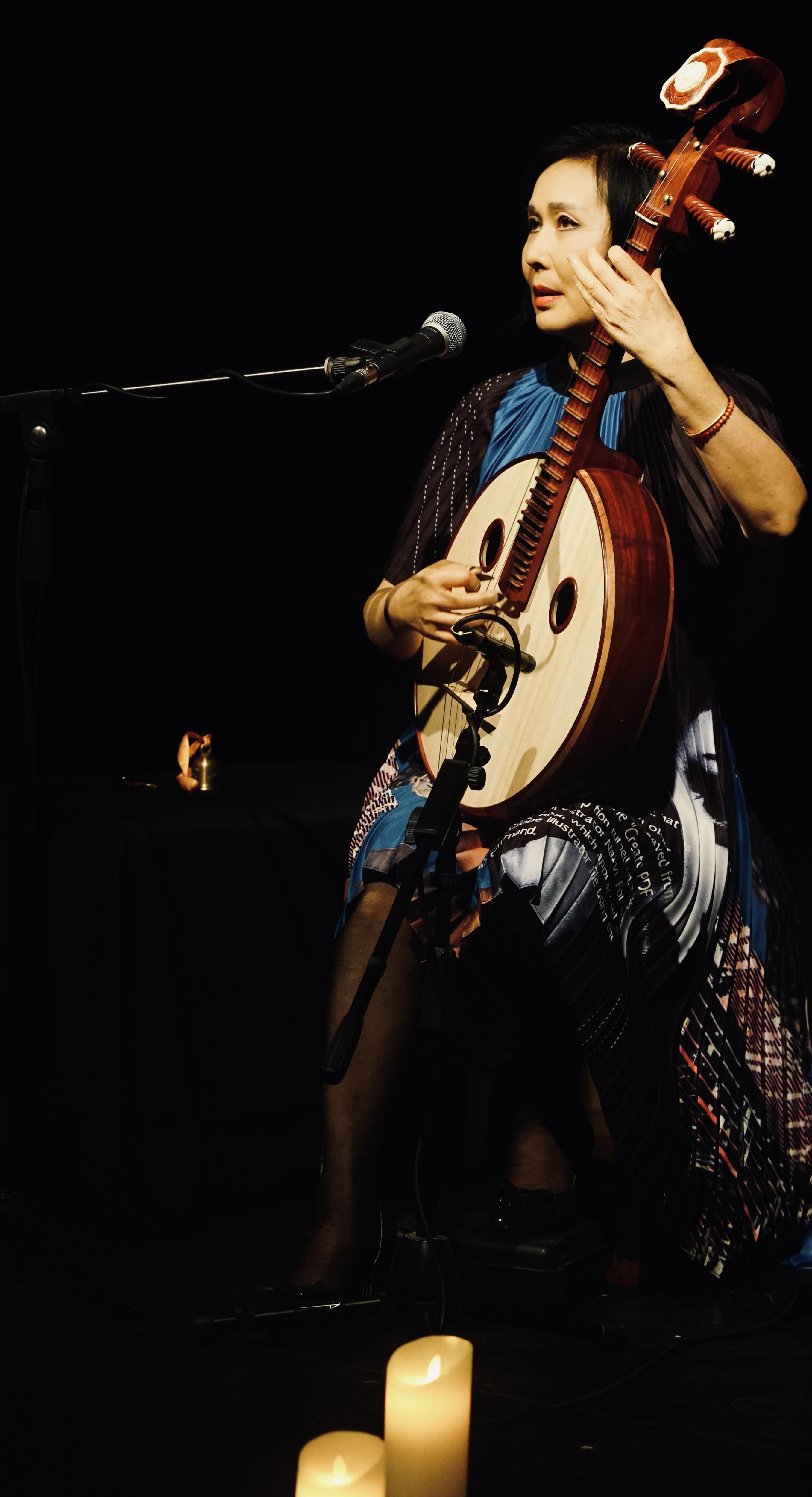

Photo: Jiang Bingqing

Min Xiao-Fen

news

Pipa Master Min Xiao-Fen On The "Harmony And Balance" Of Traditional Chinese Music & Her New Album, 'White Lotus'

To Min Xiao-Fen, the music of the West and East aren't so different. And although "Anicca," off her new album, 'White Lotus,' has an otherworldly quality, a closer listen evokes a universal sensation of integrity and order

To hear Min Xiao-Fen's "Annica," named after a Buddhist term meaning "impermanence," is to feel pulled between the earth and the ether. She plays the pipa, which, in America, is typically thought of as a Chinese lute. The tonality of the strings may evoke something close to an acoustic guitar, but the harmonies have depth and darkness beyond description—to say nothing of her droning, rasping vocal over the top.

But after a minute or two, gravity sets in. The tune, premiering exclusively on GRAMMY.com, from her new album White Lotus, out June 25, reveals ancient dimensions of harmony and order. (The pipa's been around for more than 2,000 years, after all.) What initially may have come off as strange and different becomes incontrovertibly human—something from the heart or the guts. In conversation, Xiao-Fen is kind, bubbly and informative, and she's quick to note that American sounds aren't so different from those ringing from China.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//EzKHa3gVjUM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

"Blues and bluegrass reminds me of what I studied in China!" she says with a dash of mirth. "Talking blues reminds me of a Chinese [form] called pingtan. It's music from the Southeast that I grew up with."

Speaking of transdisciplinary connections without borders, here's another: The relationship between music and cinema. White Lotus is Xiao-Fen's original score to the long-lost 1934 Chinese silent film, The Goddess. The music isn't just played on pipa, but on a variety of other plucked instruments—plus, eerie loops mixed with Buddhist chanting. The results sound far more familiar than alien thanks to Xiao-Fen's mastery and deep connections to American improvisational music.

GRAMMY.com caught up with Min Xiao-Fen to talk about her roots in traditional Chinese music, how she came to score The Goddess, and how music can explode cultural barriers between the East and the West.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity from two conversations.

Tell me about the pipa's history and significance in China.

The pipa developed during the Qin Dynasty between 220 and 270 B.C. Of course, it's a plucked instrument. Western people say it's a Chinese lute. It's a pear-shaped wooden body. The name "pipa" comes from Chinese syllables: pi and pa. The maker of the instrument played it and heard sounds like "Pi-pa, pi-pa," so he kept the name. The most common technique is to use your first finger, strike down, and with your thumb, strike back, so it sounds like "pi-pa."

The pipa has four strings. The tonality is A-D-E-A. During the Tang Dynasty from 618 to 907 A.D., a pear-shaped wooden body pipa was introduced to China from Central Asia. At that time, the pipa only had three or five frets, was held horizontally and they used a plectrum. During the Tang Dynasty, the pipa became a principal musical instrument in the imperial court, and it was played solo or with an orchestra.

Right now, I'm playing the modern, reformed pipa, so it's chromatic-scaled and has six large frets and 24 bamboo frets. It's been around so long that it has a large repertoire; [it can be] played lyrical-style, martial-style. It's a wonderful instrument, especially for solo.

What feelings is it meant to convey? Is it meant to capture the entire spectrum of emotions? Or does it have a specific role in that regard?

Chinese music is always associated with nature and seeking that harmony and balance. When we play traditional music, which is very hard because you have to use your inner energy, we always emphasize strong but not aggressive, soft but not weak. This is how I was trained as a traditional Chinese musician. You have to be very careful how you play, with your energy. Just don't show too much! Always the balance.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//iuDE7qnFQRk' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

How did you come to this instrument?

I grew up in a musical family. My father—he passed away—was an educator and pipa master. He taught at Nanjing University for 60 years! My sister was a well-known erhu player; that's a Chinese two-string fiddle. She passed away, too. I'm the youngest. My brother is an orchestra conductor.

When I was young, I just wanted to play. I didn't want to study music. My father always encouraged me to study a Chinese instrument, but I was just not into it. One day, I remember my father, after university, came back home and said, "Hey, your classmate wants to study pipa with me!" I lent her the pipa and immediately got jealous. So I told my father, "I want to learn!" I was 10 years old.

Is the pipa the only traditional instrument you play on White Lotus?

I played several other plucking instruments. Actually, it's a whole family of instruments. One is the ruan. It's also a plucked instrument, four strings. It's kind of a lower tone, like a viola, a little bit. Also, I play the sanxian. It's also in the Chinese plucked-instrument family. The sanxian has three strings and no frets with a long handle. Also, the guqin, one of the ancient seven-stringed instruments. We're going back 3,000 years.

Tell me about scoring The Goddess.

I had to compose a musical theme for each character in the film. For the single young mother forced to work as a prostitute, struggling to support her young son, I used Buddhist chanting and voice with electronic loops to surround her and to show her lotus-like purity.

For her young son, I created some simple notes to emphasize his innocence. The sounds for the thug, or gangster, who was stealing money from a woman trying to save money for her son's education, are dark, ugly and irregular. The climax of the film occurs when the young mother grabs a bottle and smashes the thug on his head. That moment is so strong, so I decided to simply use silence and let the action speak.

Min Xiao-Fen. Photo: Jiang Yu

Where do traditional Chinese music and American improvisational music connect for you?

I was a pure traditional musician, and I have a lot of stories I could tell you about how I went in this direction. Basically, I learned all kinds of genres and styles of jazz on stage, because I work with so many great musicians. I started composing my music in 2012 with my Dim Sum CD. I was thinking, "I want to do something for myself." Just spontaneous. I thought I would start to improvise on swing notes and see how it goes.

Is there a way that understanding the ancient musical heritage of Asian-Americans can help combat xenophobia?

That's what I want to do. I feel like it's my duty. I want to introduce not only my instrument, but all kinds of things, arts and film. America's a great place for all kinds of races and cultures.

First of all, I feel very lucky because I never thought I could go that far. I was totally trained as a traditional musician, not changing the notes, just following what the master taught me. Coming to America, I felt very lucky. I met so many musicians that influenced me. I could become myself. Before, I was so stiff! When I came to America, everyone just said, "Hey, do what you want to do! Be yourself!" I fundamentally changed.

It's not only films. I also worked with dancers and opera singers. Also, visual arts. I learned so much from different kinds of formats and arts. It's good to share your experience and share your culture—to tell people what a great history China has.

I feel like when one views another fearfully as an interloper, understanding that they have their own rich traditions and inner lives just like them can help soothe those pains. I mean, China is an ancient place; America is only about 250 years old.

You know, there are a lot of similarities. Blues and bluegrass remind me of what I studied in China! Talking blues reminds me of a Chinese [form] called pingtan. It's music from the Southeast that I grew up with. It's a form of singing and talking and making jokes and playing and acting. It's very similar to the blues. This world is small, you know? People should be open-minded.

We think these lands are so far-flung, but they're not. The East and the West aren't on different planets.

You don't know this instrument, but music is a universal language. You don't need to say something. You just play it and make them happy.

Tomoko Omura On The Universality Of Japanese Folktales & Her New Album, Branches Vol. 2

Photo: SM Entertainment

interview

K-Pop Group RIIZE Detail Every Track On New Compilation 'RIIZING – The 1st Mini Album'

In an interview, the rising K-pop boy group discuss the creative process behind each track on their brand new EP — including the album's new song, "Boom Boom Bass."

While RIIZE might be a more recent addition to the K-pop scene, you wouldn’t be able to tell.

RIIZE took the industry by storm last September with their debut single "Get A Guitar." The catchy, retro-synth pop song sold over a million copies in the first week of its release.

From their debut in 2023, RIIZE was determined to carve out a space for themselves in the expansive K-pop landscape by performing "emo pop" — emotional ballads that still manage to be danceable, evoking the sounds of older gen groups like Got 7 and Super Junior — while also experimenting with other genres. The brightly alluring "Love 119" and disco whirlwind "Talk Saxy" allowed RIIZE to continue their ascent, and netted the group Favorite New Artist and Rookie Of The Year honors at multiple Korean award ceremonies last year.

On June 17, they'll release RIIZING - The 1st Mini Album. The compilation record features all of the rookie group's releases plus an additional song "Boom Boom Bass," and demonstrates their versatility and willingness to experiment with genres. With their output compiled, it's easy to see that RIIZE's youthful energy and distinct personalities truly shine.

Learn more: 11 Rookie K-Pop Acts To Know In 2024: NCT Wish, RIIZE, Kiss Of Life & More

"We wanted to reflect on how far we’ve come from our debut days and growing as artists," Anton tells GRAMMY.com over a video call from L.A. "[The album is] a culmination of our journey and experiences as young adults who are pursuing their dreams."

It’s clear that RIIZE are enjoying the ride they're on together. They laugh at each other's jokes and finish each other's sentences, demonstrating that there's deep friendship behind their already tight harmonious connection. The group is in the midst of an international fan-con tour that runs through the summer — an experience that will, likely, deepen their already close bond.

In an interview, RIIZE’s Sungchan, Anton, Wonbin, Sohee, Eunseok and Shotaro offer a track-by-track breakdown of RIIZING - The 1st Mini Album, including the creative process behind each song, how they keep themselves motivated, and their musical dreams for the future.

"Siren" is your pre-debut song and was one of your most anticipated releases. Can you share a bit about the creation process and how it felt to release this song to the world?

Shotaro: We have a lot of fond memories when we think of "Siren" as it reminds us of our trainee days. We recorded the song while we were still rookies and shot the video in L.A. I remember being in the studio and encouraging each other to give our best deep voices to make our voices shine.

Eunseok: I think a large part of why people like "Siren" so much is the rhythmic drum beats and soft piano riffs that creates this high rush vibe. The chorus is my favorite, and was the most fun to sing as it’s very addictive to sing along to.

Your most recent song, "Impossible" is a house track about being determined and never giving up. Were you nervous at all venturing into a new genre?

Anton: Growth and youth is a huge part of our music, and that’s something we sought to achieve with "Impossible." House music is a genre that is not usually seen in K-pop, but this is something we wanted to experiment with. So we learned firsthand from long-time house music creatives and input their suggestions into the recording. It was a new experience that allowed us to deep dive into a genre we wouldn’t normally be familiar with.

Sohee: The recording was a little difficult at first, because the vocal keys were a bit higher than our usual pitch. But I feel like we successfully encapsulated the genre very well.

Your new song — the special addition to the EP — is called "Boom Boom Bass." It's a disco-influenced track about playing bass guitar; does anyone in RIIZE have experience playing that instrument?

Wonbin: We do have experience playing the bass guitar. Getting to recreate those moments in the studio was awesome, and you can hear the excitement in our voices. The song also showcases a totally different side of us that fans haven’t seen before: it’s disco but funk and still pop.

"Love 119" is one of your most successful songs. Can you take me back to the day you recorded it?

Sungchan: "Love 119" captures the feeling of falling in love for the first time in a dreamy and melancholic manner. We decided to recreate that in the studio and put a lot of our emotions into it by channeling good energy.

Wonbin: The song samples a beloved Korean song, "Emergency Room," released by the band called IZI in 2005. The song captures the distinct charm of emotional pop, offering a different appeal compared to "Get A Guitar," "Memories," and "Talk Saxy."

Shotaro: We aimed to create choreography that many people could follow. While brainstorming in the practice room with Wonbin, he and I came up with dance moves like the "1-1-9" gesture, that you see in the video. The song has a really bright vibe, making it fun for us to perform.

Can you detail the creative process behind "Talk Saxy"?

Sohee: We started creating "Talk Saxy" right after performing at KCON L.A. in July last year and we learned the choreography almost immediately.

We wanted to embody a more confident and breezy sound but still within our niche genre of emotional pop. It took a few weeks of practice to get the perfect take and I think the song helped expand our musical sound by a large mile.

Read more: 9 Thrilling Moments From KCON 2023 L.A.: Stray Kids, RIIZE, Taemin & More

One of your more recent singles, "9 Days," focuses on your journey as a band. Did you find yourselves feeling nostalgic in the studio?

Sungchan: "9 days" has a more natural feel because while we were making the song, we had to reference back to our trainee days in practice. The lyrics are a very detailed description of our trainee days and who we were before debuting.

Anton: I would say we had a fun time in the studio because it felt like we were finally telling our story ourselves and being able to share that with our fans is the best.

"Honestly" reminisces about past love. What, or who, were you thinking about while recording it?

Wonbin: I think we really aimed to capture the theme of putting yourself first and saying a final goodbye to someone you thought the world of. That resonates throughout the song, especially in the lyrics. It’s an emo pop ballad at its core.

"One Kiss" was RIIZE's first foray into emo pop and sets you apart from other groups as you highlight your vulnerability. How did you go about finding that sound?

Anton: I see "One Kiss" as a song made with our fans in mind, we had a hands on approach with making the video as we wanted it to come from our hearts.

Sohee: I would not say we have found our sound yet as we are still growing and experimenting. We hope to create more good songs like "One Kiss" in the future.

You’re in the midst of a fan-con tour, what has been your favorite city to tour so far?

Shotaro: We love every city equally, we started off in Korea and felt right at home. In Japan, we had so much eye contact with the crowd as they were very hands on. Previously, in Mexico, the crowd's energy was infectious and awesome.

What are your plans for the second half of this year?

Sungchan: We plan on finishing off our fan-con tour by the end of August. Our fans can expect to see us at end of the year award shows with bigger and better performances from last year.

11 Rookie K-Pop Acts To Know In 2024: NCT Wish, RIIZE, Kiss Of Life & More

Photo: James Baxter

interview

On 'AG! Calling,' Atarashii Gakko! Declare That Youth Is Never Lost — No Matter Your Age

"Our concept is for everyone. It does not depend on how old you are as long as you're living and enjoying the moment," Atarashii Gakko!'s Kanon says of the group's raucous new album.

As is with most legends, there are different accounts of how the members of Atarashii Gakko! met.

Some say they met in a supermarket aisle when they all reached for the last pack of discounted sushi, others say they’d known each other as kids. Yet others claim that the hallowed halls of their to-be-company Asobisystem were hard at work to rescue humanity. Whatever the story, the wheels of fate were turning to put together a foursome poised to fight the invisible but omnipresent monster of boring, soulless adult life — armed only in their sailor uniforms and chock full of sizzling energy.

Dramatic retelling aside, the quartet — Suzuka, Rin, Kanon and Mizyu — might not be battling titanic fictional villains, but they are up against an equally fearsome foe: boredom. Their recently-released album, AG! Calling, reinforces the quartet’s image as a paragon of fresh, zany energy that sends a shock through sluggish veins. AG! Calling is an escape from the drudgery of the everyday, and Atarashii Gakko! believe it's their "destiny" to spread the joy of seishun (youth) to the world.

Slotting in perfectly with the group’s core ethos, the "calling" in AG! Calling is taken from the Japanese kanji "Korin," which has a dual meaning of descending, as well as one’s own calling. On their single "Tokyo Calling" — released seven months ago and now included on the album — the group descends upon the concrete metropolitan facade of Tokyo, with Mizyu’s characteristic helicopter ponytails swinging full speed. The group makes an urgent announcement: "Don’t hesitate to move forward! Hope for the future is here!" They repeat this mantra and call forth a ball of light from the sky, leading everyone from mundanity to freedom.

It’s a proverbial full-circle moment for the group, who heralded themselves as the "Youth Representatives of Japan" — their name in Japanese is Atarashii Gakko no Leaders, or New School Leaders — and championed finding and embracing your individuality in the face of a highly conformist society. Early releases like "Mayoeba Totoshi (If You Get Lost)" confronted listeners with hard-hitting questions: "What is the meaning of freedom? If it’s just acting like an adult, I disagree. Let me find it myself." The eerie and relentless "Dokubana" (2017) bemoaned the fate of an outlier in society, which is "scorned and hated" until it withers in place.

By the time they got to "Nainainai" — their first release under 88Rising — the group had condensed their ethos into pointed critique wrapped in effervescent eccentricity, representing the unique worldview that the biggest rejection of conformity would be to boldly embrace who you are without rejecting the confines of society outright. With a decidedly '90s-inspired hip-hop sound, the track veered from calling out the pressure students face in school to being miffed about being a late bloomer. Their calling card was their retro-inspired school uniforms, a sound that couldn’t be shoved into a pigeonhole if one tried, and energetic dance moves inspired by Kumitaisou, Japanese gymnastics symbolized by pyramids, which became an extension of the profound feelings on their songs.

As they have expanded their world — marked by performances on "Jimmy Kimmel Live!," a successful debut at Coachella this year and performance at Primavera Sound in Barcelona — and inched further into adulthood, "seishun" has evolved from a philosophy to a way of life. AG! Calling rejoices in its reinvention of everyday tedium and positions them firmly as the cheerleaders of a liberated way of life.

Below, Atarashii Gakko! talk about AG! Calling, their successful Coachella performance, and how their core philosophy will develop with them.

You guys just came off of a very successful Coachella set. How was the entire experience?

Suzuka: We have been together as a group for nine years, and the show at Coachella was like, Ah, that was why we had to be together, we had to form the group The live performance was the answer of the meaning of being together as Atarashii Gakko! That's the kind of feeling we had.

Suzuka, you actually said in an interview earlier this year that participating in Coachella will bring you one step closer to Beyoncé. Once you wrapped up the performance, did you feel that way?

Suzuka: [Jumps up and flashes a thumbs up.] Yes! I took one step towards Beyoncé!

Rin, you got the chance to meet Lauryn Hill, whom you have cited as an inspiration and an idol. Do you want to share how Lauryn Hill has inspired you?

Rin: My father is a hip-hop fan, so when I was a child, I had already started listening to hip-hop music and Lauryn Hill. And then during [our] last U.S. tour, we — because she was playing in L.A. for her 25th anniversary — went to see her live, and I bought a t-shirt and everything!

And this time at Coachella, we knew that YG Marley, her son, was going to be playing but we didn't know that she was going to be there! So, I was thinking, like, maybe we'd have a chance to see her or whatever.

But then I accidentally saw her — she had finished the stage and she came out – and I was like Ahhh; I was shaking! She was very... mother-like, and like "Oh, thank you!", and she was smiling and she took a photo! The first time I saw her I was like Oh yes, she's real! She exist!' I was very happy she treated me like a mother.

Speaking of mother, you guys were also featured on Japanese musical icon Sheena Ringo's album recently. She had lovely things to say about you in an interview, particularly that she was "overwhelmed" working with you guys. She called you "reliable" and "dazzling" — that's a glowing recommendation from such an icon.

Suzuka: We're so happy! Of course, she's very big and we are very overwhelmed and thinking [that the collaboration was] the result of not changing our style and not taking the easy way out! We think it's the result of nine years of effort, and we're so happy that she said that.

Let's come to 'AG! Calling.' When you guys first started singing about "seishun," you were treating it as something light, something you guys were having fun with. But in this album, you're calling it your destiny, which has a finality and weight to it. Can you describe the evolution of this concept?

Rin: This is not like a result of getting somewhere. From the initial stage, we've had seishun as a philosophy, and we were having fun and enjoying the moment. Rather than being a final point, AG! Calling [represents] our nine-year trajectory: all our experiences of having fun, receiving and giving the power [of youth]. It's like a resumé: this is Atarashii Gakko!, and this is our power. This is us now. From this point, we will keep moving forward. That's what we want people to see. That's why we're flying and floating [on the album visuals].

On your early releases, your songs talked about problems that teens and high school students have. But now, you've grown into adulthood. How has the concept of "seishun" evolved in this aspect?

Suzuka: That's also a coincidence because "Nainainai" was kind of like our first record [under 88Rising] — like a presentation of what we were. We were teenagers too. We were more fresh, we were younger, we were going to school and everything. But now we're facing the world. We are speaking to more people, not only teenagers, so we wanted to focus on the world [going] from a child to an adult. Maybe it was just the right timing.

How do you think this concept will evolve with you guys over time? Youth isn't something that stays with us forever.

Kanon: In the first place, the "youth" that we were conveying had nothing to do with age. Maybe you think that "seishun" is only for teenagers, but our concept is for everyone. It does not depend on how old you are as long as you're living and enjoying the moment.

Now that we're adults, we still have [seishun] because we're putting in all our efforts to live and enjoy to the maximum. Whatever the age, if people can enjoy the moment, that's seishun. That's the philosophy we've had from the beginning, so we haven't changed anything about that concept.

What was the development of this album like? Where did you guys primarily work on this?

Rin: We began last summer with "Tokyo Calling."

Suzuka: I don't know exactly how long it was, because we’ve been bringing demos to LA for about two years. It's all mixed, because there were some demos that we didn't put in the last [album]. So we were like, 'Maybe we can change this song a little bit, we can release that one, can remix an old one or compose new ones." So, it's a mix - some are older, and some are new.

Mizyu: We don’t make demos for [specifically] this album or that record. We keep making trials and demos with our producers in LA and Japan, and maybe [the songs] can be on an album, but our style is always looking for new songs.

I noticed that a lot of imagery on this album was inspired by heroes. When you performed "Tokyo Calling" on Jimmy Kimmel, the outfits were inspired by Ultraman. There are tracks like "Superhuman" or "Hero Show". What was the reason behind this?

Mizyu: It's true that we are kind of like superheroes [in terms of] the performance and the uniforms. Maybe from our name as well – Atarashii Gakko no Leaders – you already get the ‘superhero’ vibe because we are trying to just have fun, but we are also helping you if you're sad or tired. We are giving you power. We are helping you, so "Superhuman" and "Hero Show" are the results of that.

You collaborated with MILLI on the song "Drama." How did that happen? Had you heard her music before?

Rin: Actually, "Drama" was kind of an old song we recorded by ourselves in LA a few years ago. We had this in stock for quite a long time. We were thinking of releasing it with maybe like a plus [factor] or something extra, so that's why we decided on the collaboration with MILLI. We didn't actually record with her, but for us the [final] song is still a fresh creation. But maybe in the future, we can get the chance to sing together or collaborate. There's more possibilities in the future.

Let’s discuss "Forever Sisters," which focuses on your bond, especially in context of how much you have grown over the past few years. Did you feel like it was important to remind yourself of your relationship with each other?

Suzuka: "Forever Sisters" is a very important song for us, because we made this song when we were visiting L.A. and working with Money Mark, and we kept working on it online [between] Japan and L.A. It's very special to us, so when we were thinking about the songs we wanted to put on the album, all four of us agreed that this song has to be on AG! Calling.

And also the message — we are more than friends, more than family. Our relationship is very special and very important. It's beyond anything [I can explain]. So this song had to be on AG! Calling, because we're starting a new journey going global.

Money Mark is a longtime collaborator for you guys, along with yonkey. In some ways, some of these people were there as you were establishing your signature sound. So as you expanded globally, did you have conversations with them about how you wanted to develop your sound?

Suzuka: Yes, we always keep having these kinds of conversations all the time. And from "OTONABLUE," our Japanese team with Yoshio Tamamura — they have a lot of knowledge about the music and what they want to show as Japanese culture, what they want people to perceive as Japan. [Songs like] "Omakase" and "Toryanse" understand that very well.

We keep having those conversations. The energy that the four of us have and how to go from this point on, they understand that and give us the sound, and we record it and put our lives into it. It's always a good session.

You guys will celebrate your 10th anniversary next year. Any special plans?

Suzuka: We still don't have the details of the 10th anniversary actually, because we are living in the present. We're thinking about this year's concerts, but for sure, we will have something big. Maybe [when] we're reaching the time when we start our 10th year, but right now we're not thinking about it.

Sometimes, for your shows, you write Shuji calligraphy on paper and stick it all over the venue. In a video in 2021, you did one such exercise where Rin wrote the Kanji for "Dream," Kanon wrote "Diligence," Mizyu wrote "Take a relaxing break," and Suzuka wrote "Life." If you had to do the same exercise again, what would you write?

Suzuka: [To be honest] We're not sure what we wrote! Right now, if we had to write something, we're not very sure [of that either]. Maybe today, we write one kanji and tomorrow, it might change. That's the reality. We're not very sure what Kanji we will write individually.

Rin: But [if we had to write something] as Atarashii Gakko!, we're very sure about that. The other day, in an event, we put up a big Shuji [calligraphy], like four meters by six meters, which we put together and we wrote AG! Calling. The word "calling" was written using the kanji for "Korin" in Japanese – that was very suitable, and very real as a group from us. So, as a group, we can say AG! Calling is what we will write.

10 Neo J-Pop Artists Breaking The Mold In 2024: Fujii Kaze, Kenshi Yonezu & Others

Photo: Christopher Caldwell

news

Blues Music Awards 2024 and Blues Hall Of Fame Inductee Ceremony Honor the Past, Present, & Future Of The Blues

The Blues Music Awards kicked off several days of events honoring the genre's legacy, which included the Blues Hall of Fame Inductee ceremony and the opening of an innovative new exhibit at the Blues Hall of Fame featuring a hologram of Taj Mahal.

It was a big week for music in Memphis. The 45th annual Blues Music Awards, a top honor in the genre, were handed out on Thursday, May 9, in Memphis, Tenn. in a ceremony sponsored by the Recording Academy. The awards were the capstone to several days of blues-related events, including the annual Blues Hall of Fame induction ceremony the day before.

An audience of approximately 1,000 — including industry professionals, fans, and some of the genre's biggest artists — packed the grand main exhibit hall of the recently renovated Renasant Convention Center for the BMAs banquet, produced by the Memphis-based Blues Foundation. With 25 awards and more than a dozen performances, the awards show, hosted by broadcast veteran Tavis Smiley, often felt more like a homecoming than an industry event.

Read below for four key takeaways from this year's Blues Music Awards and Blue Hall of Fame Ceremony.

Mississippi's Blues Roots Remain Strong

Located right next to Memphis, Mississippi is home to one of the country's four GRAMMY Museums and is widely regarded as one of the birthplaces — if not the birthplace — of the blues. The state has nurtured some of the genre's greatest talents, including Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and B.B. King. The Magnolia State's deep connection to the blues was evident during the awards, with Mississippi mainstays and GRAMMY winners Bobby Rush and Christone "Kingfish" Ingram among the top winners.

Despite a 65-year age difference, Rush and Ingram share a deep devotion to the blues. At 90 years old, Rush, an incredibly spry chitlin' circuit road warrior who has re-emerged in recent years as perhaps one the blues' biggest stars, won Best Soul Blues Album for All My Love for You and his second B.B. King Entertainer of the Year award. Ingram, only 25 years old and already a GRAMMY winner for Best Contemporary Blues Album in 2022, was the night's top winner, taking home four awards: Album of the Year and Contemporary Blues Album of the Year for Live in London, Contemporary Blues Male Artist, and Instrumentalist-Guitar.

Other multiple award winners included another artist originally from Mississippi, 79-year-old Chicago guitarist John Primer, who won Traditional Blues Male Artist and Traditional Blues Album for Teardrops for Magic Slim, and Texas' Ruthie Foster, who captured top vocalist honors and won Song of the Year for "What Kind Of Fool," co-written with Hadden Sayers and Scottie Miller.

The Blues Need To Be Seen To Be Heard

Though the BMAs largely honor recorded works, the show itself emphasized that the blues are a genre best experienced live. The ceremony, which ran about four hours (historically on the shorter side for this event), was packed full of performances, most running longer than your typical awards show slots.

Highlights included the opening set by emerging artist nominee Candice Ivory, who performed selections from her BMA-nominated album When the Levee Breaks: The Music of Memphis Minnie, backed by keyboardist Ben Levin and guitarist William Lee Ellis, who also played songs from his album Ghost Hymns, a nominee for Best Acoustic Album.

Another Mississippi artist, powerhouse bandleader Castro Coleman, known as Mr. Sipp, who has one GRAMMY nomination and an appearance on a GRAMMY-winning Count Basie Orchestra album, brought the crowd to their feet early with his gospel-fueled segment. To cement his Best Guitarist win, Ingram delivered a blistering performance with his band, wading into the audience for one of his beautifully precise, soaring solos.

There was so much music to be heard that it spilled out into the streets. Most nights following BMA-related events, fans and fellow artists could be found in the clubs on Beale Street, the famous Home of the Blues, for showcases and impromptu jam sessions. These were highlighted by the 10th annual Down In the Basement fundraiser for the Blues Foundation on Wednesday. Organized and hosted by Big Llou Johnson, a blues musician and host of Sirius XM's B.B. King's Bluesville channel, the show featured appearances by Mr. Sipp, GRAMMY nominees Southern Avenue, and more.

Honoring The Blues' Past

Among the other events that made up BMA week was the Blues Hall of Fame Induction ceremony, held on May 8 at Memphis' Cannon Center for the Performing Arts before a crowd of about 200, including past inductees Bobby Rush and Taj Mahal. Hosted by artists Gaye Adegbalola (Saffire — the Uppity Blues Women), GRAMMY winner Dom Flemons (Carolina Chocolate Drops), and veteran blues radio deejay Bill Wax, the observance saw the induction of seven artists, five blues singles, one album, a book, and a blues academic into the Hall of Fame.

Highlights from the evening included Alligator Records head Bruce Iglauer's humor-filled induction of Chicago house stompers Lil' Ed & the Blues Imperials in the performers category; the heartfelt introduction of the late folk singer Odetta by her friend Maria Muldaur and the emotional acceptance by Odetta's daughter, Michelle Esrick; and former National Endowment for the Humanities chairman William R. Ferris, inducted as a non-performer, delivering a circuitous-but-engrossing recounting of his life documenting blues music and culture.

Bringing The Blues To Life

Taj Mahal stands in front of the exhibit featuring his own hologram. | Photo: Kimberly Horton

One of the non-award related highlights of the week was the opening of a new exhibit at the Blues Foundation's Blues Hall of Fame, also on May 8, which introduced a high-tech element to the down-home genre. Musician Taj Mahal was on hand the day before for the unveiling of a cutting-edge AI-powered hologram of himself that acts as a virtual tour guide for the Half of Fame, allowing visitors to interact with the blues great.

This hologram, only the second exhibit of its kind in America (the first is in the Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame in Boston), uses Holobox, a new technology from Holoconnects, to render a life-like image that can answer questions, talk about exhibits, and play instruments. Taj Mahal, who had to sit and talk for several hours for the technology to scan his likeness and voice, is the first artist to receive the virtual treatment from the Blues Foundation. Bobby Rush and Keb' Mo' are expected to be added later.

Explore the full list of 2024 BMA winners below to celebrate the artists keeping the blues alive and discover who took home the top honors this year.

2024 BMA Winners

B.B. King Entertainer of the Year

Bobby Rush

Album of the Year

Live In London, Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Band of the Year

Nick Moss Band

Song of the Year

"What Kind Of Fool," written by Ruthie Foster, Hadden Sayers & Scottie Miller

Best Emerging Artist Album

The Right Man, D.K. Harrell

Acoustic Blues Album

Raw Blues 1, Doug MacLeod

Blues Rock Album

Blood Brothers, Mike Zito/ Albert Castiglia

Contemporary Blues Album

Live In London, Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Soul Blues Album

All My Love For You, Bobby Rush

Traditional Blues Album

Teardrops for Magic Slim, John Primer

Acoustic Blues Artist

Keb' Mo'

Blues Rock Artist

Mike Zito

Contemporary Blues Female Artist

Danielle Nicole

Contemporary Blues Male Artist

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Soul Blues Female Artist

Annika Chambers

Soul Blues Male Artist

John Nemeth

Traditional Blues Female Artist (Koko Taylor Award)

Sue Foley

Traditional Blues Male Artist

John Primer

Instrumentalist – Bass

Bob Stroger

Instrumentalist – Drums

Kenny "Beedy Eyes" Smith

Instrumentalist – Guitarist

Christone "Kingfish" Ingram

Instrumentalist – Harmonica

Jason Ricci

Instrumentalist – Horn

Vanessa Collier

Instrumentalist – Piano (Pinetop Perkins Award)

Kenny "Blues Boss" Wayne

Instrumentalist – Vocals

Ruthie Foster

Washington D.C. Chapter Dinner & Conversation Answers "Can We Have Rhythm Without the Blues?"

Photos: ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images; Robin L Marshall/Getty Images; Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images; Disney/PictureGroup; Sam Morris/Getty Images

list

10 Exciting AAPI Artists To Know In 2024: Audrey English, Emily Vu, Zhu & Others

In honor of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, get to know 10 up-and-coming AAPI artists — including Alex Ritchie, Curtis Waters and others — whose music spans geography and genre.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) have made strides in the music industry for many years. Every year, more AAPIs enter executive roles in the industry, increasing their visibility and impact.

Artists in the Asian and Pacific Islander diaspora — including Silk Sonic (Bruno Mars and Anderson.Paak), Olivia Rodrigo, and H.E.R. — have graced the stage and won golden gramophones at Music's Biggest Night. During 2024 GRAMMY Week, the Recording Academy collaborated with Gold House and Pacific Bridge Arts Foundation to create the Gold Music Alliance, a program designed to foster meaningful connections and elevate the impact of Pan-Asian members and allies within the Academy and wider music industry.

Yet, AAPI groups are significantly underrepresented in the music industry. Pacific Islanders are often forgotten when it comes to lists and industry due to their smaller percentage in the population.

Despite the lack of representation, social media and streaming platforms have introduced fans to new and rising artists such as Chinese American pop singer Amber Liu, Japanese American singer/songwriter Mitski, and Hawaiian native Iam Tongi. Others are showcasing their sound on the festival circuit, as San Francisco-based indie rocker Tanukichan and Korean American guitarist NoSo did at last year's Outside Lands festival. With AAPI-led music festivals, such as 88 Rising’s Head in the Clouds and Pacific Feats Festival, artists in this community are given opportunities to exhibit their talent and, often, their heritage.

For many emerging artists, a like, reshare, or subscribe can help them gain the attention of mainstream studios and bolster tour attendance. So, in honor of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, check out these 10 up-and-coming AAPI artists performing everything from pop to soulful R&B and EDM.

Alex Aiono

Maori-Samoan American singer Alex Aiono moved to Los Angeles from Phoenix at 14 to pursue a music career. After going viral for his mashup of Drake's "One Dance" and Nicky Jam’s "Hasta el Amanecer," Aiono now has over 5.73 million YouTube subscribers. He was then cast in several popular films and television series, including Netflix’s Finding Ohana, Disney Channel’s "Doogie Kameāloha, M.D.," and "Pretty Little Liars: Original Sin."

But, for the 28-year-old R&B/pop singer, music has always been his calling. Aiono released several singles and, in 2020, a full-length album, The Gospel at 23. Inspired by his experience in Hollywood and his relationship with his religion (as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), The Gospel at 23 plays on the simplicity of a piano, drums, tambourine, and a choir, beautifully fusing modern soul with the old-fashioned gospel. Since then, the artist has released tender medleys – with his most recent heartbreaking single "Best of Me."

"I view this as a very, very lucky life that I get to express myself and that's my job," he told AZ Central. "My quote-unquote job."

Alex Ritchie

L.A.-based singer/songwriter Alex Ritchie has been honest about her journey as a queer mixed-Asian woman in the industry. The Filipino-Japanese-Spanish artist said she was constantly overlooked or told she wouldn’t be commercial enough in the American music industry.

"I’m the only musician in my family, and I came from a family of humble means; so even though I had conviction in what I wanted from a young age, it wasn’t realistic," Ritchie told GRAMMY.com in 2019. said. "Pursuing something like entertainment was so risky. I couldn’t afford to fail. We couldn’t afford to dream like that. BUT I had unrealistic dreams anyway, and after my first gig at the Whisky I knew that was it."

Ritchie has been thriving in the industry, becoming the youngest sitting committee member in the history of the Recording Academy’s Los Angeles Chapter, advocating for LGBTQ+ and Asian American representation in music. After her experience with GRAMMYU in 2019, the alternative rock singer released 404 EP and several sultry singles, including a melodious and fervent love song, "Blueprint," released this January. Ritchie plans on releasing more music and on her terms.

"Time and people have finally caught up with the vision that I always had for myself, even if they didn’t see it before," Ritchie tells the Recording Academy. "One of the things I’m most proudest of is that I never really changed. I’ve stayed exactly who I am to the core. I think when you do that and when you realize there’s no one else like you, you become the most powerful person in the room."

Audrey English

**You may not have heard of Audrey English, but you have heard her music on "America’s Got Talent," "American Idol," and Netflix’s "Love Is Blind." Her songs are featured on the shows during the most prominent moments of the contestants’ lives on screen: In "AGT" and "American Idol," English’s rendition of "Lean On Me" played during golden buzzer moments and emotional arcs; er song "Mama Said" went viral after being played during Ad and Clay’s wedding scene in season 6 of "Love Is Blind."

Inspired by Etta James, Nina Simone, and Amy Winehouse, the Samoan American artist swoons audiences with her soulful, powerful tone with songs that focus on relationships, empowerment, and love. English also showcases her culture in her videos; in the music video for her harrowing ballad "Happy," English featured the beauty of Samoa alongside a Samoan romantic love interest. She hopes one day to write a Samoan song.

In her latest single "Unapologetic," released on April 25, English wrote the song as an anthem for others to live without shame. "In a world where we are so influenced by others, social media, and being our own worst critics - sometimes we need to take a step back to realize it all doesn’t really matter," English wrote on Instagram. "Regardless of your beliefs, background, and passions, this is a call to be authentically you, however, you define that!"

Brooke Alexx

**Brooke Alexx’s bubblegum pop personality is infectious, and her catchy hooks, including her latest pop-rock single, "Hot Like You," are fit for everyone’s summer playlist.

Alexx has never shied away from revealing intimate parts of her life. The Japanese American artist writes her music from her experiences as the oldest child, being best friends with her exes’ moms, and her connection to her Asian roots.

In her 2022 gentle ballad, "I’m Sorry, Tokyo," Alexx reveals the shame she once felt for not wanting to learn about her Japanese heritage, as well as the guilt she feels for never learning the language and culture. "There’s so much about the culture that I don’t know and missed out on that would be so cool to be a part of my life now," Alexx told Mixed Asian Media. "So, I’m trying to return to those roots a little bit these days."

She is now making up for lost time. Alexx embraces her Japanese heritage and will visit the country with a select group of fans.

Curtis Waters

Curtis Waters doesn’t care for commercial success. Despite going viral on TikTok in 2020 for his raunchy, satirical, catchy song "Stunnin," the Nepalese Canadian-American alt-pop artist was unhappy with his career trajectory.

"I made some songs that I don’t fully love, hoping they would catch the same success as 'Stunnin’," Waters told Atwood Magazine. "But doing that made me depressed, so I had to stop and remind myself why I started making music in the first place."

Water's new album, Bad Son, was released on March 27. His press release says it is "a true immigrant story, a reflection on a young, brown creative being thrown into the mainstream overnight while navigating deep issues of self-doubt and cultural identity along the way."

Waters didn’t intend to share his immigrant story but struck inspiration as a way to cope emotionally and be honest with himself. Filled with high-energy beats, elements of indie rock, and experimental hip-hop, Waters reveals an ardent part of himself through his breathy vocals and introspective tracks.

Emily Vu

Vietnamese American pop singer Emily Vu has accomplished much in her 22 years: She amassed over 1.2 million followers on TikTok, her song "Changes" was featured in the 2023 Netflix film A Tourist’s Guide to Love, and is part of the Mastercard Artist Accelerator program. Her catchy pop tunes, including the recently released single "Heartsick," are inspired by personal moments in her life.

Vu has always been open and sure about her identity as a queer Asian woman. She came out in her 2020 music video for "Just Wait," which featured numerous women symbolizing her previous relationships. "The music video reflects how my past relationships are still burdens to me and how I still carry those experiences with me wherever I am," Vu told Stanford Daily, "I see myself being really happy with my life in a few years. I want to be happy with all that I’ve been doing and all the people I’m around."

Four years later, Vu still releases music and captivating fans on TikTok with her earthy vocals and angelic covers. Vu tells her followers on TikTok, "I just want to let you all know that I’m back. I’m going to be annoying you all every single day until I get bored."

Etu

Fijian American artist Etu is ready for the new era of the island industry, which is expanding far beyond island reggae and into different genres. "We got artists who do pop, R&B, and country. We’re going to embrace the things we bring into this," the island pop singer told Island Mongul.

Inspired by artists like Ed Sheeran, John Mayer, and Fiji, etu's hypnotic and haunting vocals fuse beautifully with traditional island music. The dreamy track "Au Domoni Iko" ("I love you" in Fijian), from his 2022 EP Spring Break, lays smooth harmonies over Fijian beats. The EP itself is filled with memorable melodies, upbeat pop styles, and uplifting lyrics.

Etu has released singles for the past two years, including island renditions of Cyndi Lauper’s "True Colors" and Rihanna’s "Lift Me Up" in February. He’s set to release his debut album, SZN I,this summer.

Etu believes Pacific Islanders are on the cusp of greatness in the music industry. "This is our moment right now," he continued to Island Mogul. "We’re moving into this era, in this season, where we get to make history… Come join this part of history or they're gonna tell it for us."

Myra Molloy

Thai American singer and actress Myra Molloy was merely 13 years old when she won "Thailand's Got Talent." She continued working in Thailand on Broadway productions and landed in the Top 6 of ABC’s Rising Star. As she pursued a music degree from Berklee College of Music, she found her love for music production and songwriting.

In 2021, Molloy dropped the sweet acoustic "stay." During the pandemic, she decided to apply the skills she acquired from college to her EP, unrequited. Released in November 2023, the album blends Molloy's soulful vocals with organic and electronic dance beats. It also marks her producing debut.

"The hardest part for me was overcoming this impostor syndrome that I couldn’t be a producer (who was taken seriously, haha)," Molloy told Melodic Magazine. "Or that I wasn’t good enough to put out music I self-produced. I always give myself a hard time. But I feel like once I got into this "flow state," things just kind of came to me very quickly and naturally, and I would come out of a producing trance. Top ten best feelings."

As an AAPI advocate, Molloy has long called for more inclusion in television, film, and music. "I just want to see more. We are coming along slowly, but I want that to be faster. It should be more. I just want to see people taking more initiative."

Shreea Kaul

R&B singer Shreea Kaul embraces her Indian heritage by fusing her silky falsetto and soulful pitch with South Asian and Bollywood sounds. Her "Tere Bina" and its accompanying music video are heavily influenced by her cultural upbringing.

Kaul wanted to be a crossover artist for Western and Indian audiences but found the lack of foundation for South Asian music challenging.

"There's so much power in community, especially in the South Asian community. We stick together. We support one another. The talent is undeniable. It's only a matter of time before people are going to catch on," she said on the "DOST" podcast. "What a lot of platforms are doing right now by bringing South Asian talent to the map is exactly what we need. So I've been trying to get myself into these spaces or just be around the community more because that's what it's going to take."

On her 2021 single "Ladke" (Hindi for "boys"), Kaul contacted fellow South Asian singer REHMA to collaborate on the song. The harmonious R&B track smoothly fuses Western elements with South Asian languages. Kaul received an overwhelmingly positive response for the song, which motivated her to keep going.

"There’s a spot in the market for artists like myself—for South Asian artists, in general," says Kaul. "Whatever degree of South Asian you want to be and incorporate into your music, there’s space for it."

ZHU

Chinese American experimental EDM music producer ZHU recorded his fourth studio album inside the historic Grace Cathedral. Released in March and fittingly titled Grace, it blends trap, gospel, dance, rock, and pop with synths, organs, and strings to create a sinister, sensual tone that perfectly complements his signature sultry vocals.

Grace pays homage to the legacy of the Bay Area and its impact on his life. "The recording of this project, as well as the whole purpose and design and visuals, has a lot of tribute to [San Francisco] thematically. I think a lot of people don’t even know that I grew up there," ZHU told EDM Identity.

At the end of the recording, ZHU and his team donned black cloaks and held a concert in the cathedral, sharing the new album with thousands of lucky fans who could attend. Like the symbolism of the cathedral, ZHU’s album represented the themes of religion and his connection to home.

"I’ve never really shared a part of the city, but I think it’s time to pay some tribute to some of the great influences that have come through the area," says ZHU.

Leap Into AAPI Month 2024 With A Playlist Featuring Laufey, Diljit Dosanjh, & Peggy Gou