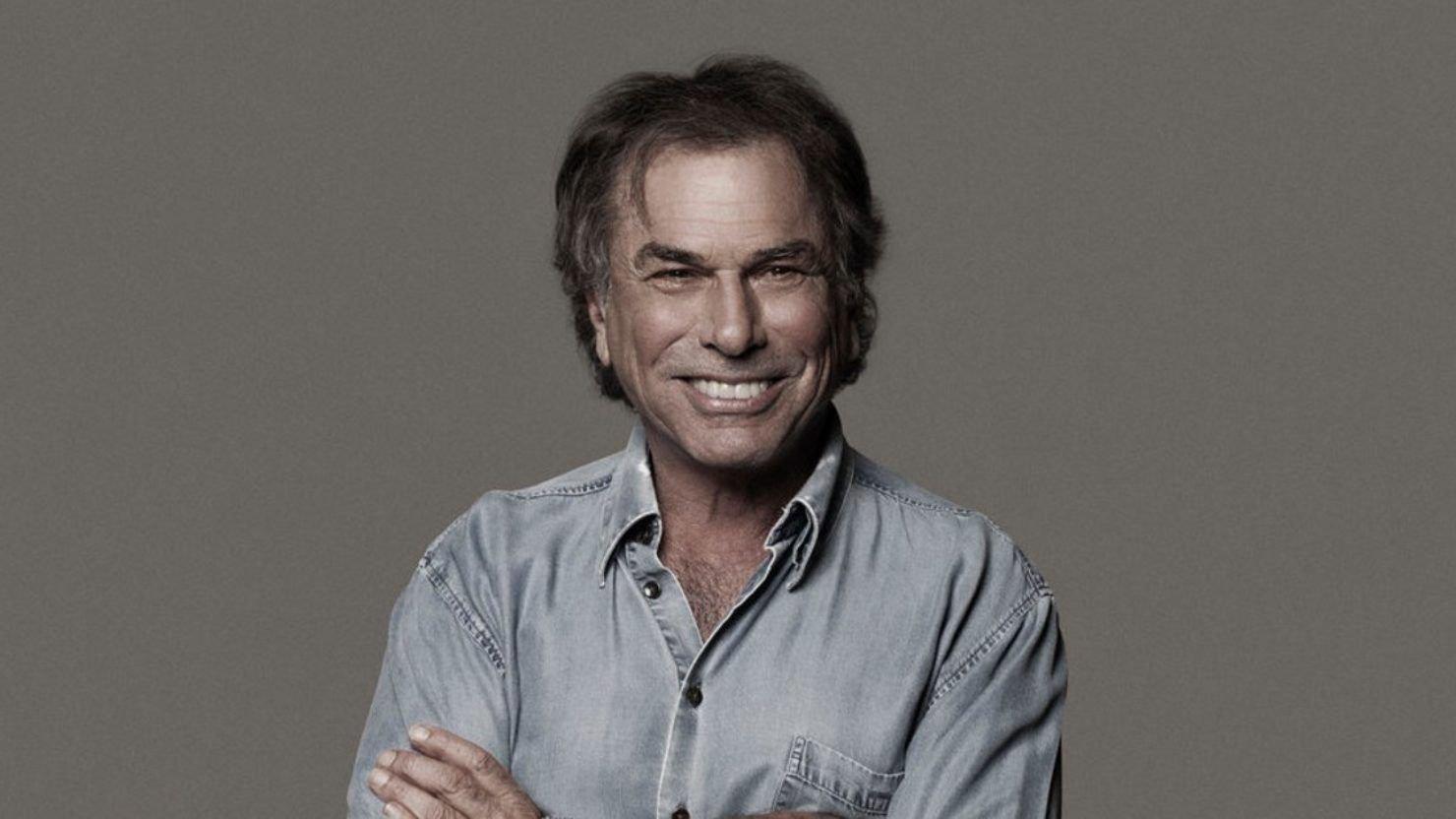

Photo: Nick Spanos

interview

Living Legends: How Dead & Company Drummer Mickey Hart Makes Visual Art From Vibrations — And Brought It To Las Vegas' Sphere

Dead & Company are currently embarking a residency at Las Vegas' sphere, which features drummer Mickey Hart's eye-popping, unconventional art. Hart spoke to GRAMMY.com about how it came to be, and how the Grateful Dead's legacy continues to ripple forth.

Living Legends is a series that spotlights icons in music who are still going strong today. This week, we interviewed Mickey Hart, one of two drummers — along with Bill Kreutzmann — of the Grateful Dead and its contemporary offshoot, Dead & Company.

His first-ever solo art exhibition, Art at the Edge of Magic, will run through July 13 at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas, as part of the Dead Forever Experience. His work is also incorporated into their current residency at Las Vegas' Sphere.

After decades behind a drum kit with the Grateful Dead, and now in the same role in Dead & Company, Mickey Hart has learned a truly cosmic lesson: "The basis of all of creation is vibratory."

For years, in parallel with his legacy as a music maker, he's made visual art using a sui generis method, which has plenty in common with his techniques as a drummer. Check out his visual art, which he's been creating for years in parallel with his music making; some of it may look like paintings, but that doesn't quite describe what it is.

Rather, Hart employs vibrations — much like he's done behind the kit for decades — to bring out hitherto-invisible dimensions in paint. The results are captivating to the eye — at times, otherworldly.

The strength of Hart's visual art has added another layer to the Grateful Dead cosmos. If you're in or near Las Vegas, you can check out these works as part of the Dead Forever Experience, in an exhibition at the Venetian running until mid-July.

Additionally, if you catch Dead & Company during their Sphere residency (which runs through July 13), you can immerse yourself in it during the famous "Drums/Space" portion of the set — a percussive, celestial section stretching way back in Dead setlist history.

"I just love to do it. Sometimes, your hobbies overtake you and become a necessary ingredient in your life," Hart cheerily tells GRAMMY.com. "And that's what happened with this visual medium, that it kind of grew on me and made me want to go back over and over and over again to learn the craft."

Whether or not you'll be heading to Vegas, read on for an interview with Hart about how he makes these sumptuous textures and hues truly pop — as well as his gratitude for the potency and longevity of the Dead's afterlife. (No pun intended.)

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Your visual work is beautiful. What can you tell readers about how you make it — the brass tacks?

Well, I wouldn't say I paint. I don't use brushes — sometimes, once in a while — but really it's more of a pouring medium, and a spinning medium, and so forth. But I use vibrations in the painting process, and I think that's why people call it vibrational expressionism.

I use a subwoofer and the Pythagorean monochord — a stringed instrument — drives the subwoofer. Pythagoras, of course, invented it, and it goes down very low to 15 cycles, sometimes 10 cycles. And that vibrates the paint. I mix multiple colors, and the colors come up within each other, and it reveals these details that you cannot get in any other way.

And I just kind of fell on it. In the beginning, I was drumming them — beating underneath them and so forth. But now, I've progressed to using a Meyer subwoofer, and it works just fine. And that's how the paintings are born. They're vibrated into existence.

Once I apply my mumbo jumbo to it, and using additives that create unique features — shapes, people, animals, mountain ranges, glaciers — you see all kinds of things within the paintings if you look at them, and let yourself go, and become part of the paintings.

Everybody has their own interpretation of [what they reveal], which is really important. These are not, like, a rose, or a vase, or a car. It's not that kind of art form. So, it raises your consciousness. And if you can connect with it, you get high. And that's what these things are all about. That's what art's all about. No matter what it is, audio or visual, it's consciousness raising at its best.

I take it you've been developing this ability in parallel with your work in the Dead universe for some time.

Well, of course. I work with vibrations. The vibratory world is where I live, and I make my art there. It's always been like that. I'm a lover of low end; low frequencies are my specialty. And because I'm a percussionist and many of my drums are very large and they speak to the range, the frequency, which is not normally accessed.

So, I create these works using these low-frequency creations. And that was something that I fell on years ago, but as a hobby; this was nothing more than an escape to another virtual headspace. Now, I share it with others.

I feel like this sound-based approach to visual art is a fairly unexplored space.

For sure. I mean, you can look it up. I've looked it up. And when you look up vibrational expressionism, I'm the only one that's there. Someone coined that term years ago, and it's kind of fitting.

I might be unique in that particular way, but that's the only way I know how to bring the colors up within themselves and reveal the super details.

Photo: Emily Frost

And I'm sure this process is fluid and mutable; you don't apply the same technique for every piece.

Yes, I apply different frequencies and different rhythms to different paintings. They're not the same. Every time I approach it — whether it be a canvas, or wood, or plexiglass, or glass, or whatever the surface is — it's always different. I never repeat. Every one of them is unique.

It's about the mixing of the paints, and the ingredients I put in the paint. And then you have to let it go and you jam. That's what these works are — they're jams. Sometimes, I have a thought on how I want it to be, and then sometimes it'll completely change once I put paint to canvas.

You learn over years. I've been doing this for about 25 years as a hobby, so I've got hundreds of these. And some of them never see the light of day. That's the luck of the draw, but luck favors the prepared mind, and I prepare that before I go in. I focus and concentrate on not concentrating. I just try to be there now and let the flow happen.

I improvise. That's my love. That's the only thing I really know how to do. Memorizing things and repeating is not who I am. I don't paint by the numbers. You don't need me for that.

Much like what you do on stage!

The Grateful Dead never did memorize many things. It was mostly a seat-of-the-pants kind of art form, but you learn how to become a seat-of-the-pants artist, if you will. There's adventure, there's failure, there's success, there's luck, there's chaos, there's order, and back and forth.

The duality of all of that reflects life. It gets you high too. You can look at it and all of a sudden you're in a different, virtual space. That's what art does — good art, anyway. It puts you in a place of great wonder and awe.

Photo: Emily Frost

Can you talk about using the Sphere as a canvas for your work?

That's how I look at it — as a blank canvas. When I hit the stage, I'm not thinking of anything. I prepared, I have my skill, I'm ready to go, but I'm not really thinking in the normal sense of the word. I throw that away and I just feel muscle memory, you might call it.

When you're playing music in a band, you become a groupist. You learn to be able to interrelate between six people each having their own consciousness, making something larger than the parts. Music is great at that. But in painting, it's a singular thing.

Music is just the moving of air. That's the delivery system. It's the movement of air. And in this case, it's light. It's what the light does to you. The eye is more powerful than the ear as an organ. So people really react to the visual. Hopefully in the Sphere, there's a combination of both that come together and form something much larger.

I appreciate that you view a drum as far more than simply a drum.

It's not something that just played to keep time. It's something that is an integral part of the orchestra, right up there with melody and harmony. The primacy of rhythm is something that has come into music in this century. If you listen to the radio, it's rhythmic-driven, mostly. Of course, there's the melodies, but the basis of it all is rhythmic.

Visual art is the same thing. It's all about rhythm and flow. If you don't have that, you don't really have anything. You have to have a groove.

The basis of all of creation is vibratory. These arts are just miniatures of what's happening in the cosmos. I mean, we are in the wash of these vibrations that were created 13.8 billion years ago from the singularity, the big bang, and that's still washing over us. And that's where art comes in. It connects you to the infinite universe at its best.

You guys seemed to realize early on that you could transcend simply playing rock songs in a band.

When we were younger, we were all ingesting psychoactive drugs. They certainly freed our perspective, and created a different kind of perspective when we all played together. Some of it was drug-related, you might say. We took what we could from those experiences and created a new kind of music.

That was an important part of our exploratory nature as we were falling on Grateful Dead music. We were exploring realms of consciousness that were not accessible to us normally in a normal waking state. These chemicals certainly helped in that respect, used correctly and professionally. They were an enormous, enormous help.

And now we're finding out that LSD is being used in therapeutic and medicinal and diagnostics and all of that. These are very helpful in many ways.

Photo: Emily Frost

How has it felt watching the Grateful Dead turn into a franchise, a universe? This visual element at the Sphere adds a whole new layer to it.

Well, it's very interesting to see all the corners and of the universe that the Grateful Dead spirit has reached and all the people and all the bands that copy our music. It's very rewarding and complimentary, I think.

We knew it was special. First time I ever heard it, I knew it was special. How special? You never know, but you have to keep at it being special. And eventually, it skips generations, which is what we've done — generation, after generation, after generation. The parents share with their kids, their kids, their kids.

It's something that's very friendly — hanging out with your parents at a concert like that, and having a great time together, and sharing something that they shared when they were younger.

It's fantastic. It's unbelievable that it has that power. I was just talking to someone the other night and they asked me to explain it. You can't explain it in words. You have to hear it. You have to be there. You have to feel it. You have to feel the community that it spawns, and this feeling that you get in the music. It's very seductive, if you allow yourself that moment.

I was just reading this morning that Diplo — the electronic musician, a very good musician — just became a Deadhead the other night.

Really!

Oh, yeah. It transformed him completely. You never can tell who gets touched by our music. It's something that's not explainable, but it keeps going on. The people will not let it go.

As long as people are interested in our kind of music and our kind of scene, we'll keep playing. There's no end to it until we don't have the facility to play, or the rhythm stops. I plan to do this till the day I die. There's no question about it. I've always thought that. There's no secret.

I think Bob and I both agree on that, and all of the Grateful Dead, Bill, Phil, certainly Jerry, we're all in the same boat when it comes to Grateful Dead music, the passion that we bring to it. And it's very rewarding that people enjoy it as deeply as they do.

I tell you, I can't express the gratitude that I have just being part of it. We all feel that same way. It's very humbling, to be honest with you, that it's grown to be this. It was just a little cub. Now it's a roaring lion. It's just a gigantic monster that is always meant for the good, and that's very rewarding. It's a good life to lead. We work very hard at it.

A Beginner's Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Jim Lauderdale

Photo: Scott Simontacchi

news

Songwriter's Songwriter Jim Lauderdale On New Album 'Hope,' Missing Robert Hunter & Why There's No Shortage Of Great Music Today

Two-time GRAMMY winner Jim Lauderdale may not be a household name, but his songs have been recorded by everyone from George Strait to Blake Shelton to the Chicks. His heartening new album, 'Hope,' contains one of his last collaborations with Robert Hunter

Even if you never get to Jim Lauderdale's thirty-somethingth album, he hopes you at least look at the cover. It's a serene, gently surreal painting by Maureen Hunter, the widow of Grateful Dead co-lyricist Robert Hunter. To him, even if record shoppers merely see that—with the word "Hope" in block letters above that—at least he'll have made a momentary impression on their hearts.

"We all need that, no matter who we are and what's going on," the songwriter's songwriter, who has won two GRAMMYs and had songs recorded by Elvis Costello, Patty Loveless, Gary Allan and others, tells GRAMMY.com. "This is as bleak as things have been for many of us in life. Some of us have seen worse, and much harder and more terrible times, but for a lot of us, this period has been pretty bad."

For his part, Lauderdale has been hanging in there, practicing tai chi, eating medicinal mushrooms to stay strong, and writing more than he ever has. This state of mind is refracted throughout Hope, which was released July 30 via Yep Roc Records. Its tunes, like "The Opportunity to Help Somebody Through It," "Breathe Real Slow" and "Joyful Noise," go beyond chord progressions and lyrics: They have legitimate therapeutic value.

'Hope' album art. Painting by Maureen Hunter.

And he had one of the most spine-tinglingly primeval lyricists on the case: the Grateful Dead's co-lyricist Robert Hunter, who wrote the words to classics like "Dark Star," "Ripple" and "China Cat Sunflower" before dying in 2019 at 78. He wrote more than a hundred songs with Lauderdale over the years; "Memory," included here," was one of the last.

"I really miss him very much and feel his presence every day and think about him every day," Lauderdale says of his old friend and collaborator. "I think he was the most interesting and intelligent guy I ever met." Read on for more expressions about Hunter, Hope and how Lauderdale keeps his bearings in an era of relentless disasters.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hey, Jim.

Hi! This is Jim Lauderdale. I'm sorry I can't get to your call right now, but please leave your name and number. It's really important to me, everybody. Each and every one of you. I promise I'll get back to you soon. Thanks. Beep! Your mailbox is full and cannot take messages at this time. [Breaks into giggles.]

Nah, I'm kidding. I love to do that to unsuspecting people.

Wow. I'm hundreds of interviews deep, but that's a first. What records are you checking out lately?

You know, there's a group from Louisiana called Feufollet. Really cool zydeco, country, rock—really diverse. My friend C.C. Adcock, who lives in Lafayette, just produced an album by a fellow, a staple down there called Tommy McLain. That's coming out in England, and I believe that Nick Lowe co-wrote a few things with Tommy, and Elvis Costello. They really love him. He's A1. I was really taken with that record.

I was also listening to some Donna the Buffalo stuff. Some Grateful Dead. Listening to some of their catalog always feels good. And a bluegrass group called High Fidelity that's got a new album. They're really, really terrific. You know, there's some good stuff out there.

That's encouraging to hear. Some people of a certain generation say, "There's been no good music since 1971."

Oh no, no. Gosh. There's plenty of stuff. Working on this radio show with Buddy Miller, the Buddy & Jim Show—outlaw country—Buddy keeps me on my toes. We need to make playlists occasionally, so I need to bring him things. Then, I'm discovering new things through him. He has a real encyclopedic musical mind. So, that's always good.

Back in the day—we're on hiatus now—but there was this show that I was working with called Music City Roots in Nashville. Usually, we had four different bands per night. We did that once a week. It's on some PBS TV station and it's a syndicated radio show, too. It's been great to hear new stuff—new artists, or even veteran artists that have new material.

There is no shortage of great music out there, new stuff. Constantly.

And the old guard is still great. People were calling Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones old guys when I was a kid, but they remain potent forces today.

That's so good. I feel like over the last few years, too, I feel like I'm writing more than I ever have, really. At first, during this pandemic, I didn't want to do everything. That did slow me down for several months, but then I started writing again.

Read More: GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Bob Dylan Accept His GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award In 1991

What was the catalyst for that?

Well, it was such a depression and this uncertainty of tragedy going on all the time. I think it was when I started thinking in terms of grabbing some songs that didn't seem to fit on a country record I was working on. I was kind of recording whatever came out. Some of these songs weren't country. Then, I wanted to get something out there to help soothe people.

So, that kind of got me back on track writing again, because I realized I had some stuff that really spoke to the time we were going through—some of these non-country songs. Some new things just started coming out then. You know, it's interesting. I feel like a lot of times, I need the structure of a concept—of some kind of album—to get me going. Because that's one of my favorite things to do—to make records.

At the same time, sometimes it can be really daunting because I'll have very little or no material prepared when I go into the studio. As the studio date gets closer and closer, something comes out, either the day before or that morning. It's not always like that, and especially if I co-write with somebody, then that can be more random.

But that helped me start writing again: When I said, "Hey, I want to get something out there to people."

Tell me about your relationship with Robert Hunter. When I think of him, I think of how strong Grateful Dead tunes are at their core, partly thanks to him.

When I first started listening to the Grateful Dead, American Beauty and Workingman's Dead were my entry port for them. I was a junior in high school in North Carolina. There was this thread, musically—because I'd been loving country and rock and bluegrass—and they were so different-sounding, but synthesizing all these different styles in a way I hadn't heard.

And lyrically—of course Dylan had done some amazing things, and had his way—but it was just so different. I felt like Robert Hunter was touching on something that was in the back of my consciousness and subconsciousness. There was something in his descriptions of things I was thinking or feeling but couldn't put into words myself. Just kind of evoking different things I felt.

Some of the lyrics were about death and things like this, that you would hear in older bluegrass songs or folk music or whatnot. But you weren't hearing about those in a rock band. That marriage of Robert's lyrics and Jerry Garcia's [music] and other members of the band he co-wrote with, there was this perfection about it to me.

Let's talk about Hope, which exudes a sense of help, gentility and care. The worst thing about this era, to me, is how we treat each other.

It's funny: When you go to a movie, depending on the type of movie, when you get up out of your seat and you're walking up the aisle, whether you're watching some superhero [movie] or you walk away feeling scared or sad or whatnot—you either feel like you want to have an altered state of consciousness after you hear a song, or you want to party, or you feel angry. All these various things.

I think things have been so horrible that I figured it can't hurt to just have some good songs that make you want to get through. You want to get through these times and you want to help other people get through these times. There's some release, some kind of relief, a little bit, because we all need that.

Not that this record is some kind of a cure-all or anything like that, but I enjoy hearing something that makes me feel good, and I hope that's what this record will do.

Well, you don't even need to qualify it as not being a cure-all. It's a personal expression and artistic offering, not a product.

Yeah, absolutely. It's not an answer or anything like that.

The reason I decided to call it Hope: There's a song on there called "Here's to Hoping." [Perhaps] even if people don't listen to the record—even if they just see this beautiful painting that Robert Hunter's wife, Maureen, did as the cover, and see the word "Hope"—that it will trigger something and release some hope. We all need that, no matter who we are and what's going on.

This is as bleak as things have been for many of us in life. Some of us have seen worse, and much harder and more terrible times, but for a lot of us, this period has been pretty bad.

Jim Lauderdale. Photo: Scott Simontacchi

One of the worst parts is this sense of fetishizing the worst possible outcome. Optimism feels like a rebellion these days.

Definitely. It brought out the worst and the best of each one of us, in some way or another, during whatever time you were in—whatever phase of this you were going through. There were many phases for a lot of us. Reading about certain people who survived certain situations that were so dire, what many of the survivors said was, "How I got through was with hope. I didn't give up hope."

Sometimes, that really does seem impossible. Hope almost seems laughable, but we just have to have it. To keep going.

What else can you tell me about the essence of the record?

Let me see. Let me grab it here. [Pauses.] Well, these songs just really seem to fit together with this theme. I co-produced it with Jay Weaver, who's the bass player. He didn't do the last bluegrass album I did, but there were two other studio albums on Yep Roc that he co-produced with me.

We used this kind of crew of guys [that typically work together], with the exception of one or two guys. I just really feel like all these musicians played so great. It's just such a joy to work with them. So, it's nice to have that camaraderie. It's like a band. That was really uplifting for me to do all this stuff with these guys.

To wrap up the thing about Robert Hunter: We started working together, I believe it was in 1996, when I was going to do my first record with Ralph Stanley. That's how it started, and then he came to Nashville for a little while. We just hit it off, writing-wise. I'd go out there sometimes to California. Sometimes, I'd send him melodies or he'd send me lyrics.

I had recorded about six albums of just our collaborations, and then there were various tracks on other solo albums of mine. So, we recorded about 88 things that we wrote. We've written about 100 songs, and some of these haven't been released.

"Memory" was the last thing he heard that we wrote, and so I'm really glad he got to hear it. I really miss him very much and feel his presence every day and think about him every day. He's a big part of my musical life, and he was a wonderful guy. I think he was the most interesting and intelligent guy I ever met.

Michael Brun

Photo: Leo Volcy

news

Why The GRAMMY Awards Best Global Music Album Category Name Change Matters

"Global Music is the future of music…The fusion of sounds breeds innovation, and global music artists are at the forefront of that movement," Haitian DJ/producer Michael Brun told us

Last week, the GRAMMY Awards were in the news because of an exciting, timely update to one of its 84 categories: Moving forward, Best World Music Album will now be known as the more inclusive Best Global Music Album. While the change might appear subtle to those not familiar with the baggage the term "world music" carries, it represents an important honoring of its past and movement towards a more inclusive, adaptive future.

The new name was decided after extensive conversations with artists, ethnomusicologists and linguists from around the world, who decided it was time to rename it with "a more relevant, modern, and inclusive term," an email sent to Recording Academy members explained.

"The change symbolizes a departure from the connotations of colonialism, folk and 'non-American' that the former term embodied while adapting to current listening trends and cultural evolution among the diverse communities it may represent."

Read on to hear from three international artists about what the new Best Global Music Album name means to them, and why it's more inclusive than "world music."

Read: The 63rd GRAMMYs: Looking Ahead To The 2021 GRAMMY Awards

"Miriam Makeba used to tell me the expression 'World Music' was a politically correct way of calling our music 'Third World Music,' therefore putting us in a closed box from which it was very difficult to emerge. Now the new name of the category opens the box wide open and allows every dream!" GRAMMY-winning Beninese singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo told us. The legendary artist won (what was then called) Best World Music Album at the 2020 GRAMMYs for her Celia Cruz tribute album, Celia, and at the 2016 and 2015 GRAMMYs.

Nigerian singer Bankulli, who is featured on Beyoncé's The Lion King: The Gift album, added, "Global Music provides a more inclusive awards platform to artists from relevant new genres. The term is encompassing of what is happening today and looks to the future for better representation."

"American ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown coined the term in the early 1960s, but it was later popularized in the 1980s as a marketing category in the media and the music industry intending to encompass different styles of music from outside of the Western world. It is by and large a determination of any type of genre or sound that Westerners consider ethnic, indigenous, folk, or simply non-American music," Uproxx explained earlier this year.

As the Guardian recently noted, "the term 'world music' was originally coined [in the music business] in the U.K. in 1987 to help market music from non-western artists… Our world music album of the month column was, like the GRAMMYs, renamed global album of the month.

Guardian music critic Ammar Kalia reasoned that the change 'does not answer the valid complaints of the artists and record label founders who have been plagued by catch-all terms. Yet, in the glorious tyranny of endless internet-fueled musical choice, marginalized music still needs championing and signposting in the west.'"

The Recording Academy awarded the first Best World Music Album golden gramophone at the 1992 GRAMMYs to Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart for his album Planet Drum. A diverse group of artists, representing many countries and musical styles, including Brazilian bossa nova great Sergio Mendes, Panamanian salsa singer Rubén Blades and South African choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo have also won over the years.

"Culturally speaking, we are living in a borderless world. Changing our language to better describe and categorize influential music from around the globe allows us to hit a reset button on how we view each other. It allows us to have a better conversation about who we are and where we're headed," Marlon Fuentes, Genre Manager, Global Music, New Age and Contemporary Instrumental at the Recording Academy, shared.

"In my opinion, this moment was symbolic of a new era that connects the past to the future. A signal that we are living in a time where creative people from all over the world are using social media and innovative approaches to overcome clichés and stereotypes by defining their identity on their own terms."

"Global Music is the future of music. As the world continues to become more interconnected, music culture no longer has borders," Haitian DJ/producer Michael Brun said. "The fusion of sounds breeds innovation, and global music artists are at the forefront of that movement. I'm happy to see the Recording Academy working to adapt to the changing landscape and celebrate excellence from around the globe."

This summer, the Recording Academy announced updates to the names and rules for four other categories, which included renaming Best Urban Contemporary Album to Best Progressive R&B Album. Conversations around nixing the term "urban music," an umbrella category encompassing traditionally Black genres like R&B and rap, came to the forefront in 2020 following the deep reckoning with racism in American and beyond. Major labels, including Universal Music Group, including affiliates Warner Music Group and Republic Records, have dropped the term.

As Billboard notes, the Best Global Music Album rename follows a similar change implemented at the 2020 Academy Awards—Best Foreign Language Film was updated to Best International Feature Film. South Korean director Bong Joon-ho won for his widely celebrated 2019 film Parasite.

The 2021 GRAMMY nominees for Best Global Music Album—along with the other 83 categories—will be announced on Nov. 24. The 2021 GRAMMY Awards and Premiere Ceremony will take place on Jan. 31, 2021, when all the big winners will be revealed.

Get To Know The 2020 Latin GRAMMYs Album Of The Year Nominees | 2020 Latin GRAMMY Awards

John Mayer and Bob Weir of Dead & Company perform in 2017

Photo: Steve Jennings/WireImage

news

Dead & Company Announce Summer 2020 U.S. Tour

The Grateful Dead offshoot, led by former guitarist Bob Weir and John Mayer, will launch the 17-date trek this July

Dead & Company, the Grateful Dead offshoot led by founding member and former guitarist Bob Weir and seven-time GRAMMY winner John Mayer, have announced a U.S. tour set for this summer. The 17-date trek, which kicks July 10 in Boulder, Colo., and ends Aug. 8 in Boston, Mass., will take the iconic psychedelic rock band to major stadiums and amphitheaters across the nation.

Ahead of the summer 2020 tour, Dead & Company will headline the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival this May. The upcoming trek follows the band's busy 2019, which saw the group touring the U.S. last summer

Read: The Rolling Stones Announce 2020 North American "No Filter" Tour Dates

Originally formed in 2015, Dead & Company is composed of former Grateful Dead members Weir, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, along with Mayer. The group also features Allman Brothers Band bassist and The Aquarium Rescue Unit founding member Oteil Burbridge as well as renowned keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, who's worked with various Grateful Dead spin-off groups, including Weir's RatDog.

Read: Guns N' Roses Announce North American Tour Dates

Tickets for Dead & Company's summer 2020 U.S. tour go on sale Friday, Feb. 14, at 10 a.m. local time. For more information and for the full tour routing, visit the band's official website.

The Spirit Of The Grateful Dead Lives On At Terrapin Crossroads

Santana at Woodstock

Photo: Tucker Ransom/Getty Images

news

New Woodstock 50th Anniversary Box Set Offers A Complete Listen To The Summer '69 Fest

The limited-edition set will allow music fans to listen to the powerful live performances from Santana, Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead and every other artist who played Woodstock '69

An official 50th Woodstock anniversary concert may or may still not be in the works, but one thing's for sure: a lot of music fans really want to celebrate the Summer of '69 on its 50th birthday.

Now, with an expansive special-edition box set titled Woodstock 50 — Back to the Garden — The Definitive 50th Anniversary Archive, listeners can hear full performances from the original Woodstock concert.

<iframe width="620" height="349" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/b2FpYymgB9s" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Spanning 38 CDs, the limited-edition (of 1,969 copies, of course) set, which will be released on Aug. 2 via Rhino, will include 432 songs, 267 of which are previously unreleased, from the three-day event. It will be the most comprehensive look at Woodstock '69, i.e., the first time every artist, including greats Santana, Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead, are included on record.

Rock On: Jimi Hendrix's 'Electric Ladyland' Turns 50

As reported by Rolling Stone, the tracks are ordered chronologically based on the actual lineup order and sets performed during that mystical weekend of Aug. 15–17, 1969, with each artist's set on one disc.

The collection came together from the work of Los Angeles producer and archivist Andy Zax and co-producer Steve Woolard, who had the herculean task of making a pile of 8-track tapes from 1969 see the light of day in the digital age of music. Zax was originally sent to take a look at the tapes back in 2005, and realized there was a massive musical treasure that needed to be unearthed. He didn't have the resources to do a fully comprehensive release with the 2009 40th anniversary Woodstock set he also worked on, so the new set will finally give (almost) all of the tracks the light of day.

"The Woodstock tapes give us a singular opportunity for a kind of sonic time travel, and my intention is to transport people back to 1969. There aren't many other concerts you could make this argument about," Zax said to Rolling Stone. "From the moment I saw those tapes, I was like, 'Oh my God, there's so much more than I'd ever thought. It was clear to me that no one was exploring this stuff and dealing with it in totality. Here was this vast trove of material not treated correctly."

The three tracks that didn't make the cut include two songs from Hendrix's set, per the request of his estate, for "aesthetic reasons." The only other missing song is from Sha Na Na.

The first 37 CDs take you through each act's show, and the 38th "bonus" CD features audio extras, like attendee anecdotes recorded during the fest.

The non-musical audio moments, also featuring off-kilter announcements, are hidden gems of the archival work themselves. Zak speaks to the 38th disc, which includes "this one guy moaning about what a disappointing experience [Woodstock] was and that it was a sell-out. It's a great slice of real people in the moment reacting to it, which pleases me immensely."

In addition to the CD collection, the deluxe edition of the new set also includes a DVD of the director's cut of the 1970 Woodstock film, the 2009 "Woodstock" book by Michael Lang and various replicas of Woodstock '69 paraphilia, like a copy of the original program book. This deluxe set, housed in a plywood box designed by GRAMMY-winning graphic designer Masaki Koikethe, costs $800 and is the only option with the full audio.

Rhino also offers more economic 10-CD, 3-CD or 5-LP vinyl sets; all four options are available for pre-order now.

Pieces Of Woodstock's Original Wooden Stage Are Now Collectibles