The Beatles and grief have always been fundamentally intertwined. When John Lennon and Paul McCartney met as teenagers, they bonded over losing their mothers early on. Their manager, Brian Epstein, died in 1967 at only 32; as McCartney put it during the ensuing Get Back sessions, "Daddy's gone away now, you know, and we're on our own at the holiday camp."

Lennon's murder in 1980, at just 40 years old, imbued their story with bottomless longing — not just between this band of brothers, but a world that had to process the Beatles were never coming back. George Harrison's death from cancer, in 2001, was another catastrophic blow.

But the Beatles' message, among many, was that the light prevails. And from "In My Life" to "Eleanor Rigby" to "Julia" to "Let it Be" and beyond, almost nobody made sorrow sound so beautiful. And "Now and Then," billed as "the last Beatles song" — yes, the AI-assisted one you heard about throughout 2023 — is liable to move you to the depths of your soul.

A quick AI sidebar: no, it's not the generative type. Rather, it's the technology Peter Jackson and company used to separate theretofore indivisible instruments and voices for the Get Back documentary. It also worked in spectacular fashion for Giles Martin's — son of George — 2022 remix of Revolver.

*The cassette edition of "Now and Then." Photo © Apple Corps Ltd.*

With this tech, Martin and his team were able to lift a Lennon vocal from a late-'70s piano-and-vocals demo of "Now and Then," a song he was workshopping at the time. (Remember "Free as a Bird" and "Real Love," the reconstituted Beatles songs from the Anthology era? "Now and Then" was the third one they tried — and, until now, aborted.)

The final version of "Now and Then" features Lennon's crystal-clear, isolated vocal, as well as Harrison's original vocal and rhythm guitar from that 1995 session. McCartney adds piano and guitar, including a radiant slide guitar solo in homage to Harrison. Ringo Starr holds down the groove and joins on vocals.

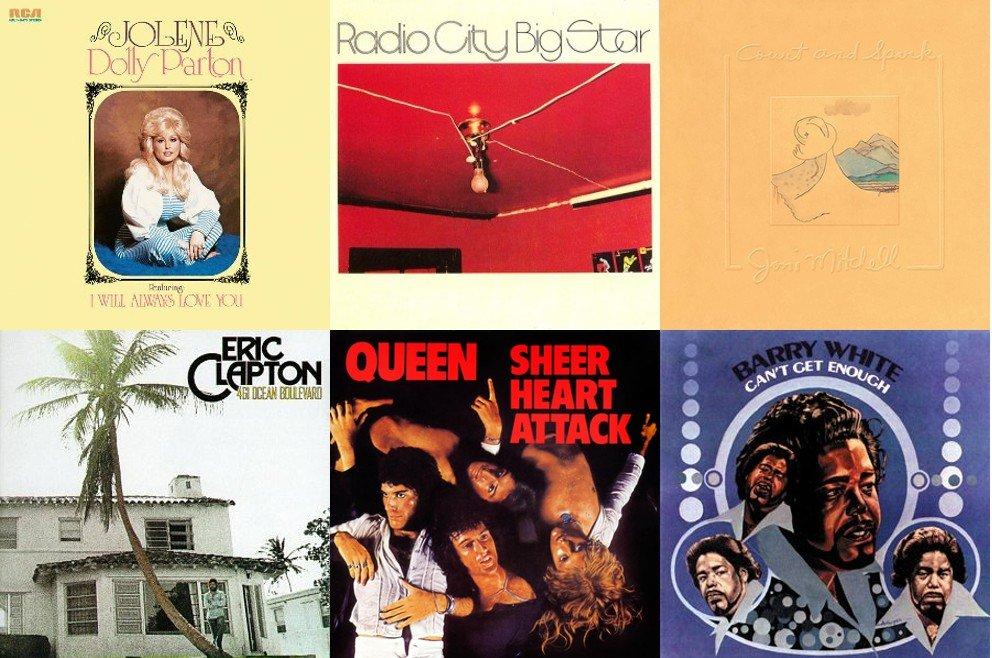

"Now and Then" is more than a worthy parting gift from the most beloved rock band of all time. And you can experience it a la carte or as part of the Red and Blue albums — the Beatles' epochal, color-coded 1973 hit compilations, remixed by Martin, with expanded tracklistings, out Nov. 10.

Ahead of "Now and Then," which will arrive on Nov. 2, read an interview with Martin about his approach to the emotionally steamrolling single — and the host of Beatles classics that flank it on Red and Blue.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What was the thinking behind the expansion of the Red and Blue albums?

That kind of stemmed from "Now and Then," really. You know, we finished "Now and Then," and then there was the thought about, OK, it can't go on an album. What are we going to put it on?

There was a thought about trying to respect people's listening tastes. And the fact that they've changed — and the No. 1s, for example, don't really reflect the most popular Beatles songs that people are listening to.

Then, we realized it was the 50th anniversary of Red and Blue. For a whole generation — much older than you, my generation — the Red and Blue albums have this sort of gravitas behind them. I know all the tracklistings; even though I think I was 3, when they came out, we had them at home.

So, we decided to do the Red and Blue albums — which took quite a long time, because there was quite a lot of stuff to do on them.

Since you've remixed all the Beatles albums from Sgt. Pepper's onward, I've been glued to the pre-1967 material — this is the first time I've heard your touch on their early work. Remixing songs as early as 1962 must have been a whole different ballgame.

In all honesty, that was the fun bit.

You know, we couldn't have worked on these songs six months ago; the technology had to be developed in place so we could do this — separate drums, bass and guitar, and have the different elements. And they sound good; it doesn't sound strange or artifact-y in any way.

I think people will talk about "Now and Then" for "Now and Then." But I [also] think the true innovations come back from the early Beatles stuff. The way that it pops out; the way that the records still sound like the same records. Hopefully, the character doesn't change, but the energy is different.

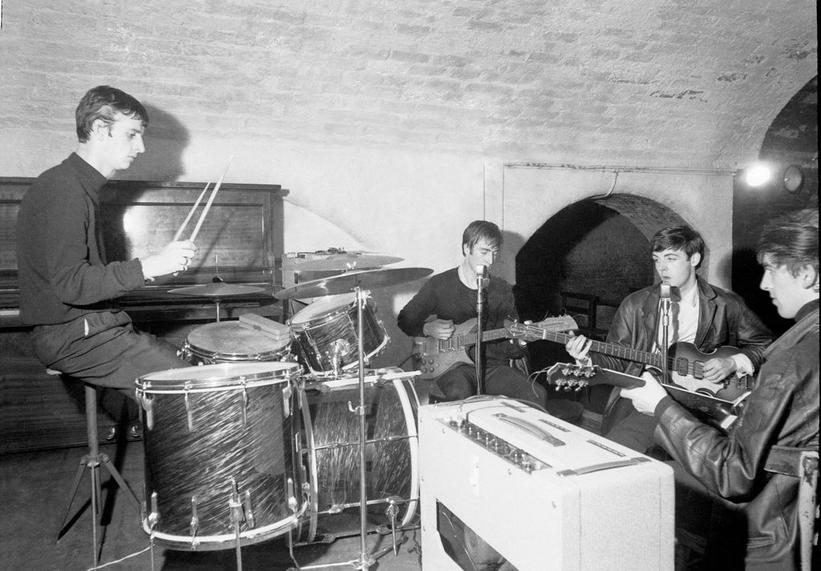

Ringo always said, "We're just a bunch of punks in the studios," and they sound like a bunch of punks in the studios. Now, they sound the age they were when they played it.

And that's so key to me, to making these records — that they sound like that. You know, they were way younger than Harry Styles is now, when they were making these records. People think they're old guys, and they're not.

That, to me, is important, in a way. We get old — I hate to break that to you, but we do get old. And recordings, by their nature, stay the same age. And the Beatles will always be that age on those records.

I think, now, they sound like a bunch of young guys in the studios bashing their instruments, and I think that's really exciting, and the technology we've applied has enabled us to, bizarrely, strip back the inadequacies of the technologies they had.

And I don't mean that in a pompous way. What I mean is that my dad never wanted the Beatles to be coming out of one speaker, and then coming out of another speaker. They didn't want the two tracks to be like that. He hated it. He hated it.

But now, we can have the drums coming out of the middle, like a record is now. He can luxuriate in that, and I think it's fun and exciting.

I'm noticing so many heretofore-obscured details in their early work. The vocal flub on "Please Please Me." The maniacal bongos that power "A Hard Day's Night."

I think you're right, but I think from experience — which, actually, I have a lot of now — there is a beauty in the reality.

What I mean by that is: so much music is perfect, and it's fabricated. There are checks and balances that go on, to make sure that everything is in tune, in time. And all this stuff goes on, which is fine and it suits a place. But it's a bit like the dangers of plastic surgery — everyone ends up looking the same.

And in records, everyone's sounding the same. We dial in so it's exciting, and it becomes boring, essentially, is what I mean.

The excitement you get from hearing a mistake in a song you've heard for years doesn't necessarily demean the song itself. It doesn't make you think, Oh my god, the band is s—. You think, Oh my god, what's exciting is these are humans. These are human beings in a room, making noise.

People go, "Well, who's responsible for the sound of the Beatles? Is it your dad? Is it Geoff Emerick? Is It Norman Smith…" blah, blah, blah. I go, "No, it's the Beatles. It's the fact they're four friends in a room. They make that noise."

And that's the thing about great bands; great bands make a great noise together, and they don't even know how they do it themselves. That's the beauty of it.

It's like, why do you love someone? "Well, because they're nice to me," or because they're whatever. You can't explain things; they just happen. And there's something about "Please Please Me," all that early stuff — you can hear it. It's something just happening, and that's so exciting. God, I sound like such an old hippie.

*The Beatles in The Cavern, Liverpool, August 1962. Photo © Apple Corps Ltd.*

Your first Beatles remix project, for Sgt. Pepper's, came out five years ago. On the other side of the coin, The Blue Album features songs from that dense, psychedelic era, like "I Am the Walrus," which is such a beast. That must have been a different kind of fun.

Yeah, well, "Walrus" is a beast. I've actually gone back and re-changed the stereo [mix] recently, because I got asked questions like, "Why did I change the end section so it didn't sound like the original?" I was thinking, Did I? I didn't do it deliberately. It's just the balance of speech versus vocals and stuff like that.

I was very lucky, because "Walrus" was on the Love album and show. I tackled a version of that before, and know how tricky it is.

Because by its nature, "Walrus" sounds technically bad, but it's beautiful. It's beautifully ugly as a record, and they're the hardest ones, because you don't want to take away the character. You don't want to remove the grime, because the grime is the record. I spent a lot of time looking at this and doing this — hopefully, we're in a good place with "Walrus."

You know, music's about, How does this make you feel? You don't want to feel secure around "Walrus" at any stage; you want to be unnerved by it. People sort of ask about plugins and technology, and it's like, it's not about that — something you can get on a shelf. How it makes you feel is the most important thing.

You once said that a White Album remix couldn't be too smooth — it's "slightly trashy. It's visceral. It slaps you in the face." I thought of that while listening to the remixed "Old Brown Shoe"; George's vocal is way grimy on that one.

This is going to sound really ridiculous — and I've been through this with a number of different people — but my job is to make a record sound like how you remember it sounding. Because records never sound like how we remember them sounding. And you go back and go, Was that really there?

Some people accuse me of doing stuff that I haven't done, or maybe forgot to do, or whatever. But the fact of the matter is that we kid ourselves all the time, and we fill in the blanks constantly.

It's like, "What about the vocal of 'Old Brown Shoe'? Why does it sound like this?" And I go, "Well, it sounds like that on the record." It's part of the character of the record. If it was too clean, it wouldn't sound [right].

George was very particular at that stage. He didn't get many goes, is the way I would say it, because he wasn't given enough songs.

There's a story [Beatles engineer] Ken Scott told about The White Album, of him doing "Savoy Truffle" — which is incredibly bright as a song, by the way. And my dad apparently went, "You know, it sounds quite bright, George." And he goes, "I know, and I like it." Like, "I know, and f— off," basically.

You have to respect the artists' wishes when you're doing these things, even though they're not there. Yeah, on "Old Brown Shoe," the vocal's quite strange. But that's what George wanted it to sound like, and [far be it from] me to say it shouldn't sound like that.

*The Beatles in 1965. Photo © Apple Corps Ltd.*

What's your understanding of the extent of the work the Beatles put into "Now and Then" back in 1995, before they aborted it?

I wasn't there, so I'm just going to speculate. What Paul played me — what we worked on together — was kind of after he'd looked at the material they did together.

Far be it from me to argue with a Beatle: there were some things that I thought we should change from that recording. There were a few synth [things], which I thought, once we decided to put strings on it, [weren't necessary].

You know, the key thing is that George is playing on it. Therefore, it is, by definition, a Beatles song, because all four of them are on it. People ask me, "Why is this the last Beatles song?" Well, there's not another song. There won't; there can't be another song where all four Beatles are playing on it.

So, there were bits and pieces that were used and not used. I don't think they spent a lot of time working on it, but essentially, what we kept was George — and obviously, John's vocal, which then we looked at.

Listening, I was thinking, Thank god that George tracked a rhythm guitar part and harmony vocal back then. Or else, this couldn't happen. Or, if it happened, you and your team would never hear the end of it.

What was interesting was, we did the string arrangement. I sat down with Paul in L.A., and there are lots of chugs and "Eleanor Rigby" kinds of ripoffs in the string arrangement.

And what essentially happened was, Paul spent a lot of time listening to what George was playing on the guitar, and it really changed the arrangement. It's in service to the guitar; it doesn't go against George's playing. They were completely respectful of the other Beatles, and made sure it was a collaboration, and it was all four of them.

As Yoko said to me, "John is just a voice now." And I think it sounds like the Beatles, "Now and Then."

Looking at the post-"Now and Then" Beatles landscape, I'm enticed by which Beatles albums you'll remix next. The select tracks on Red and Blue open a door to what Rubber Soul or Beatles For Sale redux might sound like.

Technology doesn't — and never has — made great records, but it creates a pathway. You can do certain things that you couldn't do in the past. And the most exciting thing for me is — as you say — it does open that door to that early material, which we couldn't have done before.

I suppose fortuitously, we kind of worked backwards, in a way — and it made sense to do that. I couldn't have done what I've done on The Red Album even six months ago, probably; it's that quick. I love the fact that the Beatles are still breaking new ground with technology that will pave the way for other artists.

*The Beatles during a photo session in Twickenham, 9 April 1969. Photo: Bruce McBroom / © Apple Corps Ltd.*

I can't imagine what this next week of "Now and Then" promotion will be like. There's an incredible weight to this. You must be feeling that.

Well, I mean, there's some perspective. My mom's just died. So, it's like [dark laugh] what's important in life?

It's a funny time. We just talked about her funeral arrangements, and she's getting buried the day, I think, the record comes out. So, there are personal things for me in this.

I've been doing interviews this week, and people have asked me, "How do you feel about what your motivation was?" Somebody was saying I'm talking about the Beatles as a resource, or whatever. I go, "You do these things and hope people get touched by stuff."

When you say you enjoy "Now and Then," that's really nice, because that's why we do it. We do it so people can listen to stuff and not just hear it. "Now and Then" sounds like a love song. It sounds like a song that John wrote for Paul, and the other Beatles: "I miss you/ Now and then."

It sounds like Paul has gone there, which I think he did. You know, no one told Paul to go and do it, and Paul didn't go, This would be a great exercise for the Red and Blue Album.

He was at home in the studio. He dug on the record and started working on it, because it's his mate. And he really misses John. I mean, that's the truth. They broke up, and John died nine years later. It really isn't very long.

So, I hope that people listen to the record and they think about loved ones. Or they think about things. That's what I hope. I don't really care about anything else — do you know what I mean? What I'm excited by is people being touched by it.

Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, The Beatles, Paul McCartney