening on stage because of the way things are lit. We know the matrix of the stage in and out, but sometimes we see things we don't really understand because it creates a dimensional space that is difficult to comprehend at times. For us, that's the best, it's when we have kind of magic moments.

And musically, same thing, it's always the same as from the beginning but better, freer, bigger. Justice live is Justice's greatest hits; we're not the kind of band that won't play the hits and will force feed the weird [tracks]. For us, it has to be a big party, it has to be fun from top to bottom. Although it's only our fourth album, now we feel we have enough of a catalog to make something that is relentless and fun from the beginning to the end.

I definitely feel a cinematic journey on the new album, is that intentional? And what's the story you're trying to tell with Hyperdrama?

Well, it's intentional in the way that the most powerful music is music that brings images to the mind. Classical pieces of music, like Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, are the biggest hits ever and they have no drums, no beats, no lyrics. But they've been the biggest hits for centuries because they have a very powerful, evocative strength. For us, music is first and foremost meant to reveal this. So we never make music with the idea that it has to be for dancing or pop or anything, we always make music to try to convey powerful emotions. Although we didn't work with a theme like cinematic in our mind, we're happy to hear that some listeners are feeling that way.

The way the album is structured is very classic in the sense that it's structured like a lot of narrative forms. The beginning of the record, let's say the first third, is setting the tone and feeling at home. After our first album, we entertained the idea of starting every album with the theme of "Genesis," a bit like when you go to the cinema and hear the 20th century theme.

You feel good for three, four songs, you go on cruise control and then things start to drift a bit. For [Hyperdrama], that's "Moonlight Rendez-Vous" and "Explorer" — when things start to turn wrong a bit and, and then you go into a sort of vortex, like on "Muscle Memory," "Harpy Dream." In a film, that would be when the goofy sidekick of the protagonist dies. At that moment, you think everything is at its worst, then you have the final drop with "Saturnine" and "The End," which is a bit like the homecoming and happy ending situation — you're back at home again and hopefully you end on a positive note.

Is it kind of a Justice Space Odyssey?

Yeah, totally. I think for as long as we make music, we'll always try to make everything sound a bit like a space odyssey. It's funny that you mentioned space odyssey because [Hyperdrama] has four different sections that are very distinct. That's something that we love too — connecting things that don't really make sense at first glance.

Within some tracks, for example "Incognito," we're going from this almost psychedelic funk intro, and then you have a straight cut and you're in the future, everything is electronic. Things don't really make sense at first, but you listen to it and you get used to [this kind of transition].

And that was something where we really worked on a lot on this album, to make those different universes coexist and sometimes in a not very peaceful way. It can be a bit off-putting at first listen, but that's what's great with the record. You can feel it's a bit strange and you return to it and hopefully you start getting used to these kinds of things until they become almost natural.

The two of us have been working closely for a long time, so getting surprised and sometimes getting a bit unsettled is really what we're looking for in the studio. Generally, when we start to track and we're having a laugh because we are feeling we're going too far, it's something we've haven't done before, or we're making something ridiculous, that's a very good sign. These are typically the things we're looking for when we write a track or produce a song.

"Incognito" feels very classic Justice, although you've said Travis Scott's "Sicko Mode" kind of inspired its shifts. How did "Incognito" come together and how did it shake up your songwriting process?

I think the "Sicko Mode" thing is getting a bit bigger than what it is. It was not like we had an epiphany hearing that song. We think it's a great track, but for us, it was more of a reminder that it's always possible in any context to approach things in a very naïve way in a sense, and that it's possible to escape the canon of classical structures and classical writing and still achieve something that is surprising and free and that is legible for a vast amount of people. The principle of juxtaposing things that are foreign next to each other is not new, but to see it on such a big song always gives us a lot of hope about music in general.

"Incognito," "One Night/All Night," "Generator," "Afterimage" and "Dear Alan" all work a bit on that principle that we had where we recorded several versions of the same track, of the same riff separately. For "Incognito," we had a plan of the song very precisely from the demo. But when we produced it, we recorded the intro and outro, that was one track that we mixed and produced separately. All the electronic parts were another track, all the disco parts in the middle were another. We produced and mixed them separately and only during mastering, we brought them back together. We really wanted to feel like it was separate songs that we'd put together.

Would you say you are perfectionists?

No, because there is no such thing as perfection. For us, the best we can do is make something that we feel good about, and this is when we know it's done. It's not perfection because we're not looking to make something that checks all the boxes of what perfection should be.

Most of the music that we listen to is not perfect to any extent. But for us, it's perfect when it's faithful to the original feeling and idea we had when we started putting those songs together.

I've been really obsessed with "One Night/All Night." What was it like working with Tame Impala's Kevin Parker, and how did you find that mesh between your sounds?

We didn't think of "One Night/All Night" as a song with vocals at first. We played [the demo] for Kevin and he was like, "I can hear something in that one." His vocal topline really adds some sort of weird sadness and melancholy to the track. The main riff is so simple, I think the simplest we've ever made, the dun dun dun. That's what is great with collaborating, a topline can very much shape a song. We fell in love with that new emotion that he brought to the song.

We really wanted to sound like we had found an unused Kevin Parker song, and sampled it and made a futuristic song with it. So we re-recorded the disco parts; it's almost like the disco part in the middle was the original record and what's before and after is the modernized version of it. And in the intro, his voice is in a key that is a bit off-putting. It builds up slowly and when the first chorus hits, you have his real voice that is instantly recognizable and very powerful and everything comes together — it's a beautiful moment to us.

It was really fun working with him. I mean, it was fun working with everyone [on Hyperdrama]. We almost felt like a mouse in a hole just looking out at things; you get to see everybody's idiosyncrasies and the way they think about music.

Why did you want to make a sonic tribute to Alan Braxe on "Dear Alan"?

It's more of an inside joke than anything, but in the realm of electronic music, he's been an inspiration for us from the beginning. He's always had this kind of melancholic thing to his music that a lot of other bands from the French Touch first wave don't really have. For us, the French Touch first wave is more like shiny club music that's very euphoric. Alan Braxe was always a bit less dance-y but a bit more melancholic and elegant in a way, and that touches us a lot more than straight dance music.

We also love his persona. The guy has been releasing maybe one song every three years for the past 20 years. This guy is even less productive than we are. But every time he puts one song out, it's always a gem, it's perfect. I don't think he's ever released one bad track.

The track is based on the sample of "Dear Brian" by Chris Rainbow. Chris Rainbow is a musician from the '70s and '80s that was doing post-Beach Boys music and "Dear Brian" was to Brian Wilson. For a long time, the working name of our track was "Dear Brian" and when we had to give it a proper name, we were like, Okay, the vocal sample reminds us of Alan Braxe, let's call it Dear Alan. It's a way for us to pay tribute to Alan Braxe and also Chris Rainbow.

When you think back to 2007 and "D.A.N.C.E." and having that kind of fast success on a global scale, what memories remain for you from that early era of Justice?

The truth is that it was not fast. There were four years between the moment we started the band and "D.A.N.C.E." and our first album came out. It was four years of doubts and thinking we were doing artistic suicide, for real. All those tracks took a lot of time to actually reach an audience.

In the meantime, we did our first commercial suicide with "Waters of Nazareth" in 2005. We felt really bad about that track for a couple of months because we had no positive feedback about it. When we would play at festivals, as soon as the song would start, the technical people from the festival would run on stage to see if everything was plugged in correctly. Finally, a year after, it started to reach the underground, people more coming from rock music that felt there was something cool about it.

Once that was settled, we released "D.A.N.C.E." which was not at all what people wanted us to make, because that was a disco track with a kid singing on it. It took some months, but then it made [an impact]. Then we made "Stress" and had a huge backlash on the video.

Our first album sold a lot of units, but it was over the course of maybe two years. It was really at the end of 2008, beginning of 2009 that it had reached its kind of cruise speed. So, retrospectively, it looks a bit like we came out of nowhere and found a spot for us, but it was made over five, six years; it was a proper development in a way.

How do you feel you've grown as individuals and as producers since that early Justice era?

We didn't grow up too much, to be honest. Every time we go back to the studio, we start a bit from zero again, mainly because we try to get rid of old habits every time we start something new. We also change the instruments that we use. The first months of Hyperdrama were really almost like R&D. We were trying to find new ways of making sounds. We didn't produce much music then, we were just trying things and getting accustomed to the new setup. We learn everything as we're making a record and especially on this one. We also wanted to get rid of all habits we have in terms of writing and producing.

To us, knowledge, a lot of times, can be the enemy of the good. We're trying to find the good balance between, of course, using what we've learned throughout the years to make things that get better hopefully with time and at the same time not to get stuck into patterns that can make you feel old. We're very aware that we're entering a phase of being an old band in a lot of ways.

We really hope that Hyperdrama does not translate as an old record made by an old band. Hopefully it still sounds fresh and naive and playful, as if it was a record from a young man.

Chromeo On Their New Album 'Adult Contemporary,' Taking Risks And 30 Years Of Friendship

Photo: Courtesy of Brann Dailor

video

Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?: Mastodon’s Brann Dailor Shares The Story Of Their Best Metal Performance Track, “Sultan’s Curse”

Mastodon drummer and singer Brann Dailor reveals the metaphor behind the track that snagged him his first golden gramophone, “Sultan’s Curse,” and how winning a GRAMMY was the “American Dream” of his career.

Mastodon's drummer and singer Brann Dailor assures you he did not purchase his shiny golden gramophone at his local shopping mall.

“I won that! I’m telling you. It’s a major award,” he says in the latest episode of Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?

The metal musician won his first GRAMMY award for Best Metal Performance for Mastodon's “Sultan’s Curse” at the 2018 GRAMMYs.

“‘Sultan’s Curse’ was the jumping-off point for the whole theme of the album,” he explains. “The protagonist is walking alone in the desert, and the elements have been cursed by a Sultan.”

It’s a metaphor for illness — during the creation of the album, the band’s guitarist Bill Kelliher’s mother had been diagnosed with a brain tumor and bassist Troy Sanders’s wife was battling breast cancer.

For the band, the GRAMMY award represented their version of the American Dream and culmination of their career work. Even if Mastodon didn’t win the award, Dailor was happy to be in the room: “We felt like we weren't supposed to be there in the first place! But it's an incredible moment when they actually read your name."

Press play on the video above to learn the complete story behind Brann Dailor's award for Best Metal Performance, and check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of Where Do You Keep Your GRAMMY?